9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

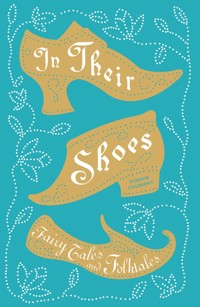

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

These striking short stories from the 1940s and 50s depict women and men caught between the pull of personal desires and profound social change. From a remote peninsula in Cornwall to the ornate drawing rooms of the British Raj, domestic arrangements are rewritten, social customs are revoked and new freedoms are embraced.Expertly chosen and introduced by writer and critic Lucy Scholes, this collection reacquaints readers with mesmerising stories by acclaimed favourites such as Daphne du Maurier and Elizabeth Bowen and introduces lesser-known gems from Frances Bellerby and Inez Holden. Suffused with tension and longing, this collection is a window into a remarkable era of writing.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

A Different Sound

Stories by Mid-Century Women Writers

Selected and Introduced by Lucy Scholes

Pushkin Press

CONTENTS

Introduction Lucy Scholes

8

In Elizabeth Taylor’s ‘The Thames Spread Out’, the story from which this collection takes its title, a middle-aged woman named Rose—who lives alone in a riverside villa paid for by her married lover—is marooned in her bedroom, cut off by the flood waters lapping at the bottom of the stairs. ‘The chimes had a different sound, coming across water instead of grassy meadows,’ Taylor writes, as her protagonist listens to the nearby church clock strike seven in the evening. The flood disrupts Rose’s quiet routine, but it also affords her a vantage point from which to acknowledge that she might be owed more from life than this small, solitary existence, measured out in hair peroxide and peppermint-creams. Like the river that’s breached its banks, Rose too rises up in revolt: in seeing the world around her differently, she’s able to see herself and her life differently too.

I like to think that the eleven stories in the pages that follow offer us a way of seeing women’s writing of the 1940s and 50s differently too, especially when it comes to any preconceptions we might have about gender, genre and era. In an effort to 10 emphasise this, rather than arranging them in the chronological order in which they were first published, I’ve organised the collection alphabetically (by author surname), which I hope gives you a better sense of the impressive scope of these writers’ myriad styles and subjects, while also allowing unexpected parallels and connections to be drawn between pieces that otherwise might never find themselves sat side by side.

Some of the authors included are mainstays of both the period and the medium. I struggled to envisage any collection of mid-twentieth-century short fiction that didn’t include works by those doyennes of the form, the two Elizabeths, Bowen and Taylor; or, for that matter, something by Sylvia Townsend Warner, who was as prolific as she was talented. There are also stories here by writers who are probably better known for their novels: Stella Gibbons of Cold Comfort Farm (1932) fame; and Penelope Mortimer, whose 1962 novel The Pumpkin Eater is now considered a modern classic, a portrait of the entrapment of marriage and motherhood that was revolutionary for the time it was published. Both Daphne du Maurier and Elizabeth Jane Howard wrote novels that won them legions of fans—du Maurier’s Jane Eyre-inspired Gothic romance Rebecca (1938) was a bestseller; while Howard’s late-career, mid-century-set, five-part family saga, The Cazalet Chronicles (1990–2013) is a firm favourite of many readers, myself included—but as you’ll see in the stories here, they each demonstrated very different and distinctive talents in their shorter fiction.

