Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Brandon

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In this collection, one of Ireland's best-known political figures brings us new and selected stories of politics, of family, of love and of friendship. These are portraits of Ireland, and especially Belfast, old and new, in times of struggle and in times of peace, showing how our past is always part of our present. Sometimes sad, sometimes funny, always moving, these are stories of ordinary people captured with wit, with heart and with understanding. Introduction by Timothy O'Grady.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 369

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

GERRY ADAMS

BLACK MOUNTAIN

5

For Richard

Contents

Foreword

I first met Gerry Adams in 1982. I was in West Belfast to talk about a book of mine, staying in what might be called a political house. One mid-morning he passed into its living room – familiar from media images, professorial in sweater and with pipe, a touch shy, perhaps, but carrying an authority I had only very rarely seen – and then passed silently out. I hadn’t expected it. He seemed an apparition. But a little later someone asked on his behalf if he might be given a copy of my book. Funds were short. I said I’d trade one for his Falls Memories, his first.

And so we started exchanging books by post or by hand over three decades, but though writing is all I professionally do, and though he was leading a movement through war, peace negotiations and the implementation of the eventual agreement, he soon outpaced me. I am currently at seven, this is his eighteenth, and the number does not include seven biographical pamphlets commemorating people he admires and a small book of poems in Irish and English. Many, as might be expected, are acts of persuasion. Others, perhaps less expected, are acts of the imagination, like the one you are holding. 10

One of the poems, ‘The Second Chance’, addressed to his wife, speaks to the interface of the personal and the political:

Our eldest lad Gearóid

Was four and a half

Before we first walked together

Through the Royal hills of Meath.

Miles away from the barbed wire

And the Visiting Boxes of Long Kesh.

Hunting monsters in Aughyneill.

Over forty years later Gearóid and

Róisín’s oldest lad Ruadan arrived

In the foot steps of his three sisters.

To give me back the four and a half years

That his Daddy and I never had.

Without the barbed wire

And the Visiting Boxes of Long Kesh.

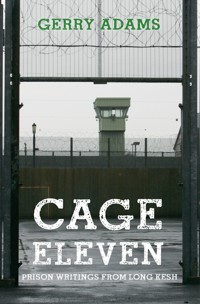

His first short pieces were about life within that barbed wire when he was an internee. They were smuggled out and published under the name ‘Brownie’ in Republican News and later collected in Cage Eleven (1990). ‘The Five Sorrowful Mysteries weeps quietly in the toilet,’ he writes of his comrades. 11

Crazy Joe, in the depths of a big D since Scobie left him, stares dejectedly at the blank TV screen and worries about his nose. The Hurdy Gurdy Man polishes his boots, again. Cleaky polishes the top of his head, again … Surely-to-God is making his nineteenth miniature piano … Guts Donnelly writes to his wife. On the next bed Twinkle Higgins writes to somebody else’s wife … Che O’Hara writes to Downing Street demanding his release and a British withdrawal from Ireland. It is Christmas week in the middle hut.

There are archivable, consonant-rich Belfast words such as glyp, latchico, sleekily, stumer and skite. The pieces are warm, witty, self-effacing, quick to bring a character to life, and written with a natural ease any writer might covet.

It was his fifth book. Six years later came his ninth, an autobiography, Before the Dawn. I was living in London at the time, just thirty metres from the pied-à-terre of former Northern Ireland Secretary Douglas Hurd. He had a twenty-four-hour two-man police guard when in residence. One hot summer afternoon while I was disassembling a bench in front of my house one of the policemen walked over. Perhaps he was bored. He offered some advice about the bench. He asked me what I did. It turned out he’d read something of mine in a magazine. He asked then if he could use my bathroom. He was gone a long time. I went on with the bench. He tipped his hat as he walked past me on his way back to his post. When I later went upstairs I saw that I’d left 12Before the Dawn, face up, a large photograph of the author on the cover and signed on the title page ‘Do Timothy, le buíochas, Gerry Adams, London, September ’96’, on a little table beside the toilet on which the policeman had been sitting. Perhaps a new file was opened somewhere, or an old one added to, as a result of the exchanging of books.

Writers often speak of having to do it. They are it, their identity depends on it. Ideas take them, seem necessary to them and, they hope, to the universe. They marinate them, go for walks with them, stare at walls thinking of them, wake in the night, feed them as birds do their young. These are not options open to him. Some time when he was a teenaged barman in the Shankill Road and the demand for civil rights was rising, he took a step away from his personal life and into history, along with thousands of others of his generation. He wrote, and writes, on the run, even if no longer from soldiers, in cars or planes or short slots in evenings after a long day. No time to marinate. Yet it calls him, and has done throughout his adult life. When I asked him what it meant to him he said he found it therapeutic. Some of the writers described above might wonder how an activity which has driven practitioners beyond neurosis could in itself be calming or curative, but for him it is, perhaps, the time alone, the relief for the intellect from strategising, the fleeting connection with subtle human feeling instead of the grind of political combat.

