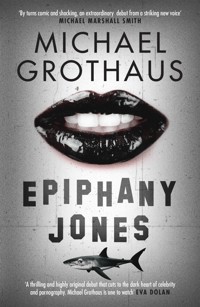

Epiphany Jones: The disturbing, darkly funny, devastating debut thriller that everyone is talking about… E-Book

Michael Grothaus

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

A traumatised young man forms a relationship with a young woman who believes she's gtting messages from God. Involuntarily entangled in the world of Hollywood sex-trafficking, they embark on a quest for revenge and redemption that will have devastating consequences… 'Gloriously funny but dark as hell, you will laugh and recoil in equal measure' Sunday Express 'By turns comic and shocking, an extraordinary debut from a striking new voice' Michael Marshall Smith 'Complex, inventive and a genuine shocker, this is the very opposite of a comfort read' Guardian **LONGLISTED for the CWA John Creasey NEW BLOOD Dagger** **Entertainment Weekly's 25 Most Irresistible Hollywood Novels** ____________________ Jerry has a traumatic past that leaves him subject to psychotic hallucinations and depressive episodes. When he stands accused of stealing a priceless Van Gogh painting, he goes underground, where he develops an unwilling relationship with a woman who believes that the voices she hears are from God. Involuntarily entangled in the illicit world of sex-trafficking amongst the Hollywood elite, and on a mission to find redemption for a haunting series of events from the past, Jerry is thrust into a genuinely shocking and outrageously funny quest to uncover the truth and atone for historical sins. A complex, page-turning psychological thriller, riddled with twists and turns, Epiphany Jones is also a superb dark comedy with a powerful emotional core. You'll laugh when you know you shouldn't, be moved when you least expect it and, most importantly, never look at Hollywood, celebrity or sex in the same way again. This is an extraordinary debut from a fresh, exceptional new talent. ____________________ 'An energetic, inventive, gritty and deeply moving thriller cum dark comedy, Epiphany Jones addresses the challenging subject of sex-trafficking in a powerful narrative driven by exceptionally well-drawn, unforgettable protagonists' The Bookseller 'Engrossing ... a captivating story that manages to be funny, sinister and surprising' New York Daily News 'A thrilling and highly original debut that cuts to the dark heart of celebrity and pornography. Michael Grothaus is one to watch' Eva Dolan 'Startling, inventive, funny and disturbing, compelling and oddly beautiful – Epiphany Jones is a novel that marks the arrival of a truly talented writer' Kevin Wignall 'A scabrously funny and thrillingly original book about atoning for past sins and indiscretions' David F. Ross 'The emotional range is astounding – Grothaus is an exceptional talent' J M Hewitt 'A truly impressive debut … a twisting tale at the same time realistically gripping and sardonic. Grothaus writes with a delicate fluency that contrasts with the depravity of his subject matter' Maxim Jakubowski 'A real seat-of-the-pants read, and utterly uncompromising. It's graphic, visceral, mordantly funny, thought-provoking and at times profoundly moving' Raven Crime Reads 'A cross between dark comedy and hard-hitting reportage, pulling together a tense, gripping narrative, unusual but strong characters, and a powerful message … outrageously entertaining' Crime Review 'One of the best debut novels I have read this year … a very clever thriller about murder, abuse, revenge and unadulterated evil. Sheer genius' Shots Magazine

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 620

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Epiphany Jones

Michael Grothaus

For m.e. And for the figments that live in our heads at three in the morning.

Contents

1

The Dream

Tonight I’m having sex with Audrey Hepburn. Audrey’s breasts are different from the last time we fucked; they’re bigger, not as firm. There’s a hint of a stretch mark on the left one. The leading lady is bent over, gripping the bedpost. Her pink panties are slid down and pinched in place by the fold where her legs meet her ass, so my rod has the most access with the least possible effort. She’s looking back at me, eyes sparkling and fixed, with a slim PR smile. I’m going like a jackhammer, sweating, shoulders cramping, but her face is as placid as a sleeping bunny.

And I’ve got to slow down; it’s only been three minutes. But who am I kidding? So I let it all out as I gaze at Audrey’s face. And for eight seconds I’m calm, relaxed.

There’s a loud crack under my foot. It’s Emma’s picture. My little sister. My sweet, dead little sister. My thrusting must have knocked it off the desk. I always turn her around when I do this. No matter how old the photograph is you don’t want the image of someone you used to know watching you while you squeeze one off. The cracked glass has scratched Emma’s face. She’s now got a little white-cotton scar over her right cheek.

For the next three minutes I straighten the items on the desk.

Seven minutes after that I’m hiding all traces of fake celebrity porn from my desktop. Just in case my mom comes over.

Then. when I notice it’s four in the morning, I get that guilt. Why did I do this? I have to get up in three hours, for God’s sake! I tell myself I won’t do it again. I promise. I pinky swear, you know?

And look, maybe you pretend you’d Never Do Such Things; that you’d never stoop so low as to jerk off to actresses whose heads have been pasted onto a porn star’s body. But this is better than seeing prostitutes or shooting heroin. It calms me down. It’s harmless. Besides, it’s temporary. It’s just what guys do when they’re on a break from their significant others. And anyway, the best part of these late-night jerk-off sessions isn’t even what came before, it’s what comes next: the clarity that comes after the guilt fades; the realisation of everything that’s wrong in your life and the vow you make to change it.

I need to lose weight. I need to be more outgoing. I need to save money. I need to get a better job. I need to, I need to, I need to.

This clarity is like the previews for next week’s episode – the promise of new, exciting adventures to come. It’s the trailer of what you can do to improve your sorry life.

But tonight the clarity doesn’t happen. Just like the last few weeks. No big ideas. No Nirvana. My life feels like a rerun.

I know how tonight will end. I won’t fall asleep for too long. When I do it will come again: that same dream I’ve had for the last three nights.

And yes, it is odd to have exactly the same dream night after night.

And no, I don’t know what the meaning is.

When it begins it’s black and I can’t see anything, but I can feel my mind floating through the nothingness. Then, slowly, a figure fades in. It’s a young girl. Fourteen, maybe fifteen. Her frame is petite and doesn’t fully fill the light-blue dress she is wearing. Her face is small and round. Her hair, pulled back tight around her head, is black like a raven’s folded wing. Her skin, white as cream. And curiously, her left ear is mutilated. It looks like a piece of her lobe was torn right off.

