1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

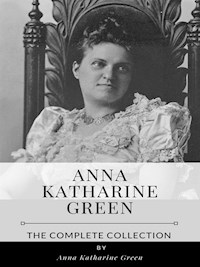

In "A Matter of Millions," Anna Katharine Green weaves a complex tapestry of mystery and intrigue set against the backdrop of late 19th-century America. Known for her pioneering contribution to the detective fiction genre, Green employs meticulous detail and a modern narrative style that combines psychological depth with a keen observation of social mores. The novel explores themes of wealth, trust, and betrayal as the protagonist navigates a labyrinthine plot that questions the true nature of honesty and familial bonds amidst the allure of affluence. Anna Katharine Green, often hailed as the 'mother of American detective fiction,' drew inspiration from her own experiences in a rapidly industrializing society. Her literary career began during a time when women's voices in literature were gaining prominence, and her works often feature strong, intelligent female characters. Green'Äôs extensive knowledge of legal matters, acquired through her father's profession as a lawyer, enhances the authenticity of her plots, making her exploration of moral ambiguities particularly compelling. Readers seeking a richly layered narrative that invites reflection on ethical dilemmas and human behavior will find "A Matter of Millions" to be a captivating addition to their literary collection. Green's masterful storytelling and intricate character development will engage both aficionados of classic detective fiction and newcomers alike.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

A Matter Of Millions

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 The Letter

An old crone stood on the top floor of one of New York’s studio buildings. In her hand was a letter. Looking at it, she studied the superscription carefully, and then, with the same intentness, read the name on one of the doors before her. Hamilton Degraw was on the one, Hamilton Degraw was on the other. Satisfied, she gave a quick glance around her, thrust the letter under the door, and quickly fled.

Within, the young artist answering to this name sat alone, gazing at a nearly completed picture on his easel. He was not painting, only musing, and at the sound of the departing step, which had been too hurried to be noiseless, he looked around and saw the letter. Rising, he picked it up, gave it a quick glance, and opened it. The contents were astonishing.

“Will Mr. Degraw,” so it read, “please accept the inclosed, and in repayment, bring paper and pencil to 391 East street this evening at eight o’clock? A simple sketch is all that is required of him at this time. Afterward, a finished picture may be ordered. When he sees the subject of the sketch, he will realize why so peculiar an hour has been chosen, and why we request promptness and exactitude.

“If Mr. Degraw cannot come, will he send an immediate message to that effect?”

The inclosed was a bank-note of no mean value, and the name signed to the note was, as clearly as he could make out, “Andrea Montelli.”

“Curious!” came from the young man’s lips as he finished the epistle and unfolded the bank-note. “Somewhat peremptory in its demand, but interesting, perhaps, for that very reason. Shall I pursue the adventure? The amount of this money surely makes it worth my while, and then—”

He did not finish the sentence aloud, but his look showed that he was in one of those moods when the prospect of a new or unusual experience possessed a special attraction.

“Eight o’clock!” he repeated after a few minutes, “I wish the note had said six.” And sighing lightly, he went back to the picture on the easel. As he stands surveying it, let us survey him. Though a dissatisfied expression rests upon his countenance (he evidently is not pleased with his day’s work), there is that in his face which irresistibly attracts the eye, and if you look long enough, the heart, so fine are his traits and so full of sympathy his glance and smile. Handsome without doubt, as a man and artist should be, he has that deeper charm which not only awakens the interest but sways the emotions, and which, when added to such perfection of features as distinguishes his face, makes a man a marked figure for good or evil according as the heart behind that charm is actuated by love of self or a generous consideration for others.

By which is the heart of this man moved? We will let his future actions tell, only premising that the bird which sings in one window of his studio and the flower which blows in another, argue that he at least possesses gentle tastes, while the array of swords and guns that gleam on a crimson background above the mantel-piece, betray that the more masculine traits are not absent from his character. Strong, winsome and enthusiastic he appears to us, and such we will take him to be, till events prove us short-sighted, or enlarge mere prepossession in his favor into actual and positive regard. He is tall, and his hair and mustache are black, his eyes gray.

The picture upon which he is gazing is that of a young girl. Though he does not like it, we do, and wonder if his dissatisfaction arises from a failure to express his ideal or from some fault in the subject itself. It cannot be the latter, for never were sweeter features placed upon canvas or a more ideal head presented to the admiration of mankind. Shrined in a golden haze, it smiles upon you with an innocent allurement that ought to repay any artist for no matter how many days of labor or nights of restless dreams. But Hamilton Degraw is not satisfied. Let us see if we can discover the reason for this from the words just hovering on his lips.

“It is beautiful, it is a dream, but where shall I find the face I seek? I would make it a companion piece to this, and I would call the one ‘Dream’ and the other ‘Reality,’ and men would muse upon the ‘Dream,’ but love the ‘Reality.’ But where is there a reality to equal this dream? I shall never find it.”

At half-past seven (all this occurred in the month of May), Mr. Degraw left his studio and proceeded up-town with his paper and pencils.

Chapter 2 A Remarkable Adventure

The number which had been given him was 391 East—street, and, though he had never been in just the locality indicated by this address, he thought he knew the region and what to expect there. Had he not passed through many of these uptown streets, even to the water’s edge, and found them to vary only in the size and pretention of their long and monotonous rows of similarly fashioned brick or stone houses, unless it were by the intrusion of a brewery or a church?

