Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: IMM Lifestyle Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

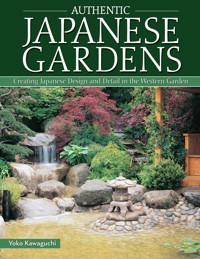

This beautifully illustrated book provides an inspirational and practical introduction to the traditions of Japanese Zen gardens, using natural materials such as wood, bamboo, rocks and pebbles. Emphasizing the value of shape in trees and shrubs with the subtlety of color through the varied greens of foliage and moss, Authentic Japanese Gardens explains how western plants and materials can be used to achieve peaceful, contemplative gardens. There are instructions and tips for selecting plants and materials that are readily available, as well as plant lists and climate zone maps to aid western gardeners. As the wealth of stunning color photographs from around the world demonstrates, Japanese garden design is concerned with a reverence for nature and the overall effect is of tranquility. Authentic Japanese Gardens will help people to create much-needed oases of calm in their own outdoor spaces.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 241

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Introduction

Chapter one

Traditional Japanese Gardens

Historical context, design, choice of plants

The hill and pond garden

The dry garden

The tea garden

The courtyard garden

Chapter two

The Elements of a Japanese Garden

How to choose, lay out and care for the components of a Japanese garden

Plants

Rocks

Water

Sand

Paths and stepping stones

Bridges

Stone lanterns

Pergolas

Fences

Borrowed vistas

Chapter three

Plant Directory

Trees

Shrubs

Berries

Groundcover

Grasses and bamboos

Mosses

Ferns

Tropical specimen plants

Foliage and flowers

Aquatic plants

Non-traditional alternatives

Resources

Hardiness zones

Bibliography

UK Gardens to visit

General index

Index of plants

Photography credits and acknowledgements

A kasuga-style lantern stands watch over a teahouse built in a secluded dell at Tatton Park, in Cheshire.

All over the world people are attracted to Japanese gardens, usually because they provide a tranquil environment, designed to give the impression of a natural landscape at its most serene. They possess a unique aura of calm, which derives from an economical, almost minimal use of materials, whether for building or planting.

A garden in the Japanese style is intended to offer peace and quiet contemplation, with restraint, order, harmony and decorum as the guiding design principles. It is an expression of love for living things, acceptance of the transience of Nature reflected in the changing seasons, and an inspired vision of the eternal.

From the tiniest courtyards to the grandest parks, Japanese gardens invite one to linger and savour their timeless quality.

Japanese-style gardens first became popular in the West in the second half of the nineteenth century. They were part of a craze for all things Japanese that swept Europe and America for about fifty years after the country first became more accessible. Until then, Japan had kept her doors tightly shut against the rest of the world with a brief exception in the seventeenth century, after which only a small group of Chinese and Dutch merchants, confined to a tiny island outside Nagasaki, were allowed to continue trading. The Dutch East India Company sent back to Europe Japanese porcelain and lacquered (japanned) chests and cabinets. What most people knew of Japan were the flowers, birds, pine-trees and islands painted on these household objects.

Rounded mountains, lushly forested, rise up out of a lake, forming a contrast with the austere elegance of Mount Fuji. For centuries, Japanese garden designers have sought to re-create the smooth lines and sinuous curves of the Japanese landscape. A vermilion torii gate marks the entrance to a Shinto shrine.

At first, it was the idea of Chinese rather than Japanese gardens that captured the imagination of Europeans, following the well-established fashion for Chinese motifs on porcelain, furniture and fabrics. When the first western accounts of real Chinese gardens began to appear in the second quarter of the eighteenth century, they sparked a vogue for mock-Chinese garden houses, which began in Britain and quickly spread to France and other countries. Pavilions and pagodas were used instead of classical temples, by then an established feature of English landscape gardens. In the western imagination, Chinese gardens were idyllic pleasure-grounds where languid ladies and gentlemen spent their time amusing themselves, drinking wine and playing musical instruments. When travellers returning from the Far East described real Chinese gardens as lacking the symmetry of European ones of the time (most of Europe was still under the influence of the French formal style), this apparent lack of constraint was welcomed by those eager to throw off the chains of French tradition. The charm of the Chinese style was thought to lie in the variety of scenery contained in one garden. Sir William Chambers (1723–96), the designer of the Chinese Pagoda and other buildings in Kew Gardens, felt that Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown (1715–83), the great eighteenth-century English landscape gardener, was going too far to a ‘natural’ style of open landscape. In his Dissertation on Oriental Gardening (1772), Chambers proposed a greater use of contours, a more informal and varied style of planting shrubs, especially flowering ones, and the use of buildings to add diversity to the landscape. His theories were presented as though they were the tastes of the Chinese.

