Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Devon Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

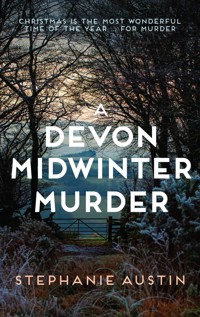

Christmas is the most wonderful time of the year ... for murder As amateur sleuth Juno Browne's Sunday gets to a chilly start in the delightful Devon town of Ashburton, a murder is brewing. As always seems to happen, Juno is in the wrong place at the wrong time, and she discovers the body of Bob the Blacksmith, his dead hands entwined with a sprig of elder. Juno begins to see links with previous 'accidental' deaths, although her way through the cloud of suspicion is further obscured by those who insist on links to ancient folklore. Determined to take the evidence with a generous pinch of salt, Juno navigates pagan ceremonies and astrological connections that turn up yet more bodies on a deadly path to the truth.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 426

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A Devon Midwinter Murder

STEPHANIE AUSTIN

For Claire

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

It was a lovely day for a murder, bright blue and sharp cold, the sort of December day I thought I’d never see again. Devon winters have been so mild and soft over the last few years. I suspected nothing. When I awoke, I had no sense of foreknowledge, no ominous fluttering of foreboding. Despite my recent experiences of discovering dead bodies, I have not yet developed an early warning system. Instead, I was excited, looking forward to the day.

It was Sunday so I had no dogs to walk, but I got up early and dressed in the dark, pulling on a thick jumper in readiness for the cold outside. Bill, curled up warm in a furry circle on my bed, didn’t even stir. I closed the door of the flat softly and tiptoed down the stairs, avoiding the treads that creaked. I didn’t want to disturb Adam and Kate on the ground floor, although their Sunday morning lie-ins are a thing of the past since baby Noah arrived.

I opened the front door and the cold snatched my breath. It was quiet, the little town of Ashburton still snug in its Sunday sleep, enfolded by the hills that rise up towards Dartmoor, undisturbed by the icy waters of the stream that burbles softly through its heart. The houses were in darkness, no lights showed; above their rooftops one laggard star remained that should have been in bed long ago. Not even the rooks roosting in the church tower had stirred their feathers yet. I rammed my woolly hat down over my hair and pulled on my gloves. The grass was crisp and crunched beneath my boots, ivy leaves sketched with chalk lines of frost. I love winter. Perhaps this Christmas, there would be snow, real snow.

I scraped a sparkling crust of ice from the windscreen of Van Blanc and headed for Old Nick’s. There was no one about in town. I passed the Victoria Inn, the stream sneaking behind an old weavers’ cottage, and drove through streets empty save for a solitary driver delivering Sunday papers to the co-op, stacking them in piles on the pavement by the door. I negotiated the cobbled ginnel of Shadow Lane, where my shop stands in splendid isolation – Old Nick’s: antiques, crafts, paintings and second-hand books – source of constant angst and not much income. Not so much cash flow as cash drip.

I unlocked the door, pushed it open, and for a moment stood in the dark and listened. Sometimes, when I go into the shop first thing, I get a sense of Old Nick still being around.

I don’t mean he’s a ghost. I don’t snatch glimpses of him from the corner of my eye, or hear the shuffle of his slippers on the stairs. He’s not a presence exactly. But as I walk in the door, I get a feeling as if I’ve come in on the end of his laughter, just missed it. And the joke is always on me. I had a perfectly viable business as a Domestic Goddess, cleaning, gardening and walking dogs, before Nick left me the antique shop in his will. Now I have to juggle two businesses just to make enough to keep this one running. But I remember his chuckle and his wicked blue eyes and realise that I miss him. Poor murdered Nick. I haven’t asked Sophie and Pat, who spend more time in the shop than I do, if they’ve experienced anything similar. Their imaginations are overactive as it is.

Boxes were packed and waiting inside, and I loaded them into my van, my breath puffing little clouds in the cold air at each trip; small antiques and collectibles for me, handicrafts and jewellery for Pat, paintings and display stands for Sophie. I locked them all in the back then headed up the hill towards Druid Lodge.

On the way I passed a number of posters tied to trees and telegraph poles, white rectangles in the thinning gloom, advertising today’s event and pointing the way. I didn’t need to read them because I’d helped to write them. Victorian Christmas Fair in aid of Honeysuckle Farm Animal Sanctuary, they announced proudly, Fun for all the Family.

That’s what today was about. Pat, who sells her handiwork in my shop, runs Honeysuckle Farm, a sanctuary for abandoned animals and injured wildlife, along with her sister and brother-in-law. It costs them a fortune to run and they are always desperately short of funds. Today’s event was about raising them some money, all profits going to support the animals.

I drove in through the gates of Druid Lodge and up the winding drive. As the house came into view, I could see there were lights on downstairs, so someone in that grand Georgian pile was up and about. Ricky and Morris are like vampires, they almost never sleep.

On the lawn stood two large marquees, ghostly white in the dimness, empty and waiting, like the animal pens in front of them, for their occupants to arrive. I’d parked Van Blanc and was still crunching my way across the gravel towards the house when the front door was flung open, revealing Ricky, tall and elegant in a silk dressing gown, one hand thrust into his pocket. ‘The breakfast shift’s arrived,’ he announced to no one in particular. ‘Hello, Princess! Watch these flagstones by the porch here, they might be a bit slippy. Bleedin’ hell, it’s cold!’

‘Well, get inside, then.’ I tugged the sleeve of his dressing gown as I entered the hall. ‘You’ll freeze in this thin thing.’

