10,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Eland Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Greece has always had its admirers, though none seems to have cherished the Athenian tavernas, the murderous traffic and the jaded prostitutes, the petty bureaucratic tyrannies, the street noise and the heroic individualists with the irony and detachment of John Lucas. 92 Acharnon Street is a gritty portrait of a dirty city and a wayward country. Yet Lucas's love for the realities of Greece triumphs -for the Homeric kindness of her people towards strangers, for the pleasures of her tavernas and for the proximity of islands in clear blue water as a refuge from the noise and pollution of her capital city. This is Greece as the Greeks would recognise it, seen through the eyes of a poet.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

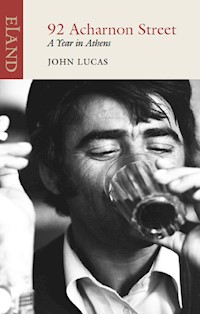

92 Acharnon Street

JOHN LUCAS

For my grandchildren, Amanda, Sam, and Macayla

‘Possess, as I possessed a season, The countries I resign’ A E Housman

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Illustrations

Epigraph

Introduction

Athens in Summer

92 Acharnon Street

Postcard from an Island

Discoveries

Among the Barbarians

The University

The Taverna on Filis Street

At Babi’s

And Now the Women

The Mini-Skirt

End of Day

Meeting Poets

Cultural Anthropology

A Winter Wedding

Faith and Reason: An Aeginetan Dialogue

Easter and Aegina

The Meeting on Acharnon Street

The May Election

An Honest Trade

Messene in July

Gathering

The Octopus

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Copyright

Illustrations

OTE state phone company

Overworked prostitute

Extinct species – instant images

Priests having lunch, Mavromixalis Street

Apsotsos, old kaféneion – hangout for all classes

Greek coffee

Yiannis with his guitar

Gypsies playing music outside kaféneion, AghiouKonstantinou St

Private parking

Barber-pasok

Schoolgirl going home

Intolerant, poetry-loving Andreas Papandreou’searly days at Megara Maximo

Local bus driver and family

Armchair intellectual – the rooster in the shop

Octopus

The publishers would like to thank Pamela Browne for permission to reproduce her photographs here. They were all shot in Athens in the late ’70s and early ’80s, either on assignment or as a flâneur. This is the first time that these images have been published.

‘Other countries may offer you discoveries in manners or love or landscape; Greece offers you something harder – the discovery of yourself.’

Lawrence Durrell, Prospero’s Cell

Introduction

TWO THOUSAND years ago, the poet Ovid was banished from Rome for upsetting Augustus Caesar. Quite what he had done to displease his emperor remains obscure, though the likeliest explanation is that something in Ars Amatoria prompted the imperial edict. Whatever the cause, Ovid was banished to Tomis on the west bank of the Black Sea. From there, in shock and bitter disappointment, he wrote his Tristia, describing the tedious years of exile and his boredom in an uncouth land. But if he hoped that this would soften Augustus’s obduracy, he was wrong. He was still in exile when he died, in AD18. Nothing he said could change Augustus’ mind, not even the claim that he, Ovid, was a Roman through and through and that, while you could change the skies under which a man lived, you couldn’t change his soul.

I was forty-seven years old when, in August 1984, I began a year of living in Athens. From early adulthood I’d wanted to go to Greece, but for a variety of reasons every plan fell through, and during the infamous period of the colonels’ junta (1967-74) visiting the country was simply not an option. Then, early in 1984, came an invitation to spend the academic year 1984-5 as visiting professor in the English department at the University of Athens. The details of how this came about and its consequences I leave until later. Here, I want to say only that the twelve months I spent living in Athens, while they may not radically have changed me, uncovered possibilities which, but for that year, might have remained hidden.

This is by no means to say that I approved of everything I found there. Bureaucracy, of which I encountered all too much, was, as it remains, a nightmare. Nothing was ever done as and when it should have been. Half the time you couldn’t even locate the official who was supposed to deal with whatever case you were required to present to him. Either you had just missed him or he would be in tomorrow. (Oh, no, he wouldn’t.) And if you did track him down, he would tell you that you had the wrong documentation. ‘But this is what I was told to bring.’ A dismissive shrug. ‘You must apply to Mr X.’ ‘But Mr X told me I must apply to you.’ A further shrug.

