1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

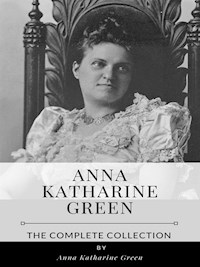

In 'Miss Hurd: An Enigma,' Anna Katharine Green masterfully intertwines elements of mystery and psychological depth, crafting a narrative that challenges the reader'Äôs perception of identity and moral complexity. Set against the backdrop of late 19th-century America, the novel examines the enigmatic character of Miss Hurd, whose layered persona unfolds through a series of compelling revelations that question the nature of truth and deception. Green's meticulous attention to detail and her innovative narrative style elevate this work, distinguishing it within the early detective fiction genre, as she blends traditional whodunit elements with a profound exploration of empathy and societal expectation. Anna Katharine Green, often hailed as the mother of American detective fiction, significantly shaped the genre with her pioneering focus on forensic science and psychological realism. Her academic background in literature and law offered her unique insights into the human psyche and legal intricacies, which undoubtedly informed her character development and plot construction in 'Miss Hurd.' Drawing from her own experiences and societal observations of the period, Green adeptly critiques the roles and perceptions of women in a patriarchal society, making her work both innovative and socially relevant. I recommend 'Miss Hurd: An Enigma' to readers seeking a profound literary experience that transcends mere mystery. Green'Äôs intricate plotting, combined with her rich character studies and social commentary, invites readers to delve deep into the motivations behind human behavior. This novel is not just a detective story; it is an exploration of the enigmatic nature of identity itself, making it a rewarding read for both mystery enthusiasts and literary scholars alike.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

Miss Hurd: An Enigma

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 My Arrival

“ ’T is a finely toned, picturesque, sunshiny place Recalling a dozen old stories.”

I have a story to tell. The story of a strange, impenetrable, fascinating woman; a woman in whose mysterious destiny my own has become seriously involved.

I saw her first at Beech Grove, the country seat of Edward Livermore. I had gone there at the suggestion of Tom Gaylord, and under the influence of the following letter:

“If you want a model for the Antigone you are said to be working upon, take a trip into the wilds about Cooperstown, and spend two days with Ed. Livermore. I saw a girl in his drawing-room a week ago, whose face is a living exponent of human passion at its loftiest and most commanding heights. Perpetuated in marble, it would make the fame of such men as you and I.

“Do not delay, or I shall be tempted to steal it for my Clytemnestra.”

It was late in the afternoon when I arrived in O— after a long day’s journey on the cars, and a carriage ride of some two miles or so through the beautiful scenery of this highly cultivated and picturesque region.

When we reached the town, I found that it began and ended in one long street, running between wooded slopes; and when I stopped at my friend’s door I was surprised to discover that the low and lengthy front of his old-fashioned house stood almost on line with the sidewalk, thus losing, to all outward appearance, most of the attractions usually to be found in the country-seats of wealthy New Yorkers.

But the door once passed, and the hall entered, my artistic nature was at once satisfied, and my imagination roused by the agreeable nature of the background against which this old mansion had been reared.

Through the wide doors and broad, latticed windows that opened directly opposite the entrance, I saw huge boughs of interbranching pine and beech, crowding up so close to the house that the whole appearance was that of some marvellous landscape let into the wall for the delectation of the entering guest; and, upon stepping nearer, my ears were charmed with the music of a babbling brook which ran by the doorstep on its way to the lake below. A pretty rustic bridge connected the threshold with the woods beyond, marking the beginning of a path that was destined to be the scene of more than one surprising encounter in the troublous four days before me.

Interested as we all are in the unexpected, I stood contemplating the great forest that thus limited my outlook, when a gush of youthful voices drew my attention inwards. Hastily turning, I encountered a bevy of young women who had entered the hall from one of the many large apartments on either side. Instantly I remembered the letter in my pocket, and the errand on which I had come.

