Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

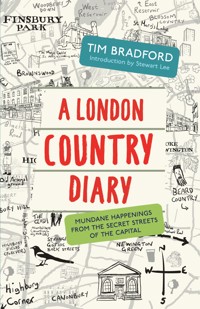

For fifteen years, Tim Bradford has meandered round the quiet streets of his North London home, seeking out the ordinary and the extraordinary, the sublime and the ridiculous. A London Country Diary documents his wanderings – he attempts to rescue a deer in Clissold Park, talks to a magical old man in Holloway, breaks up a fight in Stoke Newington and has issues with foxes in Highbury. And that's just the beginning. All of life is in these pages. Well, some. OK, just a little bit. But with its idiosyncratic wit and charming illustrations, this book is a timely reminder that you can find beauty, humour and life, wherever you call home.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 143

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A LONDON COUNTRYDIARY

Mundane Happenings from the Secret Streets of the Capital

Tim Bradford

Published in the UK in 2014 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.net

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by

Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India,

11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi 110017

Distributed in Canada by

Penguin Books Canada,

90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario M4P 2YE

Published in the USA by Icon Books Ltd,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP, UK

Distributed to the trade in the USA by

Consortium Book Sales and Distribution,

The Keg House, 34 Thirteenth Avenue NE,

Suite 101, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55413-1007

ISBN: 978-184831-705-5

Text and illustrations copyright © 2014 Tim Bradford

Introduction copyright © 2014 Stewart Lee

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any

means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Design by Doug Cheeseman

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Also by Tim Bradford

The Groundwater Diaries

Small Town England

Is Shane MacGowan Still Alive?

To You…

You talked to the magic trees. You helped me fight off the giant pirates. You loved the football tree.

You stood in the leaves with me. You said we should be Vikings. You found a beautiful stone.

You danced on the big tree stump. You persuaded me to buy hot chocolate in the park. You saw how it was all connected.

You lay on the grass and stared at the clouds You walked with me in the wild wind. You showed me new paths.

A SERIES OF NON-ADVENTURES

This rambling and ramshackle diary reflects my need to go wandering, and my attempts to reconcile a need to appreciate and record nature with my love of urban life. As a child in the wilds of rural Lincolnshire I would rarely have to stray more than a mile from the lanes and fields near our house and, thirty years on, I still keep a small orbit – Highbury Corner to the south, Seven Sisters Road/Finsbury Park to the north, Stoke Newington High Street to the east and Holloway Road to the west. Imagine the Hundred Acre Wood populated by drunk football fans, abandoned cars, old pubs, quiet cafes, TVs with kids’ programmes, mums with prams and strange little run-down parks.

The seemingly random entries date from the end of the 90s through to 2014, and in a subtle way chart my steady progress from starry-eyed urban explorer with a desire to articulate the Zen wondrousness of city life to slightly hassled dad trying to catch buses/trying to get the kids to school on time/trying not to burn fish fingers (yet still finding time to walk about/stare out of the window and gawp at stuff).

The common thread is (I hope) my belief in the beauty of the mundane, my love of saluting to magpies, wondering about the trees, drawing plants I don’t know the name of, trying to imagine the past, attempting to befriend mice, watching blossom blowing at the side of the road, trying not to listen to foxes having sex in our back garden, talking to old people, watching buses, breaking up fights, looking at heavy machinery with the kids and my faith in the unifying properties of old urban pubs. All of life is here in these pages.

Actually, it isn’t. It’s just a really tiny slice of life, the non-news that just-about-happens within a square mile of my house.

Tim Bradford, 2014 (on a 19 bus that’s stuck in traffic)

INTRODUCTION

by Stewart Lee

Like some hardy weed clinging to a hostile cliff face, Tim Bradford is himself a survivor. A freelance writer and illustrator, he holds his ground in a North London enclave, until a decade or so ago the natural habitat for him and his kind, but now colonised by hedge-fund managers and business types, cropping the marsh grass upon which he once fed so peacefully, and whereupon he took his ease. Bradford’s ilk are now largely gone from their ancestral homelands, to Brighton, Bristol, Whitstable, and Walthamstow. But Bradford has survived and adapted, like the pubs that spit out their old regulars in search of the gastro dollar, or the unreconstructed working men’s clubs further east, now doubling up as ironic burlesque venues for moustachioed Shoreditch hipsters. And Bradford’s latest work, A London Country Diary, is the literary equivalent of this adaptation.

A London Country Diary quietly appropriates the style and presentation of its rural country diary forebears, among them Edith Blackwell Holden’s posthumously published 1906 opus, The Country Diary of An EdwardianLady, Robert Gibbings’ once best-selling river books of the 40s, and Alison Uttley’s several volumes of recollections of her late 19th century Derbyshire countryside childhood. Like these earlier titles, Bradford’s cornucopia of unrelated observations flits gadfly-like between various subjects and scenes, but all are to be found in the highways and byways of Stoke Newington, Hackney and Highbury, rather than in the fields and waterways of a forgotten and romanticised rural England.

