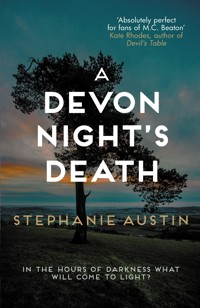

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Devon Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

In the hours of darkness what will come to light? In the Dartmoor town of Ashburton, reluctant antique shop owner and accidental amateur sleuth, Juno Browne, has cash-flow problems. So, when the mild and gentlemanly bookbinder, Frank Tinkler, rents a room above the shop, he seems like the answer to a prayer. At home, Juno accidentally disturbs intruders and shortly afterwards, one of them falls to his death from a viaduct. Was it accident, suicide or murder? When Juno recognises his accomplice as Frank's nephew, Scott, she decides to investigate .

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 417

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

A Devon Night’s Death

STEPHANIE AUSTIN

For Di

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

When you consider my nasty habit of discovering corpses, it’s curious that I’ve never found one when I’m walking the dogs. Dog walkers are the perfect candidates for finding dead bodies. Up early in the morning, they are the first to come across those things dumped secretly in the hours of darkness: a roll of old carpet, a dead microwave, a corpse. They stroll across empty waste grounds, past derelict buildings, their concrete walls garish with graffiti, or by stagnant canals, under bridges where skeletal shopping trolleys rise from shallow water. They amble along shady lanes edged with deep ditches, over rough pasture where nettles and yellow ragwort run riot, through thorny scrub, or in woods where leaf litter lies deep, the perfect place to abandon the odd corpse. To be honest, it’s usually the dogs, rather than their owners, who make the discovery. They possess the superior sniffing equipment.

A dog walker once found a body in Ausewell Wood, near Ashburton where I live. It was actually a skeleton in a sleeping bag, and presumed to be a camper or rough sleeper who’d succumbed to exposure. Poor bugger, he must have been lying there a long time. No foul play was ever suspected. It was reported in the local paper, but I don’t believe the identity of the unfortunate person was ever discovered.

I get up early each weekday morning and walk five dogs for their owners. The Tribe, I call them − Dylan, Nookie, Boog, E.B. and Schnitzel, in descending order of size. You might think that with an enthusiasm for digging and five times my sniffing power, the Tribe might have unearthed the odd cadaver on our woodland walks, snuffling about under all that undergrowth, but they haven’t.

I may have an unfortunate reputation for finding corpses − a member of the local police force laughingly refers to it as my hobby − but despite this, I have never discovered a dead body whilst out walking the dogs. Until now.

CHAPTER ONE

People who seem too good to be true usually are. I should have remembered that when I met Frank Tinkler. But when he walked into Old Nick’s at the end of a long, quiet afternoon, he seemed like the answer to a prayer.

‘This is a very interesting shop,’ he observed politely. He was somewhere in his sixties and sported a neatly trimmed grey moustache. He wore a blazer, and Panama hat, which he doffed on entry and which gave him the air of an old school cricket umpire. ‘What would you call it exactly, art and crafts?’

‘It’s really antiques,’ I jerked my thumb in the direction of my own selling space at the rear of the building, although antiques is a rather grand title for the odd assortment of stuff I currently have to sell, ‘and vintage clothes. And over there,’ I gestured towards the bookshelves, ‘we have second-hand books. We run a book exchange.’

‘Ah!’

I got the annoying feeling that he hadn’t come in to buy anything. That’s the trouble with owning an antique shop: as many people come in to sell you things as come in to buy. I’d just refused a woman who took it personally when I didn’t want to purchase her Royal Doulton figurines. As I tried to explain, however dainty and finely crafted they were, there is no market for porcelain ladies in crinolines at the moment.

I frequently wonder why I don’t sell Old Nick’s. I’d never wanted to own an antique shop but Nick left it to me in his will. Quite why is something of a mystery. I had only been working for him for a matter of months when he was killed. His family think he left it to me out of spite, although whether it was to spite them or me, I’ve never been sure. It was getting on for five-thirty, closing time and I didn’t want to hang around for a chat with this man if there wasn’t going to be a satisfying ping on the till at the end of it. ‘Were you looking for anything in particular?’ I asked, hoping to speed things up.

‘I heard a rumour you have spaces to rent.’

I must have beamed. I’ve had trouble renting out selling space. My last paying tenant, Fizz, only stayed a few months and by then I was glad to see the back of her. She now runs a swanky gallery of her own in North Street. ‘You heard correctly.’ I gestured towards an empty area by the bookshelves that I’d long been wanting to fill. ‘That space there is available—’

‘No, no.’ He cut me off with a firm sweep of the hand. ‘I need my own room. You see, I’ve always had a workshop at home, in the spare bedroom. But my daughter and her children have come back to live with us – lovely to have them with us, of course,’ he added hastily, ‘but I’ve lost my working space.’

‘I’ve got two rooms upstairs.’ These had once formed part of Nick’s flat and I led him up to what had been his former living room. It was also the room where he’d been murdered but I didn’t mention that.

He pointed to the sink in the corner. ‘That’s excellent. I need running water for my work.’

‘What do you do exactly, Mr … er …’

‘Tinkler,’ he answered with a charming smile. ‘Call me Frank.’

I pointed to myself. ‘Juno.’

‘I know who you are, Miss Browne. All of Ashburton must be aware of your exploits.’