Much later, the poet and translator, Philip Ramp, tried to explain Greek bureaucracy to me. Philip and his wife Sarah, Americans who came to Greece in the late 1960s, are long-term residents on the island of Aegina, where my wife and I now have a small rented flat, and over the years we’ve become good friends. As well as making excellent translations of Greek poets, Philip has done much bread-and-butter work for Greek officialdom. He therefore knows more than most about the ways of the nation’s bureaucracy, and has no doubt as to why it is so uniquely awful. ‘In every other country’, Phil says, ‘bureaucrats are likely to be soulless, but after all they’re not paid to have souls. They’re paid to be efficient. And for the most part they are. You may not like them but they get the job done. They take pride in their work. But in Greece, nobody wants to be a bureaucrat. You go to see one and he’s not interested in discussing the reason you’re there. He wants to talk to you about poetry or art or music. And you know what, he’s almost certain to have a slim volume in his bottom drawer just waiting for a publisher. He’ll be OK as long as you keep to every subject but the one you came to him about, but as for the goddam money you’re owed by his department, or the piece of paper you need to get some work done, forget it.’

That Philip is right about this, I discovered not merely from my own experiences but from a tale told to me by the artist, Andreas Foukas. Just after he had gone to live on Aegina, Andreas took his car down to the port, left it while he did some shopping, and when he came back found he had been ticketed for illegal parking. Given that the police of Aegina are hardly ever to be spotted on the streets (although you can sometimes glimpse them at a waterfront ouzerie), this was a rare piece of bad luck. However, seeing the policeman nearby who had, he assumed, issued the ticket, Andreas went up to him and, as is the Greek way, began a lengthy explanation, amounting to an apologia, not to say exculpation, as to why he’d parked in the wrong place, stressing the fact that he was new to the island and that he would be certain not to transgress a second time. He also took care to lob in some compliments to the island and to its officials, including, naturally enough, its police force. After about twenty minutes of this the policeman tore up the parking ticket, and the two men, having shaken hands, went their separate ways.

Two weeks later Andreas drove down to the port town, parked in exactly the same spot and, when he returned from his shopping, found the same policeman waiting for him. This time there was to be no reprieve. Andreas had gone back on his word and now he was for it. Well, perhaps he could plead his case with the inspector? You can try, the now less-than-friendly policeman told him, but you will not succeed. He marched Andreas to the police station, where they found the inspector (asleep at his desk, so Andreas told me), the policeman reported Andreas’s two transgressions, and Andreas was then left to confront the inspector. As the policeman had forewarned, the inspector was not a man to be trifled with. Illegal parking was a most heinous crime and punishment would be exacted. Why, anyway, had Andreas dared to repeat the offence?

‘I was in search of canvas and paint.’

‘You are an artist?’

Yes, Andreas said, he was an artist.

A pause. The inspector, it transpired, was himself an artist. He would value Andreas’s opinion of a small water-colour he had recently finished and which he happened to have with him. The painting was produced, Andreas offered his professional judgement, much talk on subjects relating to art followed, and at the end of an hour the inspector and Andreas shook hands.

‘And my parking ticket?’ Andreas asked, as he made for the door.

‘Please to give it here.’ The ticket was torn in half and dropped into the waste paper basket.

I told this story to another Greek friend, George the hairdresser, who also lives on the island. For thirty years George made his money by cutting hair in High Wycombe, and then, with money he had carefully saved, he and his wife Nikki, both originally from Cyprus, came to Aegina and built a house there. Not long after we had got to know them, and when the house was gleamingly new, we were invited to look it over. In the living-room I noticed a framed letter from a royal hanger-on of the house of Windsor, thanking George for his poem on the birth of Charles and Diana’s first son. So George was a poet? Occasionally, he said, but it was not a major preoccupation. When he was not cutting islanders’ hair, or acting as guide to anyone who wanted to visit the dormant volcano on Methena (which faces across to Aegina from the mainland), or tending the gardens of the newly finished, ambitious monastery of Nektarios in the middle of the island, or helping out on his brother’s fruit farm on the far side of Aegina, or doing a thousand and one other things, he liked to fill his spare time by building model boats. When he told me about this I at first thought he meant ships in bottles. But then he took us to see them. I could hardly have been more wrong. Over the years George has constructed some forty large-scale models of boats that between them comprise a history of Greek maritime life, from ships that sailed to destroy Troy’s topless towers, through trading vessels of the classical period, Phoenician and Roman as well as Greek, to latter-day merchant ships. And not merely the vessels themselves. There are lovingly-made model cranes, blocks-and-tackle, bales, boxes, men and pack animals at work. For a while George set up a small museum – in fact a vacant shop – in Agia Marina, the unattractive pleasure-town on the far side of the island, but then a sudden and wholly unreasonable tax demand forced him out. For him island bureaucracy is a nightmare from which it is impossible to wake. Now the ships are kept in the basement of a second house he’s built at Alones (the word means ‘threshing floor’), a village not far from Agia Marina, and he shows people his exhibition for free, talking them through Greek history as he does so, especially the history of Greek seafaring. It isn’t what you’d expect of an English hairdresser. It is, though, what I have come to expect of many Greeks I know.

