0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Logan Huett thought he knew the West. Once a scout with the Army, he was familiar with both the hardships and rewards of pioneer life. But not even Logan could foresee the challenges that lay ahead for him and his young wife Lucinda - raising a brood of headstrong children, struggling to achieve financial security in the wilderness, concealing a long-buried family secret, and, finally, surviving the tragedy dealt them by a devastating war.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

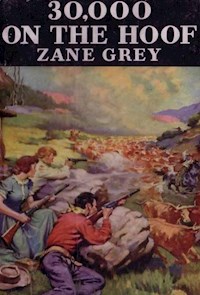

30,000 on the Hoof

by Zane Grey

First published in 1940

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Chapter One

General Crook and his regiment of the Western Division of the U.S. Army were cutting a road through the timber on the rim of the Mogollon Mesa above the Tonto Basin. They had as captives a number of Apache Indians, braves, squaws, and children, whom they were taking to be placed under guard on the reservation.

At sunset they made camp at the head of one of the canyons running away from the rim. It was a park–like oval, a little way down from the edge, rich with silver grass and watered by a crystal brook that wound under the giant pines. The noisy advent of the soldiers and their horses and pack–mules disturbed a troop of deer that trotted down the canyon to stop and look back, long ears erect.

Crook's campaign was about over and the soldiers were jubilant. They joked with the sombre–eyed Apaches, who sat huddled in a group under guard. Packs and saddles plopped to the grass, the ring of axes echoed through the forest, blue smoke curled up into sunset–flushed pines.

The general, never a stickler for customs of the service, sat with his captain and a sergeant, resting after the hard day, and waiting for supper.

"Wonder how old Geronimo is going to take this," mused Crook.

"We haven't heard the last of thet redskin," replied Willis, emphatically. "He'll break out sooner or later, and then there'll be hell to pay."

"I'm glad we didn't have to kill any of these Apaches."

"We were lucky, General. I'll bet McKinney will burn powder before he stops thet Matazel an' his braves. Bad youngsters."

"Do you know Matazel, sergeant?" inquired Crook.

"I've seen him. Strappin' young buck. Only Indian I ever saw with grey eyes. He's said to be one of Geronimo's sons."

"Wal, McKinney won't stand any monkey business from thet outfit," added Willis. "He's collared them by this time. Huett knows the country. He'll track them to some hole in the woods."

"Good scout, Logan Huett, for so young a man. He has been invaluable in this campaign. I shall recommend him to my successor."

"Huett is through with army scout service after this campaign. He'll be missed if old Geronimo breaks out an' goes on the warpath. Fine woodsman. Best rifle shot I ever saw."

"What is Huett going to do?"

"Told me he wanted to go home to Missouri for a while. He's got a girl, I reckon. But he's hipped on the West an' will soon be back."

"He surely will," added the other officer. "Logan Huett was cut out for a pioneer."

"The West needs such men more than the Army…. Hello, I hear shouts from above."

"Bet thet's McKinney now," said Willis, rising.

"Sure enough. I see horses an' army blue through the trees," added the sergeant.

Presently a squad of soldiers rode down into the glade. They had three mounted Indians with them and another on foot, a tall lithe brave, straight as an arrow, whose bearing was proud. These captives were herded with the others. Sergeant McKinney reported to General Crook that he had secured Matazel and three of his companions. The others got away on foot.

"Any shooting?" queried the general.

"Yes, sir. We couldn't surprise them an' they showed fight. We have two men wounded, not serious."

"I hope you didn't kill any Indians."

"We didn't, to our knowledge."

"Send Huett to me."

The scout approached. He was a young man about twenty–three years old, dark of face. In fact he bore somewhat of a resemblance to Matazel, and he was so stalwart and powerfully built that he did not look tall.

"What's your report, Huett?"

"General, we made sure of getting Matazel alive," replied the scout, "otherwise none of them would have escaped…. I guessed where Matazel's bunch was headed for. We cut in behind them, chased them into a box canyon, where we cornered them. They had but little ammunition, or we'd had a different story to tell."

"Don't dodge the main point, as McKinney did. Were there any Indians killed?"

"We couldn't find any dead ones."

"Willis, fetch this Apache to me."

In a few moments Matazel stood before the general, his arms crossed over his ragged buckskin shirt, his sombre eyes steady and inscrutable.

"You understand white man talk?" queried General Crook.

"No savvy," replied Matazel, sullenly.

"General, he can understand you an' speak a little English," spoke up the sergeant who knew Matazel.

"Did my soldiers kill any of your people?"

The Apache shook his head.

"But you would have killed us," said the general, severely.

Matazel made a magnificent gesture that embraced the forest and the surrounding wilderness.

"White man steal red man's land," he said, loudly. "Pen Indian up. No horse. No gun. No hunt."

General Crook had no ready answer for that retort.

"You Indians will be taken care of," he said presently. "It's better for you to stay peaceably on the reservation with plenty to eat."

"No!" thundered the Apache. "Geronimo say better fight—better die!"

"Take him away," ordered the general, his face red. "Captain Willis, according to this Apache, it sounds as if old Geronimo will break out all right. You had it figured."

