7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Devon Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

Returning from a brief holiday, Juno Browne is relieved to find that no one has been murdered in the picturesque Dartmoor town of Ashburton while she was away. Though uncharitable friends suggest that the quiet was simply due to her absence. Just as she's settling back into her routine at the antiques shop and as domestic helper and dog walker, the brutal killing of local journalist Sandy Thomas shocks the town and Juno is swept up into a fresh murder inquiry. What was Sandy really investigating on the night she was killed? With a spate of dog kidnappings to contend with as well, the Devon countryside never felt less tranquil, and inevitably Juno's amateur sleuthing skills will be called upon once again .

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 418

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

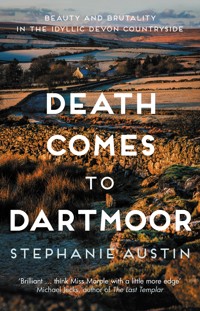

Death Comes to Dartmoor

STEPHANIE AUSTIN

To Katy and Phil

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

I left Ashburton at the fag-end of a long, hot summer. There were no murders in my absence. During the ten days I was away there were certainly some interesting goings-on, but no suspicious deaths. According to some of my more uncharitable friends, this was simply because I wasn’t there. It was even suggested that it might be safer for the residents of Ashburton if I stayed away permanently. I think this is unkind. It’s not my fault I’m good at finding dead bodies. And, as it turned out, whatever strange power arranges these things, was merely saving them up until I got home.

When you run two businesses, even taking a short holiday is not an easy thing to contrive. I had to time it carefully. The shop wasn’t a problem. Sophie and Pat have looked after Old Nick’s on a daily basis ever since it opened, and with the tourist season tailing off at the start of the new autumn term, it was unlikely that a shop selling art, crafts, antiques and second-hand books was going to be overwhelmed with business. In fact, our takings were so dismal whilst I was away it wouldn’t have mattered if we’d hung the closed sign on the door.

It was the other half of the business – the domestic goddess half – which was the problem. I walk five dogs on weekdays, as well as clean for, and generally help out, a variety of human clients. It was making sure their needs would be taken care of whilst I was away that was the difficult bit. But I hadn’t seen my cousin Brian for over two years, and I needed a break. He’s my only remaining relative, my mother’s cousin, which makes him either my second cousin, or first-cousin-once-removed, I’m not quite sure. He’s always been more like an uncle to me, older, wiser, chummy and kind. He’d recently come home on leave before taking up his new diplomatic posting, so I popped up to London to see him, spending ten days in his flat. He was off down to Portsmouth for a week’s sailing after that. He wanted me to go too, but I get sea-sick and anyway, there is only so much of Brian’s hag-wife, the toxic stick-insect Marcia, that I can stand. I promised to visit him again later, once he’d taken up residence in Paris.

As it happened, things worked in my favour. My most ancient client Maisie, ninety-six and still counting, was to receive a visit from her daughter, Our Janet, down from the wilds of Heck-as-Like, or wherever she lives up north, so I was able to organise my holiday at the same time. I managed to subcontract the dog walking to Becky, who runs a mobile dog-grooming business. Mrs Berkeley-Smythe was away on a cruise and wouldn’t need my services till she got back, and I knew my friend Elizabeth would keep an eye on Tom Carter. Everyone else, as far as I was concerned, could manage without me.

I haunted the markets of London, lusting after antiques I couldn’t afford to buy for Old Nick’s. I was determined to keep my money in my pocket, despite Brian’s assurance that anything I bought could easily be buzzed down to Devon by carrier, no trouble at all. I went shopping with Marcia, resisting her attempts to drag me to the gym each morning, and we bonded, slightly. We don’t really like each other, but for Brian’s sake we did our best to get along. Why, after fifty years of contented bachelorhood, he had decided to marry a widow with two grown-up daughters, I don’t know. To be fair, Marcia is probably an ideal wife for a diplomat. She’s fluent in three languages, can organise a formal dinner party at the drop of a hat and apparently plays a fiendish hand of bridge.

At first, I felt energised by the buzz of London, the rush, but the excitement quickly wore off. I found myself longing for muddy lanes and birdsong. At the end of ten days when every day had been crammed with shopping and sightseeing, each evening spent at an expensive restaurant or a West End show, I was more than ready to come home. As my train headed back into Devon, I found myself letting out a breath.

From Exeter the railway line hugs the south Devon coast, passing red cliffs on one side and the open sea on the other. The train stops at Dawlish, where on wild nights sea spray washes over the carriages. During a storm a few years back, the rocks beneath the line were swept away, leaving the track swinging like a rope bridge a few feet above the churning waves. The track turns inland after Teignmouth, running alongside the lazy grey waters of the Teign estuary to Newton Abbot, which is where I got off.

Despite my determination not to shop, I’d come back from London with far more bags and baggage than I’d left with. I’d received several offers from people happy to pick me up from the station but decided I’d rather sneak back into Ashburton with the minimum of fuss. On the other hand, I didn’t fancy the bus ride with all my baggage, so I compromised and took a taxi. My last little luxury, I warned myself, before I got home. The previous occupant had left a copy of the Dartmoor Gazette on the back seat, and I gave it a quick flick through to see if anything interesting had been happening whilst I’d been away.