There is a kind of know-how/can-do that is taken for granted among them. This doesn’t always bode well. On more than one occasion I have come to grief over a friend who claimed to be able to solve any plumbing or electrical problem I presented him with. And it’s all but impossible to convince someone of the error of his ways. He is right, but right in a different way from the way you wanted. And his is the right right way. Philip gave me a hair-raising example of this insistence on infallibility. Some years ago a mainlander bought a plot of land near the foot of the island which had a spectacular view over the Saronic Gulf. He then hired an architect to draw up plans for a house he wanted built on the land he’d acquired, with windows looking out over the sea. A local builder engaged to have the house ready within twelve months and, having handed over a good deal of money, the man went back to Athens, safe in the knowledge that his house would be ready for him when he returned. Twelve months later he returned to the island. The house was ready and waiting. There was, however, a problem. Not a single window faced the sea. Instead, and without exception, each confronted a singularly drab piece of scrubland. And it wasn’t just the windows. Porch, patio, upstairs veranda, all faced the same way and that way was inland. The builder was sent for. Why on earth had he entirely ignored the architect’s plans? Why, oh, why had the house turned its back on the view its owner coveted? The builder shrugged. ‘I thought it looked better that way round,’ he said.

A refusal to follow approved or orthodox procedure was, I soon came to understand, commonplace, and could be infuriating. But it was the price to be paid for something I grew to love: a deep-rooted sense that individual lives are of paramount importance and not to be held to account by, let alone made the victim of, some god almighty officialdom. When I arrived in Athens in August 1984 I left behind me a nation that was growing increasingly cowed by such officialdom. One reason why the miners’ strike, which had just begun, found supporters even among those who might have been expected at the very least to look the other way, was that it embodied a protest against a new, particularly nasty element in British politics, or at least one that in post-war years hadn’t previously dared to show itself. The miners weren’t after all striking for more money or even better conditions. They were striking for the right to work. They were striking on behalf of what was still called the Dignity of Labour. And they were opposed by a set of men, and a woman, for whom such dignity meant less than nothing. Parkinson, Tebbitt, Baker, Clarke, Heseltine, Howe, and above all Thatcher were at one in their jeering contempt for the miners’ cause.

Nor were they alone. By 1984 something pretty horrible had begun to infect public life in Britain. You could smell its presence in the very language used by politicians, by business executives, by educational administrators. It was the language of sadism masquerading as masochism. It was about pain. ‘We must take some painful managerial decisions’ – meaning, we’re going to sack you. ‘It is time to bite the bullet’ – meaning, we’re the sawbones who will cut off your employment. ‘We must grasp the nettle’ – meaning, you’re the one who will be stung. And all of this was in the interest of being ‘leaner and fitter’. Down with isomorphs, away with endomorphs, from now on the world was to be made safe for mesomorphs. It can hardly be coincidence that this was precisely the moment when health clubs began springing up all over the place, where newly lean and fit executives and their epigoni were to be found pumping iron, burning rubber, and generally presenting hawk-like and ‘accosting profiles’ to the world. (Note the washboard stomach, the packed pectorals.) Nor can it be coincidence that this was the moment of ‘nouvelle cuisine’ – pay more, eat less – nor that those who knelt at the altar of the new orthodoxy tended to wear the ‘executive’ shirt that was suddenly all the rage. This was a shirt whose collar and cuffs were white, although the body of the shirt came in gamey reds, blues, or greens. See, I’m a sporty type, the shirt said, but I’m serious, too. More menacingly, it said, I may look like fun but don’t try messing with me. ‘What kind of prat wears a shirt like that?’ a friend asked in desperate, cod rhyme. Answer: the kind of prat perfectly happy to sack a few hundred men before settling down to a fruit juice and a slice of rye bread (unbuttered).