But it may too be a matter of the times he was in. Oppression 13 and the struggle against it often convert into paint on walls or canvas, ink on paper, whether in Cuba, Vietnam, Spain, South Africa, Nicaragua or Ireland. A long dormancy of compliance stirs into resistance. There is a feeling of awakening, of self-discovery. The ordinary is elevated to the mythic. Confidence and, in turn, expression grow. If you watched it on television you would think that West Belfast was a place of glass-strewn wastelands, lurking shadows, women on Valium, catatonic children, masked men, medieval fanaticisms, rubble, craters and coffins. If you went there you would find improvised theatres with people sitting on one another’s laps, Irish-speaking children, murals of the Sioux, Bob Marley and Cúchulainn, debates, festivals, transformative housing initiatives. The Armalite eventually left, leaving ballot box, rights campaigns, paint and pen. Thousands participated, among them Gerry Adams.

You have here a book of stories written by someone better known for things other than writing stories. Not all approve of his choices. He tends to be popular with the populace but to draw the ire of the powerful and the influential, in Britain but most particularly in Ireland. Great effort is put into delegitimising him, to denying him rights to be heard that they themselves enjoy, to placing him in permanent quarantine. When in 1993 President Mary Robinson made it known she intended to visit a community event in West Belfast and while there to shake Gerry Adams’s hand, news organisations 14condemned, John Major called Albert Reynolds in alarm, the British ambassador made an official complaint, security protection was withheld and Dick Spring, leader of the Labour Party, spent days imploring her not to do it. She came, she talked, she listened to the McPeakes play reels and shook Gerry Adams’s hand. Afterwards her approval rating stood at seventy-seven per cent. That same year, RTÉ went all the way to the Dublin High Court to defend its refusal to carry a twenty-second ad for this book’s antecedent, a collection of stories called The Street.

But neither the stories of The Street nor these are anthems. They do not intend to convince. There is no party line. In one of those formulations critics make to categorise fiction, it is said that there are two kinds of storyteller – the one who leaves the village, sees the world and returns to describe what he or she has experienced; the other stays home, observes and then describes to the villagers how their life looks. The stories here are definitely of the parish. They venture out briefly to the rural north and to Galway and Dublin, but are otherwise planted in West Belfast, below the Black Mountain. Many from there will recognise themselves, or will think they do. The stories are ironic or funny or poignant or telling, but the most extended and substantial among them are gestures of compassion towards the wounded and marginal, told by someone with a good ear, a responsive heart and access to the kinds of stories often heard only by priests, doctors 15 or, in this case, a community activist and one-time MP. They are sketches or wrought in detail with a fine brush, according to subject and the availability of time. They bear witness, they seek to understand and to advocate for understanding, whether the subject is child, elderly nun, sniper, thief, migrant or a pair of old boys from the Murph looking to scam and with habits as fixed as railroad tracks. The understanding is often surprising, particular and revealing.

In May 2020 I learned he was up against a deadline to finally deliver the collection of stories he’d long been promising The O’Brien Press. I asked him if he’d like me to go over them with him. He took me up on it. It was pandemic time and we went back and forth by email and phone over the summer, usually in the evenings after he’d been all day in meetings about uniting the island, before or after his dinner, before or after he had to write a position paper or funeral oration, sometimes when he was in his garden shed, rainwater dripping from the roof, blackbirds singing, a grandchild calling out, and once during a break he took in Donegal, the sun going down splendidly, he said, over the Bloody Foreland and with Van Morrison’s Veedon Fleece and a glass of wine for company – snatched time in an activist’s life, just as it was during the writing of these stories.