A tall and dignified blonde was first presented to my notice. She was Mr. Livermore’s niece, and her name was Dalrymple. I thought her beautiful, but I did not see in her fine but conventional countenance any of the passion or grief of the immortal Antigone.

Nor could I perceive in the laughing-eyed Miss Tewksbury, who accompanied her, anything beyond a merry every-day sort of girl, whose attractions might serve to while away a pleasant half hour, but which were scarcely of a nature to inspire an artist, or to awake the imagination of the most prosaic worker in clay and marble.

Dainty Miss Clayton presented a more suggestive figure, but she was far from being the grand and impressive woman described by the enthusiastic Gaylord; so that I was presently convinced that in none of the group thus prematurely brought to my notice had chance favored me with a view of the extraordinary person for whom my journey had been made.

But when summoned to dinner I found myself seated in full position for observing the faces of all the assembled guests, I naturally expected some special reward for my scrutiny. But I was again disappointed. Not a face suggested passion, not a form inspired enthusiasm; and yet there was more than one beautiful girl present; and had I been seeking a model for any lesser creation than the daughter of Oedipus, I might have detected in Miss Clayton’s merry glance and dimpled smile sweetness enough to have beguiled me into an interest which would not have ended in heart-break and confusion.

It was the custom in this hospitable mansion for the various guests to collect at evening in a certain long drawing-room, which, from its connection with a small music-parlor, allowed the piano to be played without directly interfering with conversation.

In this room I therefore presently found myself, and as I am no smoker I had my little hour with the ladies before the gentlemen came in.

But though I enjoyed the mingled sparkle and sarcasm of Miss Dalrymple’s society talk, and was not altogether insensible to the flashes of repartee which kept Miss Clayton’s dimples coming and going, I own that under my apparent interest there lurked an uneasy sense of expectancy which led my eyes to travel more often in the direction of the door than the claims of the ladies present seemed to warrant. Did I look for some new entrance, and was it possible that I still cherished hopes of encountering the anticipated face, even after I had seen that the table was full and that no absent guest was mentioned?

The entrance of the gentlemen at eight o’clock definitely ended any such expectation on my part; and dismissing Gaylord from my thoughts with one low exclamation against the trick he had undoubtedly played me, I allowed myself to forget the hopes he had called up, and gave myself quite unreservedly to the amusements of the evening.

Of these, I shall speak of but one.

Chapter 2A Strange Visitor

“Woman—the morning-star of infancy, the day-star of manhood, the evening-star of age; bless our stars! and may they always be kept at telescopic distance.”

A certain Mr. Lillie had just received a letter of extraordinary interest, and he offered to read it for the general entertainment. It was from a college friend, and contained the details of a curious episode which had occurred to the writer on a late visit to his mother.

The letter ran thus:

“We live in a small but comfortable farm-house, some miles from Q— station. My mother, who has old-fashioned notions about work, keeps no girl, and when I am with her, as I invariably make a point of being in the summer vacation, she is glad to avail herself of any chance help that may offer itself, and often accepts the services of a neighbor’s daughter, which at other times of the year she would resent as an interference. This year she could not get even that, and I was about to cut my visit short, in consideration of her growing feebleness, when one morning there appeared at our door a young woman, who, by signs such as I have seen made by deaf-mutes, seemed to intimate that she wished to enter. My mother, who is naturally of a kind disposition, beckoned her in, notwithstanding her sensations of awe at the intruder’s manifest infirmity and her far from reassuring appearance.

“I was in the house at the time and saw her before she sat down, so I can tell you exactly how she looked. She was a woman of the most forcible appearance, and seemed totally out of place in the home-spun and ill-fitting garments in which she was clothed. Her figure, which was tall, exacted respect, and her face, for all its worn and tired look, possessed a certain beauty, which was the result of expression rather than feature; but she carried herself too stiffly for grace, and disfigured a countenance which stood in sad need of softening, by an arrangement of hair which added to the severity of her aspect and made her seem a woman of forty, though by other signs she could not have been more than twenty-five.

