6,84 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

More than a just a journey, Alfredo gives us a blueprint for humane treatment of mental illness

In 1981, twenty-three-year old Alfredo Zotti began his lifelong challenge of living with Bipolar II Disorder. He quickly hit rock bottom, spending time as a homeless person and turning to street drugs and alcohol to medicate his symptoms. After hospitalization and careful outpatient monitoring, he became a successful musician and completed university. In 2004, he started to mentor sufferers of mental illness, and together, they developed an online journal. Alfredo now sees mental illness from a new perspective, not of disadvantages but advantages. In his words: "Having a mental illness can be a blessing if we work on ourselves." In this memoir and critique of mental illness, the reader will learn: How empathic listening and being with someone can help calm that person's symptoms The power of singing to create a safe space in a community Why spirituality can be a key component in the healing process The connections between mental illness, artistic expression, and people who think differently The impact of childhood trauma on our psyche and its role in mental illness The dangers of antipsychotics and antidepressants The amazing connection between heart and brain and how we can cultivate it The challenges of love and marriage between partners with Bipolar Disorder

"Alfredo's story and his insights into the causes and treatment of mental ill-health are incredibly moving and impressive. His humanity, intelligence, creativity and his generosity and compassion towards people affected by mental illness and dedicated mental health professionals shine through the pages of his book."

-- Professor Patrick McGorry, AO MD PhD, Executive Director, OYH Research Centre, University of Melbourne

"As a clinician and academic, one can study and research ever known aspect of a disorder and write scholarly articles for learned journals, but none of this holds the potency of an individual relaying his or her lived experience. Alfredo does just this in his inimitable style, offering hope at every juncture to those who travel a similar road. The story should be read by clinicians, academics and sufferers alike."

--Professor Trevor Waring AM, Clinical Psychologist, Con-Joint Professor of Psychology, University of Newcastle

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 315

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

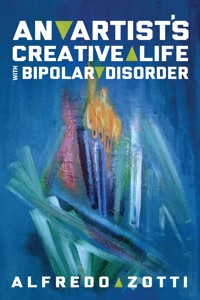

Alfredo’s Journey:

An Artist’s Creative Life with Bipolar Disorder

by Alfredo Zotti

M o d e r n H i s t o r y P r e s s

Alfredo’s Journey: An Artist’s Creative Life with Bipolar Disorder

Copyright © 2014 by Alfredo Zotti. All Rights Reserved.

Learn more at www.AlfredoZotti.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zotti, Alfredo, 1958- author.

Alfredo’s journey : an artist’s creative life with bipolar disorder / by Alfredo Zotti.

1 online resource.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed.

ISBN 978-1-61599-226-3 (epub, pdf) -- ISBN (invalid) 978-1-61599-225-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Zotti, Alfredo, 1958---Mental health. 2. Manic-depressive persons--Psychology. 3. Manic-depressive illness--Treatment. 4. Counseling. I. Title.

RC516

616.89’5--dc 3

2014005085

Modern History Press, an imprint of

Loving Healing Press

5145 Pontiac Trail

Ann Arbor, MI 48105

Tollfree USA/CAN: 888-761-6268

FAX 734-663-6861

Contents

Table of Poems

Table of Drawings and Sketches

Foreword

PART I Alfredo’s Journey

Chapter 1 – Professionals, Sufferers, their Caregivers and the Public

Chapter 2 – The Therapist and the Client: A Matter of Trust

Chapter 3 – Developing Critical Consciousness through Therapy

Chapter 4 – The Therapy Intensifies…

Chapter 5 – In Our Darkest Hour... We Start to See the Light

Chapter 6 – We’ll meet again, don’t know where...

PART II: Treatment and Critique

Chapter 7 – Spirituality and Coping with Mental Illness

Chapter 8 – Liberalism and its Human Nature

Chapter 9 – Clinical and Counseling Psychology

Chapter 10 – The Science and Art of Psychology

Chapter 11 – Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Chapter 12 – Childhood Traumatic Experiences

Chapter 13 – Internal and External Aspects of Multiple Personalities in Bipolar Disorder

Chapter 14 – Antipsychotic and Antidepressant Drugs

Chapter 15 – Creativity and the Creative Artist

Discussion and Conclusion

What Creative Sufferers Have to Say

Chapter 16 – Heart Intelligence and the Creative Process

Chapter 17 – Disability—Don’t Dismiss My Ability

Montmartre and Moulin Rouge

Turn-of-the Century France and Lautrec’s posters

Conclusion

References

References for Counseling and Clinical Psychology

References for Science and Art of Psychology

References for CBT and Social Anxiety

Article and Website

References for Antipsychotic and Antidepressants Drugs Essay

References

Index

Table of Poems

Digital Cities

Rozelle Hospital

Mindfulness

The Forgotten People

Table of Drawings and Sketches

Self-Portrait.

Alfredo (depicted at age 5)

Impression of Bob Rich, PhD.

Sally, the nurse

Rozelle Hospital’s main entrance

The Venetian Tower at Rozelle Hospital

Impression of Cheryl, my wife

“For the Love of Money” (Version A)

“For the Love of Money” (Version B)

The shell of an old tape cassette is now a business card holder.

“The Face of Depression” (my father)

Portrait of a dog

Portrait of Agnes

Morning Mist

Intrinsic Cardiac Ganglion seen through confocal microscope

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Self-Portrait. Drawing by Alfredo Zotti, 2006

Foreword

Alfredo Zotti is a highly unusual person. So, you are about to read a highly unusual book. It is full of wisdom and insight into the human condition in general, and into the joys, tribulations, and challenges of someone who experiences Bipolar Disorder.

To the world at large, Bipolar is a personal tragedy, a form of insanity that attracts stigma and irrational judgment. I was a counseling psychologist for 22 years, and learned that this is a matter of perspective. You can choose to focus in on the condition’s negatives and suffer, or you can do as Alfredo has done, and construct a wonderful silver lining—even a rainbow lining—around the cloud. To Alfredo and me, Bipolar is neither good nor bad, but both. The ups and downs in mood are distressing, and they do impinge negatively on those around the person. However, they also lead to creativity, a different and illuminating view of the world, an opportunity to contribute to the welfare of others.

This is a matter of choice; only most people with Bipolar don’t know they have that choice. If you have Bipolar, or someone important to you does, then you could change your life by following the story of Alfredo’s. I don’t mean that you should copy him, but rather to have him inspire you to stop looking at yourself as damaged.

An internet search will find many highly creative people who have contributed to the betterment of humankind, and who have been diagnosed with Bipolar. There are also historical figures who would have been diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder if they lived now. In cultures other than our own, this was true of many Shamans, seers, and spiritual leaders.

Alfredo is a humble man, who has turned what used to be his affliction into his tool for doing good. For many years now, he has posted on interactive websites, and answered thousands of emails from suffering people, entirely voluntarily. His “payment” has been the joy of giving, the highest form of benefit one can receive.

In this book, he tells his story: how he got to his current situation. As you follow him on his journey, you can enjoy his quirky humor, be stimulated by his insights, and inspired by his achievement. The advice and comment he has sent out individually to so many people is implicit throughout the story. Like he has helped so many people, allow Alfredo to help you.

Bob Rich, PhD

PART IAlfredo’s Journey

1

Professionals, Sufferers, their Caregivers and the Public

This book is written for mental health professionals, such as psychologists and psychiatrists, and also for people who suffer with a mental disorder. It is good for mental health professionals to understand the point of view of the client/patient. It is good for people with similar experiences to be able to identify with someone else who is in the same situation, and yet has built a good life with great satisfaction.

The book is about my experiences, or to be precise, my journey with Bipolar Disorder. Very seldom do sufferers write honestly about their experiences with mental disorders, mostly because of the stigma associated with disclosure. I have come to understand that if we don’t come out of the closet and speak of our experiences, stigma will continue to affect our lives. The best way to fight stigma is adopting complete honesty and transparency so that people learn about us, our feelings, our abilities, and our hopes for the future.

I had a troubled childhood; I have experienced homelessness, have been in a psychiatric hospital—not because of suffering with some serious mental disorder, but because of being homeless—and became a friend to many people with psychoses, such as schizophrenia. I later started to study psychology at a university so that I could better help people with mental disorders online.

Now I have created an online monthly journal. The Anti Stigma Crusaders Journal (ASC) attempts to give an inside view into mental disorders from the perspective of those who suffer from them. Bipolar Disorder can be either a positive force in society or a negative one. It is up to all of us to help sufferers with Bipolar Disorder and other mental disorders as well, so that they may feel included and motivated to contribute to their society.

Many famous people are known to have behaved in ways consistent with a diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder. It would be difficult to include the many names here, but Winston Churchill, Abraham Lincoln, Beethoven, Michelangelo, van Gogh, and many other geniuses appear to have had symptoms and moods consistent with Bipolar Disorder. Research has shown a clear link between genius and madness. I here include a quote, which is from an advertisement made for Apple Computers, written by Rob Siltanen and Ken Segall and narrated by Richard Dreyfuss, who suffers with Bipolar Disorder. I really like the words. If only politicians and affluent people understood the message of the advertisement, the world would be a much better place. It goes like this:

Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently. They’re not fond of rules. And they have no respect for the status quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them. About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things. They push the human race forward. And while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.

This book is divided into two sections: in the first part (my personal story), I write about my past experiences, particularly as an inpatient of Rozelle Hospital in a suburb of Sydney, Australia, and my struggle with mental illness; in the second part (current knowledge of the disorder), I look at my voluntary work in my attempt to help people and myself. What is this thing that we call mental illness? This is what I attempt to answer in the second part of this book.

This is my story and I emphasize “story,” because all humans are storied beings. This means that we make sense of our lives by telling ourselves a story about ourselves. The best that humanity has to offer, in terms of emotions, feelings, hopes, and struggles can be found by reading stories of those who have left us books like To Kill a Mockingbird (Harper Lee), A Room of One’s Own (Virginia Woolf), and Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Paolo Freire). Literature, especially novels and personal stories, can tell us a lot about what it is like to be human. Indeed, I believe that there is a strong connection between good novelists and psychologists and in the future, I would like to see better communication and cooperation between these two professions.

While all of the information presented here is real and accurate, I have introduced in the story the fictional character of “Stella,” who in part represents my mother, whom I lost to bowel cancer when I was 18. She was just 40 years of age and died a few months after surgery, in the early 1980s. She also represents my spirit—that part of me that has become self-critical and that tries very hard to control the child in me, the child that has been so hurt in the past that complete development has not been possible until recently. Stella also represents the best therapists that I have met in my life. Altogether, she is a complex ensemble of help—both self-help and the help of mental health professionals and other good people I have found on my journey.

Stella features in many parts of this first section, and while some readers may find her presence strange or out of place, given that this character is part of my imagination, it is nevertheless important in that it helps me personify that part of my spirit that watches over me and guides me as in the mind watching over itself. I still have a long way to go to fully recover. Indeed, many people do not fully develop and remain slaves of their child selves, which very often causes problems because of runaway emotions, uncontrolled moods, and related problems.

In the story, Stella is my imaginary therapist, a beautiful and intelligent middle-aged woman, who is very compassionate and who, in my mind, can make up for that void inside of me that was created when my parents, especially my mother, abandoned me. They travelled throughout Europe, to work, leaving me behind with various relatives, sometimes for years.

It is true to say that while we all have many different aspects to our personalities, we also have a parent, a child, and a self personality. These aspects of personality are sometimes well-integrated to make a person really whole and these people often find happiness and stability in life. But for many of us, who suffer with a mental disorder, these three aspects of personality are not well integrated and are sometimes detached from each other. In Dr. Thomas Harris‘ book I’m OK, You’re OK: A Practical Guide to Transactional Analysis (1969), he wrote extensively about the child-parent-self aspects of personalities. I think that this book is still very relevant to those who suffer with Bipolar Disorder or depression and probably all mental disorders.

What I can say, after writing this book, which is an account of my journey as someone who suffers with Bipolar II Disorder1, is that I am learning to cope with the disorder. Indeed, my portrait is not on page vi because of vanity, but because it indicated an attempt to look at my spirit closely, just like someone looks at one’s face in the mirror. Not only am I learning to cope with Bipolar Disorder, but I also use it to fuel my creativity and to help others.

I help other sufferers by writing on many websites. However, I am not always received well by the members of self-help websites who suffer with mental disorders, such as Bipolar Disorder, Major Depression, Dysthymia, Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), or Schizophrenia, to name a few. I think that I have the tendency to expose very difficult and sensitive issues that many sufferers like to avoid. I know that the only way to develop, to integrate our child personality with the rest of us, and to become able to control our disorder is by being completely transparent with ourselves, to have courage and to have the ability to be self-critical, the kind of self-criticism that Paolo Freire, the famous Brazilian educator, called “Critical Consciousness.” I don’t necessarily help people on websites by agreeing with them and by trying to make them feel better. Of course, I try to do this whenever possible; but my real intention is to awaken the critical consciousness so that a sufferer can start to liberate their soul and possibly begin to find their way in the Universe. Some become annoyed and distance themselves from me. That is fine; but others continue the dialogue with me, and together we often make good progress in terms of understanding our mental disorder.

What I am trying to answer in this book is this: What is Bipolar Disorder? I can only answer (and I will answer it at the end of the book) by relying on my personal experience, knowing that it may not apply to everyone’s story: I was just a very sensitive and creative child. This is not a genetic defect but a genetic gift. Because of being sensitive, when my parents abandoned me, Bipolar was triggered. For me, it is not a genetic problem, unless being talented and sensitive is a problem. In my case, it is an emotional problem, a kind of anguish that never goes away. This anguish causes symptoms that very often accompany us throughout life.

People like me may need medication to deal with the emotional problems, symptoms, and moods; but the fact remains that we have no proof that mental disorders, even the most serious ones, are purely genetic or biological. There will always be genetic, biological, and environmental factors at work and, for this reason, we need to treat mental disorders by using a bio-psychosocial approach—that is, to attend to biological, social, and psychological problems.

I fear that this is not always the case today, where many people opt for medication first, forgetting how difficult it is to control Bipolar and what it really takes to get better. In my opinion, the mind can be a powerful tool in the control and maintenance of our disorder, but the problem is that because of ideology and various other social problems, many of us are unable to help ourselves and tend to give up.

Genes can be switched on and off in the environment, but emotions and fears need to be understood, controlled, helped, and released when the time is right. For this, there is a need for extensive therapy and the “will” of the sufferer to participate in the therapy, to be willing to face up to memories and facts that may be painful. The aim should always be to develop resilience.

For example, mania in Bipolar Disorder is a kind of overconfidence in the face of disaster. As Michael Corry and Ann Tubridy once wrote in their book, Going MAD? Understanding Mental Illness (2001), it’s like rearranging the deck chairs of the sinking Titanic and even inviting people to continue the party while the ship is about to go down into the deep ocean. It is partly fear of failure. Depression can be the opposite, or fear of living and the desire to give up. Medication can help a person sometimes, although very rarely, even for life; but it is like using crutches to walk while others can learn to walk without them. Some can learn to cope without medication.

To get to the bottom of the problems, however, we have to deal with emotions, and this requires that both the sufferer and the therapist enter into a very deep and honest dialogue with the intention of changing the personality to a more resilient one. That is why I am a fan of humanistic psychology and an admirer of the late Carl Rogers‘ theories. Unfortunately, one-size-fits-all methods will not do, so good psychologists have to rely on the best that theories and methods have to offer. I am proud that I have been able to confront my problems and my past in the attempt to rationalize the problems so that I can become in control, rather than be controlled by runaway emotions based on non-factual fears. Some irrational thoughts will always be there, but I am aware of them and I can do something about them. That is the development of critical consciousness, or the mind watching over the mind.

I write my story much as a writer would write about other people. In this sense, I try to look at myself from a distance. To what extent I’ve succeeded, I cannot say.

1Bipolar II Disorder is characterized by at least one episode of hypomania and at least one episode of major depression. Diagnosis for Bipolar II disorder requires that the individual must never have experienced a full manic episode (one manic episode meets the criteria for Bipolar I disorder). Berk, M. & Dodd, S. (2005)

2

The Therapist and the Client: A Matter of Trust

Stella Ferguson is an attractive, motherly, middle-aged woman. She is a therapist and also a multi-talented person. She was playing piano at the age of six and is also a visual artist. She writes poems and has published a number of self-help books. Her clients are mainly wealthy people but she does bulk bill (meaning that she charges the government at a lower hourly rate to treat poor people).

I remember the first day when I went to therapy. Stella was sitting on her comfortable black leather armchair, resting her chin on her fist while taking a break from her busy day, probably in an attempt to give her busy mind a break. Nat King Cole was quietly singing in the background, “There will never be another you,” and the blinds were semi-closed, letting little sunlight through the windows. I was to become one of her clients, but also a good friend.

There was no infatuation or romance between Stella and me. We respected each other, almost forgetting that we were the opposite sex, and built a strong and transparent friendship, something that I feel is necessary for successful therapy to happen. In fact, the most powerful thing in therapy is friendship. In my opinion, ditch the Watsonian and Skinnerian ideology about behavioral modification, more suited to animal training than people. Instead, embrace the ideas of Carl Rogers and his unconditional respect for the client, and let the client find their own way, without pressure, in an atmosphere of friendship. Our mutual respect was due to the fact that we are both gifted in many ways. Both Stella and I are married to other people and our relationship was a rare friendship that was taking us on a journey of self-discovery and self-awareness.

The initial therapy sessions were quite formal and it took me quite a while to open up. I could discuss other people’s problems quite easily, but not mine. Stella seemed quite frustrated about it because, as she told me, I desperately needed to let my emotions out and this could only happen if I found the courage to confront my traumatic past. As the sessions and the months went by, I found myself able to open up and begin to tell my life story, something that I found very therapeutic.

While Stella was thinking, she suddenly felt emotional, reaching for the tissue box on the little table near her (usually it is the client that cries and reaches for the tissue box). She told me that what had brought up the emotions was her recollection of the sixth session she’d had with me, a session that I will never forget. Stella recalled the drawing that I had shown her in one of our sessions, which I had made when I was about six years of age. It was the drawing of a lonely child, sitting on a huge chair in the middle of a large, empty room. This symbolized the tremendous void inside me that had built up because I had been abandoned—a void that, as I told her, would never be filled.

Alfredo (depicted at age 5)

I had told Stella about my interest in childhood traumas. Because of my volunteer work online, in my attempt to help people in all corners of the world, and with the help of counseling psychologist, Dr. Bob Rich, I had come to understand that what we call mental illness is mostly triggered by traumatic experiences. I believe that about 80 to 85% of all mental illness in the world is due to trauma, especially childhood trauma; and the people I helped online were and still are confirming this. Hundreds of people had experienced some sort of trauma, mostly during childhood, and sometimes in adulthood. Sometimes sufferers were aware of the trauma; but at other times, they were not. The interesting thing is that the traumatic experience would surface sooner or later. I had shown Stella many emails of sufferers who were telling me the stories about their childhood traumas. Here is what a young woman told me and we later found out that she had, indeed, experienced childhood trauma:

I don’t think there is a cause for my depression and psychosis. I was sexually assaulted at 16 and my mother was an alcoholic who suffered with Bipolar Disorder, and she was abusive and violent. But there does not seem to be any ongoing trauma from that.

I consulted my friend Dr. Bob Rich, who is a counseling psychologist, and he wrote:

That kind of pattern makes me strongly suspect repressed severe trauma. She should go to a good therapist and do age regression hypnosis. If there is trauma, and she recalls it, she can deal with it and get rid of the problem sometimes for life. It usually feels too scary to do. I say to my clients: there is a box there, and you are working hard to keep the lid on. But what’s in the box is not a monster. It’s the photograph or movie of the monster. A photograph or movie cannot hurt you; only remind you of the past hurt.

Stella was very interested in my research and I could see that she enjoyed discussing my emails and the fact that I attempted to help so many people from all corners of the world. If nothing else, my care and company were therapeutic to many sufferers with mental disorders. It was that special friendship that we had built over time that really helped both me and the person I was trying to help or comfort, simply by listening without judgment and only giving advice if I had experience of the problem from a non-authoritarian position, the position of an equal sufferer. This worked very well. Of course, it did cause confrontations at times and sometimes the friendship was affected to the point that it had to be discontinued. But I feel that confrontation is good, just as much as support and agreement, because it stimulates the person to think and to change, even if this happens at a later date.

Change does not happen without some struggle, and verbal confrontation is a way in which people can unload their bottled-up emotions and feelings. Many unpleasant things have happened to me and at times, I have had to abandon some websites for disturbing their “peace” with my thought-provoking ideas. Sometimes I was banned from sites for demanding transparency and freedom of speech; but most of the times, I have been welcomed and achieved good things. I feel that this was all valuable effort because people tend to reflect on things even after such a confrontation. Such confrontation often brings to the surface childhood traumatic experiences.

Stella told me that she was in agreement with Dr. Bob Rich and now that she got to read the research that I had completed, she was really beginning to think of the possibility that childhood trauma could possibly make up most of what we call mental illness. After all, the majority of her clients (about 85%) had experienced childhood trauma, as she told me.

It was unreal for me to find that all of the sufferers with whom I was in contact would sooner or later identify their trauma simply by communicating with me openly. Perhaps my art served to break the ice. Or maybe it was my very open nature. My friendliness and openness emerged because of my own trauma. I had such a void inside, caused by the separation anxiety that I needed to communicate with people at a deeper level as much as possible. Communication was helping me and it was also helping others. The sharing of my art was a special thing for me. I loved to share my poems, my visual art and my music with people.

Even Stella found the poem that I had written and given to her, expressing how I felt while attempting to help others online—interesting and touching. I loved to share my creativity with Stella, who well understood me because she was aware that I expressed myself not only with words but also with poems, visual art, and music. Stella loved my art and she encouraged me to share it with her, to show her all that I did. This was part of the therapy. Here is the poem that I gave Stella to read:

Digital Cities

Journey through the digital cities of broken dreams,

wandering along the sites of sorrow

trying to touch the quantum hearts

that travel through the phone-lines.

The journey is long, the dream worth it.

To all the broken hearts who hide behind their anguish

my message is one of hope and love.

Hide no more and show your heart

for only then will your broken dreams turn into hope.

It was my visits to various websites that helped me realize that I needed help and that I could possibly find this help simply by communicating with other sufferers. We had a special understanding and insight into our disorders that many experts did not have or understand. Over the years, I have collected many emails from sufferers, which I have filed on computer and which I often read. Here are some of the emails:

Alfredo, you asked why I thought people aren’t forthcoming about sharing childhood experiences of abuse. I was thinking about that and realized that I didn’t even think I had been abused until I was about 40. I always thought the depression was biochemical or the fault of someone or something else. Even then, there was a lot of shame just because of the thought of speaking ill of one’s parents, or “blaming” them. I could always hear my mother’s voice in my head whenever I thought or felt anything negative about her or my dad. Therapy has helped a lot with that and only in looking back can I see what I didn’t know then.

My research, a questionnaire to over 100 therapists (out of nearly 2000 I had contacted worldwide), resulted in an estimate that childhood trauma makes up an average of 75% of all mental disorders. The therapists unanimously agreed that childhood trauma makes up a great percentage of all mental illness. In other words, stop the trauma and many would not develop a mental illness. Perhaps, without childhood trauma, mental illness as we know it would be a thing of the past. And while some people develop a mental illness due to mild trauma, sufferers usually have a history of severe and repeated trauma like physical abuse, sexual abuse, or other serious experiences. Indeed, I was fortunate to have helped people with severe Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). I even wrote a song about a friend who later recovered but still suffers with some symptoms of schizophrenia. Here are the lyrics of the song which I wrote and gave Stella to read:

Daisy was only 17 when she came to me.

She had swollen lips and a bloodied shirt.

Daisy tried to speak to me but her voice just failed.

She’d been raped by her old man,

he’d been riding her for some time.

Daisy came to me with swollen eyes,

she had been crying all day long, and she said:

“What do I do now? What do I say?

I can’t go on this way, I can’t go on.”

And I said: “Daisy, you must pick up the pieces,

you must go on now, I’ll help you all I can

I’ll stand by you.”

So we went to the police to tell her story, and I could see,

Daisy would never be the same again.

In one session, Stella asked, “Is our world toxic to our children? Are we making our children sick? Are we creating mental illness in the process?” These are the kinds of questions that your research is bringing up in my mind, Alfredo.” She read another email that my friend Judy had sent me and reading this increased her concerns:

Alfredo, I really do agree with you here and I have asked myself this same question many times—What do we do? It is so frustrating to see this cycle of child abuse go on, generation after generation. I think those of us who are dealing with our depression or whatever have been able to see where it comes from and to try to heal ourselves and, hopefully, make sure we don’t keep passing this on. Those who hurt us were also hurt as children, I believe.

But there is still that stigma among many about mental illness, so nobody wants to talk about it or about their abusive childhoods; so people still remain ignorant about what effect it has. I think most criminals have also most likely suffered some kind of abuse or mistreatment in their lives. I guess I would rather be depressed than be a murderer, but think of all the suffering we could avoid if we could stop the mistreatment of children. A lot of people don’t even recognize abuse when they see it; we’ve gotten so immune to it. They don’t realize that words can hurt us, a lot of times worse than any physical punishment. I know that as a child, I sometimes would wish my dad would just hit me and get it over with, rather than rant on and on about how stupid and disgusting I was; we all were.

What do we do? Right now, I’d say we do what we are doing—trying to heal ourselves so that we can keep our children from having to suffer because of our pain. Somehow, I wish we could bring this subject out into the light where everyone could see it and people could be educated so that if they suspect it is happening to a child they know, they may step in. It’s so widespread, it’s easy to feel despair; but it’s just like so many other things—we can just do it one step at a time. I think you’ve brought up a very important topic—I know it’s not the first time you’ve talked about it, but you asked the question: what do we do??? We need more answers.

Stella was coming to understand, while helping me, that childhood trauma is much neglected and that society needs to pay more attention to it if we are serious about reducing mental illness. Prevention is better than cure. Let’s reduce childhood trauma and put most of our world resources in doing this, rather than focusing exclusively on spending money on drug research and various other things that seem to fuel mental illness rather than check it. In many ways, I feel that we are creating mental illness in our world.

“My God,” Stella said, “if childhood trauma is what causes most mental illness, then we are covering this up subconsciously, blaming the whole thing on biological defects and genetics. That is what we are doing. We are basically saying that mental illness is a biological/ genetic problem even though we know that it is much more complex than that and that many call for a bio-psycho-social approach. But our actions don’t seem to support the bio-psycho-social model.”

Stella was aware that I was not in agreement with Scientology, which is totally against any kind of medication. No, not at all, because I know that medication can save lives. After all, my wife suffers with Bipolar I2 and she does need medication, every day. At the same time, the practice of medicating people when they do not need it is still a problem. Medication can also be harmful and the world needs to be more cautious about the greed of pharmaceutical corporations and their influences in universities and government organizations. Much research is ringing alarm bells. There is evidence to suggest that childhood abuse affects a great number of our children. A survey from my personal longitudinal research of nine years has revealed that about 75% of sufferers, out of a sample of over 700, have endured traumatic experiences during their childhood. For example, many people who suffer with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) report having had a history of abuse and neglect. Many studies support these claims, as we will see in the second part of this book, and that childhood trauma is a risk factor for a diagnosis of Schizophrenia, Major Depression, Personality Disorders, and Bipolar Disorder later in life. Some research indicates that childhood trauma is a causal factor for the development of psychosis and schizophrenia.

Taking medication does not mean that mental disorders are necessarily a purely biological dysfunction. We don’t know yet. This is the chicken and egg question: is there an initial genetic defect, a predisposition, where a traumatic environmental event triggers a mental illness? Or is it the trauma that changes biological functions? And what about, as I often suggest, the possibility that some people are much more sensitive and creative than others (meaning that this cannot be seen as a genetic defect) and, therefore, develop a mental disorder because of their sensitivities? Indeed, many of these sensitive people often gravitate to the creative professions so that they can do therapy through their work. These are the helping professions. After many discussions, I sensed that my concerns for people with mental disorders and childhood trauma had struck a major chord with Stella. There was such overwhelming evidence that childhood trauma causes mental illness! And with the statistics giving such alarming figures, it was not difficult to speculate by an informed and educated position that childhood trauma made up most of what we call mental illness today.

2Bipolar I disorder sometimes occurs along with episodes of hypomania or major depression as well. It is a type of Bipolar Disorder, and conforms to the classic concept of manic-depressive illness, which can include psychosis during mood episodes. The difference with Bipolar II disorder is that the latter requires that the individual must never have experienced a full manic episode - only less severe hypomanic episode(s). Berk, M. & Dodd, S. (2005).

3

Developing Critical Consciousness through Therapy

Alfredo: “I am sorry Stella, I’m a little late.”

Stella: “Come in Alfredo. Sit down, please. What’s been happening lately?”

[That is the question I was to hear every time I went to therapy. Yet I knew that what had been happening lately was always a roller coaster of moods, symptoms and inner pain, something that I have learned to live with. It never goes away and it has become part of my personality; those of us with severe mental disorders simply learn to live with it, but I think that the idea of a plastic brain is also overrated. The brain is plastic, but it is not always possible to change behavior and thoughts that have been established over many years. It is not as simple as that.]

Alfredo: “Well, I have been thinking about my past, Stella. My life has been full of traumatic experiences and my mind is fragile now, even though, as the years go on, I become wiser and more resilient. But I feel that my mind is very delicate. I must be careful. I’ve got to take it easy with everything I do and my focus is on striking a balance.”