Timothy O’Grady

Introduction

I like short stories. Ever since my Granny Adams brought me to the Falls Road Library when I was a school boy in the 1950s. Until then the Beano, the Topper and the Dandy were my reading material. But the Falls Library introduced me to books. Granted it was Enid Blyton and Richmal Crompton. They soon gave way to Biggles and Tarzan of the Apes and then Zane Grey. Hardly any connection with my life in Belfast. Frank O’Connor and Liam O’Flaherty and Seán Ó Faoláin, Edna O’Brien and Michael McLaverty followed in their own time, along with Charles Dickens, Brendan Behan, John Steinbeck, Ernest Hemingway and Walter Macken. Seamus Heaney was special. And Patrick Kavanagh. Then eventually Gabriel García Márquez, Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, and many, many more who wrote about my kind of people. The working poor. The rebels. The stoic long-suffering mothers. The young lovers. And old lovers too. The heroes and heroines of everyday life. I never imagined then that I would become a published fiction writer. This is my second volume of short stories. The Street and Other Stories was published in 1992. 18

Writing short stories suits my lifestyle. I am usually very busy. It is hard to fit fiction-writing time into an activist schedule. But when I can do it I find the writing experience very rewarding. Apart from my family, I spend a lot of my time in the company of comrades. I have always seen my activism in part as a team effort. I am a team player. I like to think I am a team builder. So I work a lot with others. I believe in the collective. And while I enjoy the company of my friends and comrades, it is refreshing to be on my own and to live in my own head and create the characters who inhabit these pages. Writing is a solitary process. I like that.

I have long admired those folks who can write music and songs or carry tunes in their heads. Musicians are magical people. Painters and photographers also have their place in the arts. Filmmakers. Sculptors. Singers. Poets. Dancers. Actors, too. But writers who can create plays or novels or poetry are special because words are special. We are lucky in Ireland that we have one of the world’s oldest written languages – the Irish language. We also have a lively, living oral tradition in both Irish and English. And while the English language in Ireland is more dominant for obvious reasons, it is a form of English drawn from and influenced by the Irish language. They tried to destroy our language. We Hibernicised theirs. I hope these stories are part of that tradition. Some tell a story which may not often be told. Or heard. If readers recognise themselves or others in these pages, that will please me 19greatly. The essence of storytelling is to uplift, inform, distract and move the reader. To tell their story. Everyone deserves to tell or have their story told.

Storytelling can take many forms. Féile an Phobail (@FeileBelfast) in West Belfast is a wonderful example of this. Born at the height of the conflict, after some dreadful incidents, Féile was a communal response to the awful and untruthful propaganda being peddled by the establishment about the people who live in the west of Belfast city. Some of the stories in this collection are set there. Féile was, and is, a celebration of creativity, resilience, good humour, civic ambition, inclusivity, fun and hope. It is now the largest community arts festival in these islands. That tells its own story.

Writing in Ireland is more democratic now than it used to be. Censorship once was rife. Most of our celebrated writers were banned, from Edna O’Brien to Joyce and many others. And if books weren’t suppressed ‘legally’ by the new Irish state after partition, the Church, before and after partition, pressured the faithful not to read certain books. Books were burned by zealots, their authors denounced from the pulpit. Nowadays no one would countenance such behaviour; although my publisher, the late Steve MacDonogh, was prevented from advertising The Street and Other Stories and other books of mine on RTÉ, the state public service broadcaster. That decision was upheld by the High Court in July 1993.

Irish women writers have carved out their own space in 20Irish book publishing in the recent past. So too have tales of the urban working class, not least because of the writings of Roddy Doyle. Authentic stories from the North about the conflict are not so prevalent, especially from former political prisoners or activists, although my friends Bobby Sands, Danny Morrison, Síle Darragh and Gerry Kelly, Jim McVeigh, Daniel Jack, Maírtín Ó Muilleoir, Tony Doherty, Jake Jackson, Barry McElduff, Laurence McKeown, Pat Magee, Jaz McCann, Ella O’Dwyer, Brian Campbell and others have established themselves as authentic storytellers in Irish and English, and Tom Hartley has distinguished himself as a credible historian, particularly of Belfast’s chequered past.

The act of writing intrigues me. These stories are works of the imagination. Some may be drawn from my own life experience or are influenced by it. But where they actually come from, how they take shape, who the characters are, how the ending emerges is a mystery to me because sometimes that happens by itself. The stories and the people in them seem to take on a life of their own. Do I write for myself? To a certain extent. But not entirely. I would probably write even if my work was never published. But truth to tell, and on reflection, I write mostly for the reader. That’s part of the magic of it, if it’s done properly. The words which are born in the mind of the writer are transferred to the page and come alive in the mind of the reader. Hopefully. From one imagination to another. That’s the whole point of it. 21

And if you can make them laugh or cry? Make them believe? That’s special. Make the reader happy and take them out of themselves. Empower them. Give them hope. Get them to imagine. To remember. And maybe to go on and write or tell their own stories.

Perhaps this is all too pretentious an aim for this modest little selection of stories. If so ignore it. The stories will stand or fall on their own. They are yours. If you don’t like them, give them to someone who might.

