1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

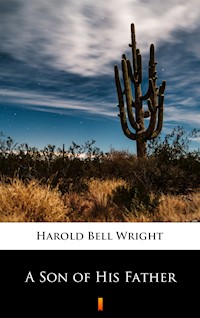

In "A Son of His Father," Harold Bell Wright crafts a poignant narrative that delves into themes of identity, familial duty, and personal redemption. Set against the backdrop of the early 20th century American West, the novel marries vivid descriptive prose with a rich, character-driven plot. Wright's literary style embodies the optimism and challenges of frontier life, reflecting the cultural transitions of the time. The book serves as both a coming-of-age story and a meditation on the profound influence of parental relationships, exploring how a son's journey can be both a quest for self-discovery and an attempt to honor paternal legacy. Wright, a prominent figure in early American literature, harnessed his own experiences as a son and his Christian faith to inform his writing. Growing up in a culturally rich, yet financially strained environment, he drew inspiration from the complexities of family life and struggles during his youth. His deep understanding of the human predicament and search for meaning shines through in this work, suggesting that personal narratives can profoundly shape one's values and decisions. This novel is highly recommended for readers who appreciate a rich narrative woven with moral dilemmas and heartfelt character development. Wright's exploration of familial bonds and the journey to self-understanding resonates deeply, making this book a timeless read for those interested in the intersection of personal and familial narratives.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

A Son of his Father

Table of Contents

CHAPTER ITHE GIRL IN THE TOURIST CAR

With the right background and proper perspective, the most commonplace things of our everyday lives assume colossal proportions.

A westbound, overland train was somewhere between Kansas City and El Paso. Through two long, hot, dusty days a young woman in the tourist car had been, to her fretful fellow passengers, an object of curious interest.

Those who had been with her on the train from New York to Chicago knew that she had come from the great eastern city; but any one could see that New York was not her home. Slow-witted from their grimy discomforts, and indolent from the dragging hours of their confinement in the stifling atmosphere of the second-class coach, they wondered about her with many speculative comments. Who was she? Where was she from? Where was she going—and why?

Whenever the feeble attractions of a perspiring card game failed, the players invariably turned their attention, with pointless jests, to that lonely figure in the queer-looking dress. One couple—a swagger man and a tawdry woman, who were improving their traveling hours with a cheap flirtation made the bundle, which served the strange passenger as a traveling bag, a mark for their ill-concealed merriment. When book or magazine palled, the listless reader would stare at her until a flash of sea-gray eyes would send the intruding gaze guiltily back to the neglected page. At meal time or whenever the train stopped—as even a westbound overland must occasionally do—the common interest was transferred, but never for long. The usual stock remarks about the various sections of the country seen from the windows and the inevitable boasting comparisons with the various back-homes represented were exhausted. Political issues were settled and unsettled. The condition of the country was analyzed, accounted for, and condemned. But always, when every other point of conversational contact failed, that lonely young woman served.

And the young woman was as interested in the curious passengers—but with a difference. If she knew and cared that they were whispering about her, she was careful to show no concern. If she felt their laughter, she gave no sign, save perhaps a flush of color and an odd little smile as if she were trying to enjoy the joke.

As the long hours of the westward journey passed, and the towns and cities became smaller and farther apart, and the might of the land made itself more and more felt, the girl stole a wistful glance, now and then, at her fellow travelers. She was so alone. At times, as she gazed upon the broad rolling miles that now lay between the swiftly moving train and the distant skyline, there would come into her expressive face a look of bewilderment and awe, as though she were overwhelmed by the immensity of the scene. Again, there would be in her eyes a shadow of fear as though she were not altogether sure of what awaited her at her journey’s end.

At the first station west of El Paso a deep-bosomed country mother with a babe in her arms came into the car and was conducted by the porter to a seat across the aisle and a little behind the young woman. From her window the girl had seen the stalwart, sun-browned, rancher husband and it was not difficult for her to picture the home life thus represented. As she watched the mother and child, her face was as if she shared their happiness.

In strange contrast to the hurried passing of the miles the slow hours dragged wearily by. The young woman now looked out upon a wide expanse of dun, gray desert lying between ranges of barren, purple hills. From rim to rim the earth lay dry and hot under a sun-filled sky which, in the blue vastness of its mighty arch, held no cloud. Save for the disturbing rush of the passing train she could see, in all the dun, gray miles, no moving thing. As far as the eye could reach, the only visible mark of human life was that thin, black thread of steel. The gaunt and treeless mountains were set as if to mark the awful boundaries of a forbidden land, but from east to west that curving line was drawn with a bold, mathematical determination in daring defiance to the grim and menacing desolation.

Is it too much to say that these threads of steel constitute the warp of our national life as it is laid on the continental loom? And these fast flying trains—what are they but shuttles, weaving the design of our nationality? The factory villages and the mighty cities of our Far East—the farms and towns of our Middle West—the far flung cattle ranches and the wide ranges of our West—are these more than figures in the pattern of our whole? Consider then the threads that are carried by these swift train shuttles to and fro across the loom: planters, lumbermen, manufacturers, farmers, teachers, artists, writers, printers, priests, devotees of pleasure, slaves of the mill, servants of truth, enemies of righteousness—colored with every shade and tone of every race and nation in all this wide, round world.

