9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Europa Edizioni

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Cold cases are, by their very nature, historical and yet crime narrative non-fiction is almost always written by retired detectives, reporters and criminologists.

While genealogy is beginning to be recognised as a viable tool, there is so much more that historians have to offer. The author is convinced that historians can bring a different skill-set to cold case investigations, taking her on a hunt for a serial killer. In the case of Scotland’s Bible John murders, she goes back to events that happened decades ago, with an engaging and captivating writing style that ranges from historical reconstruction to interviews and analyzing hundreds of documents from an endless bibliography. In the end, she offers a compelling and original theory.

Jillian Bavin-Mizzi - BA (Hons 1st), Dip Ed., PhD is an Australian historian writing cold-case narrative non-fiction. She worked as a lecturer at Murdoch University for nearly ten years, publishing a number of academic works in the field of late-nineteenth-century sexual assault cases. Over time, she became increasingly interested in cold cases and published a first true-crime book, The Wanda Beach Murders, in 2021.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

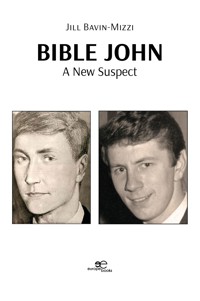

Jill Bavin-Mizzi

Bible John: A New Suspect

© 2024 Europe Books | London

www.europebooks.co.uk | [email protected]

ISBN 9791220149785

First edition: April 2024

Edited by Veronica Parise

Bible John: A New Suspect

For Patricia Docker, Jemima MacDonald,

Helen Puttock and their families.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my family for their incredible support – from their participation in our search of Scottish cemeteries to their sharing of computer expertise. In particular, thank you Hannah for proof-reading my final draft.

I would also like to thank my friends Alan and Arlette Warnock for sharing their reminiscences of and knowledge about their young lives in Scotland. And, of course, thank you to my close friend, Tracie Wright, for listening to the many twists and turns as this manuscript took shape.

I am indebted to Dr Stuart Boyer for trying to teach me about DNA transmission and for lending his scientific expertise to my genealogy. You’re a wonder, Stuart! Thank you also Dr Jeremy Keating for your very valuable assistance with my understanding of the suspect’s much discussed dental features.

Thankyou Gordon and Margaret White for helping me with various cemetery and crematorium records and for going to great lengths to examine the Scotstoun and Bankhead Primary School Registers in the Glasgow City Archives. Thankyou also to Michael Gallagher from the Glasgow City Archives for his generous assistance when I needed it most.

I have repeatedly relied on a private investigator, Keith Coventry, for information which I desperately needed. He never once failed me. Thank you so much, Keith.

But, most of all, I would like to thank June for allowing me into her home and trusting me with her recollections. I have, at all times, tried to stay true to your telling of your own story, June.

Chapter 1.

Finding Patricia Docker - Friday 23rd February, 1968

Patricia Docker’s body lay in a quiet service lane at the rear of Carmichael Place, only yards from her home. The young woman was lying on her back with one of her legs twisted outwards from the knee - naked except for a wedding ring on the ring finger of her right hand. A neighbour called police after finding Patricia early on Friday morning. When Detective Sergeant Johnstone and Detective Constable MacDonald arrived on the scene, at about 8.10am, they found no sign of Patricia’s clothing, but noticed that her right shoe was only partially on and the other was nearby. They saw a used sanitary towel next to her body.1

Police Surgeon, Dr James Imrie, examined Patricia while she still lay in the service lane. He noted her facial and head injuries but concluded that none of these wounds were “serious enough to have killed her.” Dr Imrie also found ligature marks on Patricia’s neck, which indicated to him that she had been strangled. He believed the marks had been made by

something strong, like a belt.2

Photograph published in the Scottish Daily Express, 26th February 1968.

