1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

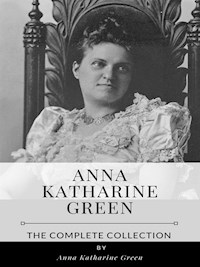

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

In "The Step on the Stair," Anna Katharine Green delivers a masterful blend of mystery and psychological depth, revealing the complexities of human relationships amidst a backdrop of sinister secrets. This novel showcases Green's signature style, characterized by intricate plotting and richly drawn characters, intertwining elements of Gothic fiction with emerging psychological themes. The story unfolds through a carefully constructed narrative that examines the nuances of guilt and the impacts of moral choices, reflecting the Victorian era's growing fascination with the darker aspects of human nature and crime. Anna Katharine Green, often hailed as one of the pioneers of the detective fiction genre, created this novel in an era when women writers were fighting to establish their presence in literature. Her extensive background in law and her acute understanding of social issues deeply informed her writing. Green'Äôs commitment to portraying strong female characters and complex moral dilemmas in her works set her apart as a distinctive voice in her time, influencing future generations of crime writers. For readers seeking an engrossing tale that combines suspense with profound character exploration, "The Step on the Stair" is a compelling choice. This novel not only entertains but also encourages introspection regarding the intricacies of morality, making it an essential read for aficionados of classic mystery literature.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

The Step On The Stair

Table of Contents

Book 1The Three Edgars

Chapter 1Chapter 2Chapter 3Chapter 4Chapter 5Chapter 6Chapter 7Chapter 8Chapter 9Chapter 10Chapter 11Chapter 12Chapter 13Chapter 14Chapter 15

Chapter 1

I had turned the corner at Thirty-fifth Street and was halfway down the block in my search for a number I had just taken from the telephone book when my attention was suddenly diverted by the quick movements and peculiar aspect of a man whom I saw plunging from the doorway of a large office-building some fifty feet or so ahead of me.

Though to all appearance in a desperate hurry to take the taxi-cab waiting for him at the curb, he was so under the influence of some other anxiety almost equally pressing that he stopped before he reached it to give one searching look down the street which, to my amazement, presently centered on myself.

The man was a stranger to me, but evidently I was not so to him, for his expression changed at once as our eyes met and, without waiting for me to advance, he stepped hastily towards me, saying as we came together:

“Mr. Bartholomew, is it not?”

I bowed. He had spoken my name.

“I have been waiting for you many interminable minutes,” he hurriedly continued. “I have had bad news from home—a child hurt—and must go at once. So, if you will pardon the informality, I will hand over to you here and now the letter about which I telephoned you, together with a key which I am assured you will find very useful. I am sorry I cannot stop for further explanations; but you will pardon me, I know. You can have nothing to ask which will not keep till to-morrow?”

“No; but—”

I got no further, something in my tone or something in my look seemed to alarm him for he took an immediate advantage of my hesitation to repeat anxiously:

“You are Mr. Bartholomew, are you not? Edgar Quenton Bartholomew?”

I smiled a polite acquiescence and, taking a card from my pocketbook, handed it to him.

He gave it one glance and passed it back. The name corresponded exactly with the one he had just uttered.

With a muttered apology and a hasty nod, he turned and fairly ran to the waiting taxi-cab. Had he looked back—

But he did not, and I had the doubtful satisfaction of seeing him ride off before I could summon my wits or pocket the articles which had been so unceremoniously thrust upon me.

For what had seemed so right to him seemed anything but right to me. I was Edgar Q. Bartholomew without question, but I was very sure that I was not the Edgar Quenton Bartholomew he thought he was addressing. This I had more than suspected when he first accosted me. But when, after consulting my card, he handed me the letter and its accompanying parcel, all doubt vanished. He had given into my keeping articles meant for another man.

And I knew the man.

Yet I had let this stranger go without an attempt to rid him of his misapprehension. Had seen him hasten away to his injured child without uttering the one word which would have saved him from an error the consequences of which no one, not even myself, could at that moment foresee.

Why did I do this? I call myself a gentleman; moreover I believe myself to be universally considered as such. Why, then—

Let events tell. Follow my next move and look for explanations later.

The man who had accosted me was a lawyer by the name of Miller. Of that I felt assured. Also that he had been coming from his own office when he first rushed into view. Of that office I should be glad to have a momentary glimpse; also I should certainly be much more composed in mind and ready to meet the possible results of my inexcusable action if I knew whether or not the man for whom I had been taken—the other Edgar Q. Bartholomew, would come for that letter and parcel of which I had myself become the guilty possessor.

The first matter could be settled in no time. The directory just inside the building from which I had seen Mr. Miller emerge would give me the number of his office. But to determine just how I might satisfy myself on the other point was not so easy. To take up my stand somewhere in the vicinity—in a doorway, let us say—from which I could watch all who entered the building in which I had located Mr. Miller’s office seemed the natural and moreover the safest way. For the passers-by were many and I could easily slip amongst them and so disappear from view if by chance I perceived the other man of my name approaching. Whereas, if once inside, I should find it difficult to avoid him in case of an encounter.