Angular rocks can be dynamic; these also reflect the shape of the native fir trees that surround this dry garden designed by Terry Welch in Seattle, Washington.

Japanese gardens were also seen through a haze of preconceptions about the luxuriant, sensual East. They were considered to be as highly artificial as Chinese ones, but while Chambers believed that a careful use of artifice enhanced a garden, Japanese gardens were often described as mannered and affected. In other fields of art, Japanese styles did not produce such doubtful reactions. Once Japan began to open her doors, more screens, fans, silks and wood-block prints than ever were exported to the West, with an immediate effect on artists and other people. While painters experimented with unfamiliar Japanese techniques, shops started catering to the taste of the British and French for exotic objets d’art. In 1875, Arthur Lasenby Liberty launched his first shop in London selling Japanese silks. Operas and operettas on Japanese themes soon appeared on the stage in London and Paris, among them Camille Saint-Saëns’ La Princesse jaune (1872) and Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado (1885). Both of these made Japan a land of fantasy, though Gilbert actually visited a Japanese village at an exhibition in Knightsbridge about the time The Mikado went into rehearsal. This village employed craftsmen, dancers, musicians and acrobats brought over from Japan; there was also a tea house and a garden with serving maidens whom Gilbert photographed.

Images of Japan

The theatre had a growing pool of sources to draw on. Many travel books were published between 1870 and 1890, recording the experiences of the first intrepid visitors. Novels soon followed, often romantic tales about Japanese women and western men, set in a decadent, sensual Japan. Pierre Loti’s Madame Chrysanthème (1888), based on his experiences as a naval officer in Nagasaki, was made into an opera by André Messager in 1893, and both forms had some influence on Giacomo Puccini when he came to compose Madame Butterfly (1904). Loti’s central character arrives in Japan expecting to see tiny paper houses surrounded by flowers and green gardens. Though he thinks nothing of this culture, he looks forward to seeing his ideas of Japan realized, but after some time there his prejudices turn into a deep dislike for what he interprets as Japanese artificiality. Loti’s novel helped to spread the image of miniature gardens with misshapen pine-trees, diminutive bridges and minute waterfalls – a landscape inhabited by flitting, child-like women with butterfly sleeves, glimpsed beneath the curving eaves of a tea house.

Another popular western image of Japan was of a land smothered in flowers. At the end of the nineteenth century, one of the greatest hits on the London stage was a musical extravaganza called The Geisha, which opened at Daly’s Theatre in 1896. The curtains opened on a view of the Tea house of Ten Thousand Joys, with geishas posing on a hump-backed red bridge spanning a carp-pond. Flowers were used to establish the ‘Japanese’ setting: in the first act, wisteria dripped from the eaves of the tea house (though wisteria is never grown against a house in Japan); in the second, the stage was overflowing with chrysanthemums, which flower much later (though no time was supposed to have passed between the acts). Japanese gardens were associated with a heady mixture of flowers and nubile young women. In the last act of Madame Butterfly, the heroine and her maid, Suzuki, dance around their house, scattering cherry-blossoms, peach-blossoms, violets, jasmine, roses, lilies, verbena and tuberoses to welcome Butterfly’s American husband, Pinkerton.

A cascade can be glimpsed between drifts of spring colour, here camellias and flowering cherries. The neatly pruned hedge in the front emphasizes the clean, elegant form and the height of the cherry tree.

Keep other trees with long trunks, such as the crape myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica), Stewartia pseudocamellia, and species azaleas such as Rhododendron reticulatum and R. quinquefolium similarly uncluttered with underplanting. They will then provide a valuable focal point in the garden.

Contrasting autumn colours at Batsford Park in Gloucestershire. The umbrella-shaped Prunus hillieri ‘Spire’ (rear right) forms a canopy over the gazebo, while the more informally shaped Acer rubrum helps to blend this group into the woodland background. The vibrantly coloured Acer palmatum ‘Osakazuki’ reflects the shape of the prunus, giving the group its coherence.