Not much. Someone living in the village of Scorriton had lost her Labradoodle, convinced it had been stolen, and police were searching for three men who’d been spotted climbing out of the back of a lorry just disembarked from the ferry at Plymouth. Then, buried at the foot of an inside page, I found something fascinating.

District councillor and property developer, Alastair Dunston, was granted a restraining order against a member of this newspaper’s staff at a court hearing in Exeter today. The injunction bars our reporter, Sandy Thomas, from being within one hundred yards of Mr Dunston’s home. Mr Dunston was quoted as saying that Ms Thomas had exceeded the considerable liberties afforded to members of her profession, stalking him and harassing members of his family. Ms Thomas was also accused of causing an affray at a fundraising dinner attended by Mr Dunston and was bound over to keep the peace.

What had Sandy been up to? She can be a pestilential nuisance, as I knew to my cost, forever pestering me with questions when I’d accidentally got myself involved in a murder investigation. It was she who saddled me with the title of ‘Ashburton’s Amateur Sleuth’, a source of cringing embarrassment to me ever since. Merely the sound of her breathy, Welsh voice on the phone was enough to wind me up. But she was just doing her job. She could be pushy, but I couldn’t imagine her making so much of a nuisance of herself that someone had taken her to court. And what had Alastair Dunston been up to that had aroused so much of her interest? I squinted at his photograph. He was quite good-looking. County councillor and property developer, that was a likely conflict of interest for a start. But causing an affray, what was that all about? I noticed that the newspaper hadn’t offered any comment on her activities. Poor old Sandy. At least they hadn’t given her the boot.

By now the taxi had pulled up outside of my house, forcing me to abandon the newspaper. I had to get out and pay the driver, who retrieved my suitcase from the back but drew the line at carting my baggage up the steps to the front door. I watched him turn his vehicle around at the end of the lane, then gathered up my chattels and began the ascent.

I was happy to be home. O, Little Town of Ashburton, how still we see thee lie, straight off the slip road from the A38, wedged between the dual carriageway and the Dartmoor foothills. It doesn’t have the biscuit-tin prettiness of some Dartmoor villages, no duckpond or thatched cottages. It’s an old stannary town, where for centuries tin mined on the moor was assayed and stamped. Shops catering for tourists may have replaced its ancient trades, but it’s quirky, with lanes and passages the tourist can easily miss, the ruins of history buried in its stone walls, with green hills rising up behind it and a little river sliding sneakily through its heart. I love it. I never want to live anywhere else.

I’d worried about Kate whilst I was away. I rent the top floor of the house she occupies with Adam. They’re expecting their first baby in a few weeks and she’s been having a rotten pregnancy, her daily sickness not confining itself to mornings, and with no sign of her nausea abating as the birth approaches.

I dumped my baggage at the foot of the stairs, pausing to extract a parcel from one of my shopping bags, and headed for Kate’s kitchen door. She answered my knock, grinning as we hugged. She looked beautiful as ever, but heavy-eyed, as if she wasn’t getting enough sleep.

‘How was the trip?’ she asked, and added mischievously, ‘How was Marcia?’

‘We managed not to come to blows,’ I admitted, ‘although she doesn’t approve of me at all.’ I had, in her words, wasted the expensive education that Brian had paid for by setting myself up as some sort of paid dogsbody and not pursuing a proper career. Becoming the owner of what she referred to as a junk shop had done little to raise my status in her eyes. ‘Anyway, never mind me, how are you?’

‘I’m not throwing up so much,’ she admitted, eagerly unwrapping the gift I had brought her. She held up the spotted Babygro. ‘Aw … thanks! But this one,’ she added, stroking her beachball tummy, ‘keeps me awake most nights, kicking.’

‘How’s Adam managing at the cafe?’

‘Chris Brownlow is still helping out. He doesn’t go back to college until next month.’

Chris was the son of one of my clients and had taken on working at Sunflowers as a holiday job.

‘Cup of tea?’ she asked. ‘Piece of cake?’

Frankly, I was ravenous. Breakfast at Brian’s seemed like a long time ago, but I knew I’d emptied my fridge before I went away and I’d better go shopping. Besides, I wanted to call in on Old Nick’s before closing time. ‘Not just now, thanks.’ I squeezed Kate’s arm. ‘Catch you later.’

As I dumped my bags on the sofa upstairs, I could see the red light of my ancient answerphone flashing. For a moment I thought it might be a call from Daniel. But it wouldn’t be. With a sinking feeling inside, I remembered it would never be a call from Daniel again.

I pressed the play button and a loud, slightly raucous voice demanded to know what I’d been up to in the big city. It was Ricky. ‘Give us a call when you get back,’ he urged, so I settled myself down on the sofa, kicking off my shoes and putting my feet up on the coffee table. The shopping could wait. Within moments, Bill appeared from my bedroom, leapt onto my lap and began an enthusiastic greeting procedure, treading my midriff with his paws and purring like a Geiger-counter, whilst simultaneously headbutting the hand that was holding the phone. He must have missed me. He’d probably been living in my flat the entire time I’d been away, going downstairs only for meals. I smoothed his black head and told him how gorgeous he was.

‘Druid Lodge Theatrical Hire,’ came a slightly weary voice at the end of the phone.

‘Ricky, it’s me.’

‘Princess, where are you? At the station?’