I also wanted to use the assembly of this collection as an opportunity to spotlight some lesser-known and much less widely read writers of the mid-century, of which Frances 11Bellerby is the name least likely to strike a note of familiarity, since the entirety of her work—two novels, three short story collections and four collections of poetry—is currently out of print. Hers was a life marked by extraordinary pain and suffering, much of which she channelled into her writing. Crippled in an accident aged twenty-seven, later, in her fifties, Bellerby endured excruciating radiotherapy after being diagnosed with cancer in both her breasts (a late-stage radical double mastectomy saved her life). But it was the emotional blows—initially that of the tragic death of her eighteen-year-old brother Jack in the First World War, and a decade later the suicide of their mother, who’d never recovered from the loss of her son—that took the most gruelling toll. Long after the fact, Bellerby described Jack death’s as having cracked her and her parents’ lives apart, as evidenced by the fact that she then spent the rest of her life replaying this grief in her fiction, ‘The Cut Finger’ being a case in point. In this story, five-year-old Judith’s world is ‘blown sky-high’ and comes ‘hurtling down in fragments’ all around her after she catches an illicit glimpse of her mother broken down in tears. It’s a Damascene moment of pure emotional devastation, rivalled only by the not dissimilar earth-shattering experience described in Attia Hosain’s ‘The First Party’, the portrait of a young Indian bride’s traumatic encounter with her husband’s supposedly emancipated, Westernised friends.

Born in 1913, the British Indian writer was the first woman to graduate from among the feudal ‘Taluqdari’ families in Lucknow in northern India. Influenced by the nationalist movement of the 1930s, Hosain became a journalist, writer and broadcaster. ‘The First Party’ is taken from her only 12 published short story collection, Phoenix Fled. When, in 1953, this volume first appeared, Hosain had been living in England for six years—she even presented her own women’s programme on the BBC Eastern Service—nevertheless, her stories take us back to India in the early 1940s, in the run-up to partition. It’s one of only three stories in this collection not set in England—along with Bowen’s ‘Summer Night’ and Mortimer’s ‘The Skylight’—but it is the only one written by a woman of colour: a clear indication of the lack of diversity in publishing in the UK during the 1940s and 50s.

For white writers of both sexes, though, the mid-century might actually be described as something of a golden age for short stories, in spite of wartime disruptions and privations, the paper shortage included. Horizon, Penguin New Writing, Lilliput, The Listener, World Review, The Strand Magazine, Modern Reading, John O’London’s Weekly, Time and Tide—these are just a few of the UK-based magazines and periodicals that regularly published short fiction during the war and in the decade after. The only publication in which any of the stories collected here first appeared that’s still around today is The New Yorker—Taylor, Townsend Warner and Mortimer all published regularly in the much-esteemed American magazine—indicating how very different the literary landscape was seventy years ago.

This is not to say it wasn’t a discerning one. The January 1944 edition of Horizon, arguably the most influential English literary publication of the 1940s, famously edited by Cyril Connolly, ran the following editorial note: ‘Horizon will always publish stories of pure realism, but we take the line that experiences connected with the Blitz, the shopping queues, the home 13front, deserted wives, deceived husbands, broken homes, dull jobs, bad schools, group squabbles, are so much a picture of our ordinary life that unless the workmanship is outstanding we are prejudiced against them.’ This tells you something of the rare quality of ‘The Land Girl’, Diana Gardner’s spikey debut, which was published in the December 1940 issue of the magazine. Gardner’s titular narrator’s unapologetic selfishness and cruelty, which culminates in a cleverly calculated act of wanton destruction, isn’t just at odds with our common perception of rosy-cheeked, affable land girls digging for victory; it makes the story feel decidedly modern.

Another regular contributor to Horizon during the war years was Inez Holden, a Bright Young Thing-turned-keenly observant writer of documentary realism. She had a serious socialist agenda, and her fiction empathetically depicted the lives of the working classes. Her father’s family were landed gentry in Warwickshire, and her mother was an Edwardian beauty and famed horsewoman: a background that accounts for their daughter’s acceptance into the inter-war’s raciest set (a milieu that’s reflected in her first three novels, Sweet Charlatan (1929), Born Old, Died Young (1932) and Friend of the Family (1933), all of which are satiric depictions of the giddy antics of the Roaring Twenties). Yet despite these grand beginnings, Holden severed ties with her neglectful family when she was only fifteen years old, and was working poor for most of her life thereafter. Caught between worlds and classes, she was equally as comfortable with privilege and plenty as she was with hardship and hardscrabble. ‘Shocking Weather, Isn’t It?’ is one of her more structurally intricate works. It juxtaposes a young woman’s memories of a pre-war 14 visit she paid to her ne’er-do-well cousin Swithin in prison (where he’s serving time for stealing a car) with her experience in the present moment—that is, in the middle of the war—of visiting the same cousin, now a wing commander sporting medals for his bravery, at a convalescent home. Although the style and tone of the two stories are strikingly different, in the same way that Gardner’s portrait of her land girl challenges stereotype, Holden’s sketch of a once frowned-upon petty criminal-turned fêted patriot is a more complex figure than a cardboard cut-out war hero.