I don’t remember ever coming across such a shirt in Athens. I do remember, however, asking myself how many men it took to give you a piece of bread. In Babi’s taverna, my favourite eating place and a place to whose joys I devote a chapter, the answer was three. One to cut the bread, one to put the slices into a basket, and one to bring the basket to your table. I don’t imagine Babi gave any of them much if any money, but they all got fed, and customers’ tips would no doubt be shared among them. A shirt would have got rid of them without delay. Yes, but the rule of shirts didn’t operate in Babi’s taverna. Nor, as far as I could see, did it operate anywhere in Greece, not successfully, anyway. A change of skies indeed. And a change of soul? The pages that follow may provide an answer to that question.

Athens in Summer

‘Sweet hour. Athens reclines and gives herself

To April like a beauteous courtesan’

KOSTAS KARIOTAKIS

And at six o’clock this late, gamey August,

she sprawls under a blanket of sun, sweat

rankled with petrol fumes, cheap deodorants, dust:

everywhere litters of taxis squeal and fret

and root out fare among herds of lowing cars.

On a silver pool of café tables, pale

clouds of ouzo settle, milkily calm

as love achieved. Then daylight blows a fuse

and night swarms down the flats’ high cliff edges

past balconies where lamps suddenly fruit.

A teeming, seedy city, she feeds and farms

most present hungers, vine-roofed tavernas bale-

high with student politicos’ yelp and bark.

Attica’s pillars are lost in the sky’s soot

where all the streets ride on under the dark.

CHAPTER ONE

92 Acharnon Street

GEORGE PHONED one evening in May. ‘John, I have found you a flat. It is near where I myself live, and I may say that it will do very well. It is…’ At this point his voice was submerged under a series of howls and clicks. When the line cleared George wanted to know what had happened.

‘We’re probably being bugged,’ I said.

George was indignant. ‘That is not possible. Greece is a free country.’

‘Lucky you,’ I said. The bugging, if that’s what it was, was in all probability at our end. It was early summer, 1984, both Pauline and I worked for CND and were helping to run a support group for the striking miners; and Thatcher had given public approval to police and MI5 tactics for keeping tabs on anybody ‘not one of us’.

I explained this – no harm in letting the listeners know you’re onto them – but George was by now talking over my words. The flat had two bedrooms, lounge, bathroom, ‘and a proper kitchen’.

‘Sounds ideal,’ I said.

George was suddenly cautious. ‘I hope you will not be disappointed.’

‘I’m sure I won’t be,’ I told him. We said our goodbyes, and feeling mightily relieved at the prospect of a roof over my head for when I got to Athens, I put the phone down.

Three months earlier I had received, quite unexpectedly, a letter from the University of Athens, inviting me to spend a year there as Visiting Professor. (Lord Byron Visiting Professor of English Literature was, I think, the full title, and as I was to discover, the glory was all in that title.) I was both flattered and excited. But would my own university give me a year’s leave of absence? Yes, they would. So I wrote back to Athens saying that I’d be delighted to take up the invitation and asking for details of the appointment. No administration was involved, I was assured, and I would only be required to teach one course. Given that whatever reputation I enjoyed in academic circles had been acquired for a series of studies on nineteenth-century literature, especially Dickens, I assumed that the course would be on a subject related to my ‘specialism’.

Well, no. Professor R, head of English Studies, explained that he had a full complement of staff to teach the nineteenth century. However, he and his advisors would appreciate my offering a course on Shakespeare’s major plays. Puzzled, but not greatly put out – who after all wouldn’t relish the chance to throw in his tuppence worth on Romeo and Juliet, Measure for Measure, Hamlet, Lear, and The Tempest? – I went along with the request.

Good. And would I please send details about my date of birth, education, including degrees, major publications, academic career? Professor R would then at once complete the paperwork that would enable me to be put on the payroll as soon as I arrived in Athens. He closed by asking whether he could be of assistance in finding me suitable accommodation. ‘No,’ I told him, many thanks but I already had someone on the case.