‘What exactly do you sell?’ I asked, anxious to move on before the conversation turned to my unfortunate sleuthing activities in any more detail.

‘Marbled paper.’

I wasn’t sure I’d heard right.

‘I marble it myself,’ he went on. ‘I used to be a bookbinder by trade and I still do the odd bit of restoration work, but I’m retired really. The paper-marbling is just a hobby.’ He opened a book that he’d been carrying tucked under his arm since his arrival. ‘Here are some samples.’

I took the book from him. Each page was different, patterned with coloured inks to look like marble or rippled sand, feathers or leaves, or peacock tails in shades of red and gold. Some were just abstract works of art in wild swirling colours. I ran my fingers over the paper. ‘You do this by hand?’

‘Oh yes,’ he answered modestly.

‘It’s beautiful,’ I breathed. ‘Is there a market for it?’

‘Indeed, there is. I sell my work to bookbinders for the endpapers of bibles, atlases, legal and medical journals – that sort of thing – as well as for the antiquarian market.’ He looked around him. ‘This room would make a splendid workshop.’

‘It’s actually a retail unit,’ I pointed out. When I’d converted Nick’s old flat into rental space, I’d had to apply to the council for a change of use. I didn’t want to fall foul of the regulations.

‘I could sell these.’ He opened his blazer and pulled some greetings cards from his pocket, abstract patterns in bright, fresh colours. ‘I do these greetings cards and notebooks just for fun.’

‘They’re lovely.’ I took one from him. ‘We could display them downstairs.’ On some of those empty shelves, I added to myself.

‘I’d like to move in as soon as possible, if that’s all right with you. We need to discuss rent of course, but one or two questions first if I may.’

I was eager to discuss rent too. ‘Please, fire away.’

‘I often find myself burning the midnight oil, particularly if I’ve got a large demand to fill. Would it be in order if I were here working after hours, when the shop was closed?’

I nodded, anxious to please. ‘I can give you a key to the old flat door at the bottom of the stairs. It opens on to the alley at the side. Then you can let yourself in and out when you like without having to go through the shop.’

‘That would be perfect,’ he smiled. Then he added, after a slight hesitation, ‘Also, would you object if I put some kind of lock on this door, for when I’m not here?’

I wasn’t so sure about that. I didn’t like the idea of not being able to get into the room. What if he left a tap running and caused a flood in the shop downstairs? That’s exactly the sort of thing Fizz had been likely to do.

‘Some of the books I am asked to restore are quite rare volumes,’ he pointed out, ‘and naturally I am responsible for them while they’re in my care. And I notice you don’t seem to have a burglar alarm or any CCTV on the premises.’

He was right there. I hadn’t got around to affording any. ‘No,’ I admitted. ‘I suppose …’

Frank smiled. ‘I don’t smoke. I promise you I won’t start a fire.’

‘Well, in that case.’ A voice in my head still niggled, but somehow his polite, persuasive manner made my fears seem unreasonable. Besides, I was anxious to let the room and once we’d agreed a figure, he was ready with the rent. Paid up front, in fact. When I first opened the shop, I had intended to insist on a six-month tenancy agreement for anyone renting space but my experience with Fizz made me wary of lumbering myself with someone I couldn’t easily get rid of. Frank and I agreed on one month’s notice, either way.

I phoned Sophie after he’d gone, and Pat, as they’d both be on duty in the shop next day, to warn them of Frank’s arrival and make sure one of them gave him a key to the side door. They’re both too penniless to pay me any rent, so they man the shop in return for free working and selling space, an arrangement that allows me time for my proper job working as a domestic goddess, which basically means clearing up after other people.

‘He’s not going to play loud pop music all the time, is he?’ Pat demanded, ‘Like that last one.’

‘I wouldn’t think so. Frank strikes me as more of a Radio Three man.’

Pat grunted. ‘Is he going to be minding the shop?’

‘I haven’t asked him to,’ I admitted. ‘I thought we’d see how he settled in before I suggested leaving him on his own.’ At one time I’d thought everyone could take it in turns to man the shop, but Fizz had been a disaster.

‘Good thinking,’ Pat agreed. ‘Besides, Sophie and me manage things OK between us. And Her Ladyship comes in to cover now and again. I don’t think we want too many people left in charge.’

I stifled a laugh. By ‘Her Ladyship’, she meant Elizabeth, a friend who helped out in the shop when she wasn’t busy as a part-time receptionist at the doctors’ surgery. She’s a retired teacher with a gracious but crisp, no-nonsense manner, which seems to inspire Pat with a grudging sense of awe. ‘You’re probably right. Anyway, as long as you and Soph know he’s coming.’ I wouldn’t get to Old Nick’s until the end of the day myself, I’d be busy working.

It was a relief to close up, to escape the gloom of Shadow Lane and be released into the early evening sunshine. June had been hot and dry with very little rain and July was promising to be even hotter. I strolled down the narrow lane to my little white van. Every time I see it, it reminds me that it’s time it had a new paint job. Its white anonymity is a waste of advertising space. I used to call it White Van, till a friend christened it Van Blanc, which I prefer. I’d parked it in the shade, but I still felt as if I was climbing into an oven, the hot plastic smell of vehicle interior overwhelmed by the even stronger aroma left by the Tribe who got picked up in it every morning, the unmistakeable, comfy smell of dog.