So too, Sylvia Townsend Warner’s ‘Scorched Earth Policy’ offers us a glimpse of the home front that doesn’t quite conform to cosy flag-waving. In it, Townsend Warner introduces us to two septuagenarians who’ve gone above and beyond when it comes to the jingoistic wartime decree to ‘make do and mend’, but who are now gleefully making plans for the desecration of their house, property and provisions should the Germans invade. It crackles with a manic energy: what’s described therein as ‘the positiveness of destruction’.

In contrast with these stories that deal with the war head-on, the conflict is a more shadowy presence in both Bowen’s ‘Summer Night’ and du Maurier’s ‘The Birds’. In the former, we view the happenings in England and Europe from the remove of neutral Ireland. The newspaper reports that an ‘awful air battle’ is raging on the other side of the Irish Sea, but Bowen’s focus is on personal manoeuvres closer to home. A woman named Emma leaves her husband and children alone for the night while she meets her lover for a secret rendezvous. Her absence unwittingly unleashes ‘anarchy […] through the house’, and as the darkness falls, one of Emma’s daughters 15roams naked through the upstairs rooms, anointing herself with snakes and stars drawn in coloured chalks. ‘This is a threatened night,’ thinks Aunt Fran, who eventually discovers and chastises the naughty child, a reference that implicitly connects the devastation that will be wrought by both the aerial battle in the skies above England and that which would ensue should Emma’s adulterous liaison be discovered.

‘The Birds’, meanwhile, draws on the war even more elliptically. Some have read this tale of avian attack as a metaphor for the Blitz, which makes sense since when it was first published in 1952 the nightly bombing raids would still have been a recent memory for many of du Maurier’s readers—as they are for her farm labourer protagonist, Nat. ‘No one down this end of the country knew what the Plymouth folk had seen and suffered,’ he thinks, drawing an almost unconscious correlation in his mind when he’s trying to alert his neighbours to the impending threat of the birds. But at the same time, with the talk of wind ‘from the east’ being behind the otherwise inexplicable behaviour of the local fowl, du Maurier is also tapping into fresh new fears of the menace posed to Britain from behind the Iron Curtain. Reading the story today, though, this hypothesis—that the feathered creatures’ savagery is brought on by a change in weather systems—takes on a grim new relevance as we’re already contending with the horrifying real-life realities of environmental collapse.

Both ‘The Birds’—which, parenthetically, is set in rural Cornwall in the middle of a cruel and cold ‘black winter’, quite a departure from the sunny Northern California landscape that was rendered in lush Technicolor in Hitchcock’s famous film adaptation—and Howard’s creepy canalways-set ghost 16 story ‘Three Miles Up’ sit in contrast to the sharp realism of the other stories here. But I thought it was important they were included, not just because of their virtuosity, but because they point most strongly towards the threat and danger that enveloped this period of history. If, most broadly, the First World War engendered a slew of fiction that engaged with the tragic loss of a generation of young men, the Second World War generated a larger reckoning with the legacies of a conflict that left no corner of the globe untouched, and marked the dawn of a new era of geopolitical wrangling. Between the dropping of the atomic bombs in Japan—which hailed only the beginning of an even more terrifying new potential for mass destruction, one that we’re still very much living in fear of today—and the early years of the Cold War—a different kind of struggle to that previously witnessed, one of subterfuge and silence, of sleeper agents and the fear of the enemy hidden within—it’s no wonder that a sense of peril, however creatively expressed, seeps into much of the fiction writing of the immediate post-war years.