But there were no luxurious, overland train shuttles for those hardy souls who first dared to go from east to west across the continent. Slow ox teams and lumbering wagons on dusty trails, under burning skies carried the human threads of that perilous weaving. Ah, but the quality of that old-fashioned thread! The strength, the courage, the conviction, the purpose of those lives that were firm spun on the wheels of adversity from the heroic fiber of the generation which first conceived the design of our nation! The weaving was slow, but the work endures. For us the warp was laid—to our hands came the shuttles—to us the unfinished pattern. But what of the quality of the thread which, in our generation, is being woven into this design, America?

Occasionally, now, the girl in the tourist car caught fleeting glimpses of human life in the seemingly empty and silent land—a red section house on the right of way, a dingy white blur of cattle shipping pens, a distant ranch house, a windmill with watering troughs, a pond where cattle came to drink, the lone shack of some hopeful homesteader. And then, with a long-drawn scream from the whistle and the grinding of brakes against protesting wheels, the headlong rush was checked and the train stopped.

From her window, the girl saw a cluster of unpainted shacks and adobe cabins, one street with three forlorn stores—hardware and implements, general merchandise, drugs and soft drinks—a dilapidated post office, a disreputable garage, a weather beaten hotel, and a tiny depot. From the station platform one might have thrown a stone in any direction beyond the city limits. Some two or three miles away a cloud of smelter smoke towered above a small group of low, black hills. A few natives—cowboys with fringed chaps and jingling spurs, Indians in the costume of their tribe, and town loungers in shirt sleeves and big hats—had gathered to witness the event.

Many of the passengers, excited as children over this break in the monotony of their journey, hurried from the coaches to snatch a breath of clean air while walking up and down the platform and “viewing the sights.” But these travelers, who were so alert to anything new or strange, failed to notice that which caught and held the attention of the young woman at the tourist car window. A little apart from the general gathering, a small company of men and women were grouped about a man who wore on his hat a wide band of black. The man’s hat was old but the band of black was new. On a baggage truck near by there was a coffin.

The conductor, watch in hand, hurried from the station. He paused beside the man in mourning and with him and his friends stood watching as the truck with the coffin was moved toward the forward end of the train. Then the conductor raised his hand and turned: “All aboard,” and the careless, sight-seeing passengers, with laughter and jest, rushed for the coaches. The girl at the window saw the hurried handshakes and the quick good-bys of the man’s neighbors and friends while one of the women placed a tiny bundle of humanity in his awkward arms. The train started hurriedly as if impatient to be off and away to business of more importance. The porter conducted the man, with the new band of black on his hat and the baby in his arms, to a seat in the tourist car.

The man was roughly dressed but clean, with hands that told of heavy toil. His face was the face of a self-respecting laborer. His eyes were heavy with sleepless nights and with grief which he had no skill to hide. The porter’s manner was marked by a gentle deference not usually accorded his second-class passengers. The other occupants of the car settled themselves in various attitudes of weary discontent—indifferent to anything but their own discomforts. The sea-gray eyes of the lonely young woman in the queer-looking dress were misty with tears.

The people who were privileged to sit on the rear platform of the observation car watched the lonely little town fade into the immensity of the lonely land. They saw that column of smoke above the group of low, black hills but gave it no thought just as they gave no thought to the generation that had so bravely laid the lines of steel over which their luxurious train shuttle flew so smoothly. Not one of them dreamed that their children, from the observation platforms of the future, would look upon a city there of which the nation would be proud. They did not know of the riches hidden in those bare, forbidding hills. They had no vision of the fields and orchards that would tame the wildness of the desert. They could not see the homes and schools that would come to be. With thought only for themselves and their little passing day they were as dead to the future of their country as they were indifferent to its history, and apparently cared as little for either the past or the future as they did for that coffin for which their train had stopped.

A train man passing through the car paused a moment beside the man with the baby and, as if he wanted somehow to help, adjusted the window shade. The conductor came, and his voice was kindly and sympathetic as he answered the man’s low-spoken, anxious questions. And in the eyes of the watching girl a smile shone through the mist of tears.

An hour or more passed. The man, holding the baby in his arms, sat motionless, gazing stolidly at the back of the seat before him. Many of the passengers dozed. The couple behind the girl talked in low, confidential tones.

Suddenly, above the noise of the train, came a wailing cry. The man with the baby started and glanced hurriedly around, with a look half frightened half appealing.

The cry came again—louder and more insistent. Several passengers stirred uneasily and looked about with frowns of annoyance. The man, with hoarse, murmuring voice and awkward movements, endeavored to quiet the awakened infant. The cries only increased in volume.

By now the passengers were turning in their seats with looks of indignant protest. A complaining voice or two was heard. The man, confused by the attention he was receiving and helpless to quiet his child, was pitiful in his embarrassment.

The swagger man and the tawdry woman exchanged remarks. A passenger across the aisle, hearing, concurred, and the man, thus encouraged, spoke in a tone which reached half the car: “If people can’t take care of their darned kids, they’ve no business bringin’ ’em on the train.” His companion, in the same vein, supplemented his effort with: “It’s outrageous—where’s the squalling brat’s mother anyway?”