‘Noel Coward wore this, I’ll have you know,’ he sniffed as he shut out the cold behind me.

‘Onstage, maybe.’ I stamped my boots on the doormat and pulled off my gloves and hat. ‘I bet even Noel Coward had a fleecy one in real life.’

He cackled with laughter. ‘As to that, I couldn’t say. Come on in. Maurice is getting busy with a fry-up.’

I stuck my head into the kitchen. Morris threw me a glance, his bald head shining, his gold specs sliding down his nose as he jiggled sizzling pans on the Aga. ‘Hello, Juno love.’

The fair was not due to start for hours. I’d arrived in time for breakfast because, despite weeks of preparation, there were last-minute things to sort out. On our way through the hall, we passed rails hanging with Victorian clothes. Ricky and Morris have run a hire company for years, renting out costumes to theatrical groups, and their stock takes up most of the house. They’re always busy during the panto season, but a low demand for A Christmas Carol this year meant the Victorian department had enough left to provide costumes for today’s stallholders and volunteers. Ricky held up a full-skirted dress in a startling blue and green tartan. ‘We thought this would do for you.’

I gaped at it in horror. ‘You want me to spend all day in a crinoline?’

‘Now we agreed, Juno,’ Morris reminded me, calling from the kitchen, ‘all volunteers would wear Victorian costume.’

‘Can’t I get away with a mob cap and a shawl?’

Ricky raised an eyebrow. ‘Who do you think you are, some old washerwoman?’

‘Oh, do try it on, Juno,’ Morris pleaded, coming to the kitchen door and wiping his hands on his apron, ‘it will look gorgeous with your red hair.’

‘I’ll try it after breakfast,’ I said, praying it wouldn’t fit. But of course it would fit. Ricky and Morris know what’ll fit me, just by looking.

As I sat at the table, Ricky slipped his first fag of the day between his lips.

‘Not till after breakfast.’ Morris brandished a fish slice in his direction. ‘You promised.’

‘Oh, all right, Maurice.’ He sighed and put the cigarette away. ‘Tea or coffee?’ he asked me sulkily.

‘Coffee, thanks.’ I dragged my list of what we had left to do out from my shoulder bag and flattened it out on the table so we could study it over breakfast. It contained the names of all the traders and volunteers, stewards and raffle-ticket sellers. It may be the nerd in me, but I do love a list. I’d also sketched out a plan of the layout of pitches for people who would be setting up their own stalls outside in the grounds. Santa’s Grotto would be in the little wooded area next to the lake. The lights were already strung up in the trees, a job that had taken three days. Now they were just waiting to be switched on.

‘Have we got much left to do, Juno?’ Morris asked anxiously, as he placed a loaded breakfast plate in front of me. I crunched into a triangle of hot buttered toast. ‘We’ve got to put up those parking signs out in next door’s field,’ I muttered. Ricky rose to his feet as the doorbell rang. ‘Then let’s hope that’s another volunteer.’

It was two, as it happened. Olly charged into the kitchen, looking taller than when I’d seen him three days ago. But adolescent boys are like that, they grow in sudden spurts. He was taking off a cycling helmet, his little face pinched with cold, the tip of his nose and his sticky-out ears glowing scarlet. ‘Hello, Juno!’ he grinned.

‘You’re bright and early.’

‘Chris called for me at home and we rode up on our bikes,’ he answered, his eyes alight with excitement. ‘It was great, but it wasn’t half cold. I wish I had an e-bike like Chris.’ He sat down at the table and pinched a piece of toast. ‘I promised Pat I’ll give her a hand setting up the animal pens when she gets here.’ He began the construction of an elaborate triple-decker fried-egg sandwich, layered with brown sauce. ‘Aunt Lizzy’s coming later.’

Aunt Lizzy was my friend, Elizabeth.

Chris Brownlow strolled in then. The son of doctors whose house I clean once a week in my job as a Domestic Goddess, he was several years older than Olly and back from university for the holidays. He and Olly had appeared together in Ricky and Morris’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream back in the summer and were easy in one another’s company. ‘So, what do stewards have to do?’ he asked as he sat down.

‘Make sure people park their cars sensibly,’ Morris called out as he bustled back into the kitchen.

‘Yeh, and take money as people come in,’ Ricky went on, ‘then we need a few wandering about the grounds, pointing everyone in the direction of the loos, Santa’s Grotto, and just keeping an eye on people.’ He grinned, ‘Make sure no one falls in the lake.’

After breakfast I gave into pressure and tried on my costume. I stood in front of the mirror in the hall whilst Ricky raked fussy fingers through my curls. ‘Tried a comb this morning, have we?’ he asked waspishly, squashing a black velvet cap on my head and tying the long ribbons under my chin. I slapped his hands away, tried taking a few steps and felt the whalebone cage of the crinoline sway ominously. ‘I’m not sure I can move in this.’ I had visions of falling over and rolling down the slope of the lawn, caged in a tartan puffball, unable to stop myself and ending up in the lake.

‘You’ll get the hang of it.’ He handed me a pair of fingerless mittens. ‘And the long petticoats will keep you warm.’

So they might, but I was still keeping my leggings and boots on underneath. ‘I’ll put it on later,’ I told him as I began to wriggle out of the skirt. ‘I can’t shift stock in all this clobber.’ Through the window I could see the sky was lightening and glanced at the grandfather clock in the hall. Time to get going.

‘Yeh, buzz off,’ Ricky recommended.