Before the sergeant led Matazel away the Indian bent a piercing glance upon the scout, Logan Huett, and stretching out a lean red hand he tapped Huett on the breast.

"You no friend Apache."

"What do you want, redskin?" demanded Huett, surprised and nettled. "I could have shot you. But I didn't. I obeyed orders though I think the only good Indian is a dead one."

"You track Apache like wolf," said the Indian, bitterly. His eagle eyes burned with a superb and piercing fire. "Matazel live get even!"

It was Autumn before Logan Huett was released from his military duties, once more free to ride where he chose. Leaving the reservation with light pack behind his saddle he crossed the Cibeque and headed up out of the manzanita, scrub oak and juniper to the cedars and piñons of the Tonto Rim.

The trail climbed gradually. That same day he reached the pines and the road General Crook had cut along the ragged edge of the great basin. Huett renewed his strong interest in this mesa. From the rim, its highest point some eight thousand feet above sea level, it sloped back sixty miles to the desert. A singular feature about this cliff was that it sheered abruptly down into the black Tonto Basin on the south while the canyons that headed within a stone's throw of the crest all ran north. A few miles from their source they were deep grassy valleys with heavily timbered slopes. The ridges between the canyons bore a growth of pine and spruce, and the open parks and hollow swales had groves of aspen and thickets of maple. The region was a paradise for game. It had been the hunting grounds of the Apache, and they had burned the grass and brush every year, making the forest open.

Back toward the Cibeque several cattle combines, notably the Hashknife outfit, ran herds of doubtful numbers on the lower slopes. At Pleasant Valley sheepmen and cattlemen were at odds over the grazing. Sooner or later they would clash.

Huett left that country far behind to the east. He traveled leisurely, camping in pretty spots, and on the third night reached the canyon–head where he had brought Matazel and his Apache comrades to General Crook, which service practically ended the campaign.

He found where the soldiers had built their camp–fires, little heaps of white and lilac ashes in the grass. He thought of the sombre–eyed Matazel and remembered his threat.

At this lonely camp Huett fell back wholly into the content of his pondering dream. He had not enjoyed the military service. The range life he had led before his campaign suited him better. But he had long dreamed of being a cowboy for himself. The hard riding, the camp fare, the perilous work and adventure were much to his liking, but he had revolted against the noisy, bottle–loving, improvident louts with whom he had to ride.

He broiled turkey over the red coals of his dying aspenwood fire. With salt, a hard biscuit, and a cup of coffee he thought he fared sumptuously. In that still autumn close of day, in the whispering forest Logan Huett found himself. He might have been aware of the surpassing beauty of the glade, of the giant pines and silver spruce, of the white and gold aspen grove on the slope, of the spot of scarlet maple higher up, but he did not think of it that way. He was alone again. Slowly the pondering thought of his long–cherished plan faded into sensorial perceptions. The gusto with which he ate the hot turkey meat, the smell of the woodsmoke, the changing of the colored shadows all about him, the tinkle of the little stream, the crack of deer or elk horns on a dead branch up the canyon, the whisper in the tips of the spruce, the watching, listening sense of his loneliness,—these he felt with singularly sweet and growing vividness, but he did not think of them. He did not know that they accounted for his content. He never established any relation between them and the life of his ancestors or the primitive heritage they had left him.

He slept in his clothes, between his saddle–blankets, with his saddle for a pillow. When the fire burned down, the cold awakened him and he had to get up to replenish it. At dawn crackling white frost covered the grass. Going out to procure firewood he saw bear tracks in an open place. These had been made by a cinnamon, as he could tell by the narrow heel. A cinnamon bear was not the most welcome visitor a camper could have in those hills.

Huett made an early start and headed north down the canyon. Deer, elk, coyotes melted up the slopes at his approach. The tips of the pines high on the western ridge–crest turned gold and gradually that bright hue descended. Not until the sun was on the grass in the canyon did he see any turkeys. After that he came upon flock after flock, one in particular being composed of huge old bronze and white gobblers, with red heads and long beards, wild from age and experience.

All this continual sight of game quickened his interest and speculation in a canyon he knew and which he was going to visit. For three years this canyon had been a subject of intensive thought.

He was not certain he could reach it that day, for he had much travel up and down the ridges which lay between. When he had journeyed perhaps a score of miles down from the rim and the canyon was widening and growing shallow, he took to the slope and headed west. Travel then was slow, up through brush and across ridge, around windfalls and down into another canyon. He kept this up for hours. Most of the larger canyons had seldom–ridden trails along the brooks that traversed them.

When the giant silver spruce trees that flourished only at high altitude began to fail Huett knew he was getting down country and perhaps too far north. He swerved more to the west. Dusk found him entering one of the endless little grassy parks. He camped, and found the night appreciably warmer. Next morning he was off at dawn.

About noon, in the full light of sun, Huett came out upon the edge of the canyon that he had run across while hunting three years before and had passed twice since, once in early winter. Compared to many of the great valleys he had crossed this one was insignificant. But it had peculiar features, no doubt known only to himself, and which made it of extreme interest.

