10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

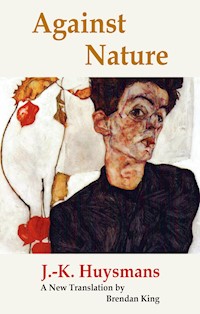

- Herausgeber: Dedalus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Study of obsession and aesthetics in fin-de-siecle France.

Das E-Book Against Nature wird angeboten von Dedalus und wurde mit folgenden Begriffen kategorisiert:

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Decadence from Dedalus

General Editor: Mike Mitchell

Against Nature

J.-K. Huysmans

Against Nature

(Á rebours)

Translated with an introduction and notes by Brendan King

Published in the UK by Dedalus Limited,

24-26, St Judith’s Lane, Sawtry, Cambs, PE28 5XE

Email: [email protected]

www.dedalusbooks.com

ISBN printed book 978 1 903517 65 9

ISBN e-book 978 1 907650 31 4

Dedalus is distributed in the USA and Canada by SCB Distributors,

15608 South New Century Drive, Gardena, CA 90248

email: [email protected] web: www.scbdistributors.com

Dedalus is distributed in Australia by Peribo Pty Ltd.

58, Beaumont Road, Mount Kuring-gai, N.S.W. 2080

email: [email protected]

Publishing History

First published in France in 1884

First published by Dedalus in 2008

First e-book edition 2011

Introduction, notes and translation © copyright Brendan King 2008

The right of Brendan King to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act, 1988

Printed in Finland by WS Bookwell

Typeset by Refine Catch Ltd, Bungay, Suffolk

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A C.I.P. listing for this book is available on request.

THE TRANSLATOR

Brendan King is a freelance writer, reviewer and translator with a special interest in late nineteenth-century French fiction. He recently completed his Ph.D. on the life and work of J.-K. Huysmans.

His other translations for Dedalus include Là-bas, Parisian Sketches, and Marthe, and he also edited the Dedalus edition of The Life of J.-K. Huysmans by Robert Baldick.

He lives in Paris.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Note on the translation

Select bibliography in English

Against Nature (1884)

Preface written twenty years afterwards

Notes

Manuscript variants

INTRODUCTION

The publication of J.-K. Huysmans’ A rebours (Against Nature) caused something of a minor sensation when it first appeared in 1884. As the author himself observed in a special preface to the novel written twenty years afterwards, the book ‘fell like a meteorite into the literary fairground and caused consternation and anger; the press was beside itself.’ It was not that the book was a bestseller in the traditional sense of the term – Huysmans would have to wait another fourteen years and the publication of La Cathédrale (The Cathedral) before his income from writing outstripped his salary as a government functionary – but its provocative flouting of social, moral and aesthetic conventions made it a book that couldn’t be ignored. Of the forty or so reviews that appeared in French newspapers in the wake of its publication there were many that were violently hostile, a few that were fervently enthusiastic, but none that were completely indifferent. Huysmans had spent the previous two years predicting disaster for the book, but for once his habitual pessimism was refuted rather than reinforced by the reality of events. As he explained in an interview written pseudonymously for the paper Les Hommes d’aujourd’hui (Men of Today) in 1885, ‘I thought I was writing for about ten people, opening a kind of secret book that was inaccessible to fools; but to my great surprise I found that thousands of people all around the world were in a state of mind analogous to my own.’

If the novel’s success exceeded the author’s expectations, its cultural impact has also gone far beyond that of the succès de scandale it initially enjoyed. However strange and disjointed it may have seemed to contemporary reviewers, Against Nature gave form and substance to a certain nebulous spirit of the times which up until then had remained undefined. As a result, the novel was enthusiastically taken up by a number of young artists and writers, who saw it as a source of inspiration for a set of ideas and values that coalesced into Decadence, a literary and artistic movement that became emblematic of fin-de-siècle France. As the book’s reputation radiated out from Paris and spread across Europe, its ideas began to influence the literature of other countries too, especially in England and Italy, which each produced their own distinctive Decadence movements.

In the century following its publication, the novel’s uncompromising attitude to art and literature has had a dramatic impact on successive generations of writers and artists – and almost single-handedly redefined the cultural canon of nineteenth century France in the process. Certainly the status of poets such as Mallarmé, Verlaine and Baudelaire, and artists such as Odilon Redon and Gustave Moreau – all of whom were seen as marginal cultural figures at the time the novel was published – would be very different today if Against Nature had never been written.

To most of Huysmans’ contemporaries, the notion that Against Nature would have had a lasting influence on European literature, that it would gain for itself the status of an iconoclastic work in the literary history of the nineteenth century, would have been difficult to comprehend. To their eyes the book had next to no plot, a single, unpleasant – if not downright immoral – leading character who was neurotic, self-obsessed and, what was worse, an effete aristocrat. Taken as a whole, this so-called novel seemed to be composed of a series of bizarre aesthetic speculations and analyses that not only defied the stylistic conventions of the novel form, but ran counter to the prevailing orthodoxies of literary and artistic taste. A review in the Revue Catholique for 15 July 1884 gives an idea of the kind of feelings the book inspired in the average middle-class reader:

M. Huysmans is one of the principal pupils and imitators of M. Zola. Here’s what he’s come up with: his novel has only one character, a young man who is worn out by every conceivable pleasure, has rents of 50,000 francs, and who decides to retire from society because that society is guilty of wearing him out! He decides to furnish his house: then follows a description and enumeration of all the colours one can choose to decorate a house, ten pages of colours. He decorates his house with flowers: then follows a description and enumeration of all the flowers you can get, twenty pages of flowers. These flowers give off various scents: then follows a description and enumeration of all the smells they exhale, thirty pages of smells. He forms a library: then follows a description and enumeration of all the books he has in his library, fifty pages of books. Etc., etc. The young man continues in this fashion … until he decides to cure himself. Then follows a description and enumeration of all the medicaments and enemas he administers from morning to night … He still isn’t cured. And after that? Nothing, that’s it. It’s absurd! It’s stupid, you say. Yes, but if you only knew how tiresome it is!