I had to get my stall set out. I trudged back and forth from my van, carrying boxes of stuff that might loosely be described as ‘collectibles’ and dumped them on my trestle table. I put Sophie’s paintings and easels on the table next to mine. Like Pat, she works in my shop, manning it when I’m not there, in return for free working and selling space. Poor Sophie, she works so hard, but like a lot of talented people, her talent doesn’t translate itself into much cash. Pat would have her own stall, for her jewellery and handicrafts, as well as an information board about the work of Honeysuckle Farm, with photographs of all those animals patiently waiting for good homes.

Her old estate car was already bumping across the lawn, the back of it filled with creatures in cages. Pygmy goats, rabbits, guinea pigs, chickens and ducks would sit in pens on the lawn in a well-behaved fashion and form the petting zoo. With any luck, some of them would have found new homes by the end of the day.

‘Don’t forget you’ve got to get into costume,’ I reminded her.

She sniffed, her nose red with cold. ‘What’s the point of dressing me up?’ She rolled her watery blue eyes. ‘Well, if I feel chilly, I’m going to put my coat on over the top of it, whatever it is.’

As I walked back to the house to change, a petite figure came skipping towards me: Sophie, her short hair concealed by a bonnet, her dark eyes shining with excitement. She’d also appeared in the Shakespeare production back in the summer, was still a bit stage-struck, and had obviously decided changing into costume was a more important priority than getting her stall laid out. She wore a short velvet cape trimmed with fur, her blue dress revealing inches of lacy petticoat and pretty buttoned boots. I stared at the boots with envy. Why couldn’t I have some like that? The simple answer, I mused sadly, is they probably don’t make any large enough to fit a female who’s six feet tall.

‘Aren’t they lovely?’ she cooed, coquettishly pointing the toe of one foot to be admired.

‘Lovely,’ I agreed sourly as she danced towards the marquee. Ah well, the tartan crinoline awaits.

I saw a skinny figure in a patched tailcoat, his battered top hat set at a rakish angle, chatting to Pat’s sister Sue, who’d driven up from the farm in a horsebox: Olly, looking like the Artful Dodger. ‘School breaks up on Tuesday,’ I heard him telling her. ‘I’ll come up the farm on Wednesday and give you a hand.’

‘Volunteers always welcome, Olly,’ she told him. He loped over towards me. ‘Buy a raffle ticket from a poor boy, lady,’ he snivelled pathetically. ‘Only a pound a strip and we got some lovely prizes.’

We certainly had, and they were being kept safely on display in the tea tent. Lady Margaret Westershall had asked some of her well-heeled friends to donate prizes and she can be a formidable woman to say no to when the mood takes her.

There was a penny whistle sticking up from Olly’s pocket. ‘Aren’t you supposed to be playing carols?’ I asked.

‘Yeh, soon as the blokes on the squeeze box and fiddle arrive. They’re not here yet.’

‘Well, good luck.’ I looked at my watch. The fair was open to the public from twelve o’clock but our Local Celebrities, retired television stars Digby Jerkin and Amanda Waft, almost certainly wouldn’t turn up to cut the ribbon before the last minute.

I needed to get a move on, into the dreaded crinoline and back to my post. I didn’t anticipate selling much, or spending much of the day manning my stall. Elizabeth would watch it for me. Mine was more of a roving brief, keeping an eye on things. And it was my job to collect the stall money.

By now the sun was up, the sky was blue and except in the odd obstinate corner, the morning frost had melted away. I directed the Victorian Sweet Shop man to his pitch on the far side of the rose bed, his barrow packed with jars of humbugs, gobstoppers, sugar mice and anything else Victorian kids liked to rot their teeth with. Some of the food stalls had fired up, and the air was growing sweet with the smell of roasting chestnuts, hot spiced punch and minced pies. Christmas smells. I could see the tall, striped booth of the Punch and Judy man as he set up on the lawn. I was sure it was going to be a wonderful day. Which only goes to show, you can never tell what’s coming.

CHAPTER TWO

I was just getting the hang of the crinoline when Bob the Blacksmith turned up. His name isn’t really Bob, it’s Jeff; but Jeff the Blacksmith doesn’t have quite the same ring about it somehow. He’d named himself after a famous nineteenth-century boxer who packed such a powerful punch it was claimed he hid a horseshoe inside his boxing glove. Perhaps Jeff thought he could borrow some of his kudos. Whatever, he prefers to be called Bob. He works out of the back of a specially fitted van which includes a gas-fired forge, allowing him to ply his farrier’s trade around the farms and stables of Dartmoor. Back at his forge, he and his wife make fancy iron goods like weathervanes and sundials, and run courses for students.

Today, Bob arrived on foot, leading a black horse pulling an old-fashioned wagon. He had bought and restored a genuine American Civil War forge wagon, circa 1861, as he would proudly tell anyone who asked. His considerable bulk was squeezed into the dark blue uniform of a Yankee soldier. His uniform and wagon might fit perfectly into our Victorian theme, but the sight of them both made me shudder. I don’t like to think about horses going into war.

I gave him a wave as he approached and pointed across the grass to the pitch where I wanted him to set up his forge, on a stretch of flat lawn. It was a little way away from the rest of the fair, on the other side of the drive, but Bob had been the last trader to book a space for the day and it was the only pitch left that was big enough. At least he would be the first pitch people saw on their way into the grounds and the last on the way out.