And for some reason, I know she is The Deliverer.

But I don’t know what that is.

We’re in a silverware factory, of all places. The factory is abandoned. Teaspoon after teaspoon rusts in boxes on roller conveyors. Forks dangle from strings overhead. Three furnaces fill the far corner of the room. Their mouths gape, revealing long-extinguished insides. Behind them, scorch marks on the brick walls. The floor planks are stained dark.

There’s a hint of a cleft in the girl’s chin and a slight tremble to her lip. The soles of her pale feet are black with dirt and dust and soot. She looks around frantically.

And I feel for this girl. She’s terrified.

She’s terrified because there are people coming. Bad people. I hear them outside, the people coming for her. Their silhouettes cast quick blue shadows as they dart past the windows, cracked and yellowed from chemicals and soot.

It’s early evening. Outside, crickets scream in the tall grass. The strangers thunder at the tin sidings. They rip and howl and shout in bizarre tongues as they claw at boards nailed over a doorway.

And inside, this little girl, she just stands in place now.

And a voice is heard: ‘An awakening is needed in the west.’

And the girl, she begins to cry.

Then they’re in, the strangers. Faceless forms charge her. I know they’ll kill her. I look away, there’s nothing else I can do. But when I look back, the girl has grown. Now she is maybe twenty-something. And I would think her beautiful if she weren’t so terrifying. Her smile is crooked and cold. Her eyes beget madness. She has a sickle in her hand. It’s funny too, because it looks just like the Nike logo. And swinging this Nike Swoosh, she kills the first three men.

Swoosh!

There goes one head.

Swoosh!

Another.

Just Do It.

And as she’s shortening people one by one, I start to focus on the dark hollow of the central furnace. I see something that leaves me feeling helpless and empty. I see myself hiding in the darkness of the furnace’s belly. I’m curled up, naked and crying. I’m seventeen years old.

And I’m praying not to be seen.

2

Van Gogh

I wake feeling like I haven’t slept.

The TV mutely plays an episode of Mr Ed. Wilbur and the talking horse are in astronaut suits. It’s the one where Mr Ed tries to convince Wilbur that they can build a ship to the moon. And why not? If your horse can talk, it sure as hell can build a space shuttle.

I reach for a balled-up dirty sock on the floor and spy a lone yellow pill sunk into the carpet next to it. So I do have one left. I really should take it.

I really should do my laundry, too. Tomorrow. Both tomorrow.

I stumble into the kitchen and grab the box of cereal with a white cartoon rabbit on the front. The microwave clock shows just how little time I have. I spoon my breakfast into my mouth, but by the time I get to the museum I’m still twenty minutes late. The moment I step into the Grey Room my boss starts complaining.

‘I need that Chagall done by eleven.’

‘Sorry, Sir. I was jerking off till five in the morning,’ would be the honest thing to say. But this guy, he probably hasn’t got it up in twenty years. He wouldn’t understand.

‘Sorry, missed the bus.’

‘Today is the last time you miss the bus. Understand? By eleven,’ he orders and walks back into his office.

I turn on the Mac. It’s got a grey desktop that perfectly matches the grey walls and grey everything else in this room. No wonder I’m depressed.

I’m a Colour Imaging ‘Specialist’ for the Art Institute of Chicago. It’s my job to make sure all the paintings you see in those art appreciation textbooks nobody could give a damn less about have accurate colour representation – so the periwinkle blues actually look periwinkle blue and the Venetian reds, Venetian red.

And let’s get something straight about my title. There’s nothing ‘special’ about me. Nowadays companies will throw ‘specialist’ or ‘consultant’ into any job description. It’s their way of tricking you into thinking you’re important.

But a ‘specialist’ is one step above a peon and a thousand levels below anyone who matters.

Same thing goes for all you ‘consultants’. Let’s be real, you don’t advise your company about anything. You’re a salesman. You’re Willy Loman and you’ve already got one foot in the grave.

‘Hey, buddy,’ Roland calls out before he’s even in the room. ‘Here’re more negatives for that Chagall. Donald wants them by eleven, I think.’

No joke.

‘Thanks,’ I say, powering on the scanner. Roland looks like a failed male porn star: a little too old, a little too thin, a little too boney. Most disturbing though is that he shaves his arms every day. He does this so everyone can clearly see his stupid sleeve tattoo, which runs from his wrist to his elbow. And I swear to God, I’ve never seen him without his shirt sleeves rolled up.

‘Hey, you want to see it?’ Roland asks with the excitement of a twelve-year-old who’s just found his father’s nudies.

‘They’ve brought it to you?’

Roland grins.

‘I can’t. I’ve got to get this done.’

Roland shakes his head. ‘Check it out with me. It’ll take five minutes.’

My sleep-deprived mind doesn’t have the power to argue, so I follow him down the hall to his photo studio. What would normally be a thirty-second walk takes minutes because of all the plastic sheeting and disassembled scaffolding in the hall. This whole wing is a mess because of the renovation of the museum. The whole time I’m glancing over my shoulder to see if Donald is going to storm out and bust me. The whole time Roland keeps jabbering about ‘It’, his voice wriggling through the sludge in my head like a tapeworm.

And when we finally get to his studio there It is, on an easel, just like it probably was a hundred and ten years ago. It’s small: eleven inches by eight inches.

‘Careful!’ Roland shouts. He’s caught a tripod I bumped into. ‘That’s ten million dollars right there.’

That’s all I need. Donald would end me if I damaged a painting. The tripod, it’s this old thing from the seventies. The MiniDV camera makes it top heavy. Its plastic legs are fractured in places. Anything heavier than the camcorder would snap it.

The way Roland is looking at me, he’s wondering how I get through each day.

‘Why don’t you get the museum to get you a decent one?’ I say.

‘I’ve tried,’ Roland answers like I shouldn’t have even needed to ask. ‘The renovation is cutting budgets from every department.’

The thing with Roland, he’s friends with my mom, and that’s where he gets it. Everything he says to me has a ‘you should know this’ inflection to it.

Roland’s desk is cluttered with fading flash screens, digital-camera card-readers, a week-old Sun-Times and books on outdated versions of Photoshop. But at least he’s got a fairly new Mac. The one they make me work on barely gets by. Sticking out from under a pile of old prints is a Hollywood Reporter with a picture of Penelope Cruz on the cover. And out of the corner of my eye Roland is giving me a pompous smirk. He pretends to himself that he knows what I’m thinking.

