Kehinde Andrews, Dr. Peniel E. Joseph,

Erica Armstrong Dunbar

©2023 by Future Publishing Limited

Articles in this issue are translated or reproduced from

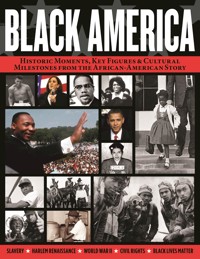

Black America

and are the copyright of or licensed to Future

Publishing Limited, a Future plc group company, UK 2022.

Used under license. All rights reserved. This version

published by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc.,

903 Square Street, Mount Joy, PA 17552.

For more information about the Future plc group, go to

http://www.futureplc.com.

e-ISBN: 978-1-6374-1254-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

To learn more about the other great books from Fox Chapel

Publishing, or to find a retailer near you, call toll-free

800-457-9112 or visit us at www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

We are always looking for talented authors.

To submit an idea, please send a brief inquiry to

bookazine series

Part of the

INTRODUCTION

The African-American story is undeniably one of

heartache, pain, and struggle. However, it’s also one

filled with resilience, creativity, innovation, and hope.

In Black America we aim to tell that story through

a timeline of the historic events, significant figures,

and cultural milestones that have come to represent

the Black American experience. Over the pages you’ll

discover fascinating features on the events of the Civil

Rights Movement, the birth of soul music, African-

American involvement in World War II, how Black

athletes broke down racial barriers in US sport, the

origins of the BLM movement, and much more.

CONTENTS

8

FIRST BLACK AMERICANS

10

AMERICA’S CENTURIES OF SLAVERY

14

PHILLIS WHEATLEY

16

UNCLE TOM’S CABIN

18

NAT TURNER’S REBELLION

22

FREDERICK DOUGLASS: SLAVE TO STATESMAN

28

HARRIET TUBMAN: SLAVE, SPY, SUFFRAGETTE

36

AMERICAN CIVIL WAR

38

EMANCIPATION

40

BLACK COWBOYS

42

RECONSTRUCTION

44

JIM CROW LAWS

46

WASHINGTON & DU BOIS:

THE POWER OF EDUCATION

50

THE NAACP IS FOUNDED

52

HARLEM RENAISSANCE

56

TULSA RACE MASSACRE

58

JESSE OWENS

60

THE BLACK EXPERIENCE IN

WORLD WAR II

64

LEVELING THE PLAYING FIELD IN

US SPORT

70

BROWN V BOARD OF EDUCATION

72

EMMETT TILL

74

ROSA PARKS: TIRED OF GIVING IN

78

LITTLE ROCK NINE

80

AMERICA GOT SOUL

86

SIT-INS AND FREEDOM RIDES

88

BIRMINGHAM CAMPAIGN

8

64

80

60

74

© Alamy, Getty Images, Wikimedia Commons

92

‘I HAVE A DREAM’

100

BIRMINGHAM CHURCH BOMBING

102

MISSISSIPPI MURDERS

104

CIVIL RIGHTS ACT

106

SELMA TO MONTGOMERY MARCH

110

MALCOLM VS MARTIN

120

THE BLACK PANTHERS

126

BLACK POWER SALUTE

128

I KNOW WHY THE CAGED BIRD SINGS

130

JIMI HENDRIX AT WOODSTOCK

132

SHIRLEY CHISHOLM RUNS

FOR PRESIDENT

134

RUMBLE IN THE JUNGLE

136

RISE OF HIP HOP

142

THE OPRAH WINFREY SHOW DEBUTS

144

RODNEY KING AND THE LA RIOTS

146

BARACK OBAMA: FIRST

BLACK PRESIDENT

150

BLM: THE NEW CIVIL RIGHTS

MOVEMENT

156

THE GEORGE FLOYD PROTESTS

158

KAMALA HARRIS

146

110

150

136

A census from Virginia shows the first documented

African woman, Angela, to arrive at the colony

A woodcut showing enslaved

Africans being introduced to

Jamestown, Virginia, in the 1600s

© Alamy, Getty

8

FIRST BLACK AMERICANS

The importation of Black Africans was seen as the ideal solution

to an emerging labor problem in North America. White settlers

and Native Americans were rapidly dying, so Africans who were

used to a similar climate and seemingly resistant to many of the

diseases killing the indigenous population were brought in

The story of Black America goes back 500

years, when the first captured Africans

were brought to the New World; the

original members of a burgeoning,

resilient community

FIRST BLACK

AMERICANS

T

he first known Africans to set foot on North American

soil were a group of enslaved people brought by the

Spanish to present-day South Carolina from Santo

Domingo (Haiti) in 1526 to found a new colony. They

were brought as part of the expeditions that followed

Christopher Columbus’s first voyage, but following

a struggle for control, they set fire to the houses and

fled to freedom among nearby Native Americans. The Spanish too

quickly fled back to Santo Domingo and the precedent had been set

for a long history of resistance and rebellion against oppression.