‘No, I got a taxi home.’ I ignored his tutting. ‘There was one waiting at the station entrance,’ I lied, ‘I thought I might as well get in it.’

‘Expensive journey home,’ he sniffed.

Yes, it had been.

‘You know we’d have picked you up.’

‘Well, I’m here now.’

‘So come on up! Maurice and I would love to see you. You can tell us all about what you got up to in London. D’you see any shows?’

Ricky and Morris are two of my oldest friends and I love ’em dearly, but actually, I’d been fancying a quiet night in. Then I remembered something. ‘Do you know anything about this business with Sandy Thomas? The paper said she’d been accused of causing an affray. Something to do with some councillor?’

‘You mean Alastair Dunston.’

I knew I could rely on Ricky. ‘You know about it?’

‘Know about it?’ He cracked with laughter. ‘Darlin’, we were there! It was a fundraising bash for the air-ambulance.’

‘When was this?’

‘A few weeks back.’

I frowned. How come I hadn’t heard about this until now? ‘Where was I?’

‘Oh, Gawd knows! Up to no-bleeding-good, I expect. Look, why don’t you come up to the house, let us cook you supper? You can hear all about it and tell us about your trip.’

‘Deal,’ I agreed without hesitation and disconnected. I glanced at my watch and then at Bill, who’d settled down on my lap, purring, his paws tucked under, his one emerald eye closed in contentment. Anyone would think he was my cat. ‘Sorry,’ I told him, lifting him off my lap. ‘But I want to get to the shop before it closes. I’m going to have to get going.’

Sophie and Pat man Old Nick’s for me in return for the rent-free space they occupy. They have done so since I unexpectedly inherited the shop from a former client, Mr Nickolai, after he just as unexpectedly got himself murdered. It’s an arrangement that works well. Neither of them can afford to pay rent. Sophie doesn’t sell enough pictures and all Pat’s money goes on running a sanctuary for abandoned animals with her sister and brother-in-law. But their being in the shop gives me time to pursue my domestic goddess business, the one that actually earns me some money. Most days, they take it in turns. But that afternoon they were both in the shop, Sophie’s dark head bent over a watercolour she was painting and Pat frowning over some jewellery on her worktable. Elizabeth was there too, arranging books on the shelves in alphabetical order. She comes in to offer a hand now and then. As always, she looked cool and elegant in a spotless white blouse, her silvery-blonde hair swept up into an elegant chignon, and made the rest of us look scruffy.

‘Nice to see the place is still standing,’ I announced as I walked in. ‘Hello!’

‘That’s about all it is,’ Sophie complained. ‘The till’s hardly rung all week.’

‘It hasn’t been quite that bad,’ Elizabeth corrected her with a smile. ‘The book exchange is starting to work well.’

‘At least it brings people in through the door,’ Pat agreed, without looking up from what she was doing. ‘Hello, Juno.’

I passed her a bag of some unusual beads I’d picked up from a specialist shop in Covent Garden. I’d bought big, soft paintbrushes for Soph and an Edwardian hair-slide for Elizabeth. They all went through the you-shouldn’t-have-but-I’m-glad-you-did routine and after recounting my adventures in London I had a brief and rather depressing look at the sales ledger.

Sophie tickled the palm of her hand experimentally with a new paintbrush. ‘At least Christmas is coming.’

I shuddered. ‘It’s only October.’

‘Now you’re a shopkeeper, Juno, you’ve got to start thinking of these things early.’ Pat held up what looked like a pumpkin earring. ‘I’m making these for Hallowe’en.’

‘Exactly, I’ve got you and Soph to think about these things. It doesn’t make any difference to me. Antiques are the same whatever time of year it is.’ I had to admit that in the run-up to last Christmas they’d made the shop look fabulous. If only Old Nick’s was on North Street or East Street, instead of stuck down narrow and dingy Shadow Lane, it might have made a difference.

‘These things take time to build,’ Elizabeth observed. ‘There’s no point in getting despondent.’

‘No. Grit and determination is what it takes.’ I thumped the counter with my fist in mock resolution and announced I was going to the loo.

Nick’s old bathroom is on a landing halfway up the stairs, part of the old flat above the shop and, together with his kitchen, comprised the staff facilities. I was just about to come out again, having done what I needed, when I heard Sophie say, ‘Are we going to tell her?’

‘Let sleeping dogs lie, that’s what I say,’ Pat responded. ‘Juno’s going to find out about it soon enough. Why upset her before we have to?’ I pulled the bathroom door to softly and listened.

Sophie sounded angry. ‘What the hell’s he done it for?’

‘He needs a proper phone signal and broadband to be able to work.’ This was Elizabeth’s voice. ‘He’s got nothing up at that farmhouse.’ They were talking about Daniel, my all too briefly loved-and-lost lover. He’d inherited a farmhouse up on Halsanger Common, a few miles out of town. Practically a ruin, it lacked even the most basic of facilities and he was living in a caravan whilst it was being rebuilt. ‘I don’t suppose he’s renting an office just for fun.’ Elizabeth retained some contact with Daniel through the doctor’s surgery where she worked as a part-time receptionist and where he was a patient.

‘But does he have to rent one around the corner?’ Sophie demanded. ‘So near to here?’

‘I imagine finance has something to do with it and there probably wasn’t a lot of choice.’