He had never ridden completely around this canyon or from end to end. This part that he had hit upon happened to be toward the south, and it was impossible to ride down into it from where he worked along the rim. He came at length to the great basin with which he was familiar. It had no outlet. The sparkling stream, shining like a ribbon, disappeared in the rocks under the south wall. Huett circumnavigated the basin, which, as far as he could determine, was the largest open pasture in the Mogollon forest. It was oblong in shape, of varying width, and miles long. All around the top ran a rim of gray or yellow limestone, an insignificant wall of rock: crumbling, of no particular height, and certainly something few men would have looked at twice.

But for Logan Huett that band of rock possessed marvelous interest. It was a natural fence. Cattle could not climb out of this canyon. Here was a range large enough to run twenty, probably thirty thousand head of stock, without the need of riders. This canyon had haunted Logan Huett. Here his passion to be a cattleman could be realized, and without any particular capital he could build up a fortune.

Huett rode around the south side and up along the west, finding a few breaks that would have to be fenced. Heavy pine forest covered this western slope. Scarcely a mile back in the woods ran the road from Flagstaff into the little hamlet of Payson, through the rough brakes of the Tonto, down to the Four Peak Range, and out to Phoenix. Settlers looking for ranges to homestead passed that point every summer, never dreaming of what Huett now saw—the most wonderful range in Arizona.

Apaches had once used this beautiful site for a hunting camp. Huett had found arrow heads there and bits of flint where some old savage had chipped his points. The brook made several turns between the gradually leveling slopes. Scattered pines trooped down to the deep blue pools. The bench on the east side had waited for ages for the homesteader to throw up his log cabin there. It was a level bit of ground, above the swift bend of the stream, and marked by a few splendid pine trees. A magnificent spring gushed from the foot of the slope. Deer and elk trails led up through a wide break in the rock wall. This opening, and a larger one at the head of the canyon were the only breaks in the upper half of the natural fence.

"I'll come back," soliloquized Huett, with finality. For so momentous a decision he showed neither passion nor romance. He had a life work set out before him. This was the place. He wasted no more time there, but rode across the flat below the bench, and climbed the west slope. At the summit he turned for one last look. His glance caught the white and bronze of the great sycamore tree shining among the pines. In honor of that tree Huett named his ranch Sycamore Canyon.

The early afternoon hour gave him hope that he could make Mormon Lake before night. The dusty road held to the levels of the dense pine forest, and Huett did not know the country well enough to try a short cut. Trotting his horse, with intervals of restful walk, he made good time.

A new factor suddenly engaged Logan's mind. He wanted a wife. The life of a lonely ranchman in the wilderness appealed strongly to him, but a capable woman would add immeasurably to his chances of success without interfering with his love of solitude. While he was employing the daylight hours with his labors and his hunting, she would be busy at household tasks and the garden.

Lucinda Baker would be his first choice. She had been sixteen years old when he left Independence, a robust blooming girl, sensible and clever, and not too pretty. She had told him that she liked him better than any of her other friends. On the strength of that Logan had written her a few times during his absence, and had been promptly answered. Not for six months or more now, however, had he heard from Lucinda. She was teaching school, according to her last letter, and helping her ailing mother with the children. It crossed Logan's mind that she might have married some one else, or might refuse him; but it never occurred to him that if she accepted him he would be dooming her to a lonely existence in the wilderness.

Thinking of Lucinda Baker reminded Logan that he had not been much in the company of women. However, she had always seemed to understand him. As he rode along through the shady silent forest, he remembered Lucinda with a warmth of pleasure.

By sunset that day Huett reached the far end of Mormon Lake, a muddy body of surface water, surrounded by stony, wooded bluffs. On the west and north sides there were extensive ranges of grass running arm–like into the forest. The Mormon settler who had given the lake its name had sold out to an Arizonian and his partner from Kansas.

"Wal, we got a good thing hyar," said the Westerner Holbert. "But what with the timber wolves an' hard winters we have tough sleddin'. You see its open range an' pretty high."

"Any neighbors?" asked Huett.

"None between hyar an' the Tonto. Jackson runs one of Babbitt's outfits down on Clear Creek. Thet heads in above Long Valley. Then there's Jeff an' Bill Warner, out on the desert. They run a lot of cattle between Clear Creek an' the Little Colorado. Toward Flagg my nearest neighbor is Dwight Collin. He has a big ranch ten miles in. An' next is Tim Mooney. Beyond St. Mary's Lake the settlers thicken up a bit."

"Any rustlers?"

"Wal, not any out an' out rustlers," replied Holbert evasively. "Rustler gangs have yet to settle in this section of Arizona."

"Wolves take toll of your calves, eh?"

"Cost me half a hundred head last winter. Did you ever hear of Killer Gray?"

"Not that I remember."

"Wal, you'd remember thet lofer, if you ever seen him. Big gray timber wolf with a black ruff. He's got a small band an' he ranges this whole country."

"Why don't you kill him?"

"Huh! He's too smart for us. Jest natural cunnin', for a young wolf."

"I like this Arizona timber land," declared Huett, frankly. "And I'm set on a ranch somewhere south of the lake."

