Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: IMM Lifestyle Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

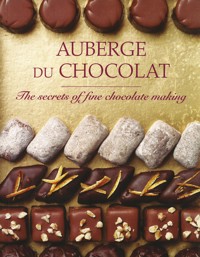

Chocolate - irresistible to so many of us - has gone upmarket, with chocolate shops full of the most beautiful confections. Luckily, creating mouth-watering confections at home no longer requires hours of training and this book will teach you all the inside tips, techniques and methods for making chocolates like a professional chocolatier. Using ingredients such as strawberries and cream and espresso, to the more adventurous flavour combinations such as jasmine and rose, chilli chocolate, rosemary and thyme and white chocolate and cardamom, you will learn how to make fabulous chocolates to suit any taste. There are also recipes for a range of dairy-free chocolates and a collection of chocolates that even the youngest children can help to make. With chapters on the history of chocolate as well as a comprehensive section covering ingredients and equipment and techniques such as melting, tempering, making molds and gift-wrapping your chocolates, this is the perfect book if you want to dazzle your friends and family with delicious chocolate gifts.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 116

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AUBERGEDU CHOCOLAT

___________________________

The secrets of fine chocolate making

AUBERGEDUCHOCOLAT

___________________________

The secrets of fine chocolate making

New Holland

First published in 2011 by

New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd

London • Cape Town • Sydney • Auckland

Garfield House, 86–88 Edgware Road,

London W2 2EA, United Kingdom

www.newhollandpublishers.com

80 McKenzie Street, Cape Town 8001, South Africa

Unit 1, 66 Gibbes Street, Chatswood, NSW 2067, Australia

218 Lake Road, Northcote, Auckland, New Zealand

Text copyright © 2011 Anne Scott

Photographs copyright © 2011 New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd (except those listed here)

Copyright © 2011 New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders.

Anne Scott has asserted her moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Print ISBN: 9781780094595eISBN: 9781607654155

Senior Editor: Lisa John

Photographer: Edward Allwright Production: Laurence Poos Design: Penny Stock

Publisher: Clare Sayer

Reproduction by Modern Age Repro House Ltd, Hong Kong

This book contains chocolates made with raw eggs. It is prudent for pregnant or nursing mothers, invalids, the elderly, babies and young children to avoid uncooked eggs. This book also includes chocolates made with nuts and nut derivatives.

Contents

All about chocolate

Chocolate techniques

Presentation

Chocolates

Dipped chocolates

Truffles

Moulded chocolates

Flavoured chocolate

Dairy-free chocolates

Chocolate and children

About Auberge du Chocolat

Suppliers

Acknowledgements

All about chocolate

Chocolate has been eaten and enjoyed for hundreds of years. Understanding more of its intriguing history and the processes by which it is made can only enhance your enjoyment of making and eating it.

The History of Chocolate

The history of chocolate is full of myths and mystery and sometimes it can be hard to separate fact from fiction. What follows are generally perceived to be the basic facts.

FOOD OF THE GODS

The earliest records we have of chocolate date back some 1500–2000 years ago in the Central American rainforests. Here we find the Cacao tree, worshipped by the Mayan civilization. Cacao is Mayan for ‘God Food’, which later gave rise to the modern generic Latin name of Theobroma cocoa, being ‘Fruit of the Gods’. Although we might agree with the sentiment behind the name, this is certainly not a form of chocolate that we would recognize today. The Mayans produced a spicy, bittersweet drink made by roasting and pounding the cocoa beans and then adding maize and capsicum. This was then left to ferment. This very special drink was used in religious ceremonies and by the very wealthy. It is also thought to be something only men were allowed to drink, as one of the properties attributed to the drink was that it was a powerful aphrodisiac. It was thought that allowing women to drink it would give them all manner of ideas above their station.

The cocoa bean also held significance for the Aztecs. Unfortunately, their climate and land did not lend itself to the cultivation of cocoa trees and this may have given the beans an even higher value. Beans were used as a currency and it is reported that 100 beans could buy you a slave.

The Mayans made a chocolate drink by pounding the beans from a cocoa pod.

