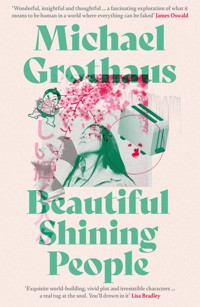

Beautiful Shining People: The extraordinary, EPIC speculative masterpiece… E-Book

Michael Grothaus

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

A damaged teenage tech prodigy meets an enigmatic waitress in a tiny Tokyo café, sparking an epic journey across Japan that will change everything, forever … a captivating, masterful novel with an extraordinary mystery at its heart… 'Set against a tech heavy backdrop Beautiful Shining People blooms into an emotional and soulful tale that reckons with the isolation we can all feel as outsiders' SciFi Now Book of the Month 'That Beautiful Shining People isn't just a slipstream novel with pretensions to being literature is in great part down to the deftness and tenderness with which Grothaus draws his central relationship … to let us explore a world of robots and deepfakes that's just unfamiliar enough to be exotic' SFX Magazine Book of the Month 'A fascinating exploration of what it means to be human in a world where everything can be faked … wonderful, insightful and thoughtful' James Oswald ––––––––––––– This world is anything but ordinary, and it's about to change forever… It's our world, but decades into the future… An ordinary world, where cars drive themselves, drones glide across the sky, and robots work in burger shops. There are two superpowers and a digital Cold War, but all conflicts are safely oceans away. People get up, work, and have dinner. Everything is as it should be… Except for seventeen-year-old John, a tech prodigy from a damaged family, who hides a deeply personal secret. But everything starts to change for him when he enters a tiny café on a cold Tokyo night. A café run by a disgraced sumo wrestler, where a peculiar dog with a spherical head lives, alongside its owner, enigmatic waitress Neotnia… But Neotnia hides a secret of her own – a secret that will turn John's unhappy life upside down. A secret that will take them from the neon streets of Tokyo to Hiroshima's tragic past to the snowy mountains of Nagano. A secret that reveals that this world is anything ordinary – and it's about to change forever… ––––––––––––– 'Poetically written, every word of this adventure leaps off the page with passion. A wonderful and enlightening trip' The Sun 'Cyberpunk meets bildungsroman – a real joy' Oscar de Muriel 'Exquisite world-building, this book had me invested from the very first page. Vivid plot and irresistible characters and a real tug at the soul … you'll drown in it' Lisa Bradley 'A life-affirming, epic book about what it is to be human: to live, to dream, to hope, to love … at a time when we most need reminding of these things' David F Ross 'Totally engrossing from the start – the story, characters and settings will linger in your imagination long after you're finished … truly wonderful' Jonathan Whitelaw 'Masterful … truly breathtaking and achingly beautiful. It builds anticipation and suspense before coming together in a thrilling, captivating conclusion' The Bookbag 'Outstanding! Sci-fi showing how the past might impact on the future … a glimpse into a (very plausible) terrifying future' Michael J Malone What readers are saying… ***** 'A beautiful, emotional and thought-provoking read' 'A striking and strange novel – and a searing statement about the dangerously thin lines between utopia and dystopia' 'Just devastatingly beautiful' 'My book of the year … no question' 'Masterful storytelling' 'Succinctly captured the feeling of Japanese fiction. I was very much put in mind of Haruki Murakami or Toshikazu Kawaguchi'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 671

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR BEAUTIFUL SHINING PEOPLE

‘Cyberpunk meets bildungsroman – a real joy’ Oscar de Muriel

‘A fascinating exploration of what it means to be human in a world where everything can be faked, and an alarming projection into a not-too-distant and all-too-plausible future … wonderful, insightful and thoughtful’ James Oswald

‘Totally engrossing from the start – the story, characters and settings will linger in your imagination long after you’ve finished … truly wonderful’ Jonathan Whitelaw

‘Exquisite world-building, this book had me invested from the very first page. Vivid plot and irresistible characters and a real tug at the soul … you’ll drown in it’ Lisa Bradley

‘Set in a near-future Japan where technology has all but rendered human productivity redundant, Beautiful Shining People is a life-affirming book about what it is to be human: to live, to dream, to hope, to love. And at a time when we most need reminding of these things’ David F. Ross

‘Outstanding! Sci-fi showing how the past might impact on the future; part coming of age, part boy meets girl, with a strong sense of place and a glimpse into a terrifying and very plausible future’ Michael J. Malone

‘A striking and strange novel, about beautiful shining people in all their strangeness – and a searing statement about the dangerously thin lines between utopia and dystopia’ B. S. Casey

‘Masterful … truly breathtaking, achingly beautiful passages of writing, from internal reflection to vivid descriptions of the surroundings. Grothaus’s second novel moves for the most part relatively slowly, ebbing and flowing smoothly as it builds anticipation and suspense before coming together in a thrilling, captivating conclusion’ The Bookbag

‘This book was incredible … I couldn’t bear put it down’ Sophia Eck

‘Devastatingly beautiful. It made me smile, it made me weep, it made me turn the pages faster and faster, holding my breath in suspense … quite simply immense’ From Belgium with Booklove

‘The story is underpinned by mystery and suspense, but it is so wonderfully textured and nuanced that it is also so much more … A truly beautiful story of friendship, trust and love, and it’s most definitely highly recommended’ Jen Med’s Book Reviews

WHAT READERS ARE SAYING…

★★★★★

‘Truly epic’

‘I don’t think I’ll ever get this book out of my mind’

‘The writing, the themes, are utterly beautiful’

‘A modern classic’

‘I am broken’

‘A master storyteller’

‘Extraordinary writing … this book is very, very special’

‘Thrilling … thought-provoking and so powerful’

PRAISE FOR MICHAEL GROTHAUS

LONGLISTED for the CWA John Creasey NEW BLOOD Dagger

‘Gloriously funny but dark as hell, you will laugh and recoil in equal measure’ Sunday Express

‘By turns comic and shocking, an extraordinary debut from a striking new voice’ Michael Marshall Smith

‘Complex, inventive and a genuine shocker, this is the very opposite of a comfort read’ Guardian

‘One of the twenty-five Most Irresistible Hollywood Novels’ Entertainment Weekly

‘Engrossing ... a captivating story that manages to be funny, sinister and surprising’ New York Daily News

‘A thrilling and highly original debut that cuts to the dark heart of celebrity and pornography. Michael Grothaus is one to watch’ Eva Dolan

‘Startling, inventive, funny and disturbing, compelling and oddly beautiful – Epiphany Jones is a novel that marks the arrival of a truly talented writer’ Kevin Wignall

‘The emotional range is astounding – Grothaus is an exceptional talent’ J. M. Hewitt

‘Grothaus writes with a delicate fluency that contrasts with the depravity of his subject matter. Humour and emotions: what more could you ask for in a thriller?’ Maxim Jakubowski

‘A real seat-of-the-pants read, and utterly uncompromising. It’s graphic, visceral, mordantly funny, thought-provoking and at times profoundly moving’ Raven Crime Reads

‘This is gutsy, courageous, crazy crime writing … A highly original debut that’s disturbing, funny, grotesque and brilliant’ Craig Sisterson

‘Tragic, brutal, shocking – and magnificent’ K. E. Coles

Beautiful Shining People

Michael Grothaus

For m.e. & k.n.