Against Nature is one of the successes of Naturalist literature, and Naturalist literature is the literature of the Republic.

Unrepresentative as it might be of the whole range of critical responses to Against Nature at the time – some reviewers at least appreciated the novel’s originality and power even if they didn’t like or understand its subject matter – the last line of the review nevertheless provides a clue as to why the book tended to produce divergent and often extreme responses in its readers, whether of admiration or of contempt. Since the establishment of the Third Republic in the wake of the violent and bloody repression of the Commune, a moderate Republican government had been trying to keep the peace between two opposing ideological factions: extreme left-wing Republicans who wanted to see through the programme of the French Revolution on one side, and a mixture of reactionary Catholics and monarchists who wanted to see a restoration of more traditional, hierarchical social structures on the other. This fault-line running through French political life progressively deepened during the 1880s, as Catholics and Republicans fought to impose their respective, but mutually irreconcilable, visions of France. The critic for the Revue Catholique clearly judged Huysmans’ novel against this backdrop of political tension and division. For him, Huysmans was a Naturalist and therefore a Republican, and his novel was representative of what he saw as the worst aspects of an innately anti-clerical, anti-Catholic Republic. Against Nature was what happens when the strict morality of the Church is relaxed and the individual is left to his own devices.

This was not, of course, the only response to the novel. Indeed, as Huysmans himself pointed out at the time, his book seemed to have antagonised everyone:

By the letters I’ve received and the noise that’s reached me, I see there’s a general furore! I’ve trodden on everyone’s corns: the Catholics are exasperated, while others accuse me of being a cleric in disguise… the Romantics are outraged by the attacks on Hugo, Gautier and Leconte de Lisle; the Naturalists by the contempt shown for the modern novel …

(Letter to Zola, May 1884)

Perhaps because Huysmans’ own views about contemporary social and political developments were in a transitional phase – in the late 1870s he had exalted the modern as the proper subject of art, but by the end of the 1880s he saw it as synonymous with crassness and ugliness – there is a certain ambiguity at the heart of the novel. Should Against Nature be read as an apologia for des Esseintes, was it proposing him as a role model, or was it making fun of him? In default of any clear intention on the part of the author, many contemporary readers ended up interpreting the book in the light of their own assumptions or prejudices. Certain writers associated with the Naturalist movement, such as Paul Alexis, Jules Destrée and Gustave Geoffroy, tended to see the book within a specifically Naturalist framework: Alexis, for example, ridiculed Léon Bloy for taking des Esseintes’ mystical enthusiasms at face value rather than as symptoms of a neurotic illness (Le Reveil, 22 June 1884), while Destrée described the novel in straight forward terms as a ‘magisterial study of neurosis and decadence’ in which the ‘mad dreams of an artist are analysed with a scientific acuity and a precision of detail that give them life and the illusion of reality’ (Journal de Charleroi, 21 November 1884).

By contrast, unorthodox Catholics such as Léon Bloy and Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, writers who were fiercely opposed to the scientific and materialistic ideas on which Naturalism was founded, saw the book as a devastating analysis of a society putrefied by materialist values. Bloy, in his typically hyperbolic fashion, noted that Against Nature presented two alternative views of life, one can either ‘stuff one’s face like a beast, or contemplate the face of God’, and that Huysmans, ‘formerly a Naturalist now a spiritualist of the most mystical kind, had distanced himself from the crapulous Zola as much as if all of interplanetary space had suddenly accumulated between them’ (Le Chat noir, 14 June 1884). Barbey d’Aurevilly’s infamous review went even further and after remarking that Huysmans seemed to be detaching himself from the ‘soulless, clueless photographic realists who make up the Naturalist school’, ended with the same prophetic challenge he had made years before to Baudelaire on the publication of Les Fleurs de mal: that after such a book, there logically remained only the barrel of a gun or the foot of the Cross: ‘Baudelaire chose the foot of the Cross; but what will the author of Against Nature choose?’ (Le Pays, 29 July 1884).

Whether the book was taken as a critique of Naturalism or as an unhealthy product of it, it is clear that the novel’s critics and commentators saw the issue of Naturalism not in terms of a narrow debate about a literary movement, but rather as a convenient shorthand for a much larger set of political questions about the role of the individual within society and, ultimately, how that society was ordered. Although Huysmans wasn’t a political writer in an overt sense – his novels were not polemical in the way Zola’s were, and he didn’t publicly ally himself with any particular political party – it was nevertheless the case that during the 1870s he had been an integral member of a literary movement seen to be on the left of the political spectrum, a movement whose books attacked the institutions and the values of the middle class, and which was intrinsically hostile to the Catholic Church. To those sensitive to the way the political wind was blowing, the publication of Against Nature seemed to signal a change in the author’s political commitment, with its criticisms of Naturalism, its contempt for the ‘democratisation’ of art and literature, and its privileging of an artistic and social élite. Huysmans’ original title for the novel was Seul (Alone). The decision to change it to A rebours – which in French means going backwards or against the grain of things – is significant in that it shifts the symbolic focus of the book away from the solipsism of the individual, it contextualises des Esseintes’ existential crisis against the backdrop of the wider contemporary sphere and places him in opposition to the current political and social order of things.