I drove out of Ashburton, up the hill, a shady road through green woods, which eventually wound its way on to the open moor. I turned off at Druid Cross, towards my old friends Ricky and Morris’s place. They live in an impressive Georgian pile high above the town, looking down over the valley. From here they run their theatrical costume hire company. I’d phoned them earlier to see if I could borrow their shower. The boiler in my flat had gasped its last, leaving the entire house without hot water for days.

When I got there, the hallway was blocked by several large laundry hampers, costumes returned from a recent theatrical production and waiting to be unpacked. It’s the kind of job I often help Ricky and Morris out with.

After my shower, we all sat in the breakfast room, drinking wine, the garden doors flung open to let in the shimmering summer evening, my damp curls fluffing up horribly because I’d forgotten to bring my conditioner. I told them about my new tenant.

‘Tinkler?’ Ricky looked thoughtful. ‘That name rings a bell.’

‘Spare me the dreadful jokes. He seems very nice. Anyway, I need his rent so unless he’s a secret axe-murderer I’m prepared to take his money.’ I took a sip from my glass. ‘How’s the theatrical project going?’ They were planning to stage A Midsummer Night’s Dream in their garden at Druid Lodge. The rolling lawns and thick shrubbery make it the perfect setting for outdoor theatre. It was to be a community production with all the profits going to local charities.

Ricky moaned, performing a dramatic roll with his eyeballs. ‘I wish we’d never got involved now. We should never have applied for that funding.’

‘You mean the Arts Council Funding?’ I asked. ‘Why not? What’s the matter?’

‘It’s Gabriel Dark,’ Morris murmured.

‘Who’s he?’

‘He’s the professional director the Arts Council are sending us.’ He blinked, his round eyes solemn. ‘Of course, we don’t get a choice but …’

Ricky blew cigarette smoke down his nostrils. ‘I wish we were still directing the show ourselves.’

‘I don’t understand why you’re not.’ The original plan was that they would direct the play between them. They’ve done it before. They’re old hands at all this theatrical stuff, they’ve been doing it all their lives. But they’d learnt about an Arts Council Outreach Project that would pay for the services of a professional director from London.

‘We thought it would be good for the cast, being directed by a young, professional director,’ Morris explained, ‘someone who’s actually working in live theatre today—’

‘—instead of a pair of knackered old has-beens like us,’ Ricky finished for him.

‘You’re not has-beens.’ I kept quiet about the knackered old bit. But they were making a mistake. I was sure no one could do a better job than they could. ‘So, what’s wrong with this Gabriel Dark?’ I asked, apart from sounding as if he’d come from some kids’ book about wizards.

‘Well, I haven’t worked with him personally,’ Morris admitted, laying a plate of bread and olives on the table, overcome as always by the compulsion to feed me, ‘but he has a certain reputation.’

‘No one wants to work with him twice.’ Ricky laughed slyly, ‘That’s probably how he’s ended up doing outreach projects with amateur provincials.’

Morris returned from the kitchen with crackers and cheese. He cast Ricky an anxious glance over his little gold specs. ‘Perhaps it was just a case of you and him not getting on,’ he suggested, ‘after all, it was a long time ago.’

‘It was,’ Ricky agreed. ‘I was in his production of Hamlet, it must betwenty years ago. He was a real brat, fresh out of drama school, trying to make a name for himself.’

He lobbed his fag end into the garden and strolled to the table, walking his long fingers across the surface to pinch an olive.

‘Perhaps he’s changed over the years,’ Morris said optimistically.

Ricky shook his head. ‘There’ll be trouble, you’ll see.’

I was grateful I’d only volunteered to help with costumes. Acting is not my thing.

After a glass of Malbec, some excellent local cheese and an hour of listening to Ricky prophesying that their theatrical production was doomed, I made my excuses and came away.

The van rattled down the hill into Ashburton. I turned over the little stone bridge that crosses the shallow Ashburn and past a row of old weavers’ cottages. Drinkers enjoying the last of the evening sunshine lingered on the grass outside of the Victoria Inn, the pink sky behind the surrounding hills promising another fine day tomorrow. The air was still warm. I passed the town hall with its little clock tower, the ramshackle row of old shops. Then on an impulse, I turned and made a detour down Shadow Lane.

In the dimness of the narrow alleyway, Old Nick’s shone like a jewel, its pale green paintwork, its name on the swinging sign above the door picked out in gold, the displays in the windows highlighted by spotlights. I felt a little stab of pride, remembering what a shabby, run-down hole it was when Nick was alive. If I sold it, I could afford to buy my own home and stop renting the upstairs of Kate and Adam’s decrepit house. Except that they need my rent, and probably wouldn’t find another tenant without having to spend squillions doing the place up. And if I sold the shop, where would Sophie find a place to paint, or Pat sell the things she makes to raise money for the animal sanctuary she runs with her sister and brother-in-law? There’s the problem: it’s not just about me any more. And even if the shop is stuck down a dark alley where the sun never shines and tourists fear to tread, I want to make a success of it. And I had a new rent-paying tenant now, Frank Tinkler. Perhaps things were about to look up.

Kate appeared in the hallway as soon as I got home, glowing and beautiful and all mumsy-to-be, her thick dark plait hanging down over her shoulder. ‘Juno, can I have a word?’ There was a worried look in her eyes.

My own must have narrowed in suspicion. ‘What’s up?’ I demanded. ‘Are you OK?’