Gerry Adams August 2021

Black Mountain

Belfast has hills. Apart from its people – well, most of its people – the hills are what make this city a special place. They are not high hills. They are modest in their inclines. Hardly mountains, although we claim them as such. The Black Mountain or Sliabh Dubh. The Divis and Colin Mountains or An Colann and An Dubhais. Wolf Hill and Cave Hill or Beann Mhadagáin. There are other hills across the metropolis. The Craigauntlet and Castlereagh hills. These slopes hug Belfast in one long, soft, green embrace. They are the backdrop to the city and the main natural feature, particularly of the west of Belfast.

Tom and Harry are two of Belfast’s people. I have known them since our schooldays. They were always close and that closeness has endured beyond their youth, through their working lives, their marriages and beyond, into the autumn of their existences. They survived the conflict, the house raids, riots and decades of military occupation. They were both arrested a few times, but that was a rite of passage for young men growing up in those days. They came through it all. But what makes Tom and Harry unique is not just their 24relationship with each other but their connection with the Black Mountain, which is central to their lives. They walk there every week. Sometimes every day, if the weather permits. For as long as I have known them, it is an important part of how they spend their time. When they were younger they ran there. Back in the day. Loping up the Black Mountain’s green slopes and clambering up its rocky inclines. Sometimes barefoot or in the plastic sandals which were all the rage when we were children. Unlike me, they have persisted with these perambulations. Except for the time when it was too dangerous to venture there, day in and day out these two old pals wander up on to the heights above their neighbourhood.

Nowadays their journey is more of a dander than a walk. A dander is a very leisurely, sometimes hands-in-the-pockets saunter. It should not be confused with a ramble. A ramble could take forever. It may also involve stops at public houses and could include other ramblers who may join in for part or all of the ramble. I have done that myself. Sometimes it was planned. Other times it was an accident. Always it was very enjoyable. A dander is usually fairly short. Tom and Harry rambled the odd time, when they were young, but now they prefer a wee dander. And they rest frequently. And always, if they get that far, they sit in the Hatchet Field and ruminate on matters of importance to themselves. The Hatchet Field, so-called because of its hatchet shape, is a fine vantage 25point up towards the horizon high on the mountainy slope. Nowadays, by the time they reach it they need a good rest. Sprawled on a heathy bank amid the bracken, they are masters of all they survey. Here amid the uncertainties of life is certainty. Like their friendship, it has endured. And they are comfortable about that. Sometimes.

‘The good weather puts everybody in good form,’ Harry remarked. ‘Isn’t it grand?’

He and Tom were sitting in their usual spot. Black Mountain was their eyrie. Belfast sprawled below them. Its narrow-terraced, peace-wall-bisected streets, new apartment blocks, church spires and old mills stretched out until, yellow cranes dominating, their city dipped its feet into the untroubled grey waters of Belfast Lough. In the distance the coast of Scotland shimmered in the clear warmth of a fine day. To the south they could see the Mountains of Mourne and the hills of South Armagh. North-east of that the glimmer of Strangford Lough winked at them.

‘Thon’s our house,’ Tom said as he has said many, many times, pointing down at the Murph.

Harry ignored him. The mountain slope was loud with birdsong. All around them a carpet of bluebells almost on their last legs gave way to verdant green young bracken.

‘Remember when we were wee lads we used to pick primroses up here and bring them home,’ Tom continued. 26

‘I do surely. My ma used to put them in a milk bottle on the scullery window,’ Harry replied.

‘You mean the kitchen,’ Tom corrected him.

‘No, I mean the scullery,’ Harry said. ‘And there’s a place up behind us where we used to get wild strawberries.’

‘Why do you say scullery instead of kitchen?’ Tom enquired with mock earnestness.

‘I don’t say scullery instead of kitchen,’ Harry responded with great patience. ‘In our house these days we have a kitchen. In those days we had a scullery. I don’t call our kitchen the scullery, do I?’

Tom didn’t answer.

‘Well, do I?’ Harry repeated.

‘Nawh, you don’t,’ Tom eventually conceded.

‘Well, if I don’t call our kitchen the scullery, I’m not going to call our scullery the kitchen. I call it a scullery because it was a scullery!’

‘You don’t need to take the needle,’ Tom retorted. ‘Youse Falls Road ones always cry poverty. I was only reminiscing about the primroses. You knew my ma kept the ones I got her in a vase in the kitchen but you just wanted to get in your wee dig about the milk bottle and the scullery. You’ll be telling me next about the cold water tap and the toilet in the yard.’