It is no accident that Huysmans himself should have described the book as ‘exploding like a grenade’ (Les Hommes d’aujourd’hui). The ideological battle lines between those on the left and the right had been drawn, and the field of literature was just as much a combat zone as the Chamber of Deputies, the town hall or the pulpit. When Huysmans published Against Nature, it wasn’t just a literary movement he seemed to be rejecting, it was his tacit allegiance to the ideology that went with it. In prioritising the élite over the popular, the singular over the general, and the unique and the rare over objects of mass production, Against Nature stood against what Zola and many of the Naturalists considered to be the forces of progress and allied itself, albeit in an idiosyncratic and abrasive fashion, with those in society who believed in a hierarchical, non-egalitarian social order. The novel therefore represented a movement away from the values of a left-leaning secular Republic and constituted Huysmans’ first public step towards a form of reactionary Catholicism that he would later fully embrace following his conversion in 1892. Writers on the political right such as Barbey d’Aurevilly and Bloy recognised it immediately. And so, too, did Zola.

Writing Against Nature

Huysmans began writing Against Nature in the late summer or early autumn of 1882. His previous novel, A vau-l’eau (With the Flow), which recounted the depressed and depressing life of Jean Folantin, a self-confessed failure whose philosophy of life is summed up in the final words of the book, ‘only the worst happens’, had been published on the 26 January of that year, so in creative terms Huysmans was at something of a loose end. Although he had written to the Belgian author Camille Lemonnier at the end of 1881 to say he was working on a novel called Le Gros Caillou, this was not so much a serious project as a kind of literary makeshift which consisted in trying to develop and expand a short story he’d already published in 1880. As it turned out the novel never got beyond the first chapter and within a few months he confessed he had given it up. In a letter to Guy de Maupassant, written in March, Huysmans admitted he wasn’t working on anything, ‘being completely incapable of stitching two ideas together’. The impetus for a new burst of creative energy was probably a visit in the spring to Jutigny, where he went with his long-standing mistress, Anna Meunier. It was here that he saw the Chateau de Lourps for the first time, a partially ruined chateau which not only served as the model for des Esseintes’ ancestral home in Against Nature, but also formed the backdrop to Huysmans’ subsequent novel En rade (At Harbour) of 1887.

The image of the crumbling ruin of the Chateau de Lourps provided a dramatic contrast to the refined ‘thebaid’ of the stately provincial house in Fontenay-aux-Roses where Huysmans had spent three months convalescing after a bout of neuralgia the previous year. Although there is nothing to suggest that the idea for Against Nature came to him at Fontenay, it is clear that his experiences there – he divided his time between re-reading Baudelaire and planting ‘almost artificial’ flowers in a garden in which ‘nothing has the air of being real’ – provided a rich fund of source material for the novel. The letters he wrote to Théodore Hannon at the time are full of ideas that later reappeared in the novel, and on his return to Paris he published a ‘Parisian sketch’ entitled ‘Pantin’ that played with the notion of real flowers and artificial perfumes and which he later incorporated into Against Nature with only minor changes. In his imagination, the two houses became symbols that functioned on both a political and an existential level: the Chateau de Lourps came to represent an older social order, grander and more refined, but one that was moribund, weakened by aristocratic in-breeding and debauchery, and unable to compete with a commercially-minded bourgeoisie; by contrast, Fontenay became the artificial ‘thebaid’, a retreat in which des Esseintes could escape from the commercialised demands of modern life, a space in which he could re-invent himself and shape an artificial world more suited to his refined aesthetic tastes.

The first reference to the new novel in Huysmans’ correspondence comes in a letter to Stephane Mallarmé of 27 October 1882, in which he asks the poet for help in finding copies of his books, as he wants to refer to some of his poems:

I am in the process of hatching a pretty unusual story, the subject of which is as follows: the last scion of a noble line takes refuge – out of disgust at the Americanisation of life, out of contempt for the aristocracy of money that has invaded us – in complete solitude. He is a cultured man of the most refined delicacy. In his comfortable thebaid, he tries to find a way of replacing the monotonous boredom of nature by means of artifice, he amuses himself with authors from the exquisite and penetrating Roman decadence – I use the word decadence in order to be understood – he even charges off into the Latinity of the Church; into the barbarous, delicious poems of Orientius, Véranius du Gévaudan, Baudonivia, etc., etc. In the French language, he’s mad about Poe, Baudelaire, the second half of La Faustin. You can see where it’s going.

Huysmans’ succinct precis of the book’s subject, which closely mirrors that of the finished novel, shows that the general outline of Against Nature must have come to him at an early stage in the writing, or that he had already been working on the book for a few months before he mentioned it to anyone. Certainly ideas for the book were starting to come to him around this time. In a letter to the Belgian publisher Henry Kistemaeckers on 23 August, for example, Huysmans refers to his recent trip to Jutigny, and, a propos of travelling in general, notes that:

It is just like London. If one buys one’s clothes in Old England, reads Dickens and goes to drink port at The Bodega, one can easily imagine that one is on a journey, visiting that diabolical city …

This is clearly an early version of the conceit that forms chapter XI of the novel, that of des Esseintes’ imaginary trip to London.

In any event, whether Huysmans began the novel in August or September – in late September 1883 he remarked in a letter to Lucien Descaves that it was time he finished the book as he’d been working on it ‘for almost a year’ – it is significant to note that Zola wasn’t the first person he chose to tell about his new literary project. In fact, he didn’t tell Zola about the new direction his work was taking until mid-November:

With the return of the cold weather, I feel better – I have started writing again – plunged into a kind of bizarre fantasy-novel, a piece of neurotic craziness which will, I believe, be something new, but which will necessitate my immediate confinement in the Charenton mental asylum. I have put aside for the moment Le Gros Caillou, which wasn’t going as well as I wanted and which I’ll start again when I’m in a different state of mind. I positively feel the need to put myself out to graze in some black and furious fantasy, mad but real all the same.

