Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

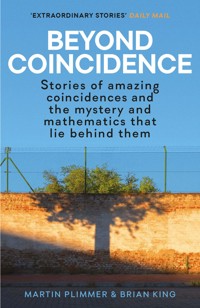

UPDATED EDITION WITH OVER FIFTY NEW STORIES 'A FIRST-RATE BOOK' - THE OBSERVER Laura Buxton, aged ten, releases a balloon from her garden. It lands 140 miles away in the garden of another Laura Buxton, aged ten. Coincidence? Or something beyond coincidence? Is someone playing snap with our lives? Could it be the hand of God? Or are we, as some scientists have suggested, being granted an insight into a hyper-connected universe whose ubiquitous web-like workings we can only dimly discern? Beyond Coincidence is a celebration of the universe's most beguiling phenomenon, containing more than 250 amazing stories of coincidence. From sympathetic magic to the science of probability, from the vicissitudes of gamblers to the mysterious communions of subatomic particles, this book chases coincidence in all its many guises, analysing how it affects every aspect of our lives and why it means so much to even the most sceptical of us.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 434

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for the first edition

‘Extraordinary stories’ Daily Mail

‘An intriguing investigation of the cosmos’s most improbable events … a first-rate book’ Observer

‘An entertaining and intelligent study’ Mail on Sunday

‘Pretty amazing’ Simon Hoggart, Guardian

‘Fascinating’ The People

‘Beyond Coincidence has already resulted in many an overlong stay in the toilet’ David Baddiel

‘Hundreds of great stories to keep you entertained’ Focus

‘Addictive’ Midweek

‘A cornucopia of coincidence brimming with more than 200 case histories … a superbly-crafted compilation of the most celebrated examples of the genre … a marvellous “greatest hits” album’ Worchester Evening News

‘Addictive’ The List

‘Book of the Month’ ***** Maxim

‘Absorbing’ Ink

‘An intriguing book containing more than 200 stories of coincidence’ Radio Times

‘Fascinating’ Fate & Fortune

‘Guaranteed to send a shiver down your spine’ Good Book Guide

‘Amazing’ The Lady

To the memory of Peter Rodford who, coincidentally, taught us both.

Acknowledgements

We are not the first to follow the coincidence trail – and we won’t be the last.

Thanks to all who went before us and whose bright tracks we came across as we trawled the universe of infinite possibility. Thanks in particular to coincidence super-sleuths, authors Ken Anderson and Alan Vaughan, and to the Library Angel, who visited us just as she visited them.

Thanks also to mathematician Ian Stewart, psychologists Chris French and Richard Wiseman, author John Walsh, comedian Arnold Brown, cabaret duo Kit and the Widow, ‘psychic’ Craig Hamilton-Parker, biologist Rupert Sheldrake, research scientist Pat Harris, mountaineer Christina Richards and solicitor David Barron. Thanks to our saintly agent, Louise Greenberg and eagle-eyed editor, Ruth Nelson.

Thanks to all who have been astute enough to spot when their personal universe folded in on itself and who recorded the details for posterity, and to Sue Carpenter for collecting and giving us access to many of their accounts.

Special thanks to Nick Baker at Testbed Productions, through whom we made the original Radio 4 series Beyond Coincidence, which inspired this book.

And finally thanks to the two Laura Buxtons, whose balloon pops in the face of those who deny that coincidence, whatever its meaning, or lack of meaning, is charming, spooky, mischievous and endlessly entertaining.

‘Any coincidence’, said Miss Marple to herself, ‘is always worth noting. You can throw it away later if it is only a coincidence.’

Agatha Christie

Contents

Introduction

Since our book first appeared, extraordinary coincidences have continued to occur on a regular basis, surprising, delighting and mystifying us in equal measure.

If some strange unifying force is behind such things, then clearly its power is undiminished. The insistence of mathematicians that coincidences are no more than simple manifestations of the laws of probability carries little weight with those who find themselves at the heart of remarkable chance events, such as the two men involved in this recent, widely reported story:

US state trooper Michael Patterson was on patrol in New Jersey in the summer of 2018 when he pulled over the driver of a white BMW for a minor traffic offence.

The motorist, Mathew Bailly, was a retired police officer and as the two men chatted, Patterson mentioned that he’d grown up in a street called Poe Place. Bailly said he remembered Poe Place well, because he’d helped deliver a baby in a house there as a rookie, 27 years earlier.

It didn’t take much detective work for 27-year-old Patterson to put two and two together. His mother had often told the story of the day she’d gone into labour; how her husband had called 911 in a panic and a police officer had turned up to help.

‘Yes,’ said Patterson. ‘I was that baby. Thank you for delivering me.’

It’s a delicious story, and marvellous that the two men were reunited in such a neat way. Was this just coincidence, or was some cosmic force at play? The odds against such a chance occurrence are clearly not astronomic, but certainly the two men involved felt that something pretty special had happened.

Recent studies into the science and psychology surrounding coincidences have produced fascinating new insights into why seemingly inexplicable events occur and, more importantly, how they influence human behaviour.

For example, cognitive psychology experiments reveal that in a straight competition between rats and humans set the task of responding correctly to a series of random, coincidental events, rats are almost certain to come out on top.