Meanwhile, richer gardeners made it fashionable to create Japanese gardens in a corner of their estates. Japanese plants, including maples, sago palms and double-flowered kerria, had been brought to Europe late in the eighteenth century by Carl Pehr Thunberg (1743–1828), a Swedish doctor and naturalist who had travelled to Japan with the Dutch. Many more plants, among them the single-flowered kerria, many azaleas, Japanese rush (Acorus gramineus), the plantain lily (Hosta plantaginea) and the spotted laurel (Aucuba japonica) were introduced to Europe by Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796–1866), a German physician and naturalist who also spent some time at the Dutch East India Company trading station at Nagasaki. Both Thunberg and Siebold wrote books about Japanese plants, and both described their travels in the country. From the time of Japan’s opening to the West until the outbreak of the First World War, many more plant collectors went to Japan, among them Robert Fortune (1813–80), James Gould Veitch (1839–70) and E. H. Wilson (1876–1930) from Britain, Carl Johann Maximowicz (1827–91) from Russia and David Fairchild (1869–1954) from the United States. Fairchild is remembered in particular for his passion for flowering cherries; thanks to his enthusiasm, Japanese cherries were planted along the Potomac River in Washington, DC. In turn, Fairchild sent saplings of American flowering dogwoods to Tokyo, and these trees are still immensely popular in Japan today.

Diplomats coming home were among the first to make Japanese gardens in Britain. A. B. Freeman-Mitford (1837–1916), who became Baron Redesdale in 1902 (and was the grandfather of the writer Nancy Mitford), was one of them. After publishing Tales of Old Japan (1871), he planted fifty species and varieties of hardy bamboo in his garden at Batsford Park, in Gloucestershire. His book The Bamboo Garden (1896) described the collection. At the turn of the century, Louis Greville (1856–1941) built a Japanese-style garden at Heale House, Wiltshire; it included a thatched tea house and a vermilion bridge. By this time Josiah Conder’s books on Japanese gardening had also appeared. An architect commissioned to design western buildings in Japan, Conder (1852–1920) wrote two studies of gardening traditions there: The Flowers of Japan and the Art of Floral Arrangement (1891) and Landscape Gardening in Japan (1893). In these books, especially the latter, readers found more bridges, stone lanterns, rocks and cropped pines to copy.

It had been known for almost a hundred years that the Chinese practised bonsai, the art of growing dwarf trees in shallow pots. An exhibit of bonsai trees was put on show in Liverpool in 1872 in honour of the Japanese Ambassador and his colleagues.

Japanese pines and maples are some of the most popular choices for bonsai as well as being the most important trees used in the Japanese garden.

The idea of garden topiary is essentially the same as that of bonsai, to refine the shape of the tree to bring out its hidden beauty. The maple in this picture belongs to the var. heptalobum group, having the classical seven-lobed leaf form.

The water on the right-hand side of this double cascade falls in sprays, while on the left it is broken into steps.

This hill and pond garden in San Marino, California, follows the Japanese custom of creating a smooth, undulating contour to the land.

In the first two decades of the twentieth century, the fashion for Japanese gardening, both large-scale and in miniature, reached its peak. There was a steady trade in bonsai trees, and gardeners were brought from Japan to build gardens for wealthy patrons as Japanese gardens became the rage among the English Edwardian upper classes. The best surviving examples from the period include Tatton Park in Cheshire; Cottered, near Buntingford, Hertfordshire; and Tully, near Kildare (where another part of the estate is now the home of the Irish National Stud). Mount Ephraim, near Faversham in Kent, has a Japanese rock garden set in a hillside. Coombe Wood, near Kingston, Surrey, is on the site of James Veitch’s own nursery, which sold plants originally collected by Veitch himself, his son James Gould, and E. H. Wilson. The garden here still contains many of Veitch’s plantings, and it has taken in the Japanese-style garden built on the estate next door, which has a particularly beautiful water garden. Iford Manor, near Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire, is the former home of the architect and landscape gardener Harold Peto (1854–1933), who designed the grounds of Heale House. Iford, too, had a Japanese garden, now being restored. Of the various elements of Japanese gardens imitated in Europe, it was probably the use of water that was most easily appreciated. Ponds in naturalistic settings play an important part in the gardens created by painters as different as the Impressionist Claude Monet (1840–1926) and E. A. Hornel (1864–1933), one of the group of artists who were known as ‘The Glasgow Boys’.