It was, therefore, an agreeable surprise to discover that the especial block in which he was for the moment interested, was not like other blocks, even in this quarter, but was broken up by a stretch of odd-looking houses, which, if somewhat worn and dilapidated, still preserved an air of picturesqueness sadly lacking in most of our third-rate dwellings.

There were four of them, all of a size, all of a grayish-brown color, all with carved strips overhanging the window-tops, and all with square wooden pillars in front. Though their general appearance suggested past wealth, it also as certainly betokened present indigence, notwithstanding the fact that before one of them there stood at this moment a carriage of style and elegance sufficient to prove it the private equipage of a person of means.

Being in an artistic mood, he was greatly attracted by these old-fashioned structures and felt quite an unreasoning desire to enter them.

Long before he came near enough to be sure of the numbers they bore, he had begun to reckon onward from the one he was passing, to see whether 391 would be found on any of them. He soon came to the conclusion that it would, and presently was quite sure of it, and, as he approached nearer, he was pleased to see that it was upon the house before which the carriage was standing. Why he was pleased at this, he would have found it hard to tell. Perhaps, because the house looked a little somber and oppressive as he came within full sight of its closely shuttered windows; and to one of his gay and careless temperament, any hint of companionship was always welcome.

There was a bell at the entrance, but he did not ring it. For just as he stretched out his hand toward it, the door opened, and he saw before him a young servant-girl of a somewhat vacant countenance, who quickly beckoned him in. As his foot crossed the threshold, the clock from a neighboring church pealed out the stroke of eight. “I am prompt,” he inwardly ejaculated.

The hall into which he stepped was dark and seemingly unfurnished. There was no carpet on the floor, and if there were any doors in sight, they were all closed. Feeling it a somewhat chilly welcome, he looked helplessly at the girl, who immediately made another gesture in the direction of a staircase that rose in a spiral a few feet beyond him.

“Does Signor Montelli live up-stairs?” he inquired.

She gave no indication of hearing him, but continued to point to the staircase. “Is she deaf?” was his mental inquiry. It would seem so. Somewhat dashed in his spirits, he went up the first flight and paused again. Darkness and solitude were before him.

“Well, well,” thought he, “this will not do.” And he was about to turn about in retreat, when he remembered the bank-bill in his pocket. “That was not sent to me for nothing,” he concluded; and, taking a closer look into the silent space before him, he perceived four doors.

Making his way to one, he knocked. There was a hurried sound from within, and presently the door was opened and the face of an old crone looked out. Her features lighted up as she saw him, but she did not speak. Pointing as the girl below had done, she indicated the room he should enter, and then withdrew her face and shut the door.

“This is an adventure,” was his mental comment, but he had no further notion of retreat.

Following the guidance of her finger, he crossed the hall and pushed open the door toward which she had pointed. An ordinary room of faded aspect met his eyes.

But barely had he entered it, when he was met by the old crone, and led rather than escorted through another door into an apartment so brilliantly lighted, that for a moment he found himself dazzled and unable to perceive more than the graceful figure of an elegant woman dressed in the richest of carriage attire, bending over what seemed to be a heavily draped couch.

But in another instant, his faculties became clear, and he perceived that what he supposed to be a couch, was in reality a bed of death, and that the woman before him was engaged in strewing blossoms of the richest beauty and most delicate fragrance over the body of a young girl whose face as yet he could not see. Some lillies lay on the floor, half on, half off the edge of a snowy drapery of soft wool, which fell from the couch, taking from it the character of a bed, and lending to the whole scene an aspect of poetic beauty, which was in no wise diminished by the rows of wax candles that burned at the head and the feet of the dead.

It was a picture; and for a moment he looked on it as such; but in another, the lady, whose occupation he had interrupted, turned, and, seeing him, stood upright, meeting his gaze with astonishment and a half-vailed delight in her fine violet eyes; then, as he did not speak and hardly remembered to bow, she colored slightly, and with a strange, swift movement, that took him wholly by surprise, glided from the room.

Then, indeed, he started and tried to follow her. But it was too late. Ere he had reached the threshold, he heard the front door shut, and, in an instant after, the carriage drive away. Strange adventure! For though he did not know her name, he knew her face; had seen it once in a large crowd, and charmed by its perfect lineaments, had brooded upon its memory till he had idealized it into the picture which we have already described as the chief ornament of his studio.

“Am I dreaming?” he asked himself; and he cast a sudden look about him for the old crone who had ushered him into the room, in the hopes of learning from her the name of the lady who had just left them, but by this movement bringing himself nearer to the pulseless figure on the couch, he found himself so enthralled by the exquisite loveliness of the marble-like countenance he now, for the first time, had an opportunity of seeing, that he forgot the impulse that had moved him, and stood petrified in astonishment and delight.

For if what he saw before him formed the picture he was expected to paint, how beautiful it was! Never in his fancy, prolific as it was with lovely forms and faces, had he beheld a countenance like this! It was angelic in its purity and yet human in its quiet look of grief and resignation. It had lines as exquisite as those we see in the ideal heads of the most famous masters, and yet one scarcely saw those lines or the delicate curves of cheek and chin, for the expression which steeped the whole in heavenliest sweetness. If dead, then no living woman was fair; for she seemed to hold all beauty within the scope of her perished personality and to compress into the narrow space shone upon by those two rows of candles all the loveliness and the mystery which had hitherto enshrined the world of womankind in his eyes. Her head reposed upon a white silken pillow, across which streamed a mass of midnight hair in a tangle of great lustrous curls. One lay in motionless beauty on her breast, and so unlike death was the whole vision, that he found himself watching this curl in eager anticipation of seeing it move with the rising and falling of her breath.

