15,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

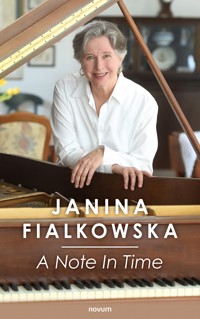

- Herausgeber: novum premium Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

When 12-year-old Janina Fialkowska momentously decided to dedicate her life to music, little did she know what was in store. Certainly her love of music and desire to share this love provided fulfilment and joy, and there was a certain glamour to the life of a touring artist. She traveled to many countries, met many fascinating people, and indulged her weakness for good food. But there was another side to such a life, and reality made its ugly appearance fairly early on. This collection of autobiographical anecdotes, some poignant, some hilarious, describes her meeting with the legendary Arthur Rubinstein who subsequently shaped the course of her career, her colourful adventures as a young North American woman in the male-dominated music world and her final triumph over horrific illness.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 634

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Contents

Imprint

Dedication

For Harry 4

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

Whirlwinds of Snow (“Chasse Neige”) by Franz Liszt 6

Chapter 2

Scenes from Childhood (“Kinderszenen”) by Robert Schumann 21

Chapter 3

The Sounds and the Scents (“Les sons et les parfums”) by Claude Debussy 53

Chapter 4

A Maiden’s Wish (“Zycenie”) by Frédéric Chopin 66

Chapter 5

Invitation to the Dance (“Aufforderung zum Tanz”) by Carl Maria von Weber 73

Chapter 6

All Was Created by Him (“Par Lui tout a été fait”) by Oliver Messiaen 98

Chapter 7

Nights in the Gardens of Spain (“Noches in los jardines d’Espagna”) by Manuel de Falla 128

Chapter 8

“Marche funèbre” from the B flat minor Sonata by Frédéric Chopin 150

Chapter 9

Concerto in the Italian style (“Concerto nach italiänischen Gusto”) by J.S. Bach 183

Chapter 10

Dances of the companions of David (“Davidsbündler Tänze”) by Robert Schumann 202

Chapter 11

“Everything Waits for the Lilacs” by John Burge 232

Chapter 12

“Navarra” by Isaac Albéniz 258

Chapter 13

Variations on “Rule Britannia” by Ludwig van Beethoven 271

Chapter 14

Mazurka: Our Time (“Notre temps”) by Frédéric Chopin 302

Chapter 15

“Remembrances” (“Efterklang”) by Edvard Grieg 321

Epilogue

Dates to Remember

List of Photographs

Imprint

All rights of distribution, also through movies, radio and television, photomechanical reproduction, sound carrier, electronic medium and reprinting in excerpts are reserved.

© 2021 novum publishing

ISBN print edition: 978-3-903861-97-8

ISBN e-book: 978-3-903861-98-5

Editor: Ashleigh Brassfield, DipEdit

Cover images: Ulrich Wagner

Cover design, layout & typesetting:novum publishing

Images:Janina Fialkowska; p. 346: Sgt Joanne Stoeckl, Rideau Hall © OSGG, 2002

www.novum-publishing.co.uk

Dedication

For Harry

Acknowledgements

There have been a few friends who, with their memories, their enthusiasm, their patience and their expertise, have been of invaluable help in the writing of this book and I’d like to thank them all. I think the greatest debt of gratitude goes to Nicola Schaefer who read the book right after it was first written and convinced me it was of some value. Since then, she has never stopped pushing, prodding and providing motivation until it was finally finished and sent off to the publishers.

Others who played a vital role are Judith Rice Lesage who helped me with all the foreign translations, Lady Annabelle Weidenfeld, my brother Peter, my cousin Alison Hackney, John Pearce, Linn Rothstein, Flora Liebich, Elaine Plummer and Jeffrey Swann.

And many thanks to my friends Richard Sauer and Josefine Theiner who got tired of hearing about the book as it gathered dust on my studio shelf, and found a publisher for me: Novum Publishing and the excellent and thoughtful Bianca Bendra who has expertly guided me through the entire publishing process.

Finally I would like to thank my husband Harry; quite frankly, without him, there would be no book.

Chapter 1

Whirlwinds of Snow (“Chasse Neige”) by Franz Liszt

My eyelids flickered as I slowly drifted back into consciousness. A pale, sickly blue light filtered through my damp lashes and, bit by bit, I became aware of my surroundings. There was an unnatural stillness. Sounds were muffled, distant. I knew that I was in a hospital recovery room, and the realization that I was still alive caused a smile to cross my face before more complex thoughts were generated in my brain, dulled by anesthesia. There was a numbness in my left arm and the peaceful insouciance of a drug-induced state was soon dispelled when, in a sudden panic, I attempted to wriggle my fingers under the bedclothes. But all was well; they moved as before: pianist’s fingers. My heart continued to thud at an alarming rate and cold sweat spread across my forehead.

The world eventually shifted into focus; lights brightened, sounds amplified, and I remembered: this was a cancer hospital and I had just lost a chunk of my left arm. I could see that I was not alone in my predicament, which was somehow reassuring. That day there were many of us, lying in our cots in three tidy rows, waiting for the surgeons to deliver their verdicts. Some patients were still unconscious while others were surrounded by family members speaking in low, encouraging tones. There were those who, like myself, lay silently with a knot of anxiety growing within, and those who seemed to find delight in calling out loudly and repeatedly for the nurses, unable to cope for even a few seconds on their own. The cries of the few who were in extreme distress were heart-wrenching; I felt empathy, pity, but mostly fear in the presence of such suffering. In the bed next to me someone was moaning softly, but although I tried to turn my body around to see, I found I was more or less tied down and couldn’t budge. My left arm felt heavy and lifeless but, mercifully, I felt very little physical pain.

Nurses flitted efficiently from patient to patient, brightly cheerful, dealing briskly with the stress of a room vibrating with palpable anguish. The sounds of disembodied voices, machines beeping, curtains being pulled to and fro, wheels turning and oxygen pumping soon became exhausting. I was freezing cold and shivering so badly the bed was rattling. My body felt sticky and saturated with hospital stench, dried blood and disinfectant, and I had been pumped full of liquids during the procedure, so my bladder was constantly and painfully full and oh, how I loathed even the thought of bedpans! Also, like the sword of Damocles, the pending results of my biopsy hung perilously over me.