By offering us a portrait in microcosm of the infiltration of Western values and codes of behaviour in Indian society, Hosain’s ‘The First Party’ lets us consider one aspect of mid-century geopolitical flux from a perspective that isn’t white and Western. Despite being one of the briefest stories here, it’s perhaps the most unnervingly and unexpectedly violent. Only ever identified as ‘the wife’, never given a name of her own, at first Hosain’s protagonist feels just timidity and loneliness in the face of the ‘alien sounds’ and ‘strange creatures’ all around her. But as she watches these women, dressed in their flesh-exposing dresses, with their scarlet-painted nails that look like 17‘claws dipped in blood’, drinking cocktails, smoking cigarettes and holding their own with their male counterparts, her ‘discomfort’ changes to ‘uneasy defiance’ and her timorousness turns to red-hot fury as the world as she’s always known it is swiftly and catastrophically reduced to ‘ruins’. Although not as obviously terrifying as ‘The Birds’ and ‘Three Miles Up’, both ‘The First Party’ and Mortimer’s ‘The Skylight’ can, I think, be described as horror stories of a sort.

A masterclass in tension, the latter sees a mother and her five-year-old son arriving at their rented holiday home in the French countryside, only to find the house locked and unassailable by any route other than a tiny open window in the attic. Despite the heat—which ‘sang with the resonant hum of failing consciousness’—the story is suffused with dread. The building is described as ‘grey’ and ‘mean’, its shutters and doors all foreboding ‘heavy black timber’, locked shut with ‘iron bars’, surrounded by ‘dead grass’ through which slinks a rat the size of a cat. Worn out by their journey and unable to think what else to do, the woman climbs up to the roof and lowers her son through the skylight, giving him strict instructions to make his way downstairs and unbolt a window—but the little boy disappears into the gloom and doesn’t return.

That the domestic environment should be a site of horror is apt given the limitations faced by women during the 1950s—and no one writes better about mid-century marital and domestic malaise than Mortimer, both in the short stories that appeared alongside ‘The Skylight’ in her 1960 collection Saturday Lunch with the Brownings and in the novels she penned throughout the 1950s and 1960s. The war released women from their homes, quite literally forcing them into 18 previously male-dominated workplaces, and thus giving them a newfound freedom to take up more space in the city streets than they’d ever been afforded before, something that Elizabeth Bowen explored in her only wartime-set novel, The Heat of the Day (1948). (Incidentally, Bowen wrote and published nothing but short stories during the conflict itself, believing the more fragmented, truncated form was the only medium able to accurately render the almost hallucinatory ‘disjected snapshots’ that comprised wartime urban existence; something she’d experienced first-hand. Rather than fleeing the city for the safety of the house she had in rural Ireland, the Anglo-Irish writer bravely remained in London.) But, as had also happened at the end of the First World War, the soldiers who made it home came looking to pick up where they’d left off, which meant that the women who’d worked these jobs in the men’s absence were shunted back into the domestic sphere, while others who’d been employed as part of the war effort found their roles simply didn’t exist any more.