Instinctively, she stroked her rounded tummy. ‘Yes. I’m fine. It’s nothing like that.’

She smiled brightly. ‘The good news is, the boiler’s in.’

‘We’ve got hot water again. Excellent. And the bad news?’

Her words tumbled out in a rush. ‘Well, there’s been a slight accident in your bathroom.

‘Adam and I thought it was time you had a proper shower, so we’d asked the plumber to put one in over your bath—’

Yay, I thought. I’d be able to wash my hair without having to submerge myself in the bath every time.

‘But when he drilled the wall to fix the shower unit in,’ she plunged on, ‘most of the tiles fell off, bringing the plaster down with them and well … the whole bathroom needs plastering and retiling. We’ve got to get a plasterer in.’

‘Ah.’

‘The plumber had to rush off and he’s left it in a bit of a mess. Adam’s up there now. He was trying to clear it up before you got back.’

‘I’d better go and see how he’s getting on.’

‘It is a bit of a mess,’ she repeated with an apologetic shrug. ‘I’m just warning you.’

As I approached the door of my flat, I could hear a noise like someone shovelling shale. I called out ‘Hi!’ and detected muttered cursing. I poked my head gingerly around the bathroom door.

A bit of a mess was an understatement. The bath was full of broken shards of white tile and chunks of wet red plaster. Adam was on his knees with a dustpan, shovelling the mess into a garden bucket. Red dust coated his hair, beard and eyebrows and clung to his sweaty face. It hung in the air and covered the walls, as well as my soap and toothbrush. He squinted up at me and coughed. ‘Sorry about this.’

‘Hmmm. Shall I fetch some bin bags?’

‘They’re not strong enough.’

‘Well, there’s obviously not room for two of us in here,’ I said benevolently, ‘so I’ll leave you to it, shall I?’

He slid another dustpan full of broken tiles and dust into the rapidly filling bucket, groaning as he got off his knees. ‘I’ll just lug this down to the back garden,’ he croaked, wiping his face with his sleeve. ‘It’s only my eighth trip.’

‘I can tell it’s not your first by the state of the living room carpet.’

‘Sorry.’

‘It’s a bit late to put newspaper down now,’ I observed as he crunched across the living room, grinding gritty dust into the pile. ‘Perhaps we could consider a new carpet?’ I called out after him and heard more swearing as he lugged the skip downstairs.

I didn’t really care about the carpet. It’s threadbare in places with a beige swirly pattern that was probably the height of internal decor fifty years ago. And as a domestic goddess I spend too much time hoovering other people’s carpets to fuss with housework when I get home. But Daniel was coming at the weekend and, whilst I suspect my lover is not fussy either, we haven’t been together long and I don’t want to give him the impression that I wallow in filth. The idea that the bathroom might not even be operational was depressing. A cosy romantic soak surrounded by scented candles was obviously off the agenda.

‘Do you think this will be sorted out by the weekend?’ I asked as Adam reappeared with his empty bucket.

We stared together at the ruined bathroom walls, the chunks of missing plaster, the old lath strips showing underneath, and he puffed out his cheeks in a sigh. ‘We’ll do our best. The plumber’s promised he’ll come back and finish the shower tomorrow. It’s the plastering and retiling that might hold things up.’

I nodded sadly. There was obviously nothing more he could do. I grabbed a dustpan and brush from under the sink and whilst he lugged the next load of tiles and plaster downstairs, began to brush down the surfaces. Four buckets later the bath was empty.

‘I’ll wash it all down,’ I told Adam. ‘You’ve done enough.’ In the morning he had to be up even earlier than me, to cook breakfasts at Sunflowers. Kate’s morning sickness was preventing her from going in to help him in the cafe first thing and they couldn’t afford to pay for extra staff. If the dog walking hadn’t prevented me, I’d have gone in to help him myself. We wished each other goodnight and I set to washing down the bathroom. Finally, I lathered the dust off my soap. I decided to junk the toothbrush. Then I ran the vacuum cleaner over the living room carpet, the gritty dust rattling inside as if it was crunching on muesli.

It was only when I flopped into a chair at the end of all this labour, my thoughts turning towards a cosy read in bed, that I noticed the light on my ancient telephone answering machine winking at me like an evil red eye. Full of foreboding, I pressed play. It was Daniel’s voice, asking me to ring him back.

‘Is that Miss Browne with an “e”?’ he asked as soon as he picked up. The warmth in his voice made me smile.

‘It is, Mr Thorncroft. What’s up?’

‘I’m sorry, Juno, change of plan. I’m not going to be able to make it at the weekend.’

I ignored the sinking feeling. He was currently working in Ireland on a peat conservation project. ‘Stuck in the peat bog?’ I stifled a sigh. I could hardly complain when he’s trying to save the planet.

‘Up to my neck,’ he responded. ‘There’s a problem and it’ll be better if I stay here and get it sorted now.’

‘You’ll miss the concert,’ I reminded him. ‘I’ve bought tickets.’

‘Blast! Sorry, Miss B. Can you find someone else to go with?’

‘Expect so,’ I muttered glumly.

‘Then I’ll definitely be free to come over the following weekend when the caravan arrives.’

‘Caravan?’

‘I’ve bought one online. It’s being delivered to Moorview Farm a week on Saturday. I’ll need to be there for that.’