"Wal now, thet's interestin'. What did you say yore name was?"

"Logan Huett. I rode for several cattle outfits before I worked as scout and hunter for Crook in his Apache campaign."

"I kinda reckoned you was a soldier," returned Holbert, genially. "Wal, Huett, you're as welcome out hyar as May flowers. I hope you don't locate too far south of us. It's shore lonely, an' in winter we're snowed in some seasons for weeks."

"Thanks. I'll pick me out a range down in the woods where it's not so cold…. Would you be able to sell me a few cows and heifers, and a bull?

"I shore would. An' dirt cheap, too, 'cause thet'd save me from makin' a drive to town before winter comes."

"Much obliged, Holbert. I've saved my wages. But they won't last long. I'll pick up the cattle on my way back."

"Good. An' how soon, Huett?"

"Before the snow flies."

* * * * *

All the way into Flagg next day Logan's practical mind resolved a daring query. Why not wire Lucinda to come West to marry him? He resisted this idea, repudiated it, but it returned all the stronger. Logan's mother had not long survived his father. He had a brother and sister living somewhere in Illinois. Therefore since he had no kindred ties, he did not see why it would not be politic to save the time and expense that it would take to get him to Missouri. He had already bought cattle. He was eager to buy horses, oxen, wagon, tools, guns, and hurry back to Sycamore Canyon. The more time he had in Flagg the better bargains he could find.

Flagg was a cattle and lumber town, important since the advent of the railroad some half dozen years previously. It had grown since Huett's last visit. The main block presented a solid front of saloons and gambling halls, places Logan resolved to give a wide berth. He was no longer a cowboy. Some man directed him to a livery–stable where he turned over his horse. Next he left his pack at a lodginghouse and hunted up a barber shop. It was dusk when he left there. The first restaurant he encountered was run by a Chinaman and evidently a rendezvous for cowboys, of which the town appeared full. Logan ate and listened.

After supper he strolled down to the railroad station, a rude frame structure in the center of a square facing the main street. Evidently a train was expected. The station and platform presented a lively scene with cowboys, cattlemen, railroad men, Indians and Mexicans moving about. Logan's walk became a lagging one, and ended short of the station–house. It seemed to him that there might be something amiss in telegraphing Lucinda such a blunt and hurried proposal. But he drove this thought away, besides calling upon impatience to bolster up his courage. It could do no harm. If Lucinda refused he would just have to go East after her. Logan bolted into the station and sent Lucinda a telegram asking her to come West to marry him.

When the deed was done irrevocably, Logan felt appalled. He strode up town and tried to forget his brazen audacity in the excitement of the gambling–games. He suppressed a strong inclination toward drink. Liquor had never meant much to Logan, but it was omnipresent here in this hustling, loud cow town, and he felt its influence. Finally he went back to the lodginghouse and to bed. He felt tired—something unusual for him—and his mind whirled.

The soft bed was conducive to a long restful sleep. Logan awoke late, arose leisurely, and dressed for the business of the day. Presently he recalled with a little shock just how important a day it was to be in his life. But he did not rush to the telegraph office. He ate a hearty breakfast, made the acquaintance of a droll Arizona cowboy, and then reluctantly and fearfully went to see if there was any reply to his telegram. The operator grinned at Logan and drawled as he handed out a yellow envelope: "Logan Huett. There shore is a heap of a message for you."

Logan took the envelope eagerly, as abashed as a schoolboy, and the big brown hands that could hold a rifle steady as a rock shook perceptibly as he tore it open and read the brief message. He gulped and read it again: "Yes! If you come after me—Lucinda."

An unfamiliar sensation assailed him, as he moved away to a seat. Then he felt immensely grateful to Lucinda. He read her message again. The big thing about the moment seemed the certainty that he was to have a wife—provided he went back to Missouri after her. That he would do. But it flashed across his mind that as Lucinda had accepted him upon such short blunt notice she really must care a good deal for him, and if she did she would come West to marry him. Under the impulse of the inspiration he went to the window and began a long telegram to Lucinda, warm with gratitude at her acceptance and stressing the value of time, that winter was not far away, the need of economy, the splendid opportunity he had, ending with an earnest appeal for her to come West at once. Logan did not even read the message over, but sent it rushed up town.

"I've a hunch—she'll come—and I'm dog–gone lucky," he panted.

That day he spent in making a list of the many things he would need and the few he would be able to buy. Rifles, shells, axes, blankets, food supplies and cooking utensils, a wagon and horses, or mules, he had to have. Then he hurried from his lodginghouse to make these imperative purchases. Prices were reasonable, which fact encouraged him. During the day he met and made friends with a blacksmith from Missouri named Hardy. Hardy had tried farming, and had fallen back upon his trade. He offered Logan a wagon, a yoke of oxen, some farming tools, and miscellaneous hardware for what Huett thought was a sacrifice. That bargain ended a day that had passed along swiftly.

"My luck's in," exulted Logan, and on the strength of that belief he hurried to the railroad–station. Again there was a telegram for him. Before he opened it he knew Lucinda would come. Her brief reply was: "Leave to–morrow. Arrive Tuesday. Love. Lucinda."