Landscape in miniature

The concepts underlying the Japanese art of arranging groups of rocks in the garden have perhaps been less easy to approach for western gardeners, but as an interest in eastern religions has burgeoned in the last thirty years, the esoteric aspect of Japanese gardening, particularly the Zen tradition, has caught the imagination of gardeners elsewhere. A group of rocks in a dry garden can symbolize Buddhist teaching, aid meditation or simply create a feeling of solidity and permanence. Though it might seem odd, there is a recognizable link between these austere, abstract gardens of rocks and sand and landscaped pond gardens, for if there is one thread that runs through the entire tradition of Japanese gardening during the last twelve centuries, it is a love of the diverse landscape of the Japanese islands: hills covered with pine forests and thickets of bamboo, valleys of golden rice fields, the open sea dotted with islands, the surf that rolls up on smooth, glistening sands or batters itself against a rocky coast. There is also an affection for each of the four seasons, which are clearly marked in the temperate marine climate of the country: the snows and frost of winter, the cheerful sunshine of spring, the sheen of water on leaves during the rainy month, the relentless glare of summer, the clear blue skies of autumn.

These are the elements constantly brought into the Japanese garden. From earliest times, formal gardens represented the mountains, woodlands and waterfalls, lakes, streams and open grassland of the natural world. In contrast to the image of a bower of flowers, Japanese gardens of all styles weave their rich tapestry in shades of green, emphasized by white gravel and the greenish-grey of rocks. Flowering trees, shrubs, perennials and annuals are used with great restraint, as are plants with berries or variegated leaves. Even the use of deciduous trees, including the fabulous Japanese maples that come in such a range of brilliant leaf colours, is generally restricted. Seasonal interest is concentrated on a small number of carefully selected and positioned plants of this kind. In practical terms, this means that Japanese gardens do not have an off-season during winter, since the rocks, the sand, the trained evergreens and conifers do not change. Winter brings no dug-up borders of bare earth, simply because in these traditional gardens there are no borders or beds in the western sense.

This is not to say that the Japanese are not passionate hybridizers of plants, mesmerized like people all over the world by the endless patterns and colours Nature seems capable of throwing up in the game of genetic roulette: countless prize cultivars of tree peonies, morning glories, chrysanthemums and, more recently, calanthes have been coddled and cherished by enthusiasts. In the eighteenth century there was a craze for variegated camellias and mandarin oranges (Citrus tachibana) not unlike the tulipomania that overtook Europe in the previous century. Chrysanthemums were exhibited with just as much competitive pride as auriculas and pinks were in the north of England. These passions, however, are kept separate from the traditional art of garden-making. Fancy cultivars of Iris ensata, for example, are more often grown in pots than planted out in the garden, so the large, showy blooms can easily be admired much closer at hand.

Perhaps the best way of capturing the spirit of Japanese gardens is not to attempt to grow rhododendrons and maples where they simply will not thrive, or to build vermilion bridges and tea houses – not even necessarily to create waterfalls gushing over rocks – but to try to re-create a local landscape the gardener loves. It may be done with heathers in Scotland, for example. The important thing is to draw on the means of arriving at the special stillness and serenity which Japanese gardens exude, and use them like any other garden tool, instead of trying to reproduce faithful copies of a foreign land. The aim is to achieve an effect of controlled calm by emphasizing space, austere simplicity and shapes.

This Swiss garden seems to extend to the horizon, bounded only by the sky and the grey silhouettes of distant mountains. The Max Koch Garden succeeds in merging flawlessly together an intimate water garden planted with Iris laevigata and a panoramic view over the lake. The raised decking provides an ideal viewing platform, and the choice of natural materials for both the decking and the bridge prevents them from clashing with the overall feel of the garden.

Changing gardening styles

Most of the terrain of Japan has acid soil, which largely determines the choice of garden plants there. Most are native species; others, such as the tree peony, flowering peaches and flowering crabapples, were highly prized Chinese shrubs brought to Japan in ancient times; still other shrubs, like Mahonia japonica, were Chinese medicinal plants imported into Japan in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A handful of European and American plants have become firm favourites in Japan, especially broom and the American dogwoods. The Japanese describe their gardens as naturalistic, but they are not woodland or wild-flower gardens. Instead, a careful selection of plants, rocks and stones encapsulates and embodies the spirit of the local landscape.