I cheered up a little. The farmhouse Daniel had inherited was a ruin and he’d been planning to buy a caravan so he could stay onsite whilst the building work was done. It was also intended to be a private place where he and I could satisfy our passion for each other without worrying about disturbing the slumbers of Kate and Adam downstairs. Now he’d finally got around to buying it. Despite the fact that I wouldn’t see him for another ten days I came off the phone feeling cheerful and celebrated by making hot chocolate and snuggling down in bed.

I’d barely opened my book before there was a light thump next to me and Bill meowed a welcome. He’d been keeping out of the way during the bustle in the bathroom, although the trail of pink paw-prints he left across the duvet meant he must have been sniffing around in there since. ‘You’re not my cat,’ I told him. ‘Why aren’t you downstairs with Kate and Adam where you belong?’ He didn’t have an answer, just curled up next to me, purring.

I tried a second question. ‘What can go wrong in a peat bog?’ But he didn’t have an answer for that either, just closed his one green eye, tucked his paws under and left me to my reading. I must have been tired. I woke up next morning with the bedside lamp still on and hot chocolate coagulating in its mug.

CHAPTER TWO

Even in the cool of the early morning, the sky pale and soft, a delicate mist hanging over grass silvery with dew, I could tell it was going to be a hot day. Later the sun would be fierce.

I walked the Tribe along lanes shaded by hedgerows thick with summer growth, with fresh hawthorn and hazel and flossy with the creamy heads of elderflowers. We walked in cool, green woods, where amongst the tumbled, mossy stones we could find streams to splash about in and the dogs could chase the sunbeams flickering on the water.

After I’d delivered the canines back to their various homes, then scrubbed my way around a client’s kitchen and bathroom, I’d begun to wish it wasn’t quite so warm. I emerged from their house squinting into the sunlight, sweaty and smelling slightly of bleach, longing for a cold drink before I headed off to my next appointment. I dropped in at the shop where I knew there were some cans in the fridge upstairs.

Unfortunately, my way to the kitchen was blocked. Frank had already started moving in and was in the process of dragging some metal shelving up the stairs towards his room. He had a helper, a good-looking fella of about twenty, with short-cropped fair hair, who was pushing from the other end. He introduced him as Scott, a nephew of his. I decided I’d better forget about the cans in the fridge. Sophie was at her easel, rapt in contemplation, not of her current painting, but the muscles rippling beneath Scott’s fitted t-shirt. I snapped my fingers beneath her nose and she jumped, grinning at me as I waved goodbye.

On any weekday morning the corner of North Street is alive with shoppers and busy with delivery vans half-parked on the pavement trying to unload outside of the shops. I nipped into the Co-op to buy myself a drink and a sandwich for lunch, almost bumping into a woman in the doorway as I came out. ‘Aren’t you Juno Browne?’ she smiled.

She was a slim, middle-aged lady with mild blue eyes and wispy fairish-brown hair. I didn’t recognise her. ‘Um … yes.’

‘You don’t know me,’ she added, seeing my blank look, ‘but my husband has just rented a room in that lovely shop of yours. Frank Tinkler?’

‘Oh, you’re Frank’s wife? Hello!’ We exchanged smiles and handshakes. ‘Yes, I’ve just seen him, he’s just moving in.’

‘I’m Jean.’ She must have been a bit younger than Frank, with the same well-mannered charm, a slightly faded English rose-type dressed in a summery white blouse and floral skirt.

‘I hear you’re claiming back your spare bedroom,’ I said.

‘Not just the spare bedroom,’ she laughed, ‘the conservatory, the utility room. The boxes full of old books are bad enough, but I’m fed up of finding sheets of marbled paper spread out to dry everywhere. I don’t know why he can’t do it all in the garage, but he says it’s too damp. It’ll be such a relief to get rid of all hisstuff.’

We were interrupted by a breathy Welsh voice as an ample, fair-haired woman wearing a dark business suit one size too small bore down on us from across the street. ‘Hello, Mrs Tinkler!’ she cooed as I groaned inwardly. Sandy Thomas, who worked in the office of the Dartmoor Gazette, fancied herself as an ace reporter and was a right pain in the arse where I was concerned. ‘Hello, Juno!’ she added, as if we were old friends. ‘How is Frank, Mrs Tinkler?’ she asked solicitously, ‘has he got over that nasty business from last year?’

I could see Jean Tinkler stiffen. Her laugh evaporated. ‘Yes. Yes, he’s fine, thank you.’

‘No lasting consequences, I hope?’

‘No. No, Frank was very lucky. He got away with a few bruises, he really wasn’t hurt, you know.’

I must have been looking as baffled as I felt because Sandy explained, ‘Mr Tinkler was the victim of a hit-and-run driver last year, right here in Ashburton.’ She turned to Jean for confirmation. ‘On Eastern Road, wasn’t it? He was just crossing the road—’

It was obvious Jean Tinkler didn’t wish to discuss it. ‘Would you excuse me?’ she asked, cutting Sandy off short. ‘I really must get on. Nice to have met you, Juno,’ she added and hurried away.

For a moment we watched her departing back. ‘What happened?’ I asked.

Sandy could always be relied upon for information. ‘Well, like I said, Frank Tinkler was crossing Eastern Road and this driver nearly knocked him down. He managed to jump out of the way just in time. He was a bit bruised and shaken, that’s all.’