His wagon was followed by a van packed with goods for sale. The driver, it turned out, was not another Yankee soldier as first appeared, but Bob’s wife Jackie, tendrils of black hair escaping from her soldier’s cap, a Celtic iron cross dangling from one ear. I wondered if she’d forged it herself. ‘D’you mind parking the van in the field next door once you’ve unloaded?’ I asked and she gave me a thumbs up. Bob brought his horse and wagon to a halt and wavered slightly, grinning at me inanely from the depths of his bushy black beard.

‘Is he all right?’ I muttered to Jackie. ‘He seems a bit … um …’

‘He’s been celebrating,’ she laughed softly. ‘It’s his birthday.’

‘He’s not drunk, is he?’ The thought of Bob drunk in charge of red-hot coals and sharp tools was not a comforting one, especially with members of the public about.

We watched him fumbling with the horse’s bridle and Jackie grinned. ‘Nah, he’ll be all right, you’ll see,’ she said, regarding him affectionately. ‘Good as gold, my Bob.’

I wasn’t sure I believed her, but I left them both to set up whilst I did a tour of the grounds, making sure traders arriving had all they needed. I almost didn’t recognise Pat, in a high-necked gown and shawl, hair demurely concealed under a mob cap. Morris had finished making breakfasts apparently, because he was now walking about dressed as Mr Pickwick.

‘Everything looks splendid, Juno, love.’ He drew a gold pocket watch from his waistcoat and consulted it. ‘All we need now is for the public to arrive.’

I glanced down the drive towards the gates where two stewards were waiting at a table to take the price of admission and realised what I’d forgotten. ‘I’ve got to give them their float and make sure the credit card machine is working.’ Admission to the fair might only be a pound, but you could bet some awkward bastard would want to pay by card.

‘You go down there and check on the machine, my love,’ Morris told me. ‘I’ll fetch the cash box. It’s locked up in the kitchen.’

As I hurried down the drive, trying not to trip over my crinoline, a camper van swept in through the gates and drew to a halt right next to me, crunching on the gravel and sending up a spray of tiny stones. ‘Sorry we’re late!’ Fizzy Izzy gave me a breathless smile as she stuck her head out of the window. She had a stall in the gift tent. The camper was being driven by her husband, Don.

I don’t like Don much. He and I got off to a bad start. Fizz used to rent space at Old Nick’s, and like me, she’s tall with red hair. There the resemblance ends, but it was enough to get her mistaken for me and she nearly got murdered as a consequence. Fizz bears me no grudge whatsoever, unlike her husband. Don’s resentment is understandable and I’m probably better off giving him a wide berth; but his hobby is woodturning, he produces fine work, and frankly, anyone who was prepared to cough up the fee for a stall today was welcome. Right now, though, he looked like thunder. He leant across Fizz from the driver’s seat and beckoned me close, glaring at me from fierce blue eyes, and jerked an aggressive thumb at where Bob was busy setting up his forge. ‘What’s that tosser doing here?’ he demanded.

‘Same as everyone else, I expect, here to sell his stuff. Why, is there a problem?’

‘I’ve worked a few craft fairs he’s been at,’ he said with something like snarl, ‘and he’s always trouble. I don’t like his attitude.’

I don’t like yours either, I thought, but I ignored the waves of rampant hostility emanating in my direction, gave what I hoped was a serene smile and pointed him in the direction of the gift tent. ‘You can drive up to the entrance to unload your stuff, and then if you don’t mind, could you park—’

I didn’t get to finish what I was saying. With a grinding of gears, the camper jerked forwards and off towards the tent, leaving me still pointing. Morris arrived at my elbow, puffing slightly, cash box in hand. ‘Everything all right?’ he asked.

‘Of course,’ I told him, although at that particular moment I couldn’t swear to it. I tucked my arm in his and we strolled down to the gate together.

Between us, the stewards and I worked out that the credit card-reader was functioning. Chris Brownlow jogged by in a brightly coloured steward’s coat, on his way to the car-parking field. He grinned at Morris. ‘Can I keep this coat, after?’

I peeled back a fingerless mitten to peer at my watch. ‘Aren’t Amanda and Digby here yet?’ There were only a few minutes to go before they were supposed to make their grand entrance.

‘It won’t matter,’ Morris confided. ‘They’ve already got their costumes. We sorted them out earlier in the week. Amanda wanted to choose hers herself.’

I laughed. ‘I bet.’

‘She’s a vision in pink,’ he added, giving me a sly nudge.

‘Well, let’s hope she’s sober. I’ve already got my doubts about Bob the Blacksmith.’

His brow wrinkled in an anxious frown. ‘Really?’

Ricky sauntered in our direction, dressed in a top hat and frock coat and twirling a silver-topped walking stick. ‘What’s up?’

‘Juno was just saying she thinks Bob might be drunk.’

‘Well, getting that way,’ I said. ‘It’s his birthday, apparently.’

Ricky’s eyes narrowed as he watched Bob staggering across the grass under the weight of an anvil, his mighty arms bent around it, clutching it close to his chest like a lover. He set it down on the ground with a grunt, then picked up a stone cider flagon and took a swig. ‘We’ll ask the stewards to keep an eye on him.’ He smiled suddenly, pointing his walking stick towards a knot of people heading up the drive from the gate. ‘Looks like our public is starting to arrive.’

It was another hour and a half before Digby and Amanda made their grand entrance, by which time, if the public wasn’t exactly pouring in, at least there was a steady trickle.