Later that day, Glasgow University Professor, Gilbert

Forbes, conducted a post-mortem. He confirmed Dr

Imrie’s initial findings, establishing the cause of death as strangulation. Professor Forbes believed that Patricia had been beaten and kicked about the head, face and body just before her death. Her right eye had been blackened and there was a laceration on her upper lip. There was also bruising on the right side of her head above her ear. During the post-mortem, Professor Forbes found that, at the time of her death, Patricia was menstruating. While he saw “no clear evidence of sexual assault,” a number of former detectives have stated unequivocally in their memoirs that Patricia had been raped.3

Detective Superintendent Elphinstone Dalglish led the investigation into Patricia Docker’s murder. At the time, he was deputy to Detective Chief Superintendent Tom Goodall. D.S. Dalglish instructed detectives to conduct house-to-house inquiries, fanning out from the service lane. Few people had noticed anything unusual during the night but one neighbour, a schoolteacher, said she heard shouting at “round about midnight”.4 She told police:

I heard a woman shout out, twice in quick succession ‘Let me go.’ It was brief and I never heard it again. I thought nothing of it at the time. It was not followed by any kind of screams or any sort of commotion really.5

When former detective Joe Jackson was interviewed for the 2021 documentary “The Hunt for Bible John”, he explained that he was one of the officers tasked with going from door to door, asking people “if they had heard anything, seen anything, etc.” He recalled the schoolteacher’s evidence and said that nothing else came from the door-to-door inquiries. Nevertheless, for detectives, this one statement established that Patricia Docker had been murdered in the service lane where her body was found. She had not been killed elsewhere and dumped in the laneway.

***

When Patricia Docker had not returned home by midnight her parents assumed that she was staying overnight at a friend’s place but, when she failed to return the following day, they became worried. After reading an article in the evening newspaper about the discovery of a woman’s body in his neighbourhood, Patricia’s father, John Wilson, went to the mobile police caravan headquarters which had been set up in Ledard Road.6 He identified the body of his twenty-five-year-old daughter, Patricia Jane Charlotte Docker. She and her four-year-old son had been living with him and his wife Pauline at their Battlefield home for almost a year.7

John Wilson told police that his daughter had gone out on Thursday night with some friends from Mearnskirk Hospital, where she worked as a nursing-auxiliary. Apparently, the friends intended to go dancing at the Majestic Ballroom. Wilson said that Patricia had separated from her husband of five years after the couple returned from Cyprus the previous April. Alexander Docker, a in the R.A.F., was stationed at Digby in Lincolnshire.8 The Daily Record reported that detectives contacted the base in Digby and the orderly officer told them: “Corporal Docker is on leave, but not, I understand, in Glasgow.” According to police notes, Alex Docker:

went on leave on 19th February 1968 till 3rd March 1968. On forenoon and afternoon of 22nd February he and his girlfriend travelled by train to Haddington, arriving at his parents’ home about 5.30pm. Had tea with parents, then husband and father went for a drink in a local public house, returning at or about 9pm. Remained with parents and girlfriend talking and watching TV. 11.30pm prepared for bed and

slept there overnight. … has no car.9

As Professor Judith Rowbotham, says in an interview for the documentary “The Hunt for Bible John”, police were able to eliminate Alex Docker as a suspect in

Patricia’s murder because he couldn’t have been in

Glasgow at the time, “the logistics were simply not there.”

In the days that followed, police held a number of press conferences, appealing for public assistance. D.S. Dalglish described Patricia Docker “as being about 5ft. 3in. in height, of slim build, and with dark brown wavy hair, cut in a medium short style”. He told the press that she had “hazel eyes, a snub nose and protruding upper teeth.” 10 To this description, D.C.S. Tom Goodall added that, when Patricia left home on Thursday night, she was wearing a grey duffle coat with a blue fur collar, a mustard or yellow knitted-type dress, natural-coloured stockings and brown strap shoes. She was also carrying a brown handbag.11 For their part, the press reported these descriptions of Patricia at length and, as early as the 24th February, they began circulating photographs of her.

On the 26th February, the Daily Record claimed that for “almost five hours”, on the preceding day, four officers from the Police Underwater Unit (known as frogmen) searched a mile of the River Cart, near the end of Carmichael Place. The Scottish Daily Express was more precise about the search area: “The four frogmen searched the shallow water between Weir’s sports ground at Battlefield to the Kilmarnock Road bridge.” Apparently, the frogmen discovered something in the River Cart but D.S. Dalglish refused to release any details. The Evening Times quoted Dalglish as saying only that the frogmen found “something which had a definite bearing on the case.” Years later, writers have suggested that the frogmen found Patricia’s handbag, part of her watchcase and a bracelet.12 Despite a police search of the River Cart embankment on the 4th March, Patricia’s clothes were never found.

