1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

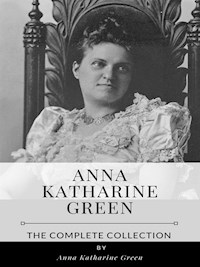

In "The Defence of the Bride," Anna Katharine Green presents a richly woven narrative that intertwines themes of love, betrayal, and the legal implications of marriage. As one of the early pioneers of detective fiction, Green employs intricate plot structures and meticulous character development, painting a vivid portrait of the legal and social dilemmas faced by women in the late 19th century. With her characteristic flair for suspense and keen psychological insight, Green explores the tension between personal desire and societal expectation, an undercurrent that resonates throughout the work. Anna Katharine Green, often referred to as the 'mother of detective fiction,' was deeply influenced by her early exposure to legal matters through her father's work as a lawyer. This background informed her understanding of the complexities surrounding marriage laws and social mores of her time, inspiring her to craft narratives that not only entertain but also challenge prevailing gender norms. Green's writing reflects her advocacy for women's rights during an era of significant change, making her work both relevant and historically significant. Readers seeking an engaging blend of romance and mystery will find "The Defence of the Bride" a compelling read. Green's deft storytelling invites readers to examine the intricacies of human relationships and the stakes involved in societal constructs of duty and honor. This novel stands as a testament to her profound influence on the genre and remains an essential part of feminist literary discourse.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

The Defence Of The Bride

Table of Contents

He was coming from the altar when the tocsin rang alarm, With his fair young wife beside him, lovely in her bridal charm; But he was not one to palter with a duty, or to slight The trumpet-call of honor for his vantage or delight.

Turning from the bride beside him to his stern and martial train, From their midst he summoned to him the brothers of Germain; At the word they stepped before him, nine strong warriors brave and true, From the youngest to the eldest, Enguerrand to mighty Hugh.

“Sons of Germain, to your keeping do I yield my bride to-day. Guard her well as you do love me; guard her well and holily. Dearer than mine own soul to me, you will hold her as your life, ‘Gainst the guile of seeming friendship and the force of open strife.”

“We will guard her,” cried they firmly; and with just another glance On the yearning and despairing in his young wife’s countenance, Gallant Beaufort strode before them down the aisle and through the door, And a shadow came and lingered where the sunlight stood before.

Eight long months the young wife waited, watching from her bridal room For the coming of her husband up the valley forest’s gloom. Eight long months the sons of Germain paced the ramparts and the wall, With their hands upon their halberds ready for the battle-call.

Then there came a sound of trumpets pealing up the vale below, And a dozen floating banners lit the forest with their glow, And the bride arose like morning when it feels the sunlight nigh, And her smile was like a rainbow flashing from a misty sky.

But the eldest son of Germain lifting voice from off the wall, Cried aloud, “It is a stranger’s and not Sir Beaufort’s call; Have you ne’er a slighted lover or a kinsman with a heart Base enough to seek his vengeance at the sharp end of the dart?”

“There is Sassard of the Mountains,” answered she without guile, “While I wedded at the chancel, he stood mocking in the aisle; And my maidens say he swore there that for all my plighted vow, They would see me in his castle yet upon Morency’s brow.”

“It is Sassard and no other then,” her noble guardian cried; “There is craft in yonder summons,” and he rung his sword beside. “To the walls, ye sons of Germain! and as each would hold his life From the bitter shame of falsehood, let us hold our master’s wife.”

“Can you hold her, can you shield her from the breezes that await?” Cried the stinging voice of Sassard from his stand beside the gate. “If you have the power to shield her from the sunlight and the wind, You may shield her from stern Sassard when his falchion is untwined.”

“We can hold her, we can shield her,” leaped like fire from off the wall, And young Enguerrand the valiant, sprang out before them all. “And if breezes bring dishonor, we will guard her from their breath, Though we yield her to the keeping of the sacred arms of Death.”

And with force that never faltered, did they guard her all that day, Though the strength of triple armies seemed to battle in the fray, The old castle’s rugged ramparts holding firm against the foe, As a goodly dyke resisteth the whelming billow’s flow.

But next morning as the sunlight rose in splendor over all, Hugh the mighty, sank heart-wounded in his station on the wall, At the noon the valiant Raoul of the merry eye and heart, Gave his beauty and his jestings to the foeman’s jealous dart.

Gallant Maurice next sank faltering with a death wound ‘neath his hair, But still fighting on till Sassard pressed across him up the stair. Generous Clement followed after, crying as his spirit passed, “Sons of Germain to the rescue, and be loyal to the last!”

Gentle Jaspar, lordly Clarence, Sessamine the doughty brand, Even Henri who had yielded ne’er before to mortal hand; One by one they fall and perish, while the vaunting foemen pour Through the breach and up the courtway to the very turret’s door.

Enguerrand and Stephen only now were left of all that nine, To protect the single stairway from the traitor’s fell design; But with might as ‘twere of thirty, did they wield the axe and brand, Striving in their desperation the fierce onslaught to withstand.