“At sight of me a line of perplexity or chagrin appeared on her forehead. She turned towards the door and seemed about to take an abrupt departure, but immediately changed her mind and faced about again.

“Surveying my mother with a forced smile, she dropped a deep curtsey which finished the quaint picture she presented, and made me her slave from that moment on, till—. But I will not anticipate by a word the development of the strange events which followed the appearance of this odd person at our door.

“My mother—. But first I must tell you that, after having in this manner expressed her respect and the obligation which she felt as a self-constituted guest, this strange anomaly of a woman sat down, and laying aside the small hand-bag she carried, began to take off her hat and shawl, with a decision and purpose which announced more plainly than words, that she had come to stay.

“My mother, after having cast me a doubtful look in which surprise was mingled not unnaturally with curiosity, promptly accepted the situation, and asked the stranger if she could hear what was said to her.

“The young woman nodded, but in a reticent way as if she almost resented the question, and having by this time relieved herself of her outside wraps, she deliberately opened her bag and took out a piece of sewing, upon which she began to work.

“My mother was so startled that she sank into a chair, and for a moment eyed her strange visitor with astonishment not unmixed with fear. But another glance at the plain dress, and neat, if unbecoming bands of dark hair, seemed to reassure her, and she observed quite composedly:

“ ‘You wish to stay with me to-day? Cannot you tell me what your name is?’

“A severe look from two as inscrutable eyes as it was ever my lot to encounter, answered this mingled question and appeal. Leaning forward, she took up her hat and shawl which she had laid upon the table, and for an instant we thought she was about to show her resentment at being questioned, by leaving us in good earnest. But instead of this she commenced to deliberately fold the shawl and place it on a high cupboard that stood near; after which she put her hat neatly away on the top of the shawl, and turning again, dropped another curtsey still more respectful than the last, and sitting down in her former seat, resumed her work. And that was her answer to my mother’s inquiry.

“Delighted, for my part, by a display of eccentricities that promised me enough amusement to make the somewhat gloomy day interesting, I now stepped forward and casually remarked:

“ ‘The clouds threaten thunder. We shall have a severe storm before night. If you have any distance to go, it would be better to start before it grows too late to make walking on the highroad dangerous.’

“She did not move.

“ ‘She intends to remain all night,’ I intimated to my mother, wishing that our visitor was as deaf as she was dumb.

“My mother, to whom the same conclusion had presented itself, shrugged her shoulders, and cast a glance which I was not slow to follow, at her visitor’s busy hands. They were thin but white, and bore but little evidence of having ever done any harder work than sewing.

“ ‘I need some one to help me in the kitchen,’ suggested my mother. ‘Are you accustomed to wash dishes, and can you sweep and cook?’

“Instantly and without giving the least hint of displeasure, she rose, put her work away in her small bag, and began to move towards the kitchen door, which stood wide open.

“ ‘Ah!’ nodded my mother, as if enlightened at last as to the purposes of her strange visitor. But I, who had seen much of women, thought my mother was a little premature in thus judging of the intentions of a person who had a face like a sphinx and wore her dress like a scarecrow. However, I said nothing, and watched my mother disappear into the kitchen, with a decided sensation of expectancy which would not allow me to leave the sitting-room.

“It was now about five o’clock, the hour at which my mother usually put on her tea-kettle. So, making the excuse to myself that the pail from which she drew her supply of fresh water, was in all probability exhausted I sauntered into the kitchen to get it. My mother was not there, and for a moment I thought the room empty, but by the time I had reached the bench where the pail was kept, a movement in a certain dim corner attracted my attention, and I perceived our new servant, or guest, or whatever you may choose to call her, standing in an attitude of such extraordinary agitation and defiance, that I irresistibly followed the direction of her gaze, and found that it was fixed on a wagon that was approaching down the road. She was so absorbed that she neither noted my presence nor caught the gesture of astonishment with which I recognized the change which had taken place in her. From a stiff, automaton-like creature, she had become a living woman, of a rare and extraordinary type. Power breathed in her dilated nostrils, and determination from her fixed and flashing eyes. Even the lips, which she had kept demurely pressed together in the most rigid of all lines, now stood apart, scarlet and palpitating, and if the opportunity of observing her had but lasted an instant longer, I am sure that I should have been able to read the secret of her emotion and solve the mystery of her behavior.