Witnesses reported seeing three cars in the vicinity of Patricia Docker’s murder. On the 26th February, for the first time, police appealed to anyone who had seen a lightcoloured Morris 1000 Traveller in or around Battlefield on the Thursday night. They believed the car had pulled over at a bus stop on Langside Avenue near the entrance to Queens Park at approximately 11.10pm. There, the driver picked up a young woman waiting for the No. 34 Corporation Bus. Police also appealed for information regarding a man and woman who were seen driving a white Ford Consul, 375 model, which turned from Braemar Street into Overdale Street at approximately 11.20 pm. Witnesses said that the car was tooted at from behind when it started rolling backwards near the junction of Carmichael Place.13 The couple in the white Ford Consul immediately contacted police and were cleared of any involvement in Patricia’s death but, despite numerous appeals, the driver of the Morris 1000 Traveller never came forward.14

For several days, detectives interviewed anyone who attended the Majestic Ballroom on the night Patricia Docker was murdered. It was estimated that there had been one hundred and fifty dancers at that particular session and police appealed to all of them to come forward. The Glasgow Herald carried their appeal: “We are still making progress, but we would like to interview all the dancers who were at the Majestic on Thursday night. We can assure them that if they come forward their personal backgrounds will be treated in confidence.”15 Meanwhile, the Scottish newspapers continued to print photographs of Patricia Docker.

Despite all of the publicity, it wasn’t until some ten days after Patricia’s body was found that a member of the public told police they had seen her at the Barrowland Ballroom in Gallowgate that Thursday night.16 Detective Chief Inspector George Brownie announced on Saturday the 2nd March that Patricia had attended the Barrowland as well as the Majestic on February the 22nd; that she had “visited TWO city dance halls on the night she died.”17

The press told readers that, after visiting the Majestic

Ballroom in Hope Street, Patricia went to a special over25s carnival dance at the Barrowland. In his memoir Chasing Killers, former detective Joe Jackson argues that Patricia had not attended the Majestic at all that night. The early information they received placing Patricia at the Majestic was incorrect. In Jackson’s own words: “It was some days before we learned that Patricia had, in fact, gone to the Barrowland instead. This led to the first bum steer: a nutcase who had been at the Majestic insisted that he had danced with the murdered woman. His claim was quickly disproved but centring our investigation on the Majestic lost us valuable time.”18

When investigators realised that Patricia Docker had been at the Barrowland Ballroom, they began interviewing staff and dancers there. A number of later writers have suggested that, while none of the interviewees remembered seeing Patricia leave the Barrowland with anyone, some recalled her dancing with “two or three different men” that night. At least one of these witnesses indicated that there was nothing noteworthy about any of Patricia’s dance partners except that one of them “had light red hair” and “was rather good looking.”19

In Chasing Killers, Joe Jackson says that, after Patricia Docker’s murder, “detectives worked fourteen-hour days from 8 a.m. until 10 p.m.”20 But the information they gathered led nowhere. As retired Detective Superintendent

Robert Johnstone says, there were “no clues, no fingerprints, no witnesses.” 21 Detective Superintendent James Binnie, who was also part of the investigating team at the time, later explained that the trail simply went cold and so the investigation was wound down after only two weeks. 22

***

For years, cold-case writers and criminologists have used the available information to construct a narrative of Patricia Docker’s murder, much as I have just done. But, for all of us, the sources are limited. Given that no-one was ever arrested or tried for this crime, there are no court transcripts in existence. What is more, the police files and Patricia’s autopsy report remain closed to the public. Unlike most historical documents, criminal case records are not necessarily opened after a specified period of time. Whenever murder investigations are classified as “ongoing” the relevant documents can remain off-limits indefinitely.

Despite these restrictions on access to information, coldcase writers, criminologists and historians like me are able to reconstruct much of what happened by using details which were deliberately fed to the press by those in charge of the investigation. We also rely on the additional material disclosed, and sometimes even generated, at a later date. For instance, some of the details of Patricia Docker’s murder have been revealed in the memoirs of former detectives and in the work of crime writers or documentary filmmakers who have interviewed various participants in the case. Perhaps even more importantly, a good deal of information was released in 2022 when a journalist named Audrey Gillan used actors to read lengthy passages from the original police reports in her podcast, “Bible John: Creation of a Serial Killer”.