‘You don’t think he’s done it deliberate, like?’ Pat asked. ‘To be near Juno?’

‘In order to torment himself, you mean?’ Elizabeth asked mildly.

‘He’s the one who broke it off,’ Sophie objected. ‘He can torment himself all he likes, but I don’t want him tormenting Juno.’

Pat grunted. ‘I don’t know why he broke it off in any case. I know she gets up to some daft things, damn dangerous some of ’em, but what’s the point in worrying?’

‘Don’t forget he lost his first wife in tragic circumstances.’

‘Well, I know,’ Pat conceded, ‘and that’s all very sad. But, be honest, any one of us could get killed any day, just crossing the street.’

Elizabeth gave a soft laugh. ‘True, but Juno does have a tendency to throw herself into the traffic.’

‘You sound as if you’re defending him,’ Sophie accused her.

‘I think I understand why he broke with Juno,’ she responded calmly, ‘but I still think he’s wrong.’

I decided it was time to stop lurking on the landing and came down into the shop.

‘So where is it, then?’ I asked as the three of them turned to look at me. ‘This office that Daniel has rented?’

Sophie threw Pat an agonised glance.

‘It’s around the corner on East Street,’ Elizabeth responded before either of them could speak, ‘above the beauty therapist.’

‘At least he won’t have to go far to get his nails done.’

No one laughed. Sophie’s eyes glistened dangerously. ‘Don’t look so tragic,’ I told her. ‘It’s all right. Really.’ I smiled but couldn’t contain the sigh escaping from my chest. ‘I can’t control what he does so …’ I shrugged, ‘it makes no difference to me.’

This was a lie. During our short relationship, Daniel had worked away a lot, so I was used to long periods of not having him around. And if he stayed up in his lonely caravan, out of my way, perhaps I would stand some chance of forgetting him. But if he was renting an office in town, we were almost certain to run into each other. And that would be a different thing altogether. Suddenly, I wished I’d gone sailing with Brian after all.

CHAPTER TWO

Ricky and Morris’s place is practically my second home. An imposing Georgian residence set in lovely grounds it sits high on a hill overlooking Ashburton. I’ve stayed there a lot. As well as being home to Ricky and Morris, it houses several thousand theatrical costumes, which they hire to groups all over the country. During the time I’d been away, Oklahoma! had been returned, and they’d sent out Half a Sixpence. The leaves might be only just on the turn, but they were already gearing themselves up for the pantomime season. I try to help them out with the packing and unpacking when I can, but these days, I don’t have much spare time.

‘So, what’s all this about Sandy Thomas?’ I’d kept them entertained, telling them about the shows I’d seen in London during the creamy fish pie and minted peas. Now that we’d arrived at the plum crumble, I reckoned it was their turn.

‘Well, there’s not a great deal to tell,’ Ricky admitted, making me feel he’d got me there under false pretences.

Morris shook his bald head. ‘It was all over very quickly. I don’t think anyone realised what was going on.’

Ricky grinned. ‘Not until the champagne started flying.’

‘Can we start at the beginning?’ I asked. ‘What was Sandy doing there? Was she covering the event for the paper?’

He shrugged his shoulders. ‘S’pose.’

‘It was quite early on in the evening,’ Morris explained. ‘People were still arriving. Everyone was just standing around in the ballroom, glasses in hand …’

‘Mingling,’ Ricky interrupted, putting a cigarette to his lips.

‘The waiters were bringing trays of canapés round, then there was the sound of breaking glass,’ Morris went on. ‘One of the waiters had dropped a tray.’

‘He’d got in the way of Sandy, waving her arms about.’ Ricky drew on his fag, leaning back in his chair, draping one long arm over the back. ‘She looked a bit rough, to be honest.’

Morris frowned. ‘I don’t think she could have been there officially.’

‘Anyway, she was giving it large,’ Ricky went on, ‘screaming abuse at this Alastair Dunston chap, and then she threw her glass of Buck’s Fizz in his face.’

‘But you don’t know what it was about?’

He shrugged. ‘She called him a lying bastard.’

‘No.’ Morris corrected, holding up a finger. ‘She called him a conniving bastard. She called him a lying pig. I got the impression,’ he added with a coy smile, ‘that she and Dunston had been involved.’

‘His missus didn’t look very happy about it,’ Ricky grinned, obviously enjoying the memory, ‘neither did he, standing there, face all dripping with orange.’

‘What happened to Sandy?’ I asked

‘She was escorted from the premises by hotel staff.’

‘But the police weren’t called?’

‘No, although technically,’ Morris added, thoughtfully polishing his gold-rimmed specs, ‘I suppose it was an assault.’

‘Fascinating. Do we know anything about this Councillor Dunston?’

He frowned. ‘Isn’t he behind that new development they want to build at Woodland? There’s been a lot of fuss about it in the paper. Lots of objections. Perhaps Sandy’s been covering that.’

‘But that wasn’t why she threw a glass of pop in his gob,’ Ricky chuckled. ‘You should’ve seen her face. They’d been shagging, I’d lay good money on it.’ He took another drag on his cigarette, blowing a smoke ring that hovered like a halo above his silver hair. ‘But whatever they’d been up to, I reckon it’s over now.’

