Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

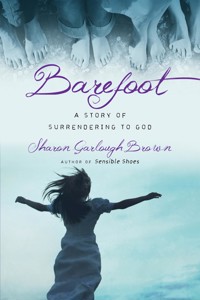

- Herausgeber: IVP Formatio

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Serie: Sensible Shoes Series

- Sprache: Englisch

Logos Bookstore Association Award Foreword INDIES Book of the Year Awards Finalist The spiritual journey takes unexpected turns for the women of Sensible Shoes in this third book of the series, continuing on from the events of Two Steps Forward. Having been challenged to persevere in hope, can they now embrace the joy of complete surrender? Mara: With two boys at home and a divorce on the way, can she let go of her resentment and bitterness and find a rhythm of grace in her "new normal"? Hannah: With Nathan by her side, can she let go of expectations—and even her reputation—as she charts a new course? Charissa: As her approaching due date threatens to collide with new professional opportunities, can she let go of her need for control and embrace the unknown future with trust? Meg: With disappointment over broken relationships and unfulfilled dreams, can she let go of her fear and worry in the face of even greater challenges that lie ahead? Join the women of the Sensible Shoes Club in a poignant story that reveals the joy that comes from laying our lives at the feet of God and standing barefoot on holy ground.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 546

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.

Exodus 3:5

For Jack, my dearest companion. Together we have glimpsed the glory of God.I love you.

To be a pilgrim means to be on the move, slowly to notice your luggage becoming lighter to be seeking for treasures that do not rust to be comfortable with your heart’s questions to be moving toward the holy ground of home with empty hands and bare feet.

From “Tourist or Pilgrim” Macrina Wiederkehr

Contents

Part One

The Pilgrim Way

Meditation on Psalm 131 – A Prayer of Rest

Part Two

Crossroads and Thresholds

Meditation on Romans 8:31-39 – Confidence in the Love of God

Part Three

Holy Ground

Meditation on John 13:1-15, 21 – Loving to the End

Acknowledgments

Companion Guide for Prayer and Conversation

Praise for Barefoot

About the Author

The Sensible Shoes Series

Formatio

More Titles from InterVarsity Press

Copyright

Part One

The Pilgrim Way

Blessed are those whose strength is in you, whose hearts are set on pilgrimage.

Psalm 84:5

one

Meg

Resilient. That was the word Meg Crane had been searching for. Resilient. “You’re not resilient,” Mother had often said, her accusing tone ringing in Meg’s ears, even almost a year after her death. “You’ve got to learn how to bounce back. Move on.”

Meg rolled over in her twin-size bed, the same bed she had slept in as a little girl. Never, in her forty-six years, had she been one to recover quickly from trauma or sorrow, never one to adjust easily to change or disappointment. She knew people able to withstand pressure with remarkable equanimity, to stretch, bend, and adapt to suffering with grace, with hope. She had never been one of them.

Perhaps “resilient” would be a good word to embrace for the new year. Resilient in hope. Especially in light of everything that had been thrown upside down, just in the last month.

She propped herself up on her elbow, the old box springs creaking beneath her spare, five-foot-two frame, and gazed out her second-story window at the gray gloom. The gnarled wild cherry tree in the next-door neighbors’ backyard, visible from Meg’s window ever since she could remember, offered a picture of resilient hope. Years ago, when Mr. and Mrs. Anderson lived there, violent winds tore through West Michigan on a balmy summer night and nearly ripped the tree out, leaving the roots exposed. The next day neighbors gathered around it, some of them bracing the trunk upright with hands and shoulders while others stamped the roots back into the soil again. Mother chided them from an upstairs window: they were fools, making such a fuss over a tree. But Meg secretly cheered them on. The tree always leaned after that storm, but it lived, its lopsidedness testifying to resilience, its yearly blossoms to hope.

Resilient in suffering, not impervious to it. That was the silent witness of the stooped tree: not denial of the storm but perseverance, character, and hope as a result of it.

Oh, for that kind of testimony.

The faucet sputtered in the bathroom down the hall, the plumbing pipes clanging in arthritic protest. Hannah was awake. Strange, how quickly Meg had grown accustomed to having someone else in the house again. A ceramic floral mug on the kitchen counter, a towel draped over the rusting shower door, a second toothbrush beside the chipped enamel sink—all were cheerful reminders that Meg was not alone. Even if Hannah’s presence in the house was temporary and sporadic, Meg was grateful for her company.

In the months since meeting one another at the New Hope Retreat Center, Hannah had become like a sister. And not just Hannah, but Mara and Charissa too. The Sensible Shoes Club, Mara had dubbed them. Meg, who had spent most of December in England visiting her daughter, was looking forward to walking together in community again. She needed trustworthy spiritual companions on the journey toward knowing God—and herself—more intimately. She needed a safe place where she could be honest about her struggles to perceive the presence of God in the midst of her fear, disappointment, and sorrow.

But once Hannah finished her nine-month sabbatical, their newfound, intimate community would inevitably change. And then what?

Don’t you think she could just stay here? Mara had asked Meg while they served a meal together on Christmas Day at the Crossroads House shelter. She doesn’t have to go back to Chicago, does she? Couldn’t she just tell her boss that she’s been reunited with the love of her life and she’s gonna stay in Kingsbury?

Meg didn’t know how sabbaticals were supposed to work, whether there were rules about not leaving the church after taking a break. You know Hannah, Meg had replied, how devoted she is to ministry. I can’t see her taking a gift from them and then not going back there to serve.

As if on cue, Hannah appeared in the doorway in her white terry cloth robe and slippers, her light brown, gently graying hair still rumpled from sleep. “How are you feeling?” she asked.

Meg boosted herself up against the headboard. “Sorry—did my coughing keep you awake?”

“No, I only heard you this morning, after I was up.”

“Airplane germs,” Meg said, sniffling. “I hope I don’t spread them to you.”

“I’ve got a pastor’s immune system,” Hannah quipped. “Years of hospital visits.” She swiveled Meg’s desk chair toward the bed and sat down. “Any word from Becca?”

“No. I need to learn how to text. Guess she’ll call when she feels like it.” Hopefully, Becca would make it safely back to London after celebrating her twenty-first birthday in Paris with her forty-two-year-old boyfriend, Simon.

The very thought of his name conjured the vile experience of meeting him. There he stood at the base of the London Eye, dressed in a tweed overcoat and a pretentious hat, his middle-aged hands roving across Becca’s body, his theatrical voice dripping with condescension, his lips curled into a gloating sneer. Maybe he would tire of her and find some other young innocent he could manipulate and control. You still don’t get it, do you? Becca would argue. I’m not a victim! And I’m not a little girl anymore. I’m happy. Happier than I’ve ever been in my entire life. Accept it, okay?