Presently a nurse, noting that I was awake, stopped by to ask how I felt. In a display of totally inappropriate fortitude, I reassured her that I felt fine when actually I felt quite dreadful, having suddenly been engulfed in waves of nausea. Minutes later I disgraced myself by being sick, mostly – although not completely – into the little basin conveniently stationed within reach.

From the clock on the wall opposite I calculated that I had already been in the hospital for nearly twelve hours. It was 6:00 pm on January 31st, which just happened to be Harry’s birthday. Sitting miserably in a hospital was not the way I had envisaged my newly acquired husband celebrating his birthday, but it seemed as though greater forces had seized control of our common destiny, altering the course of our lives and steering us into dangerous whirlpools and eddies.

Up until that day my life had been a seesaw of the glorious highs and desperate lows typical of a performing artist with a demanding schedule. Nevertheless, over the years both body and mind had received quite a battering, which I had ignored. I had managed to bounce along unchecked, riding on my innate stubbornness, basic good health, and a large dose of childish naivety.

This time, however, the events leading up to the biopsy had been simply too much even for a tough campaigner. The camel’s back was succumbing not to the proverbial straw, but to a giant bale of hay. As I waited for medical science to reveal the next phase of my life, my mind, in a futile attempt to disassociate itself from the present, harkened back not to a happier distant past but to the past year, starting with another birthday and another life and death drama that had occurred eight months previously.

We should have been celebrating my fiftieth birthday, but the day was spent in transit from Knoxville, Tennessee, where I had been playing on tour, to Montreal, where my mother had been rushed to the hospital. I spent the next two weeks at her bedside watching her die. She had a virulent form of leukemia and had developed bronchitis, a fatal combination. I learned a lot during those two weeks about courage and dignity, about unconditional love and about the incalculable power of a sense of humour. My mother showed no fear, was invariably courteous and accommodating to the overworked nurses, and made witty comments to try to lessen my concern and grief, right up until the moment she slipped into a final coma. She had taught me how to play the piano with honesty; she now taught me how to die with integrity.

Shortly after, at the beginning of June, Harry and I were married in a private ceremony held in the Bavarian village where he had grown up. It had required the written permission of the Highest Court of Bavaria and an onerous, transatlantic quest to assemble all the correct and pedantic documentation (not helped by the fact that, fifty years prior, the wine at my christening must have been flowing quite freely, as the officiating priest had misspelled both my father’s and my names on the baptismal certificate). Considering the death of my mother only weeks before and given that neither Harry nor I had ever wished for a huge wedding, only Harry’s mother and brother and a few of our closest friends were present. Everyone except me seemed to be shedding copious tears during the service. As for myself, I was intent on understanding what the nice lady registrar, who was marrying us, was saying. My comprehension of German was somewhat feeble at the time, and I was desperately trying not to say the wrong thing at the wrong time. However, in the end I managed a resounding “Ja.” at the appropriate moment, which was a colossal relief.

In the back of the room, Sena Jurinac, legendary star of the Vienna State Opera and one of Harry’s closest friends, commented in a clear stage-whisper that the registrar’s speech was unintelligible: no one seemed to know how to project their voices nowadays. The sobs now became punctuated by an occasional giggle.

Our wedding lunch was held, romantically, in the little country restaurant where Harry and I had had our first meal together alone.

There was no suggestion of a honeymoon due to time restraints. Instead, we had a weekend in the mountains at a delightful bed and breakfast, accompanied by three of our closest friends who had come from Northern Germany and California. It rained the entire time, but our party was merry, and I regretted having to go back to work on Monday.

Over the next three months I flew back and forth to Germany as often as possible between concerts in North America, trying to maintain some semblance of a normal married life. For years I had firmly maintained, both publicly and privately, that marriages and concert careers for women were incompatible. I was now determined to disprove my own theory. Being the spouse of a performing artist can be a thankless task; always tiptoeing around the neurotic spouse on concert days, making sure there are no disturbances, always playing the secondary role, the person in the background, the support, the nanny, as well as the lover, suffering right along with all the pre-concert anxieties but never having the opportunity to dispel the personal stress. The performer has the cathartic concert, the applause, the compliments, while the spouse continues to suffer long after the concert reception is over. Then there are the long separations – I didn’t know how we would manage, but I was determined our marriage would work.

Harry, who was running a “period instrument” festival in the Allgäu region of Germany, had a hard time getting away, so I did most of the travelling back across the Atlantic. He did, however, manage to escape for a weekend in July, when I performed the Paderewski concerto in the pouring rain during an outdoor concert in Quebec City for a sold-out crowd of umbrellas, followed by a wonderful memorial party for my mother in the old family home near Montreal. My brother and I celebrated her life with family and best friends showing old family movies dating back to the 1920s and consuming vast amounts of delicious food and champagne. It was a marvelous party; my mother would have loved it.

The next day I drove back to the States and Harry returned to Germany. I had a string of concerts to perform and a CD to record, which translated into over six hours a day practising hard at the keyboard. I never minded this kind of intensive work. In fact, I loved seeing the pieces slowly taking shape and reaching performance level. It’s a little rough on the body, but I had always been one of the lucky ones, never having suffered from the normal pianistic ailments of tendonitis, carpal-tunnel syndrome, or just plain old muscle strain.

By the end of August the concerts were over, the CD of Liszt Etudes was complete, and I slipped eagerly into my unaccustomed role of “Frau Intendant” or “Mrs. Director” throughout Harry’s festival. The “Klang&Raum” (Sound and Space) festival was Germany’s premier period instrument festival and had been administered and nurtured by Harry since its inception nine years previously. It was a unique blend of excellent concerts and recitals, all performed on historically accurate period instruments of the baroque and early classical eras. It was held in the church and in the adjoining seventeenth-century Benedictine monastery (now transmuted into a hotel/conference centre) of the picturesque village of Irsee in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps. Coincidentally, the festival’s orchestra in residence was the Canadian-based Tafelmusik, so at least half the orchestra members were people I already knew.