I frowned. ‘I don’t think it’s over for Sandy. In the paper she was accused of stalking him, of harassing his family. She’s not allowed within a hundred yards of his house.’

‘Yeh, well, hell hath no fury like a woman scorned. Perhaps he’d tried to give her the elbow and she wasn’t having any. Perhaps she can’t leave it alone.’ He jabbed his cigarette in my direction. ‘Why don’t you turn the tables on her, ring her up and ask her all about it?’

I smiled, but shook my head. I couldn’t do that. A woman scorned, that was what I was. Daniel had accused me of taking stupid risks, recklessly endangering my life. He wasn’t prepared to wait around whilst I got myself killed, he told me, so he put an end to our relationship, almost before it had begun. For the first time since I had known Sandy Thomas, I felt sorry for her.

The following Saturday morning I drew up at No.4, Daison Cottages, the house that Elizabeth shares with fifteen-year-old schoolboy, Oliver Knollys. She poses as his aunt. I know that they’re not really related because, some time ago, I was responsible for putting them together. Elizabeth was homeless, anxious to leave behind a past that had become too interesting, and sleeping in her car. Olly had been secretly living alone since the death of his nan, terrified the social services would find out and take him into care. Sharing the house together seemed to be the perfect solution for them both, and so far, it had worked out well. No one questioned that Elizabeth wasn’t the long-lost relative she claimed to be and she and Olly got on well, drawn together by a love of music and a genial acceptance by them both that they made up the rules as they went along.

Not much had happened in the intervening week. I got back into my working rhythm, soon felt like I hadn’t been away. I managed to catch up with Our Janet before she departed for the wilds of Heck-as-Like, met her over a coffee to discuss her mother’s welfare. Maisie still refused to consider leaving her cottage in Ashburton to live in a care home near her daughter and we both wondered how long she would be able to carry on alone, even with help from me and the care agency Janet employed to look in on her every day. But at ninety-six, Maisie was still going strong. Cussedness can carry you an awfully long way.

For the first few days I couldn’t stop wondering if I’d bump into Daniel in Ashburton. Each time I had to pass the beauty therapist’s, usually on the opposite side of the road, I found I couldn’t drag my eyes from the upper-floor window, where I knew his office was, in case I might catch sight of him. I didn’t, but I did spot Sandy Thomas, hurrying along Sun Street, head down, shoulders hunched, as if she didn’t want anyone to notice her. A couple of people laughed as she went by. Now you know what it feels like,I told her silently, remembering the unwelcome attention her newspaper articles had focused on me. But it was only the thought of a moment. I felt sorry for her really.

I’d been invited up to Daison Cottages that Saturday morning to view Olly’s latest gadget, but when I arrived, Elizabeth was alone in the kitchen. ‘He’s gone up to the woods to retrieve it,’ she explained as she filled the kettle. ‘He’ll be back in a minute.’

Toby, her pale and spindly Siamese cat, was dreaming on top of the stove. I stroked his ears gently then sat down at the kitchen table. ‘What is it this time?’

‘A wildlife camera-trap.’

‘One of those things you see photographers using on the telly?’ I asked. ‘They strap ’em to trees and leave them in the hope that some rare animal might wander by?’

Elizabeth nodded. ‘The camera is set off by movement.’

I grinned. ‘Don’t tell me, Olly wants to be a wildlife photographer.’

‘That is the latest,’ she admitted with a smile.

‘Aren’t those cameras expensive?’

‘Actually no, this one was quite reasonable. He found it on the Internet. When badgers started digging up our potatoes, he decided he’d like to record their night-time activities. He started off filming them in the garden, but their sett is up in the wood there.’

I gazed out of the window. Daison Cottages had originally been built as council houses for agricultural workers, four in a row, with the road in front of them and open country all around. Behind the houses, fields swept up to a wood on top of the hill, which was where the badgers hung out.

‘But I’m restricting filming nights to Fridays and Saturdays,’ Elizabeth went on. ‘Olly hasn’t got time to go up there and retrieve the camera on school mornings, and he spends ages poring over the results.’

‘The badgers don’t mind being film stars then?’

‘Not at all. But Olly needs to buckle down, he’s got GCSEs this year, and these badgers are a great distraction.’

‘Perhaps he’ll get fed up of them.’ In the past he’d been fixated with a drone, but he didn’t seem to fly it much these days. He clattered in through the back door at that moment, looking as if he’d just got up, one half of his shirt hanging down over his trousers and his hair standing up in spikes. Was it my imagination, or was he a little taller than when I’d last seen him? Something was different. Was his fair hair a little darker, greasier? At fifteen, were teenage hormones finally starting to kick in?

‘Hello Juno!’ he grinned. ‘Nice holiday?’ He was clutching the camera, its case patterned in camouflage colours, a green webbing strap attached. He flipped the camera open and used his thumbnail to flip out a memory card. ‘We’ll watch it on the laptop.’ He pulled it across the table towards him, opened the lid and keyed in his password as Elizabeth delivered mugs of coffee and sat down. Olly inserted the memory card into the laptop and an image flashed up on the screen.

‘The camera’s set to night-time,’ he explained, ‘that’s why it’s in black and white.’