The first surviving Africans in English America were the “20

and odd Negroes,” Angolans originally captured by the Portuguese,

who came to Jamestown, Virginia, on the famous voyage of 1619 as

indentured servants. In fact, most early Africans in the Americas

were not actually enslaved; they were servants made to work

unpaid for seven years to pay off their passage and upkeep. They

were treated brutally but eventually were free to go with a release

payment and provision to start a new life. Indentureship was not

lifelong or hereditary like slavery. Thus, in the early days, a lively

free Black population owned farms, grew wealthy, and made major

contributions to the young new nation.

Forging a life for these early African Americans was tough, but

there is evidence of surviving, flourishing African art, music,

religious and culinary practices, trade and financial systems, and

languages. They came with knowledge of agricultural techniques,

medicine and technology that fundamentally shaped America and

the crops and food staples still in place today. Many were urban

Angolans who were highly educated and cosmopolitan. They

demanded freedom, shaping and contributing to American ideals.

The first instance of lifetime slavery wasn’t recorded until 1640,

when an indentured servant, John Punch, was sentenced to lifetime

servitude for running away. From the 1660s, racial, inherited

slavery became more widespread, and in 1699, Virginia deported

all free Blacks, with those remaining enslaved. Though Black

Americans were an important free community that contributed

to the beginnings of the US, as racism evolved, things began

to change. Between 1690 and 1710, the population of Africans

in British colonies tripled from 16,700 to 44,900 through the

slave trade. Just before the Revolutionary War, 22 percent of the

American population was Black, and mostly held in bondage.

FIRST BLACK AMERICANS

9

A

merica didn’t invent slavery,

but it embraced it with horrible

enthusiasm. Slaves were the

backbone of the American economy.

Between 1790 and 1860 the

harvesting of cotton in the Southern

states grew from a thousand tons

a year to a million, with slaves the crucial labor

force needed to bring in those crops. In 1790

there were half a million slaves in the South.

There were four million by 1860. The system was

backed by legislation, the courts, the military, and

the government. The importation of slaves

actually became illegal in 1808, but the

law went unenforced, meaning that

hundreds of thousands of slaves

continued to be brought into the

country, usually from Central

and Western Africa. The system

was so entrenched that only

the Civil War could bring it to

an end.

Slaves had a low life

expectancy and were treated

more like cattle than human beings;

they were sold at auctions, where their

physical attributes and talents were talked up

as their most marketable qualities. Slave owners

would often break up families, selling husbands

or wives, or their children. This was often a

deliberate policy to subdue the slaves’ spirits –

after all, a slave without a family was thought to

have less will to resist. There were also sometimes

economic reasons: at one point there was such a

surplus of slave labor in the Upper South that a

forced migration of more than a million slaves

to the Deep South was implemented. Through

all of this, slaves held on to their humanity. Torn

from their families, they formed deep kinships

with their companions on the plantations. Music,

dancing, art, and religion all remained important

– although the latter could be used against the

slaves. Black preachers were also sometimes

employed to preach in ways that kept the slaves

in line.

Whippings and other brutal punishments were

not only widespread but normal. Slave revolts

were unusual since they were swiftly put down

with military force. Escape was more common,

although risky. Successful runaways made new

lives in Canada, Mexico, or the North, but getting

caught in the process of escape meant getting

torn apart by dogs, or shot. The Fugitive Slave

Act was passed in 1850 to make it easier

for slave owners to reclaim their

‘property’ south of the border in

Mexico, and there were laws to

dissuade White people from

giving aid to escaped slaves.

Poor, uneducated White people

were employed as overseers of

Black labor, entrenching White

racism in the South for decades

to come.