A while earlier, by one of life’s great coincidences, a Mr George Dandoulakis had written to me from Athens, where he taught English at the Military Academy, asking whether I might be interested in supervising a doctoral thesis he proposed to write on the poetry of the Greek Liberation. Intrigued, but far from certain I was the right person to oversee such work, I suggested that he might like to come to Loughborough to discuss his proposal. And so, on a hot day in June 1982, George and I met for the first time.

I hope he won’t mind me saying that he looked far from comfortable in the heavy tweed suit he presumably thought appropriate to the occasion, wrapped tightly round his thickset body as it was, and his discomfort was increased by the lunchtime trout we were served at the University club, fish he’d never seen before, and which couldn’t be attacked in the Greek way. For one thing, it had more bones than he was used to, as an experimental mouthful made plain. And which pieces of cutlery were you supposed to use? It was seeing George hesitate at the bewildering choice of knives and forks placed before him that sharpened my sense of how cutlery is part of the world of conspicuous consumption, and how bloody daft we are to be cowed into thinking that a table isn’t properly laid until there are rows of silverware gleaming like surgical tools on each side of the place mat. Veblen was right. Who on earth needs fish knives and forks? Not George for sure. I think that meal must have been one of the few in his life from which he rose hungry.

No matter. I liked him, liked his ruddy-faced, round-eyed expression of watchful good cheer, the mobility of a look that could in an instant change from solemnity to laughter. Over coffee, we talked about his proposal, and I said that insofar as it involved English poets, pre-eminently Byron and Shelley, I’d feel confident that I could help him. The Greek poets, though, were a different kettle of fish. I knew nothing of importance about either Solomos or Kalvos, the two poets he would have to bring into his thesis. What to suggest? As far as I recall, we left it that I would make enquiries about possible extra supervision on the Greek writers. In the meantime, he might like to write a chapter outlining the years leading up to the War of Independence, and including any relevant material on poetic works of the time. Then we could take stock, and if either felt uneasy with the other, we could agree to part company before getting too deeply involved. Agreed? Agreed.

Over the following months work began to arrive, written out in painstaking longhand, and each new piece made me the more certain that this was a man who meant business. Then came the letter from the University of Athens. Naturally I discussed it with George, who naturally thought it a good idea for me to take up the offer. After all, that way he’d have his supervisor at hand – for by then I had agreed to take him on – and he would undertake to find me accommodation.

And so, in steamy August 1984 I saw for the first time the flat on Acharnon Street. George was waiting at the airport and quickly ushered Pauline and me through the NOTHING TO DECLARE exit, himself carrying the audiovisual machine he’d asked me to buy for him in England – ‘here they are too expensive’ – and which I’d wrapped in newspaper and forced into a plaid shopping bag, the kind of bag I associated with bottles of stout and scrag-end of lamb. ‘If you are stopped, say it is a teaching aid for your own use,’ George had instructed me, but the bored customs officials showed no interest in any of our luggage. They didn’t even query George’s presence at my side. Why should they? As soon as passengers had shown themselves within the arrivals hall, those waiting for them had simply pushed past the would-be restraining arms of the airport police and now whole families were assisting in the task of carrying off those many boxes, parcels, cases and bags without which, it seems, no Greek can travel. We climbed into the back of George’s scratched and badly dented Lada – ‘two or three crashes, nothing to worry about’ – and headed for the city.

Street after street of nondescript concrete-built apartment blocks stretched away into the surrounding hills, most of them with an unfinished or somehow provisional look about them: bare brick here, unglassed windows there, and everywhere steel rods sticking up from the flat rooftops. The road itself was littered with discarded newspapers, plastic bags, rusting coke tins; and floatings of cement dust drifted through what appeared to be rotting sunlight and was, so I would find out, caused by the worst atmospheric pollution in the Western world.

Then the car journey was over and a very few moments later Pauline, George and I were somehow crammed into a lift. ‘By the way,’ George said, as the lift groaned its way upward, ‘never use this if the electricians are going to strike. You may be trapped for hours.’

‘How will I know if they’re going to strike?’

He shrugged. ‘If I know, I will tell you.’ The lift stopped and we hauled my luggage out onto a bare landing before following him through a door whose lock had been recently and none too professionally fitted.

‘Well?’ he asked.

A three-piece suite of worn red plush took up most of the floor space of the tiny lounge. There was also, I noticed, a glass-topped coffee table and a set of straight-backed chairs with rush seats, lined up against a wall papered with a motif that looked very like elephants’ bums and facing a cheap wooden bookcase. But what really took my attention was the man who swayed uncertainly on top of a pair of stepladders that straddled the polished wood floor. ‘This is father,’ George said. ‘He is called Manolis. He is fixing your light.’