We were looking at a picture of the woodland floor and the entrance to the badger’s sett, a black hole in a sloping bank stamped to bare earth by the passage of snouts and paws, fallen leaves in patterns of grey scattered over the ground. Immediately in front of the camera was a pool of white light, the surrounding woodland fading into darkness. Olly had fixed the camera low down on a tree trunk to get the best view of the sett entrance. In the bottom right-hand corner of the screen the time was recorded in glowing numerals, seconds ticking away as a tiny moth danced, ghostly white, in front of the lens. Olly grinned. ‘That’s what started the camera off. It’s triggered by movement, see.’

At 8.47 and 16 seconds the previous evening the first badger’s snout emerged, his eyes shining, two bright reflecting discs. He came out cautiously at first, then sat and scratched his flank, raking at his fur with fearsome hind claws. Another badger emerged from the sett behind him, trundling like a little tank, snuffling at the ground around him. I could hear him grunting. I hadn’t realised the camera recorded sound too. Then the two of them started rolling around, play-fighting. ‘This is great footage, Oll’,’ I told him as a third badger emerged. Then they all vanished like magic, in the blinking of an eye. We were staring once again at the empty forest floor. ‘What happened then?’

‘Timer went. See, movement is what starts the camera filming, but you can set it to film for however long you want. This is set at a minute. Then it stops. That’s why it looks as if they’ve vanished.’

‘Until another movement starts it off again?’

‘Yeh, that’s right. It blinks once a minute. Look at the timer. See, it’s 9.14 now.’

‘But what’s started the camera off this time? I can’t see anything.’

‘Sometimes the wind will start it off, if trees and stuff are moving about in front of the camera.’ He grinned. ‘A spider did it once, dangling down in front of the lens.’

‘Look,’ Elizabeth pointed at a tiny bright spot, travelling from left to right. ‘See that little eye? It’s a mouse or a shrew moving along the ground there.’

The camera blinked again. The mouse had disappeared and another badger stood between the trees, his broad white face stripes glowing in the dark. ‘I didn’t see him come out.’

‘That bank’s full of holes.’ Olly explained, ‘he could have come out anywhere.’ We watched as the badger came right up to the camera, his blunt nose in close-up as he sniffed the lens. Then he turned and disappeared. Badgers kept appearing at intervals, a minute’s footage at a time, snuffling, snorting, scratching, tumbling and playing, until, frankly, I began to find them a bit boring. I cast a glance at Elizabeth, who gave me a wry smile. Olly, meanwhile, was transfixed. ‘More coffee?’ Elizabeth mouthed at me, and I nodded. By now, the timer on the screen was showing two minutes to midnight. Then something scared the badgers, sending them scurrying down into the safety of their sett.

Elizabeth frowned. ‘What was that?’ After a few moments came the shrill yip of a tawny owl, but that was not what had frightened them away. We stared at the screen, patiently waiting for something to appear. Nothing moved. The wind stirred, fluttering leaves. Then came a noise like heavy breathing, almost like sobbing, the crashing and snapping of twigs as something rushed through woodland undergrowth. Deer, perhaps? The noise came again, a tortured drawing in of breath, like a runner who has reached his last gasp and can run no further. No deer made that noise. This was not something, this was someone. The sound was very close to the camera now, but whoever was making it was out of sight. It came again, tortured breath, desperate, heaving. Elizabeth frowned. ‘That sounds like a woman.’

The camera blinked. Something pale, out of focus, stood close up against the lens. The time showed one minute past midnight. Still the noise, that tortured gasping. Whoever it was had stopped in front of the tree, unaware of the camera strapped to it, desperate for breath.

The paleness in front of the lens resolved itself into a shape as it moved away. It was a leg, a woman’s calf and ankle, a foot in a low-heeled sandal. Not a shoe for running in, for running alone in a wood at midnight. As she lurched away from the camera, almost stumbling on the uneven ground, we saw the whole figure: the back of a woman, her dress grey in night-time colour, her hair glowing silvery white. Just for a moment. But as she turned to look behind her, the camera blinked. We didn’t see her face. We were staring at nothing, an empty space between the trees where she’d been standing. It was 12.05. Something else was in front of the camera now: a man’s shoe, a trainer, the gathered cuff of dark jogging trousers. It moved away and we glimpsed a hooded figure following the woman through the trees. The camera blinked again. We waited tensely for whatever was coming next. For a moment, nothing. Then the crashing sound again, the sound of running, closer now, the woman doubling back on herself. Nothing to see except a white moth dancing against the dark. Then a scream quite close, a sickening thwacking noise that came, once, twice, three times. It was 12.09. The camera blinked. Now something was obscuring the lens, a silver cloud of wire-like strands that the bright light shone through.

‘What’s that?’ Olly breathed, his voice barely a whisper.

‘It’s hair,’ I whispered back. ‘I think it’s that woman’s hair.’

‘Then she must be lying …’

She must be lying on the ground, her face turned away from us. We watched in horror as the cloud of hair gradually slid out of sight of the camera, as her body was dragged away. We could hear a man’s heavy breathing as he grunted and muttered, struggled with the effort of dragging her weight. The camera blinked. It was 12.12.

Then it was morning. We were gazing at the woodland floor in daytime colours, in brown and green and gold. We could hear birdsong, see the flickering movements of birds in the undergrowth. Then Olly’s innocent face as he grinned into the camera before he took it down from the tree.