Unsurprisingly there were

uprisings, although most were swiftly

crushed. One of the most famous was led

by Nat Turner on August 21, 1831. Turner and his

band of brothers were ultimately unsuccessful,

and security in the South became even tighter

as a result of their rebellion. But the voices of

abolitionists were getting louder. In 1853, John

Brown (a White man) hatched a plan to seize the

federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and

spark a slave revolt throughout the South. Local

militia, plus hundreds of marines under the

command of General Robert E. Lee, put down

the insurgency (Brown was hanged), but it was

clear that the issue was far from concluded. Still,

as late as 1857 the Supreme Court ruled that

Dred Scott could not sue for his freedom because

he was property and not legally a person.

AMERICA’S CENTURIES

OF SLAVERY

America was founded on the principle of

liberty and justice for all, but it wasn’t the

land of the free for everybody

Slaves

in Kentucky

in the 1860s were

valued between $40

to $400 each. Strong

males in their 20s

were highly

prized

Robert E. Lee, the commander of the defeated

Confederate States Army

10

AMERICA’S CENTURIES OF SLAVERY

Slave market, Richmond, Virginia, 1853

AMERICA’S CENTURIES OF SLAVERY

11

NAT TURNER’S

SLAVE REBELLION

Nat Turner lived his entire life in

Southampton County, Virginia.

Intelligent and religiously devout, he

could read and write at an early age

and, by his twenties, he was preaching

services to his fellow slaves. He became known locally as ‘The Prophet’ for that reason, and

because of the spiritual visions he claimed to have. One such vision in 1828, when Turner was

28, inspired him to begin planning a violent uprising, which finally took place in August 1831.

Turner interpreted a solar eclipse on the 13th of the month as a sign from God for the slaves

to begin the fight back against their oppression.

Having banded together a force of about 70 men, Turner began traveling from house

to house in Southampton County, freeing slaves and killing their White ‘masters’. The

murder was indiscriminate, including women and children, and Turner and his rebels were

responsible for at least 60 deaths before they were stopped, finally overwhelmed by a White

militia with more than double the manpower of the insurrectionists. The uprising had lasted

two days.

Over 50 Black men and women were executed in the aftermath on charges of murder,

conspiracy, and treason. Turner himself was hanged on November 11, and his corpse flayed,

decapitated, and dismembered. The following year in Virginia, it became illegal for slaves to

be educated, or to hold religious meetings in the absence of a White minister.

All of the above took place under the

presidency of Andrew Jackson. Abraham

Lincoln replaced him in 1860, with discomfort

about slavery part of his platform (though he

wasn’t strictly abolitionist). The secession from

the Union of 11 pro-slavery Confederate states

reliant on slave labor for the plantation system

took place the same year. Lincoln began leaning

politically slightly further to the left thanks to

the continuing pressure of abolitionists.

Congress passed the Emancipation

Proclamation, declaring slaves on all Confederate

territory immediately free, in 1862, although the

North was hardly a utopia of equality: citizens

were still allowed to own slaves as long as they

were loyal to the United States. Lincoln argued

passionately about the humanitarian wrongness

of slavery (although he was careful not to

advocate any sort of social or political equality

between White and Black). By the summer

of 1864, buoyed by the Emancipation

Proclamation, anti-slavery petitioners

had sent 400,000 signatures to

Congress demanding slavery

be abolished. The Senate and

the House of Representatives

signed off on the Thirteenth

Amendment to the US

Constitution. Slavery was

legally over.

While the government could

legislate against slavery, however, it

could hardly legislate against racism.

With the Civil War now regarded to a great

extent as one of Black liberation, the resentment

of White people drafted to fight in it became

dangerously volatile (especially since the draftees

were usually poor – Whites with money could

buy their way out of fighting). There were draft

riots, in which cities were overrun with anti-

Black violence. But the African Americans in the

South now found themselves with unexpected

power, since the Confederacy, perversely, needed

them to fight the Union. It could either free its

slaves, enlist them in its army and use them to

fight in the war – thereby negating the point

of much of the conflict – or it could refuse and

watch its enslaved workforce down tools and

defect to the Union Army. Congress granted

equal pay to Black and White soldiers in April

1864. A year later, with the Confederate troops

depleted and demoralized, the war was finally

over. Lee surrendered to Grant.

Despite the new rights of freed African

Americans to vote, be educated, and serve

politically, however, White American society,

especially in the South, remained aggressively

opposed to equal rights for Black people.