None of these stories could be called feminist in any real sense of the term—it’s too early for that. And neither, I suspect, would many of their authors have welcomed the description either—at least not at the time these stories were written; though, as I mentioned, today Mortimer is recognised as one of the first writers to use her fiction to pick apart the mid-century myth of domestic bliss, and today her work can be read as companion pieces to Betty Friedan’s era-defining The Feminine Mystique (1963), among other key second-wave feminist texts. It’s important to note, though, that both Townsend Warner and du Maurier pushed against gendered stereotypes, embracing more unconventional ways of living 19and identifying. The former dwelt openly with her partner Valentine Ackland, and together they joined the Communist Party (as a consequence of which they were monitored by MI5 for many years), as well as travelling to Spain in 1936 to fight against fascism. And du Maurier understood herself as being split between two very distinct masculine and feminine identities. Her male alter ego began life as a keen schoolboy cricketer she named Eric Avon, the boy whom she then shut away in a box and only later set free in the guise of the various male narrators found in her fiction, or during the smattering of romantic and sexual relationships she had with women. This doesn’t, however, mean there aren’t moments of emancipation and empowerment to be found in this collection—whether it’s Bowen’s protagonist’s mutiny against her marriage, Rose’s rebellion in ‘The Thames Spread Out’, or Gardner’s land girl’s devious plan, to name just some—even if they’re not immediately recognised as such. The short story, Bowen once declared, is a form that ‘allows for what is crazy about humanity: obstinacies, inordinate heroisms, “immortal longings”’. You’ll meet all of these things—and more—in the eleven stories that follow, and I hope you’ll be as enchanted as I am by the breadth of talent that’s on display.

—London, May 202220

The Cut Finger Frances Bellerby

22

One day not long after Christmas they said to the five-year-old child: ‘Judith, would you like to go and stay at the seaside? Just the three of us, when Nicholas has gone back school.’

‘Well, I think I would,’ she replied, going to the window A stranger would probably have thought her uninterested.

The truth was that the idea astounded and overwhelmed her. It was too new to be accepted with equanimity, too far outside her experience actual or imaginative. It had never been realised by Judith that the seaside continued beyond the golden stretch of summer holidays. Yet now all in a moment she had to grasp that it was possible to go there when tangerines, tinsel and holly were still realities; when the days were grey and cold, the trees without leaves; and when—as they sat at breakfast in the lighted room with the fresh, clear, merry fire in the grate—the trams bumping past outside were gaily illuminated in the prolonged night.

And there was another startling innovation to be considered. Only three would be going to the seaside. Not Nicholas. 24 Presently Judith, heavy with thought, went to find her eight-year-old brother. She guessed where he’d be, and there he was: alone in the scullery, peeling potatoes with the peeler he had given cook for Christmas. Judith watched in silence for a few moments, then said in a stiff way: ‘When you’ve gone back to school we’re going to the seaside.’

Nicholas didn’t look up. Two potatoes had been done without breaking the peel. A third would make the hat-trick. He spoke through clenched teeth. ‘I know. Mother told me. Lucky dogs. Instead of mouldy old Latin grammar and beetles in the tea.’

By this Judith at once knew that he didn’t mind at all; that he was longing for his second term to begin quite as much as he was enjoying every minute of the Christmas holidays. She noticed too the pride and satisfaction with which he peeled the potato.

So out poured her eager questions, for there was nobody like Nicholas for answering any and every question she ever asked.

‘I didn’t know people went to the seaside in winter, did you? Why will we go? Will we have a boat? Will we take sandwiches in the train? Will we bathe if it’s ice?’

Nicholas said loudly: ‘Oh well played, sir! Hat-trick, by Jove!’ And he bowled the potato with an overarm action into a bowl of water. Carefully selecting another, he then replied to his sister.

‘Of course people go to the seaside in winter if they’re ill or something. It’s to make Daddy well, didn’t you even know that? Who’d row you in a boat? You couldn’t take a boatman with you like babies. Anyway, you’re not going to Looe, you’re 25going to Haven, and of course you won’t take sandwiches in the train when it’s only fifteen miles away, as a matter of fact there was a man who lived on nothing but water for sixty-three days, so now do you understand? And there isn’t ice on the sea but of course you won’t bathe in January. Now help me wipe up the floods, as you’re here.’

Judith did his bidding, all her difficulties swept away, her mind happily adapted to the new situation.