Some writers are interested in going beyond the reconstruction of Patricia Docker’s murder. They search the available evidence for clues in order to continue the hunt for her killer. For example, in their 2010 publication The Lost British Serial Killer, David Wilson and Paul Harrison examine one of the significant clues reported by the Scottish press – the fact that Patricia’s “unclothed” body was found lying in a service lane while most of her effects were missing. Wilson and Harrison argue that Patricia’s killer likely stripped her and removed her clothing from the scene because “he had an understanding of how the police would conduct their investigation … – largely through fingerprints, hair and blood samples, in an age before DNA profiling.” 23 The implication, according to Wilson and Harrison, is that the killer had probably offended before or “had some insight into policing.” 24 Of course, either of these scenarios is possible, but neither was assumed by investigators at the time. Detectives may have reasoned that, if the killer removed most of Patricia’s effects from the crime scene because of some understanding of police procedures, he probably would also have taken her shoes and sanitary towel, both of which he had likely touched.

David Wilson and Paul Harrison go on to suggest an alternative, more plausible, explanation for Patricia Docker’s nakedness – that her killer removed her clothing as a dramatification. In other words, he posed her body to send a message to those who found her. Patricia’s killer stripped her naked and left her in the open for all to see, posed perhaps as the “whore” he believed her to be. If this were the case, then the removal of Patricia’s effects amplified the killer’s message. By taking almost everything away, the killer drew attention to, and hence attributed meaning to, the items he chose to leave.

For instance, the killer left a wedding ring on the ring finger of Patricia Docker’s right hand (despite having taken her bracelet). 25 Positioned as it was, this ring signifies that, although she had married, Patricia was either separated, divorced or simply pretending to be available. The killer may have considered any or all of these options to be a serious moral transgression. It is more difficult to determine the possible significance of Patricia’s brown, strap shoes. It might be that, for the killer, they were evidence of her attendance at a dancehall and were left at the scene, also as a moral statement. 26

Maybe, even the sanitary towel, discarded as it was near Patricia’s body, held some significance for her killer. According to the former Sheriff of North Strathclyde and of Lothian and Borders, Charles Stoddart, detectives “merely noted” the fact that Patricia Docker had been menstruating and recorded it along with the rest of the pathologist’s findings. 27 At this stage, they made nothing more of the sanitary towel.

From a purely practical point of view, the removal of so many of Patricia Docker’s effects indicates that her killer was not travelling on foot. It is inconceivable that he ran from the service lane laden with Patricia’s belongings. This would have meant carrying her dress, coat, stockings, underwear and handbag through the streets of Glasgow. It might even have meant holding them while hailing a taxi or catching a ride on public transport. The implication is that Patricia’s killer used a car. Many years later, the Guardian suggested that: “Though they said little about it at the time, the police assumed that the person who had killed Patricia Docker had taken her to Carmichael Lane in a car.”28 In other words, he had either driven her home from the Barrowland Ballroom or picked her up as she made her way home.

The more likely of these scenarios is that the killer met Patricia Docker at the Barrowland Ballroom. Afterall, the Barrowland was approximately four miles from her home. No-one saw Patricia attempting to walk any part of that distance and there were no sightings of her on any of the local buses.29 In fact, as writer Andrew Hagan suggests in “The Hunt for Bible John,” “the journey between [the] dancehall and the site of her murder is almost completely empty of detail” – so much so that “investigating officers at the time were taken aback by how few people were able to identify her movements that night.”

There were, however, witnesses who remembered seeing a number of cars of interest that night. As mentioned earlier, one of these was the Morris 1000 Traveller. The driver was seen picking up a woman who was waiting at a bus stop on Langside Avenue near the entrance to Queen’s Park. But from that location, Patricia would have been less than half a mile from home. She would not have needed to wait for a bus nor to accept a lift. Years later, Detective Superintendent Joe Beattie asked himself, why Patricia would “be stood at a bus stop so close to her home?” He concluded that it was “unlikely that the woman picked up in Langside Avenue was Patricia Docker.”30

A second car, observed near Carmichael Place, was the white Ford Consul 375. At least one witness remembered the Ford Consul driving along Overdale Street and being tooted at as it rolled backwards near the intersection with Carmichael Place. But the man and woman who had been in the Ford Consul came forward and were discounted by police. It appears that the more important car was the one which tooted at the Ford Consul. Unfortunately, no description of this third car was ever reported in the press. Nor was there any mention of whether the driver continued along Overdale Street or turned left, either into Carmichael Place or the narrow service lane just before it, where Patricia’s body was found the following morning. Investigators must have recognised the possibility that Patricia was a passenger in this third car.