President Andrew Johnson, who took office after

Lincoln’s assassination, was firmly on the side of

the Whites on these issues, refusing legislation

leaning towards racial equality. Slavery may have

been over, and Black children attending school,

but former slaves found themselves living and

Slaves were

the most valuable

asset of the American

economy, worth

roughly $3 billion in

1860

Union Army general Ulysses

S. Grant became president in

1869 and worked to protect the

civil rights of former slaves

Nat Turner and companions depicted in 1831

12

AMERICA’S CENTURIES OF SLAVERY

THE INCREDIBLE

HARRIET TUBMAN

Harriet Tubman was born into slavery

in 1822 in Maryland. She was violently

mistreated throughout her young life –

at one point sustaining a serious head

wound from a thrown metal weight, the

after-effects of which remained with her

for the rest of her life. But that life was a

long and eventful one.

Aged 27, she escaped the plantation she

was indentured on, making use of the

‘Underground Railroad’, a network of safe

houses and abolitionist activists dedicated

to helping slaves gain their freedom. She

subsequently became prolifically active in

the Railroad herself, undertaking daring

missions back into Maryland to help

rescue other slaves. She was so successful

at it that the abolitionist William Lloyd

Garrison dubbed her ‘Moses’.

Tubman was a devout Christian

who absolutely abhorred violence, but

nevertheless later became a ‘General’ in

John Brown’s (ultimately unsuccessful)

On

February 24,

2007, Virginia

became the first state

to acknowledge and

publicly apologize

for its history of

slavery

insurrectionist movement. When the Civil

War broke out in 1861, she identified the

Unionist cause as the one most likely to

bring about an end to slavery, and worked

as a scout and a spy in Confederate territory,

helping to free slaves in their hundreds.

Well into her seventies, she became active

in the fight for women’s suffrage. She died

from pneumonia, aged 91, in 1913, in a rest

home named in her honor.

working on the same plantations, unable,

both financially and legally, to buy or rent

their own land, and forced to work under

strict labor contracts with prison sentences the

punishment for breaking them. These were

the Black Codes that formed the antecedents

of the ‘Jim Crow’ segregationist laws of the

20th century.

Black votes played a huge part in the

election of President Ulysses S. Grant in 1869,

and with Johnson out of the picture, some

societal progress was made, with equality laws

passed and constitutional amendments put

forward.

But whenever the cause of African-American

rights advanced, there was White resistance

to meet it. Racist groups like the Ku Klux

Klan sprang up to terrorize Black people and

keep them oppressed, and as those groups

gained more and more members, politicians

desperate for votes were forced to pander

to them. The African-American blacksmith

Charles Caldwell shot a White attacker in self-

defense and was acquitted of murder at the

subsequent trial. He was the first Black man

ever to kill a White man in Mississippi and

go free. Not long afterwards, however, he was

murdered by a White gang. The White South

was going to continue to make its own justice,

regardless of laws that suggested otherwise.

“WHITE AMERICAN SOCIETY REMAINED

AGGRESSIVELY OPPOSED TO EQUAL RIGHTS”

Slaves on the plantation of the Confederate

general Thomas F. Drayton, South Carolina, 1862

Harriet Tubman, photographed in 1900

© Getty

AMERICA’S CENTURIES OF SLAVERY

13

A statue of Phillis Wheatley is part of the Boston Women’s

Memorial in Commonwealth Avenue Mall, Boston

Phillis Wheatley was the first African-

American woman to publish a book of

poetry, and is widely considered

fundamental to the genre of African-

American literature

PHILLIS

WHEATLEY

T

here is no record of what the little girl that would later

become Phillis Wheatley was doing on the day she

was stolen from her home, somewhere in West Africa,

around 1760. After surviving the horrifying journey

across the Atlantic, at seven years old, she was enslaved

by John Wheatley and his wife, Susanna, in Boston,

Massachusetts. They named her after the ship she was

transported on, and after deciding that she was more intelligent

than the rest of those they enslaved, they separated and educated

her. Phillis excelled in Latin and Greek, and began writing poetry.

In 1770, the publication of Phillis’s poetic tribute to an evangelist

preacher gained her some notoriety. However, many White

academics found it difficult to believe that an enslaved African

woman could possibly be writing poetry, so in 1772, she was

‘examined’ by a group of White men who eventually wrote a letter

to confirm her authorship.

Accompanied by her captor’s son, Nathaniel Wheatley, Phillis

traveled to London in 1773, aged 20. There, she published a

collection called

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral

, which

was well received. Phillis’s poetry rarely engaged with her identity

as an enslaved Black person – an exception being

On Being Brought

from Africa to America

, which went on to become one of her most

well-known works.

Phillis cut her trip short and returned to Boston when

Susanna Wheatley became ill. A month later, she was freed.