This letter shows not just that Huysmans didn’t keep Zola up to date about his work at this period, but that he wasn’t entirely truthful about its progress and direction either. He only tells him in November, for example, that he has given up working on Le Gros Caillou, when we know he had abandoned it in March, and when he does talk about his new work he gives a much vaguer account of the form and substance of the novel than he had given to Mallarmé.

Even at this early stage in its development it is clear that Huysmans was uneasy about how Zola would receive the novel, that he was aware it represented a serious deviation from Zola’s ideas and those of the movement to which he nominally belonged. In his subsequent letters to Zola, Huysmans adopts a persistently dismissive tone towards the novel, as if trying to reassure him about it or play down its importance in his eyes. Huysmans knew that in writing Against Nature he was indulging in a rebellious act, but it is as if he is not quite prepared to take responsibility for it, and frequently gives the impression to his correspondents that the novel is writing itself, almost against his wishes.

Certainly by the early years of the 1880s Huysmans felt that the Naturalist movement as it was popularly conceived had run its course, and he was looking for ways in which to incorporate in his fiction experiences and sensations which Naturalism, with its ostensibly materialist underpinnings, was ill-equipped to deal with. In the course of 1883 we can see Huysmans trying to put some distance between his own philosophical position and that of Zola’s. In a review of Huysmans’ collection of art criticism, L’Art moderne (Modern Art), which appeared in Le Parlement of 31 May 1883, Paul Bourget had remarked in passing that:

This book is called L’Art moderne and its author is J.-K. Huysmans, one of those novelists whom public opinion has classed, without knowing why, under the ambiguous epithet Naturalist. Huysmans has no other trait in common with Zola or Maupassant except having written a short story in the collection Soirées de Médan …

Although this was the only reference to Zola in the review, Huysmans immediately seized on it, and at the beginning of June he wrote a fulsome letter to the critic:

I am particularly grateful to you, my dear friend, for having pointed out that I am in no way a pupil of Zola’s, as everyone else says. Lord, we have no ideas in common, neither in painting nor literature. Even so, there will probably be general astonishment when the bizarre novel I am working on – and which couldn’t be less Naturalistic, at least in the vulgar sense of the word – appears. I hope that you’ll like it, because I often think of you in relation to certain chapters on orchids and combinations of perfumes, on furniture and painting. These will barely be comprehensible to the general public, inasmuch as this carnal, mystical book is veiled under a muslin that lets no hint of violence or the extreme through, but beneath which I hope its sentences will evoke a certain elevation in refined readers like you.

The notion of refinement becomes a recurring motif in Huysmans’ thinking at this time. If there was one thing Zola wasn’t in Huysmans’ eyes it was refined, and he was inclined to regard Zola’s tastes, especially his household furnishings, as bourgeois, even vulgar. The words ‘raffiné’ and ‘raffinement’ crop up frequently in his letters during the early 1880s and, as if to define himself in opposition to Zola, he described himself as ‘an inexplicable amalgam of a refined Parisian and a Dutch painter’ in his pseudo-interview for Les Hommes d’aujourd’hui. Significantly such cultural refinement tends to be predicated on a political and economic system that is at odds with the values of egalitarianism and democracy.

Reading Huysmans’ letter to Bourget and its enumeration of the various chapters on styling and furnishing, one is inevitably reminded of Edmond de Goncourt’s La Maison d’un artiste, an exercise in cultural refinement in which the writer’s house is described room by room, its fine antiques and objets d’art catalogued and classified. La Maison was clearly an influence on the early chapters of Against Nature. Goncourt had sent Huysmans a copy of the book in early 1881 and the younger writer’s letter of thanks shows he was taken with the style of alternating chapters of description, and was flattered that Goncourt had included him in his library of contemporary books – something which probably gave him the idea of including the names of authors he admired in his inventory of des Esseintes’ library.

By the end of November 1883, Huysmans had almost finished the book. As he put it to Zola:

For my part, I am still harnessed to my absurd book; but I am starting the last chapter, the end of the end. It’s true that I still have a lot of tying up to do. I’ve really got myself stuffed into a frightful wasps’ nest with this novel with only one character and no dialogue. It’ll be deadly boring – literally – I’m more and more convinced of it. Anyway, it’s done; I now just want to get rid of it as quickly as possible so I can get on with my novel La Faim, which will give me more scope.

Again, he seems unable to be completely straight with Zola. Not only does he disparage his new book – in a letter to Théodore Hannon a few months later he boasted that his novel was ‘a book that would astonish the world, a book beyond anything that had yet been conceived’ – he also holds out the idea that when it is finished he will return to a more ostensibly Naturalist mode of writing, La Faim (The Hunger) being his novel about the Siege of Paris. In the event, his next novel was not La Faim – which was never finished and which he burned shortly before his death – but En rade, another work in which he tried to incorporate extreme non-Naturalist elements and which he again denigrated in his subsequent letters to Zola.

After the publication of Against Nature, Zola was quick to respond. In a long letter of the 20th of May, he set out his thoughts about the novel, nuancing his positive comments with minor criticisms, and then increasingly giving rein to his feelings of unease:

My dear Huysmans,

I finished Against Nature and I want straight away to give you my sincere impressions.