No. Meg would not accept it. And she knew what her mother would say. As impervious as her mother had been to sorrow, she had never been impervious to shame or unruffled by the appearance of impropriety. Why in the world would you let her be involved with him? Mother would demand. Why did you even agree to her going to Paris? You should have stayed in London and taken control.

“You okay?” Hannah asked.

Meg shrugged. “Just having imaginary conversations with people who aren’t here.”

“Becca?”

“And my mother. She would have had a conniption over the whole Simon thing.” Meg tugged at the hem of the blanket. “Tell me the truth, Hannah, what you really think. Should I have stayed in London? Fought to keep Becca from going to Paris?”

Meg had never posed the question, and Hannah had never offered an unsolicited opinion. “I’m not sure that would have accomplished anything,” Hannah said after a few moments, “except make her more determined. More angry. And you were asking God to guide you in love, to show you what loving Becca looked like. I think it was courageous to love her by letting go, by not trying to control her. Hard as it is.”

Yes. Very hard. Very hard to trust that the story wasn’t over, that God placed commas of hope where Meg might punctuate with exclamation points of despair. “I have dreams. Nightmares. I see Becca in danger—sometimes she’s standing right on the edge of a cliff—and I try to scream to warn her, but nothing comes out of my mouth, and I try to run toward her, but my legs won’t move. I’m totally helpless. And it’s terrifying.” She clutched her knees to her chest. “Sometimes I feel like my own prayers just hit the ceiling and bounce off. Keep praying for her, okay?”

“I will. And for you too, Meg.”

“Thanks.” Meg pulled another tissue from the box on her bedside table. “Much as I hate to, I think I’d better pass on serving with you guys at Crossroads today. I’m worried I’ll be coughing all over the soup.”

“Mara will understand,” Hannah said. “We’ll have plenty of chances to be there together. You need to get your rest.”

Meg nodded. Maybe an entire day in bed was a necessity, not a luxury.

“I’ll put the kettle on,” Hannah said, “and bring you a cup of tea with honey.” Before Meg could protest and insist on getting her own, Hannah was out the door, her footsteps padding down the hardwood spiral staircase, her warm alto voice singing a melody Meg did not recognize.

She reached for the daily Scripture calendar Charissa had given her (“Just a small thank-you,” Charissa had said, “for letting us know your old house was for sale”) and flipped the page to New Year’s Eve. In five short weeks Charissa and John would take possession of the house Meg and Jim had once shared, the home where they had dreamed their dreams about having a family and growing old together. Now, twenty-one years later, Charissa and John would dream their dreams in that same space and, God willing, they would bring their baby home together in July to the room Jim had once lovingly prepared for Becca. But Jim had not lived to bring Becca home. He had not lived to meet and hold his daughter. He had not lived.

For God alone my soul waits in silence, Meg read from the calendar, for my hope is from him.

Hope. Again and again, that word appeared, as if the Lord himself were whispering it in her ear. Hope, not in a particular outcome, but in God’s goodness and faithfulness, no matter what. Hope, not in an answer or solution, but in a Person. Hope, in him, through him, from him.

“Look,” Meg said when Hannah returned with a tea tray.

Hannah placed the tray on Meg’s bed and took the calendar to read. “There’s your word again.”

“It’s like I’m living in an echo chamber.”

Hannah grinned. “I know the feeling.” She passed the calendar back to Meg and hooked the leg of the desk chair with her foot, pulling it closer to the bed. “Thank God he doesn’t assume we’ll hear him the first time.”

Meg took a sip of tea, the taste of honey lingering on her tongue. Yes, thank God.

She knew her honest version of that verse most days: For God alone my soul doesn’t wait in silence, for my hope is not from him. Instead of waiting for God in hope and peace, she waited with agitation, restlessness, and anxiety. Even with everything she had seen about God’s faithfulness, even with everything she’d experienced the past few months about God’s presence and love, she still found it hard to trust. So that’s what she was learning to offer—the truth. To God. To others. To herself. No denying her fears. No stuffing her sorrow. All the anxiety and the heartache, the regret and the guilt, the longings and the desires, the wrestling and the sin, the past and present and future—all of it belonged at the feet of Jesus. All of it.

Meg tried to offer a breath prayer but was seized with a fit of coughing as she inhaled.

“You sound awful,” Hannah said. “How about if I bring you something for that cough?”

It had been a while since Meg had been sick, even with a stuffy nose. “I don’t think I have anything,” she said.

“No problem. I’ll take a quick shower and go get some medicine for you.”

“You don’t have to do that—”

But Hannah was already on her feet. “I know I don’t have to. I want to.” She took a pad of paper and a pen from Meg’s desk. “Here—make a list of anything else you need, okay?”

“Hannah, I—”

“No arguing.” Hannah pointed her finger, her tone playfully firm. “You’re one of the ones telling me I need to practice resting and receiving. You can practice with me.”

Meg gave a mock salute.

“And put a couple of things on that list that are just for fun,” Hannah said. “You can practice playing too.”

“I was never allowed to play when I was sick. It was against the rules.”

Hannah’s eyes filled with a deep kind of knowing. “All the more reason to do it now.”

Meg leaned her head back against her pillow and stared up at the ceiling, remembering lonely, censured sick days when her childhood room was converted into a confinement cell, with freedom granted only for trips to the bathroom or to the kitchen to forage for food. How many hours had she lain in bed, tracing the floral wallpaper pattern with her finger and making up stories in her head because even pleasure reading was forbidden?

There was more—always more—to offer at the feet of Jesus, if she had courage enough to see.

Mara

The muffled yapping followed by a plaintive whine was Mara Garrison’s first clue that the cardboard box and silver duffel bag thirteen-year-old Brian was carrying contained something other than a few days’ worth of dirty laundry.

“Hey!” she called to her youngest son, who had not removed his slush-covered boots or headphones when he entered the house. “Brian!” Mara thrust out her sudsy dishwater hand from the sink and caught his sleeve as he passed by. He flicked his wrist and swept through the kitchen without looking at her, his chest puffed out in a swagger that perfectly mimicked his father’s. “Hey!” She wiped her damp hand on her jeans and charged after him, reaching the door to the family room seconds before he did and blocking his path with her plus-sized body. She extended her elbows to touch the doorframe so he couldn’t get past her, then motioned for him to take off the headphones. Brian pulled one a few inches away from his ear.

“How about a ‘Nice to see you, Mom!’”

If looks could kill, he’d be charged with murder.

“What’s in the box?” she asked, pointing with her chin.

He hooked the headphones around his neck. “Nothing.”

“Nothing” yelped.

“Dad got him a dog,” Kevin replied, closing the garage door behind him with a hard slam before stooping to remove his boots.

Brian spun around and glared at his older brother.

“Don’t be such an idiot,” Kevin said. “It’s not like you could keep it a secret.”

“Open the box,” Mara commanded, her voice surprisingly calm.

Brian tried to scoot around her.

She braced herself against the door frame. “I said open the box.”

He narrowed his eyes at her, the corner of his mouth twitching, the vein near his freckled temple pulsating. Just like his father.

“Open the frickin’ box!” Kevin exclaimed. He snatched it away from his brother and set it down on the brown tile floor before opening the flaps. A wide-eyed, tan fur ball blinked at Mara.

Tom, her soon-to-be-ex-husband, crowed in her head. Happy New Year!

Kevin scooped up the quivering dog from the soiled newspapers and cradled it. The floppy-eared, shaggy-coated mutt licked his finger and whimpered. Brian wrested the dog away. “Bailey’s mine,” he growled, pushing Kevin’s chest with the palm of his hand.

Kevin punched Brian’s shoulder. “Then don’t suffocate him.”

In reply, Brian shoved Kevin hard.

“Hey!” Mara shouted. “Knock it off! Both of you.” Though she’d expected Tom to pull some stunt with the boys over Christmas vacation, she hadn’t predicted this particular maneuver.

For years she had put her foot down, insisting the boys could not have a dog because she knew who would end up taking care of it, and she didn’t want the additional responsibility. Tom traveled out of town most weeks, the boys participated in multiple extracurricular activities, and Mara barely managed the pace of solo parenting.

Now that Tom had filed for divorce and moved out to pursue a new promotion and new life in Cleveland—now, when Mara needed to look for a job and wasn’t even sure she would be able to afford to keep the house once the divorce was final in June—now Tom had given exactly what Brian wanted. It was a skillful ploy for maintaining loyalties and creating even more hostility if Mara took the dog away. She could imagine Tom’s mirth when he backed out of the driveway after dropping the boys off. He would probably smirk all the way through Michigan to Ohio.

While Brian disappeared with the dog and his bag, Kevin lingered by the kitchen counter to inspect the apple pie cooling on the stove.

“Want to fill me in?” Mara asked, hands on her hips. Ever since Kevin first confided in her about Tom’s job promotion a few weeks ago—news which Tom had decided not to share with her—he had become a fairly reliable informant. He broke off a tiny edge of golden crust to taste.

The dog, Kevin explained, had been purchased through Craigslist after Brian threw a fuss about wanting—needing—one. “I told Dad you wouldn’t be happy about it.”

Exactly.

Muttering a few choice words under her breath, she reached for her phone and then stopped midnumber.

No. This was precisely what Tom wanted. In fact, he was probably waiting for his phone to ring, counting on it ringing.

Let him wait and wonder.

She would figure out how to exact her revenge. She would find some weakness and exploit it, or she’d use the dog as leverage for keeping the house. Tom wanted to play games? Fine. She’d play. Brian wouldn’t be able to have a dog if she and the boys were forced to move into some rental property, and she could readily sow those seeds of blame and resentment. Don’t get too attached to it, she’d say, because once the divorce is final, we’re probably gonna have to move into a really small house with no pets allowed—all because your father’s too selfish to let us stay here.

But for now, Mara would play it cool, in case Kevin was acting as a double agent. “Did your father already buy a crate and everything?”

“Nope. Just food and a leash.”

“Well, we’ll have to go shopping, then.” Mara had recently found a credit card in Tom’s name that she hadn’t used in a few months, tucked inside an old wallet. The dog would need lots of things. Lots of expensive things. The most expensive crate she could find, for instance. And toys. And a plush monogrammed bed. Maybe it would also need obedience training. Tom would quickly discover how costly his gift was—even without vet bills—and if he complained about it, they would need to give up the dog. I’m sorry, Brian, Mara would say, but we can’t afford to keep him. Talk to your father about that.

“And what about you, Kev?” she asked, injecting cheerfulness into her voice. “What did your father give you?” Tom wouldn’t give Brian an extra Christmas gift without keeping the boys even.

“Some surfing stuff.”

Predictable. Tom had probably planned some expensive summer vacation for himself and the boys. Hawaii, maybe. But she wouldn’t think about that now. For now, she had two things that needed her immediate attention: finish baking for their family dinner and get to Crossroads by ten thirty with Kevin.

She was proud of him. Very proud of him. Though Coach Conrad had given him ten mandatory hours of volunteer service when he picked a fight with a teammate after a December basketball game, today Kevin would serve hours eleven, twelve, and thirteen at his own suggestion. “’Cause I won’t get to see the kids as much after school starts again,” he’d told her. “And I bet some of them will be leaving soon, don’t you think?”

Kevin had surprised Mara by how quickly he’d taken to playing with them. At fifteen, he had never spent much time around young children. He was a toddler in diapers when Brian was born, and Mara, aware of his jealousy of the new baby, had been hypervigilant about supervising him. But at Crossroads she’d watched him with delight from the corner of her eye as he read books to preschoolers who clambered on him like he was a jungle gym, their limbs fastened around his freckled neck and sinewy shoulders, clinging to him like Velcro. She’d seen the flash of his colored metal braces (currently Packers’ green and gold) when his mouth stretched into an uncharacteristic broad grin. Even though he’d tell them in a firm big-brother voice, Now sit down and listen to the story, he didn’t try to disentangle himself from their happy chaos. For some of these homeless kids, Kevin was one of the few male figures they had access to, and they slurped up his attention with thirsty, frenzied gulps. Jeremy, her oldest son, had been one of those clamoring preschoolers twenty-seven years ago.

She checked the clock on the microwave. She still had enough time to set the dining room table with her best china, whip up a batch of her famous snickerdoodles, and slice some raw vegetables for an appetizer. Crudités, the neighborhood women called them—the same women who boasted about growing their own herbs in their gardens to make their dips, dressings, and sauces. If Mara used anything other than Hidden Valley Ranch dressing or Skippy creamy peanut butter for veggie dips, the boys would mutiny.

Once the cookies were in the oven, Mara ironed her green-checked tablecloth and napkins. Years ago, after her mother died, Mara inherited her grandmother’s china, one of the few treasures Mara retained from her childhood. Mara remembered a few family gatherings—all the more special because they were so rare—when her grandmother pushed two rickety card tables together at her apartment, covered them with linens, and set them with her floral English bone china and crystal stemware. Though Mara’s older cousins had the privilege of lighting the candles, Nana let Mara fold the napkins and arrange the silver, two forks to the left of each plate. Mara also got to arrive early to help her cook. None of the other cousins were granted such intimate access to Nana’s culinary secrets.

Mara could still see her in her polka-dot apron, stoop-shouldered at the stove, adding brown sugar and ginger to the melting butter. Nana supervised the yams until they reached just the right consistency for Mara to mash. Then they would spread the creamy mixture into the casserole dish and sprinkle marshmallows on top. Nana always let her eat three marshmallows from the bag.

Another tradition Mara could pass along to her granddaughter, Madeleine, someday.

She smoothed the tablecloth, picturing her own family gathering in a few hours. Though Brian would be his usual surly self, at least Tom would not preside at the head of the table, criticizing the meal, provoking Jeremy with barbed insults, or targeting her daughter-in-law, Abby, with sexist and racist jokes.

Happy New Year!

Mara opened her china cabinet and removed her grandmother’s dinner plates from the top shelf, humming as she counted out five, not six. Just as she was pivoting toward the table, her foot caught on something, and she stumbled forward. Before she could regain her balance, two plates catapulted out of her hands and landed with a devastating crash on the tile floor.

What the—

Cowering beneath a dining room chair was Brian’s dog.

“Brian!” she shouted, shaking with anger.

She had been so absorbed in meal preparations, she had forgotten about the new four-legged squatter. She glared first at the animal, then at her grandmother’s plates in pieces. “Brian!” She yelled so sharply that the dog fled behind the sofa. Kevin came to the top of the basement stairs, took one look at his mother, another at the mess on the floor, and shouted down the stairwell to his brother. Brian eventually appeared.

“What?” he demanded, arms crossed against his chest. At the sound of Brian’s voice, Bailey crept out from hiding.

“Get. Your. Dog. Now.” Before Brian could grab him by the scruff of the neck, the dog lifted his leg and peed on an armchair. “Now!”

Brian lunged forward, the mutt evading his grasping hands with bounding, barking circles and zigzags through the family room and kitchen. Too angry to speak, Mara lowered herself into a chair at the partially set table and buried her face in her hands.

Hannah

Hannah Shepley stowed away her phone and, with a deep breath, returned her attention to the checkout counter, where a white-haired employee, his dark wide-rim glasses askew, was trying to figure out how to ring up mascara the customer insisted was on sale. “It says so, right above the display,” the woman said, her multiringed hand perched on her hip. “Buy two, get one free. Count them.” She pointed a well-manicured, emphatic finger at each package on the counter. “Ooooone, twoooo, threeee.”

In reply, the man retrieved a sales circular from beside the cash register, flattened it slowly, and scanned the pictures for a match, his shoulders hunched forward, his left hand atop his head, scratching in thought.

“Oh, for cryin’ out loud,” the woman snapped, snatching the paper away from him. “Here! See? Right here. Here’s the picture, here’s the offer. Maybelline mascara, buy two, get one free. What’s so hard about that?” She spun away from him to grant a commiserating grimace to the customers waiting in line behind her.

Satisfied that the details on the flyer matched the products in front of him, the clerk typed the code into the register and completed the transaction, offering a “Have a nice day” as the woman yanked the receipt from his hand, shoved it into her plastic bag, and stormed out the automatic sliding doors in a rush of cold air.

None of the next three transactions proved any more straightforward, and as his microphone pleas for backup went unheeded, the customers became increasingly hostile. By the time Hannah reached the counter, his brow was beaded in sweat. “Did you find everything you need?” he asked, a weary sigh in his voice.

“All set,” Hannah replied with a smile she hoped communicated she was unruffled by the delay and unlikely to lose patience with him. Thankfully, nothing in her shopping basket was listed in the weekly ad flyer.

A young sales associate, her lips and eyebrows pierced with multiple rings and studs, sauntered by and opened another register. Muttering their relief, the customers behind Hannah leapt to the other line.

Meanwhile, the elderly clerk scanned each item from Hannah’s cart with a slow, almost reverent touch. “My granddaughter loves to color and draw,” he said, holding up the packs of colored pencils, pens, and crayons Hannah had found on the Christmas clearance shelves. Later, when she had more time, she would stop by the hobby store and buy more sophisticated art supplies for Meg, who had mentioned how much she enjoyed sketching at her neighbor’s house when she was a little girl. But it had been years, Meg said, since she had done anything artistic. All the more reason to do it again, Hannah had replied, hearing the invitation to herself in those words.

He was still scanning items. Cough suppressant and decongestant. Honey lemon throat lozenges. Vitamin C tablets. Tissues. A book of sudoku and crossword puzzles. And Yahtzee, because Hannah hadn’t played it in years, and she could still hear the rattle of the dice as her father vigorously shook the cup, calling, “C’mon, sixes!” Maybe Nathan would play with them.

The clerk examined the Yahtzee box, trying to find the barcode. “I think it’s on that side there,” Hannah said.

He spun the box several times, his fingers fumbling. “I’m sorry,” he said.

“No problem. You’re doing fine.” All three customers in the other lane had already left, and Hannah fought the temptation to tap her fingers on the counter. Hadn’t she just chastised Nathan a few weeks ago for his impatience while waiting in line? She had reminded him that he could practice the spiritual discipline of being attentive to the people around him, praying for them while he waited. If Nate were with her, he’d be elbowing her right about now. Her words always had a way of coming back to bite her.

She offered a silent prayer, both for her irritation and for the clerk. Maybe he was new on the job. Or maybe he had been working at this store for decades and was developing senility. Maybe—

“My granddaughter’s real sick,” he said, looking her straight in the eye. “Leukemia.”

—he was distracted by other, more pressing concerns.

“I’m so sorry,” Hannah said, her impatience evaporating.

“We thought she’d be able to be home with us for Christmas but—” His voice cracked, and he returned his attention to scanning and bagging. Hannah watched him pack up the items, then swiped her credit card. “Receipt with you or in the bag?” he asked.

“I’ll take it,” Hannah said, reaching for the bags. “What’s your granddaughter’s name?”

“Ginny.”

Hannah withdrew the crayons, colored pencils, pens, and Yahtzee box from one of the bags and handed them back to him. “Please take these to Ginny.”

“Oh—I can’t—”

“Please,” Hannah said. “Just a little something.” Such a very little something. But from the look of astonishment and gratitude on the cashier’s face, you’d think he had been given a kingdom.

Everyone has a story, her father often said. Everyone. You just need to know how to ask the right questions.

Her father, a retired salesman, had always known how to ask the right questions to establish rapport with potential customers. He had elevated small talk to an art and had a knack for making people feel valued, all of which translated into impressive sales numbers. He was the proverbial ice salesman to Eskimos. But when it came to disclosing his own story, he was Fort Knox.

Like father, like daughter, Hannah thought as she drove back to Meg’s house. And now that her own vault had been unlocked, it was time to explore whether or not her dad was willing to open up.

She had promised her parents before Christmas that she would fly to Oregon to see them in January or February. She hoped to have an honest, face-to-face conversation with them about the family secrets that had turned septic within her because of years of trying to conceal them. After disclosing the truth to Meg and then to Nathan, Hannah was beginning to feel ready to voice the truth to her parents, to tell them about how she had felt responsible for her mother’s nervous breakdown and hospitalization when Hannah was fifteen, about how she had tried to obey her father’s command not to confide in others about their family’s pain. Determined not to betray his trust, Hannah had stuffed the shame and the fear and, without realizing it, had become an internal bleeder. But with radical and precise surgery, the Great Physician had begun the deep, healing work of exposing and cleansing the wound. Maybe he would also bring healing to her family.

She would need to decide—and soon!—about her travel plans. Or maybe she would try to persuade her parents to visit her in West Michigan. She would turn forty on March first. Maybe she would invite them to come celebrate her birthday with her. She would love for them to have an opportunity to meet Nathan and his son, Jake. Or was that kind of introduction premature?

She exhaled slowly. So many unresolved issues to address before she returned to Chicago.

The driver in the car beside her at the traffic light held a phone in one hand, a coffee cup in the other. A few short months ago Hannah would have been shoveling raspberry yogurt into her mouth at stoplights or stalking a microwave because even minute rice took too long. Could she really duplicate the unhurried rhythm of her sabbatical once she returned to work? The slowing down, the paying attention, the deliberate rest and unplugging, the transition from the driven life to the received life—all of this was a paradigm shift she still needed time to process and integrate. All of this was a shift that would be severely tested once she reengaged with ministry. Now that the new year was upon them, thoughts about next steps would inevitably press in and demand her prayerful attention.

Her phone rang as she pulled into Meg’s driveway. Nate. “Hey!” he said. “Just checking to see what time you want to come over. I was thinking maybe an early dinner and game night before we go to the service.”

Hannah, who had never attended a watchnight worship service, was eager to join Nathan and Jake for their New Year’s Eve tradition. “I think I’ll finish up at Crossroads around two,” she said. “And then I need to pick up some things for Meg at the store.”

“So come after that.”

“What should I bring?”

“Just yourself.”

“At least let me bring a dessert or something.”

“We’ve still got lots of Christmas treats here,” he said. “Seriously. Just come.”

“I hate coming empty-handed.”

“I know, but it’s good for you. Think of it as ‘open-handed.’”

She could hear the smile in his voice as they said their goodbyes. Nate had a point, as usual. She still needed to practice receiving kind and gracious gifts with open hands. Good thing she still had a few months left to practice these new disciplines.

Her sabbatical, intended as a gracious and exceptionally generous gift, had initially seemed unkind, like a forced exile from the ministry she loved. But then, by the faithful and stealthy work of the Spirit, Hannah had begun to perceive all the ways she had hidden behind her busyness and productivity, all the ways her personal identity had been swallowed up and enmeshed with her professional one, all the ways she had defined herself by what she did for God rather than who she was to him—the beloved. Her senior pastor, Steve Hernandez, had seen what Hannah had been unable to see, and he had taken bold, drastic steps to give her the time and space to die to old, entrenched habits and fears in order to rise again to newness of life.

“I thought you were going to stay in bed and rest!” Hannah said when she entered Meg’s foyer, which was still brightened by a few Christmas decorations.

Meg, wrapped in a flannel robe and huddled over a steaming mug at the kitchen table, shrugged one shoulder. “Couldn’t shake the bad memories of being stuck up there sick when I was little, so I decided to come down here.”

The formality of the first-floor rooms—a parlor stuffed with antiques, an elegant Victorian-style dining room, and a music room where Meg taught piano lessons—weren’t conducive to relaxing. What Meg needed was a comfy couch or recliner. Hannah set down her shopping bag on the kitchen counter. “How about a change of scenery?” she asked. “We could go to the lake for a few days, stay at the cottage. I know Nancy wouldn’t mind me having guests there.” Nancy and Doug Johnson, longtime friends of Hannah’s at Westminster, had given her their family cottage at Lake Michigan for her sabbatical, another lavishly generous gift she had been reluctant to receive. “I’ll be out late tonight,” Hannah went on. “The worship service doesn’t start until eleven. But we could head there tomorrow afternoon.”

Meg appeared to be considering this.

“You’ve hosted me here,” Hannah pressed. “Let me return the favor. Please. I think some time at the lake would do you good.”

Meg sneezed against her shoulder. “Okay,” she said. “Thank you.”

Hannah lathered her hands at the sink. “I got you a couple of puzzle books to keep you going while I’m at Crossroads. They didn’t have a lot of art supplies, but I’ll head to the craft store later.”

“Please don’t—”

“Uh-uh”—Hannah held up her hand to cut her off—“we already talked about it. No backing out of play now.”

She sounded more like Nate all the time.

Hannah was waiting inside the entrance to Crossroads when Mara and Kevin arrived.

Mara embraced her. “Where’s Meg?” she asked, scanning the hallway as she wriggled out of her coat.

“Sick. Coughing, sneezing. She didn’t want to infect anybody here. I told her you’d understand.” Hannah unwound her scarf. “You’ll have to show me the ropes around here, Kevin. Your mom says you’ve become one of their favorite volunteers.”

Kevin’s fair, freckled skin flushed, and he looked down at his sneakers.

“I think Kevin’s working with the kids today,” Mara said. “Basketball in the gym, right, Kev?”

“Yeah.”

“We’ll be in the kitchen, Hannah, doing some prep work for lunch. Then we’ll help serve, if that works for you.” Mara’s phone beeped with a text. She reached up under her oversized lime-green sweater and tried to pull her phone from her snug jeans pocket, knotting her mouth and twisting her body to accommodate the maneuver. “Charissa’s on her way,” Mara said, glancing at the screen. “Says she’s running about half an hour late.”

Hannah was just glad she was coming. Ever since Thanksgiving, when Meg had joined Mara for her annual ritual of serving meals, Mara had anticipated the Sensible Shoes Club gathering at Crossroads. This was Hannah and Charissa’s first time visiting Mara’s old world, and Hannah knew how excited Mara was to share it with them. Maybe when Meg fully recovered, they could schedule another opportunity to serve together.

“Sorry I’m late!” Charissa said when she eventually entered the dining room. “Got a phone call from the realtor—everything’s fine—and then John had to get the snow off the car. We’ll be so glad when we’ve got our own garage. Five more weeks.”

“Glad you made it!” Mara set a plastic salad bowl down on the long rectangular table and pointed toward the coat rack in the far corner of the room. “Coats go over there, and you’ll need to pull your hair back.” She patted the net that covered her own dyed auburn hair. “Miss Jada will make sure you have one of these snazzy caps before she’ll let you touch any food.”

“Sounds good,” Charissa said as she took off her stylish royal blue wool coat. With her bulky Irish fisherman’s sweater, it was hard to tell whether Charissa had started to show any baby bump yet. She would be the sort of tall, thin woman who could conceal her pregnancy for months if she wanted to.

“You look good,” Hannah said when Charissa returned to the kitchen moments later. “You feeling well?”

Charissa tucked her long dark hair up into the net. “Finally, thank God. I think the morning sickness might finally be behind me. First trimester, done. But if you see me make a quick exit, you’ll know the smell of food overpowered me.”

“Just soup, salad, and bread today,” Mara said, motioning toward several large pots simmering on the stove. “They do their big meals on Sunday nights. Or try to, anyway. Miss Jada always says the loaves and fish will multiply, and they do. Somehow it always works.”

Once the guests began to arrive, the three of them took their places with other volunteers behind the long buffet table, Mara ladling soup, Hannah serving salad, and Charissa pouring drinks and not correcting people who read her name tag and mispronounced her name while thanking her.

Hannah eavesdropped as Mara warmly interacted with people who were obviously regular guests: Sam, wrinkled and toothless with naked women posing on his tattooed neck; Constance and her wide-eyed little girl named Lacey, who sucked her thumb while peering up at them from between her mother’s legs; and Rickie, a recently unemployed, single mom of three young boys, one of whom had evidently become attached to Kevin. “He’s in the gym,” Mara said when the little boy asked her if Kevin had come to play. “After you finish your lunch, you can go play basketball with him.”

Just as the queue of hungry people was dwindling, an elderly man entered from the parking lot door and took his place at the end of the line. Dressed in baggy shorts and a long-sleeve gray T-shirt, he stared at his sandals while holding his plate, a handwritten price tag dangling from a thread affixed to his cuff with a safety pin. “God bless you, sir. God bless you, ma’am,” he murmured to each volunteer as he trudged by. From her peripheral vision Hannah watched Charissa greet him, pour him a glass of water, and then engage in conversation Hannah wasn’t quite able to hear. The next time Hannah glanced over her shoulder, Charissa was gone, overpowered, perhaps, by the smell.

Charissa

Even a pregnant woman could spend only so much time in a restroom before friends grew worried. Charissa Sinclair was staring at the bathroom mirror, trying to fix her mascara, when Mara entered. “You okay?”

She had been doing great until the man with the shorts and sandals shuffled through the line, and then she’d lost her composure. Sub-freezing temperatures, eight inches of snow on the ground, and his only buffer against the cold was a dingy pair of tube socks. “They’ll help him, won’t they?” Charissa asked. “The man in the shorts—they’ll get him some clothes or shoes or something? You don’t think he’s actually living outside like that, do you?”

“Don’t know,” Mara said. “Miss Jada’s on top of it, talking to him now. Haven’t seen him here before.”

You look like my sister, the man had said to her. You ever live in Philly?

No, Charissa replied. She had never been to Philadelphia.

Last time I seen her, she was about your age. You could be her daughter or something. You a Monroe?

No, she wasn’t. Her mother’s maiden name was Demetrios. But she hadn’t told him that, in case he was a con artist trying to finagle security information.

The bathroom door creaked open. “Everything okay?” Hannah asked.

Charissa swept her hair into a fresh ponytail. “Just pulling myself together. The last one got to me. The shorts and sandals, that little price tag dangling from his sleeve.”

“Too bad Tom’s already cleared out his closet,” Mara said. “I would have loved bringing a whole bunch of his stuff here. Wish I’d thought of that sooner.”

Great idea, Charissa thought. The man was about John’s height and build, short and lean, and John probably had half a dozen coats in their hall closet. She could go back to the apartment, ask him to donate a few, and deliver them to Crossroads right away.

Funny, how she had lived in Kingsbury all her life and had never even heard of Crossroads before she met Mara. No—not funny. Sad. Before her parents moved to Florida, her father’s law office was located only three blocks from the shelter. Charissa could remember her mother’s firm, tugging grip whenever they bustled hand in hand from the parking garage to the office for a visit. Her mother always commanded her not to make eye contact and to ignore any stranger who spoke to her asking for money. Bums, her father called them. Nuisance, shiftless drunks. She had smelled alcohol on the breath of several of the—what did Miss Jada call them?—“guests” as they made their way through the lunch line. Point proved, her father would say.

But there was no cloud of liquor engulfing the elderly man, only the stench of urine and perspiration permeating his clothes and a look of despair consuming his dove gray eyes. Just remember, Miss Jada had instructed all the volunteers, everybody you meet is made in Abba’s image. If you can’t see it, look harder. Ask for new eyes.

So Charissa had focused on looking hard—praying to see—even while the dismissive, condemning voices clamored inside her head, the same voices that had once reviled Mara about her past. Now here they were, serving together as friends, proof there was hope for Pharisees to be converted to grace after all, even if the conversion process took longer than she liked.

When they returned to the kitchen, Miss Jada was supervising meal cleanup. Charissa scanned the dining hall. “Couldn’t get him to stay,” Miss Jada replied when Charissa asked about him. “He just wanted some food, and then he was on his way again.”

“Without a coat?”

“Didn’t have one to give him. Already gave away all the coats from the Christmas clothing drive. Had a pair of sneakers and trousers that almost fit him, so he took those. And a blanket.”

“But will he come back tonight or something? Did he say if he has a place to stay?”

“Honey, he knows we’re here,” Miss Jada said, patting Charissa’s shoulder. “That’s about the best we can do.”

