Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CompanionHouse Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

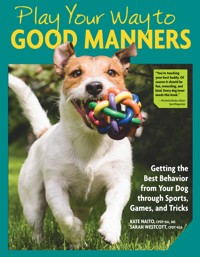

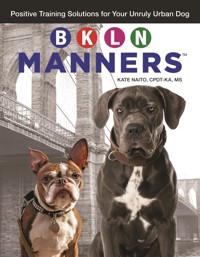

Nearly every client who contacts professional Brooklyn dog trainer Kate Naito (CPDT-KA) is desperately looking to stop his or her dog's undesirable behavior. In response, Kate developed BKLN Manners? as an empowering four-week group class for busy owners who want the fastest path to a polite dog. Now available in book format, this comprehensive system utilizes clever management techniques and positive training strategies to help owners transform their dogs from unruly to urbane. BKLN Manners offers no-nonsense, easy-to-implement solutions to: B: Barking; K: Knocking people over; L: Leash walking problems; N: Naughty when alone. This book addresses uniquely urban challenges like dodging chicken bones on the sidewalk, counterconditioning on crowded streets, neighbors? noise concerns, and more. Written in a problem-and-solution format with the needs of busy urban and suburban dwellers in mind, it can help your dog acquire polite BKLN Manners both indoors and out. Inside BKLN Manners Comprehensive training guide that addresses common behavior concerns of urban and suburban dog owners. Clever management techniques and positive training strategies that help owners transform their dogs from unruly to urbane. The author is a Certified Professional Dog Trainer at a Brooklyn dog training organization who developed BKLN Manners? as a four-week group class for busy owners who wanted the fastest path to a polite dog. BKLN Manners offers no-nonsense, easy-to-implement solutions to: B: Barking; K: Knocking people over; L: Leash walking problems; N: Naughty when alone. Includes a suggested weekly plan for practicing BKLN behaviors and a chart to track training progress.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 375

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BKLNMANNERSTM

CompanionHouse Books™ is an imprint of Fox Chapel Publishers International Ltd.

Project Team

Vice President-Content: Christopher Reggio

Editor: Amy Deputato

Copy Editor: Laura Taylor

Design: Mary Ann Kahn

Copyright © 2018 by Fox Chapel Publishers International Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Fox Chapel Publishers, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

ISBN 978-1-62187-125-5

eBook ISBN 978-1-62187176-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Naito, Kate, author.

Title: BKLN manners : positive training solutions for your unruly urban dog /

by Kate Naito, CPDT-KA.

Description: Mount Joy, PA : CompanionHouse Books, [2018] | Includes index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2017052685 (print) | LCCN 2017059370 (ebook) | ISBN

9781621871767 (ebook) | ISBN 9781621871255 (softcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Dogs--Training.

Classification: LCC SF431 (ebook) | LCC SF431 .N35 2018 (print) | DDC

636.7/0835--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017052685

This book has been published with the intent to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter within. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the author and publisher expressly disclaim any responsibility for any errors, omissions, or adverse effects arising from the use or application of the information contained herein. The techniques and suggestions are used at the reader’s discretion and are not to be considered a substitute for veterinary care or personal dog training advice. If you suspect a medical or behavioral problem, contact your veterinarian or a qualified dog trainer.

Fox Chapel Publishing

903 Square Street

Mount Joy, PA 17552

Fox Chapel Publishers International Ltd.

7 Danefield Road, Selsey (Chichester)

West Sussex PO20 9DA, U.K.

www.facebook.com/companionhousebooks

We are always looking for talented authors. To submit an idea, please send a brief inquiry to [email protected].

Preface

About BKLN MannersTM

As a dog trainer in Brooklyn, New York, I’ve learned that diversity is not limited to people. The dogs I work with every day run the gamut: snorting French Bulldogs, athletic Border Collies, rescue dogs from nearly every continent, designer dogs like Maltipoos to Puggles, blind and deaf dogs, and the list goes on. While these dogs may appear quite different, there is a common theme among them. When their owners contact me for help, nearly every request emphasizes the word stop. “Max needs to stop pulling.” “I want Molly to stop eating garbage on the street.” “I wish Sam would stop barking at noises in my building’s hallway.” And, being an urban dweller, I understand these very normal human concerns. None of us wants to get complaints because the dog’s barking has been waking up the neighbors, and you can extract a half-eaten bagel from your dog’s slimy jaws only so many times before losing it.