Policy called for a watch from the street, but who listens to policy at the age of twenty-three; and after a moment of two of indecision, I hurried forward and, entering the building, was soon at a door on the third floor bearing the name of

John E. Miller ATTORNEY AT LAW

Satisfied from the results of my short meeting with Mr. Miller in the street below that he neither knew my person nor that of the other Bartholomew (strange as this latter may seem when one considers the character of the business linking them together), I felt that I had no reason to fear being recognized by any of his clerks; and taking the knob of the door in hand, I boldly sought to enter. But I found the door locked, nor did I receive any response to my knock. Evidently Mr. Miller kept no clerks or they had all left the building when he did.

Annoyed as I was at the mischance, for I had really hoped to come upon some one there of sufficient responsibility to be of assistance to me in my perplexity, I yet derived some gratification from the thought that when the other Bartholomew came, he would meet with the same disappointment.

But would he come? There seemed to be the best of reasons why he should. The appointment made for him by Mr. Miller was one, which, judging from what had just taken place between that gentleman and myself, was of too great importance to be heedlessly ignored. Perhaps in another moment—at the next stop of the elevator—I should behold his gay and careless figure step into sight within twenty feet of me. Did I wish him to find me standing in hesitation before the lawyer’s closed door? No, anything but that, especially as I was by no means sure what I might be led into doing if we thus came eye to eye. The letter in my pocket—the key of whose usefulness I had been assured —was it or was it not in me to hand them over without a fuller knowledge of what I might lose in doing so?

Honestly, I did not know. I should have to see his face—the far from handsome face which nevertheless won all hearts as mine had never done, good-looking though I was said to be even by those who liked me least. If that face wore a smile—I had reason to dread that smile—I might waver and succumb to its peculiar fascination. If on the contrary its expression was dubious or betrayed an undue anxiety, the temptation to leave him in ignorance of what I held would be great and I should probably pass the coming night in secret debate with my own conscience over the untoward situation in which I found myself, himself and one other thus unexpectedly involved.

It would be no more than just, or so I blindly decided as I hastily withdrew into a short hall which providentially opened just opposite the spot where I stood lingering in my indecision.

It was an unnecessary precaution. Strangers and strangers only met my eye as I gazed in anxious scrutiny at the various persons hurrying by in every direction.

Five minutes—ten went by—and still a rush of strangers, none of whom paused even for a moment at Mr. Miller’s door.

Should I waste any more time on such an uncertainty, or should I linger a little while longer in the hope that the other Quenton Bartholomew would yet turn up? I was not surprised at his being late. If ever a man was a slave to his own temperament, that man was he, and what would make most of us hasten, often caused him a needless delay.

I would wait ten, fifteen minutes longer; for petty as the wish may seem to you who as yet have been given no clew to my motives or my reason for them, I felt that it would be a solace for many a bitter hour in the past if I might be the secret witness of this man’s disappointment at having through some freak or a culpable indifference as to time, missed the interview which might mean everything to him.

I should not have to use my eyes to take all this in; hearing would be sufficient. But then if he should chance to turn and glance my way he would not need to see my face in order to recognize me; and the ensuing conversation would not be without its embarrassments for the one hiding the other’s booty in his breast.

No, I would go, notwithstanding the uncertainty it would leave in my mind; and impetuously wheeling about, I was on the point of carrying out this purpose when I noticed for the first time that there was an opening at the extreme end of this short hall, leading to a staircase running down to the one beneath.

This offered me an advantage of which I was not slow to avail myself. Slipping from the open hall on to the platform heading this staircase, I listened without further fear of being seen for any movement which might take place at door 322.

But without results. Though I remained where I was for a full half hour, I heard nothing which betrayed the near-by presence of the man for whom I waited. If a step seemed to halt before the office-door upon which my attention was centered it went speedily on. He whom I half hoped, half dreaded to see failed to appear.

Why should I have expected anything different? Was he not always himself and no other? He keep an appointment?—remember that time is money to most men if not to his own easy self? Hardly, if some present whim, or promising diversion stood in the way. Yet business of this nature, involving—But there! what did it involve? That I did not know—could not know till what lay concealed in my pocket should open up its secrets. My heart jumped at the thought. I was not indifferent if he was. If I left the building now, the letter containing these secrets would have to go with me. The idea of leaving it in the hands of a third party, be he who he may, was an intolerable one. For this night at least, it must remain in my keeping. Perhaps on the morrow I should see my way to some other disposition of the same. At all events, such an opportunity to end a great perplexity seldom comes to any man. I should be a fool to let it slip without a due balancing of the pros and cons incident to all serious dilemmas.

So thinking, I left the building and in twenty minutes was closeted with my problem in a room I had taken that morning at the Marie Antoinette.

For hours I busied myself with it, in an effort to determine whether I should open the letter bearing my name but which I was certain was not intended for me, or to let it lie untampered with till I could communicate with the man who had a legal right to it.

It was not the simple question that it seems. Read on, and I think you will ultimately agree with me that I was right in giving the matter some thought before yielding to the instinctive impulse of an honest man.

Chapter 2

My Uncle, Edgar Quenton Bartholomew, was a man in a thousand. In everything he was remarkable. Physically little short of a giant, but handsome as few are handsome, he had a mind and heart measuring up to his other advantages.