‘But the driver didn’t stop?’

‘No, went speeding off, apparently.’ She dropped her voice and laid a conspiratorial hand on my arm. ‘I’ll tell you one thing, though …’

‘What?’

‘There was a witness, been chatting on the pavement with a friend, saw the whole thing, swore that the driver aimed the car at him deliberately.’

‘Tried to run him over?’

‘Yes. But swerved at the last moment, the witness said.’

‘Perhaps the driver simply didn’t see him until it was almost too late.’

‘No, no,’ Sandy assured me with a solemn shake of her head, ‘the witness was sure it was deliberate.’

I could see it made a better news story that way. ‘But this witness didn’t manage to get the car’s number?’

‘Unfortunately, not,’ she added sadly. ‘I think he was more concerned with making sure Mr Tinkler wasn’t injured. So, I don’t suppose we’ll ever know what really happened.’ She sighed and then slanted a glance at me. ‘What about you?’ she asked, her little newshound’s nose twitching. ‘Aren’t you investigating anything at the moment?’

When I’d escaped from Sandy, unable to convince her that I don’t investigate things, they just happen to me, I made my way up to Stapledon Lane. My long-standing client, Mrs Berkeley-Smythe, has a cottage there. She spends most of her life away on cruise ships and her garden needs regular watering during her absence. She’s had the lawn paved over, in favour of fashionably expensive stone, so there’s no mowing to worry about, but terracotta pots dry out quickly and I didn’t want Chloe to arrive home to find her cosmos fried to a frazzle. Why she wants to bother with so many plants when she’s so rarely on dry land to admire them, I can’t imagine, but in this dry heat a thorough soaking would only last them for a day or two. Recently, she’s taken to statuary. A serene stone buddha sits in the shade of a Japanese maple and an impossibly large and happy frog smiles amongst the ferns in a shady corner. I’d reeled out the hosepipe and was just filling up the ornamental birdbath, a bronze-coloured shell mounted on an ornate pedestal, when my mobile phone rang. I reduced the gushing hosepipe to a dribble. It was Ricky. ‘What’s up?’ I asked.

‘Sorry to bother you, Princess, but I don’t suppose you could do us a favour?’

‘Anything for you,’ I responded recklessly.

‘It’s that bloody Gabriel Dark,’ he explained. ‘He’s coming down from London this afternoon to talk about the Shakespeare project. He wants to take a look at the performance space before he arrives to start rehearsals. ’Course, we’ve had to offer to let him stay the night. But the point is, the old Saab is in for a service and won’t be ready till five-thirty, and he needs picking up at the station at four so …’

I glanced at my watch. ‘I can do it after I’ve finished this. Where will he be? Exeter?’

‘No, Newton Abbot. Thanks, darling, you are a star.’

‘As long as he doesn’t mind riding in the doggy van.’

Ricky snorted. ‘He’s lucky to get a ride at all. I’ll ring him and let him know, tell him to look out for a flame-haired goddess.’

I ignored this. ‘And how will I recognise him?’

‘That’s easy,’ Ricky chuckled. ‘Just look for the horns and tail.’

Despite the satanic appearance Ricky tried to give him, Gabriel Dark was a normal-looking human being of about forty, shortish, with floppy black hair, blue eyes and a charming smile. He was quite attractive, actually. Don’t let the boyish grin fool you, Ricky had warned me, he’s got an ego the size of Jupiter. That’s rich, coming from Ricky. His description of me must have been more accurate because Gabriel Dark approached me as soon as I reached the station entrance. There weren’t any other six-foot redheads about.

‘Juno?’ he asked, and when I nodded, proffered his hand. He looked me up and down as we shook. I must have looked a treat in my old gardening trousers. ‘Please tell me you’re auditioning.’

‘No, sorry.’

‘But you’d make a perfect Helena.’

I admitted to having studied the play at college and pointed him in the direction of my old Van Blanc. ‘I hope you’re not allergic to dogs, I take five of them out in this every morning. Ricky and Morris send their apologies for not picking you up, by the way. Their car’s being serviced.’

‘So they explained. Listen, Juno,’ Gabriel slid into the passenger seat and buckled up his seat belt, ‘help me out here, will you? Can you tell me a bit about my hosts, the initiators of this project? This … um …’ he unfolded a piece of paper from the leather manbag he carried, ‘Morris Greenbaum and Ricky … erm … Steiner, is it?’ he frowned as he donned a pair of designer reading specs.

‘You’ve met Ricky before,’ I reminded him. ‘He was in your production of Hamlet years ago.’

Gabriel frowned. ‘The name doesn’t mean anything.’ He glanced at me sideways. ‘You don’t know which part he played?’

‘The ghost, I think.’

He shook his head as if he was still at a loss. I was amazed. How could anyone forget Ricky, even if the production was twenty years ago? Apart from the fact he’s always memorably rude, Ricky had the charismatic good looks you don’t forget. He still has, in a grizzled kind of way.

‘Nope, perhaps I’ll recognise him when I see him.’

There was something about his careless shrug as he spoke that got my antennae twitching.

I suspected that he remembered Ricky perfectly well, but for some reason chose to pretend he didn’t.

‘I understand they’ve got some kind of theatrical background,’ he went on dismissively. ‘I really should have studied their info,’ he admitted, waving his piece of paper about, ‘but I haven’t had a minute.’