The passengers who heard murmured their approval of this outspoken protest. The man with the crying baby glanced back over his shoulder in mute apology. The young woman, who had been the object of their careless comments and thoughtless jests, sprang to her feet and turning faced the two who had won the applause of the disturbed company.

“For shame!” she cried in a clear voice which was heard easily by those who had endorsed the sentiments of the couple. “Have you no pity in you at all? Or is it that your hearts are as cold as your eyes are blind?”

The swagger man grinned up at her with impudent boldness. His seat mate tossed her head. The startled passengers stared and waited with breathless interest.

With fiery recklessness the young woman continued: “There’s no need of me askin’ if you have any babies of your own—such as you would not—though ’tis to be supposed that you both have fathers and mothers of a sort. As for that poor little one’s mother that you ask for, ma’am, you should know where she is—she is in the baggage car.”

A sudden understanding fell upon the listening passengers. Eyes were lowered or turned away. Faces that were half laughing became grave and troubled. The pair before the girl hung their heads in shame.

A moment more and the anger went from her face. With a suggestion of a smile that was like sunlight breaking through a rift in stormy clouds, she said gently: “I ask pardon, ma’am and sir. ’Tis myself that is thoughtless. Of course it is only because you do not understand that you are so cruel. Forgive me,” she favored the others with a knowing glance, “after all, everybody is just as human as they know how to be.”

At this two-edged apology every face in the little audience caught the light of her smile, and the effect on the atmosphere of the car was magical. The guilty couple, to whom the apology was tendered, alone missed the point, but they smiled with the rest.

The young woman did not pause to note the effect of her words. Even as the light dawned upon the slower witted ones she was standing beside the distracted man who was so engrossed in trying to quiet the baby that he had scarcely noticed the rebuke administered to the complaining passengers. “Please sir, let me try,” she said gently. “’Tis easy to see that you’re near worn out with worry—poor man.”

The father lifted up his face to her with the look of a stricken animal that can not understand why it should be made to suffer so. “I’m mighty sorry, Miss. I know we’re disturbin’ everybody, but it seems like I just can’t do nothin’. I—” He again bowed his head over the wailing infant.

Then the man felt a light hand on his shoulder, and the girl was bending over him—her generous, loving soul shining in her sea-gray eyes. “I know—I know,” she murmured. “But please, sir, let me have the little darlin’. Don’t be afraid. ’Tis true I’ve none of my own—yet—but I know all about them just the same as if I had for ’tis me that’s been mother to my own brother Larry since I was five and he was like your little one here. Is it a boy now? Of course it would be. I was sure it could be no girl from the power of his cry. ’Tis good lungs he has, which is as it should be, praise be to God.”

She had the baby in her arms now and was crooning an Irish lullaby. The man’s sad eyes were fixed upon her glowing face with wondering gratitude. The passengers, as they watched, smiled their increasing admiration. The baby continued to cry.

And then, still singing her low murmuring lullaby, and followed by the eyes of the passengers, the girl with the babe in her arms moved down the aisle of the car to the seat where the country woman was holding her own sleeping infant.

The woman smiled a welcome; and if there was a touch of matronly pride in the superior conduct of her own child, who could blame her?

“Poor little thing,” said the girl, referring to the wailing infant in her arms, “would you just have a look at it, ma’am?” She lifted a tiny, claw-like hand. “See how ’tis nothing but skin and bones. And is yours a boy or girl?”

“Mine are all boys,” returned the mother—pride mingling with her sympathy.

“All boys! What a grand thing it must be now to mother a brood of men. This one is a boy, too. But the poor little thing’s mother is dead and gone, you see, and they’re trying to raise him on a bottle, which by the look of him is doin’ no good at all. We raised my brother on a bottle—mother bein’ so weakly and not full-breasted like you—beggin’ your pardon, ma’am, but Larry he took to cow’s milk like a calf—he was that strong-stomached and healthy. Your little one there is a beauty now, isn’t he? My—my—would you look at the fat little hands and the roly-poly cheeks and legs of him, and how he’s sleeping with his little self as full as he can hold! ’Tis a wonderful boy he is, ma’am, and all because you’ve so much to feed him.”

The woman’s face beamed. “My last two was twins.”

“Twins? Glory be! But sure ’tis plain to see how easy it would be for you to feed two.” She bowed her head over the baby in her arms. “There, there, you poor little hungry darlin’—with the mother that bore you cold in her coffin.” Suddenly she looked straight into the other woman’s eyes and in a low voice that was filled with pity and horror said slowly: “’Tis plain starvin’ to death he is, ma’am, no less.” She paused an impressive moment. “And—” she added with a pleading smile which fairly glorified her countenance, “and you a mother with more than plenty for two.”

Gently the woman laid her own sleeping child on the seat. Blushing with embarrassment because of the observing passengers she received the stranger’s infant in her arms. The wailing cry died away in a queer little, gurgling murmur.

The girl looked triumphantly around at the beaming faces of her fellow travelers—proud of this vindication of her faith in the goodness of human kind. “He’ll be all right now,” she said reassuringly. “’Twas him that knew all the time what he wanted and had to have.”

“God bless her dear heart,” exclaimed a mother whose sons back home were in their college years. The man who had encouraged the rude remarks of the couple across the aisle wiped his eyes and blew his nose quite openly. The porter was one broad ebony smile of courteous attention. The swagger man, leaving his companion as if their affair had suddenly lost its flavor, paused on his way to the smoking compartment to offer the girl a stammering apology. Throughout the car there was a glow of friendliness, with low-spoken words of admiration for the young woman in the queer dress whose traveling bag was a “funny bundle.”

When the girl carried the now sleeping babe back to the father, she said: “If you please, sir, I’ll just sit down and hold him a little. ’Tis easy to see that you’re near worn out, and I do so love the feel of a baby in my arms.”

The man made room for her on the seat facing him, and tried in his awkward way to thank her.

“My name is Crafts—Milton Crafts.”

“Thank you, sir, and mine is O’Shea—Miss Nora O’Shea.”

Milton Crafts bobbed his head in polite acknowledgment of the introduction; and then for a few moments there was silence between them, while they both looked out at the whirling landscape.

Presently, as if she would turn him from brooding over his bereavement, the girl said: “’Tis a great country you have, sir,—with your cities and farms and homes and factories back there in the east, and all this room out here for to build more of the same.”

“It’s big enough,” he returned stolidly. “And where might your home be, miss?”

“Where else but in Ireland?” she returned, smiling.

“’Twas in Kittywake, County Clare, that I was born, and there I lived, never leaving it for any place, until I started on my way to America where my home is to be, now, with my brother Larry—him that I raised as I was tellin’ you.”

“I live back there in Oreville,” said the man simply. “I work in the mine.”

“My brother Larry works on a ranch,” she returned. “Our father was a teacher, and you can believe, sir, we was that poor we was often put to it to fill our stomachs with anything at all. But in everything save money, sir, we were rich. Father and mother—God rest their souls—wedded for love, do you see, and against the wishes of mother’s family—they belonging in a small way to the gentry—and so, afterwards, they would have nothing to do with us.”

“Uh-huh, I don’t know so much about your gentry, as you call ’em over there, but if your mother’s folks was anything like my wife’s father, God help Ireland, I say.”

“Amen to that, sir, and God help America if you have many such here, which I know you have not. ’Tis a wonderful land, sir, is America. My father used to tell us all about it. Many’s the time we would say ‘if only we could get to America, how happy we would be.’”

The man looked at her curiously—almost as if he suspected her of attempting a joke at his expense. “My wife took more after her mother—I’m going with her to Tucson now. Tucson was their home, you see, and her mother is buried there. I—”

“Tucson!—Is it Tucson you say? Why, man, that’s where I am going myself—to be with my brother Larry—only Larry don’t be in the town but on a big ranch, as you call it, somewhere near—Mr. Morgan’s ranch it is. It’s for him my brother works. Well, well, and it’s to Tucson that you are going now with—with the little one!”

“Yes, ma’am, Jake Zobetser—he’s my wife’s father—is going to take the baby. My friends they all said it was best to let it go that way ’cause the little feller would have so much better chance with his granddad than he ever could with me. Jake, he’s got all kinds of money. But I don’t know—I wish I was sure I’m doin’ right about it. It’s kind of hard, sometimes, for a body to know just what is best, now ain’t it, miss?”

“Indeed, and indeed it is that. Many’s the time I’ve been put to it to know which way I should turn—with the mother sick and Larry left for me to raise.”

“Your father and mother ain’t living now, I take it?”

“No, sir, my father died of a fever when Larry was a lad, and mother went just before I left the old home to come to this country. ’Twas her that held me there so long. She was never well after Larry was born, and that’s how it comes I had to be mother as well as sister to the boy. Well then, after father’s sickness and death, mother got to be clean helpless. Larry and I did our best—he working in the quarry and me doing what I could with my needle besides nursing mother and looking after the home—but our best wasn’t much, sir. And so, you see, whenever things were going harder than usual, we would just keep on dreaming of America and wishing we was there where there’s nothing like there is in Ireland to keep any one down, and everybody can have enough to eat and a real home—if they’re the kind that wants it.”

Again the man looked at her with that curious, half suspicious expression. “I’ve heard that kind of talk before,” he said at last, grimly.

But Nora O’Shea, in her enthusiasm, overlooked the meaning of his remark. “’Tis no doubt you have, sir—and a grand thing it is to be said of any country. Well—and so, you see, when my brother Larry had a chance to come to America we said he must go. I stayed at home to take care of the mother, but it was understood between us three that when the time came I was to go to Larry and make his home for him.”

“Your brother got him a good job, did he?”

“Indeed, and he did that. Larry is that kind of a boy—as I raised him to be. He was a year in New York and one in Philadelphia, and all the time sending home the money to keep the mother and me. And then he met Mr. Morgan—it was in Philadelphia, that was—and Mr. Morgan took him back with him to Arizona and gave him a fine place on his big ranch. But maybe you know Mr. Morgan?”

“No, I ain’t never seen him that I know of. I’ve heard of the family though. It is one of the big pioneer ranches—Las Rosas, I think they call it. Jake Zobetser’s got a place somewhere in that section of the country.”

“That’s it, sir—Las Rosas—that’s it. Ah, but he’s such a fine American gentleman, is Mr. Morgan! And that good to Larry and our mother and me—you could hardly believe. Larry’s letters were full of him. It was from Mr. Morgan, you see, sir, that my brother got all the money we had to have when mother was nearing the end. It came just in time, too, thank God! And there was plenty to help her to go in comfort and to make a decent funeral such as she had a right to—with enough left to bring me to America. So here I am, where I’ve so long wished and prayed to be—and all because of Mr. Morgan being such a grand man, and that good.”

“You’re aimin’ to live at the ranch with your brother, are you?”

“As to that, I don’t know. But Larry will have it all arranged. There was no time, you see, for me to get a letter from him; because the minute I was free to come I was in no mind to wait. But, however it is, we’ll have a grand little home of our own somewhere—just like we’ve always dreamed about. Will you be stopping in Tucson, sir? I would be proud for you to meet my brother.”

“No, I’ll have to be on my way back to my job, by this time to-morrow. With them doctor bills waitin’ and a lot of other things to pay yet, I got to be hittin’ the ball. I wouldn’t live in the same town with Jake Zobetser, nohow. I wish I knew it was goin’ to be all right for the boy.”

“There now, there now, don’t you be a-worrying yourself sick about crossing bridges that are not even built yet. ’Tis natural there should be a thistle here and there amongst the clover, but bad as some folks may be and cold-hearted and all, there’s good in them yet, just as there’s good in everybody if only it can be got at.”

“You expectin’ your brother to meet you in Tucson, are you?”

“Indeed and I am. Larry will be at the station sure. I sent him a letter that I was coming.”

“That’s fine—you’ll be mighty glad to see each other again, I reckon.”

“Indeed, sir, I’m that happy I can hardly hold myself.” She bent her head low over the baby in her arms so that the man might not see the tears of gladness which she could not control.

The never-tiring shuttle flung onward through the darkness of the night, carrying the human threads for its weaving. And so, at last under the brilliant Arizona stars, they labored up the heavy grade to the summit of Dragoon Pass, thundered down the other side, roared across the San Pedro Valley, climbed again to the higher levels between the Whetstones and the Rincons and, sliding easily down the long slopes into the mountain-rimmed valley of the Santa Cruz, stopped in Tucson.

Except for the Irish girl and the man with the baby, the tourist car passengers were long since in their berths. The porter, carrying the man’s suitcase and Nora’s bundle, led them down the dim, curtained aisle and out into the night. With a sincere, if awkward, expression of gratitude and a quick good-by which the girl scarcely heard, Crafts, with the baby in his arms, hurried away toward a man and a woman who were coming slowly to meet him.

Eagerly, anxiously, Nora O’Shea scanned the faces of the few people who at that late hour were at the station. Taking her bundle, she went a little way toward the waiting room, then paused to look questioningly about.

A group of passengers from the Pullman cars made their way to taxicabs and hotel buses. The conductor and train men exchanged greetings with the relieving crew and went away to their homes. Men in overalls inspected the wheels, iced the water tanks, and groomed the overland for the continuation of her run to the coast. Presently the new conductor signaled, the porters climbed aboard, and the train started. Train men swung on to the steps, vestibule doors were banged shut, the rear lights twinkled a moment and vanished around the curve beyond the Sixth Avenue crossing tower. The men with the express and baggage trucks pushed them into the buildings and shut and locked the heavy doors. The scene, save for an old Indian who sat on the ground with his back to the station wall, and the young woman in the queer dress with a funny-looking bundle, was deserted.

CHAPTER IIFATHERS AND SONS

Everywhere in Arizona, the old and the new stand hand in hand—Past and Present are intimate. Side by side with all that is modern, one may see the mysterious ancient out of which the modern has come.

The builders of our concrete highways, through the greasewood and cacti of the desert, drive their giant tractors over the petrified trunks of forest monarchs that flourished here eons before the plans were drawn for the oldest pyramid in Egypt. Searchers for the materials demanded by manufacturers of our latest inventions find, embalmed by nature’s processes and hidden in their mountain tombs, monstrous creatures that lived remote ages before the beginning of life as we know it. Where get-rich-quick development artists build their pasteboard and plaster bungalows one may find traces of a people who builded here so many ages ago that no scientist is daring enough to name the century of their activities. No one knows when the old pueblo, which in the time of our pioneers became Tucson, was first established. We do know, however, that when the only settlement on Manhattan Island was a small group of bark covered huts—when the site of Philadelphia was an unmapped wilderness and the prairies of Chicago were an unexplored region—Tucson was a walled city.

The Tucson of to-day, in the heart of this old, old land, is a city of fathers and sons. The fathers, with their ox teams, stage coaches, and Indian wars, laid here the foundation upon which they hoped their sons would build a civilization worthy of the race. And the sons are building.

With feverish activity they are putting down pavements, putting up electric lights, putting down gas and water pipes, putting up real estate signs, putting down more city wells, and extending the city limits to include new additions of the surrounding desert. With a fine contempt for the past they have destroyed the ancient wall, demolished many of the picturesque adobe structures of history, renamed the century-old streets, converted the beautiful old Saint Augustine church into an unsightly garage, and erected dance halls where, within the shadow of a heroic past, their sons and daughters may have all the modern advantages of a thorough education in jazz. On the very spot where men died to save their wives and children from the knives of painted savages, and women fought and endured beside their men, the grandchildren of those courageous souls hold petting parties and are bold only in their indecencies.

It is not strange, when you think of it, that the fathers should sometimes speak of the old days with a note of regret. It is not to be wondered at if they sometimes view the trend of their sons’ improvements with dubious eyes.

In this land of the old and the new this girl from far across the sea found herself unexpectedly alone. She could scarcely grasp the truth that her brother Larry had failed to meet her. Every hour of the long voyage—every hour of the long days on the train, she had looked forward to that moment of her arrival in Tucson and to her meeting with the boy to whom she was, as she said, “both sister and mother.” Save for Larry there was no one in the world to whom she could go. Her devoted heart, aching with the grief of her mother’s death and burdened with the sadness of those last days in her old home, wanted the comfort of his love. When the careless indifference of her fellow travelers had magnified her loneliness, she had found strength in the joy of her anticipated companionship with him. When the strangeness of the new, wild land had oppressed her with a sense of fear, she had found courage in the thought that she was going to Larry, and that with him she could not be afraid.

She would not leave the station. Certainly, she could have found a hotel; but what if Larry should come for her and find her gone? No, no, she had written Larry to meet her at the train. She must wait right there until he came. Every moment she watched for him. Every moment she expected him. She saw the stars in the east grow dim as the sky back of the dark hills was lit with the coming dawn. She watched the shadowy bulk of the mountains taking form. The gray of the sky changed to gold and crimson and blue. The sun leaped above the hill tops. Purple shadows filled the canyons. The world was flooded with light and color.

The morning brought a stir of life about the station. Nora asked and learned that there would be another train from the East during the forenoon. Perhaps Larry had thought that would be her train. She had her breakfast at a little restaurant across the street, and ate with her eyes on the station entrance, lest Larry should come and not find her there. A crowd of people assembled. There was the usual train-time activity. The train arrived and went on its way. The crowd dispersed. There would be still another train from the East in the afternoon. She must wait.

Many of the people, as she watched them come and go—Indians, Mexicans, Chinamen, Japanese—appeared strange, indeed, to this Irish girl who had never before been away from the place where she was born. The mountains that on every side lift blue peaks above canyon and foothill and desert—the feeling of vast space—the very quality of the atmosphere—impressed her with a sense of wonder and awe. The curious desert plants in the station grounds filled her with amazement. And, surely nothing could be more unlike her Irish home than this quaint, old-new city in a land which to her was all so strange. For Nora O’Shea, at least, Tucson was a place of mystery—a wonder-place of queer people who must, she imagined, do dark deeds and know strange delights. Beyond a doubt, danger lurked in these crooked streets, wild adventure waited. If only Larry would come!

While the Irish girl was waiting for her brother Larry through the lonely hours of that day, Max Drayton, one of the Tucson fathers, was entertaining a visitor at the Old Pueblo Club. Solid and substantial both in physique and character, Max, in his western way, is a philosopher—which is to say, he believes in men as a whole the while he watches individuals with studious care. His judgments are invariably based upon a broad human charity—his observations are pointed with a rare humor. Drayton’s guest was an author, making his first visit to Arizona. The two local papers agreed that he was famous, and implied, at least, that if the distinguished visitor were not already the dean of American letters he was in line for that honor.

The stranger looked about at the very modern and really excellent appointments of the Old Pueblo Club with a faintly concealed air of disappointment. “Really, you know, I am surprised.”

There was an understanding twinkle in Drayton’s shrewd eyes.

The writer continued: “This is all—well—it is not exactly what one expects to find in Arizona, you know.”

“It’s a pretty good little club.”

“And your hotels, too.”

“Hotels? What’s the matter with our hotels?”

“Matter with them? Nothing, nothing at all, I assure you. It is only that I was not looking for exactly this sort of thing—you understand.”

“Oh, I see. This is your first trip to Arizona, is it?”

“Yes.”

“What do you think of the movies?”

The author, not being familiar with Drayton’s mental processes, waited a blank moment before answering: “The movies? Well, I can’t say that I consider the motion picture to have reached a very high state of development from the standpoint of pure art, as yet, but they certainly are very instructive. From an educational standpoint their value is tremendous.”

“I guess you’re right.”

Drayton’s guest continued: “I confess I never miss one of those wild western things.”

The man, who had lived so many wild western years, smiled, as one who finds his opinion justified.

Gazing across the table at his gray-haired host with an eagerness that was both flattering and sincere the author said: “I can’t tell you, Mr. Drayton, how happy I am to have this opportunity of talking with you. For a long time I have wanted to write a novel of the West—one of those stirring, red-blooded stories of real life, you know.”

“Is that so? And you’ve come to Tucson for your material, have you?”

“Frankly, I have. I find—” he waved his hand in a comprehensive gesture.

Max Drayton chuckled.

The writer smiled ruefully. “I confess: when I stepped off the train I expected to see cowboys standing around, wearing guns and big hats and high-heeled boots with spurs and those fringed legging things made of leather, you know. I’ve been here three days and haven’t seen but two people on horseback—a man and woman—and they wore English riding breeches and rode English saddles.”

Drayton laughed so at this that the university president, who was sitting at a neighboring table, smiled in sympathy.

“Seriously, Mr. Drayton,” said the author—evidently anxious for the red blood he had come so far to find—“where would one go to see the real West?”

“Right, here, of course,” came the proud and ready answer. “We’re just as far west as we ever were.”

“But surely, Tucson wasn’t always like this.”

“Like this! Well, I should say not. But, for that matter, neither was New York always like it is to-day. It’s still New York, though. If you don’t believe it, you just ask some old timer there and see how quick he’ll set you right.”

Max Drayton’s manner was, at times, a little gruff—verging even on the aggressive. The seeker for red blood murmured a “beg pardon” which Max did not even hear. “The fact of the matter is,” he was saying, “Arizona is just as much the real West as it was in the days you’re thinking about. You haven’t caught up with us, that’s all—you’re too slow. I am not so sure,” he added thoughtfully, “that Arizona has caught up with herself—yet.”

It was the Eastern man’s turn to smile.

“You people in the East,” Drayton continued, “are still thinking of us here in the West as we used to be in the old days when every man wore a gun just as natural as he wore his pants. But you don’t think of Ohio and Kentucky and Pennsylvania that way. And yet, when the pioneers first went into those states guns were just as common to them as they ever were to us out here. Talk about being wild and woolly! Why, I don’t reckon there ever was a place that was wilder than Massachusetts was about the time the Pilgrim Fathers were packing their shooting irons to church and prayer meeting. The only real difference between the East and the West is that we, out here, are living a little closer to the pioneers. We haven’t got so far from where we started as you folks have, that’s all. But we’re travelin’, my friend—we’re sure travelin’. The thing that’s interesting a lot of us old timers who helped to make this country is this: While we’re sheddin’ our wild and woolly ways, and getting shut of our guns and all that, are we throwing away a lot of things with ’em that we ought to hang on to?”

“Just what do you mean, Mr. Drayton?”

“I mean, that in those days when we were pulling all that motion picture stuff that you call the real West, and that you’re planning to make your story out of, we had a lot of ideas that would be mighty good for us to have right now.”

“Yes?”

“Yes. You take even our gamblers—the old time professionals, I mean—they had mighty well set standards of honor and decency and fair play that they lived up to and sometimes died for. The old-time, wide-open, gambling days are gone—and we’re all glad of it—but I’m telling you, sir, it wouldn’t do us a bit of harm if a lot of our young business men of these days had some of the old-style gambling standards of honor and decency and fair play, and had ’em strong enough to die for ’em—if it was necessary.”

“Oh, I see.”

“Sure! And you take the spirit of brotherliness and neighborliness now: Why in the old days we were just like one big family. By Ned! we had to be. Some black sheep, of course, like every family has; but if anybody was in trouble of any kind everybody was right there ready to help. Now, we’re all so split up into clubs and circles and cliques and clans that you dassn’t say “good morning” to your next door neighbor, unless you’ve got the right password. I tell you, sir, a man could starve to death right here in Tucson before these young organizers could untangle enough red tape to find out what was the matter with him.”

The author—he was really an understanding writer—silently nodded assent. Drayton continued: “There’s another thing; men used to be more certain—whether they were good or bad, friends or enemies, you knew where to find ’em; and you could gamble on finding ’em right there all the time. To-day, nobody knows where anybody stands on anything; and, mostly, by the time you find out where a man is, he ain’t there at all. Do you see what I mean?”

“Indeed, I do.” Then the author harked back on his trail for blood: “But, Mr. Drayton, is there not, here and there in Arizona, a good bit of the—the old color left?”

“Sure—that’s what I say; we’re still so close to the pioneer days we haven’t shed quite all of it yet. There’s plenty right here in Tucson.”

“Here?”

Max’ eyes twinkled. “Sure, right here.”

“Could I—would you—”

Max looked around. Through the wide arch of the club dining-room entrance they could see the lounging-room with the library and reading-room beyond. “Do you see that man over there by the window?”

“The portly old gentleman—reading?”

“That’s the one—that’s Colonel Brandonwell. Brand was a scout during the Civil War—up in Colorado and Wyoming. He came to Arizona along in the seventies and was Deputy United States Marshal in Tombstone. Brand has fought Indians and outlaws all over this Southwest.”

The author, gazing at the gray-haired, well rounded, perfectly groomed, benevolent-looking gentleman in the easy chair, murmured a polite something and Max continued: “Take a look at the pair with their heads together over in the corner.”

“You mean the small man and the professor-looking gentleman?”

Max laughed. “They’re the ones—the smaller is Ned Hale—the professor gentleman, as you call him, is Charlie Baylong. They are both the sort you read about and see in the movies—went all through the Indian troubles when Geronimo was staging his red-blood stunts. They were in the cast, too, when the Apache Kid was putting on his famous motion-picture raids. Charlie, he’s vice-president of one of our banks now, and a pillar in the Presbyterian church. And look—that’s Fred Herrington just coming in. He is another of our wild and woolly ones.”

“Surely not that distinguished-looking gentleman,” protested the author. “Why, he looks like one of our prominent Philadelphia lawyers!”

“Is that so? Well, don’t make any mistakes—Fred is a lawyer all right but he’s one of the old timers too. Ask our club secretary, George Crider, that kindly, even spoken, gentleman you met when we came in—he’s another who has lived through more red-blood stories than ever you’ll write. And there’s a lot more about town, too. But most of them have passed on—Bob Leatherwood—Cap Burgess—Bill Cody and—”

“Buffalo Bill?”

“Sure—he was a member of the Old Pueblo Club. They’re going fast, though—these last two or three years.” Drayton’s voice dropped and for the moment he seemed to lose himself in the memories awakened by his guest’s interest in the men of the West.

“But—but, Mr. Drayton—these men that you point out are all retired.”

“Is that so? Huh! Maybe we’re in the process of being retired, but there’s quite a bunch of us sticking around yet—watchin’ for what’s likely to happen to the boys that have just climbed into their saddles. You see, all of us old timers know mighty well what Arizona was—but God Almighty only knows what Arizona is going to be when this generation gets through with it.”

The author was distinctly conscious of a thrill. He was disappointed in not finding the exact shade of crimson he sought, but still—still—there seemed to be something—“I suppose—” he began, and paused. Max was gazing intently at a young man who at that moment entered the club, and the writer noticed on his host’s kindly face an expression of peculiar interest. Turning his head, he also looked at the man who was greeted by nearly every one in the room.

In years, he was somewhere between twenty-five and thirty, but with a decidedly boyish look on his smooth, deeply tanned face. Standing well over six feet, his back was straight, his shoulders broad, and he bore himself with that air of strength and confidence best described by the good and familiar “ready for either a fight or a frolic.” It was not at all difficult to guess that he was a great favorite among his fellows.

The author looked again at his host’s face and saw the fondness and pride which the philosopher was at no pains to hide. But back of the fondness—or, perhaps, because of it—there seemed to be a troubled question.

The old pioneer spoke slowly: “You say you want to see a real, live, honest-to-goodness cowman? Well, there he is.”

“What! Where? You don’t mean the big chap in the good-looking gray clothes—why, he looks more like a college athlete.”

Drayton chuckled. “Well, as a matter of fact, he is—but don’t fool yourself, he’s a cowman too. I’ve seen him ride broncs that had piled the best of them, and as for roping—even the Mexican vaqueros have had to hand it to him more than once.”

The author caught his breath. “Broncs”—“Ropes”—“Vaqueros”—the color—the precious color! For the moment he saw that university-looking young man through a—to put it mildly—pink haze. Then he spoke in an awed whisper: “Who is he?”

Drayton, whose mind seemed, now, somewhat preoccupied and disturbed, answered mechanically: “Jack Morgan—Big Boy Morgan, we all call him.”

“And do you mean it—is he a real cowboy, or are you spoofing me?”

Max returned to his guest and to his duty. “Real? I’ll say he’s real. He’s not exactly a cowboy, though. But as for that, there’s not a puncher in the Southwest that can show him anything. He is the owner of Las Rosas, one of the biggest ranches in Arizona.”

At this, the author was excited indeed. Who could say—there might still be a chance to save his novel of Arizona life from the wreck of things. With admirable self-control he managed to ask: “Is this ranch near Tucson?”

“About sixty miles south and west, on the other side of the Serritas, in the Arivaca country, down near the Mexican line.”

The author breathed a long sigh of relief. This certainly was more like it. “You can’t imagine how interesting this is, Mr. Drayton. Do you mind telling me more?”

“About Big Boy Morgan, do you mean?”

“Yes, if you don’t mind.”

Drayton looked thoughtfully toward Morgan who was the center of a little group of men. “There is not much to tell,” he said slowly, then he added as an afterthought: “yet.”

“He was born here in Arizona, was he?” prompted the author.

“Oh, sure—born right there at Las Rosas, and went to school and the university here in Tucson. He’s never been out of the state, so far as I know, except a few trips to California, and one visit back East last year to Philadelphia.”

As he spoke the concluding words of his summary, Drayton’s voice was unconsciously lowered and his speech slowed down while his eyes turned once more toward the subject of his remarks.

The author murmured suggestively: “Philadelphia?”

Max Drayton looked straight into the eyes of his guest with a directness that was, to the other, a little disconcerting.

“My home is in Philadelphia, you know,” the writer said apologetically.

“Is that so?” But still the man of Arizona held him with that steady gaze. “Do you know the Grays, there?”

The eyebrows of the writer went up. “The Charles Lighton Grays?”

“Yes.”

“I know of them, certainly—one of our finest and most exclusive old families.”

“Morgan’s father and old man Gray were great friends. There is a son, Charlie, about Morgan’s age. Big Boy was visiting them.”