Nonetheless, in the clatter of the Arsenal Cafe, the abandoned bowling green of Clissold Park, the lost New River Milestone, the scavenging foxes of Riversdale Road, and the snails of his own back garden, Bradford begins to apprehend an absurd vision of The Sublime, as surely as his landscape-loving literary forebears Edward Thomas and Ithell Colquhoun saw their own apparitions of The Great God Pan along The Icknield Way, or in the The Living Stones of Ireland and Cornwall, respectively.

Even A London Country Diary’s illustrations seem to echo the presentation of these earlier works. C.F. Tunnicliffe’s vivid etchings illuminate Uttley’s recollections. The polymath Gibbings’ own graceful lines wend through his river diaries. Colquhoun reins in her surrealist tendencies to illustrate her travel books. Bradford describes his own artworks as ‘wang-eyed pop art’, but contextualised within the country diary format, they seem, in their own wang-eyed way, to be firmly in the illustrative tradition of Tunnicliffe or Gibbings or Denys Watkins-Pitchford; flashing in on random details, skewing our perception of the text. And while Bradford’s occasional maps are not strictly geographically accurate, in the way Alfred Wainwright’s pen and ink cartographies of the Lakeland Fells undeniably were, they nonetheless have form and function. I fell into step alongside Bradford early one morning off Blackstock Road to find we were both heading west into town on foot – but his route was that of a rat, steeped in the swiftest routes, not that of some opportunistic sat nav jockey trying his idle hand at minicabbing.

Bradford is not alone in the idea that chance encounters with apparently meaningless phenomena may, if persisted with, provoke some mild form of enlightenment. Arthur Machen (1863-1947) was perhaps the progenitor of Bradford’s breed of mystic-flâneurs. The detailed descriptions of apparently aimless wandering in his 1924 shambles, The London Adventure, quietly approach the profound. In Machen’s wake, also foreshadowing Bradford, we find Frank Baker’s 1948 travelogue, The RoadIs Free, detailing the varied characters and places encountered during a road trip the length of Britain under rationing, that almost seems to be a plea for a new society.

But it is Iain Sinclair who is the post-Velvet Underground Glam Rock Lou Reed to Tim Bradford’s Glam Pop Alvin Stardust. Sinclair’s more obviously experimental poetry and prose of the 70s has latterly been supplanted by more immediately accessible, but no less vital, essays, polemics and playful prose exercises, in the character of an often unreliable narrator, all disguised as apparently unplanned outgrowths from superficially idle urban rambles, many of them through the same postcodes Bradford himself traverses. But where Sinclair sees the city pavements scarred by the claws of global capitalism, corporate greed, and the ongoing annihilation of the individual, Bradford sees simply weeds, slugs, and foxes tugging at an abandoned pizza, and leaves us to make of these symbols whatever we will, their meaning resolutely un-glossed, and only barely implied.

Is Bradford himself in A London Country Diary, or is the Bradford we read about in the book a simplified and satirically useful version of himself, as in the cartoon Bradford that occasionally appears on his website? The Czech surrealist Carel Capek’s 1925 travelogue Letters From England sees the author cast himself as a bewildered innocent abroad, so as best to ridicule our country, slipping into a tradition solidified by the wide-eyed heroes of earlier, albeit fictional, accounts of travellers at odds with unfathomable cultures. Like Raphael as far back as 1516 in Thomas More’s Utopia, Swift’s eponymous Lemuel Gulliver of 1716, or Arthur Dent in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, is Bradford his own self-operated observer-character, a giant beside a Subbuteo figure, a dwarf before the cultural chasm left when Stoke Newington’s Vortex Jazz Club was replaced by a Nando’s?

And is the North London Bradford portrays in A London Country Diary even real? I recognise it, vividly, but various readers of Francis Brett Young’s 1937 description of day-to-day life in Worcestershire village of Monk’s Norton, Portrait of a Village, beautifully illustrated by Joan Hassall’s line drawings, wrote to him to say how accurately it reflected their own memories of the place, despite the fact that Young had completely fabricated the village and all its inhabitants, in part as a parody of this whole strain of country diary literature. Is Bradford assembling a quasi-fictional world on top of a less satisfying real one, by allowing himself to focus in on fascinating details at the expense of the dispiriting reality?

I suspect A London Country Diary may have political and philosophical dimensions, though I am not sure if Bradford is aware of them, and have no intention of asking him. It is not his job to explain. The progress from W.H. Hudson’s 1887 utopian science fiction novel, A Crystal Age, to his romanticised 1910 account of the lives of rural workers on the Wiltshire Downs, A Shepherd’s Life, is all too obvious. Both are politically prescriptive, but the latter used actual observations of the natural world to kick-start a back to the land movement that sucked in a generation of literary types, including Ronald Duncan, whose 1964 memoir of his pre-war bolt for a better life in North Devon, All Men Are Islands, might be another progenitor of A London Country Diary.