He’d just had three hours sitting on a train but perhaps he’d been occupied with other things. I explained that Morris sang and Ricky played the piano and that though they claimed to be retired they still entertained as a double act, Sauce and Slander.

Gabriel groaned. ‘They sound dire!’

‘No, actually, they’re very funny,’ I responded, stung on their behalf. ‘They write satirical songs. They only perform to raise money for charity these days. And of course, they make costumes.’

Gabriel Dark raised an eyebrow. ‘Do they now?’

He really hadn’t read any of that piece of paper. ‘They run a theatrical hire company. They send costumes to theatre companies all over the place.’

‘Do you think they’ll make costumes for this show?’

I had to smile then. ‘Let’s put it this way, they’ll be very offended if they’re not asked.’

Gabriel laughed. ‘That’s a relief. I thought I might have to find some old dear with a sewing machine and get down on bended knee.’

His phone trilled The Ride of the Valkyries and he slipped it from his pocket. He frowned briefly at the screen but didn’t take the call and returned the phone from whence it came.

‘Is this your first community production?’ I asked.

He grimaced. ‘I’m afraid I drew the short straw.’ He made it sound as if he’d had no choice in the matter. His phone went, it was the Valkyries again. This time he didn’t bother to look at it. I asked him about his own career and he launched into a long story about how he’d been blighted by a succession of short-sighted theatre administrations and ignorant audiences. Eventually he asked about me. What did I do, apart from driving dogs around?

‘I actually walk the dogs,’ I explained. ‘I’ve had my own business as a domestic goddess for several years now, basically cleaning and caring, with a bit of dog walking and gardening thrown in. Then I inherited an antique shop.’

‘Wow!’ he grinned. ‘That’s cool.’

‘Well, it is and it isn’t. At the moment I’m trying to keep both businesses going at once.’

‘Can’t you give one of them up?’

‘Neither of them makes enough money on its own.’

‘Ah!’

His phone went a third time. The Valkyries were getting impatient. He grinned apologetically. ‘I’d better take this … Yes?’ He listened for a moment, then hissed into the phone. ‘How did you get this number?’

I concentrated on the road ahead, trying not to look as if I was eavesdropping. After a few more moments Gabriel ended the call. ‘I can’t talk now.’ He flicked me an embarrassed glance as he returned the phone to his pocket, ‘These damned call-centre people, they never stop pestering, do they?’ He laughed weakly and I murmured sympathetic noises. He lapsed into silence as I turned off the main road into Ashburton. From the way he was frowning and chewing his lip. I’d have said the damned call-centre people had rattled him for some reason. But as I drove through the narrow streets of the town, he began to take notice. ‘This place really is old. I had no idea.’ I restrained myself from launching into its history, fascinating though that is. I just let him soak it all up, its steep roofs, crooked beams and stone archways spoke of its age more eloquently than I could. I turned up the hill, the steep road taking us towards Druid Cross through a long green tunnel of trees. Sunlight glimmered through the leaves in specks and freckles of gold. ‘Wow!’ Gabriel cried, delighted, ‘This is real fairy glade stuff.’

I turned along the lane, the hedgerows parting suddenly, a five-bar gate allowing us a glimpse of gold fields ripe with corn dipping down to the town below, the towers of St Lawrence Chapel and St Andrew’s church rising above huddled rooftops. Shortly afterwards, we swung in through the gates of Druid Lodge and followed the curving drive through the gardens. Then the house came into view and hit Gabriel full wallop with its grand Georgian architecture. He was momentarily silenced. ‘My God, this isn’t where they live?’ The van crunched to a halt on the gravel outside. He gazed at the row of long windows, the columns and the stone portico above the front door. ‘Lucky bastards!’

‘They share it with several thousand costumes,’ I reminded him, but he wasn’t listening. He got out of the van and stood gazing at the white frontage of the house, one hand shading his eyes. ‘It’s fantastic,’ he muttered enviously.

‘Let’s go inside. Ricky and Morris are dying to meet you. And I’m sure they’ll give you the grand tour if you want it.’

‘I certainly do,’ he told me, and the Ride of the Valkyries started up again in his pocket.

Morris begged me to stay for dinner. It wasn’t the prospect of his wonderful cooking that made me agree to his invitation as much as the note of desperation in his voice and the pleading look in his eyes.

Ricky already had a dangerous look about him. Gabriel was insisting that he couldn’t remember his Hamlet’s Ghost at all. ‘Are you sure it was my production you were in?’

‘It was set in a concrete bunker,’ Ricky retorted. I couldn’t help noticing his voice had lost its slight London twang and assumed the richer, fruitier tones he used on stage.

‘Oh yes, yes!’Gabriel clicked his fingers annoyingly. ‘I do remember vaguely.’

Ricky had photographs at the ready and thrust them under his nose. There were colour pictures of him dressed as the ghost, magnificent in ghostly silver make-up and full body armour, and several black and whites taken at a rehearsal, with one of him and Gabriel looking as if they were in the midst of a heated argument.

Gabriel took them from him, leafing through. ‘Of course!’ He nodded as if it was all a wonderful memory that had suddenly come flooding back to him. ‘How could I forget? A towering performance, Ricky! Bloody wonderful!’