After Susanna’s death in 1774, Phillis became more vocal about

her views on slavery. In a published letter to a Native American

minister, she described enslavers as “modern Egyptians,”

drawing parallels between Africans and the Hebrews of the

Old Testament. In 1778, Phillis married John Peters, a free Black

man from Boston. The couple had three children together,

none surviving infancy. At some point after 1780, John was

prosecuted for debt and the couple fled Boston. On returning,

he was incarcerated and Phillis got work as a scrubwoman in a

boardhouse. She died due to complications from childbirth in

December 1784, aged 31.

Following his wife’s death, John kept trying to publish her second

book. Some of the poems from this volume were later recovered

and released in collections. Regardless, her work was frequently

cited by abolitionists, and used to promote equal education.

14

PHILLIS WHEATLEY

A plaque to honor Phillis Wheatley,

at 9 Aldgate High Street, London

© Getty, WikimediaCommons/Spudgun67

PHILLIS WHEATLEY

15

Harriet Beecher Stowe published over 30

books, but is known around the world for

one in particular: the bestselling anti-

enslavement novel

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

,

published in 1852

UNCLE

TOM’S CABIN

T

he book opens on the Shelby plantation, Kentucky (in

around 1850), introducing two enslaved people – Uncle

Tom and a boy called Harry – about to be sold. The story

then splits into two plot lines, one focusing on Uncle

Tom and the other on Eliza, Harry’s mother.

While being transported to an auction by boat,

Tom saves the life of a young White girl called Eva,

and is purchased by her father. Later, a violent White enslaver

called Simon Legree becomes Tom’s new captor after Eva and her

father both die. Legree finds any excuse he can to terrorize Tom,

determined to crush his faith in God. Throughout it all, Tom’s

character remains dignified, noble, and resolute in his faith.

Meanwhile, Eliza and Harry make a dramatic escape and eventually

reunite with Harry’s father and journey north to Canada.

Stowe’s inspiration came from several places, including her

immersion in abolitionist writings, her visit to a Kentucky

plantation as a young adult, and her Christian faith (she sometimes

claimed it was “the result of a vision from God”). She also searched

anti-enslavement newspapers for first-hand accounts and invited

others to send her information.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

was an instant bestseller. In the US, it sold

10,000 copies in its first week and 300,000 in the first year. It was

the bestselling novel of the 19th century.

Stowe became a leading voice in the anti-slavery movement,

despite her use of derogatory language and offensive racial

stereotypes in

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

that exposed her many

misconceptions about Black people. People from the 19th century

up to the present day have debated whether Stowe had the right

to speak for enslaved African people, acknowledging that her

whiteness meant she had a wider reach than a Black author would

have had at the time.

In the build-up to the American Civil War, Stowe’s novel

dramatically shifted public opinion about the enslavement of

African people. During the 20th century, however, it was heavily

criticized by many Black writers, including James Baldwin in his

1949 essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel.” The term ‘Uncle Tom’ has

since become an insult, used to describe a Black person filled with

self-hatred who is somehow complicit with white supremacy. The

development of the insult was likely inspired by the early theatrical

adaptations of the novel, which often distorted Uncle Tom and

changed the ending to make more comfortable viewing for White

audiences of the time.

16

UNCLE TOM’S CABIN

This quarter-plate daguerreotype of Harriet

Beecher Stowe was probably made around the time

of the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852)

© Getty

This illustration from an early-20th century

edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published

by Frederick Warne, London, shows Tom

reading his Bible to women in the hut

UNCLE TOM’S CABIN

17

I

n 1831, a group of enslaved people in

Virginia launched a 36-hour rampage

that left almost 60 White people dead.

Although the White establishment

was desperate to paint the incident

as an anomalous plot organized by a

bloodthirsty barbarian, the reality spoke

for itself. It was the natural consequence of the

brutal system of slavery so deeply threaded into

the veins of Southern antebellum society.

At the turn of the 19th century, the invention

of the cotton gin had completely transformed

the South. The American cotton industry,

centered in the Deep South, exploded, becoming

the country’s leading export as it fought its

way towards international trading supremacy.

With profits soaring, so too did demand for

slaves, and when the international slave trade

was abolished in 1808, Upper South states like

Virginia gained a stranglehold over the country’s

domestic slave market.

By 1820, two-fifths of Virginia’s one million

population were enslaved people, with 1.5

million more scattered across the South. Slaves

were the legal property of their owners, who

enforced strict control over how they lived,

dishing out cruel punishments for those who

broke the rules. For the enslaved, simply holding

social meetings and church services were great

acts of rebellion.