Beginning very clear, which pleased me infinitely, above all the pages on the Chateau, the bits about the Voulzie, the move to Fontenay very interesting, the pages on colours, the fitting up of the Dining Room with the aquarium, and the hasty voyages made in imagination during meal times. Of the three chapters on literature, the one on Latin Decadence is the one I prefer: there are superb pages in it, written in a grand style, but you have pushed eloquence so far that certain paragraph breaks get lost in the course of the declaration. A bit confusing, too. As for the chapter on contemporary religious literature, I think you have given too much praise to those charlatans; I except Barbey. As for us others, in the end we’re there a little through the indulgence of the author, are we not? Des Esseintes communes very amusingly in Mallarmé. An interesting description of Baudelaire. The tortoise – exquisite, especially with his hanging of jewels, which is a nice refinement. A very bourgeois thought came to me: it’s lucky it died, because it would have crapped on the carpet. An amusing fancy that of the mouth organ, though not easy to imagine as a physical mechanism. Some fine pages of artistic criticism on the painters des Esseintes prefers. Personally, I’ve only a slight interest in Gustave Moreau. I laughed at the stupidity of the woman who wanted to live in a rotunda and what happened to the rounded furniture. I found the story of Auguste Langlois a little laborious, especially as there’s no conclusion. But des Esseintes’ love life entranced me: the acrobat, and above all the ventriloquist, oh, the ventriloquist! it’s a poem … Very colourful pages on plants, even if a little confused, strewn with a few errors, I think. I prefer the section on perfumes, which is absolutely successful, with a magisterial certitude and a lyrical fantasy. As a complete chapter in itself, the voyage to London is a marvel. There is an extraordinary beating rain in it. You have a feeling for rain, there’s a description of it in Les Sœurs Vatard which haunts me. Finally, the falsified hosts and the nourishing enemas are, in a jokey but serious way, chiselled with the care of an artist, and among the most extraordinary things I’ve read.

Do you want me now to say frankly what troubled me about the book? First of all, I say again, the confusion. Perhaps it’s my builder’s temperament which balks at it, but it displeases me that des Esseintes is the same at the end as at the beginning, that there’s no progression whatsoever, that the chapters are always ushered in by a weary transition of the author, that in the end what you’re giving us is a magic lantern show, the slides chosen at random. Is it the neurosis of your hero that turns him to this exceptional life, or is it this exceptional life that causes his neurosis? There is a link is there not, but it’s not very clearly established. I believe that the novel would have been more striking, above all in its transcendental aspect, if you had constructed it more logically, however mad it is… .

In short, you have made me spend three very happy evenings. This book will be classed at least as a curiosity among your books; but be very proud you have done it.

If Huysmans felt annoyed at the condescending tone, he kept quiet about it: his letter of reply to Zola is friendly and even apologetic, and his letters to other close friends make no reference to a falling out between them. In a letter to Jules Destrée, written on 24 November 1884, Huysmans even refutes the current wave of speculation in the press about a break between himself and Zola over the novel’s publication:

As for the so-called rift, trumpeted from the rooftops, between me and Zola, it’s stupid. We often have friendly arguments between ourselves about questions on which we differ completely, but we’ve been friends since before L’Assommoir, and I think of him as a great talent that the press, despite all its agitations, can do nothing to blunt.

And then again, what is Naturalism or Romanticism in the end? What? The truth is that there are some people who have talent and some people who don’t. Barbey d’Aurevilly, who is at the opposite end of the spectrum to me, wrote l’Ensorcelée, and Les Diaboliques, both of which I greatly admire.

In later years, however, Huysmans remembered things differently, and in the preface to the deluxe commemorative edition of Against Nature published by Les Cent Bibliophiles in 1904, he gives a more dramatic account of Zola’s reaction:

What is at any rate certain is that Against Nature broke with its predecessors, with Les Sœurs Vatard, En ménage, A vau-l’eau, that it committed me to a path the final destination of which I didn’t even suspect.

Shrewder than the Catholics, Zola foresaw this clearly. I remember how, after the publication of Against Nature, I went to spend a few days at Médan. One afternoon when the two of us were out walking in the countryside, he suddenly stopped and with a black look in his eyes reproached me over the book, saying that I had struck a terrible blow against Naturalism, that I was leading the school astray and that, moreover, I was burning my boats with such a novel, because no kind of literature was possible in a genre exhausted by a single book; and then in a friendly way – for he was a decent man – he urged me to return to the beaten track, to harness myself up to a study of manners.

I listened to him, thinking that he was both right and wrong at the same time – right in accusing me of undermining Naturalism and completely blocking my own road – and wrong in this sense that the novel as he conceived it seemed to me to be dying, worn down by repetitions that, whether he liked it or not, were of no interest to me.

Whichever of the two versions is true, it is clear that the publication of Against Nature was a turning point, not just in Huysmans’ own development as a writer but in the fortunes of the Naturalist movement as a whole, and this could not but have had an effect on the relationship between the two men. Prior to the publication of Against Nature, Huysmans was seen as Zola’s disciple; after it, he was a literary figure in his own right. It should be kept in mind, too, that Huysmans’ situation in 1904 when he published the Preface was very different to that of 1884. By 1904, the ongoing battle between the secular State and the Catholic Church was reaching its height, the Law of Separation being voted through in 1905. In this increasingly bitter struggle, Huysmans had sided with the Church – though, typically enough, he violently castigated Catholics for their stupidity and cowardice over the matter – publicly criticising the Republic’s actions in his novel, L’Oblat (The Oblate, 1901), in his journalism and in newspaper interviews. In the context of this heightened political situation the ‘Preface written twenty years afterwards’ takes on an extra level of meaning. As both the literature and the religion of the time were so inextricably bound up with particular ideological viewpoints, it cannot be read simply as a neutral reflection of Huysmans’ personal literary and religious development. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that, looking back from the perspective of twenty years and for the benefit of a mainly Catholic audience, Huysmans should have chosen to see Against Nature, a book which a number of Catholics wanted him to suppress or publicly disown, as a foundational text for the remainder of his literary work:

All the novels I’ve written since Against Nature are contained in embryo in that book. Its successive chapters are in effect simply the foundations of the books that followed.

Huysmans’ assessment of Against Nature as his seminal work has been echoed by generations of readers and critics. It remains one of the most bizarre, intriguing and influential novels of the period, and whether read as an existential fable, psychological analysis, style manual, cultural critique or social satire, Against Nature is as audacious and original today as when it was first published.

NOTE ON THE TRANSLATION

The text of A rebours used for this translation is that contained in Volume VII of the Oeuvres complètes (Paris: Crès, 1928–1934), edited by Lucien Descaves. I have also consulted a number of other French editions that provide useful background information on the text and on manuscript variants, most notably Rose Fortassier’s edition for the Imprimerie Nationale (1981) and Daniel Grojnowski’s paperback edition for GF Flammarion (2004).

To avoid confusion, I have chosen to stick with the most common English translation of the novel’s title, Against Nature, even though it is not strictly accurate. In French à rebours can mean ‘backwards’, ‘in reverse’, ‘something done against the ordinary run of things’.

Against Nature is the kind of novel that demands a critical apparatus and extensive notes. It alludes to numerous works and ideas across a wide range of cultural activities and disciplines. However, to footnote every single uncommon usage or obscure cultural reference would unnecessarily burden the text and make it practically unreadable. For this edition, therefore, the text has been left clear of footnotes. Extensive notes are provided at the back of the book for those who choose to consult them. Manuscript variants are listed in a separate section at the end of the book.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY IN ENGLISH

Baldick, Robert. The Life of J.-K. Huysmans, Oxford: Clarendon Press 1955. Revised ed. Dedalus Books 2006.

Bernheimer, Charles. ‘Huysmans: Writing against (Female) Nature.’ Poetics Today, 6(1–2), 1985: 311–324.

Bernheimer, Charles, ‘Huysmans: syphilis, hysteria and sublimation.’ In Figures of Ill Repute: representing prostitution in nineteenth-century France, Duke University Press, 1997.

Birkett, Jennifer. The Sins of the Fathers, London, Quartet, 1986.

Cevasco, George A. The Breviary of the Decadence: J.K. Huysmans’s A rebours and English Literature, AMS Studies in the Nineteenth Century, No. 25, 2001.

Doyle, Natalie. ‘Against Modernity: the Decadent Voyage in Huysmans’ A rebours.’ Romance Studies, 21, 1992–93: 15–24.

Gasché, Rodolphe. ‘The Falls of History: Huysmans’ A rebours.’ Yale French Studies, 74, 1988.

Genova, Pamela. ‘Japonisme and Decadence: Painting the Prose of A rebours.’ Romanic Review, 88(2), 1997: 267–290.

Grigorian, Natasha. ‘The Writings of J.-K. Huysmans and Gustave Moreau’s Painting: Affinity or Divergence?’ Nineteenth-Century French Studies, 32(3–4), 2004: 282–297.

Hale, Terry. ‘J.-K. Huysmans: Decadent writer or writer of decadence?’ The Goth, Vol. 7, 1992: 4–8.

Halpern, Joseph. ‘Decadent Narrative: à rebours.’ Stanford French Review, 2, 1978: 91–102.

Joradanova, Ludmilla. ‘A Slap in the Face for Old Mother Nature: Disease, Debility, and Decay in Huysmans’s A rebours.’ Literature & Medicine, 15(1), 1996: 112–128.

Knapp, Bettina. ‘Huysmans’s Against the Grain: The Willed Exile of the Introverted Decadent.’ Nineteenth-Century French Studies, 20(1–2), 1991–1992: 203–221.

Laver, James. The First Decadent, Being the Strange Life of J.-K. Huysmans. Faber & Faber, 1954.

Lloyd, Christopher. J.-K. Huysmans and the fin-de-siècle Novel, Edinburgh University Press, 1990.

Lloyd, Christopher. ‘French Naturalism and the Monstrous: J.-K. Huysmans and A rebours.’ Durham University Journal, 81(1), 1988: 111–121.

Loomis, Jeffrey B. ‘Of Pride and the Fall: The Allegorical A rebours.’ Nineteenth-Century French Studies, 12(4)–13(1), 1984: 147–61.

Meyers, Jeffrey. ‘Gustave Moreau and Against Nature.’ In Painting and the Novel, Manchester University Press, 1975.

Mickel, Emmanuel J. ‘A rebours’ Trinity of Baudelairean Poems.’ Nineteenth-Century French Studies, 16(1–2), 1987–1988.

Motte, Dean De La. ‘Writing against the Grain: A rebours, Revolution, and the Modernist Novel.’ In Modernity and Revolution in Late Nineteenth-Century France, edited by Barbara T Cooper and Mary Donaldson-Evans, Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1992.

Nelson, Robert Jay. ‘Decadent Coherence in Huysmans’s A rebours.’ In Modernity and Revolution in Late Nineteenth-Century France, edited by Barbara T Cooper and Mary Donaldson-Evans, Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1992.

Porter, Laurence M. ‘Literary Structure and the Concept of Decadence: Huysmans, d’Annunzio and Wilde.’ Centennial Revue, 22, 1978: 188–200.

Porter, Laurence M. ‘Huysmans’ A rebours: The Psychodynamics of Regression.’ American Imago: a Psychoanalytic Journal for Culture, Science & the Arts, 44(1), 1987.

Roosbroeck, Gustave L van. ‘Huysmans the Sphinx: The riddle of A rebours.’ Romanic Review, 1927.

Seed, David. ‘Huysmans among the British Decadents.’ The Goth, Vol. 7, 1992: 9–13.

Shryock, Richard. ‘Ce cri rompit le cauchemar qui l’opprimait: Huysmans and the politics of A rebours.’ French Review, 66.2, 1992: 243–54.