Amanda swept in like a galleon in full sail, in an enormous pink crinoline. She had twisted her hair into ringlets, her face framed by a bonnet with curling ostrich feathers, tied becomingly beneath the chin with a cluster of ribbons. As with everything she wore, this would have looked better on a younger woman. She seemed to be carrying a polar bear wrapped around one arm, but this turned out to be a large fur muff. With the other hand she clung to Digby, her faithful swain, looking handsome and distinguished in a frock coat and beaver hat with a curling brim. To what extent he was actually holding Amanda upright wasn’t apparent to the casual onlooker. But it was, I reminded myself cynically, still early in the day.

Morris watched as they made their way through a knot of clapping onlookers to a small platform especially set up for them. ‘That’s not our muff she’s carrying, is it?’ he asked.

‘I’ve never seen it before,’ I admitted.

Ricky grunted. ‘Must be her own, then.’

Digby, his fruity voice slightly disembodied by a microphone, was giving a speech about how honoured he and Amanda were at being asked to open the fair, reminding everyone it was for a very worthy cause, and encouraging them to spend generously.

‘Where’d they dig these two up from?’ a girl in front of me whispered. ‘Who are they?’

‘They used to be on the telly, years ago,’ her mother told her. ‘Some sit-com, it was. Pair of old has-beens, if you ask me.’

Whilst this assessment was undoubtedly accurate, it was also a bit unfair. Digby and Amanda still have lots of fans, although most of them live in retirement homes by now. And even today there is probably a TV channel somewhere endlessly running repeats of There’s Only Room for Two. I dared a glance at Ricky. He grinned at me and winked.

Amanda stepped forward, whipping a large pair of scissors from the confines of her muff, and with a little assistance from Digby, managed to cut the ribbon. ‘I declare this fair open,’ she announced graciously, ignoring the fact it had already been going strong for an hour and a half. ‘Please, all of you, have a wonderful day,’ she added, and threw the onlookers an airy kiss.

The three musicians struck up with ‘Deck the Halls with Boughs of Holly’ as Amanda handed the scissors to a waiting Digby and allowed Morris to lead them both over to the vendor of mulled wine for some much-needed refreshment. This would be the first stop on their tour of the fair. I decided I might tag along. That muff was worrying me.

CHAPTER THREE

I thought I’d better check in at the gift tent first. I hadn’t been inside since I’d set my stall up and was relying on Sophie, Elizabeth or fellow antiques dealer Vicky to cope if I had any customers. It was already getting busy. Half of the tent was occupied by a children’s workshop, a long table full of kids making Christmas decorations. Some of them were really getting into it, their clothes and hair smeared with glue and sparkling with glitter. A small gathering of people was listening to Pat talking about the animal sanctuary, and how the adoption scheme worked. ‘Adopt one of our animals today,’ she was telling them, in the slow deliberate voice of one who is trying to remember a script, ‘and for a small sum each month, you will receive photographs, regular updates and a VIP pass to the farm to visit your adopted pet whenever you like. And o’ course,’ she added, coming off script completely, ‘this makes a lovely Christmas present for the awkward bugger you don’t know what to buy for.’

I needn’t have worried about my stall. Elizabeth, Olly’s Aunt Lizzy, who helps out in Old Nick’s now and again, had already arrived. Vicky seemed to be explaining to her the finer points of the stock laid out on my table. I wished I had time to stop and listen. She knows far more about the stuff I’m selling than I do. Looking at the two of them together, I realised how alike they were: both in their sixties, slim, elegant and silver-haired. Although Vicky’s bobbed hair and long skirts were more relaxed in style than Elizabeth’s usually smartly tailored appearance. Today, though, they were both in crinolines – Vicky in purple with a wide collar and cameo brooch at her throat, Elizabeth in a silver-grey with deep lace cuffs. Neither of them had been saddled with tartan, I noticed.

‘You’ve just made your first sale of the day,’ Elizabeth informed me with a smile. ‘A little jug,’ she indicated its size between her palms. ‘Blue and brown.’

‘Torquay pottery,’ Vicky added with a twinkle. ‘Hello, Juno.’

I knew the jug they meant. Not exactly a big sale, but better than nothing. ‘Thank you, ladies,’ I said. ‘I’ll be back later. Keep up the good work.’

Ricky and Morris would be busy shepherding dignitaries and chatting up potential donors all day, so I’d been given the job of visiting each of the stalls to collect fees; but I decided I’d let everyone settle down and make some sales first. There was plenty of time. Besides, I was on a mission.

Amanda and Digby hadn’t made it into the gift tent; they were still outside. I needed to find them if I was to keep tabs on Amanda. I raised the edge of my crinoline to stop it dragging on the grass and hurried around a knot of families admiring the animals in the petting zoo, one little girl gently cuddling a duck in her arms. I glimpsed Amanda, her pink crinoline surrounding her, looking like a Barbie doll stuck in a blancmange. She was still attached to Digby’s arm, listening with politely feigned interest to Bob the Blacksmith. He had shed his jacket, tied on a leather apron, and was holding forth in a loud voice about his war wagon.

‘The coal box is at the back,’ he said, laying a hand upon it. ‘The bellows are inside the wagon and are pumped by this handle. The air is then piped through into the firebox at the front. Today, mind, I shall be using a furnace powered by bottled gas’ – he pointed to the forge he had set up, looking like an antique barbeque, a basket of glowing red coals balanced on a sturdy oak barrel – ‘for the simple reason it’s quicker to get going, and the missus doesn’t like having to pump these bellows all day long.’ He laughed and the crowd laughed with him. There was no denying that Bob was an entertaining speaker. There was also no denying that, at this particular moment, his speech was ever-so-slightly slurred. Jackie was watching him keenly, standing in front of display boards hanging with barbeque tools, pokers, key rings and medieval-looking pendants on leather thongs – all items which the public could buy, or have a go at forging for themselves. There were also daggers, swords and axe heads I hoped no one would want to have a go at.