Patricia found

here

Map from streetmap.co.uk

As already noted, after murdering Patricia Docker, the killer tossed some of her belongings into the nearby River Cart. The killer could not have reached the River Cart by driving down Carmichael Place because it turns into a narrow walkway. It seems probable that, instead, he drove along Ledard Street and turned left into Millbrae Road.

The killer may have tossed Patricia’s handbag, watch case and bracelet through an open car window as he crossed

Millbrae Bridge. Indeed, press photographs taken soon after the murder, show police frogmen examining a stretch of the River Cart just beside Millbrae Bridge.31 Much has been made of the killer’s possible exit route. David Wilson suggests, in an article for the Herald Scotland, that this exit route is significant because Patricia’s killer was very likely “returning home, where he would be safe.”32 But identifying this exit route is problematic. If the killer did cross Millbrae Bridge, then he was initially heading south. He may have continued driving in this direction to Glasgow’s outer southern suburbs or even beyond but we cannot be certain of this. Satisfied with having thrown some of Patricia’s effects into the River Cart, he might have turned off Millbrae Road at the next intersection, turning west into Riverside Road or east into Earlspark Avenue. He might even have doubled back towards the city.

The only other information that eventually came to light was that Patricia Docker was seen dancing with two or three different men at the Barrowland Ballroom – one of whom “had light red hair” and “was rather good looking.”33 But there was no mention of this man in any of the newspaper reports of the time. The accounts came from later writers who may well have been influenced by hindsight. It seems more likely that, as Charles Stoddart wrote in Bible John: Search for a Sadist, there were “No witnesses. No descriptions. Not even much circumstantial evidence. And no breaks.”34

There is only one thing that we can ascertain about the killer’s appearance at this point in time and that depends on whether he met Patricia Docker at the Barrowland Ballroom or on her way home from the dancehall. If he met her at the Barrowland then we know that he was, or appeared to be, at least twenty-five years of age. As already mentioned, the Barrowland had hosted an over25s carnival dance on that Thursday night.

Chapter 2.

Finding Jemima MacDonald - Monday 18th August, 1969

Margaret O’Brien agreed to look after her sister’s three children on Saturday evening, the 16th August 1969, so that Jemima MacDonald could attend one of the Barrowland Ballroom’s over-25s nights. Jemima was a single mother and Margaret often took care of her children. Margaret became concerned when Jemima didn’t return to collect her children the following day. She overheard some of the neighbourhood children talking about “a body in a building”.35

They had found a partially-clothed woman sprawled on the floor in a bed recess in a derelict tenement. The woman’s body was only twenty to thirty yards from

Jemima’s flat in Bridgeton’s Mackeith Street.36 At about 10 o’clock on Monday morning, Margaret went to the tenement and found her sister.

Photograph published in the Scottish Daily Express, 19th August 1969.

In her recent podcast, Audrey Gillan reveals police

descriptions of Jemima’s body as it lay in the tenement building:

She was lying face down with her coat half pulled down her back and wrapped up round her waist, as was her kimono skirt. Her shoes were off and her stocking tights removed and torn. Her black patent handbag was missing and has not yet been recovered. The back of her pants and legs were dirty. She obviously had been punched in the face and death was due to strangulation, probably caused by the stocking tights. In addition, tufts of hair had been pulled from her head and were lying on her clothing.

The press mentioned only that Jemima’s large, black imitation patent-leather handbag was missing and mistakenly suggested that so too was her dark brown woollen coat.37 It wasn’t until many years later that anyone revealed that a used sanitary towel had been found near Jemima’s body.38

A post-mortem was conducted later that day but D.C.S. Goodall refused to release any details. In 2019, fifty years after her murder, Jemima’s death certificate was opened to the public. This document records the cause of her death as strangulation. According to later writers, Jemima had been strangled with her own stockings. She had also been severely beaten about the head and raped, despite the fact that she was menstruating.39

Although her death certificate states that Jemima MacDonald was thirty-one years of age when she was murdered, the press repeatedly referred to her as a thirtytwo-year-old “mother-of-three”.40 They published

Jemima’s photograph and printed D.C.S. Goodall’s description of her: “she was 5ft. 7in. tall, slim, had dark hair which had been dyed and was showing traces of fair hair at the roots and front”. On the night she was killed, Jemima “was wearing a black pinafore dress, a white frilly blouse, and off-white, sling-back, high-heeled shoes.”41 Police placed a guard on the three-storey tenement in Mackeith Street while detectives sifted through the rubbish in the flat. If they ever found anything of any significance, it was not reported in the press. Detectives also made door-to-door inquiries in the area, but no-one appears to have heard anything unusual on the night Jemima was murdered.42 D.C.S. Goodall repeatedly appealed to the public to come forward with any information which might prove relevant. He also asked all dancers who attended the Barrowland Ballroom on Saturday night to contact police.