Above his mess of a desk is a framed article that’s clipped from the Chicago Tribune. In the article there’s a photo. In it Roland stands next to Donald and the director of the museum. All three wear stupid Masters of the Universe grins. In the right-hand corner there’s a picture-in-picture of the Van Gogh right next to Roland’s ridiculous face. And, OK, maybe I am a little bitter. He helped the museum obtain the Van Gogh. It’s on loan from the private collection of his old boss. It’s why he got the raise over me.

Behind me, I can feel Roland staring. He thinks I’m envying him. But you know what? I have nothing to envy. I’m in that picture too. Go ahead, if you look closely enough, in the opposite corner behind the director’s elbow, right there in the background, right where the caption starts you can see me behind the ‘– IZED’, hunched over my computer. The caption reads: ‘PRIZED WORK COMING TO THE ART INSTITUTE. (FROM LEFT) DIRECTOR DAVID LANG, DONALD GENTRY, AND ROLAND PEROSKI.’

‘It’s the first self-portrait he did after he lopped off his ear,’ Roland says, all high and mighty.

You can’t tell that from the painting. It’s a profile from the left. Van Gogh looks so sad. But at the same time, for someone who was so depressed he put a lot of colour into it. Bright specks of yellows, greens, reds and blues fill the painting. His hair is orange and his eyes a kryptonite-green. You can see the manic in them.

And here, Roland goes into bragging mode. He starts stroking the top of the canvas like it’s a cat. ‘The boss thinks this painting alone will attract an extra forty-thousand visitors in the next few months,’ he says. ‘So many museums wanted to get this piece, but none of them had the right connections. The real interesting thing is that…’

And I quickly lose interest. Lack of sleep makes my head feel so hollow my thoughts bound around the room like leaping sheep, before my eyes come to rest on his desk and the Hollywood Reporter with Penelope Cruz on the cover.

Maybe what I need right now is a pick-me-up. Maybe I can borrow the magazine and take a quick trip to the bathroom.

‘Hey, buddy? Jerry? Hello?’ Roland is saying. My thoughts snap back to him. He’s still standing by the painting, absentmindedly rubbing his finger over the top of the canvas. You can tell Roland’s an ex-Hollywood guy. He needs all the attention on him and his ‘accomplishments’. When he doesn’t have that, he’s one of those guys that fake concern that because you aren’t paying attention to him there must be something wrong with you. ‘Hey, buddy, you OK pal?’

And that’s when I think, fuck it, and decide to tell him about the dream. He’s an artist after all. Maybe he knows what a silverware factory symbolises in dream-speak. But I might as well be talking to myself. Before I’ve hardly begun, Roland’s solely focused on the painting again, a short stroking of just the same one-inch section of the top of the canvas, as if he’s found an invisible pimple he’s considering popping.

The painting isn’t that big a deal, I yell in my head.

In my head I say, No one cares about fine art anymore.

In my head I say, You’re so full of yourself.

So with Roland engrossed in his own glory, I edge over to his desk and take the Hollywood Reporter with Penelope Cruz and slowly roll it up and put it in my sleeve.

But with him stroking the canvas and me with my jerk material shoved up my sleeve, this is just getting awkward. So I say, ‘Hey, what’s with the camera crew outside?’

He says nothing.

I say, ‘Roland?’

And he says, ‘Oh, yeah – they’re doing some story on how the museum’s renovation is way over budget.’ Then, as if starting to snap out of his trance, he says, ‘Hey buddy, I should get started on this.’

And feeling the magazine rolled up in my shirtsleeve, I agree. I tell him I better get those Chagalls corrected, but he’s already shut the door behind me.

Back in the Grey Room I’m all alone. Donald is at his weekly ten a.m. with the museum board. That gives me the privacy to lock the door.

And a little after eleven I give Donald the colour-corrected TIFFs. I tell him I’m going to lunch. I need to get out of this grey prison.

3

Figments

I grab my venti double latte and the Sun-Times and take a seat by the window. Today’s headlines:

‘Alleged Child Rapist Beaten to Death by Victim’s Father’

‘14 Die in Palestinian Suicide Blast’

‘Archdiocese Settles in Sexual Abuse Charges’

‘Kraft Lays Off Additional 6,000 Factory Workers’

And just as I begin to feel better about my own life, I catch something from the corner of my eye: the girl with the mutilated ear. The older, beautiful, terrifying version of her. She’s standing on the sidewalk, just on the other side of the glass door.

But I blink and when I open my eyes again, she’s gone.

And I guess this is as good a time as any to explain something to you. What I just saw, the girl from my dream, the one from the silverware factory, the one standing right outside the door just now? She wasn’t real. She’s just another figment of my imagination.

Look, to me this feels so long ago, and I still don’t even remember half of it, but I’ll tell you about it anyway. This was way back years ago when I was seventeen. This was the night my father and I were in the Explorer. But this was still five years after Emma died. Five years after I began to zone out on TV and movies. Five years of my mom and dad seemingly forgetting how to say her name. Five years of referring to her death only as ‘What Happened’. I mean, why talk about my little sister when you could just pretend she never existed?

Back then my dad was one of the most powerful public relations people in Hollywood. And on this night Dad and I were driving to one of his Hollywood studio parties. A wrap party for some forgettable film called … well, I forget. Dad said he wanted me to meet ‘the gang’. I think he just wanted to impress me. He knew how many movies and television shows I watched and wanted to show me that he was part of that world. Or maybe he was just trying to make up for not being around much. He and Mom didn’t talk much after What Happened.

Most of the people at the party were behind-the-scenes guys: producers, executives, distributors. His group, the PR people, was there too, including an underling who worked for my father for years and who I’d never met. I can’t even remember his name. And, of course, Roland, shaved arms and all, was also there – but back then he called himself ‘Rolin’. He was the PR photographer at the time and believed that all photographers had to have cool names if they wanted the celebrities to trust them. In Hollywood it’s not what you create that matters, it’s the image you portray, and ‘Rolin’ with tattoos conveyed serious artistic talent levels of magnitude greater than ‘Roland’ from the Midwest.

‘Hey, come here,’ Rolin called over to my father and I when we arrived. He rolled up his sleeve. ‘Check this out. My latest. Cool, huh?’ It was da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man on his inner forearm. He looked like he was skinned alive. Rolin’s blood dribbled through where the ink had been injected earlier in the day.