Storey, Robert. ‘Pierrot-Oedipe: J.-K Huysmans and the Circus-Pantomime.’ French Forum, Volume 6.3, 1981.

Symons, Arthur. ‘The Decadent Movement in Literature.’ Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, No.87, 1893.

Thomas, W E. ‘J.-K. Huysmans and A rebours.’ Modern Language, No.38, 1957.

Weinreb, Ruth Plaut. ‘Structural Techniques in A rebours.’ French Review, 49, 1975.

White, Nicholas. ‘The conquest of privacy in A rebours.’ In The Family in Crisis in Late Nineteenth-Century French Fiction, Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Ziegler, Robert. ‘De-compositions: the Aesthetics of distancing in J.-K. Huysmans.’ Forum for Modern Language Studies, October 1986: 365–373.

Ziegler, Robert. ‘Taking the Words Right Out of his Mouth: From Ventriloquism to Symbol-reading in J.-K. Huysmans.’ Romanic Review, Vol 91, 2000.

Against Nature

I must rejoice beyond the bounds of time … even though the world be appalled at my joy, and in its coarseness knows not what I mean.

Ruysbroeck the Admirable

Notice

To judge by the few portraits preserved at the Château de Lourps, the family of the Floressas des Esseintes had, in days of old, been composed of muscle-bound troopers and grim-faced mercenaries. Squeezed tightly into old frames that barely contained their broad shoulders, they alarmed visitors with their staring eyes, their yataghan moustaches, and their chests, the huge bulges of which were crammed into the enormous shells of their cuirasses.

These were the ancestors, but the portraits of their descendants were missing: a gap existed in the series of faces of this race; a single painting served as an intermediary, forming a link between past and present: a sly, mysterious head with lifeless, drawn features, with cheekbones punctuated by a comma of rouge, with pomaded hair ravelled in pearls, and a taut, powdered neck emerging from the goffers of a stiff ruff.

Already, in this portrait of one of the Duc d’Épernon and the Marquis d’O’s most intimate companions, the defects of a weakened constitution, the predominance of lymph in the blood, had become apparent.

The decline of this ancient line had undoubtedly followed the usual course; the effeminisation of the males became more noticeable, and as if to complete the work of ages, the Floressas des Esseintes had, over the course of two centuries, intermarried their children with one another, using up the remains of their vigour in these consanguineous unions.

Of this family, once so numerous it occupied almost all the territories of the Île-de-France and La Brie, a single offspring was still living: Duc Jean, a frail young man of thirty, anaemic and nervous, with hollow cheeks, blue eyes as cold as steel, a straight nose with flaring nostrils, and slender, desiccated hands.

By a singular atavistic phenomenon, the last descendant looked like a dainty version of his ancient ancestor, from whom he had inherited his pointed beard of an extraordinarily pale blond and his ambiguous expression, at once both weary and shrewd.

His childhood had been dismal. Menaced with scrofula and overwhelmed by persistent fevers, he nevertheless succeeded, with the help of fresh air and careful attention, in cresting the breakers of puberty, and so his nerves gained the upper hand, capsizing the languor and apathy of teenage anemia, and piloting the process of growth through to its full development.

His mother, a tall woman, pale and taciturn, died of exhaustion; in his turn his father succumbed to some malady or other, by which time des Esseintes had reached his seventeenth year.

He had retained of his parents but one fearful memory, with neither gratitude nor affection. His father, who usually resided in Paris, he barely knew at all; his mother, he remembered lying bed-ridden and motionless, in a dark bedroom in the Château de Lourps. Occasionally, husband and wife were reunited, and of these particular days he recalled their monotonous interviews, his mother and father seated opposite one another in front of a round table, which was lit only by a lamp with a large, low-hanging shade because the duchess couldn’t endure light or sound without an attack of nerves; in the gloom, they exchanged a few halting words, then the duke would retire, unmoved, and as quickly as possible jump onto the first train back to Paris.

At the Jesuits, where Jean was dispatched in order to be educated, his life was more convivial and more pleasant. The Fathers prided themselves on pampering this child whose intelligence amazed them; even so, in spite of their efforts, they couldn’t get him to devote himself to the discipline of study; he took to certain subjects, became precociously conversant in Latin, but, by contrast, he was absolutely incapable of construing two words of Greek, showed no aptitude for living languages, and revealed himself to be perfectly obtuse the moment they tried to teach him the first principles of science.

His family hardly concerned themselves about him; sometimes his father would come to visit him at his school: ‘Hello … be good and work hard … goodbye.’ During the summer holidays, he left for the Château de Lourps; but his presence could not drag his mother from her reveries; she barely noticed him, or contemplated him for a few seconds with an almost sorrowful smile, then she would give herself up again to the artificial night in which the heavily curtained windows enveloped the room.

The servants were old and boring. On rainy days the boy, left to himself, delved into books; on fine afternoons he would wander the countryside.

His great joy was to go down the valley as far as Jutigny, a village planted at the foot of the hills, a tiny heap of cottages capped with thatch bonnets scattered with tufts of houseleek and clumps of moss. He would lie in the open fields, in the shadow of tall hayricks, listening to the slapping of the watermills and inhaling the cool breeze from the Voulzie. Sometimes he pushed on as far as the peat-bogs, to the green and black hamlet of Longueville, or even climb the windswept hillsides from where the view was immense. There, on one side below him, he had the valley of the Seine, stretching as far as the eye could see and merging with the distant blue sky; on the other, higher up, near the horizon, the churches and the tower of Provins which seemed to tremble in the sunshine, in the gilded dust of the air.