Whilst Bob’s diction might be blurring around the edges, it didn’t stop his flow. ‘Now then, why do blacksmiths go to war?’ he asked. ‘To mend tools and weapons,’ he went on before anyone had a chance to answer, ‘but mostly because of these.’ He held up an iron horseshoe in his ham-like fist. ‘Horseshoes. And if any of you want, you can make a lucky horseshoe here today. Now, the horse doesn’t feel a thing when his new shoe is fitted,’ he went on, ‘but we would, if we grabbed one of these shoes when it was red-hot, wouldn’t we?’ He pulled a long, pointed chisel from his tool belt. ‘This ’ere is called a pritchel, ladies and gentlemen, and it has a very fine point’ – he demonstrated by touching it with a thick, sausage-like finger – ‘and this fits precisely into the holes on the horseshoe, allowing the blacksmith to carry the shoe from the forge and present it flat to the horse’s hoof …’

By now, Amanda had had enough of smithing and drifted away with Digby towards the gift tent, dutifully stopping to coo over the animals in their pens on the way. I stuck close behind her. Apart from Digby, I was probably the only person who knew Amanda had form. She’d once been arrested for shoplifting, and although that was many years ago, I knew her kleptomaniac tendencies hadn’t left her. She usually confined her light-fingered activities to the goods in my shop, but I was convinced the crowded tent with stalls crammed full of goodies would be too much temptation for her. I didn’t want anyone getting robbed, but equally, I didn’t want her getting caught. It would be a terrible humiliation for her and poor Digby, who suffered enough in my opinion, and would undoubtedly ruin the day. Also, I’d just glimpsed the burly figure of Detective Constable Dean Collins coming in the gate with his young family. He might be off duty, but if a crime was committed, he’d feel obliged to arrest the perpetrator. Worse, I’d seen Evie from the Dartmoor Gazette, her camera slung around her neck, here to cover the event for the local newspaper. I could just imagine the headlines if our Local Celebrities were Involved in a Nasty Occurrence. No, preventing crime before it happened was the only option as far as I was concerned. I was going to stick to Amanda like glue.

Unfortunately, I got stopped on my way into the tent by the arrival of Lady Margaret Westershall and her two bulldogs, Florence and Wesley. It wasn’t so much her bearing down on me with a loud hail of ‘Juno, my dear!’ that impeded my movement, as an excited Wesley diving under my crinoline and nearly knocking me off my feet. Lady Margaret had been generous, not only in contributing funds for the fair, but in cajoling her contacts in various charitable organisations to provide lavish raffle prizes. I disentangled Wesley from my petticoats as I thanked her for all she’d done.

‘Nonsense, the least I can do,’ she responded briskly.

‘The raffle prizes are superb,’ I told her. ‘We’re selling lots of tickets.’

‘Excellent.’ She patted my arm. ‘You look like a cat on hot bricks, my dear. I expect you’ve got loads to do. You carry on. Wesley, Florence and I are going into the tea tent for a spot of lunch. See you later.’

I didn’t wait around to watch her go but plunged into the marquee. Digby and Amanda were standing by a stall selling handmade soaps and candles. Then, to my horror, I saw them stop at Don Drummond’s table. Please, please, I prayed silently, do not try to steal anything from Don Drummond. He had beechwood platters and ash bowls on his table, too large to be picked up without notice, but I could also see bowls of wooden light-pulls and turned drawer knobs, and other items small enough to delight the pilfering finger. I tried to edge closer, but the tent was full by now, and squeezing through a crowd whilst wearing a tent of your own is not an easy matter. Muttering apologies, I forced my crinoline between members of the public. Amanda was as light-fingered and skilled as any Victorian pickpocket; I’d seen her at work before and knew what to look for. I saw that familiar movement, a quick whisk of her fingers and something disappeared inside her capacious muff.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t the only one to spot the movement. Eagle-eyed Don Drummond had noticed it too. ‘What did you do just then?’ he demanded, glaring at Amanda.

She blinked at him like a startled owl. ‘I beg your pardon?’

‘You did something,’ he insisted. ‘Put something in that muff.’

‘I’m afraid I don’t know what you’re talking about,’ she responded, her free hand fluttering nervously for a moment at her breast.

‘I want to see what’s inside.’ He held out a hand, waggling his fingers as if he expected her to hand it over.

But Amanda was not an actress for nothing. She drew herself up to her full height and gave him her best haughty stare. She does a very good one, looks at people as if she’d only handle them with tongs. ‘I don’t know what you’re implying,’ she said.

‘You know damn well what I’m implying.’

All around them the tent was falling silent. There was only one thing to do, and I had to do it fast. I trod on the hem of my crinoline and pretended to stumble, launching myself forward and reaching out with both arms to save myself. One hand caught at the edge of Don Drummond’s table. I grabbed at the cloth covering it and pulled, dragging the bowls of small objects forward, upsetting them and tipping them over the edge. A cascade of small wooden knobs spilt everywhere. With my other hand I grabbed at Amanda’s muff and managed to drag it from her sleeve before collapsing on the ground in a mushrooming cloud of tartan crinoline. ‘Oh dear!’ I cried out loudly as I fell. ‘Oh, I’m so sorry!’ I slid my hand into the muff’s silk lining and my fingers closed on three small objects. One felt like a wooden drawer knob. I closed my fingers tightly around the rest and clutched them in my hand as Ricky, eyes narrowed in suspicion, stooped to help me up. Digby, meanwhile, was fussing around Amanda. ‘I’m so sorry Amanda,’ I exclaimed as I was hauled to my feet. ‘I didn’t hurt you, did I?’