You can try this at home. Invite some friends round and an equal number of rats, then bombard them with a sequence of green and red lights. Set things so that 80 per cent of the lights are green and 20 per cent are red, but fire them off randomly. Invite all participants to predict the colour of the next occurring light. You will find that the rats will instantly recognise that there are more green lights, and consistently and correctly choose green as the next most likely colour (though they’ll need a reward for a right answer to induce them to play along). Your human friends will notice the preponderance of green lights too, but will be distracted by an irresistible temptation to identify ‘patterns’, which will lead them to believe red will appear more frequently than is actually likely. Your friends’ success rate will be diminished. The rats will win … and inherit the earth.

Psychologists examining our persistent failure to grasp the concept of randomness have identified a strong human tendency to search for and find patterns within sequences of events. They call it the ‘clustering illusion’. Gamblers, or at least bad gamblers, will see patterns in a run of cards being dealt, in the toss of a coin, the spin of a wheel or in the form of racehorses. They’ll analyse those patterns, find sequences and arrive, very often, at costly wrong conclusions. They will have failed to understand that any pattern observable in a sequence of random events only tells you something about the past. It does not predict the future.

This predilection for pattern exists in all of us, not just gamblers. It’s to do with the way our brains have evolved to deal with complex environments. The downside is that it creates a potential for miscalculation which rats successfully avoid. It should be conceded, however, that a rat has never broken the bank at Monte Carlo.

Conspiracy theorists are also fond of playing fast and loose with the laws of probability.

According to political scientist Professor Michael Barkun, conspiracy theories are built on the conviction that the universe is governed by design. They embody three principles – that nothing happens by accident, nothing is as it seems, and everything is connected. In other words, in the mind of the conspiracy theorist, there is no such thing as coincidence.

Such thinking has led to worryingly large numbers of people becoming convinced that the Apollo Moon landing was faked, that John F. Kennedy was assassinated by the CIA, or that the royal family was behind the death of Princess Diana. More recently, it was vociferously asserted that the 2012 massacre of 26 people at the Sandy Hook elementary school in Connecticut was a hoax, perpetrated by left-wing gun control lobbyists. It was all done with actors apparently.

We have a compelling need to understand the meaning of life, the universe and everything. But when the most obvious explanations for unsettling events don’t suit us, we reach for ‘alternative facts’. Which brings us neatly to the President of the United States of America.

Putting aside the possibility that the election to the highest office of the billionaire reality television star was itself a hoax, perhaps we should sympathise with poor Donald Trump, who has found himself at the centre of a flurry of conspiracy theories. Many of these were built on apparent coincidences linking him with Russian interference in the presidential election process. Eagle-eyed journalists and political opponents identified various interactions between people working for Donald Trump and associates of Russian President Vladimir Putin, not least a famous meeting at Trump Tower between Donald Trump Jr, Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner and a number of Russian operatives. All parties involved denied that any ‘dirt on Hillary’ was exchanged.

On 27 July, 2018, global attention focused on a photograph of Robert Mueller, the former CIA director investigating alleged collusion between Trump and the Russians, sitting reading a newspaper at the Reagan National Airport, while, standing just feet behind him was Donald Trump Jr, surrounded by secret servicemen. In the absence of any evidence that either man was even aware of the other’s presence, conjecture was still rife that this was something more than mere coincidence.

In any event, it definitely feels like a good time to return to our study of the mystery and mathematics of coincidence, to update our book and introduce lots of intriguing new coincidence stories.

Coincidence stories are not hard to find. As we were working on this revised edition of Beyond Coincidence, this headline popped up on the BBC News webpage:

SOMERSET LOST GOLD RING FOUND ON CARROT DUG UP FOR DINNER

The ring, with an amethyst stone at the centre, had been bought some 30 years earlier by Dave Keitch as a birthday gift for his wife Lin. It had been missing without trace for twelve years.

In August 2018, Dave dug up some carrots in their back garden and left them for Lin to prepare for their evening meal. As she began to scrub off the mud, she was astonished to discover her ring, clamped around the tapered end of one of the carrots. To Lin it looked like the carrot was wearing her ring.

Such things certainly don’t happen every day. It was ‘a chance in a million’ according to Lin Keitch, though she is not a mathematician. Having said that, a mathematician might well come up with a similar figure, but would definitely also point out that such odds are not actually particularly long. The chance of someone winning the National Lottery is around 14 million to one, but people win pretty much every week. Now if Lin had won the lottery on the same day that a carrot turned up wearing her ring, we’d be looking at considerably longer odds and perhaps speculating that mysterious forces were at work. Though equally improbable things do happen, as we’ll see.

Since we first wrote about coincidence there has been an enormous increase in the use of social media. With its infinite capacity to connect people, this technological phenomenon substantially increases the likelihood of chance conjunctions being noticed and talked about. But in another way, social media can kill a coincidence story stone dead, as in this case:

Gary Crossan’s wedding ring slipped off his finger while he was out swimming in the chilly Atlantic waters at Portsalon in County Donegal. He never expected to see it again.

Three weeks later Ann Busch and her three young daughters were making sandcastles on the beach when they found a ring engraved with the name Maria, and a date.