But it lay quiescent, as did the waxen lids above the closely shut eyes, and at this discovery, which proved of a surety that she was dead, he felt such a pang of despair, that he knew that whereas he had hitherto looked at a woman with his eyes, he was surveying this one with his heart; that a feeling akin to love had awakened in his breast, and that this feeling was for a dead image—a soulless, pulseless morsel of clay.

The consciousness of his folly made him blush, and drawing back, he again looked about him for the old crone. She was not far away. Seated at one end of the apartment, in a low chair, with her figure bent forward and her head buried in her hands, she was rocking slowly to and fro in what seemed like silent anguish. But when he approached her and she looked up, there were no tears in her eyes nor signs of trouble about her sordid and almost sinister mouth.

“Where is Signor Montelli?” asked the artist. “Is he not present? I allude to the gentleman who wrote me a note this morning requesting me to come here and draw him a picture.”

But she made no reply—that is, no intelligible reply. She murmured some words, but they were in a language he did not recognize, and the mystery seemed to be deepened rather than cleared by her presence.

“Can you not speak English?” he inquired.

She smiled, but evidently did not understand what he said.

“Nor French?”

She smiled again and muttered a few more of her foreign words, this time with a deprecating air and an entreating gesture.

He knew a smattering of Spanish and tried her with that; but with no better result. Discouraged, he repeated the one word they both knew.

“Montelli? Montelli?” he cried, and looked about him with peering eyes.

This time she had the appearance of understanding his meaning. She made a gesture toward the street, then pointed to herself and courtesied. Finally she laid a finger on the portfolio under his arm, smiled, and led him up to the young girl.

There was no misunderstanding this pantomime; he was to draw a picture of the dead. Satisfied and yet vaguely uneasy, he bowed and opened his portfolio. The old crone brought forward a chair, then a small table, and courtesying again, disappeared once more into the background. He took the chair, opened his portfolio, and began to contemplate the picture before him.

It was perfect, even from an artistic standpoint. Had he arranged the couch, the drapery, the flowers and the lights, he could not have made a more harmonious whole. He could not even find an excuse for re-adjusting the locks of the loosely curling hair; all was as it should be, and he had only to put pencil to paper.

But this, which was ordinarily a simple matter for him, had become all at once a most difficult task. He delayed and asked himself questions, feeling the mystery of the situation almost to the point of oppression. Who was this young girl? Who was Andrea Montelli? Who was even this old crone?

What was the disease which had taken the life of this beautiful creature without leaving a trace of its devastating power upon cheek or brow, or even on the dimpled hands that just vaguely showed themselves amid the folds of the drapery that covered her? Had she perished naturally? The thought would come. Was her portrait wished by father and friends? Or was it required only by disinterested officials, and for purposes her beauty made him shrink from contemplating? The presence of this old woman seemed to point to the former supposition as the true one, and yet might it not be the best proof in the world that it was simply hard, stern justice which demanded the reproduction of these features, since it was an easy matter to understand how such a person might be in the pay of the police, but not nearly so easy to be comprehended how she could either be in pay or the confidence of any friends of so dainty and beautiful a creature as she who lay before him?

The contrast between the two was vivid, as were all the accessories of the picture he was expected to draw, to the remaining appointments in the room. Near her and surrounding her were fabrics of softest wool and purest silk, edged with the richest embroideries and covered with costliest blossoms. Beyond her, and outside of the charmed circle created by the prodigal wax tapers, were worn and dingy stuffs and dilapidated furniture.

Not an article from window to door, saving those which were associated with the dead girl, expressed aught but discomfort and poverty, while with her and about her were luxury, wealth and beauty.

It was strange; and, as he considered the matter further, he became more and more convinced that the police had had nothing to do with this display of splendor. No; if they had wished her picture, they would have sent for the photographer, and there would have been no draperies nor candles nor flowers. Some relative, some friend, or, stay—could it be some mere art-lover had wished to preserve on imperishable canvas the extraordinary loveliness which he saw about to vanish forever, and so he had been called in with pencil and paper, and paid for his work beforehand, that he might not retreat from the task when he found that it involved mystery?

But why should it involve mystery? Why should there be no one in the house from whom he could obtain intelligible replies to his queries? Was this merely accident or was it design? The one person he had encountered whose face bespoke intelligence and a desire for communication had surprised him so much by the coincidence between her presence and the picture he had painted, that he had been made for the moment powerless, and so lost the one opportunity offered him to make himself acquainted with the true meaning of the adventure which had befallen him. Was this fortunate or was it not? Was this wealthy lady of high position and incomparable taste the friend or art-lover who had drawn him here? What could be more probable? And yet how greatly was the mystery enhanced if this were the case.

He was gazing steadily at the immovable countenance before him when this idea came; and, fascinated as he was by what he saw, there seemed to rise a film between him and it, out of which there slowly grew on his gaze the face of the unknown visitor. Not the face he had put upon canvas and which was at this moment illuminating the dim recesses of his studio, but of herself as she stood there looking at him with a most human expression of pleasure and appeal, startlingly in contrast with the sumptuousness of her apparel and the dignity of her bearing.