Ricky is nobody’s fool. He’d predicted that Gabriel would wind him up and I could tell by the narrowing of his eyes and the grim set of his jaw that he wasn’t wrong. Morris began nervously polishing his spectacles. I laid a comforting hand on his arm and promised I’d come back in time for dinner. I wanted to change, and I always try to pop into Old Nick’s before closing time.

‘I’ll be back at seven,’ I whispered to him. ‘Try to keep the lid on.’

CHAPTER THREE

I’d been so distracted by picking up Gabriel Dark that I’d almost forgotten about Frank Tinkler moving in. Sophie was cashing up when I arrived, her dark head bent low as she counted piles of change for the float, her lips moving silently. She might be a brilliant artist but cashing up takes her ages. Frank had moved in all his shelving and bits of equipment, she told me. ‘He’s bringing his inks and papers tomorrow, and he’s promised he’ll show me how to do marbling when he’s all set up.’ She smiled. ‘He’s nice, Frank, isn’t he? Sort of old-fashioned and very polite.’

‘Gentlemanly,’ I agreed. The idea that someone might seriously aim a car at him with the intention of killing him seemed ridiculous the more I thought about it. Perhaps whoever had witnessed the incident enjoyed dramatising in the same way Sandy Thomas did.

Sophie’s brows drew together in a frown. ‘Did you tell him he could put a padlock on his door?’

I nodded. ‘Some of the books he repairs are valuable, apparently.’

Her dark eyes widened. ‘They must be encrusted with gold, judging by the size of that padlock.’

We went upstairs so she could show me. The door to Frank’s room stood open, there was no need to lock it yet as all it contained were racks of empty shelving, a table and chairs and a pile of wide, shallow trays that I assumed were used in marbling. But a steel plate had been screwed to the door with a thick metal hasp from which hung a very chunky padlock. I weighed it in my palm. ‘I didn’t realise it was going to be this big.’ It wasn’t the sort of padlock you opened with a key either. It had a combination on it, a row of numbers set on tiny rollers; you needed to line them up in the correct sequence for it to open. ‘He’s obviously very security conscious.’

Sophie puffed out her cheeks, ‘Seems a bit over the top to me.’

I glanced into the room and noticed a heavy iron safe on the floor in the corner, its door wide open. It was empty inside. ‘That must have taken some heaving up the stairs.’

‘It did,’ Sophie nodded. ‘It was a good job he had help from Scott. He couldn’t have managed it on his own.’

‘He must be expecting to take more money than the rest of us do. Still, if it keeps him happy. After all, we don’t have a burglar alarm and we need his rent.’ I turned to frown back at her as we trod downstairs. ‘You haven’t mentioned that you and Pat don’t pay any, have you?’

‘Of course not.’

‘Good. He doesn’t need to know what our arrangement is. Just keep it under your hat.’

I dropped Sophie off at her mum’s and went home to change. When I arrived back at the flat, I found a transformation had taken place in my bathroom – or at least, in half of it. The shower had been put in over the bath, a glass screen fitted, and one wall was clad in what looked like marble panels, white with a sparkly gold fleck. They were actually made of plastic, but I wasn’t about to complain. They looked clean and modern and were a great improvement on broken tiles and missing plaster in the rest of the room. I bounced downstairs to knock on the kitchen door.

‘It’s good stuff, isn’t it?’ Kate said brightly. ‘The plumber suggested it. It’s cheaper and quicker than getting new tiles. He just sticks the panels straight on the wall. Is the colour OK? I didn’t think you’d want pink. He says he’ll finish it tomorrow.’ She grinned, ‘In time for the weekend.’

I sighed. ‘Daniel’s not coming now. There’s trouble at t’bog.’

‘Oh, what a shame!’ She disappeared for a moment and reappeared with a small consolation prize wrapped in foil, a leftover offering from Sunflowers. ‘Bombay pie,’ she explained, ‘curried veggies with chickpeas and paneer.’

‘Thank you.’ It was only a small package but a goodly weight. A little while ago Kate and Adam were thinking of selling Sunflowers and, thank God, they’d changed their minds. Without their cafe leftovers I might starve.

Half the walls in the bathroom might still be bare and crumbling plaster, but the new shower worked. I lingered under it for ages, holding my hair up, enjoying the rising steam, the tingling needles of hot water pouring over my neck and down my spine. Then I washed my hair, towelled it dry, changed and made it back to Druid Lodge, only ten minutes late.

I needn’t have hurried; dinner was not yet on the table. Gabriel, Ricky and Morris were in the garden, surveying the potential performance space.

‘The main acting area is down there where the lawn levels out, with the lake and woods as a backdrop.’

‘We thought it would look so pretty,’ Morris added, ‘with lights in the trees reflecting on the water.’

‘Pretty,’ Gabriel repeated, as if this was an entirely alien concept, his palms closed together in front of his mouth, eyes narrowed, as if he was deep in thought.

‘And it would be so lovely,’ Morris continued with a catch of sadness in his voice, ‘if we could make it a place of happy memories again.’ He began polishing his glasses, always a sign of stirred emotion with Morris. Not long ago the lake and the wood had been the scene of tragedy. A body had been found floating in the water and the young gardener, Luke, who had transformed the lake and little woodland from a dark, weed-choked, overgrown wilderness, to an airy glade filled with dappled light, had committed suicide.

‘Actually, I like the lake,’ Gabriel declared after a brief silence. ‘Wouldn’t it be great if the fairies could rise up out of it like water spirits?’