"Now, there's a girl!" ejaculated Huett, in great relief and satisfaction. Then he stared at the word love. He had forgotten to include that in either of his telegrams. As a matter of fact the sentiment love had not occurred to him. But still, he reflected, a man would have to be all sorts of a stick not to respond to one such as Lucinda Baker. Logan recalled with strong satisfaction that she had not been very popular with certain boys because she would not spoon. He had liked her for that. All at once his satisfaction and gladness glowed into something strange and perturbing. The fact of her coming to marry him grew real; he must try to think of that as well as the numberless things important toward the future of his ranch.

The next day, Saturday, saw Huett labor strenuous hours between daylight and dark. Sunday at the blacksmith's he packed and helped his friend rig a canvas cover over the wagon. This would keep the contents dry and serve as a place to sleep during the way down. Monday, finding he still had a couple of hundred dollars left, Logan bought horse and saddle, some tinned goods, and dried fruits, a small medicine case, some smoking tobacco, and last a large box of candy for his prospective bride.

This present brought him to the very necessary consideration of how and where he could be married. Here the blacksmith again came to his assistance. There was a parson in town who would "hitch you up pronto for a five dollar gold piece!"

Two overland trains rolled in from the East every day, the first arriving at eighty–thirty in the morning, and the second at ten in the evening. On board one of these today would be Lucinda Baker.

"Hope she comes on the early one," said Logan aloud, when he presented himself at the station far ahead of time. "We can get the 'hitch pronto' as Hardy calls it, and be off today."

It did not take Logan long to discover that the most important daily event in Flagg was the arrival of this morning train. The platform might have been a promenade, to the annoyance of the railroad men. Logan leaned against the hitching–rail and waited. Obstreperous cowboys clanked along with their awkward stride, ogling the girls. Mexicans, with blanketed shoulders, lounged about, their sloe–black eyes watchful, while handsome Navajo braves with colorful bands around their heads, padded to and fro with their moccasined tread. Lucinda would be much impressed by them, thought Logan.

The train whistled from around the pine–forested bend. Logan felt a queer palpitation that he excused as unusual eagerness and gladness. Small wonder—a fellow's bride came only once!

Presently Logan saw the dusty brown train, like a long scaly snake coiling behind a puffing black head, come into sight to straighten out and rapidly draw near. The engine passed with a steaming roar. Logan counted the cars. Then with a grinding of steel on steel the train came to a halt.

Chapter Two

Lucinda Baker's dreams of romance and adventure had been secrets no one had ever guessed; but none of them had ever transcended this actual journey of hers to the far West to become the wife of her girlhood sweetheart. Yet it seemed she had been preparing for some incredible adventure ever since Logan had left Independence. How else could she account for having become a school teacher at sixteen, working through the long vacations, her strong application to household duties? She had always known that Logan Huett would never return home again, and that the great unknown West had claimed him. For this reason, if any, she had been training herself to become a pioneer's wife.

She was thrillingly happy. She had left her family well and comfortable. She was inexpressably glad to be away from persistent suitors. She was free to be herself—the half savage yearning creature she knew under her skin. Steady, plodding, dutiful, unsentimental Lucinda Baker was relegated to the past.

Kansas in autumn was one vast seared rolling prairie, dotted with hamlets and towns along the steel highway. Lucinda grew tired watching the endless roll and stretch of barren land. She interested herself in her fellow–passengers and their children, all simple middle–class people like herself, journeying West to take up that beckoning life of the ranges. But what she saw of Colorado before dark, the gray swelling slopes toward the heave and bulk of dim mountains, gave her an uneasy, awesome premonition of a fearful wildness and ruggedness of nature much different from the pictures she had imagined. She awoke in New Mexico, to gaze in rapture at its silver valleys, its dark forests, its sharp peaks white against the blue.

But Arizona, the next day, crowned Lucinda's magnified expectations. During the night the train had traversed nearly half of this strange glorious wilderness of purple land. Sunshine, Canyon Diablo were but wayside stations. Were there no towns in this tremendous country? Her query to the porter brought the information that Flagg was the next stop, two hours later. Yet still Lucinda feasted her gaze and tried not to think of Logan. Would he disappoint her? She had loved him since she was a little girl when he had rescued her from some beastly boys who had dragged her into a mud puddle. But not forgetting Logan's few and practical letters she argued that his proposal of marriage was conclusive.

What changes would this hard country have wrought in Logan Huett? What would it do to her? Lucinda gazed with awe and fear out across this purple land, monotonous for leagues on leagues, then startling with magnificent red walls, towering and steep, that wandered away into the dim mystic blue, and again shooting spear–pointed, black–belted peaks skyward; and once the vista was bisected by a deep narrow yellow gorge, dreadful to gaze down into and justifying its diabolic name.