‘No, of course not,’ she answered coolly.

‘Don, was there some sort of problem?’ I asked innocently. I held out the muff. ‘Did you want to see this?’

Without a word he snatched it from me and plunged his hand inside. His fingers finding nothing, he glowered at me and then thrust the muff back at Amanda. He said nothing but I could see a pulse of anger beating in his cheek. He’s not the sort of man to like being made a fool of. Sophie, being a helpful sort, had hurried out from behind her table and begun picking up the fallen drawer knobs. She placed a handful on the cloth I had so clumsily disarranged and began to smooth it out. ‘There,’ she said innocently.

‘Are you all right, Mandy?’ Digby asked solicitously. ‘And you, Juno, you didn’t hurt yourself?’

‘Only my dignity,’ I assured him. ‘Why don’t you and Amanda go and visit the tea tent?’ And for God’s sake keep her away from the raffle prizes, I added privately.

‘Good idea!’ he agreed as Amanda slid the muff back on to her arm. He turned to Don. ‘No damage done is there, old chap?’ he asked. ‘Nothing broken?’

‘No,’ Don answered between gritted teeth. ‘Nothing broken.’

‘What the hell was all that about?’ Ricky muttered as Amanda and Digby glided away.

‘Just me tripping over this damn crinoline you’ve made me wear.’

Ricky’s not easily fooled. He eyed me for a moment, clearly disbelieving, but decided to let it go, shook his head and walked on. I turned away and slyly opened my fingers to take a look at the tiny objects digging into my palm: a silver spoon, which I knew belonged to a mustard pot on Vicky’s table, an old WWI service medal and a wooden drawer knob. What on earth could Amanda want with this odd assortment? Nothing, was the answer. She was driven by the compulsion to steal. It seemed it didn’t matter what.

‘Sorry,’ I said, returning the spoon to Vicky. ‘I must have knocked this off your table when I fell.’ This clearly could not have been possible, but she made no comment, receiving the spoon with thanks and a bemused smile. I dropped the old WWI medal back on my own table, where it had come from. Elizabeth gave me a quizzical look but said nothing.

‘Oh look!’ I cried, bending down and pretending to pick something up from the ground. ‘it’s one of your drawer knobs, Don.’ I placed the one I’d palmed from the muff down on his table with a smile. He didn’t say anything either. Not even thank you.

The rest of the afternoon passed without incident, plenty of visitors arriving and tucking into the various eats on sale or making their way to the tea tent. By the middle of the afternoon the gift tent was heaving, with good sales reported by everyone inside. At the petting zoo, several guinea pigs had been earmarked for rehoming, Sue informed me happily, once they had been coaxed out of hiding under their straw.

I saw Dean Collin’s eldest child, my little god-daughter Alice, her chubby legs astride the saddle of Maureen the donkey, shrieking with delight as the animal plodded along, Sue leading her, her father walking alongside holding her firmly in place on the saddle. Her baby sister, born on Hallowe’en, was wrapped up in a sling on her mother’s chest, snug as a pea in a pod, only the fuzzy bobble of her hat visible to the naked eye. I waved to them, but didn’t stop. I was clutching my clipboard with the list of stallholders, a bag of change and a receipt book, ready to take their money. It would take a while to get around all of them and I thought I’d start with Bob the Blacksmith, whilst he was still sober.

He was still on his feet, anyway, intently watching as a customer in leather gauntlets, his face half hidden by protective goggles, was striking at a piece of red-hot metal on the anvil, sending up glowing sparks. ‘That’s my dad,’ a child in the crowd of onlookers pointed proudly.

‘What’s he making?’ I asked.

‘A sausage sizzler, for the barbecue.’

Bob felt it necessary to take over from dad at this point, hammered the metal with far more forceful blows and then returned it to the red-hot coals of the forge using tongs. He staggered slightly as he stepped back, bending to pick up his stone flagon from the grass and taking a lengthy swig. ‘Thirsty work,’ he nodded to the crowd as he wiped a hand across his mouth. There was a ripple of slightly uncomfortable laughter. After a few moments he withdrew the irons from the brazier, put them back on the anvil and handed the tongs to the customer. ‘Give the end another bashing,’ he recommended.

Satisfied Bob was still under Jackie’s watchful eye, I collected the pitch money from her, wrote out a business receipt, then trailed my horrible crinoline back over the grass towards the food stalls. It seemed like a long time since breakfast and I was feeling peckish. A mince pie would go down nicely. I bumped into Ricky, apparently on his way to the loo. He grabbed my arm. ‘Mandy up to her old tricks again?’ he murmured, ‘in the gift tent?’

I blinked at him for a moment. ‘I didn’t think you knew.’

‘Oh, come on! Every time she and Digby come to the house another ornament goes missing.’

‘Have you ever said anything?’

‘Nah! Not worth it. Poor old Diggers, we wouldn’t want to upset him. His life must be a nightmare as it is.’ He tapped his hat in a mock salute as he hurried away. ‘Must go,’ he said. ‘Carry on.’

As the afternoon sun was sinking lower, the air was turning chilly. I arrived at Neil and Carol’s cider stall. They owned orchards at their farm near Widecombe. Dressed in old-fashioned farmers’ smocks, breeches and floppy hats, their gloved hands were wrapped around styrofoam cups of steaming coffee.