A true face, a good face, with features perfect enough for art, and a smile tender enough to satisfy the most exacting nature. Why did he not thrill before it? Why did not the feeling of contentment which swept over him at its remembrance fill up the void in his heart and make this second recognition of her charms one of promise and unalloyed delight? Because he had seen something more winsome; because she was the Dream, while before him lay the Reality; because his taste and judgment alone awarded to her the palm of beauty, while his heart throbbed to what was expressed in this other face, this other form, which, if dead, had touched a chord in his nature never sounded before, and, as he began to think, would never be sounded again.

The Reality—yes, he had found it. As this belief seized him, he grasped his pencil with avidity. He no longer felt himself held back by doubts. He would draw the picture before him, but as he did so, he would draw another in his mind that should be a basis for his long-hoped-for chef d’ceuvre. Not for the unknown Montelli alone should his pencil fly over the paper, crystallizing into perpetual existence this dream of fading loveliness. He would earn for himself more than the paltry dollars he felt burning in his pocket; he would earn a right to the reproduction of this face, which must henceforth be the expression of his loftiest instincts.

His pencil obeyed his enthusiasm; the features of the sweet unknown began to show themselves upon the broad sheet of paper before him.

He was very much absorbed, or he might have taken a look at the old crone seated in her low chair behind him. If he had done so, would he not have lost himself in further questions? Would he not have wondered why she gazed at him so intently, with eyes that were certainly not lacking in earnestness, if they were in candor? And would he not have queried why her glances only left him to travel to the clock, and so, with one quick flash, to the young girl, and back again to him. There was mystery in all this, if he could have seen it, for there was expectation in her look; an expectation that increased as the minute-hand of the clock moved on toward nine; and expectation here meant interruption, and interruption meant—what? The sly face of the crone made no revelations.

But he saw nothing behind him. Life, hope and love were all, for the moment, concentrated in the end of his pencil, and not the sound of opening doors and hurrying feet could have aroused him now from the dream of creation that engaged him. But there was no sound; all was still; even the mysterious watcher behind him seemed to hold her breath; and when the clock struck, which it presently did, the faint noise seemed to be too much for her aged nerves, for she half rose, and pantingly sank back again, clasping her hands with energy, as if to still the beatings of her heart.

But the artist worked on.

Suddenly there was a change in the room. No one had entered it, and yet it seemed no longer like the same spot. Something strange and unaccountable had occurred; something which caused the moisture to start on Hamilton Degraw’s forehead, and the expectancy in the old crone’s look to deepen into strong excitement. What was it? The artist, catching his breath, listened. What silence! What an oppression of silence! And yet there it comes again, that soft sigh, so light as to be almost inaudible, and yet, to his ears, so thrilling with promise that he leaped to his feet like one who breaks some bond asunder.

At the sight of his eagerness, the old crone, who had risen also, smiles hungrily to herself. If she has heard the sigh also, she shows no anxiety to advance, but stops where she is, content that he should take the precedence, and stand first at the young girl’s side. He was there in an instant, and though no signs of life greeted him from the motionless form, he could not tear his gaze away from her face.

“Sweet one,” welled up from his lips, “was that the sigh of your departed spirit grieving it had left a body that could be so loved? Or is life but pausing in these pulses, and will it—”

He does not finish. How can he, when at these muttered and well-nigh incoherent words he perceives the faintest flush of color suffuse the cheeks? Or was it but a fancy? It has fled now, and the breast does not heave. It must have been a hallucination like the sigh. And yet—and yet—those lids seem to lie less closely. There is something in the face he has not seen there before. It is not life, and yet, surely, it is not death. Where are her friends? Where is there a physician? Why is he not one instead of being a useless artist? With a cry, he turns to the old crone.

“Help!” he shrieks. “See! her lips are growing red! And look at her hands; they are becoming warm! Now—now, they flutter! The roses on her breast are disturbed! She is not dead! We shall have her again—”

He paused, struck even in his frenzy by the abandon of his own words. “I am a fool,” he muttered, “but then the old witch does not understand me. Will she understand what she sees?” And bounding to the old woman’s side, he drew her, wondering and chattering, up between the candles, and pointed to the young girl’s face. As he did so, he uttered an irrepressible cry; for in the instant he had been gone, the miracle had happened, and two wide, dark eyes, luminous with wonder, stared back into his from amid the wreaths of those tangled locks of hair.

Chapter 3 The End Of A Great Ambition

There are some moments which to a sensitive mind seem to be of a dream-like or supernatural character. To Hamilton Degraw this was one of them. Never did it, never could it, seem real. Lost in its wonder, he stood motionless, petrified, gazing back into those orbs which in the glare which now fell upon them seemed welling with light. Had it been death to her, he could not have moved. Not till she threw up her arms, scattering widely the flowers that lay on her breast, did he feel the spell sufficiently broken to comprehend what had occurred. Though he had begrudged Death its victim, though he had longed to see this young girl live, and for the last few minutes had only existed in the hope of doing so, he quailed before the realization, and questioned his own sanity in believing in it Even the shrill cry that now left her lips fell on well-nigh deaf ears; and when, next moment, she raised herself and spoke, he roused with a start, flushing from chin to brow with joy, though the words she uttered were full of terror and suggestive of mystery.

“Alive?” This was her cry. “Then have they deceived me.” And she looked wildly around till her eye rested on the old crone. “Annetta!” she exclaimed, with something more he could not understand, for her English had rippled off into the strange and unknown language of the person she addressed.