After long deliberation Lucinda reasoned that Logan probably would not have changed much from the serious practical boy to whom action was almost as necessary as breathing. He would own a ranch somewhere close to a town, perhaps near Flagg, and he would have friends among these westerners. In this loyal way Lucinda subdued her qualms and shut her eyes so she could not see the dense monotonous forest the train had entered. Surrendering to thought of Logan then, she found less concern in how she would react to him than how he would discover her. Lucinda knew that she had grown and changed more after fifteen than was usual in girls. What her friends and family had said about her improvement, and especially the boys who had courted her, was far more flattering than justified, she felt. But perhaps it might be enough to make Logan fail to recognize her.

A shrill whistle disrupted Lucinda's meditation. The train was now clattering down grade and emerging from the green into a clearing. A trainman opened the coach–door to call out in sing–song voice: "Flagg. Stop five minutes."

Lucinda's eyes dimmed. She wiped them so she could see out. The Forest had given place to a ghastly area of bleached and burned stumps of trees. That led to a huge hideous structure with blue smoke belching from a great boiler–like chimney. Around it and beyond were piles of yellow lumber as high as houses. This was a sawmill. Lucinda preferred the forest to this crude and raw evidence of man's labors. Beyond were scattered little cabins made of slabs and shacks, all dreary and drab, unrelieved by any green.

As the train slowed down with a grind of wheels there was a noisy bustle in the coach. Many passengers were getting off here. Lucinda marked several young girls, one of them pretty with snapping eyes, who were excited beyond due. What would they have shown had they Lucinda's cue for feeling? She felt a growing tumult within, but outwardly she was composed.

When the train jarred to a stop, Lucinda lifted her two grips onto the seat and crossed the aisle to look out on that side. She saw up above the track a long block of queer, high, board fronted buildings all adjoining. They fitted her first impression of Flagg. Above the town block loomed a grand mountain, black and white in its magnificent aloof distance. Lucinda gasped at the grandeur of it. Then the moving and colorful throng on the platform claimed her quick attention.

First she saw Indians of a different type, slender, lithe, with cord bands around their black hair. They had lean clear–cut faces, sombre as masks. Mexicans in huge sombreros lolled in the background.

Then Lucinda's swift gaze alighted upon a broad–shouldered, powerfully built young man, in his shirt sleeves and with his blue jeans tucked in high boots. Logan! She sustained a combined shock and thrill. She would have known that strong tanned face anywhere. He stood bareheaded, with piercing eyes on the alighting passengers. Lucinda felt a rush of pride. The boy she knew had grown into a man, hard, stern, even in that expectant moment. But he was more than merely handsome. There appeared to be something proven about him.

Lucinda suddenly realized she must follow the porter, who took her grips, out of the coach. She could not resist a pat to her hair and a readjustment of her hat. Then she went out.

The porter was not quick enough to help her down the steep steps. That act was performed gallantly by a strange youthful individual, no less than Lucinda's first cowboy, red–haired, keen–faced, with a blue dancing devil in his eyes. He squeezed her arm.

"Lady, air yu meetin' anyone?" he queried, as if his life depended on her answer.

Lucinda looked over his head as if he had not been there. But she liked him. Leaving her grips where the porter had set them she walked up the platform, passing less then ten feet from Logan. He did not recognize her. That failure both delighted and frightened her. She would return and give him another chance.

She walked a few rods up the platform, and when she turned back she was reveling in the situation. Logan Huett had sent for his bride and did not know her when she looked point–blank at him. He had left his post at the rail. She located him coming up the platform. A moment later she found herself an object of undisguised speculation by three cowboys, one of whom was the red–head.

Lucinda slowed her pace. It would be fun to accost Logan before these bold westerners. This was an unfortunate impulse, as through it she heard remarks that made her neck and face burn.

Logan had halted just beyond the red–haired cowboy. His gray glance took Lucinda in from head to foot and back again—a swift questioning baffled look. Then Lucinda swept by the cowboys and spoke:

"Logan, don't you know me?"

"Ah!—no, you can't be her," he blurted out. "Lucinda! It is you!"

"Yes, Logan. I knew you from the train."

He made a lunge for her, eager and clumsy, and kissed her heartily, missing her lips. "To think I didn't know my old sweetheart!" His gray eyes, that had been like bits of ice glistening in the sun, shaded and softened with a warm glad light that satisfied Lucinda's yearning heart.

"Have I changed so much?" she asked, happily, and that nameless dread broke and vanished in the released tumult within her breast.

"Well, I should smile you have," he said. "Yet, somehow you're coming back…. Lucinda, the fact is I didn't expect so—so strapping and handsome a girl."

"That's a doubtful compliment, Logan," she replied with a laugh. "But I hope you like me."

"I'm afraid I do—powerful much," he admitted. "But I'm sort of taken back to see you grown up into a lady, stylish and dignified."

"Wouldn't you expect that from a school teacher?"

"I'm afraid I don't know what to expect. But in a way, out here, your school teaching may come in handy."

"We have to get acquainted and find out all about each other," she said, naïvely.

"I should smile—and get married in the bargain, all in one day."

"All today?"

"Lucinda, I'm in a hurry to go," he replied, anxiously. "I've bought my outfit and we'll leave town—soon as we get it over."

"Well … of course we must be married at once. But to rush away…. It isn't far—is it—your ranch? I hope near town."