There were also marvelous meals, excursions through the lovely Allgäu countryside in horse-drawn carriages, and picnics in Alpine meadows. Harry, who had built the festival up from scratch, was on friendly terms with just about everyone who bought a ticket, and there was a family atmosphere that encompassed not only the public but the administration, the kitchen staff, the stage crews, the musicians, and the sponsors. People returned year after year from as far away as California and Japan.

But smooth-running, happy festivals don’t happen by themselves, and a price must be paid by someone. It was an intensive two weeks – rehearsals, then six days of performances with up to three concerts a day, intertwined with gourmet feasts, official dinners, sponsor events, lectures, and endless speeches. I loved it all – except for the speeches, which tended to drag on for hours, and the cocktail parties, where I attempted to converse wittily and intelligently in German. I took my role of “Frau Intendant” very seriously, but most likely failed miserably, since the art of small talk, even in my own English and French, eludes me totally.

The music, played on unfamiliar instruments and tuned in a way to which I was unaccustomed, sounded alien to me at first. But the performers were, for the most part, outstanding, and good music played at a high level will always stir the soul, whether the instrument is a Stradivarius or a tin whistle.

For a week we hardly slept, so that by the time the last good-byes were said and the final post-mortems were over, we were beat. I had two days before I had to fly back to the US for a cruel two-month separation. To have had the good fortune of finding the love of my life well into my middle years, only to be faced with the constant prospect of future separations, was hard to bear. In an attempt to alleviate the pain as best we could, we planned a brief trip to Paris, a city we both loved but had never visited together, for two nights before I continued on to New York. We were both so exhausted that jokingly we told all our friends that we were flying to Paris to take a nap. Which is exactly what happened – unintentionally. When we foolishly lay down on the bed after our arrival on a golden Parisian autumn day, we promptly fell asleep, losing the entire first afternoon.

Luckily the next day was also glorious and we decided to do all the touristy things that for years, as seasoned, snooty Francophiles, we had scorned. So, we climbed to the top of the Eiffel tower, drank tea and ate pastries in Montmartre, and rode the Bateau Mouche at sunset. It was a heavenly day; my first day of true relaxation since well before the death of my mother.

A few days later, on September 10th, I was in New York City for a meeting with my accountant and my financial advisor. The meeting wasn’t very taxing, and I didn’t have to fake looking interested or nodding in deep understanding when, in truth, I hadn’t a clue what they were talking about, which was normally the case; the hour passed very pleasantly.

The next morning was so beautiful and the sky so crystal clear and piercingly blue that Bill, my financial advisor, made the spontaneous decision to walk to work even though it would mean he arrived a bit later than usual. As he approached his office at the World Trade Centre, he saw a huge passenger jet crash into one of the twin towers. The Solomon Smith Barney building, where Bill’s office was located, was the third and last building to completely disintegrate as a result of the brutal attack on 9/11. In seconds, America the complacent was plunged into chaos.

The psychological impact of that day’s events was horrific and far-reaching. The fact that human beings could be driven, by whatever motives, to plan, execute, and rejoice over the murder of thousands using planes filled with live individuals as grotesque battering rams – and all this in the name of God – defies comprehension. But then, evil has always existed, and human nature has clearly not progressed since our days in caves. It is just that our methods of harming each other have been modernized, and 9/11 was a particularly shocking new twist on man’s moral depravity.

All day we were glued transfixed to our television screens, Harry in Germany, myself in our house in Connecticut. The pictures of devastation and destruction were replayed over and over again, forever branded in our memories.

Somehow, life had to continue, and it limped painfully along over the next few weeks. In spite of the turmoil, I had contracts to fulfill and concerts to play – with the considerable impediment caused by the temporary closure of all American airports. To get anywhere I either had to drive myself or find circuitous routes via Canada and Canadian airports. I managed to reach all the venues in time for the performances, but missed a few of the vital orchestral rehearsals – once with dire consequences, since putting together the massive Brahms D minor piano concerto in a small town with a good but secondary orchestra requires more than just a quick run-through before the concert. I was quite mortified by the flawed result, every bar a nightmare of insecurity, though there was a form of redemption when the concert was repeated the next day and Brahms was treated more honorably. The whole experience wore me out completely.

Even when US airports reopened, there was an atmosphere of hysterical paranoia everywhere, as new, oftentimes defective, security machines were being installed, and security personnel floundered. Passengers sweated and waited in the long, hot lines, unused to the removal of shoes and jackets for the airport scanners and to the unpacking and scrutinizing of computers and telephones. Delays became routine and, although no one complained, tension was omnipresent.

It was ironic that this was one of my busiest fall seasons ever. The repertoire I had to prepare – seventeen concertos for piano and orchestra, two full recital programs and a Lieder recital program – was enough to tire out even a seasoned veteran. I barely noticed when my upper left arm felt sore after a weekend in Kingston, Ontario, where I had just performed all five Beethoven concertos. It had been a thrilling experience, but by the end my arm felt like lead and throbbed with pain. I ignored it and moved on to Chopin in Calgary and Bartok in Stavanger, Norway, where the December sun made only a vague appearance at midday and Harry and I shopped for Christmas tree ornaments. Harry had joined me there and the orchestra had put us up in a rustic little cottage near the hall. We enjoyed ourselves thoroughly; the concerts went well, and we were finally together again.

After Norway there were no more concerts until January, so we booked ourselves into a “Wellness Hotel” in the Bavarian Alps for three days. I had generously given Harry my lingering cold, which I had caught in Iowa months previously, so he spent two of the three days in bed reading books and surrounded by mounds of Kleenex. The mercury dropped to –20 and a winter storm raged outside. Gone were all thoughts of picturesque hikes in the snow-covered mountains. We were more or less prisoners in the hotel, but I had discovered they had a beautiful swimming pool and was using it frequently. I remember quite clearly walking past a mirror clad in only my bathing suit and noticing that my left arm appeared to be quite swollen. I remarked on this to Harry, who took a look at it, but neither of us was particularly perturbed. I had read somewhere that tennis players often develop big muscles in their right arms from overuse and decided that in my case the over-development just happened to be in the left arm.