They posted details on Facebook, where it was quickly shared thousands of times. A surprisingly large number of people quickly responded to say they had lost rings at Portsalon, but none turned out to be its rightful owner. But then, tipped off by his brother-in-law, who had spotted the Facebook post, Gary identified the ring as belonging to him, engraved with the name of his wife, Maria.

Another nice story, but the intervention of social media effectively prevented it from becoming a great coincidence story of the type which liberally decorate the pages of this book. Before the days of social media, Ann Busch would not have been able to locate the ring’s owner. She might well have given it to her daughter who would have treasured it until she grew up and, by a wonderful twist of fate, become engaged to Gary and Maria Crossan’s son. Only then would the extraordinary coincidence emerge, probably on their wedding day.

The odds against such a sequence of events actually happening would be very long, but as we explore in this book, the ‘law of truly large numbers’ explains how such things are not just possible, but almost inevitable.

So fear not, coincidences are not an endangered species. Social media is not that powerful.

Sir David Spiegelhalter is the Winton Professor for Public Understanding of Risk at the University of Cambridge. As part of his research he set up a coincidence website, inviting people to submit their experiences. At last count there were nearly 5,000 stories which have been broken down into categories – sharing a birthday with someone (11 per cent), meeting people while in transit (6 per cent), coincidences relating to marriage and in-laws (5.3 per cent) etc. Sir David is a statistician.

As a man of science, Sir David is naturally sceptical of any mysterious explanations behind or beyond coincidences. He argues that unlikely things happen very frequently. As he put it in a Guardian article:

‘Christmas brings round-robins and the predictable tales of other people’s brilliant children and exciting winter holidays in the sun. This is perhaps only matched by the dullness of hearing about the coincidences they have experienced – they met their next-door neighbour in Azerbaijan, they cracked open an egg in Cambodia and there was the wedding ring they lost ten years ago, etc. Yawn.’

But in an interview broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in March 2018 Sir David told the story of a man who was on holiday in Italy and came upon a group of men having a party at a winery. It transpired that the men had formed a club because they were all born on the same day, 27 January 1953. By coincidence this was also the holidaymaker’s birthday, so he was immediately invited to join the celebrations.

At which point in the telling of the story the programme’s producer, Kate Bissell, interrupted proceedings to point out that 27 January was her birthday and, even more extraordinarily, it was also the birthday of the recording engineer. Admitting to being delighted to be part of an astonishing unfolding coincidence story, Sir David calculated that the odds of such chance events coming together were … very long indeed.

What are we to make of such things? Is it mystery or mathematics?

Read on and decide.

PART 1

Coincidence under the microscope

Chapter 1

The cosmic YES!

I know we’ve met before.

Let’s talk. I’m sure we’ll find things in common – broad strokes first: language, race, nationality, gender, front door colour, love of Italian food, the desire to jump in puddles … this book!

Soon we’ll narrow the focus: places we have both visited, times we have nearly met, events at which we were separated only by people we didn’t know, people we know in common …

The more we look the more we’ll find. Before long we’ll discover we have lived in the same town, or attended the same school, were born in the same hospital, had the same accountant, the identical dream … Perhaps we travelled on a London bus together – perhaps we have rubbed shoulders on a bus!

The idea makes us shiver. Why? Does it mean anything? Not objectively. After all, we rub shoulders with strangers on buses every week and it doesn’t make us shiver.

But now we are no longer strangers. And now, knowing each other, we can see that we have always known each other. If, after this meeting, we become friends, we will think those former meetings and almost meetings very significant indeed. We will call them coincidences, but we will think them more than that. The trick of being personal is in the nature of coincidence. It is always particular, always subjective, always to do with us. Fate has singled us out. You and me. It’s that specialness which makes us shiver.

We all do this, especially if we want to like each other. We frisk each other for links. We’re like synchronised swimmers in search of a routine. We relish connections, and we’re a highly connected species. If it were possible to map all human activity, drawing lines between friends and relatives, departures and arrivals, messages sent and received, desires and objects, you would soon have a planet-sized tangle of lines, growing ever denser, with trillions of intersections.

Each intersection is an association waiting to be noticed as a coincidence, either for its own sake or when yet another intersecting line passes through it. Coincidence is commonplace. It’s everywhere. But we are only aware of those intersections that are meaningful to us. Paul Kammerer, an Austrian biologist of the early 20th century, said that these are manifestations of a much larger cosmic unity, a force as powerful as gravity, but which acts selectively, bringing things together by affinity. We only notice its peaks, which are like the ripples on the surface of a pond.

Just what this force affecting us all might be, we don’t know. Suggestions include a higher universal intelligence, gods and aliens (both mischievous and benign), a psychomagnetic field, the controlling power of our own thoughts, or a universal system of parallel universes operating in different dimensions from ours. That’s easy to say, hard to understand and impossible to prove.

Back on the ground, all that most of us are aware of when we notice a coincidence is that it provokes one of those shivers. It might be just a tremor of the imagination, but the more unlikely the coincidence, the more the sensation of invisible fingers running down the back.