Guess I was hoping you was family, the man had said to Charissa with a heavy sigh. Evidently, she had missed her opportunity to ask what had happened to his. If only she had been quicker on her feet.

“When are you coming back?” she asked Mara as they donned well-insulated coats in the foyer.

Mara glanced down the hallway toward Kevin, who was high-fiving a group of animated little boys. “Saturday, I think. Kev said he wants to come again before he starts school, and I’m gonna help with the lunch. Why? Wanna come?”

“Yes, maybe. I’ll check with John to see what his schedule is.”

Mara leaned forward to give Charissa a hug. “Forgot to say thank you,” she said. “For the donation you sent to Crossroads. Miss Jada gave me the card on Christmas. Never had anyone do anything in honor of me before. One of the best gifts I ever got. Thank you.”

“You’re welcome. I know how special this place is to you. I can see why.” Charissa was still watching the dining hall, hoping maybe the man would return, but the guests had cleared out, some of them back to the streets, some of them probably huddled on the sidewalk near her father’s old office.

“Tell Meg we missed her,” Mara said to Hannah when she came out of the restroom. “One of these days we’ll get the whole Sensible Shoes Club here together.”

“I know Meg would love that,” Hannah said, looping a loosely knit scarf several times around her neck. “And we also need to figure out whether we’re doing something together at New Hope or something else . . . some kind of next step. I want to keep moving forward. Deeper.”

“Amen to that,” Mara said. “I was looking at the retreat schedule for the spring, but I really don’t think I can manage it right now, not with everything so up in the air with Tom and the boys.”

Charissa had had the same thought. Between the house move and school and pregnancy and everything else going on over the next few months, she couldn’t commit to any more classes. But her childhood friend Emily was in a prayer group with women from her church, and when she and Charissa met for a power walk in the fall, Emily had spoken enthusiastically about their journey of spiritual formation. “I’ll check with a friend of mine,” Charissa said. “She’s been meeting with a group of women for a few years now, and maybe she’d be willing to share some details about what they’ve done together.”

“That sounds good,” Mara said. “Maybe we could meet twice a month or something.”

Charissa nodded. “I’d be happy to host, after we move into our house.”

Hopefully, Meg wouldn’t feel awkward about that. Though she had insisted she was looking forward to visiting her old home again, it might be difficult for her after Charissa and John redecorated. With John’s elaborate plans for kitchen and bathroom remodels, the house would be significantly altered.

On her way back to the apartment, Charissa drove to the 1920s cottage on Evergreen and parked in the driveway, the snowdrifts concealing the front steps. Just think, Riss! That front window there, that’ll be our baby’s room! John was the dreamer, often talking about “what it would be like when . . .” Charissa, on the other hand, had little time or imagination for such things. Most days it was enough for her to try to maintain some sense of equilibrium in the midst of all the dizzying changes that had occurred during the past couple of months. Thirteen weeks ago she was a PhD student with a fixed trajectory of achievement: she would be an English professor, and someday she and John might have a family. Now, that someday was a rapidly approaching July eleventh due date.

“Just make sure my parents know you’re grateful and excited,” John had reminded her on multiple occasions during their three-day Christmas visit with his family in his hometown of Traverse City. John’s parents, who had given them money for a down payment, had embraced the news of their first grandchild with unbridled joy. Charissa, meanwhile, had expended considerable energy keeping pace with their enthusiasm. After a joint outing to Home Depot—“Just to browse through some possibilities,” her in-laws had said—she’d been ready to throw a tape measure at something. “Humor them,” John mouthed to her whenever his mother expressed her opinion about paint colors or light fixtures, or whenever his father recommended particular woodgrain finishes and cabinets.

“It’s our house, right?” Charissa had hissed to John, who signaled for her to keep quiet. “Just checking,” she’d muttered.

She appreciated her in-laws. She did. Even if she didn’t share a lot in common with them. Judi, Charissa suspected, had never fully understood John’s choice of wife. She had never esteemed her daughter-in-law’s achievements, her intellect, her drive. Judi had devoted her life to her children, a stay-at-home mom who attended every Little League game, ran the Parent-Teacher Association, managed the Music Boosters, coordinated fundraisers, organized class parties, and regularly provided healthy, balanced family meals at the dinner table. To hear John tell the stories, the woman was a legend in Traverse City.

Charissa’s mother, on the other hand, was a top executive at a marketing and public relations firm, who had never volunteered at school because she worked full time. But she had attended every awards ceremony, beaming from the front row, and had monitored every achievement with pride. And many nights she had prepared delicious Mediterranean cuisine because cooking was her particular hobby, and she wanted to preserve her Greek heritage. To her disappointment, Charissa had not inherited her passion for food.

During their premarital counseling sessions, Charissa and John had been asked to explore family of origin issues and how their parents had shaped expectations of roles and relationships. They had discussed similarities to their parents (“Analytical and cool under pressure, like my dad,” Charissa said, “and driven, very achievement-oriented like both of them”) as well as differences from them (“My mom is really emotional, with a Mediterranean passion for life, and you always know when she’s angry because she’ll tell you. Loudly. I’m more stoic”). She and John had emerged from two very different parenting models, and while they had affirmed their own agreement about roles and responsibilities, it probably wouldn’t hurt to revisit their expectations, now that they were pregnant.

Her phone buzzed with a text from her mother: Call me.

Thinking of expectations . . .

Ever since telling her parents about the whole missing-her-final-presentation-of-the-semester fiasco, her mother had been determined to offer advice about how to rebuild her reputation, both with faculty and peers: You’ll have to redouble your efforts to prove yourself again, show them that you’re committed to this PhD program, that you’ll excel, no matter what, and that you won’t be slowed down by a baby. Take on some extra work; turn your presentation into a journal article or something.If you’re absolutely sure there’s no further possibility of appeal, you’ll have to do your best at damage control.We can figure out how to use this, how to spin it all for good.

What Charissa hadn’t told her parents—what she knew they would have no capacity to understand—was that she had begun to fathom Dr. Allen’s words about perfectionism being a form of captivity, that what she deemed a failure might in fact be a work of grace in her life to set her free from years of shame and fear. “Everything has the potential to shape us, either to make us more like Christ or to make us more egocentric,” Dr. Allen frequently reminded her on the loop inside her head. By grace she had begun to see—particularly over the last few weeks—her socially acceptable forms of idolatry: her thirst for honor and recognition, her pursuit of excellence for her own sake, her deriving her sense of self not from her identity as the beloved in Christ but from her own achievements and reputation.