None of us can help but look for our own reflection in whatever art we stumble across. I stand at the precipice Bradford has already negotiated, the ‘should I stay or should I go?’ dilemma faced by anyone who came to London as a twenty-something to chase their dreams, and now finds it increasingly unwelcoming, inappropriate to their adult needs. The forests and fields of cultural memory beckon us, whether we actually experienced them in infancy or not, and yet the global population is increasingly urbanised. The lexicon of poetry, of art, of literature, was historically composed of natural images, but who do the woodland flora and fauna of Thomas Hardy, Edward Thomas, and even Ted Hughes speak to now? In supplanting the country diary format of old, however lightheartedly, with his own ramshackle version, Bradford seems to be suggesting that, denied the instant contact high of field and stream, we seek instead our communion with the sublime in the minutiae of city living. His latest book is either the end of an old tradition, or the start of a new one.

I own one of Bradford’s ‘wang-eyed’ paintings. I didn’t know him well when I bought it. His wife had complained that their home was full of his unsold art, so he organised a fire sale at a local library. ‘The Lost Dolmen of Cahermachrusheen’ depicts a stone farm wall, presumably assembled from the wreckage of a missing-presumed-demolished prehistoric burial chamber, once recorded as standing nearby, in the barren Burren of North Clare in the West of Ireland. Bradford depicts the original dolmen, shimmering in the bottom left of the canvas like a Scooby-Doo ghost, a helpful arrow indicating its presumed transformation into the functional containing wall.

My own second-hand copy of W.H. Hudson’s The Book of a Naturalist (a 1919 manifestation of the country diary trope complete with chapter titles like ‘Hints To Adder Seekers’, ‘The Toad As Traveller’, ‘Concerning Lawns and Earthworms’ and ‘A Friendly Rat’) has pressed leaves of trees placed between the pages by the original owner. It is sobering to note that it is statistically likely that at least one of the species preserved is no longer native to the British Isles, or is in imminent danger of disappearance. Bradford accepts that our increased urbanisation, and the demonstrable incremental reduction in the sheer abundance of visible nature around us, renders the country diary literature of old a distant prospect. But he unsentimentally embraces its approach in order to deal with his own urban experience, the ghost of the template he has assimilated still flickering beneath the surface.

Arthur Machen’s 1935 novella, N, imagines then suburban Stoke Newington as a gateway to a hidden world, occasionally glimpsed, that exists in tandem with the streets and parks of N16, overlaid like a tracing paper map. Bradford shows us that the doorway to that alternative world is always open, if we stare long enough at leaves trapped in ice, Victorian gas holders, and faded photos in a chemist’s window.

Stewart Lee, writer/clown

If the definition of a perfect street is somewhere with plentiful dry cleaners, launderettes, old men’s pubs, Chinese takeaways, hardware shops, fruit and veg stalls, cafes and somewhere to buy a hamster, then Blackstock Road is almost perfect (the hamster emporium closed a few years ago).

THE ARSENAL CAFE, BLACKSTOCK ROAD

There are so many with virtually the same name around here. Anyway, they do a great bacon and tomato sandwich on thick crusty white. Free Daily Mirror to read while you’re waiting.

The owner looks like the actor Paul Sorvino.

FOX RODENT HYBRID NUT FIENDS

A mother is walking through the park with a small boy following behind, dribbling a football. A squirrel runs across their path.

‘I used to see red squirrels when I was little,’ says Mum. The boy isn’t listening. He’s doing commentaries to himself as he jogs along.

‘There were lots of them at my Auntie Jo’s house,’ she says. The boy kicks the ball against the fence and makes a crowd noise. His mum sighs.

‘They’re mostly grey squirrels now.’

THE 2008 TWO-PAGES-PER-DAY DESK DIARY

The 2008 two-pages-per-day desk diary is the biggest diary I have ever bought. The bloke at the stationers’ shop asked if I was going to be writing out every single thing that happened during the day in order to fill up the two pages of A4, ‘You know, like “got up in the morning”, that kind of thing.’ It made me think that the 2008 two-pages-per-day desk diary was only on sale in his shop to ensnare passing anal-retentives for the purposes of mockery.

I intend to start doing arm curls of the 2008 two-pages-per-day desk diary. Then when I enter the World Stationery Lifting Championships my local stationer will be laughing on the other side of his face.

HOW TO GET A PLASTIC BOOMERANG BACK FROM YOUR NEXT DOOR NEIGHBOUR

My kids got a yellow plastic boomerang thing a few weeks ago. I attempted to show them how it worked. It sailed over the fence into next door’s garden but didn’t sail back.

An hour or so later I saw our neighbour and said, ‘Our yellow plastic boomerang thing is in your garden. Can you chuck it back for us?’

‘Yeah, sure,’ he said.

‘The yellow plastic boomerang thing will soon be back,’ I said to the kids. But it didn’t come back. For several days it stayed in the same place in their garden. Next time I saw our neighbour I kind of did boomerang actions with my hands. Possibly my attempt at mime looked like I was saying he was a wanker because our neighbour resolutely ignored the boomerang thing for another week. He even walked about in his garden and probably trod on the yellow plastic boomerang thing.

I didn’t see him for ages after that. He was avoiding me. Perhaps he’d tried throwing it back but it kept returning to his garden. Then, just before Christmas, the boomerang thing returned. What a great guy our next door neighbour is.

As soon as it gets a bit warmer I shall be showing my kids how to use it.

FLAME STOOL