Bolt-from-the-blue coincidences involving events or material objects – like bumping into a long-lost friend in a foreign town, or finding a toy in a jumble sale that you once owned as a child – can move even the most sceptical in ways that are difficult to define.

What is it about coincidences that grabs at the emotions? It’s the frisson of being touched by something outside of yourself. It’s a sense of being chosen. One minute you are stumbling through quotidian chaos, trying to find a phone that is ringing or manoeuvre a pushchair up the stairs of a bus, the next you are in a lacuna of clarity, where every disparate thing – events, objects, your own thought processes – appears to be bent to the same end. For a second the suspicion that you are tiny and insignificant, and the universe arbitrary and terrifying, disappears. You are part of a great cosmic YES!!!

Research has been done suggesting that people who are most alert to coincidences tend to be more confident and at ease with life. Every coincidence they experience – even the minor ones – confirms their optimism. They know that things will happen to them, that somewhere in a second-hand Guadalupe bookshop there is likely to be the one remaining signed copy of their father’s only novel, that in an apartment in Hong Kong, waiting to be found, very likely lives the sister they have not been told about, that the signet ring they lost in Holland is sitting right now on the bottom of the Zuyder Zee awaiting the astonished angler’s casual hook. They are routinely alert to coincidence, certain that at any moment, in the raffle of infinite possibilities, their lucky number will be called. For these people the world really is a smaller place.

Let’s think about that book in Guadalupe for a second. Let’s say it was written by my father. If you came across it as you were browsing books, you wouldn’t think anything of it; after all, rare bookshops are full of rare books – it’s in their nature. But if I were to find that book, open it and recognise the signature of my late father, carelessly scrawled there when he was a younger man than me, with the world and all its manifold possibilities lying at his feet, the experience would be loaded with poignant significance. Just what it signified exactly, I would be hard pressed to explain, nevertheless my world would look very different from what it had looked like a few moments before. I might even have to sit down.

Laurens van der Post says in his book, Jung and the Story of Our Time (about Carl Jung, the Swiss psychologist who defined the concept of synchronicity): ‘Coincidences, instinctively, have never been idle for me, but as meaningful, I was to find, as they were to Jung. I had always had a hunch that coincidences were a manifestation of a law of life of which we are inadequately aware … [Coincidences], in terms of our short life, are unfortunately incapable of total definition, and yet, however partial the meaning we can extract from them, we ignore them at our peril.’

When coincidences resonate personally and intimately it becomes hard to dismiss them as mere chance, events slung together by the wind. That was certainly how the person at the centre of this following story felt.

US serviceman Dylan was relieved when his posting in Kirkuk in Iraq came to an end. The tour had been hell on earth, with the constant threat of attack by suicide bombers. The one saving grace had been the friendship he had struck up with a local youngster called Brahim who was working as a janitor at the military base. Brahim reminded Dylan of his younger brother Rory back in California. As Dylan was waiting to be airlifted out, Brahim came up to say goodbye and to tell him he’d been given a job as translator. Dylan flew out, worrying that Brahim was risking his life working for the occupying military force.

It was several years later, after Dylan had left the US air force, that he got the terrible news that his brother Rory had been murdered in a carjacking incident near their family home. Dylan couldn’t believe that he had survived Iraq and his brother had died in the safest place he knew. He was devastated.

Heading home for the funeral, Dylan first flew to Arizona to collect some personal items. At the airport he jumped into a taxi. The driver struck up a conversation, explaining that he was from Iraq … from Kirkuk.

The driver turned round. His voice was deeper, he was a foot taller, but it was Brahim. They were both overwhelmed to have found each other again. Dylan felt that he had lost one brother, but found another.

Recalling the events in a radio interview in 2018, Dylan said: ‘I’m not a spiritual or religious person; I’ve seen too many bad things to believe in a higher power, but it seems like the universe put Brahim there at this worst time in my life. That moment probably saved my life. It helped me immensely. It gave me hope.’

Dylan’s experience may or may not have had a deeper meaning in any truly objective sense, but it was meaningful to him.

Here’s another curious fact: the coincidence is meaningful to the reader as well. The reason we respond positively to accounts of coincidence, ever eager to give them the benefit of the doubt, is because they make such good stories. They have the resonance of myth and fairy tale, with their dramatic shifts of fortune, their spectacular life and death events and their many enchanted objects and preoccupations: crossword clues, rings, keys, addresses, numbers and dates. There is a ritualistic quality to them because of their complex storylines: the histories, character traits, dream and thought processes which have to be established and explained in the correct sequence before the coincidence climax can be appreciated. A good coincidence story has the gravitas of Greek drama, the difference being that it is true.

We, the authors of this book, have been acutely aware of this quality while writing it. So we have not stinted on stories. There are over 200 in Part 2 and others scattered liberally through the book. Some are old classics that wouldn’t let us leave them out (and which, like myths, thrive on the retelling); many are told here for the first time.

Carl Jung called coincidences ‘acts of creation in time’. The sheer potency of the stories, and the emotional catharses and transformations they wrought in some of their subjects, testify to that.

All writers have a working arrangement with coincidence. Few novelists are too proud to insert a dramatic coincidence in order to tart up a lacklustre plot. Without coincidence comedy routines would be deadly serious. Allegory and metaphor work by linking together two normally unconnected ideas in order to startle the reader into seeing something they thought they knew in a different light. When poet Stephen Spender describes electricity pylons crossing a valley as ‘bare like nude, giant girls that have no secrets’ he is utilising the visual energy of something entirely unrelated to pylons in order to shock the reader into a sense of blatant and gauche vulgarity. Metaphors aren’t coincidences, as they are man-made, but they work the same trick: fusing unrelated entities to power a revelation.

An interviewer once asked the writer Isaac Bashevis Singer how he could possibly work in such an untidy study. The interviewer had never seen such a cramped and confusing place. Every ledge in the room was taken up with teetering stacks of paper and books piled up on top of each other. It was perfect, said Singer. Whenever he needed inspiration a pile of papers would fall off a shelf and something would float to the floor that would give him an idea.

There is one kind of coincidence for which all writers have a healthy respect. It manifests itself when you are researching a subject and relevant facts appear everywhere you look. Carl Jung called it the Library Angel and grateful writers leave offerings to it by their bookshelves at night.

When Martin Plimmer was researching the first edition of this book, he started looking for information about neutrinos – particles so small scientists have never seen them. He was interested in ways we might connect, not just with each other, but also with the physical world and the universe beyond. Neutrinos, which originate in stars and shower the Earth constantly, seemed to suggest a medium for universal intimacy, as they pass right through us, and then through the Earth beneath us, without stopping for the lights, flitting through the empty space in atoms as though there were nothing there. Martin had never heard of neutrinos, but pretty soon the air was thick with them.

He opened a newspaper at random and there was a story about neutrino research. A novel he was reading offered an interesting neutrino theory. When he turned on the television, there was former president Bill Clinton talking about them in a speech. When he looked down at his fingertip, a billion of them were passing through it every second. Funny how he’d never noticed them before. It was as though the whole world had gone neutrino flavour.

Again, you could say that all this stuff is always out there waiting to be noticed, part of the barrage of information which passes before our overloaded senses every day. Our attention is selective; we see only what preoccupies us at the time. That week neutrinos were big, so neutrinos were everywhere. The world appeared to be bent to Martin’s current obsession, and the search engine of the gods was suggesting ideas, links and information.

None of this theory about the barrage effect of information applied to novelist and historian Dame Rebecca West when she was searching for a single entry in the transcripts of the Nuremberg trials. She had gone to the library of the Royal Institute of International Affairs for the purpose and was horrified to discover hundreds of volumes of material. Worse, they were not indexed in a way that enabled her to look up her item. After hours leafing through them in vain, she explained her desperation to a passing librarian.

‘I can’t find it’, she said. ‘There’s no clue.’ In exasperation she pulled a volume down from the shelf. ‘It could be in any of these.’ She opened the book and there was the passage she needed.

It would be nice to think that something less fickle than chance was at work here. Did the item want to be found? Did her mind, with the right concentration of psychic energy, ‘read’ which volume it was in? Or did the Library Angel lend her a helping hand? Whatever helped her, it distributes its blessings impartially: for Rebecca West, a session transcript out of thousands from a trial of mass murderers; for a devout Muslim fisherman in Zanzibar eager for evidence of God’s greatness, a fish with the old Arabic words ‘There is no God but Allah’ discernible in the patterning on its tail.

If coincidences cluster around preoccupations, imagine how they fall over to please you when the subject is coincidence itself. This book’s origins lie in a five-part radio series, Beyond Coincidence, made by Testbed Productions for BBC Radio 4. No sooner had we started our research than so many coincidences happened around us that we began to feel like we were being stalked. Newspapers fell open at accounts of coincidences, potential contributors, at the moment we rang them, were interrupted in the act of writing about coincidence (or so they told us, but then they were in the coincidence business too).

On the way back from Portsmouth one day after interviewing a woman who was doing psychic research, we pulled off the road to lunch in a pub. Suddenly Martin began talking about the design of a car he had seen in London. This was unusual because, uniquely among men, Martin is not interested in cars. Normally he can’t differentiate one model from another; he can barely remember the make of his own. This time he’d been so struck by the car he’d made a mental note of the make. It was an Audi.

‘And if you could afford to buy one of those cars,’ said Brian, ‘would you like to own one?’

‘Well, yes’, said Martin, considering a novel idea. ‘I think I would.’

‘Then I know just the place you should go,’ said Brian, and he pointed through the window behind Martin’s back. Across the road opposite the pub was a car showroom called Martin’s Audis.

Later Martin and Brian were recording random interviews in the street, asking people about their experiences of coincidence. The sixth person stopped revealed he had devoted his life to recording coincidences. His home, he said, was a shrine to synchronicity. By this time it did not seem odd at all. Coincidences? We could call them up at will! Perhaps what we should have been doing was concentrating our powers on winning the lottery.

So far so benign. We’ve tended to think of coincidences as having good intentions, though as neither random events nor the actions of gods (depending on your standpoint) are necessarily friendly, there’s no reason why they should be so restricted. Of course, unhappy coincidences happen all the time.

If a woman were to urinate in your suitcase because it resembled her unfaithful husband’s (you snigger, but it has happened), you would feel as though you were trapped in a real-life Brian Rix farce.

And if you were the one person among a crowd of spectators to be hit in the eye by an errant cricket ball you would consider yourself very unlucky, especially if, just as you thought it might be possible to get over it, you were hit again. Like all the most interesting coincidence stories this sounds invented, but it didn’t feel that way to Paddy Gardner, watching Andrew Symonds batting for Gloucestershire against Sussex in June 1995 (he took her flowers afterwards). Paddy must have felt like the victim of a malicious cosmic trick, though at least she had a good story to tell.

If all the passengers on a 747 jumbo jet happened to pack a small anvil in their hand luggage, the effect wouldn’t be beneficial to any of them and they probably wouldn’t be able to tell the story either, though the rest of us would be fascinated to read about it in a newspaper, or a novel, or watch it take place in a film. The pattern of coincidence engages us, even when it involves hardship or tragedy, and even victims of bad coincidence may experience a compensating sense of being included or chosen. Sometimes it is better to be noticed, even if we suffer by it, than to be ignored.

We have included lucky stories and unlucky stories in this book, funny stories, sad stories, violent and romantic stories. We love coincidence so much that a misguided assumption prevails, that if a story contains one then it is, by definition, interesting. Many coincidence books have been written with that lazy principle in mind. It may be true, but apart from revisiting a few classic stories such as the Titanic prediction and the Lincoln and Kennedy similarities (shiver) we’ve worked hard to find stories that are interesting in their own right. We threw away a lot of stories that went: ‘I travelled to Thailand for my summer holiday and I met a woman who used to go to school with my brother in Anglesey!’ On the other hand if we’ve left the odd one in, it’s because the woman wore purple lipstick or knew how to wolf whistle.

Enjoy the book. You should, as we share an interest in coincidences. Maybe we’ll bang into each other again one day.

But then again, realistically speaking, maybe we won’t, because, despite all the shivering, we have to be realistic, otherwise we’d sit at home all day waiting for lucky gold bars to fall out of badly loaded airborne Securicor planes onto our lawn. It’s all very well being one with the great cosmic YES! But everyday life has to go on. As comedian Arnold Brown says: ‘It’s a small world, but you wouldn’t want to paint it.’

Chapter 2

Why we love coincidence

Mrs Willard Lovell locked herself out of her house in Berkeley, California. She had spent ten minutes trying to find a way back in when the postman arrived with a letter for her. In the letter was a key to her front door. It had been sent by her brother, Watson Wyman, who had stayed with her recently and taken the spare key home with him to Seattle, Washington.

Most of us have locked ourselves out of our houses at some time or other. Some of us will have received a key through the post in a letter. Very few of us will have had both experiences synchronised so exquisitely. How would you feel if that happened to you? There you are, trying to cope with an unwelcome and vexing predicament when suddenly, like magic, the solution is handed over on a plate, or in this case, in a letter. You’d feel pretty special probably.

Coincidences can be deliciously ironic. Back in 2004, the Director of the BBC Proms, Nicholas Kenyon was invited onto BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme to respond to conductor Sir Simon Rattle’s decision to restart a concert because it had been disrupted by a member of the audience’s mobile phone. Launching into a mild rant about the failure of audience members to switch off their phones, the interview was itself interrupted – by the merry ringtone of Nicholas Kenyon’s own mobile phone.

All the world loves a coincidence. We are attracted to their pattern and order – their symmetry. We can even become addicted to them. The more remarkable the coincidence, the more we savour it.

And the more remarkable the coincidence, the more the tendency to believe it must have some sort of deeper meaning or significance; to see some sort of benign, God-like hand at work, offering a moment of relief from the general randomness and disorder of our everyday lives.

For many people these very personal experiences of coincidence can border on the religious. A major survey conducted in the United States in 1990 asked people to describe spiritual or religious-like experiences they had had. A large majority cited ‘extraordinary coincidences’.

In his book Synchrodestiny, alternative-medicine guru Dr Deepak Chopra, offers advice on how to ‘harness the infinite power of coincidence to create miracles’. He details how ‘through understanding the forces that shape coincidences, you can learn to live at a deeper level and access the flow of synchronicity that lies at the heart of existence.’ Less mystically, psychologist Stephen Hladkyj spent several years studying coincidences experienced by students at the University of Manitoba. He found that first-year students at the university who were highly alert to synchronicity (meaningful coincidences) in their lives, also scored higher on a self-rated measure of psychological health and generally adapted well to their first year of college life.

He concluded that people who are alert to coincidence – particularly personal coincidence – tend to see the universe as a friendly, orderly, responsive place, and consequently develop a general sense of well-being. Coincidence, it seems, is good for us.

It is somehow deeply comforting to know that a balloon released from a garden by ten-year-old Laura Buxton landed 140 miles away in the garden of another girl, also called Laura Buxton, also aged ten. In the case of such a delicious coincidence as this, it feels almost sacrilegious to start analysing the statistical likelihood of such an event occurring. It just did. And the world seems a better place for it.

Distant observers, from another planet perhaps, might not see any particular significance in the story of the two Laura Buxtons. A child releases a balloon. Sometime later it comes down in a garden somewhere else and is picked up by another child. Nothing exceptional there. Children are attracted to balloons after all, and balloons do go up and come down again. The children are the same age and have the same name. So what? But here, on Earth, this sequence of events looks rather special. Certainly special enough for the authors of this book to invite the two Laura Buxtons to the party to celebrate its first publication. And yes, there were balloons.

The fact that the principal characters in this story are little girls adds poignancy, but the coincidence would have been just as extraordinary had they been old men, or millionairesses, or even aliens. Coincidence does not discriminate between gender, race or religion. We all are caught in its web-like embrace. To the axiom that only two things are certain in life, death and taxes, should be added a third – coincidence.

Even after death, coincidence can strike.

Charles Francis Coghlan, one of the greatest Shakespearean actors of his time, was born on Prince Edward Island on the east coast of Canada in 1841.

Coghlan died suddenly on 27 November 1899 after a short illness while performing in the port town of Galveston, Texas, in the south-west of the United States. The distance was too great to send the body back home, so it was interred in a lead-lined coffin in a granite vault in a local cemetery.

On 8 September 1900 a great hurricane struck Galveston – hurling huge waves against the cemetery and shattering vaults. Coghlan’s coffin was washed out to sea.

It floated into the Gulf of Mexico, then drifted along the Florida coastline and out into the Atlantic where the Gulf Stream took over and carried it north.

In October 1908, fishermen on Prince Edward Island saw a long, weather-beaten box floating ashore. After nine years and 3,500 miles, Charles Coghlan’s body had come home. His fellow islanders reburied him in the graveyard of the church where he had been baptised.

Coincidences of the kind which befell Charles Coghlan, or the lucky key lady, Mrs Lovell, are immensely attractive to us. They appeal to our innate need for order and pattern. They make us seem less small and insignificant and the universe less terrifying and aimless. Even the most hard-bitten sceptic can enjoy the most modest of coincidences. Our preference, naturally enough, tends to be for benign coincidences – particularly when we are the recipient of the good fortune. But malign coincidences are also interesting to us – as long as they are viewed from a distance:

At 8.15am on 6 August 1945, Tsutomu Yamaguchi was in Hiroshima on a business trip. Heading for an appointment he heard a plane overhead and looked up at the sky to see two parachutes descending. Moments later, the atomic bomb Little Boy exploded about two miles from the spot where Yamaguchi stood. Even at that distance he suffered burns to his upper body, ruptured eardrums and was temporarily blinded. He managed to stagger to a bomb shelter, and the next day had recovered sufficiently to make the journey back home – to Nagasaki.

On the morning of 9 August, he was describing his experience in Hiroshima to his office supervisor when the second atomic bomb exploded. Fortunately, Yamaguchi again survived to tell the tale.

When coincidence dumps misfortune on our doorstep, we at least have the compensation of feeling that we have been singled out by fate for special attention. Most commonly, however, coincidences are modest, unthreatening and cheering. When we take our dog for a walk in the park and meet a fellow dog-walker with an identical dog – with the same name – it brightens our day.

How often have you been thinking about someone when the phone rings, and it is them? It produces a warm fuzzy feeling, does it not? When such things happen we are tempted to conclude that we are blessed with the gift of extra-sensory perception or are party to some sort of psychic connectedness. We don’t tend to say: ‘Oh that’s obviously the simple laws of probability at work.’ We prefer to see such events as transcending physical laws, as being beyond coincidence. We don’t really want to be reminded that such occurrences are hugely outnumbered by the times the phone rings and it’s someone we haven’t been thinking about.

It is much more satisfying to believe coincidences, particularly the more surprising and unlikely events, are somehow meant to be. If not guided by some universal unifying force, then perhaps they are glimpses of our own innate power to bring like and like together – akin to psychic powers of telepathy, clairvoyance and premonition. Our fascination with both coincidence and the paranormal come neatly together in our passion for horoscopes. Even people who profess to be devout sceptics can be spotted surreptitiously checking their star forecasts.

It began thousands of years ago when our distant ancestors failed to understand that a solar eclipse – during which day turned dramatically and mysteriously into night – was nothing more than the coincidental alignment of a ball of gas and a ball of rock.

Eclipses also, quite naturally, coincided with events on Earth. Chroniclers down the ages have recorded how solar and planetary conjunctions have occurred at the time of famines, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, major military defeats or victories and the deaths of emperors and kings.

Fascination with such conjunctions eventually transformed into the prediction business. Most famously, the 16th-century French astrologer and physician Nostradamus translated his study of the stars and horoscopes into a catalogue of dramatic, if often inscrutable, prophecies. Some credit him with anticipating the French Revolution and the First World War. Recent claims that Nostradamus accurately foretold the September 11 terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York are urban myths.

In 1987, journalist and astrologer Dennis Elwell hit the headlines after he warned of a possible disaster at sea – just days before 188 people died when the P&O car ferry, the Herald of Free Enterprise, capsized off the coast of Zeebrugge, Holland.

Elwell explains the astrological evidence that prompted his warning. ‘Technically the March 1987 solar eclipse was raising the temperature of a square between Jupiter and Neptune, planets which, when working together, indicate both sea travel and big ships. Eclipses bring the matters signified into high profile, and tend to be associated with misfortunes, although positive outcomes are also possible.’

Elwell sent identical letters to two shipping companies, alerting them to the potential hazard. The letter said: ‘The emphasis is on the sudden and disruptive. While I am not in the prediction business, it would be no surprise to find that, at the very least, sailing schedules were upset for some unexpected reason. But there has to be a possibility of rather more dramatic eventualities, such as explosions.’

Only nine days after P&O replied that their procedures were designed ‘to deal with the unexpected from whatever quarter’, their ship, the Herald of Free Enterprise, capsized.

Elwell’s prediction was dramatically and tragically accurate. But was this just coincidence? We don’t hear so much about all the psychic predictions which turn out to be wrong; the foretold disasters which stubbornly fail to happen.

Horoscopes generally restrict themselves to forecasting less dramatic events in our lives. On 5 September 2018, three different national newspaper horoscopes offered a variety of advice for people born between 21 March and 19 April under the sign of Aries. Mystic Meg in the Sun said: ‘An emotional planet pairing boosts family forgiveness. If you are single, love sparks fly when “S” reads out your name.’ Sally Brompton in the Daily Mail advised: ‘You can wait indefinitely for a domestic problem to go away but the fact is that it won’t. Now, with the Sun and diplomatic Venus moving in your favour, you have no excuse for putting off dealing with a domestic problem. Say what you have to say but try to sugarcoat it.’ And Justin Toper in the Mirror said: ‘No matter how tired you are, with Saturn about to go direct, you can expect a massive turn around. Something else should manifest out of the mist today.’

What does it all mean? And what were Arians to conclude if any of those predictions came to pass? Those who believe in the prophetic power of horoscopes use them to guide themselves through crises in their lives, while sceptics will naturally dismiss any apparent correlations between predictions and subsequent events as pure coincidence.

Our faith in horoscopes might be justified if it were possible to demonstrate some causal link between our moment of birth and the movements and interactions of the planets. Astrologers say there is, but they would say that wouldn’t they? Dr Pat Harris tries to bring science and astrology together. She is a practising astrologer who has also run research projects at Southampton University looking at, among other things, the possible impact of the planets on pregnancy and childbirth. She says her research has helped her understand more about the link between astrology and successful pregnancies and she uses her knowledge to help clients improve their chances of having a baby by timing conception attempts with the astrological factors identified in her research as favouring a successful outcome.

After studying the star signs of a number of mothers-to-be she concluded, for example, that there is a strong correlation between the influence of Jupiter and successful pregnancies and healthy births.

But how could Jupiter cause the successful birth of a baby?

‘I can’t say that it does,’ she said. ‘At this stage we can only talk about correlation – or synchronicity, as Jung would call it. When something goes on in the heavens, something goes on down on Earth. They appear to be connected, but we don’t know if one causes the other.’

Astrophysicist Peter Seymour, from Plymouth University, has gone further, and has attempted to come up with a theory of how the planets might have a physical impact on human destiny.

Seymour sees the solar system as an intricate web of magnetic fields and resonances. The Sun, Moon and planets transmit their effects to us via magnetic signals. Magnetism, he points out, is known to affect the biological cycles of numerous creatures here on Earth, including humans.

The planets, he suggests, raise tides in the gases of the Sun, creating sunspots. Particle emissions then travel across interplanetary space, striking the Earth’s magnetosphere, ringing it like a bell. He believes the various magnetic signals are then perceived by the neural network of the foetus inside the mother’s womb, ‘heralding the child’s birth’.

French psychologist Michel Gauquelin devoted his life to trying to find out if there was a scientific basis for astrology. He conducted major studies exploring statistical links between the births of eminent doctors or politicians or soldiers and particular conjunctions of the planets. He discovered, for example, that an unlikely percentage of French professors of medicine had been born when Mars and Saturn were dominant. Mars was also shown to be particularly significant in the birth charts of more than 2,000 leading athletes.

He found many other similar correlations:

By no means all of Gauquelin’s findings came out in support of astrology. His early work on zodiacal signs found no evidence to support the astrologers’ claims. Throughout his life he faced accusations from the scientific community that his findings were inaccurate or even fraudulent. In 1991 he committed suicide, after first destroying much of his original data.

More recent research has thrown up a possible astral link between car thieves and their victims. Using statistics provided by the Avon and Somerset constabulary, it has been discovered that car thieves and the owners of the cars they steal commonly share the same birth sign. The inference is that if you are born under the same sign, you share similar preferences, including your taste in motor vehicles. It’s doubtful how much comfort that will offer the freshly bereaved former owner of a shiny new £300,000 Porsche Carrera GT. What will the thief come after next? His wife?

Amateur astronomer Peter Anderson regarded astrology as ‘bunkum’. One day he found a newspaper lying on a desk, opened by chance at the horoscopes and, despite his innate scepticism, he couldn’t resist glancing at the prediction for his birth sign – Capricorn. It said he would be offered two jobs in the next week. He had a good laugh about it. The next day he was offered two jobs …

Believers in meaningful coincidences win converts every day.