Manolis began a careful descent of the ladders. He must have been all of eighteen stone, perhaps more, and his round face and near-bald head, to which wisps of grey hair clung damply, was pink and beaded with sweat. A pair of grey trousers had been let out at the sides to fit around his enormous belly and above them he wore a short-sleeved cotton vest. We shook hands – his hand was wet – and when he smiled his mouth opened to reveal pink, bare gums. (I would later discover that he only ever put his teeth in for important family occasions.) But the smile was one of great sweetness and it reached up to his blue-grey eyes. ‘Welcome,’ he said, uttering the word with grave deliberation, and after a moment added, ‘Yannis.’ He pointed to me. ‘You Yannis,’ he said, ‘me Manolis.’

‘And this is Pauline,’ I said. Manolis shook hands with her and then once again shook hands with me.

He went over to the light switch, snapped it on and stared up at the bulb. The bulb, unlit, dangled from bare flex which was suspended from an elaborately carved ceiling rose, barely held in place by the one screw allotted it. Manolis tried the switch again. The bulb remained unlit. ‘No good,’ he said to us all and shrugged, an expansive world-weary heave of his shoulders. Then he gathered up his ladders and left.

The shrug intrigued me. ‘It looked as though your father was thinking the Greek for “dolce far niente”,’ I suggested. But George shook his head.

‘No,’ he said, ‘he was thinking the Greek for “oh fuck it”.’

I went to the balcony and looked out. And it was then I began to understand why George had been anxious about his choice of flat. In the first place it stank. Acrid fumes of cheap petrol and diesel, the hot smells of abraded rubber and brake shoes slammed against wheel rims, all drifted up from the traffic-clogged road on which my apartment block stood. As they rose they mingled with fumes from the oil-fired boiler in the basement. This was supposed to fuel the air-conditioning system during the summer and, in winter, supply us with central heating. But the air conditioning never worked and as for the central heating, I would learn that on the few occasions it did operate it provided only two ‘shots’ a day, and by the time the water had struggled up to my fourth-floor flat it did little more than take the worst chill off the radiators. God knows how people on the seventh, top, floor managed. But if the warm water didn’t rise, the boiler fumes most certainly did.

So did the stench from the butcher’s shop next door. Each weekday morning, early, the butcher would start to boil bones. Maggoty sweet smells crawled in through the flat’s open windows and clung to curtains, chairs, even my clothes. I thought of Mr Guppy and his friend and of their discovery of Krook’s death by spontaneous combustion, of the smouldering, suffocating vapour and thick, nauseating pool of grease into which Guppy inadvertently dipped his fingers. On bad mornings I could imagine pools like that forming on the floor of my flat. After some months the smells lessened and finally died away, although I could never believe the flat was entirely free of them. The butcher had shut up shop, I don’t know why. I do know that on that first afternoon of cloudy, oppressive heat, the smell from his shop seemed to be coming from some pit of final corruption.

Then there were the noises. I didn’t find out about all of these until later. For example, the frantic sexual activity in the flat above me only began in the late autumn. The woman who had moved into the flat was English, perhaps in her mid-thirties, had staring blue eyes, wore a variety of two-piece costumes – powder blue and damson were among her favourite colours – doused herself in cheap scent, and on the few occasions I met her was either accompanying a different man into or out of the apartment block or opening my mail. She was able to do this because each morning the postman would leave the mail for the entire block on a small desk inside the foyer. You had to go down and retrieve what was yours. The first time I did so the woman from upstairs was standing by the desk reading a letter. ‘It’s for you,’ she said accusingly. It was only when I’d climbed back upstairs to my flat that I allowed myself to wonder at her behaviour. Did she often open other people’s letters? Had she gone off with any? And why did she do it? Did she perhaps think that letters from England, even when not addressed to her, might ease the loneliness that stared from her eyes? I don’t suppose the men did. They never seemed to stay for more than an hour, although during that time there’d be noise aplenty: shrieks, shouts, doors slammed and, inevitably, what sounded like the thump of a pile driver and must have been the bed, tested to its limits.

