10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Dedalus

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Intense, meticulously observed impressions of 1870s' Paris

Das E-Book Parisian Sketches wird angeboten von Dedalus und wurde mit folgenden Begriffen kategorisiert:

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Dedalus European Classics

General Editor: Mike Mitchell

Parisian Sketches

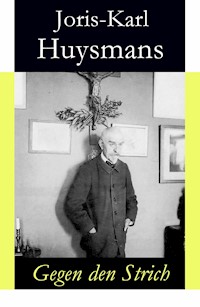

Jean-Louis Forain, La Maison Close. This etching, originally commissioned for the first edition of Croquis parisiens (1880), was one of two that were eventually excluded from the published version.

J.-K. Huysmans

Parisian Sketches

Translated and with an introduction and notes by Brendan King

Published in the UK by Dedalus Ltd,

24-26, St Judith’s Lane, Sawtry, Cambs, PE28 5XE

Email: [email protected]

www.dedalusbooks.com

ISBN 1 903517 24 9

Dedalus is distributed in the USA and Canada by SCB Distributors,

15608 South New Century Drive, Gardena, CA 90248

email: [email protected] web: www.scbdistributors.com

Dedalus is distributed in Australia by Peribo Pty Ltd,

58 Beaumont Road, Mount Kuring-gai N.S.W. 2080

email: [email protected]

Dedalus is distributed in Canada by Marginal Distribution,

695 Westney Road South, Suite 14 Ajax, Ontario, L16 6M9

email: [email protected] web site: www.marginalbook.com

Publishing History

First published in France in 1880

First published by Dedalus in 2004, reprinted 2007

First e-book edition 2011

Introduction, notes and translation copyright © Brendan King 2004

The right of Brendan King to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988.

Printed in Finland by WS Bookwell

Typeset by RefineCatch Ltd, Bungay, Suffolk

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A C.I.P. listing for this book is available on request.

THE TRANSLATOR

Brendan King is a freelance writer, reviewer and translator with a special interest in late nineteenth-century French fiction.

He is currently working on a Ph.D. on the life and work of J.-K. Huysmans. His translations include Là-Bas by J.-K. Huysmans published by Dedalus in 2001.

He lives on the Isle of Wight.

CONTENTS

Introduction

PARISIAN SKETCHES

I.The Folies-Bergère in 1879

II.Dance night at the Brasserie Européenne in Grenelle

III.Parisian characters

The Bus conductor

The Streetwalker

The Washerwoman

The Journeyman Baker

The Chestnut-seller

The Barber

IV.Landscapes

The Bièvre

The Poplar Inn

The Rue de la Chine

View from the ramparts of north Paris

V.Fantasies and forgotten corners

The Tallow candle: a prose ballad

Damiens

Roast meat: a prose poem

A Café

Ritornello

The Arm-pit

Low tide

Obsession

VI.Still lifes

The Herring

The Epinal print

VII.Paraphrases

Nightmare

The Overture to Tannhaüser

Resemblances

Notes

INTRODUCTION

When Croquis parisiens (Parisian Sketches) was first published in 1880, J.-K. Huysmans was in the process of establishing a reputation for himself as a formidable force within the Naturalist school, a group of younger writers with common literary interests who acknowledged Emile Zola as their head. At 32, Huysmans must have felt that he was finally starting to make his mark on the Parisian literary scene after something of a slow start. His first book, a collection of prose poems entitled Le Drageoir à épices (1874), had to be published at his own expense, and though it attracted a little critical attention, its sales were negligible. His first novel, Marthe, histoire d’une fille (1876), had an equally inauspicious start: after arranging to have the book printed in Belgium, Huysmans was stopped by customs at the French border and nearly 400 copies were impounded to prevent ‘an outrage on public morals’. However, enough got through to allow him to send complimentary copies to the writers he most admired, and the book effectively served as an entrée to both Edmond de Goncourt’s grenier and Zola’s Thursday evening literary gatherings. With the contacts he subsequently made through them, his writing career quickly took off: his work began to appear in numerous journals, both in Paris and Belgium, and his second novel, Les Soeurs Vatard (1879), was accepted by Charpentier, Zola’s own publisher. The novel, which included a dedication to Zola from ‘his fervent admirer and devoted friend’, was a succès de scandale and attracted a huge amount of press coverage that inextricably linked his name with that of Zola’s in the public mind. When, early the following year, his short story ‘Sac au dos’ was included in Les Soirées de Médan, a collection of six novellas written by Zola and five of his Naturalist ‘disciples’, including Guy de Maupassant, Léon Hennique and Huysmans himself, his place in the movement seemed assured.