‘Well, why shouldn’t I?’ Harry asked in an offended tone. ‘Thems the way things were.’ 27

‘Well, they’re not like that any more.’

‘They are for some people.’

‘But not for us! These are good times for us.’ Tom raised himself up on his elbows. ‘Look,’ he continued, ‘when you were here as a wee lad collecting wild flowers for your mammy did you think you would do all the things and see all the things you’ve seen?’

‘No,’ Harry conceded.

‘We’ve been walking these hills for over fifty years now, on and off?’

‘Yup,’ Harry agreed reluctantly. ‘In good times and bad.’

‘Well, you know you’re not going to get another fifty years.’

‘I don’t know about that,’ Harry said with a wry smile. ‘I have a death wish. I wish to die in my hundred and fortieth year.’

‘Your bum’s a plum,’ Tom scoffed. ‘You sound like a buck eejit and you know it. The point is you’re lucky to be able to sit here on this fine day and look down on all this.’ He waved expansively at the vista which surrounded them. ‘The point is to appreciate it all. There’s no use whinging and whining all the time.’

‘Look,’ Harry turned to him, ‘I’m the one that always appreciates it all. You think I came up the Lagan in a bubble? You’re the caster upper, the contrary one, the gurner, the whinger, the dark cloud. And now you’re starting to get 28on my wick. You get on your soap-box just because I used the word scullery’ – Tom raised his hands in frustration and glared at Harry – ‘and because my ma put bluebells in a milk bottle,’ Harry continued. ‘I was gonna go on and say that it’s because of my memories of things like that that I appreciate how things have improved.’

‘Okay.’ Tom smirked. ‘Were you or were you not gonna go on to recall the hard times you had? Were you gonna go on and tell me about getting up early to go for pillowcases of bread down in Kennedy’s Bakery in Beechmount? Were you or were you not gonna go on to recall the big snow of 1963 and how you cut out bits of oilcloth to use as insoles in your shoes because they had holes in them? Were you or were you not gonna retell how youse had coats on your beds instead of quilts in your house? And,’ he concluded, ‘were you or were you not gonna tell how big boys from Westrock stole your snake belt? Or after internment morning, about the way the Paras put you in the back of one of their jeeps and used you as cover when they drove around the district?’

‘I was not,’ Harry protested. ‘That’s something you and the Brits had in common. They don’t understand ordinary people. They think everybody thinks the way they think. As if we have no minds of our own. Just like you. With you it’s your way or no way.’

Despite his resentment at being compared to the Brits, Tom kept his cool. ‘That’s how you know you’ve lost the 29argument,’ he replied evenly. ‘You and I both know that the Brits could never win because you just can’t come into someone’s home place, with all that means, and order them about and expect them to comply.’

‘I’m not asking you to comply,’ Harry countered. ‘Just stop being so contrary. I’m allowed to remember times past without you accusing me of being miserable about it. I’m not miserable about it.’

‘Well, chance would be a fine thing,’ said Tom with a sigh. ‘The point is that was then. This is now. So live in the nowness. Listen to the birds. Breathe the pure mountainy air. Stop gurning. Live in the moment. And appreciate it. You were all set to launch into the five sorrowful mysteries. All set to ruin this lovely day.’

Harry turned away in frustration. ‘Would you ever give my head peace?’ he raged, raising his voice in frustration. ‘How could anyone enjoy the day with you givin’ off about everything. You’re a real gabshite today. You’re like an oul doll.’

‘That’s sexist,’ Tom shot back.

‘Let’s go home,’ Harry said.

‘Aye,’ Tom replied. ‘You’re a pain in the arse today. Can’t even have a discussion without you taking the needle. You’re like a big long drink of misery. It’s well seen you’re kitchen-house reared.’

‘No, I’m not! And you know it.’

They tramped off together, descending the Black Mountain 30slowly and arguing furiously, just as they did when they were only ten years old. Meanwhile, the birdsong continued unabated. The flora and the fauna ignored them. The mountain was a silent witness to their bickering.

And Belfast, basking below, paid no heed.

Eventually, at the top of the Mountain Loney, the steep road down to Ballymurphy, they stopped to draw breath.

Tom broke first. He was feeling a wee bit contrite. ‘I didn’t mean to annoy you so much up there. Let’s not fall out. Isn’t it wonderful weather?’ he volunteered hesitantly.

‘Go hiontach,’ Harry conceded reluctantly. ‘Wonderful.’