As more and more exotic plants arrive from overseas, garden styles are changing in Japan too. The fashion these days is for English-style gardens with lavender and old-fashioned roses, even though both tend to suffer in Japan’s more humid climate. Fewer and fewer houses are being built in the traditional way with wood and wattle and daub; modern houses are made of prefabricated materials instead. Inside they have carpets, not thick straw mats; curtains, not sliding doors covered with rice-paper. For more than 1200 years, people in Japan sat on cushions on the floor; they gazed at their gardens from immaculately polished verandahs. Fifty years ago habits started to be westernized. Just as the furniture in the living-room is more likely these days to be sofas and coffee-tables, people are likely to look out on their gardens from a glass window or a patio door. Styles in both architecture and design change and develop. Gardens in Japan now tend to be brighter, with fewer sombre evergreens and more lawn. There are more flowers too. But sometimes the old ways can remind us of a different way of thinking about gardens. For those unfamiliar with the techniques and concepts traditional to Japanese gardening, learning about these traditions may stimulate new approaches and help them to realize their own visions in the gardens.

The tradition of Japanese gardening stretches back 1400 years. Though different styles developed as the social functions of gardens changed, the underlying concept has stayed surprisingly consistent. The approach has always involved paring the natural world down to its essential elements to refine an understanding of the workings of both Nature and time. Gardens are often passed on from generation to generation like prized bonsai trees. They transcend time and fashion. Their shapes and forms take on a universal appeal which brings peace to those who inherit this art of gardening.

The four basic types of Japanese gardens are described in the next chapter: hill and pond gardens, dry gardens, tea gardens and courtyard gardens.

An unpainted, ornamental bridge is well suited to a woodland setting. At the same time, well-groomed evergreen shrubs and azaleas provide the touch of formality a bridge of this type requires. Middle-sized pines, enkianthuses, and taller evergreen shrubs can be arranged together with ground-hugging junipers next to water. Conifers such as Taxus cuspidata and Juniperus chinensis have many dwarf forms that can be used in these situations. Prune the trees and shrubs carefully to keep their overall shape.

The earliest descriptions of gardens in Japan are found in seventh-century poems. From them it is possible to see that lakes and islands and bridges were already the principal features of the aristocratic gardens of that period. Picturesque rocky shorelines were also being created to add variety to the landscape.

Right from the beginning, Japanese gardens were the products of a highly self-conscious culture that tried to recreate naturalistic landscapes near people’s houses, but also to find pleasure in reminders of Nature’s rugged and untamed wilderness.

THE HILL AND POND GARDEN

The choice of landscapes to reproduce was closely connected with how people saw their country. By building islands in the middle of lakes they were confirming their identity as an island people. Gardens of this kind came to play an even greater role in aristocratic life once the imperial court was moved to Kyoto at the end of the eighth century. As this area was blessed with many springs, as well as being watered by several clear rivers issuing from the richly forested mountain ranges surrounding the city to the north, east and west of the broad valley floor, it is hardly surprising that lakes became more significant in gardens than ever before. About the time the first imperial palace in Kyoto was being constructed, a garden was built around a sacred spring just south of the palace grounds. This garden eventually included a large lake with a sacred island, overlooked by another palace. Later aristocratic gardens in Kyoto were modelled on this imperial prototype.

A vermilion gateway forms a brilliant contrast to the deep blue Californian sky. Sequoias are combined with traditionally pruned pines in this San Francisco garden. The short trees and shrubs planted down the incline are neatly pruned, helping to create an impression of dense planting. A low embankment in a more informal garden can be planted with a single variety of a weeping bush such as Japanese bush clover (species of Lespedeza) which produces tiny purple-pink, pea-like blossoms in autumn.

For the next four centuries, a highly sophisticated culture flourished in these garden palaces. This society gave birth, for example, to The Tale of Genji, a portrait of the life of refined and sensitive emotions led by the nobility. The author, Lady Murasaki Shikibu, lived at the end of the tenth century and the beginning of the eleventh. The exquisite feelings she described include responses to the natural world, though these reactions are kept within the conventions of the time. The court revolved around a strict calendar of elaborate rituals and splendid ceremonies, and it made great formal occasions of excursions to outlying hills in the autumn. There the nobility amused themselves by picking wild flowers which they then replanted in their gardens at home. Pilgrimages to more distant temples also provided rare opportunities for these aristocrats to leave the confines of the city. Along the way they were able to catch glimpses of white beaches, wind-tossed pines and the sea itself. These were the landscapes they wanted to have re-created for them in paintings and in their gardens.

A weeping willow is carefully positioned over a pond so that it casts its reflection in the water. Japanese maples are also often used in this way.

A typical palace faced south and looked out on an open expanse of sand, a ritual space, beyond which might be some scattered planting, and then a large lake fed by a channel which was dug so that it ran into the garden from one corner of the estate, passing under several corridors of the palace on its way. This stream was embellished with rocks to simulate a rippling brook, and around it the terrain was made to undulate gently. Here, the clumps of wild flowers gathered in the hills were replanted: balloon flowers, hostas, yellow valerian and bush clover. The nobility of Kyoto loved gentle, sloping mountains like the ones nearby. There were also older memories of the perfectly shaped, dome-like mountains around the older capitals of Nara and Asuka – mountains immortalized in some of the oldest poetry in Japan. These ‘feminine’ mountains are quite unlike the precipitous, craggy, dangerous mountains lying further to the east. After the opening of Japan to the West in the nineteenth century, these were called the Japan Alps.

These standing stones surrounded by a birch forest carpeted with soft moss look ancient. Japanese gardens strive to attain this timeless quality but it does take patience to achieve it. There is certainly quiet enjoyment to be savoured in planning how a garden will look to future generations.

The white, sparkling beaches that once surrounded the Bay of Osaka were copied in these grand gardens. For the sake of contrast, rocky shorelines were often built to represent Nature’s wilder aspects. The lake would have up to three islands, all connected with bridges. During courtly entertainments, these islands provided an ideal stage for musicians, who also performed from gilded and painted boats. Guests would admire them from the palace verandah as they caught sight of them between the pine-trees. They would listen as the music wafted closer, then became more distant as the boats floated away. Another room from which the garden could be seen was an open one built directly over the lake and connected to the rest of the house by a long corridor. From here, or from a separate pier, elegant princes and their ladies were able to go out on the cool lake on fierce summer days.

Temple and palace gardens

Sadly, none of these palace gardens has survived the centuries in anything like their original shape, but there are other lake gardens in the grounds of Buddhist temples. As they were intended to evoke an idea of the paradise Buddha was thought to inhabit, they are referred to as paradise gardens. In these gardens, the main hall of the temple is built facing the lake. From this hall, the statue of Buddha gazes serenely over his tranquil domain where the sacred lotus flowers bloom.

In the twelfth century, political power began to shift to the warrior classes. Architectural fashions began to evolve too, reflecting the provincial, even rural background of many of the new warlords. Some of the most powerful of them became Buddhist monks in later life, and this meant that features taken from monastic buildings were also used in many of the villas and retreats they commissioned. Many gardens lost the open ritual space of swept sand that formerly divided the house from the lake. Rocks gradually began to be more prominent in the landscape. Lonely outcrops of stone appeared in the middle of garden lakes, and they were increasingly identified with sacred mountains in Buddhist and Chinese mythology. Paths were planned to allow these gardens to be seen from different directions, and the stroll garden came into being.

Water, buildings, rocks, moss, trees, shrubs: all had their part to play in creating the complex effect of these gardens. With the development of the tea garden in the sixteenth and seventeeth centuries, new influences were swiftly absorbed into the design of stroll gardens, and what was intimate and modest in the tea garden became grand and ambitious. It was around that time that the famous imperial gardens belonging to the Katsura and Shugakuin Palaces near Kyoto were built. At Katsura, stepping stones, paths and bridges meander among five large and small islands. In one place, a pebbly spit of land juts out into the lake, its point adorned with a single round stone lantern standing on an outcrop of rock like a miniature lighthouse. This headland was thought to represent a celebrated landscape on the coast of the Sea of Japan, known as the Bridge to Heaven. The route around the garden at Katsura dips into shady glens and