9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

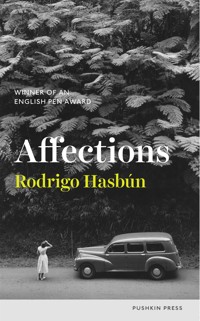

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

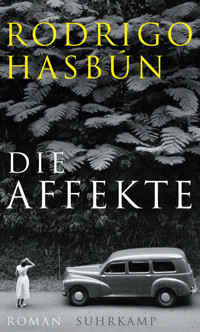

Loosely based on real events, Affections tells the story of the eccentric, fascinating Ertl family, headed by the egocentric and extraordinary Hans, once Leni Riefenstahl's famous cameraman and Rommel's 'personal photographer'. Having fled Germany shortly after the country's defeat in the war, the family now lives in Bolivia. However, shortly after their arrival Hans - an enthusiastic adventurer and mountaineer - decides to embark on an expedition in search of Paitití, a legendary Inca city. The failure of their outlandish quest into the depths of the Amazon rainforest proves fateful, initiating the end of a family whose subsequent voyage of discovery ends up eroding everything which once held it together.Against the backdrop of the both optimistic and violent 1950s and 1960s, Affections traces the Ertls' inevitable breakdown through the various erratic trajectories of each family member - from Hans and his constant engagement in colossal projects, to his daughter Monika, heir to his adventurous spirit, who joins the Bolivian Marxist guerrillas and becomes known as 'Che Guevara's avenger' - and the story of a woman in search of herself, the story of the heartrending relationship between a father and a daughter, the story of a family adrift.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Affections

RODRIGO HASBÚN

Translated from the Spanish by Sophie Hughes

PUSHKIN PRESS LONDON

Although inspired by historical figures, this novel is a work of fiction. As such, it is not, nor does it attempt to be, a faithful portrait of any member of the Ertl family or the other characters who appear in its pages.

CONTENTS

I

PAITITÍ

The day Papa came back from Nanga Parbat (with his soul-crushing footage, so much beauty wasn’t human), he explained to us over dinner that alpinism had become too technical and that the important things were being forgotten, that he wasn’t going to climb anymore. Clearly believing his words held some kind of promise, Mama grinned like an idiot, but she kept quiet so as not to interrupt. “Man’s communion with nature is what really matters,” he went on, his beard longer than ever and as dark as his faintly deranged eyes, “the chance to reach places God himself has forsaken is what matters. No, not forsaken,” he corrected himself at the start of one of his interminable monologues, the ones he always gave when he got back, before the silence grew again, and with it the desire to set off on a new adventure, “but rather those places He can be found, where God finds solace away from our ingratitude, and our depravity.”

Monika and Trixi hung on his every word, entranced. Mama too, naturally. We were his clan, the women who waited for him, up until then in Munich but now in La Paz, where we had been living for a year and a half. Leave, that’s what Papa knew how to do best. Leave, but also come back, like a soldier returns home from the war to gather his strength before going again. There usually followed a few months of peace. This time though, having only just bemoaned the state of alpinism, and with his mouth half-full, he declared that he would soon be leaving in search of Paitití, an ancient Inca city buried deep in the middle of the Amazon rainforest. “No one has laid eyes on it for centuries,” he said, and I couldn’t bear to look at Mama, to see how short-lived her hope had been. “It’s full of hidden treasures buried there by the Incas to protect them from the greedy conquistadors,” he added, although these riches were the least of his concern. The prize he coveted was finding the city’s ruins. It turned out he’d made a decisive stop in São Paulo on his way back from Nanga Parbat and finally had the funds and equipment to set off. “Let’s not forget how long Machu Picchu went undiscovered,” he said. “For hundreds of years, nobody even knew it existed, until bold Hiram Bingham came along.”

Papa knew the names of hundreds of explorers, unlike me. I was one year off finishing secondary school and had other things to worry about, like what I was going to do afterwards. La Paz wasn’t so bad, but it was chaotic and we would never stop being outsiders, people from another world: an old, cold world. We had at least managed to adapt now, after months struggling with every single thing, including blasted Spanish. Mama barely spoke a word of it, but my sisters were becoming increasingly fluent and I could get by without too much trouble. My other option was to go back to Munich, but the fact that Monika was considering this too put me off, because if she did we might end up living together. She had just celebrated her eighteenth birthday, had recently finished school and was more confused and angry than ever. With her recurring panic attacks she had somehow managed to wangle it so that everything revolved around her even more than before, and Trixi and I had to resign ourselves to being minor characters, a bit like Mama in relation to Papa. I’m not going to deny it, it wasn’t a pretty sight watching my sister having one of her hysterical fits. It was shocking, horrifying even. The last time we’d had no choice but to tie her up. Did Papa know about that yet? Had Mama told him in a letter maybe? Or earlier that day, before supper, as soon as they were alone in their room? Despite months of imploring by Mama, Monika just shrugged it off (“It’s nothing,” she would say. “Leave me be.”), and she refused point-blank to see a psychiatrist or physician.