Prior to becoming a trainer, I was that exasperated owner bemoaning my dog’s out-of-control barking and embarrassing leash-walking habits. My dog Batman, a then-young Chihuahua mix, had the typical vociferous Chihuahua reaction whenever our doorbell (or even the neighbor’s) rang, and he spent most of our walks practicing for the Iditarod, doing his best to drag me down the street. I tried using the methods of training I’d grown up with, which emphasized being a confident leader to my dog and “correcting” him when necessary. However, I wasn’t actually feeling self-assured in my leadership abilities, and both my dog and I became confused and frustrated, eventually giving up on training because it seemed that only certain people had the necessary character to handle a dog properly—and I wasn’t one of them.

Daily walks had become so full of miserable leash corrections that the mere sight of the leash sent my poor pup into hiding under the bed. I felt terrible. It wasn’t until I took a leash manners class with Sarah Westcott, founder of Doggie Academy, that I realized I could replace Batman’s rude behaviors with polite ones without using punishment. I remember the fourth and final class, during which the dog-and-handler duos walked around a city block full of the usual obstacles: bags of garbage awaiting pickup, discarded pizza crusts, workmen smoking on their breaks, kids whizzing by on scooters. The entire time, Batman only had eyes for me. There were no leash corrections, no harsh words, but rather the occasional treat for polite walking and gentle cues to tell my dog to leave those obstacles alone. Even better than the loose leash walking itself was the new appreciation I had for my dog. We were communicating and walking together as a team rather than fighting each other. Those four classes changed everything.

Shortly thereafter, I pursued a career in dog training with Sarah as my mentor, and together we’ve worked to adapt tried-and-true positive training techniques to the unique needs of our busy urban clientele. So as you leave your apartment, cringing because your dog is howling like a maniac, or as you get dragged from one shrub to the next on your walks, remember that I was once there, too. And now I’m here to help.

Many dogs have learned basic obedience but still have trouble in their daily lives with barking at noises, jumping on people, walking on leash, and engaging in naughty behavior when left alone. Learning the basics is useless if you can’t apply those skills to real-life situations, so I developed a group class at the Brooklyn Dog Training Center called BKLN Manners™ in 2016. As both a class and a book, BKLN Manners™ aims to teach you a few simple behaviors and give you the tools to practice them methodically so that ultimately your dog will be able to remain calm and polite even when faced with the perpetual distractions our urban environment throws at us. With consistency and practice, it’s possible that your dog can greet strangers without jumping into their arms, walk through a crowded farmers’ market on a loose leash, or accompany you to an outdoor café without stealing anyone’s sandwich.

Introduction

It’s a Mad World

Every dog trainer has certain clients she’ll never forget. Pogo, the aptly named Goldendoodle puppy who came to his new Brooklyn family fully equipped with an internal trampoline, still stands out. When guests came through the front door, Pogo introduced himself with WWE body-slams and turned their sleeves into fishnet from all his playful biting. When the family left for work, Pogo took to howling and thrashing so intensely in his crate that neighbors above, below, and on both sides were complaining. His leash-walking acrobatics entertained passersby with a free Cirque du Soleil performance, though sometimes he took a break to help rid the Brooklyn sidewalks of their ubiquitous chicken bones and food wrappers.

Pogo’s kind but exasperated humans had raised dogs before, but not one like this. Never a Goldendoodle, and never in a city. I awoke one morning to their tearful late-night voicemail: “He’s crazy! This is not normal! He’s not like this when we go to our country home. My vet thinks he needs to be medicated.” And I can only imagine that Pogo, just doing what Doodles do, was thinking the same thing about his humans. In fact, Pogo was perfectly normal; it was his humans’ world, with its leashes and doorbells and off-limits chicken bones, that was crazy.

City streets offer a lot of distractions for dogs.

Normal is subjective. That holds true for people from different backgrounds or cultures, and even more so for different species. Take the concept of personal space. Imagine you are standing in line at the post office, with a gentleman you’ve never met in front of you. A typical American will put roughly an arm’s length of space between him- or herself and the gentleman in front; any closer than that would begin to feel uncomfortable. People from Mumbai might put only a few inches between individuals, with each person close enough to feel the breath of the person behind. (Americans, are you cringing yet?) And if Pogo were in that line, well, he’d jump right up onto that man’s shoulders and slobber all over his back. The thing is, there is no right or wrong here, no good or bad, just different interpretations of what normal means. The problem for dogs is that they’re participants in our world, and we expect them to follow our rules—and what crazy rules they must seem to be. Consider these examples:

When Pogo’s exhausted family left me that late-night voicemail, they said something that stuck with me: “He’s not like this when we go to our country home.” This reveals how the problem is not the dog himself; rather, has to do with the circumstances into which we put the dog.

When I was growing up in rural Connecticut, we rarely had to deal with problems such as incessant barking or difficult leash walking. Our family dog, a Golden Retriever mix who just wandered into our lives one day (and who I named Cindy as a tribute to Cyndi Lauper, whose style I shamelessly emulated), lived what most dogs would consider a “normal” lifestyle. She chose to stay outside from morning until evening, wandering around the property and interacting with other dogs and livestock while we humans were at school or work. Cindy had the autonomy to walk, poop, and sleep when she liked, and, as with most of the other dogs in our area, she developed good social skills on her own. That’s not to say she was friendly to everyone, but if she didn’t like certain people or other dogs, she had the freedom to simply avoid them or give them ample warning that they should stay away. Because of this, confrontations were infrequent.

Please Note

For consistency and clarity, I have generally designated humans as she and dogs as he in the following chapters. I have chosen the term owner to identify the person living with a dog because it is a widely understood term; nevertheless, the word falls painfully short of describing described in the text, are rescues. This in no way implies that adopted dogs need more training than other dogs. Rather I aim to show that a rescue dog, weather adopted at eight weeks or eight yearrs, is just as trainable, polite and adored by his family as any other.

Of course, there were certain risks to leaving dogs unsupervised, and Cindy’s playmates were occasionally involved in accidents with cars or other animals. (Were I to live that lifestyle again, I would take more precautions than we did back then.) But, in general, these dogs lived happy, easygoing lives. The only time we ever used a leash on Cindy was to go to the vet. I’m sure her leash skills were horrific, but in the context of a rural lifestyle, it really didn’t matter. Did she bark at the doorbell? Well, I don’t think we even had a doorbell, and she was outside anyway, ready to size up whoever walked over.

In my early twenties, I moved to a cramped Boston apartment after college, and I immediately adopted a three-legged sato (Puerto Rican stray dog) who, despite the indignity of my naming her Three, became my doggie soul mate. In the city, I saw dogs put into a very different lifestyle. Three’s routine was the polar opposite of Cindy’s. My Boston life was busy, structured, and stressful, and somehow I expected this scrappy little street dog to adapt to a confined lifestyle. Though she did adjust remarkably well, I certainly went through my fair share of replacing chewed furniture, scrubbing pee stains, and regularly extracting dead animals from Three’s jaws. I also learned what happens when, due to the restraint of the leash, dogs are forced to face what scares them and aren’t able to engage in the normal reaction of fight or flight. Three, unable to practice flight by walking away from triggers like moving cars or children, turned to fight.

She felt she had to defend herself with the only tool she had: her teeth. Seeing my dog so stressed by living in a world that never gave her space or freedom, it became clear how much pressure we put on our urban dogs: they are expected to walk calmly on short leashes and ignore everything out of reach, to remain quiet when left home alone for long periods, and to tolerate frequent interruptions by doorbells, sirens, and delivery people. We’re asking a lot of our dogs to live by our crazy human rules.

The good news is that both you and your dog can live together peacefully amid the chaos of a city, and it doesn’t take as much effort as you might think. You don’t need to quit your job to train your dog full-time (but wouldn’t that be nice!), and your dog doesn’t need to be able to balance an upright broom on his snout or jump through hoops of fire. In reality, by building clear communication with your dog and teaching him a handful of useful, straightforward behaviors, you can show your dog how to behave in ways that are polite to humans as well as rewarding for him. At the very least, this will require you to make some minor adjustments to your routine; at most, it will involve practicing and perfecting a few key training behaviors and learning how to apply these behaviors to various indoor and outdoor situations, all of which are outlined in the chapters that follow.

I know you’re busy, so in true Brooklyn style, this book gets right to the point. It will address the most common dog behavior problems that urban owners face and provide practical solutions to getting a polite dog both indoors and out. Chapters 1 and 2 lay the foundation for training. Starting with Chapter 3, you can read the chapters in any order, depending on what your most urgent need is. Rather than give you a broad list of tricks and commands that you might never use, BKLN Manners™ focuses on fully developing a few polite behaviors and giving clear instructions for applying these behaviors to a variety of real-life situations. Nevertheless, if you’d like to learn additional city-friendly behaviors, such as Heel through intersections, Sit-Stays at crosswalks, Recalls at the park, or Drop Its for garbage on the sidewalk, you’ll find the steps for these cues outlined in Chapter 7.

While all training takes time, commitment, and consistency, I will provide you with training solutions that can be smoothly integrated into your regular routine. In many cases, it doesn’t take any extra time at all because you can train while you’re already walking or spending time with your pup. The book is organized so that you can identify the problem you’re having and then read through the different strategies to help. You’ll notice that each chapter has multiple management and training strategies to modify your dog’s behavior issue. See which strategies fit your lifestyle best. It is more effective to practice one strategy thoroughly than to superficially try many different ones. Dog training is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor; it is a unique experience based on your needs. If I see three clients in a row who all need help with leash walking, it’s possible I will use a different strategy for each, depending on the dog’s temperament, the owner’s patience and interest in training, the external environment, and other factors.

This book covers four main areas of dog behavior that we consider problematic, with one chapter devoted to each:

Within these chapters are more specific problem-and-solution sections. You’ll find that there is some overlap; for instance, a dog who jumps on passersby while walking with you on leash falls into both the K and L chapters. You’ll also find that there is more than one problem in each chapter because, as you may have experienced, a dog can bark in more than one circumstance or may have more than one undesirable behavior while walking on leash. When you are ready to start training, check out the Appendix, which includes charts to track your progress.

And what about Pogo the Goldendoodle? I worked with his family for several sessions in their home, where he learned the foundation of being polite as outlined in Chapter 2. Later, he was one of the first graduates of my BKLN Manners™ group class. For walks, Pogo’s family has learned how to teach Pogo polite behaviors, like sitting, rather than jumping on people, and when they know he is too excited to sit, they apply pain-free management strategies instead. Now, instead of mauling incoming guests with love, Pogo either takes a break in the bedroom while guests enter, or he sits politely on his mat until he is released. His home-alone freak-outs have been reduced from constant screams to a few whimpers now that he is getting the exercise and stimulation he needs. Walks are just that: walks. Pogo’s acrobatics have subsided, and his humans have the tools to divert him from the sidewalk garbage buffet.

Is he a perfectly mannered gentleman all the time? Of course not! He’s a dog, and still a young one at that. The last time I spoke to Pogo’s family, I reminded them that training isn’t really about what the dog does but about how the human reacts. Even the most well-behaved dog will do things that humans find undesirable. Fortunately, with some time and practice, we owners can learn how to prevent these rude doggie behaviors from happening. Pogo’s family has learned how to address Pogo’s doggie needs in a way that fits their busy urban lifestyle, and, as a result, everyone in the family is more at ease and learning together.

Chapter 1: Think Positive

The key to good doggie manners is preventing bad ones rather than doing damage control once the dog has already made a mistake. With every jump on a horrified houseguest, your dog will be reminded how much fun it is to jump on people, especially when—oh, goodie!—they squeal and thrash like squeaky toys. The habit becomes increasingly difficult to break because it is inherently enjoyable for your dog. Instead of struggling to calm down a dog who is already jumping wildly, prevent this habit from starting. If you know guests will be arriving at 4:00 p.m., get your dog happily in his crate or confined to your bedroom with a treat-stuffed toy by 3:55. Don’t wait for the doorbell to ring and his doggie brain to explode.

As I mentioned in the Introduction, dog training actually has little to do with your dog. It has everything to do with how you react to your dog’s behavior. My clients at Doggie Academy often assume that my own dogs are perfectly behaved at all times, as if they’re finely tuned robots just awaiting my instructions. These owners sometimes gasp when I reveal, “No, no, trainers’ dogs misbehave all the time!” Go to any obedience competition or other dog sport, which is full of professional trainers, and you will see dogs with behavior issues such as reactivity to other dogs, excessive barking, and overexcitement. Trainers simply know how to nip those issues in the bud. For example, in the case of excitement barking, a trainer will be in tune to her dog’s emotions, able to pick up on the dog’s subtle signs of excitement that come before the barking starts, and thus able to prevent the barking before it happens. If the dog has already barked, a trainer will immediately address it by asking the dog to perform a calm behavior to change his focus, thereby stopping the barking without force. You will never see a good trainer let a dog get completely out of control and only then try to correct the behavior. By following the steps in this book, you can channel your inner dog trainer to help your dog engage in polite, rather than rude, behaviors.

When following any given training strategy in this book, there will be several steps. Follow each step in order, and resist the temptation to skip steps. Often when dogs don’t behave as we’d like, it’s because we’ve pushed ahead too quickly and they’re confused about what we’re asking them. When training, you and your dog are learning a language together, so it’s vital to take baby steps forward and make sure you’re communicating clearly at each step. If you’ve ever taken a language class in school, you know what happens if you skip a few lessons and then try to catch up. You’re totally lost, and now your instructor is speaking indecipherable gibberish reminiscent of the adults in Peanuts cartoons. At this point, you’re so stressed and confused that learning the language is pretty much impossible. As you train your dog, think of yourself as a language teacher who ensures that the student fully understands Lesson 1 before proceeding to Lesson 2. Go step by step with your training, and if your dog struggles at any point, revisit the previous step as outlined in the instructions.

To Treat or Not To Treat?

Most of us don’t work for free. Because we know our company will pay us, we do all kinds of things we wouldn’t otherwise do: wake up before sunrise, smile at coworkers before we’ve had our coffee, wear a uniform, and the list goes on. If we knew our company wouldn’t pay us for our efforts, I’m sure most of us would quit—or at least slack off. So why is it that we think our dogs should work for free? For dogs, rewards, such as treats, are payment for a job well done, and you’re the boss who has the ability to dish out those rewards. So be a good boss and pay your dog well, especially for difficult tasks like sitting when he’d much rather be jumping. This is the philosophy behind positive training, the form of training that I advocate because it is backed by extensive scientific research and has been proven to improve your dog’s behavior in a way that is enjoyable for both of you.

Ask yourself, “What motivates my dog?” For most dogs, tiny pieces of training treats (including bits of “real food,” like chicken, hot dog, or cheese) are highly motivating and easy to dispense. It is true that some dogs will gladly work for the reward of a “Good boy” and a pat on the head—and that’s great! But if your dog doesn’t fall into that category, be prepared to pay him in a currency that motivates him.

At the early stages of training, rewards accelerate the learning process because the dog gets excited to train with you and thinks, Last time I put my rear on the ground, I got a cookie. I’m going to try that again! The harder the task, the better your reward should be. There are generally two scenarios that make a task “hard” for the dog:

You are teaching him to do a new behavior. This could be something entirely new, like teaching him to lie down for the first time, or it could be a more difficult level of a behavior he already knows, such as a Stay for ten seconds when you’ve only practiced five-second Stays before. Your dog is working really hard here, and a super-tasty reward (or high-value reward, as trainers call it) will keep him in the game.You are asking him to do something in a new or distracting environment. Asking your dog to sit in your living room is one thing; asking him to sit at a crosswalk in Times Square is another. When your dog is in a new, stressful, or distracting place, be ready to reward him handsomely for listening to you.It’s easy for dog owners to underestimate how hard their dogs are working to be polite, especially when being asked not to jump, not to bark, or not to pull on the leash. Granted, it doesn’t look terribly impressive when a dog is sitting politely at a crosswalk, but think of it from the dog’s perspective: he is surrounded by interesting smells, tasty-looking food wrappers, noisy vehicles, and other dogs and people. Asking him to sit in that situation is asking him simultaneously to not do about ten other things that he’d rather be doing, and that’s very hard work. Therefore, in the early stages of training, the reward needs to be sufficiently motivating to keep him “in the game” with you.

I regularly see clients who believe that their dogs are not interested in treats, and while this is occasionally true, most of the time it’s that the owners are asking their dogs to do something very difficult (such as sit in the presence of distractions) but not paying them adequately for it. When I teach a dog how to do a Sit-Stay indoors, I generally use a low-value treat, like kibble. When I teach the same dog the same Sit-Stay at a crosswalk, I upgrade to hot dogs because I’m asking the dog to pay attention to me and ignore all the excitement around him, which is no small task. Once the dog has gained more impulse control and can more easily do the Sit-Stay at the crosswalk, I can reduce the frequency and tastiness of my rewards.

Occasionally, your dog deserves a “jackpot”—a series of several treats in a row to reward a really great response or the completion of a difficult behavior. While dogs don’t seem to notice the difference between a large treat and a small treat, they definitely know the difference between one treat and a series of treats. Being rewarded with a jackpot is like getting an A+ on an extra-difficult exam; you’re left with a glow because your hard work was well worth it, and you feel more motivated for your next task.

Beyond treats, there are other rewards you can incorporate into your routine:

After your dog comes to you when called, reward him by tossing a toy or briefly playing tug. What fun it is to come to my human! I hope she asks me to come again, he thinks.Give the dog his meal only if he sits while you put the bowl on the floor. You were going to feed him anyway, so why not ask him to be polite for his dinner?Have him sit or lie down before being allowed on the sofa or bed. I usually have no problem with allowing my dogs on the couch with me, but they have to ask “Please” by sitting or lying down to get invited up.Only put on the leash if your dog is sitting. Here, the opportunity to get leashed up is the reward. Only let the dog out the door if he sits and waits until you say a release word, such as “OK.”These kinds of “life rewards” accelerate your dog’s manners training because he is learning to be polite for whatever he wants throughout the day. Sitting is a behavior that doesn’t just get him a cookie during training sessions, it also gets him whatever he wants in his regular routine. With consistency, he learns that whenever he wants something, he should sit quietly. And then you’ll find him offering the Sit whenever he wants something, without even being asked. Good dog!

Sitting and waiting for the “OK” to eat.

This rewards-based style of training might be different from what you grew up with or even at odds with what some trainers in your area are promoting. The problem with the older, largely outdated “dominance” style of training is that it often relies on pain- and fear-inducing tactics to compel a dog to behave. While advocates of that method might say that they are teaching dogs to “respect” their owners, I am not convinced that dogs have the capacity for respect; respect is a loaded word that describes a rather complex relationship between two individuals. It is widely accepted that dogs have basic emotions such as fear, happiness, anger, and anxiety; however, it has not been proven that dogs have complex emotions that require reflection, including guilt and respect.

Books about dog cognition and behavior, such as Dog Sense by John Bradshaw, have gone in-depth into this topic using recent research. Those trainers who demand that dogs respect them may at times resort to techniques that are simply hurting or scaring the dogs. If my dog doesn’t sit, I pop him with the choke chain, and he sits to have that pain relieved. Yes, it works, but is that because the dog respects his owner as his leader? Or simply because he wants that pain to stop? This kind of training can easily be misused, eroding the trust between you and your dog and making your dog defensive around you. Training should not be a battle of wills or a struggle to be on top because it puts you at odds with your dog, and, as a result, nobody wins. Rather, training should be fun and simple enough for anyone, kids included, to do without the risk of hurting or scaring a dog. It should be something you and your dog do together.

Positive training techniques, on the other hand, are proven to be very effective in teaching polite behaviors, with the added benefit of building clear communication and a lifelong bond with your dog. With positive training, when the dog doesn’t sit (or lie down or stay) as you’ve asked, rather than punish him, you simply withhold the reward, which is “punishment” enough to a dog. Then ask yourself why he didn’t sit. Did you use a different tone of voice this time? Were you standing farther away from him? Did the phone ring at the same time, distracting your dog? In all of these cases, it’s not the dog’s fault that he didn’t sit. It’s the human’s mistake for either asking the dog to sit in a way he didn’t understand or asking the dog to sit it in a context in which it is currently too difficult for him to concentrate. When the focus is on clear communication rather than dominance, you and your dog can learn as a team.

Management versus Training

Let’s say your dog jumps on the sofa without permission, and you’d like him to stop. What should you do? Well, the answer depends on several factors, ranging from the amount of time you have to train to the layout of your home.

Management is generally the easiest option, as it doesn’t require actual training. Essentially, when you manage the space around you, you create an environment in which the dog can’t engage in the bad behavior. For example, if you don’t want your dog jumping on your sofa while you’re out, lay a folding chair across it. Now the sofa isn’t soft anymore, and your dog won’t be interested in lying there. Don’t have a folding chair? You can also manage the space by blocking his access to that room: shut certain doors, use a baby gate, or put him in a crate. Management is the appropriate choice when you can’t dedicate time to training or when you’re not there to monitor your dog (because you can’t train if you’re not present).

Though management is generally easier to implement than training, it doesn’t actually teach the dog to be more polite. You are simply preventing the undesired behavior from happening by blocking the dog’s access to whatever is causing the problem. When the sofa is unprotected, your pup will likely hop back on it. There is nothing wrong with the management approach, as long as you realize its limitations.

Training, on the other hand, is when we teach our dogs to do a polite behavior instead of the bad one. While I don’t have a problem gently telling a dog “No,” it’s necessary to follow it up by telling him what to do instead. This, of course, takes some time to practice. In the case of jumping on the sofa, one simple training strategy is to teach the dog to sit before being invited onto the sofa. By sitting and asking “Please,” he can have the reward of the sofa. Additionally, I would teach him a cue to go to his doggie bed because there are times when I don’t want the dog on the sofa, regardless of how politely he asks. Notice that by telling him to go to his own bed, I’m not just saying “No” to the sofa but also giving him instructions on where to go instead. Training is the way to have a truly polite dog, because it teaches your dog life skills that allow him to interact peacefully with you, your family, and your friends.

Imagine that your dog has learned how to jump up on your kitchen counter and help himself to anything and everything in your cupboards. What would you do? The management strategy is to block the dog’s access to this area. Close doors, use gates (open floor plans be damned!), use child safety locks to protect the cupboards, or crate your dog. All of these measures will prevent the problem behavior, but it may not actually train the dog to stay off the counters.

What about training your dog to stop counter-surfing? You can certainly do this, but just remember that every “No” should be followed with a “Do this instead.” Two of the strategies explained in later chapters would apply. One option is to teach a Leave It cue, which instructs your dog to walk away from the counter. Leave It basically tells the dog, “Stop approaching that tempting place and walk away instead.” Another possibility is teaching the dog that the kitchen is off-limits (but remember that you can only enforce such a rule when you’re home). When you’re in the kitchen cooking something delicious, send your dog out of the room and have him lie down on his bed or mat, which you can place right outside the kitchen. This is a variation of Place from Chapter 3, which tells the dog to go relax on his bed rather than to sniff around, looking for trouble. For counter-surfing or any other number of problems, such as begging at the table or dashing out an open door, Place prevents the problem from happening. Prevention is always a better strategy than doing damage control once the dog has already stolen your Thanksgiving turkey from the counter or run out the door as you were signing for your package.

In many cases, a combination of training and management strategies is often the best approach, using management to ensure that the bad habit doesn’t continue when you’re not home. Even when you are home, management stops the unwanted behavior from occurring; during that time, you can train your dog to behave differently in the presence of his triggers, whether it’s food on the counter or a squirrel crossing your path during walks.

For a dog who is accustomed to his crate, the crate can be a helpful management tool.

Sequence for Training

When it comes to communication between you and your dog, it’s a little different from the kinds of communication we’re used to. (However, the positive training techniques we use to train our dogs can also be used to train spouses or kids! Karen Pryor explains how to use positive reinforcement with animals and humans alike in her classic book Don’t Shoot the Dog.) When teaching your dog to lie down, for instance, what you do after the dog lies down is far more important than what you did before he lay down. What that means is that your cue to lie down doesn’t teach him much; it’s by “marking” and “rewarding” the correct Down position that you are actually teaching him. This is the typical sequence for teaching a dog a brand-new behavior:

Cue Princess to lie down. At first, you may need to lure her into position with a treat so she can follow the scent downward. Princess lies down.

Mark it. The moment Princess is fully lying down, say “Yes!” Why? “Yes” is a word that we generally don’t use around our dogs otherwise, so the dog will make a clear connection that the word “yes” means “good job; a reward is coming.” You may also click with a clicker (see page 24) or use a different verbal marker, such as “Good dog!” (If you want to get technical, trainers tend to avoid “Good dog/boy/girl” because we also tend to use it when Princess is simply being cute or funny, but we rarely say “Yes” to a dog in other situations.) The word itself is not so important, as long as you use the same word every time and say it at the exact moment the dog does the desired behavior. Marking the desired behavior is the way Princess learns what we want her to do.

Reward it. In the early stages of learning, rewards serve to encourage the dog to try the behavior again. It was so rewarding the first time, why not lie down next time, too?

Marking and rewarding go hand in hand. Marking identifies the behavior we want, and rewarding encourages the dog to do it again. If you mark too slowly—for instance, after Princess has popped back up from the Down—there is the chance that you’re marking the wrong behavior, and she will learn that “Down” means “lie down and stand up quickly” rather than “lie down and stay down.” Rewards should come pretty quickly after the verbal marker, within a second or two of marking, especially when you’re teaching a new behavior. Always reward Princess while she’s still doing the desired behavior. In this case, reward her while she’s lying down so she learns how awesome it is to lie down.

If Princess starts to lie down but then pops up into a stand, we mark that moment, too. We use a no-reward marker (NRM) like “Oops” or “Uh-uh” to identify the moment the dog did the wrong thing. When that happens, just say your NRM and start over. There’s no need for an angry tone, and, please, no physical corrections. When the dog makes a mistake, it is just that: a mistake. Imagine if your teacher punished you every time you made a mistake; you probably wouldn’t want to learn from this person anymore, and rightly so!

The last handy word is a release word, telling Princess that she can stop lying down now. I use “OK.” Without this word, she won’t know for how long to lie there, and she will eventually get up on her own. It’s better for you so release with “OK” before that happens.

There are several strategies to replace counter-surfing with acceptable behavior.

Cues

When I was growing up, dogs went to “obedience school” and obeyed “commands.” The attitude toward the dog was, “Do it. And if you don’t, expect unpleasant consequences.” As times have changed and training has evolved, so has the lingo. Obedience and commands are out, and manners and cues are in. This shows the current direction of dog training, which is more about the dog being polite than being obedient, and we recognize that the dog certainly has a choice whether to obey our cues or not. The goal of positive dog training is to make the polite behavior—such as sitting, rather than jumping, to be petted by a stranger—the better choice in the dog’s mind. Sure, he can choose to be rude, but only being polite gets him what he wants, so it’s in his best interest to listen to your cue.

Cues reveal a great deal about the differences between humans and dogs. We humans talk a lot, and it’s quite a challenge to get us to stop. In BKLN Manners™ and other group classes I teach, I always remind participants to say the cue only once. And almost every participant breaks this rule again and again, not because they are bad at following instructions but because they are normal human beings who tend to repeat the same thing, louder and louder, until they are acknowledged. (For an enlightening comparison of human and dog behavior, I recommend Patricia McConnell’s The Other End of the Leash.) If you think about dogs, though, they generally don’t vocalize, excluding arousing or alarming events like a doorbell ringing or rowdy off-leash play. In general, their world is pretty quiet, and for us to train them effectively, we need to put our human tendencies aside and follow suit.

So, from now on, unless told otherwise, give the cue only once. Once! (There I go, repeating myself like a human.) Imagine if you say, “Sadie, sit. Sit. SIT!” Finally, she does, but what has the cue become? It’s become two cues that Sadie can ignore, and only the third time does she have to listen. Instead, say the cue once and then ensure that the dog is in a situation in which she will definitely sit. This will be outlined in the steps of later chapters.

If, while training something new, you say the cue (e.g, “Sit) and the dog doesn’t immediately respond, count to ten in your head. Dogs, especially puppies, take a little extra time to process what you’ve said. Give your dog the chance to respond to your first cue; most dogs do if you just give them sufficient time. If you completely lose his attention, or more than ten seconds has passed, then reevaluate what may have gone wrong and start over. The next time you ask for a Sit, create a situation in which you know he will sit, possibly by moving to a quieter area or using a tastier treat, so he can be successful with just one cue.

Four-for-Four

Let’s go back to the metaphor of taking a language class. Either as a child or an adult, you have probably learned a foreign language to some extent. In my case, I have been taking Japanese language classes for more than a decade so I can communicate better with my Japanese in-laws. One program I took was divided into twelve levels, but there was no exam at the end of each level to determine if the students really understood the material enough to move on to the next level. All of the students moved up to more difficult levels at the end of each semester, regardless of proficiency. Without an assessment to gauge each student’s comprehension, what happened was, by Level 5 or so, students started getting in over their heads, lost their motivation, and many ultimately dropped out. Having a background in education, I already knew that when the material got overwhelming, I would need to repeat a level. And I did, at Level 6 and then again at Level 10. Despite criticism from my classmates (“Why are you wasting your money to repeat old material?” “If you want to feel like the best student in the class, maybe you should retake Level 1, ha ha!”), it was repeating those levels that allowed me to really absorb the information I’d learned and smoothly progress to Level 12—while my snarky classmates gave up and dropped out, one by one.

The same concept holds true for dogs. When teaching a new behavior, we want to make sure that the dog fully understands the criteria for Level 1 before we move on to Level 2. I recommend practicing “four-for-four,” which involves working on a new behavior at Level 1 until you get it correct four times in a row. It might take only your first four responses to move up to the next level, or it might take several more repetitions until you can get four correct responses in a row. Regardless, four-for-four will tell you that your dog really gets it, at which point you can proceed to Level 2 and practice at that level until you get four correct responses in a row. This is how you prevent yourself from pushing the dog too far too fast, which would put him under the same stress as a Japanese language student who can’t keep up.

To illustrate, if you’re practicing Place with Distance from Chapter 3, which teaches the dog to go to his bed and remain there, you would start by getting four-for-four while you stand next to the bed. This means repeating the same cue from the same short distance as many times as needed until your dog correctly goes to his bed four times in a row. Once you have those four correct responses, take one small sidestep away from the bed and cue the dog to his “place.” Now you’re at a more difficult level because you’re farther from the bed, so you’ll need to practice at this distance as many times as needed until your dog gets four correct responses in a row. Once you have four-for-four at that distance, take another small step away, get another four-for-four, and so forth.

Four-for-four is intended to prevent you, the handler, from advancing levels too quickly, and it works well for the majority of dogs. I should mention, though, that not all dogs require four-for-four to achieve success at a particular level. In fact, a few dogs may actually get bored by the second or third correct response, and if the difficulty doesn’t increase, they will lose focus. It’s fine to modify your training plan for a dog who only needs two-for-two or three-for-three.