I don’t remember much else about the party, but my shrink says that’s normal. He says, given after what happened next, it’s reasonable for my brain to try to block memories from that night. It’s my mind trying to save me from more hurt.

But I do remember what I wish my mind would let me forget. After the party, driving home through our subdivision, the Orange County air was warm and smooth as it flowed in the car windows. My dad seemed lost in thought, so I just listened to the crickets as they creaked and watched the curbs slide past, dipping and breaking every time there was a driveway. Suddenly there was a sharp swerve and a pop. I was jerked forward and the seatbelt snapped something in my chest as our vehicle stopped cold. I looked over at my father. The way the windshield was embedded in his skin, thousands and thousands of little shards of glass, his face sparkled like a mask of diamonds. I had never seen anything so magnificent. Then blackness crept in.

I woke to the horn. The windshield was gone. The steering wheel was in my father’s chest. I remember trying to scream, but couldn’t. Nothing was coming out. Someone was by the car. Blackness again.

‘It doesn’t look good,’ a voice said when I woke at the hospital. I thought they were talking about me, but they meant my father.

Our car hit a large maple. The impact was so forceful part of the engine ended up in the back seat. I was the lucky one. Broken collarbone. Bruised arm. Three weeks of physical therapy. The next day, when I woke, my father was dead.

Maybe I looked like an asshole to all the doctors in the hospital because I wasn’t all torn up and crying about things. But after Emma I had learned how to compartmentalise my hurt so well that I no longer remembered how I should feel when someone else close to me died. So I just lay in my hospital bed and held my mother’s hand as she shuddered and cried.

The funeral came and went. I was given my father’s gold watch to remember him by. It felt more like a retirement gift. Thanks for your service, son.

A few weeks later I met a girl. It was when, as usual, I went to a movie by myself. As fate would have it, Rachel chose to catch a flick on her own that day too. She was seventeen and had just moved to LA for a modelling contract with Cosmo. We hit it off right away, and though her work kept her busy, we were soon seeing each other. She was gorgeous: slim body, perky tits, anime-red hair and green eyes that would have matched the Van Gogh’s eyes perfectly, now that I think about it.

One night Rachel stopped by while my mom was out grocery shopping. I brought her up to my room and started to undress her. Truth be told, it was the first time I had ever seen a girl naked.

I can still feel how hard her nipples were, how soft her cheeks felt. Her hair smelled like Snuggles Fabric Softener.

I laid Rachel back on my bed and kissed her belly. She slowly arched her hips as I peeled off her mauve lace panties. I slipped a condom on and clumsily began thrusting.

She was so beautiful. Her little moans so comforting. Her breath on my neck so warm. She was perfect. Barely a minute had passed and I already wanted to cum. In her, on her – it didn’t matter.

That’s when Mom walked in.

‘Mom!’ I screamed.

‘Jerry, what is this?’ Mom yelped, her jaw long and her eyes wide in mortification.

And to Rachel, I yelled, ‘Cover yourself up!’ But she just lay there: legs spread wide, a perfect grin on her perfect face.

That’s one thing about being a supermodel: you know you’re so beautiful it just doesn’t bother you if total strangers see you naked – even your boyfriend’s mother.

‘Oh, Jerry, oh Jerry,’ Mom kept saying. ‘What are you doing?’

To Mom I yelled, ‘I didn’t think you were home!’

And to the pillows on the bed I yelled, ‘Rachel, get dressed!’

But that’s one thing about being a bunch of pillows: they don’t have to do what anyone tells them.

And just before I blacked out, Mom asked, ‘Who’s Rachel?’

Rachel, it turned out, was a figment of my imagination. That’s the name my psychiatrist gave it: a ‘figment’. A hallucination, a symptom of psychotic depression, maybe as a result of my father’s unexpected death. Or maybe, my father’s death, coming right after Emma’s, was the thing that made me snap. Who knows?

Mom told the shrink how I had stacked the pillows like they were a person. Two duck-feather ones for the torso, decorative pillows from the couch for arms, a couple of body pillows for the legs. My mom feared the worst. But my shrink stressed that I wasn’t schizophrenic. ‘Psychotic depressives invent people to fill voids,’ the shrink said.

What void? My mom didn’t dare ask.

‘Psychotic depression and schizophrenia are two different things,’ the shrink told us. He said schizophrenia is a slow road into hell. It’s not reversible. Psychotic depression is. ‘With regular counselling from a mental-health professional and some Zyprexa we can rid Jerry of these figments,’ he explained in his Harvard Medical Journal voice from behind a large oak desk. ‘Your son will be good as new in no time.’

Mom looked like she really didn’t believe it.

‘Are you sure the medicine will make him OK?’ she asked.

‘If not, there’s always electroshock therapy. That can help.’

‘My poor baby,’ my mom said, like the treatment was inevitable. Me, I was reading between the lines. I wasn’t going to get laid by a supermodel any longer.

‘And what other things should we keep an eye out for? Besides the seeing people?’

‘As long as he stays on his meds, nothing major,’ my shrink told her, like I wasn’t in the room. ‘Maybe some disassociation. Some minor anti-social behaviour. Perhaps a small inclination – less than one percent of psychotic depressives get this – but perhaps a small inclination to other rare disorders.’

‘Such as?’

‘Really rare stuff. An inclination towards things like Stockholm syndrome.’

My mom whimpered.

‘Relax,’ my shrink tried to reassure her. ‘Just make sure he’s never kidnapped and he’ll be fine,’ he winked. And to me he said, ‘But seriously, be sure to stay on the medication or the figments could come back. And you don’t want us to have to treat this with shock therapy.’

I took my meds religiously and saw the shrink once a month. I saw Rachel less and less. Another difference between being a schizo and being psychotically depressed: you know your hallucinations aren’t real once someone points the first one out. It makes them a lot easier to ignore. And though the medicine seemed to be working, my imaginary supermodel began to be replaced by very real stomach cramps.

‘I want to try a new medication,’ my shrink said the next time I saw him. ‘It’s off-label for this condition, but there’s a lot of anecdotal evidence that it’s helpful for treating it. It might even eliminate your hallucinations with little or no side-effects.’

Sounds great, Doc. What is it?

‘Mifepristone.’

Aka RU-486.

Aka the abortion pill.

Don’t ask me how the pharmaceutical companies figured that one out. Maybe some psychotic depressive was convinced she was pregnant, popped a 486, and suddenly realised not only was she never pregnant but that the father of her child never existed.