Later, she pondered the word ‘Haven’ and what it might contain. The place was unknown to her. Indeed, she had thought ‘the seaside’ to be simply another name for Looe; but the scrap of fresh knowledge could be quickly absorbed now that her mind no longer staggered in bewilderment, quickly, too, she absorbed the idea that they were going to Haven for the purpose of making Daddy well again, and this idea made a splash of bright colour in her mind. The ‘poor Daddy’ attitude had been right, the acceptable, for long enough to dull her first daily expectation that tomorrow would restore the old, happier attitude. But very easily now, having heard the good news from Nicholas, she recalled essential fragments of that permanent ‘Daddy’: tearing out of the house as the tram bumped past, racing after it, leaping on, turning with a sweeping bow to his cheering family at the window whilst the conductor grinned resignedly. Singing Old soldiers never die and The Mountains of Mourne in the bathroom Putting the tea-cosy on his head and prancing into the room to kneel at Mother’s feet and present her with a cauliflower. Sitting on a chair with his legs crossed behind his neck as the vicar’s wife came up the path, and pretending to Mother that he’d got stuck. Telling stories, reading poetry, by firelight to Mother, 26 Nicholas and Judith—beautiful stories and poetry, strangely fascinating, deeply real, holding the three so-different people as if in a magic circle…

For days Judith remained almost completely silent, absorbed in her inner life, luminous with thought.

Haven wasn’t in the least like Looe. The most salient quality about this new seaside was its greyness. A clean, smooth, washed greyness, like beach-stones. Occasionally, it is true, the sea changed itself to a deep pinkish-brown, and the foam of the broken waves became coffee-coloured. And against the grey sky gulls soared, to drift as though in a dream, flashing whiteness as they tilted, leaning on the air. And far out on the lustreless sea white horses tossed their manes in wild glory.

But the roads were grey, the houses were grey, the rocks were grey. The wind was grey; and salty grey—like a licked seashore pebble—tasted the cold air in one’s mouth.

Judith loved everything deeply.

In the mornings she and her mother went shopping whilst her father stayed in bed. They walked along the quiet grey road with a pine-wood on one side and on the other side the low gentle cliff and the sea. They passed a solitary shop, very clean: a dairy. And went on to the shopping street of the small town. Sometimes, when they had finished in the shops, they walked down to the sea-front and along the empty esplanade, and made up stories about the neat little houses in a row facing the sea; every house was so neat and precise, yet no two were exactly alike, which delighted Judith. When the tide was far out there was a wide stretch of mud beyond the flat seaweedy rocks, and sometimes, though the sun never came out properly, this mud 27glinted and glimmered as though lanterns were being shone down on it from behind the clouds. Judith’s mother said that mud was one of the things that made the place so good for people who had been ill; it put the right things into the air for them to breathe. But in any case Judith would have liked the mud.

On the way back the two always paid a visit to the lonely dairy, which sold special cakes and biscuits, and also sugar almonds in four colours: pink, white, blue, amethyst. Smooth and delicate in shape, and with their frail evanescent colours, these sweets seemed of all others the perfect ones to fit the whole situation in which Judith found herself at Haven. Sight, touch, taste, were deeply satisfied.

Back in the landladies’ cosy house—which stood by itself but quite near other small houses—Judith’s mother would go to give the things for lunch to the younger Miss Pearson, whilst Judith kept her father company. He would be downstairs by now, in the big chair by the fire. They talked, or played Snap or Noughts and Crosses, or drew pictures for one another. Then the younger Miss Pearson would come in to lay lunch. Judith thought both sisters remarkably pretty, with their pink faces and blue eyes and silvery hair. She couldn’t see how one could be elder, one younger; to her they looked exactly the same size, but the difference was that one was good at cooking and the other wasn’t, so they did different things. They called one another ‘Sister’.