Contents

1 – The cusp of a new world.

Everything before me looks like another world, one normally hidden from the ordinary.

A patchwork of illuminated shapes stretches into the distance. The soft blinking of a thousand antennas. The drones silently gliding across the night. Behind them, glowing hues mist vast swaths of the landscape – a kaleidoscope of colours suggesting even stranger lands within this strange expanse.

Yet, as I look into the sky, I’m reminded that I’m solidly earth-bound. That this isn’t some otherly world I’ve been transported to. My eyes adjust to the two artificial stations, the jagged silver crescents suspended between here and the natural moon. One American, the other Chinese. Both locked in their endless, paranoid orbital dance, neither yet finished, but each already suspicious of its incomplete neighbour.

The sound of a bell sinks my eyes back to the infinite city before me. On the narrow side-street below, a man rides his bicycle, its basket stuffed with groceries. He rings his bell again, warning the stray cat lounging outside a FamilyMart to get out of the path. At the corner, a woman watches a stream on her phone as she waits for the bus. On the next street over, a car ferries someone through the Tokyo night.

Yes, there’s no mistake: this is the ordinary world with cats and convenience stores and a never-ending supply of content.

I glance at the time. Already quarter to eleven. Sleep seems futile, but I promised myself I’d try – so I at least have a shot of making the excursion I’ve missed the last three mornings. So yet again my lids don’t close as dawn is breaking. I step back into the apartment and slide the balcony door shut. I strip to my boxers and take a piss. At the sink with its too-large mirror, I brush my teeth. As always, my eyes stay focused above my chest.

I crawl into bed and tell the apartment to turn out everything but the bedside lamp.

The clock says it’s now an hour to midnight – but nothing, not a hint of tiredness.

This damn jet lag.

I pull my backpack from the floor and feel inside. My passport. The brochure. The paperback I’ve been reading. But it’s too cerebral. It’s the kind of novel that makes you think instead of making you sleepy. I need something dull. The magazine – the one the surgeon let me take this afternoon after his nurse noticed the person in the examination room was the person on the cover in the waiting room.

I’m not even sure what the publication is. Its language is set to Japanese. The cover shows the latest flagships from Samsung, Avance and Huawei, each rotating as Japanese script materialises and dotted lines grow and point out various features of the competing metalenses. But the cover scrolls, and it’s now the picture of me taken my second day here. I’m standing next to a hive of quantum servers. I’ve worn that sweater every day for the last three. Mercifully, the cover scrolls again, now showing some kind of agrarian bot – then the sequence repeats.

I give up trying to find the language setting and toss the magazine back into my backpack. I think of calling Mom, but instead, I take out the brochure.

The models in its photos look so joyful – but I guess that’s the point. On the inside flap, a good-looking man is frozen in a mid-air leap, about to spike a volleyball. And his smile … well, I’d have that smile, too, if I were in his body. But the doc was honest. Even post-procedure, it won’t look completely normal. Still … just hearing what could be done, I felt like I was standing on the cusp of a new world.

The cusp of a new world. An odd phrase, I know. Almost old-fashioned, yet it’s the one that popped into my head up in his office with its floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking Tokyo’s expanse. I was on the cusp of a new world in which I could be as close to normal as possible, as close as I’ve ever been to all those millions of people working and living and strolling around with each other on the streets below.

The surgeon wrote his fee on the last page in yen and dollars and said to contact him if I decide to proceed. I read the brochure twice more, then fold it closed and set it on the nightstand.

Sixteen after eleven.

I turn out the light and shut my eyes.

When I next spy the time, it’s eleven twenty-three.

Eleven thirty-nine.

At eleven forty-seven, red creeps across the room as silently as a shadow. Through the balcony’s glass door, I catch the dim safety light of a window-washer drone as it glides by…

Screw it.

I dress and grab my backpack. I take the elevator to street level. The October air is chillier down here than on my heated balcony. The trio of vending machines give me my bearings, and I turn and follow the maze of narrow pavements and pedestrian alleyways until I spot the 7-Eleven on the corner, where I make a left onto a main artery full of darkened restaurants with their plastic foods displayed behind panes of glass.

The mist of multicoloured light ahead signals the right direction. Yet despite all its metascreens blaring bright, when I reach Shibuya and its famous scramble crossing, I find even this part of Tokyo makes time for sleep. Bots doing janitorial work behind department stores’ locked glass or those doing street maintenance almost outnumber the people still out. I cross intersection after intersection, but the only places open seem to be noisy pachinko parlours or smoky bars. I realise I’ve circled the entire scramble when I come back to a Starbucks that’s been closed for an hour.

Terrific, I think, feeling like a batter who’s turned up long after the game’s ended.

Leaning against an empty bike rack, I pull my backpack’s straps tight and fold my arms across my chest. My eyes drift from the cars moving in sync, to a bot polishing the floor inside a Uniqlo, to a glaring meta ad for Docomo looping four storeys up on a high-rise across the scramble. And as the surrounding hues go from blue-purple to pink-orange, someone shrieks. It’s one of a pair of stragglers pressing their flapping coats against their bodies in response to a gust that’s struck as they’re crossing the scramble.

Are they out, fighting the wind, because of jet lag, too?

They make it to the other side as the streetlights go green and the cars waiting on the scramble’s edges recommence their journeys in perfect synchronisation, indifferent to the night’s conditions. All the while, the pink-orange glow of a gigantic cartoonish bunny creature advertising I don’t know what washes over everything. Yet soon, even its light gives way. Now the harsh white of an NHK clip featuring the day’s top story casts itself across all. The anchor mutely speaks as Japanese and English subtitles appear below him.