Tom has a habit of stating the obvious. But he was right. The weather was gorgeous. A big blue sky stretched over them. The sun beaming down. The Black Mountain was verdant, its greenness highlighted by the sunshine.

They made their way slowly homewards, crossing the Springfield Road at the Top of the Rock.

‘I would love a beer,’ Harry proclaimed. ‘An ice-cold lager. From Belgium or Germany or the Nordic countries. A natural ice-cold lager. Without chemicals.’

Tom looked closely at him. Harry was usually a Guinness man.

‘In a big glass. With the condensation on the outside and a good white head on top. Ahhh,’ Harry sighed, gulping with the effort as he imagined the drink coursing down his throat.

They were nearly home. 31

‘I have some lager in the shed since Christmas,’ Tom confessed.

‘Ah,’ Harry said, ‘I thought I saw it when I borrowed your spade.’

‘When did you borrow my spade?’ asked Tom.

‘Last week,’ Harry replied.

‘What for?’

‘To dig holes for the fence poles for my chicken run.’

‘Ah … When are you getting chickens?’

‘I’m working on it. I have to pick my moment very carefully. Otherwise I’m snookered. I can’t ask until I know I’ll get a yes.’

‘So did you touch the beer?’

‘I did not. I touched nothing but the spade. I wouldn’t mind getting ducks as well,’ he reflected as they cut down to Divismore. ‘Only, ducks like water, and I don’t think I would get away with digging a pool out the back. Getting the chicken run done will be a big enough challenge to my relationship with her who must be obeyed. I’m waiting for the minute when she says she would love a free-range egg. Then I’ll pounce. It’s a matter of patience,’ he concluded thoughtfully, ‘and timing.’

‘My granny used to keep chickens in the coalhole,’ Tom recalled. ‘But not ducks. I like duck eggs.’

‘How many beers have you?’ Harry asked. ‘And how did they survive so long?’ 32

Tom ignored his question. ‘I ate an ostrich egg once,’ he continued. ‘I’ve a cousin working at the azoo. He gave it me. Very strong. Like a big duck egg. I used a pint glass as an egg cup. And a soup spoon to eat it.’

‘I’d have fresh chicken eggs every day if I got chickens,’ said Harry. ‘I might even give you some.’

‘Fear maith thú. That deserves a beer. Here we are now.’

Tom pulled up two chairs at the back of the house. His intention was to drag it out and make Harry squirm before offering him a drink, but by now he had a drought on him, so he went into his shed and came back out with the golden, bubbling lagers. From where they sat, Black Mountain was in plain view. They rested contentedly looking up at its green slopes.

‘You know,’ said Harry, ‘the way an oul’ dog gets up after lying down for a while? You know how it gets up and stretches and gives itself a wee shake. Then it might give itself another wee shake. And another wee stretch. Its coat seems to give a wee shiver. It might yawn as well. Then it slowly danders off?’

‘Aye,’ said Tom, slowly wiping the condensation off his glass while listening intently to Harry.

‘Well,’ Harry continued, ‘I think the Black Mountain is like an oul’ dog sprawled out deep in slumber. I often wonder what we would do if it got up and stretched itself and then dandered off.’ 33

Tom said nothing for a long minute as he looked up at the mountain. And then at Harry. The Black Mountain was omnipresent in the lives of the people who lived below it. Some hardy souls still live at the top of the Loney, and it wasn’t so long ago that a family farmed in the Hatchet Field. Beyond its dark ridge there are old medieval remains, ring forts, ancient quarries where flint arrow and spear heads are still to be unearthed. There are archaeological ruins, old lazy beds. Remnants of human existence since time began. Fairy rings, too, for those who believe in fairies. There are hares and rabbits and pine martens, all types of birds. Bogland and moorland. Mountain meadows and steep rock faces. Mountain streams. Heather and every variety of wild flowers. Tom and Harry were exceptional. They knew every inch of the dark mountainy slopes, its ridges and gullies, its sheep tracks and high passes. Most days, except for the years of military occupation, they looked down from the mountain, never tiring of the vista below them.

In the poorly appointed housing estates at the foot of the mountain, people lived their lives looking up at it. Some, like the working poor in places like this over the centuries, lived tough lives, weighted down by poverty and disadvantage. Perhaps some of them did not look up too often. But the community in the face of adversity became close, mindful of those who lived lives of grinding misery. Local leaders organised and agitated, hopeful that change would 34come. Then conflict erupted and the Black Mountain’s slopes echoed to the sound of gun-shots and explosions, and the stench of CR and CS gas and smoke contaminated the mountain air. British troops dug in and built fortifications overlooking the neighbourhood. They surveyed everything. Every house. Every man and woman. Children even. Every day and most nights they sallied forth to suppress the local populace, including Tom and Harry and their neighbours.