"Pretty far," he rejoined. "Four days, maybe five with oxen and cattle."

"Is it out there—in the—the … ? she asked, faintly, with a slight gesture toward the range.

"South sixty miles. Nice drive most of the way, after we leave town."

"Forest—like that the train came through?"

"Most of the way. But there are lakes, sage flats, desert. Wonderful country."

"Logan, of course you're located—near a town?" she faltered.

"Flagg is the closest," he answered, patiently, as if she were a child.

Lucinda bit her lips to hold back an exclamation of dismay. Her strong capable hands trembled slightly as she opened her pocketbook. "Here are my checks. I brought a trunk and a chest. My hand–baggage is there."

"Trunk and chest! Golly, where'll I put them? We'll have a wagonload," he exclaimed, and taking the checks he hailed an expressman outside the rail. He gave him instructions, pointing out the two bags on the platform, then returned to Lucinda.

"Dear! You're quite pale," he said anxiously. "Tired from the long ride?"

"I'm afraid so. But I'll be—all right…. Take me somewhere."

"That I will. To Babbitts', where you can buy anything from a needle to a piano. You'll be surprised to see a bigger store than there is in Kansas City."

"I want to get some things I hadn't time for."

"Fine. After we buy the wedding–ring. The parson told me not to forget that."

Lucinda kept pace with his stride up town. But on the moment she did not evince her former interest in cowboys and westerners in general, nor the huge barnlike store he dragged her into. She picked out a plain wedding–ring and left it on her finger as if she was afraid to remove it. Logan's earnest face touched her. For his sake she fought the poignant and sickening sensations that seemed to daze her.

"Give me an hour here—then come after me," she said.

"So long! Why, for goodness' sake?"

"I have to buy a lot of woman's things."

"Lucinda, my money's about gone," he said, perturbed. "It just melted away. I put aside some to pay Holbert for cattle I bought at Mormon Lake."

"I have plenty, Logan. I saved my salary," she returned, smilingly. But she did not mention the five hundred dollars her uncle had given her for a wedding–present. Lucinda had a premonition she would need that money.

"Good! Lucinda, you always were a saving girl…. Come, let's get married pronto. Then you come back here while I repack that wagon." He slipped his arm under hers and hustled her along. How powerful he was and what great strides he took! Lucinda wanted to cry out for a little time to adjust herself to this astounding situation. But he hurried her out of the store and up the street, talking earnestly. "Here's a list of the stuff I bought for our new home. Doesn't that sound good? Aw, I'm just tickled…. Read it over. Maybe you'll think of things I couldn't. You see we'll camp out while we're throwing up our log cabin. We'll live in my big canvas–covered wagon—a regular prairie–schooner, till we get the cabin up. We'll have to hustle, too, to get that done before the snow flies…. It's going to be fun—and heaps of work—this start of mine at ranching. Oh, but I'm glad you're such a strapping girl! … Lucinda, I'm lucky. I mustn't forget to tell you how happy you've made me. I'll work for you. Some day I'll be able to give you all your heart could desire."

"So we spend our honeymoon in a prairie–schooner!" she exclaimed, with a weak laugh.

"Honeymoon?—So we do. I never thought of that. But many a pioneer girl has done so…. Lucinda, if I remember right you used to drive horses. Your Dad's team?"

"Logan, I drove the buggy," she rejoined, aghast at what she divined was coming.

"Same thing. You drove me home from church once. And I put my arm around you. Remember?"

"I must—since I am here."

"You can watch me drive the oxen, and learn on the way to Mormon Lake. There I have to take to the saddle and rustle my cattle through. You'll handle the wagon."

"What!—Drive a yoke of oxen? Me!"

"Sure. Lucinda, you might as well start right in. You'll be my partner. And I've a hunch no pioneer ever had a better one. We've got the wonderfullest range in Arizona. Wait till you see it! Some day we'll run thirty thousand head of cattle there…. Ah, here's the parson's house. I darn near overrode! it. Come, Lucinda. If you don't back out pronto it'll be too late."

"Logan—I'll never—back out," she whispered, huskily. She felt herself drawn into the presence of kindly people who made much over her, and before she could realize what was actually happening she was made the wife of Logan Huett. Then Logan, accompanied by the black–bearded blacksmith Hardy, dragged her away to see her prairie–schooner home. Lucinda recovered somewhat on the way. There would not have been any sense in rebelling even if she wanted to. Logan's grave elation kept her from complete collapse. There was no denying his looks and actions of pride in his possession of her.

At sight of the canvas–covered wagon Lucinda shrieked with hysterical laughter, which Logan took for mirth. It looked like a collapsed circus–tent hooped over a long box on wheels. When she tiptoed to peep into the wagon a wave of strongly contrasted feeling flooded over her. The look, the smell of the jumbled wagonload brought Lucinda rudely and thrillingly to the other side of the question. That wagon reeked with an atmosphere of pioneer enterprise, of adventure, of struggle with the soil and the elements.

"How perfectly wonderful!" she cried, surrendering to that other self. "But Logan, after you pack my baggage in here—where will we sleep?"