Once, when we found ourselves alone in the lift, she told me her Greek husband was a ship’s engineer, away for months at a time. ‘I work as a hotel receptionist,’ she said, as though that explained something. Her voice was light, expressionless, ironed-out Cockney. ‘I’m teaching at the University,’ I told her. ‘Really?’ She was already bored. ‘I wouldn’t call that man’s work,’ she said, ‘not a real man anyway.’ After that, I never dared ask whether she’d stashed any of my post.

Other noises invaded my flat: of family quarrels, of occasional parties, of a small boy induced into screaming fits by a screaming mother, of a howling dog in the flat next door. But none of these could ever compare with the noises that came up from the street. Most of the year the windows stayed open. Since the air conditioning didn’t work, I had the choice of being slowly suffocated by fumes that leaked from the air ducts or of putting up with the street’s uproar. I chose the latter.

Somewhere in the world there may be a noisier street than Acharnon Street; but I hope not. A six-lane highway leading straight into the city centre, it was as busy at three a.m. as at three o’clock in the afternoon. All night long queues of nose-to-tail cars, lorries, coaches, taxis and motorbikes filled Acharnon Street, howling to a sudden halt (there was a set of traffic lights almost outside my window), blurting horns when red turned to green (you could just about hear them above the revving, farting engines whose drivers, in their macho determination to be first away when the lights changed, kept their accelerators fully pressed down, those in the front row always inching beyond the lights with the result that they couldn’t see when the change came and so relied on the cars behind them to signal the off); and then they’d career towards the next set of lights under a haze of exhaust fumes, tyres screeching on the road’s marble surface as though the drills of a thousand dentists had been wired up for some megafest of electronic sound.

As the year wore on I became inured to the night noises. Noise by day was different and once drove me nearly to distraction. I was in the flat that morning, trying to write, and as usual I had thrown open all the windows. Then the noise began. On this occasion it came not from Acharnon Street but from a narrow cut-through lane that connected Acharnon with the street parallel to it. The cut-through was supposed to be closed to all traffic except those using it for official purposes, including the garbage disposal cart that came around twice a week in order to collect the black plastic bags in which people put their rubbish. The bags were piled up beside the entrance to each apartment block and invariably split open before they could be collected, disgorging their malodorous contents across the pavement. On this particular morning the cart driver and his mates parked below my side window and went off to a nearby kafeneion for coffee and no doubt ouzo. They’d been gone all of five minutes when two cars drove up behind the cart and couldn’t get past. Of course they shouldn’t have been there, but you wouldn’t have guessed that from the persistent fury with which the drivers began to sound their horns. After ten minutes of this the driver of the cart and his mates returned, not, however, to move off, but to remonstrate with the car drivers for daring to use a lane forbidden to them. To make themselves heard above the blaring horns meant they had to shout very loudly indeed. Then the driver of the cart got up into his cab and began to sound his horn. At this, the car drivers got out of their cars and began to shout at him and his mates. More people arrived and began to shout at the car drivers, the driver of the cart, his mates, and at each other. This went on until the driver of the cart jumped down and shook hands with one of the car drivers, an act which proved to be the signal for a general hand shaking and slapping of backs; and then, when everyone’s hand had been shaken by everyone else, the entire group headed for the kafeneion. As they disappeared through its doors a car drove up behind the two parked cars and the garbage disposal cart and was unable to pass them. There being no sign that the cars or cart were about to move, the driver began to sound his horn. At that point I decided to cut my losses and go downtown to the British Council library.

Anyone who has lived in Athens for no matter how short a period of time will be able to cap that story. What you get on Acharnon is what you get at any major Athenian square or intersection. Twenty-four-hour wall-to-wall noise. The implosive crump as cars drive into each other, the two-tone bray of police vans and the wail of an ambulance’s siren; the street arguments as drivers leap from their vehicles to claim right of way, dispute who cut in on who, who deliberately parked in a certain place reserved for another, who did or did not indicate he wanted to turn right before turning left (or vice versa), whose mother had given birth to thirty devils, whose father was the Antichrist, whose sister deserved to marry a Turk, whose uncle had a sealed anus… The insults are as ritualised as the all-purpose swear word malakas and gestures: the spread five-finger thrust of dismissal, the two-handed chop at your own crotch (‘my balls’), the backward jerk of the head (‘a thousand times NO!’). Well, but if you could find all this anywhere in Athens, what was so special about Acharnon Street? Simple. Acharnon Street had brothels.