However they figured it out, they were right: the abortion pill not only kills babies, it kills imaginary friends as well. I never saw Rachel again.

A year after the accident my mom packed us up and moved to a teaching job at DePaul University. Her friends thought she was running from the memories of her husband, but Mom wasn’t running away from anything. She hated Hollywood life. She was running towards the life she had always wanted. Sometimes we can only be free when the people we love are gone.

One day I came home to our new Chicago house to find Roland in our kitchen. His shirt was a hideous blue-and-orange Hawaiian theme and his goatee had started to sprout grey. Roland had left the studio and moved to Chicago to take a position at the Art Institute. Mom said he wanted to offer help in getting me a job at the museum.

‘We have lots of computers,’ he said to me, like I was some delicate flower.

Mom had told him everything.

‘It’ll be nice to get out of your bedroom, won’t it, honey? Maybe get your own place with all the money you’ll be earning?’

‘Trust me,’ Roland said, ‘you’re going to love the museum.’

I fucking hate the museum and I need to be back there in ten minutes – barely time to finish the paper. Like anyone else, the amount of love I possess for my lunch break is directly proportional to the amount of hate I possess for my job. I cherish this time. But just as I turn to the Celebrity & Lifestyle section he comes in.

The bum.

Besides his torn clothes and his dirt-marked face, he looks like an old version of Ernest Hemingway – or the Gorton’s Fisherman. Silver hair peeks from the bottom of his knit cap, grey whiskers give him a rugged look, but it’s his cool blue eyes that are the most striking.

Every once in a while he’ll burst through the doors screaming about religion or philosophy, before someone offers him coffee to calm him down. I guess the regulars have found it’s quicker than waiting for the Chicago PD to show up. Today he’s unusually frantic.

‘I seek God! I seek God,’ he cries. ‘Where is God?’

This sounds familiar.

‘I will tell you,’ he continues. ‘We have killed him – you and I.’

Ah, Nietzsche.

‘All of us are his murderers.’

Someone give this guy a coffee already.

‘What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives.’

Personally, I think he just pulls this crazy act because he knows you can get a lot more out of people a lot faster by scaring them, annoying them, or making them feel like they’re your saviour, than you can by sitting around asking them for a nickel.

Case in point: a kind-looking, balding man is bringing him a cup of Kenyan Select right now. ‘It’s OK. Calm down. Why don’t you drink this and warm up?’ the coffee-bringer tells the doomsayer. The bum takes it and stands between a set of tables and the snack counter, his body blocking the path of an alternateen barista with pigtails who carries a tray full of biscotti. Her shirt reads: ADMIT IT. YOU’D GO TO JAIL FOR THIS. As the barista awkwardly slips around him, carefully trying to balance all the biscotti on the tray, one falls off. The bum snatches it from the floor before the girl has a chance to see.

Now the bum’s settled into a seat in the middle, at a little round table with a chequerboard. The barista, counting biscotti, eyes him suspiciously. The bum holds his biscotti in both hands, twitching his head left then right, like a skittish squirrel nibbling an acorn.

Choke on it, you freak. My lunch break is almost over and I didn’t even get to finish my paper in peace. I put on my coat and leave the Sun-Times on the table. Someone else will get to finish it. As I walk towards the exit I pass the bum and intentionally check him with my body, knocking him back in his seat. Fuck you, I say in my head.

And just as I get to the door a lady screams.

I turn around and everyone is on their feet. Through their legs a mass of dirt-stained clothes wriggles on the floor. Then a break in the crowd reveals a black knit cap with silver hair sprouting from the back. The bum’s face is turning an ever-darkening shade of blue. He’s grasping at his throat. The motherfucker is choking on his biscotti.

There are eight people between me and the bum, but no one is doing anything. Admit It just rolls her eyes, wearing a face that says, God, this is so inconvenient. I don’t get paid enough to worry about choking homeless people. Some guy near the back has started recording everything with his phone. Look for it on YouTube soon, no doubt.

And maybe the rest of the people don’t know the Heimlich, but I’m betting no one else is helping him because they don’t want to touch a creepy, worthless fuck of a man – worthlessness that might rub off on to them.

I can relate. To the bum, I mean.

Clawing at his throat, he’s a minute closer to death than he was when the lady screamed, and still the crowd is acting like they’re watching a one-man improv show.

And look, I don’t know the Heimlich either, but I did bump him. So I push my way though and kneel at the bum’s side. Then I do the worst thing possible. I do the thing the first-aid refrigerator magnets tell you never to do: I stick my fingers down his throat.

And there’s a reason they tell you that. All I’ve done is lodge the biscotti further down. Panicked, I grab his coffee and pour it into his mouth.

And somewhere in the crowd a woman screams again.

Someone shouts, ‘He’s going to die!’

Someone shouts, ‘His face is so blue!’

Someone shouts, ‘Leave room for cream!’

And, leaning over the nearly dead bum with his mouthful of steaming coffee, I take my middle finger and jam it down his throat.

I thrust up and down, finger-fucking his mouth until the coffee has saturated the biscotti enough to break it in two. As I roll him onto his side the combined coffee and biscotti sludge slowly dribbles out of his mouth and down his whiskered cheek like a mini mudslide. Going back in, I stick all my fingers in his gaping, coffee-scalded mouth, past his rough, rodent-like tongue, till I feel the sewer-slime slickness of his throat and scoop out a clumpy mush of biscotti. I go in one more time, fishing for leftovers.

Then comes the gag.

And his warm, chunky, lava-like vomit flows over my hand.

He gasps for air.

‘I’m not going to go to hell for someone as worthless as you,’ I whisper under my breath, as I watch his sad face lose its blue. His whiskered cheeks softly pump up and down.

‘Oh!’ a woman exclaims. ‘Oh!’

‘Awesome,’ says YouTube guy.

Then I guess the crowd realises they should do something so when they tell this story to their friends they can say they played a part. They help the bum up. They tell him he is so lucky. They tell him to view this as a new day, a new start.

I’m still on the floor, my hand covered with homeless vomit. No one wants to help me up.

My fingers are red and scalded. My heart is racing, beads of sweat dot my face, and it feels good when someone opens the door and the cold April wind blows in.

And when the door bangs shut, she’s on the other side of it again – her raven hair hangs in wet strands before her eyes. Her pale skin is slightly pink from the cold. The place where her ear lobe should be drips with water from the shredded cartilage. And her green eyes stare at me. I mean, right at me. The words from my dream echo in my head: An awakening is needed in the west. Heat radiates from my skin. The little beads of sweat that dot my face evaporate. I’m dizzy and just want to close my eyes, but I can’t look away from the girl. Those penetrating eyes. That mutilated ear.

Then a towel hits me in the face.

‘Here you go, hero,’ the alternateen barista says, moving between me and the door.

I wipe my hand clean of vomit and when I look up again, my dream figment is gone. It rains in her place.

4

Assassins

After you save someone’s life, people don’t just let you leave. When they think you’re a hero, they want to be your best friend. They pretend like they care about you. They pretend to be interested in you because of who you are, not because of what you just did.

I sit on the steps outside the coffee house and let the drizzle fall over me. The barista takes a seat by my side. Her eyes are caked with eyeliner, the raccoon. Inside the coffee house a line has formed at the counter.

‘On my break,’ she says and lights up a cigarette.

I wonder if she’s even old enough to be smoking.

‘That was really cool what you did,’ she says.

But my attention has shifted to across the street. I’m watching the figment from my dream as she stands behind a crowd of Asian tourists who’re snapping pictures of one of the big lion statues that guard the museum’s entrance. But then the Asian tourists, they see a WGN-TV cameraman shooting footage of the museum. It must be for their story on the west wing’s renovation Roland mentioned. So the Asian tourists stop shooting the lion and start shooting the cameraman and a very bored looking reporter.

‘I’m going to be a doctor when I’m older so I can do that stuff every day. Saving lives and shit every five minutes,’ the barista says. ‘What a high.’

‘I don’t think it’s like that,’ I say, thinking of every doctor I’ve ever been to. ‘I think most doctors spend a lot of their time behind desks filling out forms.’

‘I’m talking about being an emergency-room doctor,’ she chides me. ‘They’re always running around saving lives every second.’

‘I really don’t think they are.’ And I think of the night my father died. Across the street my figment is pacing in the rain and holding a flat newspaper under her arm.

‘Don’t you ever watch ER? It’s exactly like that,’ says the all-knowing seventeen-year-old. And I look into her raccoon eyes and consider trying to explain that TV shows only the exciting parts of life; that the boring shit that makes up ninety-nine percent of our existence is edited out. But it would just be a waste of breath.

Across the street my figment seems indecisive. When I look at her she looks away. I’m grateful for that. It’s my mind trying to fight off my hallucinations. Still, it scares me that I’m seeing figments again so often. But it’s my own damn fault. I’ve been so lazy about refilling my 486s. And my shrinks have made it clear: it’s the medicine or shock therapy. And I’m not going to turn out like that. Tomorrow I’ll go to my shrink and get a refill; maybe ask him to up the dose. For now I hail a cab. I tell the driver to take me to my place. I’ve got that one pill I saw buried in my carpet this morning. Donald will just have to believe whatever lie I tell him.

By the time I get back to the museum I’m over two hours late. I couldn’t catch a return cab and had to walk most of the way. I’m freezing. The temperature has really dropped.

I run up the marble steps, hurrying to get out of the cold rain, which stabs like ice picks. Donald’s going to kill me.

‘Museum’s closed, sir,’ a security guard says, blocking my entrance.

Closed? It’s three-fifteen. ‘What do you mean it’s closed?’ I say.

‘It’s closed, sir.’

‘Yes, I heard you,’ I say, showing him my red museum badge. ‘I work here. Why is the museum closed?’

‘This is North Entrance,’ the guard says into his walkie-talkie. ‘I have an employee trying to enter. Yes, sir. Sir.’ He holsters his walkie-talkie. ‘Please wait here.’

Minutes pass and the rain continues to fall before Donald emerges from the emergency exit door. He waves me inside where a museum guard waits with two strange men; one is considerably taller than the other. The strangers don’t have museum badges.

‘It’s OK, we just need to talk,’ Donald says with a coldness that almost crawls from his skin.

The five of us walk in silence down two floors. The construction-lined corridors are practically deserted. The few people we do pass are silent. Some look scared when they see me with the two strangers. And then it hits me: these men are from HR. They’re the guys employees here talk about in whispers. They call them financial assassins because their job is to roam around and find useless employees to lay off. Fewer employees mean more money for the renovation.

We enter a small conference room I’ve never seen before. The museum guard waits outside.

‘Please sit down,’ the tall financial assassin says.

‘Why is the museum closed?’ I say.

‘Where have you been for the past three hours?’ the short financial assassin says. He sounds like he’s trying to channel Magnum, PI.

‘Lunch,’ I say, pretending I didn’t take two hours longer than normal. ‘Donald, what’s going on?’

But ‘Please just answer their questions’ is all Donald offers.

‘Do you normally take a three-hour lunch?’ the tall assassin asks.

Mom will be so disappointed if I lose my job. She was so happy when I took it.

So I say, ‘OK, look, I know I shouldn’t have done it.’

My answer, it causes the two assassins to lean closer and Donald to look a little frightened.

I say, ‘I’m sorry, but you’re not gonna believe what happened.’ And I tell them the events of the past three hours. I lie about the medicine though. They wouldn’t understand. You tell someone you see things and they’ll never look at you in the same way again. Hell, they’ll find a way to fire you just because you’re on psych meds. So instead I tell them that after the coffee house I had to go to my girlfriend’s because she was feeling sick.

To Donald I say, ‘You’ve heard me talk about her before. Harriett?’

But Donald just shakes his head. ‘Why would you leave work for so long to visit a sick friend?’

‘Please,’ the short assassin says. ‘Let us ask the questions.’

‘Girlfriend,’ I say.

Donald looks at me like I’m a liar.

‘Fine, ex. We’re on a break,’ my voice cracks. And I say that my ex-girlfriend, she gets scared when she’s sick. Besides, I needed to wash up. And I shove my hand beneath Donald’s nose so he can smell the dried homeless vomit that’s crusted under my nails.

‘It’s not everyday someone gets to be a hero,’ I say.

‘Can we call your girlfriend to verify all this?’ the tall assassin asks.

‘No,’ I say.

‘Why not?’

‘Because she’s back at work. I dropped her off.’

‘Where does she work?’

‘The Water Tower Plaza.’

‘What store?’

Fuck. I say, ‘Auntie Anne’s.’

‘Auntie Anne’s?’

‘She likes pretzels,’ I say.

And I can tell this isn’t going well, so I take the pity angle. I say, ‘Donald, I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have been so long. It’s been a hard day. Write me up if you want, but please don’t fire me. And please don’t contact my girlfriend. We’re having enough issues as it is, OK?’

And then the outrage angle. ‘Besides, these HR guys don’t have the right to harass her.’

That’s when the assassins look at Donald, who looks back at me.

That’s when he says, ‘These men aren’t from HR. They’re detectives, Jerry.’

Police detectives?

Donald says, ‘They’re police detectives, Jerry. The Van Gogh is missing.’ His steel-grey eyes glaring. It’s the first time I notice that his eyes match the walls of our office.

It takes me a minute to process what Donald has said. The short man folds his arms and keeps his gaze on me. I don’t know what to say. How does a ten-million-dollar painting disappear from one of the most secure museums in the world?

‘You think I took it?’

I sound guiltier than I’d like.

‘You were the last one to see it before it disappeared,’ the tall detective says. ‘You told Donald that you had been in Roland’s studio. You told him right before you went to “lunch”.’

‘That’s not true,’ I say.

Donald eyes me sharply.

‘I mean, it is true that I said that, but I went to look at it with Roland. When I left he was still in the studio with it. He saw it after me.’

The detectives glance at each other.

‘Look, check the fucking security tapes. We’ve got cameras everywhere.’

But then they tell me that for two hours this afternoon all the cameras were non-functional. They tell me this was due to the renovations – some electrical work. Then they ask how long I’ve known the cameras would be inoperable today.

‘I didn’t! I didn’t know about the cameras, I don’t know who stole the Van Gogh, and I wasn’t the last one to see it.’

Then I yell, ‘Talk to Roland, he’ll tell you!’

And the police detective, the short one, he says, ‘We can’t.’

This is where they tell me how they found Roland in his studio. How he had a broken tripod leg shoved through his eye socket into his skull. They tell me how he’s at Rush Memorial undergoing emergency surgery right now.

A moment of mute struggle passes through me. How do you react when you learn someone you’ve worked with, someone your father worked with before you, has been brutally attacked? I try to think of any movies I’ve seen that may give me some clue.

And look, I know this sounds horrible, but I don’t feel anything over Roland’s attack. That’s just how it is. It’s just how I am. But these guys, I can tell they’d expect anyone except the attacker to be all broken up about it – especially someone who’s worked with him for years.

The three of them, they’re waiting for me to react, to show sadness and fear and regret. To show innocence. So I put my face in my hands and soak up the smell of homeless vomit. I flick my tongue between my fingernails and taste the regurgitated-biscotti-stomach-acid mix. My tongue burns. My eyes water.

Then I pull my hands away, ‘Not Roland. Oh my God, please, not Roland.’

And I let the vomit tears flow. I shiver. I shudder. I’m great. Donald even pats me on the shoulder.

‘There, there,’ he comforts mechanically.

I’ll take my Oscar now.

For the next hour the detectives ask me about any bitterness over Roland’s raise. They ask me to repeat my story again and again, looking for inconsistencies; hoping I’ll slip up. At the end I’m so exhausted from answering the same questions over and over, from fake vomit-crying again and again, I can hardly stand. When I do, the tall one puts his hand on my arm. ‘It’s very important you didn’t lie to us about anything just now. It would look bad for you. If you need to make any corrections, now’s the time.’ My thoughts turn to Harriett, but I remain silent. ‘We’ll have follow-up questions in the coming days after we verify your story,’ the detective warns. ‘Don’t take any trips.’

‘Why don’t you go home and get some rest?’ Donald says, as he walks me out. It’s dark now and Michigan Avenue is black and shiny from the cold rain. A cab is waiting. ‘It’s been a hard day for everyone. Try to relax tonight. Go home and watch some TV. And take tomorrow off.’

Before I get into the cab I try to lighten the situation with a joke. But here’s the thing: even though the joke is stupid, Donald, who never smiles at me, lets out a laugh so theatrical I get the impression that he thinks if he didn’t laugh I might hurt him. I also get the feeling that he only walked me out because he wanted to make sure I left.

A dim light shines from the distant downtown skyline through my living-room windows. I walk through the darkness into the kitchen and turn on the ceiling lamp above the table. I run the faucet and scrub the dried vomit from under my fingernails. That’s when I’m surprised to find I’m weeping a little.

Who could put a tripod through Roland’s eye? Why would someone? Then I think, what if they’re some kind of art-museum serial killer and I’m next? And as I’m standing at the sink, scrubbing homeless vomit from beneath my fingernails, I suddenly get the feeling that someone’s watching me.

But pangs of hunger quickly replace my paranoia and I grab some milk and a bowl of Trix and plop down hard on the aluminium kitchen chair.

I should call Mom. I don’t like Roland that much, but he’s been a good friend to her, especially after Dad died. I should call her; tell her he’s in the hospital. I wipe my odd little tears away and take a spoonful of cereal into my mouth. Later. I’ll call her later.

The crunch of the cereal echoes in my skull as I go over everything that’s happened today. The sludge in my head hasn’t left. It still feels like I haven’t slept in weeks. And as I eat, gazing into the darkness of my living room, I still feel someone watching me. And then, with a spoonful of coloured children’s cereal frozen in front of my gaping mouth, I catch two green eyes leering at me from the darkness.

Without taking my eyes off the eyes watching me, I grab a kitchen knife and inch my way into the living room just enough so I can feel around the wall and find the light switch. And that’s when I see it.

The Van Gogh.

And what do you do when you find a stolen painting worth millions sitting on your living-room sofa? You lock the doors first of all, and then you close the blinds. Then you search your house for the person who put it there. Then a thousand thoughts fire through your mind like bullets. How’d it get here? I should call the cops. No, they’ll think I stole it. I should call the museum. No, they’ll think I stole it. I should sell it. No, I need to calm down.

I turn on the TV. I need to relax. No such luck. A reporter is talking about the stolen Van Gogh. She’s on location, in front of the lion statue outside the museum.

On the TV, the reporter says, ‘On loan from an unnamed benefactor…’

She says, ‘Estimated value: over ten million…’

She says, ‘Employee attacked in his studio…’

I am in so much trouble.

Then on the TV, the reporter says, ‘Sources close to the case have just informed us that they may have a lead.’

And this is where I expect the reporter to tell me to wait just where I am. The police will be right over. Finish your Trix.

‘Police are saying that they have questioned and released – for the time being – a “person of interest” in the case,’ the reporter is saying. Then the image on the screen cuts to footage of the museum from this afternoon. You see a man with his fat wife and plump little Mexican children. They’re standing in front of one of the big, green lion statues outside the museum. ‘We shot this footage today for a story about the fifty-million-dollar renovation of the museum’s west wing,’ the reporter says. ‘It’s now thought that this was around the time the theft occurred.’

And on the TV, the Mexican family has walked out of frame and now we see a group of Asian tourists with cameras around their necks. And behind them…

‘We’ve learned that, due to electrical work on the renovation, the security cameras were apparently disabled for an unknown amount of time this afternoon,’ the reporter says. ‘Authorities aren’t yet sure if the thief knew of the lapse in security.’

Behind the Asian tourists stands a woman.

A woman with skin like cream.

And hair as dark as a raven’s folded wing.

A woman with a mutilated ear.

The footage on the television, it shows the woman, the one from my dream. The one in the silverware factory. The hallucination at the coffee shop. The one who’s nothing more than another figment of my imagination.

But it can’t be.

Figments can’t appear on film.

5

Occam’s Razor

I covered the Van Gogh with a sheet and haven’t looked at it since. Then I watched the news all night to see if there was any new information. And to see if they would play the footage again in which I saw my figment. But no subsequent story ever showed the same footage. Even if one had I’m sure she wouldn’t have been there again. Once you’ve stolen a Van Gogh and you start seeing your imaginary friends on TV it’s easy enough to connect the dots: I’m going crazy because I’ve come off my meds and now I’ve put someone in the hospital.

At seven this morning I stole my neighbour’s Tribune from across the hall. The headline on the front page read ‘MAYHEM IN THE MUSEUM!’ Words from the article jumped out: ‘PHOTOGRAPHER’, ‘CRITICAL CONDITION’, ‘CO-WORKER’, ‘PERSON OF INTEREST’, ‘STOLEN VAN GOGH.’

I threw it back into the hall.

At nine I called my shrink’s office and got an appointment for three.

‘I think I’m sick again,’ I tell my shrink, before I’ve even sat down. I say I think my figments are coming back.

‘Slow down, Jerry,’ he says. ‘What do you mean?’

And I suddenly wonder if my shrink watches the news. I wonder, how far does doctor-patient confidentiality go? So I lie and say that I was at the video store at lunch yesterday. I wanted to buy a DVD, only I had forgotten my wallet. When I left the store I saw one of my figments across the street. Then, when I got home that night, I discovered the DVD sitting on my couch.

I ask him if it’s possible that my psychotic depression is getting worse. That instead of just seeing people who aren’t there, is it possible that I am becoming them? Is it possible I have some kind of split personality and unconsciously carry out actions under their persona? Is it possible to do all this and not remember?

‘Which of your figments did you see?’

I say, ‘A new one. Not Rachel.’

‘One you haven’t seen before you were on the mifepristone?’

I nod.

‘And when did you start to see this figment?’

‘Several weeks ago,’ I remember. ‘Only I didn’t realise she wasn’t real. I saw her once on the sidewalk in front of the museum. Then sitting in the garden at the side of the museum. I thought it was coincidence when I noticed her in a few different places, but then I remembered that I dreamt about her years ago. That’s when I realised I had gone off my meds. I knew I should have come for a refill sooner, but I kept putting it off. I thought she’d go away. But then I saw her at lunch and she felt more real than ever. And now the DVD…’

‘Continue, continue,’ he says.

I originally went to this shrink when we moved to Chicago because my shrink in LA recommended him. But for my tastes he’s too talky. My old shrink would just prescribe medicine and be done with it. This shrink loves to hear about my feelings.

So I tell him how I’ve started dreaming this old dream about her. How in the dream she’s terrified; how she fights off intruders.

My shrink listens and then says, ‘Last time we spoke, a few months ago, you had just been turned down for a raise, am I right? This would be around the same time you started seeing this figment, correct?’

‘Yeah,’ I say. ‘Maybe three weeks later.’

‘Right … two months ago was early February,’ he says, watching me closely. ‘Three weeks after that – well, Jerry, that’s around Emma’s birthday, isn’t it?’

‘March second.’ I look away.

‘You ever heard of Occam’s razor, Jerry? It says that, all other things being equal, the simplest explanation tends to be the right one. Now, what’s more believable? That you are suddenly suffering from split personality disorder and secretly stealing DVDs? Or that, because of the stress of rejection from not getting your promotion, the fact that you’ve gone off your meds, and the relatively close timing to your sister’s birthday, your brain has had a relapse and started giving you nightmares and making you see a figment again? You know stress aggravates your condition. And as for this figment, this dream – is she like Rachel? Have you ever thought you touched her, talked to her, had sex with her?’

No, doctor.

‘Our minds play tricks on us all the time,’ he says. ‘You know this more than most. I mean, Jerry, I buy things all the time and forget I’ve bought them.’

I didn’t buy a ten-million-dollar painting and forget about it, I want to say.

‘You’ve never talked much about your sister’s death, but I think you should seriously consider how it’s affected you.’

‘I’m fine.’

‘Fine, Jerry,’ he says with a pause. ‘The dream. Let’s go to the dream. The girl in your dream is around Emma’s age when she passed, right? This girl is scared as faceless invaders attack her, while you lie in the background, naked and helpless. Jerry, it seems like you’re visualising what you felt like when Emma’s leukaemia invaded her body.’

And I squirm.

‘Though you were present, there was nothing you could do.’

Yes, I could have.

‘You were in effect – as in your dream – naked and helpless. You were only a child. Are you hearing me? There wasn’t anything you could have done.’

But I could have.

My eyes feel swollen. ‘Could you up my dosage, Doc? Could you, just for a little while? Just until this thing passes? I got lazy. It was my fault. I got off the meds and I think I really need a top-up to get me back on track.’

‘I really think the best thing for you,’ he says, ‘is to get out of your box. A little trip can do a lot of good. The world is a wonderful and amazing place. Go see some of it. Take a vacation. What about Heather? You two still seeing each other?’

‘Yeah. Yeah, I’m seeing Heather tomorrow,’ I say. ‘Doc, I’ll look into a vacation, I promise. But, in the meantime, could you just up my dosage a little? Please?’