The old woman, eager and restless now, answered her in a few quick sentences, at which the maiden—for who could doubt her such?—covered her eyes with her hands and sobbed. But instantly recovering herself, she looked up in despair, and encountering the artist’s gaze, seemed charmed by it so that she forgot to speak, though words of grief and shame were evidently trembling on her tongue.

For him the moment was delightful. He returned her look, and his self-possession failed him.

“You are not dead,” left his lips in almost childish simplicity. “Thank God that appearances deceived me. You are too young, too fair to yield thus soon to the Great Destroyer. I am glad to see you living, though I know nothing of you, not even your name.”

She smiled faintly but piteously.

“Nor do I know you,” she cried. “I am a child lost to the world, lost to life, lost to everything. I should not be here, speaking, breathing, living, suffering. I expected to die, I wanted to die, but some one has deceived me, and I am alive. For what? Oh, for what?”

The artist stared amazed.

From a picture of peace she had become an image of despair. He did not love her less thus, but he felt vaguely out of place and knew not whether to speak or fly.

She saw his trouble and waved him back.

“Since I must live,” she murmured, “let me leave this bed of death.” And without waiting for any assistance, she slid to the floor and stood tottering there, clothed in a long, white garment, bordered with gold, as beautiful as it was odd and poetic. “What trappings are these?” she cried, pointing to the bed and glancing down at her own garments. “If I were not to be allowed to die, why this wealth and beauty of adornment? I am still dreaming, or—” Her eyes fell again on Annetta and she asked her some other question.

Meantime young Degraw had stepped back to the table upon which lay the sketch he had been making. Lifting it up, he turned it toward her.

“Let this explain my presence here,” said he. “It may also make clear to you what otherwise must seem wrapped in mystery. Your picture was desired. I was summoned here to draw it. You must know by whom. The name accompanying the request reads like Andrea Montelli.”

She left the old crone and took a step in his direction and that of the picture he held. A flush was on her cheek, a flush that vaguely irritated him and made him, for the first time, question who this Andrea Montelli really was.

“I do not understand,” said she; “but it is of no consequence. Nothing is of any importance to me now. I am living, that is all I can think of; I am living and the struggle with my fate must re-commence.”

This expression of grief at finding herself once more in the world of human beings, both shocked and touched him.

Though he felt she ought to have some one with her of her own kindred, or, at least, of her own station and sex, he did not see how he could leave her with no one to soothe her but this old woman, who was at once so coarse and so repellent.

“Have you no friends in the house?” he asked.

She sadly shook her head.

“Is there no one I can call?” he persisted, turning now toward the door.

She shivered and caught him by the hand,

“Do not leave me,” she entreated. “Do not go till I have told you why I was so wicked; for you must think me very wicked to try to take my own life.”

“And did you—” He got no further, for the tears which now filled her fathomless eyes called up a suspicious moisture to his own. Strange and wrong as it all was, he had never felt himself so affected. “Tell me your trouble,” he pleaded at last. “Why should one so young and, pardon me, so fair, wish to die before the possibilities of life were fully tested?

“Because,” her eyes flashed fire and a color broke out on her cheeks, “because I had failed.”

“Failed!”

“I am Selina Valdi!”

Selina Valdi! He knew the name. It was that of the young musical debutante who, but a month before, had stood up before a great assembly of expectant listeners, beautiful, fascinating, but tongue-tied. A wonder, with every promise of song in her blazing eyes and upon her trembling lips, but with no voice at her command, no answering sound to the orchestra’s inviting tones, nothing save the moan with which she finally gave up the struggle and sank, overcome and annihilated, behind the falling curtain. Selina Valdi! He remembered the name well, and all the talk and criticism which followed her defeat; and, moved by a boundless compassion, he took her by the hand. Immediately she added: “At least that is the name by which I was known to my teachers and expected to be known to the world. My real name is Jenny—”

Why did she not finish? Why did she look at him so strangely and drop her eyes and shake her head? His expression had been one of expectancy, and all his manner was encouraging. But she seemed to tremble before him, and did not speak the name, only murmured:

“But I forget. I have sworn not to tell my name. I am Selina Valdi without the success which was to make that name illustrious.”

“Poor child!” The words left his lips unconsciously, she looked so desolate and forsaken. “Poor child! your heart was set on success, then! You expected to be a singer.”

“Oh!”

The exclamation spoke volumes. She had clasped her hands and was trembling now, not with weakness but eagerness.

“I had a right to expect it,” she declared. “I can sing; I have a voice that has made every master who has taught me patient and gentle and eager. These rooms have rung, just rung with the notes I have raised; but I cannot face a crowd. At the sight of faces surging in a sea before me, such a terror seizes me that I want to shriek instead of sing; something catches me by the throat and I am suffocated, lost, drowned in a flood of horror to which I can give no name and against which it is useless to struggle. Oh, it is a cruel fate. But I can sing; listen!”

And with sudden impetuosity, her voice soared up in an Italian air, so sweet, so weird, so thrilling, that he stood amazed, entranced, subdued, marveling at the freshness, the power, the soul-moving quality of her tones as well as at the perfection of her manner and the correctness of her interpretation. A living, breathing genius, glorying in her own gift, was before him, and he could but acknowledge it with delight.