While slave owners and overseers were

responsible for supervising slaves during the

day, Virginia’s 101,488 militia members took care

of the night patrols. One Southampton County

resident, Allen Crawford, recalled: “Patrollers

would whip you if they caught you without a

pass.”

White slave owners used systematic brutality

to keep Black slaves in perpetual terror. One

escapee, Julian Wright, had a chain clamped

around her leg so tightly it became infected,

stripping all the flesh from the bone. When a

Virginian slave, Lucy, could not work the fields

because she was in labor, her overseer whipped

her so severely she later died – her daughter

born with lash marks on her back. Another,

Fannie Berry, recalled how after being severely

whipped, a fellow slave remarked, “Fannie, I

don’ had my las’ whippin’. I gwine to God,”

before killing herself.

As a natural reaction to this oppression, many

enslaved people developed their own system of

evasion – keeping their meetings secret while

sending lookouts to track patrols and, if need be,

lead them into dead ends or strategically placed

brambles. One group kept a pile of hot ash and

coals ready during meetings, hurling it when the

patrol arrived.

In the 1820s, the Deep South’s cotton supply

grew so large the global price dropped by 55

percent. The resultant depression clogged up

the domestic slave market, leaving Virginia

with a massive slave population. In 1829,

Virginia governor John Floyd warned the

legislature about the “spirit of dissatisfaction and

insubordination” among the country’s slaves.

While this received little attention, a minor

media frenzy accompanied the acquittal of a

Black man, Jasper Ellis, accused of “promoting

an insurrection of the slaves.”

This “spirit of dissatisfaction” was only

amplified when the Virginia Constitutional

SLAVE UPRISING:

THE NAT TURNER

REBELLION

Often attributed to its leader, Nat Turner, the

Southampton Rebellion was a natural consequence of

the brutal Southern slave system

18

SLAVE UPRISING: THE NAT TURNER REBELLION

© Alamy / Getty Images

This 1863 engraving depicts Nat

Turner and some of his fellow rebels

Convention of 1829-30 maintained a

commitment to slavery. Ironically, the delegate

Charles Ingersoll, who argued that “no one

man comes in the world with a mark on him to

designate him as possessing superior rights to

any other man” was a staunch anti-abolitionist.

Although the country’s leading abolitionists

met at the Negro Conventions of 1830 and 1831

to propose creating a college for Black people,

the Virginia legislature only further suppressed

and disenfranchised slaves. It banned free Black

people from congregating for the purposes

of education, marrying Whites, or living with

slaves, and sold all Black criminals into slavery.

It was in this climate, amidst the hot and

sticky swamps and forests of Southampton, torn

between endless brutality and fleeting promise,

that Nat Turner fomented his violent rebellion.

Born a Southampton slave in 1800, rebellion

ran in Turner’s blood: his father had run away,

successfully escaping all the way to Liberia.

Turner began having religious experiences as

a young boy and, having learned to read and

write, grew up believing himself to be a prophet

In the early 19th century the Deep

South’s cotton industry exploded,

creating an unprecedented demand

for enslaved workers

SLAVE UPRISING: THE NAT TURNER REBELLION

19

African-American slaves who met to worship

were risking torture and death if caught

– interpreting coded messages from God in

visions and signs in nature. These visions

culminated in “a loud noise in the heavens”, a

solar eclipse and an atmospheric phenomenon

that, by August 1831, convinced him that he

must rise up in violent revolt.

On August 21, after a night spent dining on

a stolen pig, Turner led a group of followers to

his master’s house, where they butchered the

entire family with hatchets – even a sleeping

infant. During the following day-and-a-half the

rebels moved from plantation to plantation,

freeing slaves, taking weapons and murdering

every White person in their path. At their peak

the rebels numbered around 50, killing almost

60 people before being dispersed by the local

militia 36 hours into their rampage. While most

of his accomplices were arrested and executed,

Turner remained on the run.

Although the rebellion lasted less than two

days, it sent a tidal wave of terror and hysteria

across the South. Plantations were abandoned as

owners whisked their families away to hideouts,

anticipating further carnage. Rumors spread of

further insurrections, such as fictitious stories

of maids caught plotting to kill children, Black

men caught with huge arsenals of guns, and

Turner sightings across the country. When

a second rebellion in neighboring North

Carolina involving 25 slaves was betrayed by

an African-American freedman, the paranoia

reached frenzied heights. In the Virginia town

of Petersburg, when a report of a 500-strong

slave rebellion was proved to be a false alarm,

an English bookseller remarked that Black

people should be emancipated. He was stripped,

lashed, and chased out of town.