Had fortune placed him differently—had he lived where talent is recognized and a man’s faculties are given full play—he might have been numbered among the country’s greatest instead of being the boast of a small town which only half appreciated the personality it so ignorantly exalted. His early life, even his middle age I leave to your imagination. It is of his latter days I would speak; days full of a quiet tragedy for which the hitherto even tenor of his life had poorly prepared him.

Though I was one of the only two male relatives left to him, I had grown to manhood before Fate brought us face to face and his troubles as well as mine began. I was the son of his next younger brother and had been brought up abroad where my father had married. I was given my uncle’s name but this led to little beyond an acknowledgment of our relationship in the shape of a generous gift each year on my birthday, until by the death of my mother who had outlived my father twenty years, I was left free to follow my natural spirit of adventure and to make the acquaintance of one whom I had been brought up to consider as a man of unbounded wealth and decided consequence.

That in doing this I was to quit a safe and quiet life, and enter upon personal hazard and many a disturbing problem,

I little realized. But had it been given me to foresee this I probably would have taken passage just the same and perhaps with even more youthful gusto. Have I not said that my temperament was naturally adventurous?

I arrived in New York, had my three weeks of pleasure in town, then started north for the small city from which my uncle’s letters had invariably been postmarked. I had not advised him of my coming. With the unconscious egotism of youth I wanted to surprise him and his lovely young daughter about whom I had had many a dream.

Edgar Quenton Bartholomew sending up his card to Edgar Quenton Bartholomew tickled my fancy. I had forgotten or rather ignored the fact that there was still another of our name, the son of a yet younger brother whom I had not seen and of whom I had heard so little that he was really a negligible factor in the plans I had laid out for myself.

This third Edgar was still a negligible factor when on reaching C— I stepped from the train and made my way into the station where I proposed to get some information as to the location of my uncle’s home. It was while thus engaged that I was startled and almost thrown off my balance by seeing in the hand of a liveried chauffeur awaiting his turn at the ticket office, a large gripsack bearing the initials E. Q. B.—which you will remember were not only mine but those of my unknown cousin.

There was but one conclusion to be drawn from this circumstance. My uncle’s second namesake—the nephew who possibly lived with him—was on the point of leaving town; and whether I welcomed the fact or not, must at that very moment be somewhere in the crowd surrounding me or on the platform outside.

More startled than gratified by this discovery, I impulsively reversed the bag I was carrying so as to effectively conceal from view the initials which gave away my own identity.

Why? Most any other man in my position would have rejoiced at such an opportunity to make himself known to one so closely allied to himself before the fast coming train had carried him away. But I had my own conception of how and where my introduction to my American relatives should take place. It had been my dream for weeks, and I was in no mood to see it changed simply because my uncle’s second namesake chose to take a journey just as I was entering the town. He was young and I was young; we could both afford to wait. It was not about his image that my fancies lingered.

Here the crowd of outgoing passengers caught me up and I was soon on the outside platform looking about, though with a feeling of inner revulsion of which I should have been ashamed and was not, for the face and figure of a young man answering to my preconceived idea of what my famous uncle’s nephew should be. But I saw no one near or far with whom I could associate in any way the initials I have mentioned, and relieved in mind that the hurrying minutes left me no time for further effort in this direction. I was searching for some one to whom I might properly address my inquiries, when I heard a deep voice from somewhere over my head remark to the chauffeur whom I now saw standing directly in front of me, “Is everything all right? Train on time?” and turned, realizing in an instant upon whom my gaze would fall. Tones so deliberate and so rich with the mellowness of years never could have come from a young man’s throat. It was my uncle, and not my cousin, who stood at my back awaiting the coming train. One glance at his face and figure made any other conclusion impossible.

Here then, in the hurry of departure from town where I had foolishly looked upon him as a fixture, our meeting was to come off. The surprise I had planned had turned into an embarrassment for myself. Instead of a fit setting such as I had often imagined (how the dream came back to me at that incongruous moment! The grand old parlor, of the elegance of which strange stories had come to my ears—my waiting figure, expectant, with eyes on the door opening to admit uncle and cousin, he stately but kind, she curious but shy)—instead of all this, with its glamour of hope and uncertainty, a station platform, with but three minutes in which to state my claim and receive his welcome.

Could any circumstances have been more prejudicial to my high hopes? Yet must I make my attempt. If I let this opportunity slip, I might never have another. Who knows! He might be going away for weeks, perhaps for months. Danger lurks in long delays. I dared not remain silent.

Meantime, I had been taking in his imposing personality. Though anticipating much, I found myself in no wise disappointed. He was all and more than my fancy had painted. If the grandeur of his proportions aroused a feeling of awe, the geniality of his expression softened that feeling into one of a more pleasing nature. He was gifted with the power to win as well as to command; and as I noted this and yielded to an influence such as never before had entered my life, the hardihood with which I had contemplated this meeting received a shock; and a warmth to which my breast was more or less a stranger took the place of the pretense with which I had expected to carry off a situation I was hardly experienced enough in social amenities to handle with suitable propriety.

While this new and unusual feeling lightened my heart and made it easy for my lips to smile, I touched him lightly on the arm (for he was not noticing me at all), and quietly spoke his name.

Now I am by no means a short man, but at the sound of my voice he looked down and meeting the glance of a stranger, nodded and waited for me to speak, which I did with the least circumlocution possible.

Begging him to pardon me for intruding myself upon him at such a moment, I smilingly remarked:

“From the initials I see on the bag in the hand of your chauffeur, I judge that you will not be devoid of all interest in mine, if only because they are so strangely familiar to you.” And with a repetition of my smile which sprang quite unbidden at his look of quick astonishment, I turned my own bag about and let him see the E. Q. B. hitherto hidden from view.

He gave a start, and laying his hand on my shoulder, gazed at me for a moment with an earnestness I would have found it hard to meet five minutes before, and then drew me slightly aside with the remark:

“You are James’ son?”

I nodded.

“You have crossed the ocean and found your way here to see me?”

I nodded again; words did not come with their usual alacrity.

“I do not see your father in your face.”

“No, I favor my mother.”

“She must have been a handsome woman.”

I flushed, not with displeasure, but because I had hoped that he would find something of himself or at least of his family in my personal traits.

“She was the belle of her village, when my father married her,” I nevertheless answered. “She died six weeks ago. That is why I am here; to make your acquaintance and that of my two cousins who up till now have been little more than names to me.”

“I am glad to see you,”—and though the rumble of the approaching train was every moment becoming more audible, he made no move, unless the gesture with which he summoned his chauffeur could be called one. “I was going to Albany, but that city won’t run away, while I am not so sure that you will not, if I left you thus unceremoniously at the first moment of our acquaintance. Bliss, take us back home and tell Wealthy to order the fatted calf.” Then, with a merry glance my way, “We shall have to do our celebrating in peaceful contemplation of each other’s enjoyment. Both Edgar and Orpha are away. But do not be concerned. A man of my build can do wonders in an emergency; and so, I have no doubt, can you. Together, we should be able to make the occasion a memorable one.”

The laugh with which I replied was gay with hope. No premonition of mischief or of any deeper evil disturbed that first exhilaration. We were like boys. He sixty-seven and I twenty-three.

It is an hour I love to look back upon.

Chapter 3

I had always been told that my uncle’s home was one of unusual magnificence but placed in such an undesirable quarter of the city as to occasion surprise that so much money should have been lavished in embellishing a site which in itself was comparatively worthless. And yet while I was thus in a measure prepared for what I was to see, I found the magnificence of the house as well as the unattractiveness of the surroundings much greater than anything my imagination had presumed to picture.

The fact that this man of many millions lived not only in the business section but in the least prosperous portion of it was what I noted first. I could hardly believe that the street we entered was his street until I saw that its name was the one to which our letters had been uniformly addressed. Old fashioned houses, all decent but of the humbler sort, with here and there a sprinkling of shops, lined the way which led up to the huge area of park and dwelling which owned him for its master. Beyond, more street and rows of even humbler dwellings. Why, the choice of this spot for a palace? I tried to keep this question out of my countenance, as we turned into the driveway, and the beauties of the Bartholomew home burst upon me.

I shall find it a difficult house to describe. It is so absolutely the product of a dominant mind bound by no architectural conventions that a mere observer like myself could only wonder, admire and remain silent.

It is built of stone with a curious admixture of wood at one end for which there seems to be no artistic reason. However, one forgets this when once the picturesque effect of the whole mass has seized upon the imagination. To what this effect is due I have never been able to decide. Perhaps the exact proportion of part to part may explain it, or the peculiar grouping of its many chimneys each of individual design, or more likely still, the way its separate roofs slope into each other, insuring a continuous line of beauty. Whatever the cause, the result is as pleasing as it is startling, and with this expression of delight in its general features, I will proceed to give such details of its scope and arrangement as are necessary to a full understanding of my story.

Approached by a double driveway, its great door of entrance opened into what I afterwards found to be a covered court taking the place of an ordinary hall.

Beyond this court, with its elaborate dome of glass sparkling in the sunlight, rose the main facade with its two projecting wings flanking the court on either side; the one on the right to the height of three stories and the one on the left to two, thus leaving to view in the latter case a row of mullioned windows in line with the facade already mentioned.

It was here that wood became predominate, allowing a display of ornamentation, beautiful in itself, but oddly out of keeping with the adjoining stone-work.

Hemming this all in, but not too closely, was a group of wonderful old trees concealing, as I afterwards learned, stables and a collection of outhouses. The whole worthy of its owner and like him in its generous proportions, its unconventionality and a sense of something elusive and perplexing, suggestive of mystery, which same may or may not have been in the builder’s mind when he fashioned this strange structure in his dreams.

Uncle was watching me. Evidently I was not as successful in hiding my feelings as I had supposed. As we stepped from the auto on to the platform leading to the front door—which I noticed as a minor detail, was being held open to us by a man in waiting quite in baronial style —he remarked:

“You have many fine homes in England, but none I dare say, built on the same model as this. There is a reason for the eccentricities you notice. Not all of this house is new. A certain portion dates back a hundred years. I did not wish to demolish this; so the new part, such as you see it, had to be fashioned around it. But you will find it a home both comfortable and hospitable. Welcome to Quenton Court.”

Here he ushered me inside.

Was I prepared for what I saw?

Hardly. I had looked for splendor but not for such a dream of beauty as recalled the wonders of old Granada.

Moorish pillars! Moorish arches in a continuous colonnade extending around three sides of the large square! Above, a dome of amber-tinted glass through which the sunbeams of a cloudless day poured down upon a central fountain tossing aloft its bejeweled sprays from a miracle of carven stonework. Encircling the last a tesselated pavement covered with rugs such as I had never seen in my limited experience of interior furnishings. No couches, no moveables of any sort here, but color—color everywhere, not glaring, but harmonized to an exquisite degree. Through the arches on either side highly appointed rooms could be seen; but to one entering from the front, all that met the eye was the fountain at play backed by a flight of marble steps curving up to a gallery which, like the steps themselves, supported a screen pierced by arches and cut to the fineness of lace-work.

And it was enough; artistry could go no further.

“You like it?”

The hearty tone called me from my dreams.

“There is but one thing lacking,” I smiled; “the figure of my cousin Orpha descending those wonderful stairs.”

For an instant his eyes narrowed. Then he assumed what was probably his business air and said kindly enough but in a way to stop all questioning:

“Orpha is in the Berkshires.” Then laughingly, as we proceeded to enter one of the rooms, “Orpha does look well coming down those stairs.”

She was not mentioned again between us for many days, and then only casually. Yet his heart was full of her. I knew this from the way he talked about her to others.

Chapter 4

I was given a spacious apartment on the third story. It was here that my uncle had his suite and, as I was afterwards told, my cousin Edgar also whenever he chose to make use of it, which was not very often. Mine overlooked the grounds on the east side of the building, and was approached from the main staircase by a winding passageway, and from a rear one by a dozen narrow steps down which I was lucky never to fall. The second story I soon learned was devoted to Orpha and the many guests she was in the habit of entertaining. In her absence, all the rooms on this floor remained closed. During my whole stay I failed to see a single one of its many doors opened.

I met my uncle at table and in the library opening off the court and for a week we got on beautifully together. He seemed to enjoy my companionship and to welcome every effort on my part towards mutual trust and understanding. But the next week saw us no further advanced either in confidence or warmth of affection, and this notwithstanding an ever increasing regard on my part both for his character and attainments. Was the fault, then, in me that he was not able to give me the full response I so ardently desired? Or was it that the strength of his attachment for the second bearer of his name was such as to preclude too hearty a reception of one who might possibly look upon himself as possessing a corresponding claim upon his consideration?

I tried to flatter myself that this and not any real lack in myself was the cause of the slight but quite perceptible break in our mutual understanding. For whenever my cousin’s name came up, which was oftener than was altogether pleasing to me, the light in my uncle’s eye brightened and the richness in his tone grew more marked. Yet when I once ventured to ask him if my cousin had any special bent or predominate taste, he turned sharply aside, with the carefully modulated remark:

“If he has, neither he nor ourselves have ever been able as yet to discover it.”

But he loved him; of that I grew more and more assured as I noted that there was not a room in the great mansion, no, nor a nook, so far as I could see, without a picture of him somewhere on desk, table or mantel. There was even one in my room. Photographs all, but taken at different times of his life from childhood up, and framed every one with that careful taste and lavishness of expense which we only bestow on what is most precious.

I spent a great deal of time studying these pictures. I may have been seen doing so and I may not, having no premonition as to what was in store for me. My interest in them sprang from a different source than a casual onlooker would be apt to conjecture. I was searching for what gave him such a hold on the affections of every sort of person with whom he came in contact. There was no beauty in his countenance nor in so far as I could judge from the various poses in which these photographs had been taken, any distinction in his build or bearing. His expression even lacked that haunting quality which sometimes makes an otherwise ordinary countenance unforgetable. Yet during the fortnight of my first stay under my uncle’s roof I never heard this cousin of mine mentioned in the house or out of it, that I did not observe that quiet illumination of the features on the part of the one speaking which betrays lively admiration if not love.

Was I generous enough to be glad of the favor so unconsciously shown him by those who knew him best? I fear I must acknowledge to the contrary in spite of the prejudice it may arouse against me. For I mean to be frank in these pages and to present myself as I am, faults and all, that you may rate at their full value the difficulties which afterwards beset me.

I was not pleased to find my cousin, unknown quantity though he was, held so firmly in my uncle’s regard, especially as—but here let me cry a moment’s halt while I speak of one who, if hitherto simply alluded to, was much in my thoughts through these half pleasant, half trying days of my early introduction into this family. Orpha did not return, nor was I so happy as to come across her picture anywhere in the house; which, considering the many that were to be seen of Edgar, struck me as extremely odd till I heard that there was a wonderful full length portrait of her in Uncle’s study, which fact afforded an explanation, perhaps, of why I was never asked to accompany him there.

This reticence of his concerning one who must be exceptionally dear to him, taken with the assurances I received from more than one source of the many delightful qualities distinguishing this heiress to many millions, roused in me a curiosity which I saw no immediate prospect of satisfying.

Her father would not talk of her and as soon as I was really convinced that this was no passing whim but a positive determination on his part, I encouraged no one else to do so, out of a feeling of loyalty upon which I fear I prided myself a little too much. For the better part of my stay, then, she held her place in my imagination as a romantic mystery which some day it would be given me to solve. At present she was away on a visit, but visits are not interminable and when she did come back her father would not be able to keep her shut away from all eyes as he did her picture. But the complacency with which I looked forward to this event received a shock when one morning, while still in my room, I overheard a couple of sentences which passed between two of the maids as they went tripping down the walk under my open window.

One was to the effect that their young mistress was to have been home the previous week but for some reason had changed her plans.

“Or her father changed them for her,” laughed a merry voice. “The handsome cousin might put the other out.”

“Oh, no, don’t you think it,” was the quick retort. “No one could put our Mr. Edgar out.”

That was all. Mere servants’ gossip, but it set me thinking, and the more I brooded over it, the more deeply I flushed in shame and dissatisfaction. What if there were some truth in these idle words! What if I were keeping my young cousin from her home! What if this were the secret of that slight decrease in cordiality which my uncle had shown or I felt that he had shown me these last few days. It might well be so, if he had already planned as these chattering girls had intimated in the few sentences I had overheard, a match between his child and his best known, best loved nephew. The pang of extreme dissatisfaction which this thought brought me roused my good sense and sent me to bed that night in a state of self-derision which should have made a man of me. Certainly it was not without some effect, for early the next morning I sought an interview with my uncle in which I thanked him for his hospitality and announced my intention of speedily bidding him good-by as I had come to this country to stay and must be on the look-out for a suitable situation.

He looked pleased; commended me, and gave me half his morning in a discussion of my capabilities and the best plan for utilizing them. When I left him the next day, it was with a feeling of gratitude strangely mingled with sentiments not quite so worthy. He had made me understand without words or any display of coldness that I had come too late upon the scene to alter in any manner his intentions towards his youngest nephew. I should have his aid and sympathy to a reasonable degree but beyond that I need hope for little more unless I should prove myself a man of exceptional probity and talent which same I perceived very plainly he did not in the least expect.

Nor did I blame him.

And so ends the first act of my little drama. You must acknowledge that it gives small promise of a second one of more or less dramatic intensity.

Chapter 5

Two months from that day I was given a desk of my own in a brokerage office in New York city and as the saying is was soon making good. This favorable start in the world of finance I owed entirely to my uncle, without whose influence, and I dare say, without whose money, I could never have got so far in so short a space of time. Was I pleased with my good fortune? Was I even properly grateful for the prospects it offered? In my heart of hearts I suppose I was. But visions would come of the free and easy life of the man I envied, beloved if not approved and looking forward to a continuance of these joys without the sting of doubt to mar his outlook. I had seen my uncle several times but not my cousins. They had remained in C—, happy, as I could well believe, in each other’s companionship.

With this conviction in mind it was certainly wise to forget them. But I was never wise, and moreover I was a very selfish man in those days, as you have already discovered—selfish and self-centered. Was I to remain so? You will have to read further to find out.

Thus things were, when suddenly and without the least warning, a startling change took place in my life and social condition. It happened in this wise. I was dining at a restaurant which I habitually patronized, and being alone, which was my wont also, I was amusing myself by imagining that the young man seated at a neighboring table and also alone was my cousin. Though only a part of his profile was visible, there was that in his general outline highly suggestive of the man whose photographs I had so carefully studied. What might not happen if it were really he! My imagination was hard at work, when he impetuously rose and faced me, and I saw that I had made no mistake; that the two Bartholomews, Edgar Quentons both, were at last confronting each other; and that he as surely recognized me as I did him.

In another moment we had shaken hands and I was acknowledging to myself that a man does not need to have exceptionally good looks to be absolutely pleasing. Though quite assured that he did not cherish any very amiable feelings towards myself, one would never have known it from his smile or from the seemingly spontaneous warmth with which he introduced himself and laughingly added:

“I was told that I should be sure to find you here. I have been entrusted with a message from those at home.”

I motioned him to sit down beside me, which he did with sufficient grace. Then before I could speak, he burst out in a matter-of-fact tone:

“We are to have a ball. You are to come.” His hand was already fumbling in one of his pockets. “Here is the formal invitation. Uncle thought—in fact we both thought —that you would be more likely to accept it if it were accompanied by some preliminary acquaintance between us two. Say, cousin, I think it is quite fortunate that you are a dark man and I a light one; for people can now say the dark Mr. E. Q. Bartholomew or the light one, which will quite preclude any mistakes being made.”

I laughed, so did he, but there was an easy confidence in his laugh which was not in mine. Somehow his remark did not please me. Nor do I flatter myself that the impression I made upon him was any too favorable.

But we continued outwardly cordial. Likewise, I accepted the invitation he had taken so long a trip to deliver and would have offered him a bed in my bachelor apartment had he not already informed me that it was his intention to return home that night.

“Uncle did not seem quite as well as usual this morning,” he explained, “and Orpha made me promise to come back at once. Just a trifling indisposition,” he continued, a little carelessly. “He has always been so robust that the slightest change in him is a source of worry to his devoted daughter.”

It was the first time he had mentioned her, and I may have betrayed my interest, carefully as I sought to hide it; for his smile took on meaning as he lightly remarked:

“This ball is in celebration of an event you will be the first to congratulate me upon when you see our pretty cousin.”

“I am told that she is more than pretty; that she is very lovely,” I observed somewhat coldly.

His gesture was eloquent; yet to me his manner was not that of a supremely happy man. Nor did I like the way he looked me over when we parted as we did after a half hour of desultory conversation. But then it would have been hard for me to find him wholly agreeable after the announcement he had just made, little reason as I had to concern myself over a marriage between one long ago chosen for that honor and a woman I had not even seen.

Chapter 6

Whether I was not over and above eager to attend this ball or whether I was really the victim of several mischances which delayed me over more than one train, I did not arrive in C— till the entertainment at Quenton Court was in full swing. This I knew from the animation observable in the streets leading to my uncle’s home, and in the music I heard as I entered the gate which, for no reason good enough to mention, I had approached on foot.

But though fond of dancing and quite used to scenes of this nature, I felt little or no chagrin over the hour or two of pleasure thus lost. The night was long and I should probably see all, if not too much, of a celebration in which I seemed likely to play an altogether secondary part. Which shows how little we know of what really confronts us; upon what thresholds we stand,—or to use another simile,—how sudden may be the tide which slips us from our moorings.

I had barely stepped from under the awning into the vestibule guarding the side entrance, when I found myself face to face with my uncle’s butler. He was an undemonstrative man but there was something in his countenance as he drew me aside, which disturbed, if it did not alarm me.

“I have been waiting for you, sir,” he said in a tone of suppressed haste. “Mr. Bartholomew wishes to have a few words with you before you enter the ball-room. Will you go straight up to his room?”

“Most assuredly,” I replied, bounding up the narrow staircase used on such occasions.

He did not follow me. I knew the house and the exact location of my uncle’s room. But imperative as my duty was to hasten there without the least delay, a strong temptation came and I lingered on the way for how many minutes I never knew.

The cause was this. The room in which I had rid myself of my great-coat and hat was on the opposite side of the hall from the stair-case running up to the third story. In crossing over to it the lure of the brilliant scene below drew me to the gallery overlooking the court where most of the dancing was taking place.

Once there, I stopped to look, and looking once, I looked again and yet again, and with this last look, my life with its selfish wishes and sordid plans took a turn from which it has never swerved from that day to this.

There is but one factor in life potent enough to work a miracle of this nature.

Love!

I had seen the woman who was to make or unmake me; the only one who had ever roused in me anything more than a pleasing emotion.

It was no mere fancy. Fancy does not remold a man in a moment. Fancy has its ups and downs, its hot minutes and its cold. This was a steady inspiration; an enlargement of the soul such as I had hitherto been a stranger to, and which I knew then, as plainly as I do now, would serve to make my happiness or my misery as Fortune lent her aid or passed me coldly by.

I have called her a woman, but she was hardly that yet. Just a girl rejoicing in the dance. Had she been older I should not have had the temerity to associate her in this blind fashion with my future. But young and care free—a blossom opening to the sun—what wonder that I put no curb on my imagination, but watched her every step and every smile with a delight in which self if assertive triumphed more in its power to give than in its expectation of reward.

It was a wonderful five minutes to come into any man’s life and the experience must have left its impress upon me even if at this culminating point of high feeling I had gone my way to see her face no more.

But Fate was in an impish mood that night. While I still lingered, watching her swaying figure as it floated in and out of the pillared arcade, the whirl of the dance brought her face to face with me, and whether from the attraction of my fixed gaze or from one of those chances which make or mar life, she raised her eyes to the latticed gallery and our glances met.

Was it possible—could it be—that hers rested for an instant longer on mine than the occasion naturally called for? I blushed as I found myself cherishing the thought, —I who had never blushed in all my memory before—and forced myself to look elsewhere and to listen with attention to the music just then rising in a bewildering crash.

I have taken time to relate this, but the minutes of my lingering could not have been many. However, as I have already acknowledged, I have never known the sum of them, and when, at last, struck by a sudden pang of remembrance, I started back from the gallery-railing and made my way up a second flight of stairs to my uncle’s room, I was still so lost to the realities of life that it was with a distinct sense of shock I heard the sound of my own knock on my uncle’s door.

But that threshold once passed, all thought of self—I will not say of her—vanished in a great confusion. For my uncle, as I saw him now, had little in common with my uncle as I saw him last.

Sitting with face turned my way but with head lowered on his breast and all force gone from his great body, he had the appearance of a very sick man or of one engulfed beyond his own control in human misery. Which of the two was it? Sickness I could understand; even the prostration, under some insidious disease, of so powerful a physical organism as that of the once strong man before me. But misery, no; not while my own heart beat so high and the very walls shook with the thrum, thrum of the violin and cello. It was too incongruous.

But if sickness, why did I find him, the master of so many hearts, alone in his room looking for help from one who was little more than a stranger to him? It must be misery, and Edgar, my cousin, the cause. For who but he could inflict a pang capable of working such havoc as this in our uncle’s inflexible nature. Nor was I wrong; for when at some movement I made he lifted his head and our eyes met, he asked abruptly and without any word of welcome, this question:

“Have you seen Edgar? Does he know that you are here?”

I shook my head, in secret wonder that I had given him a thought since setting foot in the house.

“I have had no opportunity of seeing him,” I hastened In explain. “He is doubtless with the dancers.”

“Is he with the dancers?” It was said somewhat bitterly; but not in a way which called for reply. Then with, feverish abruptness, “Sit down, I want to talk to you.”

I took the first chair which offered and as I did so, became aware of a hitherto unobserved presence at the farther end of the room. He was not alone, then, it seemed. Some one was keeping watch. Who? I was soon to know for he turned almost immediately in the direction I have named and in a tone as far removed as possible from the ringing one to which I was accustomed, he spoke the name of Wealthy, saying, as a middle-aged woman came forward, that he would like to be alone for a little while with this nephew who was such a stranger.

She passed me in going out—a wholesome, kindly looking woman whom I faintly remembered to have seen once or twice during my former visit. As she stopped to lift the portiere guarding the passage-way leading to the door, she cast me a glance over her shoulder. It was full of anxious doubt.

I answered it with a nod of understanding, then turned to my uncle whose countenance was now lit with a purpose which made it more familiar.

“I shall not waste words.” Thus he began. “I have been a strong man, but that day is over. I can even foresee my end. But it is not of that I wish to speak now. Quenton—”

It was the first time he had used this name in addressing me and I greeted it with a smile, recognizing immediately how it would not only prevent confusion in the household but give me here and elsewhere an individual standing.

He saw I was pleased and so spoke the name again but this time with a gravity which secured my earnest attention.

“Quenton, (I am glad you like the name) I will not ask you to excuse my abruptness. My condition demands it. Do you think you could ever love my daughter, your cousin Orpha?”

I was too amazed—too shaken in body and soul to answer him. This, within fifteen minutes of an experience which had sealed my emotions from all thought of love save for the one woman who had awakened my indifferent nature to the real meaning of love. An hour before, my heart would have leaped at the question. Now it was cold and unresponsive as stone.

“You do not answer.”

It was not harshly said but very anxiously.

“I—I thought,” was my feeble reply, “that Edgar, my cousin, was to have that happiness. That this dance—this ball—was in celebration of an engagement between them. Surely I was given to understand this.”

“By him?”

I nodded; the room was whirling about me.

“Did he tell you like a man in love?”

I flushed. What a question from him to me! How could I answer it? I had no objection now to Edgar marrying her; but how could I be true to my uncle or to myself, and answer this question affirmatively.

“Your countenance speaks for you,” he declared, and dropped the subject with the remark, “There will be no such announcement to-night. If Edgar’s hopes appear to stand in the way of any you might naturally cherish, you may eliminate them from your thoughts. And so I ask again, do you think you could love my Orpha; really love her for herself and not for her fortune? Love her as if she were the one woman in the world for you?”

He had grown easier; the flush and sparkle of health were returning to his countenance. It smote my heart to say him nay; yet how could I be worthy of her if I misled him for an instant in so important a matter.

“Uncle,” I cried, “you forget that I have never seen my cousin Orpha, But even if I had and found her to be all that the most exacting heart could desire, I could not give her my love; for that has gone out to another—and irrevocably if I know my own nature.”

He laughed, snapping his finger and thumb, in his recovered spirits. “That,” he sung out, “for any other love when you have once seen Orpha! I had forgotten that I kept her from you when you were here before. You see I am not the man I was. But I may find myself again if—”

He paused, tried to rise, a strange light suddenly illuminating his countenance. “Come with me,” he said, taking the arm I hastened to hold out to him.

Steadying myself, for I quickly divined his purpose, I led him toward the door he had indicated by a quick gesture. It was that of his so-called den from which I had always been excluded—the small room opening off his larger one, containing, as I had been told, Orpha’s portrait.

“So,” thought I to myself, “shut from me when my heart was free to love, to be shown now when all my being is filled with another.” It was the beginning of a series of ironies which, while I recognized them as such, did not cause me a moment of indecision. No, though his laugh was yet ringing in my ears.

“Open,” he cried, as we reached the door. “But wait. Go back and put out all the lights. I can stand alone. And now,” as I did his bidding, marveling at the strength of his purpose which did not shun a theatrical effect to insure its success, “return and give me your hand that I may lead you to the spot where I wish you to stand.”

What could I do but obey? Tremulous with sympathy, but resolved, as before, not to succumb to the allurement he was evidently preparing for me, I yielded myself to his wishes and let him put me where he would in the darkness of that small chamber. A click and—

You have guessed it. In the sudden burst of light, I saw before me in glorious portraiture the vision of her with whom my mind was filled.

The idol of my thoughts was she, whose father had just asked me if I could love her enough to marry her.

Chapter 7

I had never until now considered myself as a man of sentiment. Indeed, a few hours before I would have scoffed at the thought that any surprise, however dear, could have occasioned in me a display of emotion.

But that moment was too much for me. As the face and form of her whom to see was to love, started into view before me with a vividness almost of a living presence, springs were touched within my breast which I had never known existed there, and my eyes moistened and my heart leapt in thankfulness that the appeal of so exquisite a womanhood had found response in my indifferent nature.

For in the portrait there was to be seen a sweetness drawn from deeper sources than that which had bewitched me in the smile of the dancer: a richness of promise in pose and look which satisfied the reason as well as charmed the eye. I had not done ill in choosing such a one as this to lavish love upon.

“Ha, my boy, what did I say?” The words came from my uncle and I felt the pressure of his hand on my arm. “This is no common admiration I see; it is something deeper, bigger. So you have forgotten the other already? My little girl has put out all lesser lights.”

“There is no other. She is the one, she only.”

And I told him my story.

He listened, gaining strength with every word I uttered.

“So for a mere hope which might never have developed, you were ready to give up a fortune,” was all he said.