“But scarcely had I taken in her full appearance than her lips closed, her bosom sank, and her eyes recovered their look of stony indifference. She turned again toward the stove, and began to lift off the covers in a dazed way, which showed that, though the cause for her emotion had vanished, she had not yet recovered from the tumult of feeling into which she had been thrown.

“Just then my mother stepped into the room from the pantry, and I seized the bucket, and hurried out of the backdoor, anxious, if possible, to catch another glimpse of the wagon which had occasioned so much emotion in this stranger. It was just disappearing round the house, but, in the instantaneous glimpse I caught of it, I saw that it held two men, one of whom wore a high hat.

“When I re-entered the kitchen, I found her laughing,—not loudly or as if in response to any remark which my mother had made, but low and to herself, as if she felt the reaction following some danger averted or some scandal escaped.

“ ‘She is here as a refugee,’ thought I, ‘and fears pursuit. Shall I alarm my mother with what I have seen, or shall I keep still and confine myself to keeping the girl closely under my eye.’ I decided, rightfully or wrongfully, upon the latter course, and, going back to the sitting-room, sat down in full sight of the kitchen door.

“Presently I heard words, and then a crash of breaking china. As the words were in my mother’s voice, and the crash evidently not a serious one, I did not move, and presently was rewarded for my self-control by seeing the form of my mother in the open doorway, with the two pieces of a broken plate in her hand, and on her face a doleful look that made me laugh in spite of myself.

“ ‘She does not know the least thing about housekeeping,’ she began, with a glance of righteous anger at the pieces she held. ‘She cannot even light a fire; and as for mixing biscuit—’

“ ‘Never mind,’ said I. ‘Give her some of your sewing, and take me in as an apprentice. I shall not make any more mischief than she has done.’

“ ‘But what did she come here for?’ my mother asked. ‘I do not keep a hotel. The fact of her being dumb should not make her presumptuous. I declare, I believe I will go back and make her explain herself. There is some mystery about her, I am sure. Did you notice what eyes she has, and how near she comes to looking like a lady when she moves or smiles?’

“ ‘If I am not mistaken, she is a lady,’ I answered; ‘but a lady you should not trust too much. We will keep her to-night; but to-morrow—’

“ ‘She shall go,’ finished my mother, emphatically. ‘I want no one under my roof whom I cannot understand. I wonder if she can write?’

“ ‘Why?’ I asked.

“ ‘Because, if she can, she shall tell me what her name is. Why, think of it—I do not know what to call her! I have to say, “Here, miss!” as if I were the servant and she the mistress.’

“It was awkward, and I could not help smiling. But we could go no further, for just then the subject of our conversation appeared before us with a teacup in one hand and the handle of it in the other. Shaking her head, she laid them both gravely in my mother’s outstretched palm, and, without any further intimation of her regret, passed at once to the table where she had left her bag, and placing her finger on it, smiled resolutely upon my mother.

“ ‘She means that she is unfit for kitchen-work and prefers to sew,’ I remarked, in explanation of her action. ‘Is not that it?’ I asked, addressing her for the second time.

“She made the inevitable curtsey which seemed to be her favorite way of expressing acquiescence, and then nodded, sitting as she did so.

“ ‘I have no sewing,’ observed my mother, shortly, and went back alone to complete her preparations for supper.