Amidst the panic and hysteria, White

volunteers rode across the South, torturing,

burning, and murdering

any African Americans they

came across. Newspapers ran

stories on prolific killers, one

of whom boasted of lynching

15 Black people alone. In

Georgia, slaves were tied to

trees en masse and hacked to

death. One enslaved person

who had saved his master

from the rebels was gunned

down by his owner for

refusing to help track them

down.

After six weeks, Turner

was discovered by chance in

Dismal Swamp by a hunter.

The last rebel to be caught,

he was interviewed in jail

by a wealthy Southampton lawyer and slave

owner, Thomas Gray. The subsequent essay,

“The Confessions of Nat Turner”, was used as

evidence against him during his trial. Less than

a fortnight after his capture he was found guilty

and hanged before a large crowd. His corpse

was skinned and his flesh turned into souvenirs

and grease, his bones handed out as keepsakes.

Though Turner was dead, his belief that other

slaves would rise up to claim their rightful

freedom was shared by

the White establishment,

who desperately sought

to contain White fear and

mitigate slaves’ expectations.

Virginia’s governor John

Floyd delivered a paranoid

address to the legislature,

stressing the need to silence

Black preachers and shut

down freedom of movement.

Even though free African

Americans had nothing to do

with the revolt, the governor

saw them as the driving

force behind the emerging

abolition movement.

Turner’s revolt brought

the issue of slavery to

the forefront, and before long the Virginia

legislature was inundated with petitions and

requests ranging from the emancipation of

slaves to the deportation of free Black people to

Africa. On January 25, 1832, after fierce debate,

the legislature’s special committee concluded

“FOR SLAVES,

SIMPLY HOLDING

SOCIAL MEETINGS

AND CHURCH

SERVICES

CONSTITUTED

GREAT ACTS OF

REBELLION”

20

SLAVE UPRISING: THE NAT TURNER REBELLION

that while most of its members believed slavery

was evil, none were willing to pay the price of

abolishing it. The committee chairman, William

Brodnax, lamented the result but expressed

faith that slavery would someday be eradicated

gradually.

With emancipation off the cards and the bill

to deport Black people to Africa postponed

indefinitely by the Senate, Virginia and its

neighboring states introduced a series of

laws designed to further suppress Black

people’s rights. These included banning

African Americans from meeting in groups

after 10 p.m., preaching without a licence,

immigrating, owning arms, attending their

own religious services, learning to read, selling

food or tobacco, and buying alcoholic spirits.

While the Southampton Rebellion did not

inspire the wider revolution Turner had hoped

it would, it did force Southern slave states to

recognize that slavery was an evil that must one

day be abolished. It was not Turner’s Rebellion,

but a reflex reaction to the systemized barbarity

of slavery. The event left a gaping wound in the

legitimacy of slavery that would be torn wide

open just decades later as the country erupted

into Civil War, marking the end of American

slavery and the beginning of a new chapter in

the fight for civil liberty.

While some historians have identified records of more

than 300 slave revolts in the US alone, the country’s

first all-Black rebellion took place in Virginia in 1687

with the Westmoreland Slave Plot. Half-a-century

later, in 1739, a slave named Jemmy led 100 Angolan

slaves on a killing spree across the Stono River region

towards St. Augustine, Florida, where they would be

free under Spanish law. They fought for a week before

being suppressed by the English, inspiring a series of

subsequent revolts.

Two years later, when a series of fires broke out

across New York and Long Island, it was blamed on a

joint slave-Catholic conspiracy, sparking off a witch-

hunt. Despite little evidence, up to 40 enslaved people

were hanged or burned at the stake, alongside four

Whites. Many more were exiled.

In 1791 the slaves of Saint-Domingue, the world’s

most profitable slave colony, rose up in revolt against

their French colonial masters. Thirteen years later

they emerged victorious, founding the independent

nation of Haiti. Among those who were inspired by the

Haitian Revolution was a literate enslaved blacksmith

known today as Gabriel Prosser who, in 1800, planned

to raise 1,000 slaves in revolt beneath a banner of

‘Death or Liberty’. But he was betrayed and executed

alongside 25 Black men.