“For freedom Christ has set us free,” she had read from Galatians 5:1 that morning. “Do not submit again to a yoke of slavery.”

Even when the gravitational pull toward that yoke exerted unyielding, relentless—and often well-intentioned—force.

She picked up her phone to text Emily—Do you have any resources from your spiritual formation group that you can share with us? We’re eager to continue the journey together and could use some suggestions. Thanks and Happy New Year—and pressed Send.

“You don’t need all these coats, do you?” Charissa slid the hangers in their apartment closet back and forth, the hooks clicking and scraping along the metal rod.

John looked up from the cardboard box he was cramming with books. “Like what?”

Charissa held up a tailored wool coat she’d seen him wear once.

“Christmas gift last year from my mom.”

“Do you need it?”

“Yep.”

She put it back in the closet and removed one of three heavy-lined jackets. “How about this one?”

He squinted at it. “From North Face? Yep—keep.”

“Okay, how about this?” A black one, not from North Face.

“Keep.” He dragged the packing tape dispenser along the top of the box and pressed the seal closed.

“This one?” she asked. John had been wearing this gray one since she’d met him in college, and it was tattered along the cuffs.

“Still fits.” He assembled another box, the tape squeaching along the seams.

“But do you need it?”

“We’ve got good closet space at the house, remember?”

“That’s not what I asked—I asked if you need it.”

He sat back on his heels. “I don’t need to get rid of it.”

“Fine.” She kept shifting hangers. “Then you come here and pick one, please. I’m trying to find something I can donate to Crossroads. They’re all out of coats, and we have a glut.” She chose two coats she hadn’t worn in a few seasons and flung them over the back of a chair. There might not be many five-foot-ten women in need, but the coats would be long and warm on someone.

“Take the black one, then,” John said.

She added the black one to the pile. “How about hats and gloves?” She held up a crate stuffed with winter accessories.

He rose to his feet and brushed off his jeans. “Tell you what. Here—I’ll work on the closet, you clear out the bookshelves.”

She traded places with him. Too bad all of her children’s books were at her parents’ house in Florida. Maybe she could purchase some used books at a thrift store. Mara had mentioned that Kevin enjoyed reading to the kids.

When John’s cell phone rang with the Star Wars theme, he strode into the kitchen to take the call. Though he didn’t speak a name, Charissa could tell after the first couple of sentences that it was his mother—again—offering another suggestion regarding the house. Curtains, carpet, floor rugs maybe. If Charissa had known that accepting the down payment would create the opportunity for her in-laws to exert jurisdiction, she might have refused the gift.

She unrolled some bubble wrap—not the unsatisfying miniature bubbles but the large, bloated ones—and popped a few between her thumb and index finger. John waved at her to be quiet, pressed the phone more tightly to his ear, and disappeared down the hallway.

Tossing the bubble wrap aside, she seated herself at the dining room table, opened her laptop, and checked email. Junk. Ad. Coupon for a manicure.

“I’ll talk to her about that,” she heard John say. “No, I know. Thank you. Just haven’t had a chance.”

Junk. More thoughts from her mother about how to restore her reputation. Ad. Junk. Message from Emily. Subject: Prayer exercises for your group.

“No, nothing’s final, Mom. . . . Not sure. End of the summer, maybe . . . mm-hmmm . . . right . . . no, I know. I appreciate that.”

Appreciate what? she wondered.

She drummed her fingers on her laptop before clicking on Emily’s message: Hey, Charissa! So excited you guys are going to continue your journey together! I’m attaching some prayer exercises to get you started. Our leader, Sarah, developed these with her mom for a class they led at New Hope a few years ago (you met Katherine Rhodes, right?), and she said she’s happy for me to pass them along to your group. It’s been a life-changing experience for us—amazing how the Holy Spirit brings the Word to life in different ways that speak right to where we need to be addressed. Let me know if you have any questions about anything. And let’s get coffee or lunch or a walk on the calendar—lots to catch up on!

John’s replies were becoming more clipped and cryptic. Evidently, he didn’t want Charissa discerning what was being said on the other end of the conversation. Great.

She opened Emily’s Word document and skimmed through it. Some of the exercises were ones they had done at New Hope in the fall during the sacred journey retreat: prayer of examen, praying with imagination, pondering images of God and how they are formed.

She could probably benefit by returning to the image of God exercise, not having given it much thought or prayerful attention a few months ago. She couldn’t even remember what she had written about. God as helper, maybe.

Yes. That’s the image she had chosen: the God who helped her succeed, the God who gave her strength and ability to achieve all of her own plans and purposes to the highest possible standard. She sighed. She definitely needed a less self-centered image as she inched her way forward toward deeper conformity to Christ.

“What haven’t you had a chance to tell me yet?” she asked when John entered the room. The startled look on his face indicated he wasn’t pleased she had overheard his side of the conversation.

“Nothing.” He shoved his phone into his back pocket and busied himself in the closet, rearranging hangers.

“Don’t play games with me, John. Just tell me your mother’s latest idea for us. Something about furniture? Carpeting? What?” Maybe someday he’d have the courage to tell his mother that while they were grateful for the gift, they were going to make their own decisions about what to do with it. If Judi had this many grand ideas about decorating the house, what kind of advice would she attempt to give once the baby was born?

“You don’t want to know,” John said, his voice muffled in the closet.

She closed her laptop. “Ummm, yes. I do.”

He emerged with a stack of scarves, hats, and gloves. “Don’t shoot the messenger, okay?”

She sat back in her chair, arms crossed, chin lowered, eyebrows poised and waiting.

“You know my mom, how she was, like, über-mom, involved in everything, always there for us, no matter what we needed, what we were doing. Her whole world revolved around Karli and me.” Which was one reason why Charissa was glad her in-laws lived two hours away. A little bit of distance provided a buffer zone that, for the first eighteen months of their marriage, had worked relatively well. But now that the first grandchild was on the way—

John set the clothes down on a chair and raked both hands through his thin brown hair, which, Charissa had recently noticed, had begun to recede like his father’s.

“Just tell me,” she said. “You’re making it worse.”

His hands were still pressed on top of his head. “She just wants to make sure our baby has the best possible life, wants to make sure we have the freedom to make the right choices, without financial pressure.”

Charissa narrowed her eyes at him. “And?”

“And . . . she said she hoped you didn’t feel pressure to keep going with the PhD at a frantic pace, hoped you felt free to take some time off once the baby’s born.”

She clenched her jaw. No wonder John hadn’t found time to talk to her about that yet.

He threw up his hands. “Like I said—”