“I looked at the young woman—or was she old, much older than I had thought,—and a strange sensation seized me. Was she the stranger I had considered her, or was she a person once well known to me in some dim and hazy experience of the past, or in some dream-world where figures strange as she evolve themselves from nothing, as she had seemed to do, and vanish into nothing, as she was more than likely to do? I felt that her eyes were familiar, her mouth, the curve of her cheek, and the nameless something which bespeaks personality. And yet I did not know her, and found no picture in all the gallery of my past life to which she corresponded. Was I living over some experience of a former existence? or had I become so imbued by her presence, odd as it was, that she already seemed to have a fixed hold upon my mind which made her in some way unnaturally familiar?

“Brooding over this problem I forgot to speak to her, but she did not seem to resent it. Perhaps, being dumb, she did not expect the ordinary attentions of social intercourse.

“At all events she showed no embarrassment till I remembered myself and began to talk, when she immediately grew restless, and looked about for something wherewith to occupy herself.

“As I did not wish to give her an opportunity of evading my eye, I did not lend her my assistance in this search but pressed question after question upon her till I thought she must answer one of them from very shame. But I did not know her. Instead of growing nervous under this attack, she seemed to become calmer and more at her ease; and when, at the end of my resources, I pushed a pencil and a bit of paper towards her, saying, ‘Perhaps you will kindly write who you are.’ She rose, and meeting me eye to eye, with a steady, sane look of respectful reproof, walked to the cupboard and began taking down her hat and shawl.

“At this sight I was seized with compunction and felt that I could not let her go at so late an hour, especially as at that moment a low rumble of thunder was heard in the west, where the clouds lay piled up in a way that betokened a storm of no little violence.

“ ‘It is going to rain,’ I protested, ‘You cannot leave the house now. Sit down and I will ask you no more questions.’

“She immediately restored her shawl to its place and took off her bonnet.

“ ‘I will bring you a book,’ said I.

“But though I handed her two or more fresh volumes of decided interest, she made no attempt to open them, but seemed to prefer to sit with her eyes on the clouds, which had now assumed a brazen aspect.

“As for myself I was satisfied to sit and watch, her, and strive to penetrate the meaning of the shifting expressions which now began to permeate a countenance which, saving that passing moment in the kitchen, had hitherto been but a mask. Was it intellect which gave that flash to her eye, was it feeling that quivered in the corners of her lips when the thunder suddenly roared and the lightning darted down? I thought at first that it might be intellect gone astray and feeling carried to the verge of fear; but I was soon undeceived when, in the midst of a most appalling bolt, she rose and passed to the window, and with a calm and almost exalted expression, raised her face towards the sky as if she felt a kinship with the raging storm which forced her to throw aside her reserve and show herself for the powerful creature that she was.

“ ‘She will be struck!’ shouted my mother, advancing from the kitchen. But the lightning flashed downward and was gone, and our strange visitor still stood before us, formidable in her very silence.

“She sat down with us at supper, and her manners were those of a lady. My mother, whom I had succeeded in acquainting with my failure to make this interesting intruder talk, was kind in her attentions, but no longer inquisitive or loquacious. Indeed the meal began and ended in almost undisturbed silence, and when the evening bade fair to pass in the same uninteresting way, my mother, with happy heed to her self-constituted guest’s evident fatigue, offered to accompany her to her room.

“With the first real smile we had seen on her face, the stranger rose, and, taking up her bag, followed my mother with cheerful alacrity. Indeed, her gratitude made her quite beautiful, and when in passing me she paused to bestow that quaint little curtsey which seemed her only mode of expression, I experienced a certain thrill of sympathy for her, which was as much the result of admiration as compassion.

“When my mother returned alone, I surveyed her inquiringly. Had the woman, when released from the constraint imposed by a man’s presence, become in any way more communicative? Evidently not; for my mother hastened to say:

“ ‘If ever a woman was tired, that woman is. Do you know, I think she threw herself on the bed the moment I left the room!’

“ ‘Without undressing herself?’

“ ‘Without undressing herself.’