As they were unable to grow the beans, the Aztecs obtained them through trade or the spoils of war. As well as needing the beans for currency, the Aztecs made a similar drink to the Mayans. Like the Mayan Cacao, the Aztec Xocolat was linked with religion and the supernatural. According to legend, their creator and god of agriculture Quetzalcoatl arrived on a beam of the morning star, carrying a cocoa tree from Paradise. Wisdom and power came from eating the fruit of the tree. The value given to Xocolat can be seen in the description of the drink by Emperor Montezuma, who reportedly drank Xocolat 50 times a day: he is supposed to have said that the divine drink ‘builds up resistance and fights fatigue. A cup of this precious drink permits a man to walk for a whole day without food.’

MORE THAN JUST A DRINK

In 1519 the Spanish conquistador Henri Cortes found cocoa beans while ransacking Aztec treasure stores. He realized the beans had commercial value and took them to Spain where a drink more suitable for the European palate was eventually produced by mixing the powered roasted beans with sugar and vanilla. Chocolate remained highly valuable and its origins were kept secret in Europe for almost a century. So much of a secret that in 1579 when some English buccaneers boarded a Spanish treasure galleon and found what looked like ‘dried sheeps’ droppings’, rather than the gold and silver they’d expected, they set fire to it in frustration. Traders in Europe eventually discovered Spain’s secret and chocolate soon became available throughout Europe.

Shown here top left, Quetzalcoatl is often depicted holding a cocoa bean or cocoa tree.

In 1520 chocolate arrived in England and it rapidly became all the rage. In 1657 London’s first chocolate house, the ‘Coffee Mill and Tobacco Roll’, opened and the new chocolate drink quickly became a bestseller. Clubs built up around the drinking of chocolate and many a business deal was conducted over a cup. Chocolate houses were in effect the forerunners of today’s popular coffee houses. As chocolate became more sought after, politicians imposed an excessive duty of 10–15 shillings per pound (comparable to approximately ¾ its weight in gold). This made chocolate very much a luxury item and therefore something to be enjoyed by the aristocracy and the business community. It was nearly 200 years before this duty was dropped.

Chocolate houses sprang up all over Europe selling a popular chocolate drink. This was eventually sold to make at home.

FROM DRINK TO MILK CHOCOLATE BAR

The next main event was the production of the first chocolate bar. In 1828 Dutch chemist Johannes Van Houten wanted to make a smoother, more palatable chocolate drink so invented a process to remove the cocoa butter from the cocoa beans. This paved the way for production of chocolate as we know it today. In 1847 the Fry & Sons factory in Bristol, a family-run business that had been making chocolate since the mid-18th century, used the Van Houten process to add sugar and cocoa powder to the extracted cocoa butter and were thus the first to produce a chocolate bar fit for widespread consumption. In 1875 Daniel Peter, a Swiss manufacturer, then further developed the chocolate bar by adding milk powder to the mix, thereby creating the first milk chocolate. Earlier attempts to make a milk chocolate had used liquid milk but this did not combine well with the other ingredients and soon turned rancid. Peter, after years of experimentation, was in the end inspired by his neighbour Henri Nestlé’s invention of condensed milk, which Peter used to make milk drinking chocolate, and farine lactée, a milk food he used to feed his own daughter.

The first chocolate bar was produced in the mid-19th century and changed the way the public enjoyed chocolate.

How Chocolate is made

All chocolate starts life as a cocoa pod. Although cocoa pods come in various colours, shapes and sizes, most are the size and shape of 25–30 cm (10–12 in) rugby ball. These are cut from the tree, slashed open, the flesh scooped out and the many small fruits piled onto a plantain leaf mat. Here they are left to ferment for up to seven days, depending on their quality, in order to take on their chocolatey flavour. Ideally, they are then left in the sun to dry but in a rainforest climate, roll-on covers can be used, or the fruits can be dried in an oven, a process that unfortunately can affect the flavour of the chocolate. The farmer will then sort and bag his crop and sell it to international buyers.

ROASTING AND SEPARATING

The conditions under which the cocoa is grown affect the taste of the final chocolate but so do the processes used at factories. The beans are roasted at 120–140°C (250–275°F) for long enough to bring out their wonderful intense flavour but not so long that they end up burnt. This is where the skill of the roaster comes in. The outer layer of the bean is then removed (and used in gardens as ground cover and decoration), in a process called winnowing. This leaves behind the cocoa nibs.

Cocoa pods are cut open to reveal a fleshy interior, containing many fruits or cocoa beans.