‘Run it back,’ Elizabeth said urgently. ‘Run it back to when we first hear that woman. It’s around midnight.’

We watched again as the scene unfolded. ‘It’s murder, isn’t it?’ Olly’s voice trembled, his pointed little face white with shock. ‘We’re watching a murder.’

Elizabeth reached for her phone. ‘We’ve certainly witnessed an assault.’

‘Olly, when you went to fetch the camera, you didn’t notice anything?’ I asked, ‘Any sign that anyone had been there?’

‘Well, the ground was a bit scuffed up, but I thought that was the badgers.’

Elizabeth was speaking into the phone, asking for police and ambulance.

‘You stay here with Elizabeth, wait for the police,’ I told him. ‘I’m going up there.’

He sprang to his feet. ‘I’m coming with you.’

‘Look, there’s a chance that woman may still be alive. She could be lying there, needing our help. But if … if she’s not … the police won’t want too many people treading about up there.’

‘But you don’t know where the badgers are,’ he protested, ‘the tree where the camera was.’

‘All right, you can show me. Then, you come back here. The police will need you to show them the way.’

As we left, Elizabeth was still patiently explaining what we’d witnessed to the emergency services.

In the bright, golden light of a sunny morning it was difficult to believe what had happened during the night, what had unfolded in shades of grey on the screen like some old horror movie. The daylight world, the world of colour, was warm and kind, alive with birdsong. Olly and I hurried up the hill, reached the edge of the wood and halted, hungry for breath. Beneath the canopy of birch and oak, hazel and holly grew, and a tangle of bramble and blackthorn. The badgers’ sett was not far in, set in a steep bank, the earth around the dark entrance mounded with bare soil where the badgers had dug.

‘I strapped the camera to that one.’ Olly pointed to a birch a few yards away. ‘You can see, low down on the trunk, where I cleared the ivy away.’

He made a step towards it but I grabbed his arm. ‘Don’t go any closer. That’s where she was lying, there might be evidence.’

We looked around. There was no sign of the woman. ‘Where d’you think she … I mean where did he …?’ Olly’s voice tailed off.

‘I don’t know.’ The only thing we did know was that she had been dragged away from the camera, out of sight of the lens. I yelled a hello, my eyes scanning the leafy jigsaw of the woodland floor for any movement. We listened, ears straining for a response. A jay, hunting among the oaks for acorns, shrieked in alarm, and we saw the flash of its white rump, the shimmer of its blue wings as it flew off. Otherwise, silence. But if the woman had been lying in the wood all night, hurt and unable to move, she might not have the strength to call out. She might be dying somewhere close by, hidden, whilst we searched for her and couldn’t find her. A few yards off I made out a clump of crushed and broken ferns. They might have been flattened by something heavy being dragged over them, something like a body. I looked at Olly. ‘I want you to go back now.’

‘I should stay here with you,’ he protested, ‘in case that bloke is still about.’

‘I think he’s long gone.’ A siren sounded in the distance. ‘That’ll be the police or the ambulance. Go on, Oll.’ They’ll need you to show them the way.’

This time he didn’t argue, just nodded and hared off in the direction of home. I followed the trail of broken ferns down a slope into a clearing, stopped and looked around. The wood was obviously being managed, trees pollarded or selectively cut down, sawn logs lying in tidy piles. But there was no sign of the woman. Dark ruffles of fungus had grown like frills around the foot of an oak, one piece broken off, showing the bright yellow flesh within. Had some animal taken a bite from it, or had something broken it off in passing, unnoticed in the night, something dragged along the ground?

I might not have attached any significance to a mound of broken branches heaped nearby, if I hadn’t been searching. I drew close to it and crouched, peering through the network of twigs and concealing foliage. I could see something pale lying in there, something too still. Something dead. Holding my breath, I lifted a branch.

I was staring at a piece of the woman’s dress, pale blue, not grey as it had looked on the night-camera, but, smeared with the green sap of broken plants and scattered with fragments of leaf. I flung the branch aside and tried to drag another out of the way. It was tangled and I was forced to shake it free. I didn’t want to disturb things but I could see the back of the woman’s head, her hair short and wavy, blonde not silver, except where it was clotted dark with blood. I stood up and moved around, trying to see her face. I crouched and stared into dead, doll-like eyes. Her cheek was pressed against the ground, half hidden among the leaf litter. But I could see enough to recognise her. A wave of sadness washed through me. It was Sandy Thomas.

CHAPTER THREE

‘I messed it up, didn’t I, when I went back to get the camera? I trod all over where she’d been lying, where that bloke had stood.’ Olly’s eyes were swimming with unshed tears and his chin trembled.

Detective Inspector Ford smiled. ‘You haven’t messed up anything, Olly,’ he reassured him. ‘If it wasn’t for you and your camera, we’d never have known this dreadful crime had taken place.’ The inspector had viewed the film in grim silence and now the woods were crawling with police.

‘It’s a pity you felt it necessary to disturb the body, though, Miss Browne.’ Detective Sergeant Christine deVille, aka Cruella, was on her usual sparkling form. She doesn’t like me, and if there’s any possibility she can land me in trouble with her boss, she’ll give it her best shot. Today she was looking particularly striking, in a violet blouse that suited her pale skin and dark hair and matched exactly her strange-coloured eyes.