She saw his pleasure and rose in dignity and flushed with power. Her voice left the intricate ways of Italian song and deepened into the broader, deeper channels of German opera. It swelled, it rose, it triumphed, till the strange and shabby room became an elysium, and the atmosphere seemed laden with the breath of gods. A genius? She was more, or seemed so while her voice thrilled and her beauty flushed; but when all was still again, and she stood panting and deprecatory before him, then she seemed only a tender child again, craving sympathy and expecting confidence.

“Marvelous! Marvelous!” So he spoke, lifted out of himself, first by her power and then by her humility. “And with such a gift as this you could be discouraged by one failure, overcome by one fright!”

“Ah,” she murmured, “that is how I can sing to you; but I can never sing like that to the multitude.”

“Never?”

“Never.”

“But, dear child, you are not sure of this. You are very young, and after some few months of training you will gain courage and reap a full success. You cannot help it, with your genius. God does not give such a voice to be smothered in obscurity.”

“God?”

With what an indescribable intonation she spoke. He looked at her in amaze.

“Do you believe in God?” she asked, and her face took on a strange look, almost like that of fear.

“I do,” he returned; “and so will you, when you have lived long enough to realize His goodness.”

She shuddered; a change came over her; she no longer looked so young.

“I have not been taught,” she murmured. “I have not been trained in church ways and church thinking. Would it have been better if I had? You look so good; would that have made me good, too?”

The old simplicity and childlike manner were coming back, but with something new in it, that, if not comprehended, affected him deeply.

“Are you not good?” he smiled. “You have committed one sin, I know, but that was the result of frenzy, and certainly does not argue a bad heart. But good, as man reckons goodness, you must be, or your eyes would not be so clear, or your smile so inspiring. If you were happy—”

“If I were happy?” A fresh change had come over her; she seemed to hang upon his words.

“Then you would no longer query if there were a God, but rejoice in the fact that there is one.”

Her face was fallen again, and she seemed to struggle with herself. For some minutes she did not answer.

“Go!” she murmured at last. “I have already kept you too long. Go and forget—” she gasped, gave one look at the crone in the corner to which she had withdrawn, and sank sobbing and troubled in a chair.

He turned to obey her. Something within him told him that he ought to seize upon this excuse to tear himself away from a presence so dangerous to his peace. But when he reached the threshold and turned, as almost any man would have done, for a final look, he found her gazing at him with such despair in her large, dark, limpid eyes, that he made one bound to her side, and seizing her by the hand, exclaimed:

“I will not go till I know just what I leave behind me. You have moved me too much. If you are a true woman you will tell me all that a friend should know, or else dismiss me without this look of grief which holds me back in spite of my better judgment.”

“I cannot help my looks,” she said; “but I can restrain my words. But I will not. I long to have an adviser, I long to have a friend,—outside of the profession,” she added; “outside of that selfish world where all is rivalry, jealousy and distrust. Can you spare the time to listen, or will you come again to-morrow?”

“I had rather linger now. It is not late. See, it is barely ten o’clock, and I am impatient to know my new friend better.”

She sighed, and something like a spasm passed over her face; but it was an innocent face; he had no doubt of her, and he listened with irrepressible emotion to the pathetic story which she proceeded to tell him.

Chapter 4 The Story Of A Strange Girlhood

“I shall not say much about my childhood,” the Signorina Valdi began. “It was like that of many other girls left to grow up in a great city, in the shabby gentility necessitated by small means. My father was a doctor and only half successful, and that in a quarter of the town where most of the patients never pay, and the few that do, pay so little that comfort is scarcely known in the house and luxury never. My mother was an invalid, and, there being no other children, I grew up in the comparatively empty house a creature of fancies and dreams. My voice was my great companion. I dared not sing in the parlors or where my mother could hear me too plainly, but would go away into the garret, where in undisturbed possession of so much empty space, I would sing and trill till I was utterly exhausted or my stock of songs gave out. Later, I took to acting, having seen one opera through the kindness of a school-teacher of mine who knew my passion and had accidentally overheard my voice one day. For even then I never sang before any one, and if by chance I caught any one listening, my throat choked up and I broke out into a cold perspiration. But this was inexperience, as I thought, and I went on cherishing my dreams and acting over and over imaginary scenes from operas which I knew only by name, creating songs and manufacturing situations which must have been sufficiently crude and ridiculous, but which gave my voice a chance and allowed enough of my fervor to expend itself to prevent me from falling ill or becoming desperately dissatisfied and unhappy.

“When I was fourteen, my mother died, and two years after this, my father. But I was not discouraged. I had my voice, and, child that I was, I imagined I had only to lift it in public to have fame and fortune lavished upon me. I was soon undeceived in this regard; for, in the first place, I could not raise my voice in public, and, in the second place, the very first musical adept I saw explained to me how much study and practice were necessary to achieve even the smallest success. Study I did not shrink from and practice was simply a delight. But I had no money, and training is expensive, and so is mere living. I found difficulty in existing till one happy day—was it happy?—I let my voice out in what I supposed to be an empty church, but which in reality contained a great teacher, who, hearing me, thereupon took me in charge and started me on a career which he said would end in wealth and adulation.

“Alas, for me, I believed him, and was no longer hungry or cold or meanly clothed. At least, I did not feel my hunger or the chill of the room in which I worked at sewing or copying, or anything which would furnish me with daily bread. And as for my clothes, they were so certainly destined to change into the silver and gold tissues befitting an opera queen, that I have sometimes laughed, in passing through the streets, to think how the men and women who jostled me so rudely would one day feel proud if I cast them a glance or bestowed upon them the haughtiest of smiles.