But what man of power so godlike he can stay the billow’s wrack, Or with single-handed weapon hold an hundred foemen back! As the sun turned sadly westward, with a wild despairing cry, Stephen bowed his noble forehead and sank down on earth to die.

“Ah ha!” then cried cruel Sassard with his foot upon the stair, “Have I come to thee, my boaster?” and he whirled his sword in air. “Thou who pratest of thy power to protect her to the death, What think’st thou now of Sassard and the wind’s aspiring breath?”

“What I think let this same show you,” answered fiery Enguerrand, And he poised his lofty battle-ax with sure and steady hand; “Now as Heaven loveth justice, may this deathly weapon fall On the murderer of my brothers and th’ undoer of us all.”

With one mighty whirl he sent it; flashing from his hand it came, Like the lightning from the heavens in a whirl of awful flame, And betwixt the brows of Sassard and his two false eyeballs passed, And the murderer sank before it, like a tree before the blast.

“Now ye minions of a traitor if you look for vengeance, come!” And his voice was like a trumpet when it clangs a victor home. But a cry from far below him rose like thunder upward, “Nay! Let them turn and meet the husband if they hunger for the fray.”

O the yell that sprang to heaven as that voice swept up the stair, And the slaughter dire that followed in another moment there! From the least unto the greatest, from the henchman to the lord, Not a man on all that stairway lived to sheath again his sword.

At the top that flame-bound forehead, at the base that blade of fire— ‘Twas the meeting of two tempests in their potency and ire. Ere the moon could falter inward with its pity and its woe, Beaufort saw the path before him unencumbered of the foe.

Saw his pathway unencumbered and strode up and o’er the floor, Even to the very threshold of his lovely lady’s door, And already in his fancy did he see the golden beam Of her locks upon his shoulder and her sweet eyes’ happy gleam:

When behold a form upstarting from the shadows at his side. That with naked sword uplifted barred the passage to his bride; It was Enguerrand the dauntless, but with staring eyes and hair Blowing wild about a forehead pale as snow in moonlit glare.

“Ah my master, we have held her, we have guarded her,” he said, “Not a shadow of dishonor has so much as touched her head. Twenty wretches lie below there with the brothers of Germain, Twenty foemen of her honor that I, Enguerrand, have slain.

“But one other foe remaineth, one remaineth yet,” he cried, “Which it fits this hand to punish ere you cross unto your bride. It is I, Enguerrand!” shrieked he;”and as I have slain the rest, So I smite this foeman also!”—and his sword plunged through his breast.

O the horror of that moment!”Art thou mad my Enguerrand?” Cried his master, striving wildly to withdraw the fatal brand. But the stern youth smiling sadly, started back from his embrace, While a flash like summer lightning, flickered direful on his face.

“Yes, a traitor worse than Sassard;” and he pointed down the stair, “For my heart has dared to love her whom my hand defended there. While the others fought for honor, I by passion was made strong, Set your heel upon my bosom for my soul has done you wrong.

“But,” and here he swayed and faltered till his knee sank on the floor, Yet in falling turned his forehead ever toward that silent door; “But your warrior hand my master, may take mine without a stain, For my hand has e’er been loyal, and your enemy is slain.”

Through The Trees

If I had known whose face I’d see Above the hedge, beside the rose; If I had known whose voice I’d hear Make music where the wind-flower blow’s,— I had not come; I had not come.

If I had known his deep “I love “ Could make her face so fair to see; If I had known her shy “And I” Could make him stoop so tenderly,— I had not come; I had not come.

But what knew I? The summer breeze Stopped not to cry “Beware! beware!” The vine-wreaths drooping from the trees Caught not my sleeve with soft “Take care!” And so I came, and so I came.

The roses that his hands have plucked, Are sweet to me, are death to me; Between them, as through living flames I pass, I clutch them, crush them, see! The bloom for her, the thorn for me.

The brooks leap up with many a song— I once could sing, like them could sing; They fall; ‘tis like a sigh among A world of joy and blossoming.— Why did I come? Why did I come?

The blue sky burns like altar fires— How sweet her eyes beneath her hair! The green earth lights its fragrant pyres; The wild birds rise and flush the air; God looks and smiles, earth is so fair.

But ah! ‘twixt me and yon bright heaven Two bended heads pass darkling by; And loud above the bird and brook I hear a low “I love,” “And I “— And hide my face. Ah God! Why? Why?

The Nightingale

And now soft night hath ta’en her seat on high, Outbreathing balmy peace o’er all the land; Silent in sleep the dimpled meadows lie Like tired children soothed by mother’s hand. Throughout the valley hums the zephyr bland, Charming the roses from their passionate dreams, To hear the wild and melancholy streams Pulse to the waving of its mystic wand; While large and low eans down the mellow moon, Whose whitely blazing urn doth make a silver noon.

But hark! what heavenly sound is this that now Steals like a dream adown the fragrant vale, Or like a thought across a maiden’s brow, That brings a lambent flush upon the pale? It is the heart-song of the nightingale, Which yearns forever upward in a mist Of subtle sadness, clouding all who list, With softened shadows of her secret ail; And now so purely fills the silence clear, Great Nature seems to hush her beating heart to hear,