The conflict, now thankfully over, left some of their friends scarred. Others did not survive. Divisions remain. The Black Mountain was impervious to it all. From Neolithic to modern times, from when the first boulder was laid in the wall of a ring fort until the last brick was laid in the new Springhill estate, the Black Mountain witnessed everything. Throughout all those centuries, Tom reflected, it was unlikely that anyone had ever compared the Black Mountain to a sleeping dog. Only Harry could think of that, he concluded.

‘I used to think our walks on the mountain kept us sane. Now, listening to you, I’m not so sure. You know there’s wiser locked up.’ Finally, he sighed patiently, raised his drink and saluted his friend. ‘Sláinte, Harry. I’m sure if the Black Mountain could talk it would have some mighty tales to tell, but let me tell you something – that mountain is not going anywhere.’

‘I know that,’ said Harry. ‘But that doesn’t mean I can’t 35imagine things. It’s like my chickens. Between the two of us, I know I might never get to have chickens. But that’s not the point. I can imagine having them. And the colours their feathers might be, and if I had a rooster would he annoy us all crowing at dawn, and would someone complain, and would the peelers come out to mess me and the chickens about? Would I let some of the eggs hatch out so that we would have wee chicks, wee younkers? That’s what keeps me going. Imagining things. Wee things like a chicken run or big things like the mountain leaving us. That’s what keeps us alive. Imagining. You mark my words. If we lose our imagination we lose everything. Existing is not living. Sure, our Black Mountain walks kept us sane. But our imaginations kept us alive. Through all the troubles. In all the hard times. That’s why we could never be beaten. They couldn’t stop us imagining life without them. You know that. You knew a better life was possible. Or you imagined it. And they couldn’t stop you. If they had done that, we’d be beaten dockets. But we’re not.’ He also raised his drink. ‘Sláinte,’ he said, a little abashed now after his little speech. ‘Up the Murph.’ He downed half his glass in one long gulp. ‘Go raibh maith agat.’ He smiled, lifting the glass again towards Tom.

‘Fáilte,’ Tom replied with a wicked grin. ‘Big Mick gave them to me for you just before Christmas.’

Harry looked at Tom in disbelief. ‘Did Big Mick give you anything else for me?’ he snarled. 36

‘Nawh,’ Tom said. ‘Just the pils. It’s lucky I forgot about them or we wouldn’t be able to have them today.’

‘Aye,’ Harry relented after a minute’s quiet reflection. ‘That’s true. Let’s crack open another couple.’

‘A bird never flew on one wing,’ said Tom.

They sat quietly for an hour or so looking up at the mountain, minding it, as Harry put it, and enjoying the sun. And the beer. Two old pals. No one to interrupt them. Their squabble was forgotten as they listened to the children playing in the street and a neighbour cutting his hedge. The cheerful jingling tune from an ice-cream van meandering its way along Springhill Avenue added to the lazy sunny mood. Soon dinner-time drew near and Harry made ready to go.

‘Good luck with the chickens,’ Tom said to him.

‘I’ll need luck with herself first,’ said Harry.

‘There’s that right enough,’ said Tom. ‘Do you think you’ll be able to go up the mountain for another dander tomorrow?’

‘Aye,’ Harry said. ‘No problem. Give me a shout when you need me. By the way, does that cousin of yours who gave you the ostrich egg still work in the azoo?’

‘Nawh,’ Tom said. ‘But Big Mick knows a man who knows a man who has alligator eggs.’

Harry shook his head. ‘Nawh,’ he said. ‘I’ll stick to Rhode Island Reds, if you don’t mind. Thanks again for the beer. Even if it was me own. It rounded off a fine day.’ 37

‘Aye,’ Tom agreed. ‘Now we’ve finished yours I’m going to get stuck into mine.’

Harry stopped in his tracks. ‘You cannot be serious.’

‘I’m only jokin’.’ Tom laughed.

Harry looked doubtful. ‘I don’t know whether to believe you or not!’ he exclaimed.

Tom eased him through the door. ‘I’m only keeping you going. See ya,’ he said. ‘Tomorrow about twelve,’ he shouted at Harry’s departing figure.

‘Slán,’ called Harry.

A fine day indeed, Harry thought to himself as he meandered homewards, where he had planked a few other bottles of beer that Big Mick’s mate Wee Mick had left for Tom and himself. Big Mick and Wee Mick ran the local off-licence for a local businessman, Peter O’Property. Peter’s real name was O’Toole but everybody called him O’Property behind his back on account of the real estate he had gathered up since the ceasefires. Big Mick and Wee Mick were discreetly generous with his wares to selected off-licence customers.