Just 11 years later another slave inspired by the

Haitian Revolution, Charles Deslondes, organized a

rebellion along Louisiana’s German Coast with the aim

of capturing New Orleans. After swelling to roughly 125

men, the rebels were only defeated after two days of

bitter fighting when they ran out of ammunition. After

the battle, 100 enslaved people were executed and their

severed heads placed along the road to New Orleans.

On July 3, 1859, White abolitionist John Brown

and his two sons led a raid on Harpers Ferry,

Virginia, hoping to instigate a slave rebellion. Despite

successfully liberating several slaves, they were

eventually put down by local militia and Brown was

hanged for treason.

The Southampton Rebellion was one of many slave revolts

inspired by the successful Haitian slave revolution

The Southampton Rebellion is often

considered the most ‘successful’ revolt, but it

wasn’t the first or even the largest

A HISTORY OF

AMERICAN SLAVE REVOLTS

© Alamy / Getty

The violent events of August 1831 shocked Virginia’s

White establishment to its core, forcing it to

re-evaluate its commitment to slavery

During the six weeks Nat

Turner remained on the run,

the South was swept up in

violent anti-Black hysteria

SLAVE UPRISING: THE NAT TURNER REBELLION

21

F

rederick Bailey was most likely born

in February 1818 (although there are

no records to prove the exact date)

in his grandmother’s slave cabin in

Talbot County, Maryland. He was

probably mixed race: African, Native

American, and European, as it’s likely

that his father was also his master. His mother

was sent away to another plantation when he was

a baby, and he saw her only a handful of times in

the dark of night when she would walk 12 miles

to see him. She died when he was seven.

Frederick was moved around and loaned

out to different families and households

throughout his childhood. He spent time on

plantations and in the city of Baltimore, a

place he described as much more benevolent

towards enslaved people, where they had

more freedom and better treatment than on

plantations. Indeed, Baltimore was one of

the most bustling harbor cities in America, a

meeting place of people and ideas of all kinds

from all around the world; a place in which

dreams and visions of freedom could easily

be fostered.

One mistress, Sophia Auld, took a great

interest in the 12 year old, teaching him the

alphabet. But her husband Hugh greatly

disapproved of teaching slaves to read and

write, believing it would equip them to access

ideas and aspirations beyond their station.

It would make them rebellious. Eventually,

Sophia came to agree with Hugh’s disapproval

and herself believe that teaching slaves to read

was wrong. She ceased her lessons and hid his

reading materials, snatching newspapers and

books from the enslaved boy’s hands when he

was caught with them.

But Frederick was shrewd and continued to

find ways to learn, trading bread with street

children for reading lessons. He learned to

buy knowledge and words from a young age.

The more he read, the more he gained the

language and tools to question and condemn

slavery, developing his sense of Black identity

and personhood for himself. When he was

hired back out to a plantation owned by

William Freeland, Frederick set up a secret

Sunday school where around 40 slaves would

gather and learn to read the New Testament.

FREDERICK

DOUGLASS:

SLAVE TO

STATESMAN

Discover the remarkable rise of an agitator,

reformer, orator, writer, and artist

22

FREDERICK DOUGLASS: SLAVE TO STATESMAN

© Alamy / Signature source: wiki/archive.org

FREDERICK DOUGLASS: SLAVE TO STATESMAN

23

Surrounding plantation owners gradually came

to know of these clandestine meetings and one

day descended on the group armed with stones

and clubs, permanently dispersing the school.

Not long after, Frederick was sent

to work for Edward Covey, a

poor farmer with a dreadful

reputation as a ‘slave breaker’.

He was sent to be broken,

to have his rebellious

spirit crushed and be

transformed into a docile,

obedient worker. He faced

frequent whippings,

and at just 16 he resolved

to fight back, physically

asserting his strength over

Covey. Frederick tried to

escape once but failed.

That was before he met

Anna Murray in 1837.

Anna was a free Black woman in

Baltimore who was five years older

than him. The pair quickly fell in love and

she encouraged him continuously to escape

and find freedom, helping him to realize

that freedom was truly within his grasp. The

following year, in 1838, aged 20, Frederick made

his break from the shackles of slavery.

He made the passage from slave state to free

state in under 24 hours, boarding northbound

trains, ferries, and steamboats until he made it

to Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, then a Quaker

city with a strong anti-slavery sentiment. He

then traveled to New York disguised in

a sailor’s uniform. He faced many

close shaves, even catching the

eye of a worker whom he

knew, and who mercifully

remained silent about

seeing him. On setting foot

in the north, Frederick

was a new man, master