Christmas, our first as a married couple, was pleasant and greatly enhanced by our newly acquired Norwegian ornaments. There was plenty of snow in Bavaria, and the Christmas markets were enchanting. I slipped back into “Frau Oesterle” mode and found myself caught up in the intense social whirlwind of a German Christmas. For a shy person like myself, this was sometimes intimidating, but people were very tolerant and I was eager to fit in amongst Harry’s vast circle of friends. I was becoming more and more enamored of Bavaria and its Baroque churches, awe-inspiring abbeys, fairy-tale cities and divine countryside.

On New Year’s Eve, Harry and I walked up to the top of a nearby hill, the snow crisp under foot and glistening under a brilliant moonlit sky. At the stroke of midnight, the fireworks began and church bells from all the surrounding villages rang out in celebration of the New Year. It was a precious moment of happiness and of hope.

The next morning, I was back at the piano working furiously on my upcoming recital program. In an attempt to kick-start my somewhat neglected European career, which would enable me to cut back on North American concerts so that I could spend more time with Harry, I had offered to presenters a blockbuster recital program which included the ferociously difficult, complete Transcendental Studies of Franz Liszt for the spring of 2002. Much as I passionately love the music, I admit this was a bit of a gimmicky “tour de force” for, up to that point, few men and perhaps no women, other than myself, had ever attempted this feat in a live concert. Various presenters on both sides of the Atlantic were seduced by the idea and invited me to their cities, with the end result that, although I had my usual recital tour in North America, there was also a magnificent tour of Europe lined up, beginning in March of 2002 and including London, Paris and Rome, as well as appearances in Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany and Great Britain.

On January 13th, 2002, I tried out this ferociously demanding Liszt program in front of a large group of friends in the concert hall at Irsee. The following day I traveled back to Connecticut alone to prepare for a month of concerts in North America. Harry was to join me the following week.

At this point my upper arm looked gigantic and was extremely stiff and sore. I decided to visit a chiropractor who had once helped me. He took one look at the swelling and made an appointment for me to visit a local orthopedic surgeon. I also decided to try acupuncture. For a few sessions long needles were stuck into my hands causing extreme pain and frightening the daylights out me. The acupuncturist assured me that the growth was diminishing inside. It was not; quite the contrary. The surgeon decided that I should have an MRI taken of my shoulder and upper arm. Out in Connecticut, they had the latest machine, not the old ersatz coffin version, so mercifully it wasn’t too claustrophobic since I could see out the sides; rather like having a very large hockey puck hanging over oneself.

Although the pain was a bit worrying, what with the upcoming, grueling schedule, I wasn’t at all concerned that whatever was wrong couldn’t be treated and rectified quickly. The absurd notion of cancer barely crossed my mind. My brain was too busy with the Liszt etudes and refused to be distracted by anything else.

The first inkling that things might not be quite so simple came with the results of the MRI and the doctor asking me in which hospital I would prefer to have my biopsy: the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City or the hospital at Yale University in New Haven. In my innocence I answered this serious question lightheartedly and without much thought, plumping for New York over New Haven because I thought it would be more amusing for Harry. The results had indicated that there was a large growth wrapped around my upper arm muscles and the doctor felt there was a certain amount of urgency involved. An appointment was made to meet Dr. Carol Morris the following Tuesday in New York. As one is wont to do, I immediately built up a picture of Dr. Morris: someone short, bespectacled, with black hair streaked with grey severely tied back in a bun, wrinkled forehead, bad teeth, in late middle age and, of course, brilliant. Except for the brilliant part, my imagination had gone badly awry. For it was not a gnome but a goddess who walked into the examining room where I sat joking and waiting with Harry that Tuesday. Young, tall, slender, fine-featured with the most beautiful, delicately formed hands, she entered the room surrounded by her acolytes, an aura of stillness and authority about her, like a high priestess. She was extremely serious, carefully explaining my options and strongly suggesting an immediate biopsy, warning me that even if I didn’t have cancer, the tumour (it was now officially called a tumour) should nevertheless be removed, and I would risk some damage to my arm muscles.

“How much damage?” I asked, “Would it affect my piano playing?” The answers were ambivalent.

I chose to believe that all would be well and was upset only because the biopsy was forcing me to cancel several concerts. Very early on it had been drummed into me that one never cancels concerts, that it was somehow unethical, so many of my concerts had been played with a raging fever or worse. And to lose a concert due to illness sometimes meant never being invited back to certain cities. The battle for my career had been hard fought and there hadn’t been a cancellation in over twenty years. It hadn’t been easy to reach the plateau of relative stability I now enjoyed, and I hated to risk jeopardizing it even by the loss of only a few engagements.

Dr. Morris was very serious and offered no optimistic platitudes. But I remained basically cheerful and almost without doubts. I blotted out the negatives. The concept that a cancerous tumour could exist in my arm with the power to damage my pianistic skills and consequently destroy my life seemed preposterous.

On the morning of January 31st, 2002, just over two weeks after I had played my Liszt recital in Germany, Harry drove me to the hospital. We had left our house in Connecticut at 5.30 a.m. and without any traffic to impede our progress we sped along the deserted Parkway in the steely grey light of pre-dawn, arriving in New York just as a winter storm began to blow in earnest. Neither of us had slept much the night before, mainly because we had to get up very early and, typically, had no faith in our alarm clocks. I still wasn’t particularly frightened by the pending surgical procedure: rather, I was fascinated by the whole experience.

At first, after I had checked in, signed various forms, submitted to the various tests and answered various questions, I sat quite happily with Harry in the waiting room observing the other patients. A very large family of Romanian descent sat huddled together at one end of the room. There were at least four generations present and they had brought along masses of delicious looking food, all carefully wrapped in aluminum foil and stuffed in large containers. They created a rather festive atmosphere in their corner, chatting and eating with enthusiasm, although I felt a little sorry for the grandmother in her hospital gown who was, of course, not allowed to partake of the feast. She was soon called to the operating room and the family left, probably to have breakfast nearby as their appetites seemed boundless.