So after his short walk home, Harry poured himself a scoop. He too seated himself outside, the Black Mountain still the vista that towered above him. Meanwhile, Tom made his way back to the shed where he gathered up another bottle of the secreted lager. One of the ones Harry didn’t get. He returned to his seat facing the mountain and poured himself another glass. Then, with a satisfied little sigh, he raised it in salute to 38his absent pal. ‘Sláinte, Harry, old friend.’

And there, dear reader, we will leave them. In the shadow of Black Mountain, where they have lived all their days. Each drinking the other’s beer and enjoying it all the more because of that.

Tomorrow on Black Mountain is another day to look forward to. Especially if you’re lucky and have the ability to imagine things.

First Confession

One night a week we used to go for our religious instruction to confraternity down in Clonard Monastery, and if we left early we could spend the bus fare on sweets. We cut down the Springfield Road and joined hundreds of other boys in the chapel. To me Clonard was a wondrous place with high, high ceilings and a huge high altar. The altar boys wore long red soutanes and white gowns. The priest’s incense spiralled upwards through the shafts of sunlight which came slanting down from stained-glass windows at the very top.

It wasn’t a long service. Father McLaughlin, who was in charge of the confraternity, got up and made a joke or preached a sermon and then we sang a few hymns. I didn’t mind it at all; in fact, I found parts of it good fun. As Father McLaughlin conducted the whole chapel full of young fellows, we would sing ‘Tanto Mergo, make my hair grow’. Every section of boys had a prefect, and we had to be careful in case we’d be caught.

It was evening by the time we came out of ‘confo’, and the evening had a different feel, with shadows coming, the 40day having cooled off; we could sense the change, and things became quieter as we embarked on a rambling return home through territory we regarded as our own long-extended playground

We walked up the road, often stopping at the Flush River. Here beside the cotton mill there was a deep ravine, and often we slid down its high slopes right down to the river. Although we weren’t allowed in the river, we were forever going into it. However, one of us was found out once when, having dried himself off, he went up home.

‘You were in the river,’ his mother said as soon as she saw him.

‘No,’ he lied, ‘I wasn’t.’

‘You were,’ his mother said, pointing to his head and the back of his clothes, which were decorated with white patches. There had been bleach in the river that day and he was rightly caught.

Once some wee lads stoned us at the Flush and we ran like anything; somebody said they were Protestants, but I didn’t know what they were stoning us for. Up above the Flush a school stood off the road behind a tall wall, and opposite it were two terraces of houses, a small street and a shop; the people there were all Protestants except for one fella we used to call to sometimes if his father wasn’t in.

Carrying on towards home, it was all green fields, and as we passed the Springfield dam we stopped to watch the 41swans, the water herons and, at different times of year, the ducks.

Opposite the Monarch Laundry on the right-hand side lay the Highfield estate and the West Circular Road where mostly Protestants lived; above stood an Orange hall. Away on up lay more fields: Huskey’s on the left-hand side of the road, Farmer Brown’s and Beechie’s on the right. On yellow houses here a date indicated that they had been built a hundred years or so before.

Then we arrived on home ground: the Murph. Down the slope, the steps, Divismore Park and our house. And if we were slow coming up, having played at the Flush too long, when we reached as far as Divismore Park we might hear the long shouts of our Margaret: ‘Geeeerrrryyy, you’re a-wanted!’ and ‘Paaaaddddyyy, you’re a-wanted!’ The sounds might be heard too of others out shouting for Joe or Harry or Frank. Then the lamps were lit as Divis Mountain began to fade and the stars appeared.

Sometimes we would stand, put our heads straight back and look up at all the thousands and millions of stars. One night Joe Magee’s dad brought us just about half a mile above the Murph to listen to the corncrakes. That was beautiful, and from a height we had a view down over the city of Belfast; then we put our heads back and looked up at the sky, all the time hearing the corncrakes.

The priest told our class that we had to tell all our sins 42in confession. I wondered about that. How could you tell all your sins? Every single one? I started to try to take notes when I was committing a sin, which was fair enough because I had a week to go till my first confession, but all the sins, of my whole life? Sean Murphy, who sat in the desk beside me, said it was only mortal sins; venial sins didn’t really matter. Sean said that Protestants got it easier: they didn’t have to go to confession; they didn’t have to tell their sins. But then, Protestants weren’t going to get to heaven, he said.