In any case, ten days after Papa’s return, my sister’s inner turmoil would coincide with another: the archaeologists from the Brazilian institute whom Papa was waiting for told him that they had to postpone the start of the expedition. He either didn’t understand their reasoning or took it as a personal affront, and all hell broke loose in the house. Over the following days we listened to him make endless calls, slam doors, make threats, rant and rave. He spent the rest of the time brooding like a caged animal, like a man who’d lost everything. We girls were on school holidays and had no way of dodging this display of martyrdom. In the end, while Monika and I were helping him in the garden one afternoon, he suggested to her that she go with him. My sister didn’t know if she wanted to study, or what or where she would study if she did. It was she who had questioned his decision to settle in Bolivia, complaining incessantly, even on the boat over. “We can’t just up and leave our lives like this,” she would begin, before really letting rip. “This isn’t the way to do things!” “Not many people get the chance to start over,” Papa would reply, and Monika would say, “There’s no such thing as starting over. Leaving is the coward’s way.” Confronted like this, Papa would go quiet and his silence gave her free rein to go on, at least until he lost his patience. And when this happened Mama would tell me and Trixi to take a turn out on deck, and they would go on arguing, sometimes for hours on end. I would come to understand my sister’s misgivings later, the day we arrived in La Paz. I recognized nothing in the city (there were children begging on the streets, native people carting great big bundles on their backs, too many half-built houses to count), and everything seemed unsafe and dirty. It was a couple of months later, with the family now settled in a central neighbourhood and Papa having already set off for Nanga Parbat, that Monika’s panic attacks began. That was nearly a year ago. Now, in the garden, to my astonishment she accepted his offer without a second thought.

Of course, Papa was trying to kill two birds with one stone: to count on Monika’s help for the expedition which, as we then learnt, he’d decided not to delay by a single second, and to put some distance between her and her demons and apprehensions. Having listened to him, incredulous, I announced that he should take me too. “You’re still in school, you idiot,” my sister cut in. “I can miss a couple of months,” I told her, keeping my cool and promptly turning back to Papa. “Something like this could be life-changing for me,” I said, “you of all people know that.” What must it have been like for him coming home after such a long time spent in inhospitable environments and with only men for company? Was there something we didn’t know that had made him want to give up climbing? And what was he really after with this business in Paitití? And me, what was I looking for? The chance to skip a few classes? To stand out among my friends and make them seethe with envy when I told them? Not to be left in Monika’s shadow? As if he’d foreseen all this, including the questions I was asking myself, Papa pulled a strange smile as he nodded his consent. My heart froze in my chest and I looked at my sister, who looked at me, and neither of us knew what to say. I suppose it frightened us to realize that he was serious.

“You need to prepare yourselves,” he said after a while. We spoke in German amongst ourselves. On the rare occasions we were obliged to speak Spanish it felt fake. It was getting dark, we’d soon have to go back in. Having finished weeding the garden, all that was left to do was to tie up the hessian sack and dump it on the street. “Materially speaking, we’re more than ready,” he told us. “We’ve got bite-proof suits, radio equipment, special cases to protect the celluloid, a terrific camera. We’ve got everything we need to reach the end of the world.” He was able to buy all this kit thanks to the backing of a Bolivian ministry and the Brazilian institute, who had agreed to his setting off without their team. “This is where the future is,” we’d heard him repeat over the previous days. “Europe had its chance and lost it. Now it’s the turn of countries like this.” He was no longer welcome in ours, regardless of the debt German cinema owed to him. During the Berlin Olympics, in the famous production by Leni Riefenstahl, Papa had been the first cameraman to film underwater and take daring aerial footage, the first to do many things. He’d also spent several years taking impressive photos of the war. Everyone knew about it, and no one better than us. Not for nothing had we had to move continents and abandon our life there. “Materially speaking, we’re prepared,” he repeated in the garden, swinging the hessian sack over his shoulder, “but not logistically, not yet. Nor physically or mentally, and even less spiritually.” Did Mama know? Had they already discussed it? Would we leave without her consent? “It won’t be easy,” he said. “Nobody said it would be. Not for any of us, but we will find Paitití. Paitití has been waiting for us for centuries. We’ll get there whatever it takes.”

* * *