“ ‘Have you locked the door?’ I queried. ‘I should feel more comfortable if I thought she was well shut in for the night.’

“ ‘Would you? Well, that is strange,’ rejoined my mother. ‘I feel the same way, and told her that I should take the liberty of fastening the door upon her.’

“ ‘And what did she say to that?’

“ ‘Why, nothing; she is dumb or pretends to be so. But she showed no resentment; on the contrary she smiled and nodded her head as if quite satisfied.’

“ ‘An inexplicable creature,’ I ventured.

“ ‘And one that shall not stay in my house two hours after breakfast.’

“As this decision seemed to be one that I could not in wisdom combat, I silently accepted it, and retired to my own rest with the expectation of seeing the shawl and bonnet and shabby little bag disappear from our inhospitable doors the first thing in the morning. But when after a somewhat broken sleep I came down into the sitting-room at nine o’clock, it was to see the shawl and bonnet in their old place on the cupboard, and their possessor in the same chair she had occupied the night before, diligently sewing a long seam in a piece of work so large it could never have come out of the little bag.

“ ‘I cannot push her out of the door,’ explained my mother, as I hastily entered the kitchen with inquiry in my face. ‘And I shall have to push her, if she goes,’ the dear old lady continued, with a deprecating smile, ‘for she certainly will never leave the house of her own accord.’

“ ‘You are worried by her,’ I observed, noting that the smile was not without its nervousness.

“ ‘No,’ answered my mother, ‘and yet her manners might certainly be more reassuring.’

“I agreed with her and went back to the sitting-room.

“ ‘I am going into town,’ I remarked, stepping squarely up before the stranger, and speaking as gently and as firmly as my sympathies would allow. ‘If you will be ready in half an hour I will take you with me. You cannot stop here, you know; my mother has not strength enough to entertain two guests.’

“She flushed, raised her extraordinary eyes one moment towards mine, and then carefully folding up her work, laid it on the table and proceeded to put on her shawl and hat.

“More daunted by her manner than by the action itself, I begged her not to hurry herself, but she neither desisted nor gave the least token of hearing me. When she was dressed in her outside wraps she sat down and I soon recognized that there was nothing for me to do but to follow her example and prepare for departure. I accordingly went into the kitchen, and after drinking a cup of coffee, harnessed up the poor old horse which my mother uses for such occasions, and driving around to the front door I waited for our guest to come out.

“But she did not come, so, leaving the horse standing, I went in, and found her sitting in the same attitude in which I had left her. I told her the team was ready and offered her my arm. She stared at it, then at me, and slowly rose. Moving towards the door, she went out, and then catching a glimpse of my mother in one of the windows, dropped a final curtsey before stepping into the wagon. It was her last expression of good-will. All the long way to the village she maintained not only perfect silence, which was to be expected of her, but a rigid immobility, that awakened in me a species of awe.

“I was glad when I reached the village. Fascinated as I was by her peculiarities, I could not but feel the oppression of her presence. When, therefore, the white steeples of the churches became visible, I said to her, in the same quiet tone I had before used:

“ ‘There is the town; is there any particular place to which you would like to be driven?’

“I did not expect a reply, and was therefore correspondingly surprised when she turned her head and slowly shook it.

“ ‘Shall I leave you in the big square before the church?’ I pursued.

“But for this she had no answer, and I was forced to drive on, in a guilty frame of mind, not knowing if I were acting a humanitarian’s part in thus setting adrift this poor waif, who either did not know her own mind or, knowing it, lacked the means of communicating it. But another look at her strong, refined face, with its lines of mingled suffering and thought, convinced me that her peculiarities had their source more in wilfulness than inconsequence, and while under the sway of this idea, I drew my horse and politely held out my hand to aid her in alighting.

“ ‘I hope that you have friends here,’ I ventured, feeling a strange thrill as her hand closed over mine.

“Her reply was a commanding gesture for me to drive on, and so sudden was the change in her, from meek acceptance of my wishes to a distinct expression of her own, that I unconsciously obeyed her and moved slowly down the street, leaving her standing in the public square.

“When I reached the corner I looked back; she had not moved; but when a few paces on I turned again, she had disappeared entirely from my view, nor did I see her again, though in my interest and anxiety I drove up and down the street several times.

“I did not return home till afternoon. I had errands to do for mother and one or more friends to visit. Perhaps I had some vague idea of hearing something about this mysterious woman at some of the houses I visited, but if any such motive lay at the bottom of the various calls I made, it was not destined to be rewarded, for no one that I met had ever heard of such a woman, much less seen her. At three o’clock I turned towards home, and at four drove into the yard. Can you imagine my surprise at beholding on the door-step the tall, awkwardly clad form of our late guest, waiting with her little bag in her hand for the door to open, just as she had done the day before, though with even greater signs of weakness and fatigue apparent in her bearing.

“She had walked all the way back from the village; and thus ended my first effort at casting her off.

Chapter 3 A Strange Departure

“The heart has reasons that reason does not know.”

“Well, we took her in; how could we help it? Though she was a strong woman, it was evident from the dark rings under her eyes that her physical powers were about exhausted; while her look and smile, both too tremulous to be forced, had an eloquence in them which my mother, as well as myself, found it impossible to resist.

“ ‘We will keep her one more night,’ decided the former; ‘but to-morrow you must take her to Y— and put her into the hands of Dr. Carter.’

“Y— was ten miles away, and Dr. Carter was a well known philanthropist of the place.

“Accordingly next morning I took her to Y—, where I gave her into the hands of this good clergyman, who promised to make inquiries in her regard and restore her if possible to her friends. But when I had left my charge behind me, and returned again to my mother’s house, I felt strangely uneasy and found it hard to interest myself in any of my usual pursuits. My mother, too, seemed restless, and interrupted her work more than once to step into the sitting-room and ask me some question about my ride. And yet it was a relief to us both to sit down by the evening lamp without the consciousness of that silent presence in our midst, and, when we finally bade each other good-night, it was with a cheerfulness we had neither shown nor felt during the two previous evenings.

“Imagine then my sensations when, upon entering the room at the usual hour in the morning, I again saw lying on the cupboard the cheap shawl and tawdry hat which I had supposed vanished from that spot forever. Had our self-constituted guest come back while I had been sleeping and was she even then under our roof? Hastening into the kitchen, I questioned my mother, and she, half smiling, half frowning, remarked apologetically:

“ ‘She arrived not two minutes after you went upstairs. If she had dropped at the door I should not have been surprised, so exhausted did she look and so incapable of standing. She is in her room now; I thought I would let her sleep till breakfast was ready.’

“ ‘We shall have to go ourselves, if we wish to get rid of her,’ said I. ‘What do you suppose she would do if left in undisputed possession of the house.’

“My mother laughed, but I was more than half in earnest, and I do not know to what lengths I might have been led, in my endeavor to shake ourselves loose of our fascinating but somewhat oppressive guest, if events had not presently occurred that made any action on my part unnecessary.

“We had finished breakfast, and our silent guest was engaged in sewing, with a wonderfully contented and happy look on her face, when I suddenly beheld her start to her feet and assume an expression that startled, if it did not alarm me. At the same minute a wagon drove up in front of the door, and I had barely time to observe that it contained a gentleman with a tall hat, when she flew from her place in the window, and with gesticulations of fright and entreaty, rushed into my mother’s bedroom and violently closed the door.

“The sound it made mingled with the knock that at this moment resounded from without, and stepping to the front door I opened it just as my mother came in from the kitchen,

“The gentleman who confronted us was sufficiently good-looking to merit attention, and he had the bearing, as well as the garb, of a city-bred man of some pretensions. Yet I did not know whether to like him or not, and was rather guarded in my greeting.

“He on the contrary was affable and made his inquiries in a tone of the utmost consideration and respect.