It’s about a scandal that rocked China last week. A party leader has been cleared of wrongdoing after a viral video showed him beating a prostitute in a hotel room, duct tape balled into her mouth. The footage caused outrage across the country, the subtitled anchor says, but Chinese officials say their investigation proves it was a deepfake created by ‘a foreign adversary’ to sow fury in Chinese society. The officials said a forensic deconstruction revealed the lighting on the man’s earlobe in a few frames wasn’t consistent with the air density in the room. It’s not something you could tell with the naked eye, or even with commercial detection software, but given time – just days in this case – the power of China’s AI allegedly cracked it. If it really was a deepfake created by a foreign state, the anchor says, it’s believed to be the first that’s broken into China’s intranet in over a year.

‘Konbanwa,’ a voice says.

It’s one of the few Japanese words I’ve memorised. It means, ‘good evening’.

The greeting is from a tourist-information bot that’s come to a stop at the end of the bike rack. They’re common in high-trafficked areas of Tokyo. It’s probably detected I’m sitting here looking a bit lost, so rolled on over.

I say hello, and it switches to English. It asks if I need help finding something or if it can call me a car.

‘I’m just out for a walk. Can’t sleep.’

‘A nice night for one,’ it says.

A nice night for one, I repeat in my head. It’s funny, I always assumed America had the most advanced bots, but Japan’s blow ours away. It’s partly due to their form. Like this one’s: its build is almost cartoony, like a mascot you’d see at a baseball game. Its domed digital face looks like an anthropomorphised cat with enormous eyes. In America, people-facing robots are plainer looking, appliance-like. Yet it’s not just their appearance that makes eastern and western bots different. In America, bots’ personalities are subservient; here, they’re programmed to speak as if they’re an easy-going acquaintance.

The tourist-information bot’s domed head reflects a shade of blue as a new ad on one of the buildings mists the area in novel light. The bot’s big cat eyes blink.

‘Hey,’ I say, looking down upon its arced face, ‘are there any quiet places in the area where I could sit and kill some time?’

The info bot’s big cat eyes blink again. ‘There are fifteen clubs, thirteen restaurants, eleven hotel bars, six sports bars, three cigar bars, and one jazz bar currently open in Shibuya, all of which offer seating. Eight of those bars, six restaurants, and five clubs will close in the next hour.’

‘But like somewhere quieter? Like a coffee shop or café where I could have some milk tea and read a magazine until I get tired?’

This is now the longest conversation I’ve had with anything but the surgeon in days.

‘I’m sorry, I’ve checked, but there aren’t. The last coffee shop closed forty-two minutes ago. But twenty-three coffee shops open at six a.m., followed by fifty-eight others at six-thirty a.m.’

‘And there’s not a single café open right now, either?’

‘Unfortunately not. The average closing time for cafés in the Shibuya area on a weeknight is between ten and eleven-thirty p.m.’

I nod but don’t say anything. Across the scramble, a gigantic girl blinks to life along the length of a glass skyscraper. She’s soon joined by three other giants, all members of the same J-pop band. Their lips move, silently belting their latest hit, available for streaming now.

Two of the girls leap from the skyscraper’s surface only to reappear on the surface of the department store opposite, where their gyrations continue.

‘Can I help you with anything else?’ the info bot says.

I shake my head. ‘Not unless you know a trick for falling to sleep.’

‘I’m sorry, I don’t.’ Its digital eyes blink. ‘Sleep isn’t something I’m acquainted with.’

‘No, I suppose not.’ I let out a breath. ‘Well, it’s getting colder. I guess I’ll head back to my apartment,’ I say as a way of goodbye to the robot.

‘Of course. Stay warm and have a good night.’ Its domed head shifts down, as if bowing.

I give it a little smile and rise from the rack. Yet I haven’t taken more than a few steps when I hear it:

‘You’re on the cusp of a new world.’

The words stop me in my tracks.

You’re on the cusp of a new world.

I turn back. The info bot hasn’t moved.

Its short body glows a deep green, bathed in the light of a new ad.

‘What’s that…?’

But in that green glow, the bot remains silent. Its only reply, a blinking of its cat-like eyes.

I glance around. No one else is near.

‘What did you just say?’ I try again.

A cold gust whips over us, but for several moments there’s only silence.

Finally, the bot replies.

‘Stay warm and have a good night,’ it says, its eyes blinking a few more times.

I stare for a moment longer as a shift in the light darkens the air another shade. In the eerie glow, the bot’s cat-like eyes blink once more, yet it doesn’t speak again.

My jet lag is making me hear things.

I cross the scramble and turn up a street parallel to the one I took here, leaving the gaseous glow of Shibuya behind. As the street curves, the last of the hues behind me fade, and with them, any illusion of warmth. I give a shiver and pull my backpack’s straps tight across my shoulders, shoving my hands into my pockets.

A gust rustles the trees lining the darkened street. All the shops I pass are closed, their insides dim, and after a few moments I realise I’m the only one around.

Before me, a fallen leaf scratches along the sidewalk, blown by the October breeze. The tips of its dried body curl downward like brittle fingers attempting to stop its involuntary locomotion. It flips over, again and again. And just as I’m sure it’s about to blow out of my sight, its crisp body smacks against something.

It’s one of those sandwich board signs eateries put up outside – the kind with an embedded chalkboard where the day’s special is written.

I’m not sure what the top portion says, as it’s written in Japanese, but on the bottom there’s an anime-ish drawing of a man’s face laid sideways, an instrument inserted into his ear. His chalk face looks serene. Content even. Next to the drawing is the message: Relaxing Ear Cleaning – Only ¥4900.

The board’s in front of a detached two-storey building. The banner above reads MR. HAPPY CAFÉ in white letters on a red background. A warm glow emanates from the door’s glass pane, and I spot what looks to be the edge of a counter with someone behind it. I can’t tell for sure, though, because a coat hangs on the rear of the door, blocking most of the view. There’s another window to the door’s left, yet a curtain’s pulled across it.

I step back. Taking in the building as a whole, I can’t help but feel it looks out of place. Its pinkish-peach colouring isn’t tacky exactly, but it’s nowhere close to mirroring the chic appearances of the better-kept establishments it neighbours. Still, from my new perspective, I can now tell someone’s definitely behind the counter in the foyer. I can see an arm through the unobstructed slice of glass. And the window to the right reveals an additional dining area separate from the foyer. The dining area’s empty, but its lights are on.