“My companion and the only confidante of my dreams was this old Portuguese crone whom you see with me now. I had made her acquaintance in the depths of my poverty, and being none too well off, had found no other friend who could supply her place in faithfulness and devotion. She is not prepossessing to look at, but she loves me; too well I fear, for she would not even let me die, though she knew my secret desperation.

“But this is hurrying on too fast. I studied then, long and faithfully, and practiced every hour, when I was not obliged to work for my subsistence. Hope sustained me, and the days flew by on wings. My eighteenth birthday passed, and the day was set for me to try my voice in concert. Had I carried out this intention, I might have been saved two more years of useless labor and vain hope. But unfortunately, at the last minute, a spirit of opposition seized me, and I refused to test my powers till I could do so with all the eclat of scenery and costume. I would appear as Margherita or not at all, and my foolishness was listened to, and my debut postponed.

“A new teacher now took me in charge. I was able to pay him something, but not much. Never mind; there was a future in store for me; I was but running up a debt which I could easily liquidate by one night of triumphant song. If he were willing to wait—and he seemed to be—I certainly could do this, for my voice and manner and style were improving daily, and ere long the doors of the theaters must open before me, and wealth and honor take the place of indigence and obscurity.

“Looking at me now and remembering my failure, can you imagine such folly? You must be young and poor and have a voice to do it. Why, this room has been peopled with visions, I have seen myself in the possession of every power, every happiness. When my fingers ached with writing, I have thought of the day in store for me, when just my signature would be worth gold. Till then I wanted no companionship, and felt myself untempted by pleasure or wealth. Till I could enjoy all, I wanted nothing. I preferred to take my happiness at a bound, and from these rooms of faded grandeur and sordid suggestions, step at once into the palatial apartments suited to the successful prima donna.

“You can imagine, then, the excitement of those days, when I was informed by my enthusiastic teacher, that the time had come for my appearance, and that after two short months of rehearsal, the stage of the ——should be ready for my debut. If time flew before, it halted now. Never, never would those two months pass! And yet they ought not to have gone so slowly, for I was very busy. The rehearsals themselves were enough to absorb me; and they did, but they never left me satisfied, and I longed to end them. Somehow I needed an audience, or so I thought. I could not warm up to empty benches; but my manager seemed satisfied, and fed me with flatteries, and expended great sums of money on my toilets and the stage accessories. He was sure of success, but not so sure as I was. I can say this now, since I have so egregiously failed. I neither doubted my voice nor my training nor my spirit. I left this room on that fatal night, calm. I took what I thought to be my last look of these miserable apartments, with the quiet farewell of one who feels her fortune assured. I left behind in it many memories, but I went forward to great hopes. When I heard the door close, I had the feeling of something shutting upon my past, and went downstairs and out to my carriage with a different step than that which had been accustomed to mark my departure.

“This feeling followed me to the theater, and increased, rather than diminished, with the putting on of the dainty robes which another’s enthusiasm had procured for me. Nor did the sounds of the orchestra make me quail, nor the voice of the call-boy; nothing moved me till, having crossed the stage, I caught a glimpse—or did I feel the presence—of the vast crowd that awaited in eager expectancy for my first notes. Then, indeed, a dagger entered my heart, and terror, such as the victim of the amphitheater alone can know, caught me in its clutches, paralyzing throat and limbs till I could have welcomed any death that would have annihilated my consciousness. I was before the footlights; I was in the spot where I had pictured myself for years, and I could not sing a note; I could not even fly; I must stop and face the wonder, the pity, the disgust, that must be on every countenance, till Fate should come to my aid and break the spell that bound me.

“It came in the shape of a few stray efforts at applause, doubtless meant for my encouragement. The sound—it was the first I had heard—seemed to loosen the icy fetters that held my limbs enchained, and I sank, suffering frightfully, upon the floor of the stage I was never more to mock by my presence. The curtain was rung down and I was carried away, whither, I hardly knew, and to what I could even then dimly guess, for my heart was broken, and my only earthly hope was at an end.”

“But,” eagerly interposed the artist, “you may be mistaken about this. Stage fright is common. Our greatest actors are subject to it. It is rather thought by them the token of genius, and a promise of future success. Surely, your manager—”

“Do not speak of him, or of my masters. I shudder at the thought of their anger and cruel disappointment. I have never been able to face them, nor never can till I become able to reimburse them for all their useless expense. As for making another attempt, that is impossible. I had rather die! At the mere thought of confronting again that cruel sea of faces, the blood stops flowing in my veins and the world turns black before me. I was not made for a prima donna, or rather, something is lacking in me necessary for success upon the stage. Yet that success is all I have lived for, and without it, what am I?”

“What are you?” The voice of the artist trembled, his eyes spoke the admiration he could not suppress. “A young, beautiful and pure girl. Is that not enough? Most persons would think it wealth.”