Once dried and roasted, the outer layer of the bean is removed to leave cocoa nibs.

Cocoa nibs are finely milled to create cocoa liquor, some of which is then pressed to extract cocoa butter, leaving behind a solid mass called cocoa presscake. This presscake undergoes further processes in order to produce cocoa powder.

MIXING AND CONCHING

One of two processes then occurs depending on exactly what type of chocolate is being made. Ever since Hershey discovered how to remove cocoa butter from chocolate in order to make it more suitable for soldiers’ ration packs in the Far East during the Second World War, we’ve had two types of chocolate. The first is made very quickly. It takes only about 12 hours to make: the cocoa butter is removed and replaced with hydrogenated vegetable fats. The second type, valued among chocolate connoisseurs, undergoes a much longer process. Cocoa butter is added to the cocoa liquor, along with sugar and, in the case of milk chocolate, powdered milk. The chocolate is then passed through granite rollers at about 50–80°C (120–180°F) in a process known as conching, which is a kneading and smoothing process. The fineness of the chocolate is determined by how long it remains in the conch. The resulting chocolate melts in the mouth without leaving a cloying taste and is considered a far superior product to the chocolate produced using vegetable fats.

In order to achieve a fine-quality chocolate, the chocolate must be conched.

Where Chocolate is grown

Cocoa is grown in a band of 26° either side of the Equator. The trees won’t just grow anywhere; they require constant warmth and rainfall. Even this won’t work if there is not enough shade and nutrients. Approximately 70 percent of the world’s cocoa beans come from Africa – the Côte d’Ivoire alone produces about 1.4 million tons of beans a year.

TYPES OF COCOA BEAN

Most of the African beans, however, are a common type of bean known as Forastero, which are grown for bulk, not quality. Ghana is the world’s second-largest producer of cocoa beans with over 600,000 tons per year. Cocoa is also grown in Indonesia, Brazil, Venezuela, Ecuador, Togo, Mexico and Papua New Guinea and other Latin American countries and in the Caribbean. Generally the cocoa beans grown in Latin America and the Caribbean are considered to be better quality, although some very good beans come from Africa. Traditionally the most flavoursome beans are of the type known as Criollo. They are red, elongated, somewhat fragile beans with flavours of raspberries and citrus. These account for less than 5 percent of cocoa production. In the eighteenth century a hurricane caused natural cross-pollination of the Criollo and Forastero beans, giving rise to a hybrid called Trinitario with a great flavour of apples, oak and balsam. This bean and other hybrids can produce excellent flavour and robustness.

Different types of cocoa bean are grown to satisfy demand either for bulk or for quality.

SINGLE-ORIGIN AND SINGLE-ESTATE CHOCOLATE

Where the cocoa is grown, the weather conditions, the soil and the farming methods all affect the taste of the beans produced – rather like the concept of terroir in wine. As people become more and more excited about quality chocolate, there is a movement towards eating more single-origin and single-estate chocolate; that is chocolate made from beans grown in one particular area or plantation. As you get more involved in discovering and devising your own chocolate recipes, you might also like to experiment with this.

Cocoa is grown in a band close to the equator, where the need for warmth and rainfall is easily met.

CHARACTERISTICS OF SINGLE-ESTATE CHOCOLATES

You may wonder if chocolate tastes any better if made from single-origin or even single-estate beans. Taste is, of course, a personal thing but the big difference you will notice is the complexity of flavour. As with wine, you will taste different flavour notes and levels. This increase in complexity will obviously increase the depth and excitement of your chocolates.

For example, if you are making a tangerine truffle or ganache then it could be worth experimenting with using a Madagascan coverture. The Madagascan coverture has light citrus flavours a bit like tangerine. Or try using Ecuadorian coverture, which has jasmine flavours. If you want something really fruity use a couverture from Venezuela, as this evokes the flavours of ripe red plums and dark cherries.

Other single-origin flavours you might like to try are those from Trinidad and Tobago, which are fruity but with spicy, often cinnamon, flavours. Jamaican chocolate is usually bright and fruity with a subtle pineapple flavour.

Another great way to use single-origin chocolate is simply on its own. It is excellent made into thins for the perfect end to a meal (see here for method).

Every single-origin chocolate tastes different so do experiment to find your favourites and to make your chocolate-making more interesting.

BLIND TASTING