‘You will come to our wassail in January, won’t you?’ Carol asked. ‘We’re blessing the orchards, although,’ she added with an uncertain smile, ‘it is a pagan ritual, so I’m not sure if blessing is the right word.’

‘It’s just a laugh,’ Neil told me, ‘an excuse for drinking and dressing up.’

‘Well, I’m all for that,’ I said. ‘I’d love to come.’ I noticed some stone flagons on their stall. ‘Did you sell one of those to Bob the Blacksmith earlier?’

He grinned. ‘He was our first customer of the day. He hasn’t started drinking it already, has he?’

‘Afraid so. It’s his birthday, apparently. Mind you, I think he’d already had a few before he left home.’

Neil laughed and shook his head. ‘He’s an idiot. Trouble is, he can get bolshy when he’s drunk. He got into a fight with a fella at an agricultural fair back in the summer.’

‘A fight? You mean proper fisticuffs?’

‘Me and a few other guys had to pull them apart.’ He nodded his head in the direction of the gift tent. ‘He’s in there, the bloke he fought with, I saw him when I went in for a look around.’

‘Let me guess, Don Drummond?’

‘The woodturner?’

‘That’s the fella!’ I nodded. ‘What were they fighting about?’

‘God knows! Never found out, but they each blamed the other one for starting it.’

‘Men!’ Carol tutted, laughing. ‘They’re all the same.’

This earned her an astonished look from her husband. ‘Excuse me?’

I decided it was time to leave them to their coffee and headed for the man with the barrow of Victorian sweets. I’d like to have known more about Bob and Don’s fight, though. From my very slight knowledge, I’d have said Don was the more aggressive of the two, more likely to start a fight, and Bob, the stronger one, more likely to finish it.

As the darkness of a winter afternoon closed in, the sky fading from blue to indigo, will-o-the-wisp lights twinkled in the wood and sparkled on the black water of the lake. At exactly four o’clock Father Christmas arrived on the cart drawn by Nosbert the steadfast carthorse, driven by Pat’s brother-in-law, Ken, the bells on the harness jingling festively.

I wouldn’t have recognised Morris. Apart from a magnificent scarlet robe and false beard, a wig of luxuriant silver curls covered his bald head and a Christmas crown, a wreath of holly and mistletoe twined with ivy, was set upon his brow. Waving and ho-ho-ho-ing, he rode down to his grotto, followed by a gaggle of excited children dragging their parents. At around the same time, Digby’s voice came over the sound system, asking all those visiting Father Christmas in his grotto to stick to the lantern-lit path, as the garden was steep in places and we didn’t want any accidents in the dark. He also announced that he and Amanda would shortly draw the raffle tickets and winners could collect their prizes from the tea tent. And finally, anyone who fancied a good old Christmas sing-song, please go down to the lake where a carol concert would be starting shortly, under the baton of Professor Jingle.

Professor Jingle, otherwise known as Ricky, would be conducting from the keyboard of an ancient upright piano, which had been rolled out from somewhere, accompanied by the three roving musicians on accordion and fiddle, Olly swopping the penny whistle for his bassoon.

I wanted to go down and join in, but I still had money to collect.

The gift tent looked deserted now, most of the children dumping their Christmas decorations in favour of the trip to Santa. But the traders had taken enough money to keep them in festive spirit. Even Don had a smile on his face. He’d taken a commission from Neil and Carol apparently, who’d asked him to turn a special wooden drinking bowl for their wassail in January. The ladies of the antiques team, Elizabeth and Vicky, had deserted their posts and gone to the tea tent along with Sophie, leaving Vicky’s husband Tom to man the stalls single-handedly.

After I’d finished taking stall money, I headed back to the house. I had Morris’s spare back-door key hidden inside my mitten, ready to let myself in. Pat hurried after me so she could come in and change out of her costume. The residents of the petting zoo were caged up and she wanted to take them back to warmer quarters at the farm. ‘We can’t leave ’em out here now night’s fallen. Thanks ever so much for organising all this, Juno,’ she added. ‘It’s been wonderful.’

‘It’s Ricky and Morris you need to thank, I just had the idea.’

‘I know, but it still wouldn’t have happened without you.’

‘It’s not over yet.’ The money from admission and raffle tickets would be going to the farm too. We were looking forward to counting up all the takings later.

‘I’ll come back here as soon as I’ve settled the animals down.’ Pat hung up her dress and shrugged herself back into her old jacket. ‘And I’ll pack up my stall. Thanks for bringing my stuff from the shop this morning.’

‘You had the animals to think about and I had to fetch mine and Soph’s anyway.’

I followed her out of the house, locking the door behind me. As I came around to the front, I almost collided with one of the stewards holding a lantern. ‘I don’t think anyone else will be coming in through the gate now,’ he said, ‘so there’s not much point hanging around.’

He was right. The public were already beginning to drift away and I knew the stallholders would start packing up soon. He handed me the cash box and credit card-reader. ‘We’ve had a fair few in, though.’ He rubbed his hands together. ‘I’m going to catch a cuppa in that tea tent before I go home.’

I returned a pleasingly heavy cash box to the kitchen. It seemed the card-reader hadn’t been needed much. Whilst I was inside the house, I changed back into my own clothes. There was really no point in staying in the stupid crinoline any longer. I wriggled out of it and hung it up, glad to see the back of it.

It was fully dark by now. A string of lanterns cast their light on the path leading down to the grotto. Families were still queuing to see Santa. At the back of the queue, I could make out the distant but unmistakeable figure of Dean Collins, carrying little Alice.