But Naturalism’s refusal to idealise human existence, its insistence that life was subject to inexorable laws of heredity and social conditioning, ensured that it would never find an easy acceptance, either with the public or the conservative press. By 1880, it had become a contentious subject of public debate; the battle lines were drawn, and many of those in the literary press saw the spread of the movement as something that was neither morally healthy or socially desirable. To his critics, Huysmans’ work was, if anything, an even more virulent strain of the new literary disease than that they detected in Zola’s ‘pornographic’ and ‘putrid’ writings. Outraged reviewers of Les Soeurs Vatard complained that he out-Zola’d Zola in his willingness to rub his readers’ noses in the more sordid aspects of contemporary Parisian life:

Emile Zola has produced a school, but as the disciples of the master can’t equal him in talent, they have surpassed him in extravagant obscenities, in Naturalistic ravings.

(Polybiblion Revue Bibliographique Universelle, October 1880)

Another contemporary reviewer of the same book fulminated against the crudity of Huysmans’ descriptions, and his attitude sums up much of the conservative reaction to the graphic nature of Naturalist realism:

Every time the author talks about a pair of boots, they’re oozing and smelling; in describing a gathering of the fairer sex, Monsieur Huysmans tells us about the ladies’ sweat, which recalls ‘the strong fragrance of goats frolicking in the sun’, and then concludes by saying that these odours were mixed with ‘whiffs of tainted pig-meat and wine, with the acrid stink of cats’ piss and the rude stench of the latrine …’! That’s all very well, but I prefer something else.

(L’Evenement, 23 March 1879)

Yet contrary to the common perception among those in the press, Huysmans was not a typical Naturalist – in reality his work was both stylistically and formally at odds with some of the core tenets of the movement – and Parisian Sketches, published just a year after Les Soeurs Vatard, was in no way a work typical of the Naturalist school. In spite of its documentary attention to the details of everyday life, one of the characteristics of Naturalist prose, its literary and stylistic exuberance, its idiosyncratic view of Paris and Parisians, and its fascination with the fantastic and the exotic, show that Zola’s brand of Naturalism could never have contained Huysmans for long. Even Zola seemed to recognise as much when he reviewed the book in 1880:

He [Huysmans] is one of boldest, most unpredictable, most intense virtuosos of language. He has written pages in which Rubens’ village fairs, overflowing with activity, come alive, pages created with a palette of colours and a peculiarity of design that are absolutely original, such as one doesn’t find anywhere else. Really, it’s stupid to think that such a gifted writer needed to attach himself to what has so foolishly been called the Naturalist school in order to make his way in the literary world through shameless pastiche. He was fully formed as a writer when we first met and had already given the measure of his power in pages that were published all over the plac… .

(Emile Zola, La Voltaire, 15 June 1880)

But if Zola read the signs, he certainly did not understand them and a few years later when Huysmans dropped his literary bombshell, A Rebours, the novel that not only radically altered the public’s perception of him as a writer, but also changed the literary landscape of fin-de-siècle France, it seems to have caught Zola unawares. After reading the book, he sent Huysmans a long letter criticising the book piecemeal and ended with the misguided and dismissive prophecy that ‘at least it would count as a curiosity among your other works’ (Letter from Emile Zola, 20 May 1884). As extravagant a departure from the Naturalist path as it seemed to Zola at the time, with its decadent, aristocratic anti-hero who turns his back on the modern world the Naturalists were attempting to critique, A Rebours did not in fact spring fully-formed out of nowhere. As Jennifer Birkett has pointed out, it is possible to see in Parisian Sketches, in embryonic form, many of the themes, motifs and obsessions that would later resurface in Huysmans’ most famous work:

Croquis parisiens, illustrated with engravings by Forain and Raffaëlli, is a clear prelude to A Rebours. The model is Baudelaire transforming the sordid landscape of the modern city with fleeting glimpses of perverse beauty. Grotesque details plucked out from the whole, intensified to dreamlike proportions, turn ugliness into a source of pleasure.

(Jennifer Birkett, The Sins of the Fathers, Quartet, 1986)

Parisian Sketches may be a prologue to A Rebours, but it is also much more than that. Although the first edition of the book appeared in 1880, four years before Huysmans’ decadent masterpiece, the second edition, revised and expanded with the addition of seven new pieces, was published two years after it, in 1886. In that space of time Huysmans had gone from being the rising star of the Naturalist movement to the man who had dealt it a death blow, and this shift is reflected both in the form of the ‘sketches’ themselves and in the changing narrative viewpoint as the book progresses. The book’s opening sketch, ‘The Folies-Bergère in 1879’, vivid and expressive though it is, conforms to many of the conventions of realist prose. In it, Huysmans describes a world that seems to exist physically and objectively, independent of the observer or his state of mind. By contrast, the final pieces in the collection, such as ‘Nightmare’ and ‘The Overture to Tannhäuser’, are written in an allusive style that was to become typical of the Symbolists, a style that attempts to express the feelings and sensations that lie beyond everyday awareness. These virtuoso sketches present a world of subjective impressions, one experienced almost wholly through the individual consciousness of their narrators.

With its six-year gestation period and the inclusion of material that spanned over a decade, Parisian Sketches embodies the transition from Huysmans’ youthful literary interests to the later preoccupations of his mature period. It simultaneously harks back to the prose poems of Charles Baudelaire and Aloysius Bertrand, and anticipates the Decadent and Symbolist movements of the late 1880s and early 1890s; it points forward to A Rebours, but it also points beyond it, to the aesthetic theory Huysmans would later expound under the name of ‘spiritual naturalism’ in Là-Bas (1891), his novel of contemporary Parisian occultism.

Parisian Sketches: the art of writing

Huysmans’ lifelong passion for art was reflected in his writing: his novels, short stories and prose poems are studded with references to specific paintings and artists, and emblematic ‘transpositions d’art’, such as those of Gustave Moreau’s Salomé in A Rebours and Matthias Grünewald’s Crucifixion in Là-bas, are a recurrent feature of his work. Although many writers of the time were also preoccupied with art, this obsession with the image was to a large degree conditioned by the particular circumstances of his childhood. His Dutch-born father, Victor, like his father before him, was an artist by profession and traced his ancestry back to Cornelius Huysmans, one of whose canvases hung in the Louvre. Huysmans was greatly affected by his father’s early death in 1856 and by his mother’s subsequent marriage just a year later to a man he disliked, and it is possible to see in his later adoption of the Dutch form of two of his Christian names (he was baptised Charles-Marie-Georges, but changed his name to Joris-Karl on the title page of his first book), as well as in his self-conscious insistence on his Dutch, painterly heritage, the expression of an oedipal desire to assume his father’s identity.

Huysmans wrote on more than one occasion that he wanted to do with the pen what great artists had done with the brush, and this theme was reiterated throughout his early work: his first major commission as a journalist was a series of descriptive pieces to be printed under the heading ‘Croquis et eaux-fortes’ (Sketches and Etchings); his first collection of prose poems, Le Drageoir à épices, included an introductory sonnet that described the book’s contents as a ‘selection of faded pastels, etchings and old prints’; and with Parisian Sketches he made the metaphorical parallel between writing and art explicit, his punning title alluding to Honoré Daumier’s popular series of cartoons and sketches that had been published in Le Charivari throughout the 1840s, 50s and 60s under the title Croquis parisiens. (When he came to illustrate Huysmans’ story ‘The Streetwalker’, Jean-Louis Forain offered his own hommage to Daumier by adapting and updating his famous sketch on the theme of ‘Coquetterie’.)

Like any collection of prints collected over a period of time, Parisian Sketches, which includes work written between 1874 and 1885, can be divided into ‘periods’ in which the influence of a particular artist or artistic movement can be traced. In the sketches written prior to 1876, the year in which Huysmans first encountered the work of Edgar Degas, the intimist spirit of the Dutch painters of the seventeenth century for whom Huysmans had a profound attachment seems to be to the fore; in those written between 1876 and 1880, it is Degas’ concert-hall paintings and the urban landscapes of the Impressionists that dominate the writer’s visual imagination; and in the final pieces of the book there is a noticeable shift away from the representation of the objective world and an increasing focus on subjective perception, in sketches that are directly inspired by the internalised mindscapes of Odilon Redon.

Huysmans’ discovery of Degas’ work in an exhibition of 1876 marked a turning point in the development of his ideas about art and representation. In his subsequent art criticism, a volume of which was published under the title L’Art Moderne in 1883, midway between the two editions of Parisian Sketches, Huysmans launched a series of vitriolic attacks on academic painting and the conventional art of the Salon: ‘Let’s have art that lives and breathes, for God’s sake,’ he wrote, ‘and into the bin with all the cardboard goddesses and devotional junk of the past!’ Like the Naturalists, the early Impressionists were more often reviled than praised for their innovations, but Huysmans was a fervent advocate of their cause and set about establishing Impressionism as a new artistic paradigm: ‘It is to the small group of Impressionists,’ he wrote in his account of the ‘Exposition des Indépendants’ of 1880, ‘that the honour belongs for having swept away all the prejudices, for having overturned all the old conventions of art.’ His review concluded with a rhetorical flourish, asking how long it would be before Degas was recognised as the ‘greatest painter we have in France today’.