Witnesses did come forward, enabling detectives to piece together Jemima’s movements on the night she was murdered. Jemima had left the Barrowland on foot, walking along Gallowgate and Bain Street. From there, she made her way to London Road, taking a short cut through Landressy Street to James Street. She then continued on towards her home in Mackeith Street. This walk, of less than a mile, would have taken her just over twenty minutes.43

During that time, Jemima MacDonald was not alone. She had been seen talking with a man at the Barrowland Ballroom shortly before midnight and this same man accompanied her on her way home. Indeed, one of Jemima’s neighbours saw them together at about 12.40pm outside 23 MacKeith Street, where Jemima’s body was later found. In the words of the police report, Jemima had appeared unconcerned and waved nonchalantly to her neighbour.44 D.C.S. Goodall told the press that, according to witnesses, the man was between twenty-five and thirty-five years of age, 6’ to 6’ 2” tall and slim in build. Newspapers reported alternately that he had “fair, reddish hair” or “reddish, fair hair”, “cut short and brushed back.” He had a pale, “long, thinnish face” and was well-dressed in a good-quality blue suit with hand-stitched lapels and a white shirt.45

In an attempt to identify the man seen with Jemima MacDonald, Detective Superintendent James Binnie contacted the Glasgow School of Art. He was hoping that someone there would be able to produce a colour sketch of the suspect. The task was accepted by George Lennox Paterson, the school’s registrar. Lennox Paterson knew that a number of witnesses had already described the suspect to detectives but some of them had not been particularly helpful so he asked to interview only two of the witnesses - a young woman and a young man.46 Lennox Paterson believed that, if he questioned them himself, he might learn more about the suspect’s appearance and demeanour and he wanted to capture the witnesses’ general impression of the man in his sketch.

George Lennox Paterson spoke with the young woman first and she was able to describe the suspect’s features “in the most general sense”. She indicated that the man she saw with Jemima MacDonald was very good-looking “in the conventional sense” and implied that he was quite the “ladies’ man.” The male witness confirmed some of the details mentioned by the young woman and said that he too considered the suspect to be good-looking.47

In Bible John:Search for a Sadist, Charles Stoddart argues that George Lennox Paterson recognised the difficulty of constructing an accurate representation of a man who he had never seen. Essentially, Lennox Paterson suggested that he had been tasked with composing his idea of the witnesses’ idea of the suspect’s face. And, after speaking at length with the two witnesses, Lennox Paterson felt that he did not have sufficient information. In particular, he didn’t know enough about the suspect’s eyes or lips so he deliberately left the eyes in shadow and the lips vague. “The whole effect”, Charles Stoddart claims, “resembled an out-of-focus photograph, but with just sufficient clarity to

enable someone to recognise the person depicted.”48 George Lennox Paterson’s sketch of the suspect appeared in thousands of newspapers and on countless posters throughout Scotland. To ensure the widest possible circulation, it was also shown on television. Police then sorted through the scores of responses they received, but none of them led to an arrest. On the 28th August, the Daily Record suggested that the investigation had “developed

into a long, hard slog.”

Sketch published in black and white in Tilly Pearce, ‘The Hunt for Bible John’, DigitalSpy, 4th January 2022, Photo Credit BBC.

***

On the 12th October, two weeks after Jemima MacDonald’s body was found, D.C.S. Tom Goodall died from a heart attack. He was replaced as head of Glasgow City Police by his deputy, Elphinstone Dalglish and Jemima MacDonald’s case was handed over to D.S. James Binnie. By this time, the investigation was winding down. Plain-clothes detectives had been attending dance sessions at the Barrowland for nearly two months to see if Jemima’s killer would return but, towards the end of October, they ceased their inquiries there.49

In an effort to rekindle public interest in the case, Jemima MacDonald’s siblings offered a £100 reward for information leading to the capture of her killer. On the 22nd October, the Scottish Daily Express carried the words of Jemima’s eldest sister, Jean Thomas: “This £100 may just be enough for someone to come forward and give the police the vital clue they need. The money comes from myself, three sisters and three brothers. We know it will not bring Mima back but if the man responsible is caught it may save the life of some other poor woman.”50 The family’s £100 reward has never been claimed.

