Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow Ltd

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Serie: A Chase in Time

- Sprache: Englisch

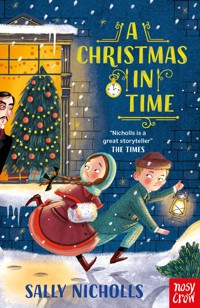

From multi-award-winning author Sally Nicholls, A Chase In Time is the first in a brilliant time-slip adventure series for 9+ readers, beautifully illustrated by Brett Hellquist. The old gilt-edged mirror has hung in Alex's aunt's house for as long as he can remember. Alex hardly notices it, until the day he and his sister are pulled through the mirror, back into 1912. It's the same house, but a very different place to live, and the people they meet need their help. Soon they're caught up in car chases and treasure hunts as they race to find a priceless golden cup - but will they ever be able to return to their own time?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 104

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To my Auntie Jean, with thanks for all the summers.

CHAPTER ONE

The boy in the mirror

The mirror hung by the stairs in Aunt Joanna’s hallway. It was tall and wide, with a gold frame full of curling leaves, and scrolls, and fat baby angels, and baskets of flowers, and twiddles. Aunt Joanna said it had once belonged to a French aristocrat, in the days before the revolutionaries chopped off all the aristocrats’ heads and turned their palaces into art galleries.

And once, when Alex Pilgrim was seven years old, he had looked into the mirror and another boy had looked back.

The boy in the mirror was Alex’s age, or perhaps a little older. He had light-brown hair and a sturdy sort of face. He was wearing a woolly blue jumper and grey knickerbockers. Knickerbockers, if you don’t know, are an old-fashioned type of trouser – shorter than long trousers but longer than shorts – worn by old-fashioned schoolboys in the days before boys were allowed real trousers.

This boy was brushing his hair in the mirror, rather hurriedly, as though he would much rather be doing something else. As Alex watched, he turned his head sideways and yelled at somebody out of sight. Alex couldn’t hear what he said, but it sounded impatient: “I’m doing it!” perhaps, or “I’m coming!” Then he put the hairbrush down and ran out of the frame.

Alex stayed by the mirror. It still showed Aunt Joanna’s hallway, but nothing in the hallway was quite as it ought to be. The walls were papered with yellow-and-green-striped wallpaper, and there was a large green plant he had never seen before and a white front door with coloured glass above the sill. It felt very strange not to see his own face looking back at him. He put out a hand, and there was a sort of ripple in the reflection. When the picture settled, there he was as usual: small, fair-haired, and rather worried-looking. There was the ordinary cream wall behind him. There was the ordinary brown door. Everything just as it always was.

Alex had never believed in those children in books who discovered secret passageways, or Magic Faraway Trees, or aliens at the bottom of the garden, and kept them a secret. Wouldn’t you want to tell everyone about them? What was the fun of a secret passage if you had no one to boast about it to?

But he knew that he would never tell his family about the boy in the mirror. Of course he wouldn’t. What would be the point? None of them would ever believe him.

After he saw the boy, though, the mirror became Alex’s favourite thing at Applecott House. He liked it more than the long garden with the high stone walls, and the blackberry bushes, and the apple trees. He liked it more than the three cats, and the rabbit in the hutch, and the playroom with the doll’s house, and the rocking horse, and the ship in the bottle, and the shelves of old-fashioned children’s books.

Alex loved beautiful things. He, his sister Ruby, and their parents lived in a scrubby little house on a scrubby little estate on the edge of an ugly red-brick town. Aunt Joanna’s house was about as different from Alex’s house as it was possible for an English house to be. It was big and old and rather grand – it always made Alex think of William’s house in the Just William books. It had iron gates with a stone ball on the top of each gatepost, and two staircases – a grand one for family and a poky one for the servants. Not that Aunt Joanna had any servants nowadays, of course. Nowadays, she ran a bed-and-breakfast business, and all the bedrooms were kept nice for bed-and-breakfast guests.

Aunt Joanna was really Ruby and Alex’s father’s aunt. Both of their parents worked busy jobs, which was OK most of the time, but made school holidays complicated. Ever since they were small, Ruby and Alex had gone to stay with Aunt Joanna for two weeks on their own every summer. Their parents paid for their bedroom, like proper bed-and-breakfast guests, and every evening they had to write on a piece of paper whether they wanted sausages or eggs or bacon for breakfast. They would help Aunt Joanna with the bed-and-breakfast work as well. Ruby’s favourite job was polishing the breakfast table, by sitting on the duster and skidding around on top of it. Alex’s was folding the bed sheets, Aunt Joanna on one side, him and Ruby on the other, the three of them coming to meet in the middle.

Applecott House was full of lovely objects. Aunt Joanna’s great-uncle had travelled all around the world collecting things, and most of the things he had collected had ended up in Applecott House. There were jade and ebony cabinets from Japan, statues of gods from Ancient Peru, and brightly coloured vases and plates from Turkey. Alex loved them all. But he loved the mirror best.

“Is it very old?” he asked Aunt Joanna, the summer he was ten and Ruby was twelve. “A hundred years old? Five hundred? A thousand?”

“Probably about two hundred and fifty,” she said. “It’s lovely, isn’t it? But I expect it’ll have to go when the house is sold.”

Because this was the last holiday Alex and Ruby would spend with Aunt Joanna. At the end of the summer, the house was to be sold and most of the lovely objects with it. Aunt Joanna would go and live in a little flat in Eastcombe, by the sea, where there would be no room for beautiful French mirrors or inlaid cabinets from Japan.

Everyone was very sorry about this. Alex minded so much about Applecott House being sold that it hurt. But even he didn’t mind as much as Aunt Joanna did. Aunt Joanna had been born in Applecott House. It was Aunt Joanna who had worked so hard to keep it. She had set up the bed-and-breakfast business, and done all the cooking and cleaning and washing and accounting, just so the house didn’t have to be sold. But at last, she had had to admit defeat. She was getting too old to do the work. And the house got more expensive to look after every year. Pipes kept bursting, and tiles kept falling off the roof, and mysterious things kept going wrong with the central heating.

“Ah, well,” she said to Alex, as he helped to water the garden. “I suppose it had to happen some day. Still, it’s a wrench, after all these years.”

“I wish I had millions and millions of pounds,” Alex said to Ruby that afternoon, as they sat in the garden. Ruby was reading. Alex was playing with a silver bottle he’d found in one of the cabinets. It had a round silver stopper, which he was trying to unscrew, but it didn’t want to come out. “I’d buy Applecott House and let Aunt Joanna live here as long as she wanted.”

“I wouldn’t,” said Ruby. “I’d buy a castle in France, with a swimming pool, and a private cinema, and a butler who did everything I asked him to, including homework, and a enormous library like Belle’s in Beauty and the Beast, and a garden so big I could hold rock festivals in it, and…”

But Alex didn’t care about any of those things.

“I want Aunt Joanna not to have to sell the house,” he said. “That’s all I want.”

As he said the words, the stopper came out of the bottle, so suddenly that he dropped the whole thing in surprise. A great quantity of dust and smoke poured out on to his lap.

Ruby said, “Eugh! What is it?”

“I don’t know,” said Alex. He tipped the bottle upside down, sending another cloud of dust mushrooming out.

Ruby coughed and waved her hands, and said, “I hope that’s not something important! What is it, someone’s ashes?”

“I don’t think so,” said Alex. He looked down into the bottle. There didn’t seem to be anything else inside. “Not a person’s ashes. It might be a hamster’s.”

“It’s old, anyway,” said Ruby. She took the bottle from him and frowned. “Yuck! Why don’t we ever get a bottle with a genie in it?”

“It’d be my genie if we did,” said Alex.

The rest of the day passed the way days at Applecott House always passed. They walked into the village and bought sweets at the Co-op. They picked blackberries from the garden and made a summer pudding for tea. They played a long game of Monopoly that ended, as usual, with Ruby owning half the board, and Alex nothing but two pound notes.

“To buy a cup of tea with,” said Ruby. “I’m charitable, me. I give to the homeless.”

“Huh,” said Alex.

It wasn’t until they were going up to bed that he remembered the bottle. There it sat, on the hall table. He picked it up, feeling vaguely guilty. Perhaps that dust had been something important.

“I wish you really were a genie,” he said sadly. Then he looked in the mirror, just in case there were any ghosts there tonight.

And there were.

In the mirror were two children. One was the same boy Alex had seen three years ago. Alex had grown, but the boy had stayed exactly the same age, only this time he was wearing a sailor suit and holding a paper bag. An older girl was standing beside him. The girl, who looked about thirteen, had long dark hair and a rabbity sort of face. She was wearing a blue dress, black stockings and a white pinafore. She was trying to take something from the paper bag – Alex guessed it must have sweets in it – and the boy was trying to stop her.

“Ruby,” said Alex, very cautiously. “Can you come over here? Like, now?”

“What is it?” said Ruby. Then she looked in the mirror. “Whoa.”

“You can see them,” said Alex. He’d been wondering if the whole thing might be a dream.

“Is it projecting from somewhere?” said Ruby. She looked around for a projector, but there wasn’t one. “Maybe it’s a TV screen,” she said. “Is Aunt Joanna doing it? Do you think it’s to help sell the house?”

“I don’t think it’s a TV,” said Alex. But he started to feel worried. Could Ruby be right? Could the one magic thing that had ever happened to him be something ordinary after all? “Look,” he said, and he touched the glass.

Except that there wasn’t any glass any more. His hand went right through the mirror. Ruby squealed.

“Alex!”

Alex tried to pull his arm back, but found that he couldn’t. It was like falling downhill in slow motion, except he was falling inside the mirror. He had to step forward to stop himself from tipping over. Ruby said, “Alex!” again, and then, “Alex, what’s happening?”

“I don’t know—” Alex said, and landed with a thump on his hands and knees.

“Ow!” said Ruby, behind him.

Someone screamed.

Alex looked up. He was on the floor in Aunt Joanna’s hall, but everything was different. There was yellow-and-green-striped wallpaper, and a white front door with coloured glass above it, and all the furniture was wrong. Standing in front of him were two children, who were both screaming. One was a girl with a rabbity sort of face, and long, dark hair with a white ribbon in it.

The other was a boy in a sailor suit.

CHAPTER TWO

The house behind the mirror

“Holy hell!” said Ruby. She scrambled up. “What just happened? And stop screaming!”

The boy and the girl stopped screaming. The boy scrambled backwards, so he was pressed as close to the girl as he could get. The girl put her arm around him. They both looked terrified.

“Are you witches?” said the girl.

“No,” said Alex. “I’m a boy, I’d be a wizard. But I’m just a boy. Where are we?”

“England,” said the boy. He looked about eight. He seemed reassured by Alex’s lack of wizardliness. “Suffolk. Dalton. Applecott House. I say, though – you can’t

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)