After lunch Judith rested on her bed upstairs, and her father on the sofa downstairs, and her mother read or mended their clothes by the fire. Then, if it wasn’t too cold, they all went for a short walk. Usually they went as far as the edge of the pine-wood, where there was a seat, and there the grown-ups 28 rested whilst the child played about. When the father had rested long enough they went slowly home again to gas-lit tea in the little, full room with the bright fire made up ready for them. The lacy white cloth would be laid cornerwise on top of the thick red cloth with the bobbled fringe, the heavy red curtains would be drawn across the windows and the door. Judith’s father always lay on the sofa after his walk.

Sometimes, though, the afternoons were different. It would be too cold or too windy for Judith’s father to go out. Then her mother would stay in to read to him, whilst the child played alone in the Pearson sisters’ garden. She always found plenty to do. Her father had often said that was why she was so quiet—because she was so intensely busy, perhaps busiest of all when she stayed perfectly still! People frequently remarked on her quietness.

The garden was interesting to Judith. Very neat and arranged in front, with two tiny lawns and a pebble-path between, and a strip of earth under the privet hedge and railings. But round at the back things could hardly have been more different. Brushes and boxes lay about, and bits of things waiting, perhaps, to be mended. There was a tree, too, which the sisters said was an apple-tree, but the rough grass around it was scattered with nothing but brown stiff leaves. There was also a place which looked like a sentry-box such as Nicholas’s toy soldiers had, but was a kind of lavatory; its roof was orange-coloured with rust. There was also a pump with a small stone trough under it.

One afternoon Judith was surprised to hear that her parents were not going out. The day was as usual grey, but windless, and far warmer than the weather they had been having. ‘Really 29a feeling a Spring in the air!’ the younger Miss Pearson said with gentle triumph as she laid the lunch. And she bestowed on the young people and their little girl the shy blessing of her quick, nervous, compassionate smile. But in spite of all this Judith’s father felt too tired that day to go for a walk.

So Judith went into the garden. First, she chose six pebbles from the path. It was the striking individuality of everything in the world which most delighted and enthralled Judith. When the pebbles had been chosen she took them with her round the house to the back garden, and made her way to the pump. This was her favourite place. It was private, too, for the house only had windows in front and at one side, and from the walled back garden other houses were not in view.

She began to play with the pebbles on the rim of the stone trough, and presently dropped one in by mistake. Pulling up her sleeve, she groped about in the leaf-mouldy water, and at last grasped her pebble and withdrew her hand. Then, with intense excitement, she perceived watery blood colouring one finger. She had cut herself, evidently, on something sharp among the debris on the bottom of the trough!

You couldn’t tell much from watery blood, of course, but Judith carefully dried her finger on the grass, and then squeezed—and behold! A dark red bead appeared, swelled, trembled, collapsed, and flowed quite thickly, even dripped when she shook her hand. This really was a cut! She experimented, swishing the finger to and fro in the trough water; almost at once, no blood was to be seen. But as soon as she took her finger out of the water, redness appeared, and even the water didn’t spoil it now; and when she raised her hand in the air the redness ran down her wrist under her coatsleeve. 30

Then Judith felt a thrill of fear. Not hurtful fear, though, because of course for as long as she could remember she had known the right thing to do with a cut finger: suck it, and go straight to her mother. Even Nicholas acknowledged this to be the right behaviour where a real cut was concerned.

Judith therefore gathered up her pebbles with her free hand, and made for the house, sucking as she went the smooth, thick, dark-tasting blood.

But when she quietly opened the sitting-room door she saw only her father in the room; lying on the sofa, his face turned away from her towards the grey window. Poor Daddy, he must be tired, for he wasn’t even reading. However, in any case he wasn’t the person for cut fingers, so she closed the door again and slowly climbed the stairs, wondering if she were beginning to feel sick with all this blood-drinking.

In her parents’ bedroom her mother lay across one of the beds, face downwards, crying…