He would read or daydream, immersing himself till nightfall in solitude; by reason of reflecting on the same thoughts his mind grew sharper and his once vague ideas matured. After each vacation he returned to his masters more preoccupied and more headstrong; these changes did not escape them; perspicacious and astute, accustomed by their profession to probe a soul to its very depths, they were in no way taken in by this newly awakened but untamed intelligence; they understood that this student would never contribute to the glory of their Order, and as his family was rich and seemed uninterested in his future, they immediately gave up the idea of directing him towards any of those schools specialising in the profitable professions; although he willingly disputed with them on all those theological doctrines that appealed to him by their subtlety and their hair-splitting, they didn’t even think to propose him for Holy Orders, because in spite of their efforts his faith remained feeble; as a last resort, out of caution and fear of the unknown, they let him pursue whatever studies pleased him and neglect all the others, not wanting to alienate this independent spirit through the interference of the school’s lay assistants.

He lived like this, perfectly happy, scarcely aware of the paternal yoke of the priests; he continued his studies in Latin and French in his own fashion, and even though theology didn’t figure at all in his curriculum, he completed the apprenticeship he had begun in this science at the Château de Lourps, in the library bequeathed by his great-grand-uncle, Dom Prosper, a former prior of the Canons Regular of Saint-Ruf.

The moment fell however when he had to leave the Jesuits’ institution; he came of age and became master of his fortune; his cousin and guardian, the Comte de Montchevrel, rendered him his accounts. Relations between them were of short duration because there could be no point of contact between these two men, the one being so old and the other so young. Whether out of curiosity, idleness or politeness, des Esseintes visited the Montchevrel family on several occasions, and submitted, in their mansion on the Rue de la Chaise, to some crushingly dull evenings at which his aunts, as old as the world, would interrogate each other about the quarterings of noble arms, heraldic crescents and outdated ceremonials.

Even more than these dowagers, the men who gathered around the whist table revealed themselves as immutable nonentities; here, these descendants of ancient knights, these last scions of a feudal race, appeared to des Esseintes to be catarrhal, finicky old men, endlessly repeating the same dull stories and age-old phrases. Like cutting a cross-section anywhere through the stem of a fern, a fleur de lis seemed to be the only thing imprinted on the soft pulp of their aged brains.

An unspeakable feeling of pity descended on the young man for these mummies entombed in their Pompadour-style catafalques, all rococo and wainscotting, for these gloomy sluggards who were living with their eyes constantly fixed on some nebulous Canaan, on some imaginary Palestine.

After a few evenings in such company, he resolved, in spite of invitations and reproaches, never to set foot there again. Then he began to mix with young men of his own age and from his own class.

Some, educated like him in religious institutions, had preserved the special stamp this education confers. They went to mass, took communion at Easter, frequented Catholic circles, and hid from each other the bouts they indulged in with whores, shamefacedly avoiding each others’ eyes as if it were a crime. They were, for the most part, unintelligent, slavish dandies, successful dunces who had worn out the patience of their teachers, but who had nevertheless fulfilled the latters’ stated aim of populating society with docile, pious creatures.

Others, educated in state colleges or in the lycées, were less hypocritical and more liberated, but they were neither more interesting nor less narrow-minded. They were hedonists, enamoured of operettas and horse-racing, playing baccarat and lansquenet, gambling their fortunes on horses, on cards, and on all those pleasures dear to hollow men. After a year of such trials, des Esseintes felt an overpowering weariness in this company whose debaucheries seemed to him promiscuous and vulgar, carried out with no discernment, no show of passion, and no real stimulation of the blood or nerves.

Little by little he left them and drew closer to men of letters, with whom his mind should have had more affinity and felt better at ease. But this was another delusion; he was revolted by their mean and resentful opinions, their conversations as dull as a church door, and their sickening discussions in which they judged the value of a book according to the number of editions it had gone through and by the profit on its sales. At the same time, he became aware of the freethinkers, the bourgeoisie’s very own doctrinarians, those people who claimed every liberty in order to stifle the opinions of others, greedy and shameless puritans whom he considered inferior in breeding to the cobbler down the road.

His contempt for humanity deepened; he finally came to the conclusion that, for the most part, the world was composed of bullies and imbeciles. Certainly, he had no hope of finding in those around him the same aspirations and the same antipathies, no hope of teaming up with the kind of intelligence that took pleasure, as his own did, in a studied decrepitude, no hope of uniting a mind as keen and intricate as his own with that of a writer or a man of letters.

Nervy, ill at ease and indignant at the insignificance of ideas exchanged and received, he became like those people Nicole talked about, who ‘hurt all over’; he reached the point where he was constantly flaying himself, enduring the jingoistic nonsense and society gossip every morning in the newspapers, and exaggerating in his mind the extent of the success that an all-powerful public always and especially reserves for works written with neither style nor ideas.

Already, he was dreaming of some kind of refined sanctuary, a homely wilderness, a warm, immoveable ark in which to take refuge from the incessant deluge of human stupidity.

A single passion, woman, might have restrained him in the universal contempt that gripped him, but she, too, had palled. He had tasted the feasts of the flesh with the appetite of a capricious man afflicted with bulimia, one who is obsessed by hunger, but whose palate is quickly dulled and surfeited; in the days when he had associated with country gents, he had participated in those protracted suppers during which drunken women unfastened their clothing at dessert and slumped their heads on the table; he had also scoured the wings backstage at the theatre, sampled actresses and singers, suffered, in addition to the innate stupidity of women, the frenzied vanity of third-rate leading ladies; after that, he had kept already notorious whores and contributed to the fortune of those agencies that supply dubious pleasures for a modest recompense; finally, sated, weary of these unvarying lusts, of these identical caresses, he had plunged into the slums, hoping to revive his desires through contrast, thinking to stimulate his deadened senses with the arousing indecencies of poverty.