The body,I thought sadly, that’s what Sandy was now. I’ll never forget her eyes looking up at me, dead, robbed of all expression, of life. I stared across the table into Cruella’s icy violets. ‘I thought there was a chance she might still be alive. You can’t tell from the film. It sounds like a vicious attack, but we couldn’t be sure she was dead.’

Her little mouth twisted. ‘It would have been better to wait for the professionals.’

The inspector shot her a look from beneath his heavy eyebrows but made no comment.

‘Did any of you know the victim?’ he asked.

‘I knew her,’ I said. ‘She’d written about me in the newspaper. She was always asking questions about what I was up to.’ I didn’t add that I’d found her a complete pain in the arse. ‘I didn’t know her well, but if I saw her in town, we’d sometimes stop for a chat.’

The inspector sighed. ‘I wonder what she was doing alone in those woods at that time of night.’

‘I saw her up there once,’ Olly said.

We all turned to look at him.

‘When was this?’ Elizabeth asked.

‘One morning, couple of weeks back, must have been a Saturday, when I was getting the camera. It was early and she was out jogging.’

The inspector frowned. ‘Jogging?’

Olly nodded. ‘There’s a track that goes through that bit of wood, goes round in a loop like, meets up with the road. I’ve seen people running on it before.’

‘And you’re sure it was her?’

‘Oh yes. She was going really slowly, puffing and blowing. I remember thinking that she wasn’t very fit.’ He grinned and then looked around at us, stricken with guilt. ‘Sorry.’

‘No, that’s very interesting, Olly. Sergeant,’ he added to Cruella. ‘Get some people up there to search that track. It’s possible our victim went that way last night.’

‘Sir.’ She stood up and went outside, talking into her radio. As she did so, there was a tap on the back door and the burly figure of Detective Constable Dean Collins slipped into the room.

‘Any sign of the murder weapon?’ the inspector asked.

‘No sir, but there’s a lot of sawn logs lying about. The medical examiner thinks it’s likely to have been one of those. And we’ve found a car abandoned about a mile up the back road, on the far side of the woods. It’s unlocked, key still in the ignition. I ran a check and it’s registered to the victim.’

‘Well, at least we know how she got there. Forensics on it?’

‘Yes sir, and her handbag was in the car. No phone, unfortunately. But there’s a bill with her address on. It’s possible she was on her way home. She doesn’t live far from here.’

‘Right. Then that’s our next port of call.’ The inspector rose heavily to his feet and held up the camera’s memory card. ‘I’m going to have to keep this, Olly,’ he told him. ‘And no more night-time filming in the wood for now, all right? It’s a crime scene. The badgers will just have to get along without you.’

Olly nodded solemnly, still pale with shock.

‘And no one is to know of the existence of this film.’ His stern gaze swept us all. ‘Absolutely no one must find out about this for the time being. It’s our secret. D’you understand?’

We all nodded.

‘D’you understand, Olly?’ he repeated.

‘I can keep a secret,’ he responded.

I can vouch for that. Olly can keep a secret. He has a whacking great big one buried in his back garden, as a matter of fact.

‘C’mon, Collins. Take statements, Sergeant,’ he added as Cruella slipped back into the kitchen. Dean gave me a sly wink as he followed him out of the door. Cruella sat down at the table, favoured me with a thin smile and sharpened her pencil.

Dean Collins and I are friends. I’m godmother to his daughter, Alice. She’s just over a year old and is soon to be blessed with a brother or sister. Dean’s wife, Gemma, is a few weeks ahead of Kate in the pregnancy department, and I realised, as I laid eyes on her husband that morning, the birth must be imminent. All these babies. When I was in London, I’d managed to catch up with an old university friend of mine, Jade, who as well as enjoying a successful career as a financial analyst and marrying a property developer, already has two children, boys seven and five. What about me, she’d asked politely, wasn’t it time I got on with it? Didn’t I feel the old biological clock ticking away? Well, no, quite frankly. There’s obviously something the matter with me. It’s not that I don’t like babies. How can you not like babies? I’m as happy to cuddle a baby as the next woman. But whenever I hand it back to its mother, I am not seized with the longing to possess one of my own. As I say, there’s probably something wrong with me. Anyway, I didn’t feel Dean’s wink that morning had been appropriate in the circumstances, and so I told him on the phone, later that evening.

‘You didn’t phone me to tell me off about winking,’ he answered in flat northern vowels. He was still at the police station; I could tell by the buzz going on in the background.

‘No, of course not. I wanted to know how Gemma’s coming along. It’s not long now, is it?’

‘She’s fine thanks, but you didn’t phone me about that, either.’ He dropped his voice. ‘You want to know if I can tell you anything about the murder of Sandy Thomas.’

How well he knows me. ‘And can you?’

‘You saw the film,’ he said bluntly. ‘We haven’t got much more to go on. Forensics are going over the car and her body is with the pathologist. So, it’s a waiting game at the moment, till we get the results.’

‘Suspects?’

‘Well, the bloke in the film seems likely, but we can’t identify him at present.’

I ignored this attempt at sarcasm. I’d realised during the day just how little I knew about Sandy. I’d certainly no idea where she lived. She lived alone, Dean told me, in a rented cottage about a mile up the road from the place where her car was abandoned. ‘Did she have any family?’