"Doggone–it! We'll sure be loaded, 'specially if you buy a lot more. But I'll manage some way till we get into camp. Oh, I tell you, wife, nothing can stump me! … I'll make room for you in there and I'll sleep on the ground."

"Haw! Haw!" roared the black–bearded giant. "Thet's the pioneer spirit."

"Logan, I daresay you'll arrange it comfortably for me, at least," said Lucinda, blushing. "I'll run back to the store now. Will you pick me up there? You must give me plenty of time and be prepared to pack a lot more."

"Better send it out here," replied Logan, scratching his chin thoughtfully.

"Mrs. Huett, you'll change your clothes before you go?" inquired the blacksmith's comely wife. "That dress won't do for campin' oot on this desert. You'll spoil it, an' freeze in the bargain."

"You bet she'll change," interposed Logan, with a grin. "I'd never forget that…. Lucinda, dig out your old clothes before I pack these bags."

"I didn't bring any old clothes," retorted Lucinda.

"And you going to drive oxen, cook over a wood fire, sleep on hay and a thousand other pioneer jobs? … Well, while you're at that buying don't forget jeans and socks and boots—a flannel shirt and heavy coat—and a sombrero to protect your pretty white face from the sun. And heavy gloves, my dear, and a silk scarf to keep the dust from choking you."

"Oh, is that all?" queried Lucinda, soberly. "You may be sure I'll get them."

* * * * *

Hours later Lucinda surveyed herself before Mrs. Hardy's little mirror, and could not believe the evidence of her own eyes. But the blacksmith's good wife expressed pleasure enough to assure Lucinda that from her own point of view she was a sight to behold. Yet when had she ever felt so comfortable as in this cowboy garb?

"How'll I ever go out before those men?" exclaimed Lucinda, in dismay. A little crowd had collected round the prairie–schooner, to the back of which Logan appeared to be haltering his horses.

"My dear child, all women oot heah wear pants an' ride straddle," said Mrs. Hardy, with mild humor. "I'll admit you look more fetchin' than most gurls. But you'll get used to it."

"Fetching?" repeated Lucinda, dubiously. Then she packed away the traveling–dress, wondering if or when she would ever wear it again. The western woman read her mind.

"Settlers oot on the range don't get to town often," she vouchsafed, with a smile. "But they do come, an' like it all the better. Be brave now, an' take your medicine, as we westerners say. Yore man will make a great rancher, so Hardy says. Never forget thet the woman settler does the bigger share of the work, an' never gets the credit due her."

"Thank you, Mrs. Hardy," replied Lucinda, grateful for sympathy and advice. "I begin to get a glimmering. But I'll go through with it…. Goodbye."

Lucinda went out, carrying her bag, and she tried to walk naturally when she had a mad desire to run.

"Whoopee!" yelled Logan.

If they had been alone that startling tribute to her attire would have pleased Lucinda. Anything to rouse enthusiasm or excitement in this strange, serious husband! But to call attention to her before other men, and worse, before some wild, ragged little imps—that was signally embarrassing.

"Hey lady," piped up one of the boys, "fer cripes' sake, don't ya stoop over in them pants!"

That sally elicited a yell of mirth from Logan. The other men turned their backs with hasty and suspicious convulsions. Lucinda hurried on with burning face.

"Jiminy, she'll make a hot tenderfoot cowgirl," called out another youngster.

Lucinda gained the wagon without loss of dignity, except for her blush, which she hoped the wide–brimmed sombrero would hide. She stowed her bag under the seat and stepped up on the hub of the wheel. When she essayed another hasty step, from the hub to the high rim of the wheel she failed and nearly fell. Her blue jeans were too tight. Then Logan gave her a tremendous boost. She landed on the high seat, awkwardly but safely, amid the cheers of the watchers. From this vantage point Lucinda's adventurous spirit and sense of humor routed her confusion and fury. She looked down upon her glad–eyed husband and the smiling westerners, and then at those devilish little imps.

"You were all tenderfeet once," she said to the men, with a laugh, and then shook her finger at the urchins. "I've spanked many boys as big as you."

Logan climbed up on the other side to seize a short stick with a long leather thong.

"Hardy, how do you drive these oxen?" called Logan, as if remembering an important item at the last moment.

"Wal, Logan, thar's nothin' to thet but gadep, gee, whoa, an' haw." replied the blacksmith, with a grin. "Easy as pie. They're a fine trained brace."

"Adios, folks. See you next spring," called Logan, and cracked the whip with a yell: "Gidap!"

The oxen swung their huge heads together and moved. The heavy wagon rolled easily. Lucinda waved to the blacksmith's wife, and then at the boys. Their freckled faces expressed glee and excitement. The departure of that wagon meant something they felt but did not understand. One of them cupped his hands round his mouth to shrill a last word to Lucinda.

"All right, lady. Yu can be our schoolmarm an' spank us if you wear them pants!"

Lucinda turned quickly to the front. "Oh, the nerve of that little rascal! … Logan, what's the matter with my blue–jeans pants—that boys should talk so?"

"Nothing. They're just great. Blue–jeans are as common out here as flapjacks. But I never saw such a—a revealing pair as yours."