The extent to which Huysmans was influenced by the Impressionists in general and Degas in particular can be gauged from the first four sections of Parisian Sketches. It is impossible now to read such pieces as ‘The Folies-Bergère in 1879’, ‘Dance night at the Brasserie Européenne in Grenelle’, ‘The Streetwalker’ and ‘View of the ramparts of north Paris’ without being reminded of Impressionist paintings that have reached an almost iconic status through mass reproduction: Degas’ Miss La-La at the Cirque Fernando, Manet’s Bar at the Folies-Bergère, Renoir’s Ball at the Moulin de Galette, Caillebotte’s On the Europe Bridge, Monet’s Gare Saint-Lazare, and numerous others.

When he came to look for illustrators for Parisian Sketches, it was almost inevitable that Huysmans would turn to two artists who were closely associated with the Impressionist movement and whom he had praised extravagantly in his Salon reviews: Jean-Louis Forain (a former student of Degas’ who had already provided a frontispiece for the 1879 edition of Huysmans’ first novel, Marthe, histoire d’une fille) and Jean-François Raffaëlli. Both men had distinguished themselves with their etchings, a medium that was more easily reproduced in book form than Degas’ colour pastels, and the first edition of Parisian Sketches included eight plates, four by each artist.

Forain and Raffaëlli were ideal illustrators for Huysmans’ work, their contrasting styles and subject matter perfectly complementing the diverse aspects of Paris that so attracted him. Raffaëlli tended to concentrate on scenes of poverty and neglect, and his landscapes of areas such as the Bièvre and his portraits of destitute or working class Parisians echoed Huysmans’ fascination with suburban decay. By contrast, Forain’s theme was the twin strand of elegance and vice that ran through fashionable Parisian life, and his work focused more on character and the nuances of social situations.

Huysmans’ enthusiasm for the Impressionists did not blind him to other artists, even if their work was antithetical to its ideas, and if Degas’ spirit hovers over the opening sections of Parisian Sketches, that of Odilon Redon hovers over its close. Huysmans had first seen Redon’s distinctive charcoal drawings in an exhibition at the offices of La Vie Moderne in 1881, and the following year he wrote to the artist asking where he could buy prints from the collection Dans le Rêve, after seeing an edition belonging to his editor, Charpentier. Within a short time the two men became close friends, and Redon later recalled that Huysmans ‘always felt at home’ with them during his regular visits to the artist and his wife. Perhaps the defining moment in their friendship was the prose poem Huysmans wrote in February 1885, inspired by Redon’s limited edition set of six etchings, Hommage à Goya. Published first in the Revue Indépendant, it was reprinted in the 1886 edition of Parisian Sketches with only slight changes, under the title ‘Cauchemar’ (Nightmare). Brilliant though Huysmans’ evocations of Redon’s prints are, it must have piqued the artist to see his work adapted and presented – not to say misrepresented – through the medium of another man’s words. Certainly ‘Cauchemar’ reveals more about Huysmans the writer than it does about Redon the artist, and it was as a result of this kind of literary ‘appropriation’ – exacerbated in 1889 by the publication of Huysmans’ second volume of art criticism, Certains, in which he implicated Redon in his own growing fascination with Satanism and the occult – that the two men’s friendship began to cool off by the end of the decade.

Huysmans: flâneur parisien

Amid the popular images of Huysmans the Decadent, Huysmans the Satanist, or even Huysmans the Monk, it is easy to forget that, like his hero Baudelaire, Huysmans was a flâneur parisien, a habitual walker of the city’s back streets and byways, a prose poet of its forgotten corners and neglected alleyways. Particular areas of the city seemed to have a symbolic resonance for him and this was reflected in almost every page of his work, whether in the fictionalised peregrinations of his characters through the city’s streets, in journalistic travelogues such as ‘A travers le Jardin du Luxembourg’, ‘Le Parc Monceau’ and ‘Autour des fortifications’, or in extended studies of particular quartiers, such as La Bièvre (1890) and Le Quartier Notre-Dame (1905). It has been said of Huysmans’ Paris what was once said of James Joyce’s Dublin: that if his native city were to be demolished overnight, it could be rebuilt down to the last brick using his works as a guide. When Walter Benjamin was assembling The Arcades Project, his kaleidoscopic source book to the city he called ‘the capital of the nineteenth century’, he included several lengthy extracts from Huysmans’ descriptions of Paris, all of which were drawn from Parisian Sketches. Huysmans was one of the great nineteenth century writers on Paris, and Parisian Sketches, with its stunning evocation of the city’s streets, its people, its sights and its smells, is a literary tour-de-force inspired by the capital in which he was born and in which he lived almost the whole of his life.