“It will not get me bread,” she murmured. “It will not pay my debts, those horrible debts, that weigh upon me like lead. It was this thought that made my return to these walls so bitter. It was this thought which, day by day, forced me into a deeper despair, till at last I only longed for death, as a release from my perplexity and pain. It was a wicked longing, but it was the only one I knew, so last night I sent Annetta for a deadly poison (she had often told me she could get me one) and believing that the powder which she brought me was what she said it was, I took it, and lay down on my own little bed to die. The result is what you know. She deceived me, and gave me a preparation which merely simulates death. Was it wise in her? Time alone can tell,”

“Signorina!” It seemed the natural word for him to use, though every feature of her face and every grace of her person proclaimed her to be an American girl, pure and simple. “I cannot doubt but that the Portuguese did well. I cannot doubt but that the future holds for you all that even your ardent spirit can desire. But—” He paused, affected by her look. From a sad and despairing creature, she had flashed, as it were, into one all cheerfulness and hope. The change was marvelous. He hardly knew the beaming face, the glowing eye. Had his heart betrayed itself in his words? Did she see and respond to the passion which every moment of this sweet but dangerous intercourse was deepening within him? He dared not search her eyes to see. He was content to feel her joy and warm himself at the fire of her growing hope.

“You do not go on,” she breathed. “You think we have talked long enough for to-night. Well, you are right. You have heard enough of misery and I have gained enough of strength to make parting between us easy, just now. So, good-bye, sir, till—”

She looked up and smiled. Ah, how sweet that smile was; how innocent and confiding, He drew back from before it slowly, but firmly; he had fears of his own judgment, of his own strength; he would say good-night and come again when reason should be more under his own control and he could weigh the treasure he coveted before he took it for his own.

But two paces from the door, a fresh thought struck him. The mystery of her awakening had been revealed, but not that which surrounded the picture he had been paid to draw. Till he understood the purpose for which a copy of her face and form had been requested from his pencil, he could not go. The story she had told of her lonely struggle and disastrous failure only made his desire greater. Since there was nothing in her history to account for this mysterious circumstance, how could it be accounted for? Were there facts in her life which she had omitted to relate? He must learn or pass a sleepless night. Coming back, he confronted her again.

Chapter 5 An Importunate Suitor

“Pardon me,” he entreated; “but you have not told me what your pleasure is in regard to this sketch I have made. Shall I destroy it or deliver it to the person who ordered it?”

“Person who ordered it? You confound me,” was her hurried response. “I had forgotten the picture and all connected with it. How was it ordered and when?”

He took a crumpled note from his pocket and showed it to her. By the nearly consumed candles, she read it, puzzled and wondering, to the end.

“Andrea Montelli!” she cried. “I know no such name. It is all a mystery to me.”

At once and without his volition and encouragement, Hamilton Degraw felt himself seized by a sudden doubt which darkened everything before him. All a mystery to her! How could that be. He looked at her and hesitated. Never had she seemed so childlike, so innocent or so pure. Her large eyes, turned up to him, were full of question; her very attitude was one of waiting. It seemed as if she expected him to explain what evidently amazed her. He mastered his doubts and ventured upon a new topic.

“When I came into the room,” said he, “I found bending over you, as you lay upon the couch, a beautiful lady with fair hair and aristocratic features. She had come in a carriage which stood before the door, and when I first saw her, was strewing flowers over the bed and you. See! they lie withering now in heaps upon the floor. Her you must surely know, for both her beauty and her wealth make her conspicuous.”

“I am sorry,” began the signorina, “but I cannot tell you who she is. I might guess.”

“That may be sufficient.”

“But I cannot be sure. There is a lady, both beautiful and rich, who once took an interest in me. She was a pupil of one of my masters, and though I was never introduced to her, I was given to understand that she was watching my career and hoping much for its success. It may have been she; but why she should have sought me out in my despair, when she held herself aloof from me in the time of my prosperity, and why she should have brought flowers and strewed them over my poor body, I cannot explain. But perhaps Annetta can. She was here and may have seen something or gathered something from the lady’s manner which will help us to comprehend the meaning of her actions;” and beckoning the Portuguese toward her, the signorina asked one or two questions, which being duly answered, she turned back to Mr. Degraw and exclaimed:

“It must have been the lady I spoke of. She came without flowers at first, and asking for me, seemed to be greatly shocked when I was pointed out to her, lying, as she supposed, dead. She attempted to question Annetta, but of course got no answer from her, as my good friend does not speak a word of English; and when the lady went away she made a gesture which must have meant that she would return, for in half an hour or so she did come back, bringing these beautiful flowers, which she at once began to strew over me. That is all Annetta can tell. Would you like me to question her further?”

“I would like to hear what she has to say about these candles and your dress and the drapery of your couch. It may explain who Montelli is, and this you as well as myself ought to know.”

“True, true,” came in a murmur from the young girl’s lips. “Annetta must be able to tell how I came to be dressed thus, though the robe itself is no mystery, being one of the costumes prepared for my debut. But the lights, the drapery! all that I cannot understand.”

And she drew the old crone nearer, and holding her by the arm, put question after question, while the young man stood still, gazing from one to the other, devoured by a curiosity that the signorina’s rapidly changing appearance certainly tended to aggravate. For at the explanations which the old woman tendered without hesitation, the young girl’s head sank lower and lower in manifest confusion, while on her cheek and brow a flush slowly gathered, which, if it added to her beauty, could not but add also to the watchful artist’s impatience and distrust.

“What is it? Tell me,” burst from his lips as the Portuguese finally drew back, leaving the signorina standing by that forsaken couch.

“Ah, how can I?” was her cry, though her eyes looked up fearlessly, and the smile on her sensitive mouth was simply a deprecatory one. “It is such a story of—of an unreasoning passion—of—of a love of which I was ignorant, and would never have countenanced if I had known of it, that—”

He appreciated her confusion; he loved her for its evident depth; but he would not help her even by a word to speak. This story, whatever it was, he must know. She saw his determination and summoned up her courage.