In another corner a couple quietly intoned mantras. He was desperately ill, emaciated and with skin the color of parchment; I could hardly bear to look at him but, filled with guilt at being so healthy, I forced myself every so often to meet his eyes and proffer an encouraging smile.

Before long, though, everyone was gone, and Harry and I were alone. We were eventually told that Dr. Morris was performing emergency surgery and that my procedure would be delayed.

Harry and I sat silently holding hands in the deserted room. Clad in only a thin hospital gown and the regulation, hideous, puce-colored cotton dressing gown, and not having eaten since the previous evening, I became chilled to the bone and developed a throbbing headache. Harry hadn’t eaten either but refused to leave my side. The magazines provided were eventually all read, and I was left alone with my thoughts while Harry read the books he had foresightfully brought along to help pass the time. Luckily, a nurse stopped by during the afternoon with blankets for me, as I was, by then, blue with cold.

Gone was the devil-may-care-attitude of the morning. We no longer giggled and told each other jokes or made bad puns to amuse ourselves and other patients. The uncertainty of when I would be called and my physical discomforts began to affect my nerves, although I tried to maintain a brave countenance.

Since this was supposedly an out-patient procedure, and as the minutes continued to tick by, it looked more and more as though we would have to drive back to Connecticut in a raging winter storm right in the middle of the New York rush hour with me in, presumably, less than stellar form. Some birthday for poor Harry!

As I stared at the walls, my thoughts inevitably strayed into dark regions. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center was not new to me. I had been there years earlier to visit my dying friend Dana. She had suffered from various forms of cancer since the age of thirteen, but had managed to bear two beautiful girls and survive until her 40th year when she was ultimately defeated by the disease in this very hospital. We had grown up together in three different countries, gone to school together, shared apartments, had been best friends. Why should she have died and why should I have been spared? What, in fact, was this thing, this alien creature growing rapidly and repulsively in my arm? How did it get there? Why was it there?

I decided these thoughts were counter-productive and tried to concentrate on anything else. When my mother lay dying I would “give” her happy memories to think about. I tried out this tactic on myself and thought of our recent trip to Paris, of our walks in the mountains, of pieces by Chopin, the composer to whom I feel closest, whose music speaks directly to my heart, affecting my emotions with an almost preternatural power.

Finally, around 5:00p.m. I was ushered into the freezing cold, rather shabby operating room. It was such a relief to actually have the endless waiting over that my good mood instantly returned and I chatted happily with the kind nurses and with the anesthesiologist, who had me laughing just before he put me under.

“Ms. Fialkowska!” A voice woke me out of the troubled sleep into which I had slipped. Most of the other patients had either gone home or had been transferred to other wards. Harry was standing by my bed smiling at me with anxious eyes and Dr. Morris was speaking to me. She looked exhausted and was still wearing the blue “shower cap” that surgeons wear, and which looks ridiculous on most but not on her. I wasn’t taking in all she was saying but the message was clear and blunt. I had cancer; the tumour had to be removed.

She spoke of radiation therapy, of chemotherapy, and I tried to comprehend and to be brave. Above all, I kept telling myself not to make a fuss – not to make it difficult for her – for Harry. She said that we would have to discuss how to proceed but that she would first confer with her colleagues about how best to save my arm. I had only one question: would I be able to play the piano after the operation? She couldn’t give me a definite answer and left soon afterwards.

It was close to 7:00 p.m. and I was to be discharged soon. I felt in complete turmoil and very ill. The tubes in my nose and in my wrist and the large cuffs wrapped around my lower legs to enhance circulation started to prey on the more neurotic segments of my brain. I felt as though I was being buried alive. The combination of lack of food and the anesthesia made me feel dizzy and nauseated. My heart started to race. Suddenly there was a loud, fast and scary beeping coming from the monitor by my bed. A cardiologist was hurriedly summoned, and something was adjusted in the intravenous medication.

There was now no question of my returning home that night, and I lingered for hours in the recovery room, drifting in and out of an uneasy sleep. Harry was finally told that I was out of immediate danger and that he should leave and come back for me in the morning. Upset and distracted by the events of the day, he drove home alone in the storm. He had only been to New York a few times in his life, and had never negotiated the trip in and out of the city. My concern for him was so great that I temporarily forgot my own predicament – an effective counterirritant, I thought to myself, and smiled wanly for a few seconds before slipping back into self-absorption.

Would I ever play the piano again?

Chapter 2

Scenes from Childhood (“Kinderszenen”) by Robert Schumann

My first public performance was not what one could term an unmitigated success. History relates neither the obstetrician’s nor the nurse’s reaction to my initial appearance on the world stage in 1951 but, according to family legend, the first words which fell from my mother’s lips following my birth were: “Oh God! Take it away! That’s not a baby – it’s a dried prune!”

Presumably such a remark, inflicted at such a tender age, could damage a person’s psychological makeup for the rest of their life. But this kind of wickedly humorous honesty was a family hallmark and therefore part of my genetic code. At home remarks that would send others scurrying to psychoanalysts were nonchalantly absorbed on a daily basis; to survive one needed to develop either a very thick skin or the capacity for lengthy periods of selective deafness.

That said, there really is a strong streak of eccentricity in my mother’s family that, coupled with a tendency to obsession, makes for an interesting agglomeration of personalities. To mention but two, I had a cousin who, at age seventy, streaked down one of the main streets of Victoria, British Columbia, stark naked, hand in hand with one of the most notorious town prostitutes, because he felt it was an amusing thing to do. And another cousin, a dear, loveable person who, for the Queen Mother’s 100th birthday, sought out and bought the very outfit Her Majesty wore on the day of her celebration, put it on, had his photograph taken proudly wearing it, and then sent copies of the photo to all of the members of his family as well as to Clarence House. But then, my own mother, having received a hand-knitted tea cozy as a wedding present from an elderly friend, decided it was far more suitable as headgear than as a pot cover, and for years wore it during the winter months without a trace of embarrassment. The scary part is that the family found nothing remotely odd in this behaviour.

In addition, the women of my mother’s family have tended to be strong-willed and bossy. And when, by some quirk of fate, there is a member of the family with a slightly more normal (boring?) outlook on life, chances are this poor person, feeling somehow inadequate and at a disadvantage, will seek out a glorious eccentric in marriage just to keep up the family’s reputation and pass the interesting genes on to the next generation. As for myself, the obsessiveness and strong will are definitely there; and eschewing a life of leisure for never-ending hours of struggle in front of a black box with white keys, could be interpreted as mildly eccentric.

We are definitely proud of our “oddness” – no question about it. But when the human cocktail of eccentricity and obsession is mixed with despotic tendencies, the result is sometimes a rather entertaining, perhaps rather overwhelming personality; my mother instantly springs to my mind.

The genealogy of my maternal grandmother is a typical Canadian mixture of Scottish and English adventurers who rose in the ranks of the Hudson’s Bay Company and made their fortunes. One of them, Robert Miles, my great-great-great-grandfather, actually became chief factor of the company and married a remarkable lady from the Cree nation. It has always been a source of great pride to know that I have some First Nations blood running through my veins.

The marriage of Robert and his wife, Betsy, was happy and successful, and their grandson, my maternal great-grandfather, rose to prominence as a great financier, becoming president of the Bank of Montreal and founding the Royal Trust Company of Canada. For his efforts, he was knighted and thereafter was known as Sir Edward Clouston. He was obviously a bit of a rogue, but he enjoyed life and was a kind and philanthropic man, particularly towards his less fortunate relatives, who regarded him always with great affection.

Sir Edward had three daughters; two died very young, and the third, Marjory, was my grandmother. An extraordinary beauty, she also appears to have been extremely strong-willed, especially in her choice of husband. Having been brought up in the lap of luxury and as part of the cream of Canadian Society (such as it was at the end of the 19th century), she was expected to make a high-profile marriage, preferably to a titled Englishman or, at the very least, to someone from a family of equal wealth and power. She chose, instead, a persistent suitor from Victoria who was a “mere” Doctor of Medicine. Although her parents overcame their initial prejudice, some of her other relatives and friends were aghast. The fact that my grandfather was one of the most renowned and decorated research scientists in his field didn’t sway them one bit. In just three generations the family had gone from carrying canoes in the wild and trading fur pelts, to considering an alliance with a professional man as a social faux-pas and a definite “step down.” My grandfather, a parasitologist, had already distinguished himself as a young man with his work in Gambia and the Belgium Congo, isolating the tsetse fly as the carrier of the dreaded “sleeping sickness.” Shortly after the First World War, he was sent to Poland, where a terrible epidemic of typhus was raging. For his magnificent work there, he was given Poland’s highest civilian decoration. Decades later, in 1976, when I was engaged to perform three concerts with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, I spent a day as an honoured guest at the renowned Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. The fact that I was a concert pianist was considered all very worthy, but the delightful attentions and kindnesses that I received from the Dean and the professors were mostly due to the fact that I was the legendary Dr. John Todd’s granddaughter.

My mother, Bridget or “Biddy,” was the youngest of three sisters. Incredibly strong-willed, like my grandmother, she seems to have been totally unsuited to the life she was expected to lead. Many of her early years were taken up in the pursuit of fun, since there were continuous house parties with masses of young people in their home, riding, playing tennis and hockey, acting in amateur theatricals, travelling luxuriously, and leading a life of utter ease. But my mother, early on, apparently developed a strong streak of rebellion, hating her governess–ruled education and desperately wishing she could go to a “regular” school and university to earn a degree and follow a profession. She refused to be a “debutante” and at the age of nineteen, while the family was spending a year in Paris, she suddenly decided she wanted to be a pianist. She enrolled herself into the École Normale de Musique which, at that time, boasted such luminaries as Alfred Cortot and Nadia Boulanger amongst its faculty, and she worked frenetically and fanatically for four years, until 1939 when the family, for obvious reasons, could no longer allow her to remain in Paris. Reluctantly my mother returned home, and her musical career was put on hold indefinitely … or at least until I appeared on the scene. Her only non-musical interest during those Paris years was ice hockey; she played Centre Forward in the European Woman’s Hockey League representing Great Britain, but then defected to the French team.

When her fiancé was killed in the early months of the war, my mother enlisted and earned a degree as a mechanic. She was sent overseas with the armed forces and, once in England, was assigned as a driver/mechanic to the Polish forces in exile stationed up in Scotland, which is where she met my father.

During the early stages of World War II, the Poles were hugely popular in Britain, especially after the heroic performance of the Polish pilots during the Battle of Britain. However, once Hitler had attacked the Soviet Union and Stalin became Britain’s ally, the Poles became somewhat of an embarrassment to the English and American governments who desperately wanted to keep Stalin appeased and the Russians fighting hard on the Eastern front. With Poland occupied by Russian troops who had no intention of leaving, what followed was a tragic betrayal on the part of the allies. It wasn’t that anti-Polish sentiment became government policy, but it certainly wasn’t discouraged in any way, and it flourished amongst left-wing groups in England and Scotland.

And so it happened that one day my mother, sitting in her truck with the window open, waiting to drive a Polish officer to a staff meeting, was spat upon and insulted by a young Scot. My mother returned to the officer’s mess that evening and recounted her story. The Polish officers, who doted on her, made a huge fuss, exclaiming that they would never forget how she had suffered for Poland etc. etc. – all the officers but one, who had just arrived and who was unknown to my mother. His only comment was that perhaps the next time she went out she should take an umbrella! Thus, my parents met, and two years later they were married in London, where they both had been transferred. My mother had become so proficient in the Polish language that she was assigned to the Polish headquarters in the Rubens Hotel, where she served as a translator for the Polish Underground Army.

As I’ve mentioned, my mother was obsessive, quite unreasonable and, on occasion, a bit of a tyrant. But she had a wonderful sense of humour and a wicked sense of fun. A lifelong rebel, she enjoyed flaunting orders, driving through red lights, backing up on major highways when she missed an exit, jumping to the head of queues with panache, and filling out serious forms with witty and thoroughly disrespectful comments. Even in her late seventies, when she was under strict instructions to stay indoors because of a bout of pneumonia, she sneaked out and went skating on the lake in front of our house because, as she put it with her own infallible logic: “The ice was so perfect.” And just to annoy all of us, she recovered from her pneumonia the next morning! She was exasperating, but I loved her.

Of my father’s family I know far less, my father not being interested in such things. All I know is that my grandfather was a Pole who came from the Austrian section of Poland (Poland before World War I was divided into three occupied sections: the Russian sector, the Austrian sector, and the German sector) and that he was fortunate enough to come from this more tolerant section, where he had a successful career in the military, becoming the Commandant of the Austro–Hungarian officers’ school in Wiener Neustadt and eventually rising to the rank of General. He married his best friend’s daughter, Ludmilla von Regwald, whose family owned great tracts of land in Bukowina as well as in Poland. An alleged bon vivant, full of charm, he died suddenly in 1919, leaving my grandmother destitute with three small boys, the war having devastated the family finances.

My father Jerzy, or George, was the youngest son and only eight years old when his father died. They were living in Lwów (formerly Lemberg), where times were terribly hard following not only the horrors of the first World War, but also the failed attempt to re-occupy Poland by the Bolsheviks in 1920–1921, when my uncle Konrad, still only a young boy, acted as a courier for the resisting Polish forces. At one time the family survived only with the help of the American Red Cross and their soup kitchens. But the Fialkowski boys were all over-achievers, and by 1939 my uncles Konrad and Gabriel were already successful doctors of medicine and heads of hospital departments. My father was an electrical engineer with a bright future, working for the German firm of Siemens in Warsaw. Called up to active duty after Poland was attacked by the Nazis, he took part as a young reserve officer in the defence of Warsaw, where the sadly under-equipped Polish army heroically staged the last cavalry attack of modern history against the German tanks. He then was ordered to evacuate and re-join the Polish army in exile. Through many hair-raising adventures, including dodging bullets, avoiding bombs and a daring escape from a prison camp in Romania, he made it to Greece, where he apparently had a marvelous few days sightseeing before embarking on a transport ship to France. My father had a passion for travel, and nothing made him happier than visiting exotic places, preferably in warm climates (even in the middle of a war!). After France he finally ended up in London via Scotland. During the war, he worked in the Polish underground as a communications expert.

Miraculously, my strong-willed grandmother and two uncles survived both the German and Soviet invasions, my uncle Konrad having been interned by the Gestapo and later persecuted mercilessly by the post-war communist regime. My uncle Gabriel, although a less intense, more happy-go-lucky fellow, also suffered mightily from deprivations and persecution; among other things, his home in Lodz was first commandeered by retreating German troops and then by Russian troops, who he found had chopped up all of his furniture to use for firewood! The rest of the family – cousins, uncles and aunts – were either killed or deported to camps, Nazi or Soviet. Some survived and one, a resistance fighter, escaped to South America after the war, but was hunted down by the communists and assassinated. My father spent over seven years without knowing if his mother was dead or alive, and only ventured back to Poland to see his family in 1958, after Stalin had died. Had he returned earlier he would most likely have been shot.

In Canada, my father worked for General Electric and then, when my maternal grandfather died, he retired from engineering and took over my mother’s third of the family estate, located on the western tip of Montreal Island, transforming it into a beautiful apple farm. He loved the property and was very happy living there, so long as he could travel each year to Europe or somewhere unusual. My father’s idea of heaven was to walk for hours in Paris, where he had studied as a young engineer, revisiting the “quartiers” of his youth. Since this coincided very much with my mother’s feelings about her early experiences in Paris, I always felt that their best times together were during our frequent trips to France as a family. My father was passionate about politics and read constantly, but although extraordinarily charming, in Canada he was very much a recluse, and could go weeks on end seeing no one but the family. Once he was in Europe, this changed dramatically and he became gregarious; I believe he just felt more at ease with the European style of life, of thought, of rapid conversation and discussion, as opposed to the natural reticence of English Canada.

But what my father cared for above all was his children. He was devoted to us and was always there whenever we came to him with any problem, wise and ready to support and reassure with reason and calm. My brother Peter had a particularly close relationship to him, and they often travelled all over Europe together while I stayed home with my mother and practised the piano.

Thanks to my parents, I grew up at ease with both cultures and inherited a profound love of Europe, a strong interest in politics and a passion for gardens and apple trees.

My ambitious mother suffered mildly from the notion that, because as a girl she had never received a university degree or even a regular high-school diploma, her intellectual upbringing was somehow disadvantaged. Au contraire, her massive general knowledge of history, politics, art, music, literature, and poetry (of which she could recite hours and hours in three or four different languages) would have put many a university professor to shame. What she possessed was a remarkable mind that positively thirsted for knowledge and remained sharp and ever curious right until the end.

She was also an inveterate organiser and a perfectionist and, perhaps due to her upbringing and early social status, was extremely self-confident in social situations. So, it was partially out of her own frustrations at not having had the chance to continue her musical studies or, indeed, pursue any other kind of profession, that she focused on her children’s development with passion and commitment.

My brother Peter, three years older than myself, is one of the family’s most delightful and gifted eccentrics. But he was definitely not the appropriate recipient of this barrage of ambition and discipline from my mother. Instead, he escaped into a fantasy world, which he generously shared with me. He created an entire universe with kingdoms and time machines, armies and palaces, knights, cowboys and gangsters (all inspired by books he read or countries we had visited) and magical, imaginary places like “Ishkabible” and “Iccadiccadaccidak.” Peter would be the narrator and would play the part of all of the characters but mine. I was entranced and enthralled by his imagination and his absurd sense of humour. I can still see us walking up and down the driveway for hours and hours after I had finished my work, in any kind of weather (even snowstorms and days of 30 below Fahrenheit), totally oblivious to the elements, completely caught up in our fantasy world.

I sometimes wonder what would have happened to me if I hadn’t had a brother who had utterly no interest in kicking balls and playing with other little boys but preferred my company and the world we created between us. He was always popular at school because he was so witty and such a good mimic, but his thoughts were never concentrated on anything scholastic or group oriented. For a little girl who was already sitting for five hours a day at the keyboard as well as attending regular school, those few hours with my brother each week were a true lifeline.

It was a crushing blow when he was sent away to boarding school in his early teens. My mother had had to give up forcing him to practise the piano because at one point Peter just dug in his heels and refused to co-operate, although he has loads of talent and had really become quite proficient. My father would patiently help him with his schoolwork and at university, seemingly without ever cracking open a book, he breezed through the courses and obtained his degree. Because of his good looks and talent, he was much in demand and always landed the lead parts in university theatricals, but the rigours of the acting profession were not for him, and in the end, he preferred a quiet life working for years as a television news-anchor and meteorologist in Peterborough, Ontario. His obsessions still include ocean liners, operas, railroads, sailing and trips to France. He was my closest ally as a child, as I was his, and he remains the best brother imaginable. My gorgeous Italian sister-in-law, Luisa, keeps him reasonably grounded, although many would affectionately consider him to be mad as a hatter. They have five children between them, and it is a relief to report that Peter’s two, Caroline and John, whom I love dearly, carry on the family tradition of eccentricity. Luisa’s three, Valerie, Andrea and John-Paul, are genuinely delightful and are an excellent counterbalance.

My mother found more fertile ground for her ambitions in her daughter. Peter was already playing the piano quite well when, at the age of four, I was clamouring to learn how to play myself; the sounds my brother was producing by pressing down the keys intrigued me. And so it was that my career began. My first piece was a Polish Christmas Carol, “Jezus Malusieńki,” that I played for my father as a Christmas present. Shortly thereafter, I was enrolled in the Sacred Heart Convent in Montreal as a day-pupil. My parents were unusual in Quebec society at that time, as my mother was a non-practising Anglican and my father a practising-on-his-own-terms Catholic. They decided the children should be brought up Catholic, as my father did actually attend church every Sunday and my mother never saw the inside of a church except for a funeral, a wedding or, more likely, as a tourist in Europe. I’m pretty sure they wanted us to be exposed to some sort of religion so we could develop our own theological philosophies later on. My father attended the village church regularly, but when we grew up and no longer went with him, he discontinued the practice because he found the local priests to be at best uninteresting and, at worst, as he would put it rather bluntly, “idiots.” He had strong beliefs, including some significant spiritual feelings for the pilgrimage town of Lourdes, where he had gone to pray at difficult periods in his life, including his time in France during the early days of the war. But he often found Church doctrine meddlesome and intrusive, mixing into areas he felt were none of its business. In many ways my politically ultra-conservative father was, in fact, an extremely forward thinker.

Actually, my mother was a far more religious person than my father; I think she had a very strong sense of faith, even though she was a child of agnostics with no real religious background at all. She had a wonderful sense of irreverence towards organised religions and never failed to chuckle over some of the passages from the reams of Catechism I was forced to learn by heart every day at the convent.

I loved going to school and I enjoyed all the rituals of the Catholic upbringing: the lily parades, the first communion, the incense, retreats, candles, ribbons, and medals. Confession every week did strike me as a little ludicrous and, already a performer, I worried that the priest would get bored with the tiny scope of my sins and found myself spending a great deal of energy and imagination dreaming up more exotic ones to keep him entertained; I believe he was quite amused. Unlike most of the other little girls, I never felt any desire to become a nun, probably because already, at the age of five or six, the concepts of freedom of thought and individualism had taken hold in my young mind. Also, I was already ambitious, and the thought of wearing black robes every day seemed rather dreary; the life of the Cloister and of obedience didn’t strike me as much fun or worthy of aspiration.

The education at the Convent in the 1950s was based heavily on learning pages and pages of grammar, Catechism and history by heart. Luckily for the nuns, early Canadian history is full of the exploits of Jesuit and other Catholic missionaries (not to mention nuns), so they had a field day, and it was all very exciting for a young mind – to ghoulishly revel in the horrific stories of Fathers’ Brébeuf, Jogues and Co.’s martyrdoms at the hands of my aboriginal ancestors. I also believe that this early memorising provided excellent training for when I later started to develop my repertoire at the piano. To this day I memorise new pieces extremely quickly, and I attribute this small but useful talent to the style of education I received at the Sacred Heart Convent.

Many of the nuns were from poor Irish backgrounds or French-Canadian country families, and their characters ranged from boorish to mostly very pleasant and kind. But occasionally one struck gold, as I did in my third and fourth year, when I was taught by a remarkable woman, the younger daughter of a distinguished Montreal family – the Duchastels – who were friends of my grandparents. Quite elderly at that time, she was highly civilised, well educated, had a wicked sense of humour and was a totally delightful person. I loved her dearly and believe the feeling was reciprocated. I flourished under her guidance, loving school and eagerly absorbing any bit of knowledge she would impart. However, she never seemed to award me any of the ribbons or medals so beloved in Convent life and that she would lavish on the other little girls. In frustration, I once asked her why I was always overlooked, citing my good marks and general good behaviour; Mother Duchastel just nodded wisely and, smiling, pointed out that I didn’t need any extra encouragement and that I was already far too pleased with myself!

In 1960, when I was nine, my world changed drastically and irrevocably. That summer we travelled to France, ostensibly for a family holiday. However, Biddy had ulterior motives, a vision of my possible musical career having taken hold in her mind. At the time I never questioned my mother’s actions or motives. One didn’t in those days. Besides, I was a self-satisfied little creature with plenty of ambition and a major desire to impress my parents. It was still all a big lark to me.

I had learned a short program to play for her pre-war piano teacher, Mademoiselle Anne-Marie Mangeot in Paris. The program (unimpressive by the standards of today’s mini-monsters, who play Rachmaninov’s 3rd piano concerto at the drop of a hat, shortly after leaving the cradle) consisted of a Bach two-part invention, a movement from a Mozart Sonata, Debussy’s “Golliwog’s Cake Walk,” and a Cramer Etude. After hearing me play, Mlle. Mangeot suggested to Biddy that perhaps now was the time for me to start up serious music studies at a conservatory or music school. This gave Biddy the green light to intensify and lengthen my practice sessions with her and the search was on to find me a teacher.