***

From the outset, the press drew links between the murders of Patricia Docker and Jemima MacDonald. On the 18th August, the day Jemima was found, the Evening

Times reminded readers: “Another Glasgow murder victim, Patricia Docker (25), a nurse, was never seen alive again after attending a dance.” 51 And the press was quick to point out that both women had attended the Barrowland Ballroom.52 Nevertheless, a number of detectives have suggested, over the years, that Patricia Docker and Jemima

MacDonald may have been killed by different men.53 In “Unsolved”, the 2005 documentary for Grampian and Scottish Television, Detective Inspector Billy Little says that, at the time, the two cases were treated separately and this remains the official position.

But the similarities between the two cases are undeniable. To start with, both Patricia Docker and Jemima MacDonald attended an over-25s night at the Barrowland Ballroom. Patricia and Jemima were both mothers without husbands. They were both slim in build and, given that Jemima had dyed her blonde hair brown, they appeared to have dark hair, “cut in a medium short style”. Both women were menstruating at the time they were murdered. In both cases, the killer appears to have escorted his victim almost to her front door, before attacking her. Both women were battered about the head and body and killed in the same way, strangled with an item of clothing. They were then left where they died; their killer having made no attempt to conceal their bodies.54 And these are only the similarities that we know of. As the Evening Times suggested in their 1989 review of the murders, “There may have been other links, but to this day the police have kept them to themselves.”55

However, there is one notable difference between the two crime scenes. Jemima MacDonald’s killer didn’t completely strip her, as Patricia Docker’s killer had done. But rather than indicating that the killer was a different man, perhaps this change in behaviour was simply a matter of practicality. While Patricia’s killer appears to have travelled by car, we know that Jemima’s killer was travelling on foot. Taking all of Jemima’s effects would have posed an enormous difficulty. So, instead the killer took only what he believed he could get away with –

Jemima’s handbag. In other words, even the difference in the crime scenes is not problematic. In essence, Jemima’s killer took something from the scene, just as Patricia’s killer had done.

***

While the murders of Patricia Docker and Jemima MacDonald are officially still being investigated as separate cases, the fact that some senior detectives were prepared to “probe the similarities”, means that they gave themselves the opportunity to pool the information from both cases. This tentative pooling of evidence not only makes more information available, it gives investigators the opportunity to search for patterns in the killer’s behaviour, should he indeed be the same man. This no doubt helps investigators to recognise the importance of certain clues and to interpret them. They can use understandings from one murder to inform their interpretation of clues from the other.

For instance, police initially reasoned that Patricia Docker had either met her killer at the Barrowland Ballroom or been picked up as she walked home. The fact that Jemima MacDonald was seen leaving the Barrowland Ballroom with her killer, strengthened the belief in a Barrowland connection. Detectives realised that the killer may have been stalking that particular venue. The Barrowland’s clientele came mainly from the east side of Glasgow and the dancehall was situated in what was considered to be a very rough area.56 In an interview for

“The Hunt for Bible John”, writer Andrew O’Hagan describes this particular district in Glasgow: “That area, that little triangle of the east end of Glasgow, the area around the Barrowland dancehall, was notorious as a place of theft, criminality, drunkenness. There’s a sense of violence just simmering there.” So, it seems that, for whatever reason, the killer was drawn to this notoriously violent corner of Glasgow in his search for victims.

It is also significant that in both murders, the killer selected his victim from the Barrowland’s age-specific over-25s night, rather than from one of the ballroom’s general dances which would have included younger women. The killer was deliberately choosing women who belonged to an age bracket generally associated with marriage and motherhood. In Dancing with the Devil, Paul

Harrison interviews a Barrowland “regular” who explains that: “it was well known that if you wanted a bit more than a dance, then Thursday night was the evening to visit the Barrowland. Many older women were there, the wedding rings came off and identities were disguised.”57 The same might have been said of Saturday’s over-25s night, known locally as “grab a granny” night. Perhaps, given the Barrowland’s reputation, the killer was looking for women who he believed were available for sex, despite the fact that they were, or had once been, married. It is even possible that he was particularly interested in young mothers. And if, in the killer’s mind, many of the women who attended the Barrowland Ballroom’s over-25s nights were married, separated or divorced mothers who were out looking for sex, then his selection appears to have been based on a perceived moral transgression.