The thing is, I’ve walked this street a dozen times in the week I’ve been here, yet never recall noticing this place. Then again, I’ve never been out this late, and all the other times the street’s been packed. It probably just never caught my eye through the crowds.

I look at the sandwich board again, the dried leaf still pushed against it in the now-howling breeze. The tourist-info bot definitely said all area cafés were closed – yet this one’s lights are on, someone’s inside, and their sign is still on the sidewalk.

A tiny bell clangs as I enter. As its resonance fades, a perfect stillness replaces it, as if someone’s found the mute button for the room. But the foyer’s stillness only amplifies the strangeness of what’s before me. Behind the counter, the biggest Japanese man I’ve ever seen stares at me. Scratch that. The biggest man I’ve ever seen. His jet-black hair is tied up into a bun. Minimum he’s six-four, yet it’s his added width that makes him so massive. He’s easily twice as wide as me, shoulder-to-shoulder. And he’s gotta be four hundred pounds. At least. Yet it’s an odd four hundred. Definitely a lot of fat, but the bulk of his shoulders and chest suggests he could bench press an ox without breaking a sweat.

But the big man isn’t the oddest thing staring at me. That would be the tiny, white geometric dog sitting on the counter. At once adorable and surreal, the dog’s hair has been styled in such a way that its head takes the shape of a perfect sphere two sizes too large for its body, the surface of which extends to the tips of its snout and ears, so much so that they no longer have any depth. The thin black lines of its mouth, its tiny coal-black eyes and its small, wet, black dot of a nose might as well have been drawn onto a snowball with a marker. Below its collar, the dog’s midsection is cut short to better call attention to its head, which, really, is so perfectly spherical it looks like you could pop it off and roll it across the floor.

A pair of scissors hovers above the dog’s head, suspended mid-air by the big man’s meaty fingers. For several moments, both keep their gazes frozen on me like they’ve been paused by the same remote that’s muted this room. Soon though, the dog cocks its head, trying to regain the big man’s attention. And as if my novelty has worn off, the big man returns his scrutiny to the circumference of its head, inspecting individual hairs and deftly clipping any even a millimetre too long, just like an experienced gardener prunes uneven branches from a hedge.

‘Ah, konbanwa,’ I say, almost surprised sound does carry in here.

The big man stops clipping the dog’s hairs and looks at me again. His expression is so flat I can’t say he’s ‘studying’ me. It might be better to say his expression is one of complete indifference – the way someone looks at a brick wall they’re standing next to while having a smoke. After another moment, a sigh escapes his mouth.

He says something, but I don’t know what.

‘I’m sorry,’ I say. ‘Do you happen to speak English?’

He answers with silence. That flat expression isn’t changing. On the counter, the dog gives a sharp yap, regaining his attention. He sets the scissors down and picks up a purple comb with just three long, thin teeth. He plunges the trio of teeth into the dog’s cotton ball head and fluffs the hair outwards, then repeats. The dog seems to greatly enjoy this.

Without looking at me, the big man says something. It sounds like the same thing as before, but I can’t be sure.

‘I was wondering if I could do the ear cleaning?’ I try, twisting my hand by my ear, miming a swabbing with a Q-tip.

This time the big man stares at me like an audience member thoroughly unimpressed with the show. As he recommences the dog’s fluffing, he calls out unrecognisable words in a voice so deep it must be what a blue whale would sound like if it could speak.

He goes perfectly quiet again – all focus on the dog’s sculpting.

In the muted awkwardness, my eyes flit around the foyer. Next to the door is a narrow ledge and stools. A chalkboard menu hangs over the counter. Behind it, an open partition exposes the kitchen. The foyer opens into the small dining area. Two booths sit next to the window overlooking the street. Across from them is a coffee table and couch. And between the couch and the foyer is an entrance to a hallway so void of light it’s as if it’s not even part of this world.

But nowhere is there anyone else he could have been speaking to.

‘I guess you don’t do it this late…’ I say, now just feeling stupid.

But silence. Total silence from the big man as he continues teasing the dog’s hair without giving me so much as another glance. The dog seems just as oblivious to me. It squints with such pleasure, the primping of its hair so relaxing, it may very well be on the verge of passing out. Lucky little guy.

‘Well, sayōnara,’ I say turning for the door, my fingers grasping its cold brass handle.

The voice that replies out of thin air is so soft I bet its algorithmically possible to demonstrate it’s the exact opposite of the previous bellows. ‘Konbanwa,’ it says.

But any thoughts of algorithms leave my head when I turn back. Inside my chest something contracts into a fist so tight, for a moment, I forget to breathe.

The girl’s materialised in the invisible plane where the foyer and dining area meet. Her straight black hair flows to her shoulders, and her bangs barely conceal the dark brows resting above eyes so astonishingly clear, they’re like the blue-grey of rain. The light pink of her lips rest in a perfectly neutral position, neither smiling nor frowning, neither agitated nor amused. But it’s those eyes that hold all the power. They hold me for several soundless moments until I hear a distinct sigh.

I’ve become visible to the big man again, who now gives me a hard stare.

Shit. How long ago did the girl say ‘Konbanwa’?

I clear my suddenly dry throat. ‘Ah, sorry, I don’t Japanese. I was walking and then came here. I asked him, but we couldn’t talk … There’s the ear-cleaning sign outside I saw, and I wanted to see if I could get it,’ I say mostly those words in mostly that order to the girl.

It’s the jet lag speaking. And nerves. I also threw in the universal gesture for Q-tips, which I now sorrily regret.

In the renewed silence, the girl studies me as if I’m some kind of still life. And then, though her lips remain perfectly neutral, I can’t help but think I notice her smile. It’s because of how her eyelids shift. Their edges curve downward ever so slightly, like tiny crescent moons.

‘Hai,’ she says with an abrupt nod.

I barely manage to stop myself from replying with an English ‘hi’; and I think she notices – the edges of her lids curve again, and I feel my face warm.

She motions for me to take a seat on the couch in the dining area. As I make my way, I feel the big man’s gaze stalk me across the room. The walls in here are covered in framed pictures. Most, old-timey travel ads. I sit and fluff my sweater out around my waist as the girl disappears into that hallway so void of light it might as well be a black hole. With the big man still eyeing me, I turn my attention towards a rack of unusual sweatshirts at the couch’s far end. They’re identical. All navy blue and all featuring a cartoony shark made of felt, launching itself from the wearer’s torso. The sweatshirts’ pockets hang outwards, like pectoral fins. A sign reads ¥7400.

From where I’m sat, the lighting turns the window by the booths into a mirror. I give my hair a tussle in its reflection and flare my sweater a bit more upon hearing the girl’s returning footsteps. She exits the hallway’s void, engrossed in the contents of a shoebox. A small pillow is wedged under a bare arm, her sleeveless denim dress following her slender body down to her ankles. She sets the pillow at the far end of the couch and kneels before me. At such proximity, I notice that a tiny trio of light, faint moles dot her face. It’s as if they were put there because nature simply refuses to allow perfection to exist. Still, any way you look it, she’s striking.

‘It’s my first ear cleaning,’ I say just to say something.

The girl gives a sharp, affirmative nod, thankfully unable to tell I’m just blabbering.

How old is she? Older than me, but not by much.

She sets the shoebox on the floor and then gestures with both hands, running them in an up-and-down motion in front of her bare shoulders.

‘Oh, right,’ I say, realising I’m still wearing my backpack. She places it next to the rack of shark sweatshirts. As I lay down, I again fluff my sweater out around my waist. In the shoebox are instruments that look like long toothpicks, cotton swabs, and other items.

When I’ve settled, she says, ‘Hai,’ as a way of asking if I’m ready. I return a little confirmatory nod.

Fishing into the shoebox, she retrieves a moist wipe and gently rubs my ear, pulling on the lobe before working deeper. At first, it feels weird, but soon it’s actually pretty nice. But the problem is my eyes. I’m not sure where to set them. I’m staring straight ahead, yet because of where she’s positioned, that happens to be at the swell of her breasts beneath her dress. I shift my gaze towards her face, but now I just feel like a Peeping Tom watching a beautiful girl carry out her work, which she’s thankfully doing with such focus it’s keeping her from noticing my predicament.

That’s when a cold disquiet hits me: is this something only perverts do here? Getting a pretty girl to clean a part of your body? I don’t think it is … but what if I’m wrong? Then again, she’s the one giving the cleaning, so she can’t think it’s too creepy.

As she readjusts and starts into my ear canal with a long toothpick-like instrument, I spy one of the framed pictures on the wall. It’s a smaller one, and jagged around the edges, like it’s been ripped from an old magazine. It’s monochrome too, the digital ink long dried up. In it, a young, massive Japanese man with a beaming smile sits cross-legged as he holds a large fish up by its towel-wrapped tail. Next to him kneels a short, slightly stocky woman, who gazes in admiration as she claps joyfully. Behind the pair, others applaud.

But that’s the final thing I see, because I can’t help shutting my eyes as the girl works deeper into my ear. Her soft, careful touch and the tool’s gentle scraping are so relaxing – within minutes I’m drowsy.

The last memory I have of my dad is from nine years ago – the night before he and Mom went to Angola. I was eight, and we were sitting on our front porch, legs swung over the concrete steps, watching the blazing pink Midwestern sunset. I’m not sure where Mom was – probably inside with Grandma, packing. Since he and Mom were going to be away for some time, Dad told me I’d need to be good and help my grandparents around the house. Every day I did my chores they were going to give me a quarter. ‘By the time we’re back, I know you’ll have been so helpful this piggy bank will be full,’ said Dad.

We called it a piggy bank even though it was just a big pickle jar. Already it had about an inch’s worth of coins – previous rewards for doing my chores. Every month Dad stopped at the remaining bank in town to pick up some old physical money, for no other reason than this. I asked him how much was in the piggy bank now, so I’d know how much more I’d have earned by the time Mom and he returned. We dumped the jar onto the porch and spread the coins flat between us. Even now, I remember the way he observed my small hands arranging them. His gaze was full of such warmth – I haven’t seen anything close to it in anyone’s eyes since.

Dad slid one old coin at a time from the main pile into a new one as he counted the sum out loud. ‘Five … ten … thirty-five…’ Each coin slid across the porch’s concrete made a pleasant scratching sound, which, when combined with Dad’s deep voice, produced the oddest sensation in me: a warm, tingling feeling bubbled up and exploded inside my skull, as if my brain was floating in a container of heated seltzer water. That feeling extended down my spine and into my arms as Dad continued to slide and count the coins. Soon my entire body was cocooned in this tingling warmth, and I fell into a deep sleep. Dad had to carry me up to my bed, and it wasn’t even dinner time yet.

It remains to this day the most euphoric sensation I’ve ever experienced.

In the time since, I’ve had similar instances where someone can make me feel warm and sleepy – even if it’s in the middle of the day. Usually, it happens when someone is speaking or doing something gently very close to my head, like when I’m getting a haircut or going to the eye doctor for a check-up. It’s why I came in here. I thought maybe an ear cleaning could have a similar effect. Maybe it could get me tired and help reset my internal clock – jet lag be damned.

And you know what? I was right. By the time the striking girl has me flip over to do my other ear, I’m so sleepy she could disrobe in front of me and it wouldn’t even register. When she’s finished the cleaning, she even needs to shake me a little.

My eyes open to find hers looking over me, the edges of their lids curved in that invisible amusement. I feel like I’ve awakened into another world, I’m so relaxed.

I pay the big man at the counter where the dog with the spherical head sits, neither seeming strange anymore. Even the short walk back to my apartment in the crisp October air doesn’t rouse me.

And the last thing I see as my head hits my pillow is the infinite city’s twinkling lights stretching beyond the balcony’s glass door.

It’s a city still shrouded in night, and it will continue to be for hours to come.

2 – Japan is good.

‘I’m sorry,’ I say to a maintenance bot carrying out minor curb work. I’ve bumped into it after glancing the time on my phone. It’s just after eight p.m. and I’m headed back to my apartment, hoping my missing backpack is there. Hearing my apology in English, the bot replies, ‘No worries,’ and I turn the corner onto my apartment’s street.

This morning, when I woke, it felt as if I’d been in a long, dense hibernation and for several moments I stayed motionless in bed. The fine particulates of atmosphere floating among the rays of light flooding the apartment were captivating, and as their microscopic bodies swayed overhead, I couldn’t help thinking something was peculiar about the way they were illuminated – almost as if the photons adhered to some unknown physics that had developed in secret while I slept.

I rose, slid open the glass door and stepped onto the balcony.

It wasn’t just the rays of light in my room – the whole world looked different.

Then I saw the time, and it hit me why: I’d never seen Tokyo in the nine-a.m. light.

Or the 9:09 a.m. light, to be precise.

I dressed and flew out the door. It was the first day I’d managed to wake in time; there was no way I was going to miss it again. I weaved so quickly through the crowded streets I reached Shibuya Station in half the time it should’ve taken. And despite the station being an endless tangle of paths and corridors, punctuated by indecipherable signs among a jungle of people, bots, stores, trains and buses, I caught the 9:45 tourist shuttle to Hakone.

My guide app listed Hakone as the best daytrip from Tokyo – just ninety minutes away. For the most part, the journey was unspectacular, but for the last thirty minutes, the shuttle skirted a bay and then the terrain became mountainous as we turned inland. During this stretch, an elderly couple across the aisle struck up a conversation about how beautiful the water looked. They asked if I’d been in Japan long and where in America I was from. They were Canadians, and it was their first time in Asia. We chatted off and on, but when we reached the station at the mountain’s base, we became separated as everyone formed into packed lines for the cable cars. The one I boarded was filled with Chinese tourists who had arrived via another shuttle.

The cable car took us over yellow pits bellowing sulfuric clouds. They’re Hakone’s most popular attraction – though one girl in my car almost fainted from their smell. She had to sit, and someone covered her nose and mouth with a damp cloth. The car dropped us at the mountain’s summit, where we wandered the vast observation deck with good views of the yellow slopes. I took the obligatory pictures most everyone was taking, then rested my elbows on the safety railing and gazed at the plumes for a long time.

It occurred to me how clear-headed I felt. The fog of jet lag had finally lifted. I thought of the girl from the café. Her sleeveless denim dress and her clear, blue-grey eyes. I suppose I had her to thank for my slumber.

At one point, a priest from a Vietnamese tour group offered to take a photo of me overlooking the pits. I think he realised I was alone. I don’t like to be in pictures but stood for one anyway and thanked him. I emailed it to Mom and told her I was having a blast, then rode a cable car to the opposite base of the mountain, where it met a massive lake, and I boarded a ferry for a cruise. It was all part of the package. Besides, it was something more to do, at least – to fill all the time I have. Out on the lake, I took in the views and spotted a striking orange gate in the waters just off the shoreline.

That’s when it hit me: I didn’t have my backpack. I couldn’t remember where I would’ve taken it off on the observation deck. And then I realised I didn’t even have it on the shuttle. Had I left it at the apartment in my rush out the door? Or did I leave it in the café after the ear cleaning? I was so sleepy when I left, and the girl had asked me to remove it. There was nothing valuable inside. It had the novel I’d been reading and the magazine from the doctor’s office. But my passport was in there, too.

It was almost four when the ferry reached the other end of the lake, right as rain clouds crept over the mountain. I followed the other tourists across the docks to the parking lot where we were to meet our rides; but once there an attendant announced an issue with some of the shuttles’ nav systems and said we’d need to wait another hour for replacements. The ones that finally arrived were the old-school kind that required an actual driver – and it meant I didn’t return to Shibuya Station until almost eight.

I enter my apartment. The morning’s peculiar rays are long gone. Through the balcony’s door, only the artificial lights of the infinite city can be seen, though their glow is muted by the moist air that’s followed from Hakone. My backpack is nowhere to be seen.

I throw on a hoodie and head back out. The leaves rustle as the café’s pinkish-peach exterior comes into view, but a weight hits my chest as I notice the sandwich board isn’t on the pavement. Have they already closed? Some little establishments here keep irregular hours – staying open late some nights, while randomly shutting early on others.

Yet as I near, the weight on my chest lessens. A man steps from the café carrying a brown takeaway bag. He inspects the night sky for a moment as the stiff breeze hits him, then pulls his collar up. Through the window, I see a group of students in one of the booths. A couple of middle-aged women are on the couch where I had my ear cleaning – only they’re chatting over coffee.

The door’s bell clangs as I enter, and my eyes immediately go to the dog with the spherical head perched on the counter. Despite the eternal surrealness of the dog’s geometry, the café has a distinctly different feel tonight. There’s no stillness in the air and no muted silence. The world outside and the world in here are indistinguishable.

The dog’s wet nose gives a sniff, and it greets me with a double yap that cuts through the chatter from the dining area. In response, the big man turns from the open partition that shows into the kitchen. He holds a plate in each hand, both bearing quartered sandwiches and small cups of soup. His eyes lock onto me but as always, his expression is flat. It’s like he’s chronically displeased.

He sets the plates on the counter mere inches from the dog, yet it doesn’t so much as sniff the food, which is all the more surprising since, even from where I stand, it smells delicious. The big man eyes me for a moment more before his attention turns towards a small scratchpad on the counter. A second later, he bellows words I couldn’t hope to understand in no particular direction at all.

‘Konbanwa … I was here last night,’ I say, drawing his attention again. ‘I did the ear cleaning.’ And I mime a Q-tip in my ear. I bring my fists to my shoulders and move my hands as if I’m adjusting invisible straps. ‘I think I might have left my backpack here?’

The big man’s flat expression doesn’t budge. Not one millimetre.

But as I drop my hands, something catches my eyes – a few flecks of brightness in that dark hallway that sits between the foyer and dining area. A sharp breath later, the girl materialises from its void like an apparition.

Unlike last night, every inch of her body is now concealed below the neck, from the ends of her ankle-length grey skirt to the collar of the black, long-sleeve T-shirt. Even her hands are covered by shiny, white gloves that run underneath the cuffs of her T-shirt all the way up to her elbows. I can see where their outlines end under her sleeves. They look almost theatrical; the kind you’d buy at a cheap costume shop if you were starring in a grade-school play set on the fashionable boulevards of nineteenth-century Paris. It’s these shiny gloves that were the bright flecks in the hallway’s darkness. And they bear my backpack by its straps.

‘Konbanwa,’ the girl says, smiling a soft, inviting smile that’s replaced last night’s neutral lips. And with that smile a fist again contracts inside my chest and I feel the air go just a little bit thin. She holds the backpack towards me like she’s a curator presenting a delicate artifact.

‘Arigatō, arigatō,’ I say, taking it. ‘Thank you so, so much. I was worried I’d lost it.’

And even though she can’t understand what I’m saying, she smiles politely and occasionally nods as I ramble that I went to a mountain, and there was a boat, and that’s where I realised I didn’t have my backpack. I go on, telling her how on the way back, the weather started looking bad, and I thought it would be a good idea to check my apartment first, but the backpack wasn’t there.

It’s like that fist inside my chest is squeezing every last word from me like juice from an orange.

Regardless, I thank her again for keeping my backpack safe. Then I thank her for the ear cleaning. ‘Japan is good,’ I say for some reason. And as I’m running out of ramblings, the one thing I’ve thought most this entire time slips from my tongue before I can stop it:

‘You make me wish I spoke Japanese.’

The edges of the girl’s eyelids curve down into that invisible little smile.

Oh, God.

‘It’s OK,’ she says. ‘We can stick with English.’

That fist squeezes so tightly, my heart feels pulped.

Behind the counter, the big man seems to wonder, How does this idiot get through the day?

‘I’m glad I could look after your backpack for you.’ The girl gives that welcoming smile, ignoring the big man’s gaze and, mercifully, whatever mortified look I’m wearing.

‘I’m so sorry…’ I breathe. ‘I assumed … last night, I was really jet-lagged. I just assumed you didn’t speak English.’

I don’t even want to know how red my face is.

‘It’s no problem,’ she shakes her head. ‘I’m just happy you came back. I hope you don’t mind, but I looked inside after I found your backpack. I thought something in it might have the address of a hotel. When nothing did, and when I saw the passport, I hoped you’d return.’

Behind the counter, the big man lets out something between a sigh and a grumble, which the girl disregards, instead keeping her gaze on me.

‘Would you like some food? Have you eaten?’ she asks. The big man says something. He sounds annoyed. And from the counter, the dog yaps. She ignores them both, keeping that soft, inviting smile on me. ‘I can bring you a menu.’

I manage a little smile, which goes a ways in helping me shrug off some embarrassment. ‘Food would be great.’ Truthfully, I’m not hungry, but I don’t want to be rude. She saved my backpack, after all. Besides, what else do I have to do?

I slide into the empty booth by the window. At the counter, the big man speaks in short sentences, which the girl answers even more concisely. She grabs both plates from the counter and delivers them to the women sitting on the couch, then she brings me a menu. At the next booth, the group of students leaves, and another group takes the seats.

I order some scrambled eggs, toast and a coffee. It’s easy to choose because the menu has pictures. It takes some time for my meal to arrive. Though the café’s small, there’s a lot of foot traffic, with more people coming in to order something to go than staying and sitting. It seems like it’s just the two of them working here. The girl’s obviously the waitress, but she also spends time in the open kitchen, preparing some of the orders. The big guy spends as much time preparing food as he does operating the register. As for the dog, he just sits on the counter. Almost everyone who comes in laughs at his haircut, and many take a photo.

Though it’s busy, the girl stops by my table often and even seems to be giving me more attention than the other customers. Or maybe that’s not really the case. When we find people attractive, we usually delude ourselves into thinking the attention they give us is beyond what others receive. She offers to refill my coffee and asks how my meal tastes. ‘I like breakfast food at night, too,’ she says.

When I next spot her, she’s at the counter, packing an order. Her fingers seem to be having a problem with the small clasp on a takeaway container’s lid. She tugs at her gloves, pulling them on more snuggly, and tries again. It’s something I’ve seen her do repeatedly tonight – fiddling with her gloves – especially when picking up thin utensils while clearing a table. They actually seem to be an annoyance to her. I don’t know why she wouldn’t just remove them. They’re too fancy to be hygiene related. Besides, the big man isn’t wearing any, and he makes most of the food.

Customers cycle in and out as I finish my meal. I sip my coffee, turning my attention to the weather outside, where Tokyoites scurry past with their transparent umbrellas. There’s something oddly soothing about the way the rain forms a patchwork of small dots on the window, some of which break and merge with others to fashion a web of intricate streams.

It’s now a quarter after nine. When the girl returns, I ask if it’s OK to get some work done on my laptop – or if she needs the table?

‘Stay as long as you like. I’ll bring you more coffee. Do you want to try some dessert?’

‘Sounds good. What do you have?’

‘Goeido’s specialty is an ice-cream dish. Want to try?’

That must be the big man’s name. ‘Yeah, why not?’

At the counter she gives him my order and he gives me a look before retreating into the kitchen. A few minutes later, the ice cream is in front of me. It’s a big vanilla scoop with two smaller scoops set evenly apart at the base. A pair of round pieces of liquorice on the big scoop resemble eyes, and another bit resembles a small, black nose. Two lines of chocolate sauce form a mouth. When taken as a whole, the big vanilla scoop looks like the counter dog’s spherical head, and the little scoops look like its tiny front paws.

‘Brilliant, huh?’

‘The similarity’s remarkable,’ I say.

She returns to the foyer to welcome more customers, their shoulders damp from the rain.

Ice cream consumed, I fold my phone out into a laptop. Mom hasn’t replied to my earlier email, and there’s another message from Sony’s hospitality coordinator asking if I need anything to make the apartment more comfortable. After responding, I launch my dev tools, working at a leisurely pace. Occasionally, I’ll pause to watch the rain, or whenever the girl returns to refill my coffee and give me that kind smile.

But at one point, that smile fades.

It happens at the next booth. The customers are middle-aged salarymen used to eating late. As she clears their dishes, one says, ‘arigatō’, and she replies with a short word, pleasant smile and nod. But as she turns towards the foyer, two of the salarymen share smirks and a quiet laugh as the other whispers while gesturing like he’s putting on an invisible glove.

His hands are suspended mid-air when the girl turns back. In an instant, that pleasant smile dissolves from her lips. Retrieving the forgotten chopstick, she casts her eyes down.

I pretend like I didn’t notice any of it either.

A little after ten, the last customer besides me clears out, and when the girl comes to clean the table, I ask if they’re closing.

‘Hai, but it’s OK. I’ll be cleaning for a while, and it’s pouring outside. Stay as long as you like – I’ll bring you more coffee.’

So that’s what I do. Besides, being in a cosy café on a rainy Tokyo night beats sitting in the apartment again. Once she’s finished in the dining area, the girl mostly sticks to the kitchen, where I occasionally glimpse her and the big man through the open partition. Sometimes they’ll say short things to each other. Sometimes it even sounds like they’re bickering. But after just a few days in this country, I’ve realised that even the most benign conversations in Japanese can sound argumentative to an outsider.

After some time, the big man exits the kitchen. I feel his gaze as he approaches. It’s like he suspects I’ve got the gold coins from his hidden safe no one should know about stuffed into my pockets. Thankfully, he turns, and that dark hallway swallows him whole.

The kitchen lights go out, and the girl wipes down the counter after placing the dog on the floor, where I notice a little bed below the register. The dog circles several times before settling into it. After locking the front door and shutting off the exterior lights, she squats to pet the dog, speaking softly to it. When she rises, she pours herself a coffee.

‘I’ll go now,’ I say, about to fold my laptop down as she enters the dining area. ‘Thanks for letting me stay so long.’

But she sits across from me.

‘It’s OK. It’s still raining, and I’m not in a hurry. It’s just good to get off my feet.’ And she takes a sip from her mug.

I don’t say anything, but right now I wouldn’t leave this booth if it were on fire.

She takes another sip and looks out at the rain. Brushing her bangs with a gloved finger, she brings the mug back to her lips, where it hovers. Her eyes study me over its rim, but she doesn’t say a word.

‘I guess you close earlier tonight?’ I say just to break the silence.

‘We were closed when you came last night. Goeido just forgot to lock the door and bring the sign in.’

‘Oh … I’m sorry.’

She shakes her head. ‘It wasn’t a problem.’ And she holds her eyes on me for a moment more before finally sipping from her hovering mug.

‘Ah, I’m John,’ I say. ‘My name’s John.’

‘You don’t go by—’ and she says my first name.

‘How’d you—?’

‘Your passport, remember?’

‘Oh, yeah. Of course. No. Only teachers called me by my first name. And Mom, when she got angry with me when I was younger. But I’ve preferred my middle name for years.’

‘Why?’

I don’t know how to answer that, so I just shrug. Mercifully she doesn’t press me on it.

‘I’m Neotnia.’

That’s a pretty name, I want to say. Instead, I say, ‘Well, it’s nice to meet you.’

She nods then sets her mug down and peers over the top of my screen with an inquisitive grin.

‘So, John, what have you been working on all night?’

‘Oh … ah, just a pet project I got the idea for after I arrived. A translation app.’

‘Aren’t there a lot of those already?’

‘But this one isn’t like any of the others. Well, if I get the code right.’

She doesn’t reply. Clearly, she’s expecting me to elaborate.

‘Ah … well, so most translation apps work by using a built-in bilingual dictionary, right? They recognise a spoken word and literally translate it into the selected language using that dictionary. But because they’re coded using classical code – telling a computer the information via each bit that’s either a one or a zero – those apps don’t really have the versatility to adapt to the way people actually speak, especially in real time. The code’s binary nature limits their capabilities – so they’re not advanced enough to sense context, or things like sarcasm or the nuances of an individual’s speech patterns. But you might be able to get around those limitations with quantum code…’

This is usually where even Mom’s eyes would begin to glaze over, but Neotnia takes a sip from her mug without looking at it, her gaze locked on me like I’m revealing the meaning of life.

‘Uh … so with quantum coding, you’re writing for qubits instead of bits. Whereas a bit can be either a one or a zero, a qubit can be a one and a zero at the sametime, which greatly expands the computational power and … Well, in short, with the right code, a quantum-based translation app could learn on the fly as you use it. It could detect how each individual is talking, identifying their tones and inflections and the context in which they’re speaking. That could lead to it recognising things like sarcasm and such. Basically, it could result in quicker, more accurate translations, and allow two people who don’t speak the same language to better understand each other.’

Neotnia’s eyes remain bound to mine for several moments.

Outside, the rain makes new dots on the window.

‘That sounds very cool,’ she finally says.

‘Thanks.’ I give a shy smile. ‘Honestly, I got the idea because I’ve been in Tokyo for about a week now and was relying on the usual translation apps to get by. But they work too slowly or are too inaccurate, so people get impatient or offended or don’t understand what you’re really trying to say. But anyway, who knows if my app will work? I’m just playing around.’

‘So, that’s really you on the cover then?’ She nods towards my backpack. ‘Sorry, I didn’t mean to pry. I saw the magazine when I found your passport.’

‘Ah … yeah. That’s me.’

‘Woooow.’ Neotnia draws out the word with a smile. ‘And that’s why you’re here? Japan is full of computer scientists, but if Sony brought you all the way from America you must be really good.’

‘I don’t know. I only got into quantum coding a few years ago. Its duality – I just liked how something could be two things at once.’

‘Well, the magazine seems to know.’ She gives me a grin. ‘It says you’re a boy genius. How many people are called that? Not to mention, Japan’s biggest company is buying your app…’

My face goes warm at the word ‘boy’.

‘I just don’t think I’ve been doing it long enough for anyone to accurately label me as anything,’ I shrug. ‘And, you know, I was fortunate to even have an opportunity to learn to quantum code. Most people don’t.’

‘Oh? Why’s that?’

‘Well, it can’t run on classical computers, like our phones – they just don’t have the hardware capabilities. And many governments now restrict the technology anyway – an organisation needs to be licensed to even own quantum hardware. But my high school partnered with a big research university in the state to let us take a stab at using their quantum hive. So, the first thing I wrote was this app that could increase a phone’s battery life by manipulating its classically coded power-management systems with my quantum code. The head of the university’s quantum lab urged me to open-source it, which ended up getting me some attention from the tech blogs. But none of that would’ve even happened if I wasn’t lucky enough to get the opportunity to access quantum hardware in the first place. Anyway, what I learned from coding that first app, I applied to writing what Sony is buying. But it’s not actually an app – it’s just a quantum algorithm.’

Neotnia scrunches up her mouth a bit. ‘OK. So, what does a company do with this algorithm?’

‘Whatever they want, kind of. It allows high-end quantum servers to find patterns in exabyte-sized data sets exponentially faster than contemporary algorithms. So, you can use that in any number of fields: AI, finance, e-commerce, gaming, social, meta, you name it – anything where you need to identify sequences or trends hidden in massive amounts of data.’

‘And Sony wants it. That’s really cool.’

‘Yeah…’ I feel my face blush. ‘Well, a few companies actually approached me after I uploaded a proof of concept. It was kind of surreal, actually.’

‘Surreal? How many wanted it?’

‘Twenty-one.’

Another grin spreads across her lips. ‘That’s a little more than “a few”.’

‘Yeah. I don’t know why I said that.’ I clear my throat and give what’s probably an awkward smile. ‘Besides Avance, they were all foreign. ThaiX and LG were interested in it for search and meta. NEC and Samsung for communications and social. Avance too, until they dropped out. Lots of hedge funds were interested in it for trading. But, well, Sony actually hasn’t bought it yet. I guess it takes the lawyers a long time to do their due diligence and get the international regulators to sign off. It’ll be another three weeks or so before we sign the papers. I think their PR people are doing these cover stunts in the meantime so I don’t back out. They know other companies are interested.’