“ ‘I am looking,’ said he, ‘for a young woman who has inconsiderately left her home and friends, and who, I am told, has at present taken refuge with you. Have you not such a person here, and is not this her hat and shawl which I see?’

“ ‘There is a woman here who seems dumb,’ returned my mother, rapidly advancing. ‘She came to the house some two days ago; we find it inconvenient to keep her, and I am very glad to see any friend of hers who will take her away and treat her kindly. Are you her relative or—or—’

“ ‘She belongs to me,’ he declared, peering deprecatingly about for signs of the presence he sought.

“ ‘I will call her,’ said my mother.

“But I felt some doubts as to his intentions, and hastened to interpose.

“I fear she will not want to go with you,’ I objected ‘and I should not like to give her up against her will.’

“ ‘Oh,’ he asserted with the utmost confidence, ‘she will not refuse to go with me. Only bring us face to face, and you will soon see that I have complete influence over her.’

“Still doubtful, but not seeing how I could refuse him the interview he asked, I stepped to my mother’s bedroom door and opened it. Great God, what a picture greeted my eyes!

“Drawn up in the remotest corner in an attitude appalling to behold, I discerned the figure of our strange guest. She had caught up a stick of rough wood from the neighboring fireplace and now stood with it brandished high over her head, in an attitude of threat and defiance which was almost titanic in its suggestion of concentrated power and passion.

“My mother shrieked, but the gentleman against whom this menace seemed to be directed, calmly pushing his way in, uttered one word of whispered command and entreaty, and the rigid arm dropped, the blazing eyes fell, and the gleam of desperation, which had lent such force and splendor to her face, faded like a light that is blown out, and she came forward, dropping the stick from her inert hand.

“ ‘Will you go with me?’ he asked quietly and kindly, surveying her with manifest compassion, and yet with a determination that proved the extent of his control both over himself and her.

“She bowed her head, and heaving a deep sigh, passed us both with a little curtsey, and went directly to the cupboard. He did not offer to help her, but stood by with knitted brows, while she tied on the shabby little bonnet so out of keeping with her grand head, and wrapped about her shoulders, the precise shawl which added twenty years to her age and made her, when completely dressed, look like some respectable maiden lady, with a limited experience of life.

“I felt a pang of regret as he put on his own hat and made a motion for her to depart. My mother, meeting my eye, made a significant gesture, and obeying it, I followed them out to the wagon, where I stopped him as he was about to unhitch his horse.

“ ‘Are you,’ I whispered, approaching closely to his ear, ‘her keeper?’

“He turned upon me with an indignant gesture.

“ ‘She is not mad,’ he declared. And unfastening the hitching-strap, he jumped into the wagon.

“ ‘Then you have hypnotized her!’ I cried. ‘She shall not go with you unless you tell me—’

“ ‘I have not hypnotized her!’ he protested. ‘Would to God I had the power to do so!’ And seizing his whip, he gave a clip to the horse, which started forward on a jump down the road.

“This time she did not come back, and I have been asking myself ever since, what was the secret of her peculiarities and the cause of her terrible antagonism to a man whom she nevertheless acknowledged to be her master, and followed without any apparent demur.”

Chapter 4 The Ministering Sister

“Why seek at once to dive into The depths of all that meets your view?”Goethe

“Is that all?” cried a voice.

“Yes, that’s all. Interesting, isn’t it?”

“Do you know,” spake up another voice, “that it makes me think of an experience my sister Caroline once had. It was not of the same kind, of course, and the people were very different, and all that, but the woman showed the same fear and antipathy to a man, and—well, it was all very curious, and—”

“Hear! hear!” exclaimed more than one of the young people present.

“Do you want the story?”

“Hear! hear!” was again the cry.

The speaker, who was a slim young man of somewhat whimsical turn of countenance, and who had been introduced to me at table as Mr. Parke, came slowly forward at this, and, waiting for no further encouragement, began at once to relate the following.