So, among the women who attended the Barrowland Ballroom on the nights that the killer was searching for a victim, were there any other criteria of choice? As noted earlier, both Patricia Docker and Jemima MacDonald were slim in build and appeared to have dark, shoulderlength hair. And both, quite remarkably, were menstruating. In One Was Not Enough, Georgina Lloyd, suggests that, when Jemima’s autopsy revealed that, like Patricia Docker, she was menstruating at the time she was attacked, “a chilling thought” entered investigators’ minds: “Were they seeking some kind of sex deviate? One with a hang-up about menstruation?”58 But, of course, the physical similarities between the victims and the fact that they were both menstruating could be coincidental. It is risky, at this stage, to make too much of these commonalities.

If Patricia Docker and Jemima MacDonald were indeed killed by the same man, the fact that he returned to the Barrowland Ballroom to select his second victim suggests that he was not too concerned about being recognised or identified. The same insouciance is reflected in the brazen act of walking Jemima MacDonald home, giving witnesses the opportunity to see the two together. And these actions came at a cost. A number of witnesses did see the killer with Jemima, both in the Barrowland and while he was escorting her home. What is more, these witnesses were able to provide a good deal of information about his appearance. As mentioned earlier, they noted his fair reddish hair, or reddish fair hair, which was, as the sketch shows, cut short, parted to the left and swept to the right. They also described him as being 6’ to 6’ 2” tall and slim in build, as having a pale, “long, thinnish face” and being very good looking in the conventional sense. And they estimated that he was between twenty-five and thirtyfive years of age, which is consistent with the fact that, on both occasions, he attended the Barrowland’s over-25s dance nights.

Of interest too, are descriptions of the killer’s clothes. A number of witnesses recalled the man being “welldressed” in a “good-quality” blue suit with hand-stitched lapels. The impression conveyed by the killer’s clothing, as indeed by his appearance, is one of a man who was both meticulous and conservative. He was noticeably neat and formal for the late 1960s. This killer was no hippy. What is more, the immediately recognisable

“quality” of his suit suggests that he was relatively welloff, or at least wanted to be viewed that way.

It is also significant that in both Patricia Docker and

Jemima MacDonald’s murders, the killer made no attempt to conceal his victim’s body. This means there was no delay in their discovery and the subsequent investigations into their murder. This lack of any attempt to conceal a murder victim is often taken as an indication that the killer is proud of his work or that, at the very least, he is not ashamed of what he has done. While in Patricia Docker’s case the killer appears to have posed her body to send a moral message, there is not as much evidence of this in Jemima MacDonald’s case – though clearly her coat and skirt had been pulled up around her waist and her shoes and used sanitary towel were again left near her body. But, without the removal of the rest of her effects, any intended message seems to have been lost for those who found her. Certainly, if detectives made any meaning from Jemima’s crime scene, their thoughts were not revealed in the press. Nor have any former detectives revealed their analyses in their memoirs.

Chapter 3.

Finding Helen Puttock - Friday 31st October, 1969

Helen Puttock’s body was found soon after 7am on Friday 31st October 1969, lying face down in the backcourt of 95 Earl Street, Scotstoun, about a hundred yards from her home. A neighbour named Archie

MacIntyre noticed what he thought was a “bundle of rags” in the enclosed, grassed courtyard at the rear of his flat. Macintyre later told the press: “I got a terrible shock to find it was a woman. I didn’t know at the time if she was dead or not.” MacIntyre said that Helen’s clothes were in disarray: “She was still wearing her coat but it was pulled roughly up over her head”.59 According to the Evening Times, Archie MacIntyre ran upstairs to his neighbour, “to phone for the police and [an] ambulance.” After failing to rouse anyone, he hurried across the road to a phone booth.60

Photograph published in Charles Stoddart’s Bible John: Search for a Sadist.

When D.C.S. Dalglish and Detective Superintendents Binnie and Beattie arrived in the Scotstoun backcourt, they noticed that Helen’s dress had been ripped and her underslip pushed up above her breasts. Her brassiere was torn in two.61 The cause of Helen’s death was indicated by the piece of underwear still tied in a reef knot around her neck.62 In the 1990s, journalist Audrey Gillan was given access to D.S. Joe Beattie’s notes and again she has included them verbatim in her podcast: