8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

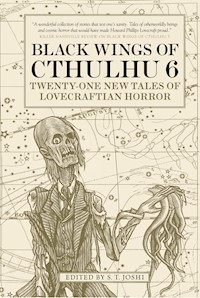

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Volume 6 in the successful and critically acclaimed series of Lovecraftian horror anthologies by the most prominent acolytes of the horror master.From claustrophobic fear in isolated New England towns to terrifying threats that span the infinite cosmos, the tales herein are fuelled by H. P. Lovecraft's creations. While his horrors originate in a vast cosmos outside of space and time, the terrors they bring strike ordinary humans caught up in conflicts far beyond their control. This volume offers a who's who of Lovecraftian authors including Aaron Bittner, Adam Bolivar, Jason V Brock, Ashley Dioses, David Hambling, Lynne Jamneck, Mark Howard Jones, Caitlín R. Kiernan, Nancy Kilpatrick, Tom Lynch, D. L. Myers, William F. Nolan, K. A. Opperman, W. H. Pugmire, Ann K. Schwader, Darrell Schweitzer, Steve Rasnic Tem, Jonathan Thomas, Donald Tyson, Don Webb, and Stephen Woodworth. Gathered together by S. T. Joshi, their works are certain to thrill.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

S. T. Joshi

Pothunters

Ann K. Schwader

The Girl in the Attic

Darrell Schweitzer

The Once and Future Waite

Jonathan Thomas

Oude Goden

Lynne Jamneck

Carnivorous

William F. Nolan

On a Dreamland’s Moon

Ashley Dioses

Teshtigo Creek

Aaron Bittner

Ex Libris

Caitlín R. Kiernan

You Shadows That in Darkness Dwell

Mark Howard Jones

The Ballad of Asenath Waite

Adam Bolivar

The Visitor

Nancy Kilpatrick

The Gaunt

Tom Lynch

Missing at the Morgue

Donald Tyson

The Shard

Don Webb

The Mystery of the Cursed Cottage

David Hambling

To Court the Night

K. A. Opperman

To Move Beneath Autumnal Oaks

W. H. Pugmire

Mister Ainsley

Steve Rasnic Tem

Satiety

Jason V Brock

Provenance Unknown

Stephen Woodworth

The Well

D. L. Myers

About the Editor

Also Available from Titan Books

BLACK WINGS OF CTHULHU 6

EDITED BY S. T. JOSHI

AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Black Wings of Cthulhu

Black Wings of Cthulhu 2

Black Wings of Cthulhu 3

Black Wings of Cthulhu 4

Black Wings of Cthulhu 5

Black Wings of Cthulhu 6

The Madness of Cthulhu

The Madness of Cthulhu 2

BLACK WINGSOF CTHULHU 6

TWENTY-ONE NEW TALES OFLOVECRAFTIAN HORROR

EDITED BY S. T. JOSHI

TITAN BOOKS

Black Wings of Cthulhu 6

Print edition ISBN: 9781785656934

Electronic edition ISBN: 9781785656941

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St, London SE1 0UP

First Titan edition: October 2018

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Previously published in November 2017 by PS Publishing Ltd. by arrangement with the authors. All rights reserved by the authors. The rights of each contributor to be identified as Author of their Work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Copyright © 2017, 2018 by the individual contributors.

Introduction Copyright © 2017, 2018 by S. T. Joshi

Cover Art Copyright © 2018 by Gregory Nemec

Caitlín R. Kiernan, “Ex Libris,” first published in The Yellow Book by Caitlín R. Kiernan (Subterranean Press, 2012), copyright © 2012 by Caitlín R. Kiernan With thanks to PS Publishing

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers.

Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at

Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website

WWW.TITANBOOKS.COM

“The one test of the really weird is simply this—whether or not there be excited in the reader a profound sense of dread, and of contact with unknown spheres and powers; a subtle attitude of awed listening, as if for the beating of black wings or the scratching of outside shapes and entities on the known universe’s utmost rim.”

H. P. LOVECRAFT,

“SUPERNATURAL HORROR IN LITERATURE”

Introduction

THE INFINITE MALLEABILITY OF LOVECRAFTIAN motifs, as exemplified by the contents of this volume, calls for some discussion. Why has H. P. Lovecraft’s work been such an inspiration to writers of weird fiction over the past century or so when other meritorious writers—ranging from the “modern masters” identified by Lovecraft himself, Arthur Machen, Lord Dunsany, Algernon Blackwood, and M. R. James, to such recent luminaries as Stephen King and Ramsey Campbell—failed to do so?

The history of Lovecraftian pastiche would make an interesting study in itself, and I have attempted to do so in my treatise The Rise, Fall, and Rise of the Cthulhu Mythos (2015). That book shows that, once writers put aside the mechanical imitations—which in many cases extended merely to the invention of a new “god” or new “forbidden book,” even if the overall theme of the story was anything but Lovecraftian— practised by such writers as August Derleth and Brian Lumley, a new era emerged. Writers now began searching more deeply into what exactly went into the making of a “Lovecraftian” story—and came to the conclusion that a multiplicity of motifs could be drawn upon, in contexts Lovecraft himself would scarcely have recognised, with the result that writers could infuse their own personalities into a work that nonetheless draws upon themes pioneered by the dreamer from Providence.

The central message of Lovecraft’s work, to be sure, is cosmicism—the depiction of the infinite gulfs of space and time and the concomitant insignificance of the human race, and all earth life, in the overarching history of the cosmos. In his earlier stories, Lovecraft used the figure of the “god” Nyarlathotep as a symbol for this cosmic menace. Archaeological horror was also a powerful means by which Lovecraft conveyed the essence of cosmicism, and Ann K. Schwader (“Pothunters”), Lynne Jamneck (“Oude Goden”), Don Webb (“The Shard”), and Stephen Woodworth (“Provenance Unknown”) have followed this methodology.

For Lovecraft, the sense of place was supremely important. Here was a man who spent every spare penny in exploring havens of antiquity from Quebec to Key West, from Marblehead, Massachusetts, to Charleston, South Carolina. He enlivened his native New England with an entire constellation of imagined cities where anything can happen; and in this volume, Tom Lynch’s “The Gaunt” takes us to Lovecraft’s Arkham, while Aaron Bittner (“Teshtigo Creek”) duplicates Lovecraft’s regional horror in North Carolina, and veteran W. H. Pugmire (“To Move Beneath Autumnal Oaks”) etches new lines of terror in his carefully crafted Sesqua Valley in the Pacific Northwest. Darrell Schweitzer does much the same thing in the rural Pennsylvania setting of “The Girl in the Attic.”

Alien creatures—whether it be the fish-frog entities from “The Shadow over Innsmouth” or the inbred gorilla-like monstrosities of “The Lurking Fear”—are ever-present in Lovecraft, signalling his fascination with the anomalies of hybridism and the potentially loathsome mutations of the human form. It is this motif that animates such variegated tales as William F. Nolan’s “Carnivorous,” Nancy Kilpatrick’s “The Visitor,” and Steve Rasnic Tem’s “Mister Ainsley.” Jonathan Thomas’s “The Once and Future Waite,” an ingenious riff on “The Thing on the Doorstep,” suggests unthinkable transferences of soul and body, while Jason V Brock’s “Satiety” not only plays a clever riff on the half-plant, half-animal entities in At the Mountains of Madness but makes pungently satirical references to recent controversies about Lovecraft’s status in contemporary literature.

Caitlín R. Kiernan takes Lovecraft’s “forbidden book” theme and turns it into a means for probing the psychology of fear in “Ex Libris.” In their various ways, Mark Howard Jones’s “You Shadows That in Darkness Dwell” and Donald Tyson’s “Missing at the Morgue” make use of Lovecraft’s recurrent theme of other worlds lying just around the corner from our own. David Hambling’s “The Mystery of the Cursed Cottage” performs the nearly impossible by fusing the locked-room detective story with Lovecraftian elements.

This volume includes not one but four poems in the Lovecraftian idiom—a testament both to the renaissance of weird poetry in our time and to the felicitous adaptability of Lovecraftian motifs in the realm of verse. Ashley Dioses, Adam Bolivar, K. A. Opperman, and D. L. Myers have all distinguished themselves as poets of technical skill and emotive power, and their verses exhibit the quintessence of terror while adhering to the strictest standards of formal rhyme and metre.

There is no reason to believe that Lovecraft’s dominant role in the creation of contemporary weird fiction will end anytime soon, and the future should reveal still more innovative treatments of the themes and imagery he fashioned out of the crucible of his imagination.

S. T. JOSHI

Pothunters

ANN K. SCHWADER

Ann K. Schwader’s most recent fiction collection is Dark Equinox and Other Tales of Lovecraftian Horror (Hippocampus Press, 2015). Her most recent poetry collection is Dark Energies (P’rea Press, 2015). She is a two-time Bram Stoker Award Finalist, a two-time winner of the Rhysling Award, and the Poet Laureate for NecronomiCon Providence in 2015. Schwader lives and writes in Colorado.

1

WHATEVER WAS IN THE PACKAGE, JUPE AND JUNO DIDN’T like it. Instead of begging shamelessly for biscuits from the carton Cassie had just brought back from Sheridan, the Rott siblings were pacing around the kitchen table, whining.

She ignored them until she’d put away the groceries. No matter what was going on, Twenty Mile wasn’t doing nearly well enough for her to waste frozen food. Not with this fall’s two-year-olds still to ship.

It took her a good ten minutes to finish, but the dogs never let up.

As she checked through the week’s mail on the table, a too-familiar chill traced her spine. Aside from that box addressed to C. BARRETT, there were only magazines, bills, and junk mail in the pile. Nothing else they’d be likely to react to. Nothing she’d better figure out before a few years’ worth of bad memories kicked in.

Cassie picked up the shoebox-sized parcel and checked the rest of the address. Then she headed straight out to the front porch, where her foreman was waiting to talk chore lists.

“Frank, why is somebody with your last name sending me stuff from Santa Fe?”

Frank Yellowtail looked up from his coffee and scowled. “Probably because I told him not to.” The scowl deepened. “Joshua’s got a stubborn streak a mile wide. Thought the Army might fix that, but it didn’t.”

Her own jumbo mug o’ sanity suddenly seemed like a great idea. Handing over the package, she went back inside to pour herself one—and quiet Jupe and Juno, now whuffling anxiously through the screen door.

By the time she returned, Frank had the box unwrapped.

“Sorry,” he said, passing it back. “After the emails I’ve been getting from that kid these past couple of weeks, I wasn’t sure what he might have sent.”

He glanced past her at the Rotts. “And when those two started in—”

He didn’t need to finish. The early September twilight suddenly felt colder—in a way that had nothing to do with thermometers.

But everything to do with what Frank’s grandfather, a Crow “man of power,” had called frostbite: that sensation you got when the Outside touched your smug little reality, and you knew right away because you’d been there before. Or almost there, because folks who went all the way there didn’t come back.

“So who’s Joshua? And what’s he been telling you about this package?”

Frank didn’t answer immediately. Pulling tape from the box’s lid, Cassie lifted it off to reveal wadded newspaper with a couple of envelopes on top. A smaller box nestled inside.

And I’m not digging in until I get some answers.

“He’s my youngest brother’s boy,” Frank finally said. “Went to Afghanistan, went to Iraq, then figured he’d had enough. He’s been working security down in New Mexico for a few years now.”

Cassie kept waiting.

“Last fall, there was some serious rain around Bandelier. Afterwards, the park service found a small side canyon the flood waters had unblocked. There were caves dug into the canyon walls—”

“Cavates?” Cassie leaned forward. “Like an Anasazi site?”

“Maybe.”

Frank’s tone had changed, and she wasn’t sure she wanted to know why. Southwestern archaeology was a long-term fascination, but after Zia House—and a certain “Chacoan outlier”—two years ago, she’d learned to look beyond ancestral mysteries of kivas and cavates and petroglyphs. To recognize them as faint shadows of something other—

“So what’s this new site got to do with your nephew?” she asked at last.

“After the park service roped off that canyon entrance, they got the state university involved right away. Didn’t want the risk of looters—or lawsuits—if human remains turned up. The anthropology department got all excited and sent somebody out.”

Frank took a long pull on his coffee.

“And?”

“The idea was to investigate quietly. Maybe there wasn’t anything to find. Maybe there was, but some local pueblo had to be consulted. Everything went fine over the winter: site approval got hustled through; grants got written. Come spring, the real work started, and then—”

“The media found out?”

“Something like that.” Frank hesitated. “Joshua thinks they were tipped off by someone at the site—at least, that’s what he was told when the university hired him. After the trouble started.”

Cassie frowned. “Pothunters?”

“Right away. Like they knew what they were looking for, or at least where to find it.”

Her frown deepened. Pothunters were archaeological vermin, and the rural Southwest made an ideal habitat. The region’s meth plague only added to the problem: artifacts became a handy source of cash for addicts, so long as they found a buyer who’d ask no questions.

Or, better yet, swap finds for drugs directly.

“Sounds like Joshua’s got himself a steady job for a while.” She looked down at the box in her lap, suddenly suspicious. “Want to tell me the rest?”

Frank picked up his coffee again. “Not really.”

The smaller of the two envelopes in the box held a letter addressed to her—a long one, with handwritten annotations in the margins of the printout. Cassie paged through it quickly. And set it aside even more quickly.

The second envelope was filled with newspaper clippings, photocopies, and a few photographs. Most of the clippings were from the Santa Fe New Mexican. A few came from the Albuquerque Journal. The photographs were digital images run on a home color printer.

All but one showed pots, most of them in situ and vaguely similar. They were large containers—canteen-style rather than flat seed jars—and looked to be a version of black-on-white. On some of the photos, the jars’ mouths had been circled with red felt-tip.

Cassie picked one up to examine closely. Then another, frowning.

Spiderwebs?

She checked through all the photos with circles. There was certainly something sealing the mouths of those jars, but it looked too solid to be the work of any spider she’d ever seen. Or wanted to see.

Setting the photos aside, she dug out the smaller box. It was simple white cardboard, its lid taped down securely.

Jupe and Juno started whining before she even got the tape off.

The potsherd inside looked like a piece from one of the photographed pots: black-on-white, with fresh broken edges. What she could see of the dark clay itself told her nothing, but a grayish sticky tangle marred the sherd’s design.

She wrapped her fingers with a tissue before picking it up. A closer look revealed more of the not-quite-spiderwebbing.

Replacing the potsherd in its cotton, Cassie closed the box and dropped it back into the wadded newspapers. Both dogs quieted down. Gathering up the clippings, photographs, photocopies, and letter pages, she tipped them all back into their envelopes and took a deep breath.

“Anything else you don’t want to mention? Like why your nephew wants me involved?”

The old kitchen chair Frank sat on creaked ominously. “It’s all in the letter.”

Cassie sipped at her cooling coffee and waited, trying not to think about the one photograph that hadn’t been pots. It had been dated on the back (about two months ago) and showed crime tape around a patch of sparse grass and red soil. A sheet mostly covered a long lump inside.

“Joshua’s got a big mouth,” Frank finally said. “And his cousin down there’s got time on her hands lately. She told you about that, right?”

Julie Valdez was Frank’s favorite niece. She was also a dedicated anthropology grad student at the U. of New Mexico. This past spring, her Northern Tewa husband had finally made her choose between Taos Pueblo with him or “wasting her life” on Ph.D. work.

Last Cassie had heard, Julie’s wasted life was going just fine. Unfortunately, an earlier part of it involved that summer field school at Zia House—and some, though not all, of what had happened there. Although Julie’s research skills had proven invaluable since, Frank was never glad to see her get involved.

He wasn’t looking glad now.

“After that . . . incident two months back, the whole dig nearly got shut down. Nothing was ever found at the site, though. After the sheriff’s department lost interest in one more meth statistic, everybody got back to work.” Frank frowned. “But the questions never stopped. And the board of regents started asking their own.”

Cassie couldn’t blame them. Along with the body in that crime tape photo, there had been several large black-on-white potsherds littering the ground.

“Let me guess,” she said. “Julie’s working at this site?”

“No, but her department’s involved. When Joshua called her about his dead pothunter problem, she did a little digging into the area’s history.”

He gestured toward the envelopes in her lap.

“I’m guessing it’s all in that letter, but strange things have happened there before. Just not lately. Julie wanted to go check into it herself, but she’s a teaching assistant now. She suggested that maybe the site director could take on a volunteer—”

Cassie stiffened. After what she’d seen in that “outlier” two years ago, she’d limited her archaeological involvement to working through her magazine piles. Weirdness found her often enough these days without her going looking for it, let alone accepting invitations to look.

Besides, this was a lousy time to be away from Twenty Mile. There were cows and calves to be moved for the winter, two-year-olds headed for market—that chore list she and Frank still had to discuss ran at least two pages. Whatever his nephew thought might be going on around Bandelier could wait.

When she said as much, though, Frank shook his head. “Maybe you’d better check through that letter first.”

The last time he’d sounded this serious about anything but ranch business, it had been January. And she had been snowed in down in Warren, Wyoming—a very small town with a very big weather problem. Which turned out to be neither meteorological nor natural.

Cassie gave the chore list on the porch railing a parting glance. “Guess I’ll go do that,” she said, draining the last of her coffee.

One more test. “And then I’m guessing I’ll have to get McAllister’s box out.”

Frank didn’t even blink.

2

TWO MEATLOAF SANDWICHES AND WAY TOO MUCH caffeine later, Cassie was certain of only one thing: pothunters were the least of Joshua Yellowtail’s troubles.

His letter left no doubt that he suspected this. Fanned out on her desk in all its single-spaced glory, its margins crawled with handwritten notes and rough sketches. Most of the contents came from a log he’d been keeping on his laptop since being hired at the site.

After the first couple of pages, she’d hauled Daniel McAllister’s box from the bottom of her closet.

Her hands shook as she unwrapped the old quilt she used for camouflage, even after telling Frank about the box last winter. Post-Warren. The battered beer carton—labeled C. BARRETT PLEASE OPEN in black marker—was another souvenir of Zia House. And the unasked-for legacy of its caretaker: a former professor of Southwestern archaeology who’d fallen victim to unsanctioned curiosity, alcohol, and the Outside.

She’d first met McAllister while searching for a missing fellow student. Rather than helping her find the guy, he’d shared his own experience with the brand new paradigm Zia House’s recently discovered “outlier” represented. He’d also lent her a monograph that had wrecked her sleep, but probably saved her life.

She’d never gotten the chance to return An Ethnographic Analysis of Certain Events Associated with Earthen Structures in the Vicinity of Binger, Western Oklahoma, in the Year 1928. Instead, she’d added it to the box she’d found while unpacking her Jeep afterwards. Along with a stack of his own field journals, McAllister had included a letter. Heavily annotated with references to the Binger monograph and several other sources, it linked Southwestern sites and myths to others less familiar.

And far, far older.

After rereading that letter a few months ago, she’d shoved it behind the bookcase next to her desk. Retrieving it would be a pain, and she doubted she’d forgotten its contents—however much she’d tried to. McAllister hadn’t said much about pots or Bandelier, anyhow.

Not in those pages. But in his journals?

C. BARRETT PLEASE OPEN. As if I have a choice. Lifting out the worn hardbound notebooks, she began searching through them for significant terms. Bandelier, of course (both the Swiss-born anthropologist and the site), but also Frijoles Canyon, Tyuonyi, Pueblo III Era, Pueblo IV Era, and Jemez Mountains. On a hunch, she included black-on-white.

Even so, she didn’t find much at first. Before his academic— and legal—fall from grace, Daniel McAllister’s specialty had been the Chaco Phenomenon. It was only later, with grants and university support long gone, that he’d turned to more obscure sites.

But when he had—

Cassie’s fingers tightened on the stained page she’d been skimming. In the center, under the notation cavate wall? Frijoles Canyon area? and an illegible date, McAllister had sketched a petroglyph. One unlike any she’d seen at the sites she’d visited, or in the few related books she owned.

And not one she’d have overlooked.

She examined the sketch more closely. It was winged, definitely; but not the stubby wings of a parrot or a macaw glyph. Nor the mere lines of a dragonfly. These were widespread and strong, fully as large as the body. But the body of what?

Neither bird nor insect seemed likely: the outline was blocky and crablike, with crooked lines suggesting multiple pairs of legs. A small knob bristling with shorter lines and one longer, curled line (proboscis?) topped it off. Something mythical, then; or spiritual.

Or worse.

Cassie’s frown deepened. Last holiday season, she’d volunteered at a charity workshop outside Sheridan—and learned more than she wanted to about Authentic Ancient Designs for a Stronger Community.

Maybe McAllister had, too. Underneath the sketch, he’d added some fragmentary notes. Pennacook Winged Ones myth? Vermont floods 1927? The Akeley incident?

None of these referents helped, but a faint chill traced her spine. The next few pages held three more sketches. One was labeled Petroglyph National Monument, recent discovery. The other two came from more obscure sites still close to Bandelier.

Though all the glyphs were similar, they weren’t identical. One showed that longer curled line uncurling—toward a possibly human figure. In two others, the wing positions suggested flight. And in one of these two, the crooked lines bent around (grasped?) something.

She held the notebook closer and squinted. A circle, maybe. Or a cylinder. Or a pot.

Asked around the [illegible] pueblo, McAllister’s notes continued underneath. Not many recognized it. Those who did— all elders—reluctant to explain. Finally tried trading post at [illegible] & got wild tourist story about moon-flyers—

That story took up the next several pages. McAllister’s speculations and commentary occupied a few more. When she finally finished, Cassie left the journal open and returned to Joshua’s letter, wishing she’d made herself a stiff rum and Coke instead of more coffee.

He hadn’t noted any strange petroglyphs at the new site, but there were plenty of pots. Most had been found far in the backs of cavates, nestled in small groups. Almost all had their mouths sealed, though no insects or spiders were entangled in the webbing. No sherds or damaged ceramics had been found— only whole vessels, in remarkably fine condition.

At least until the pothunters found them.

Cassie swore under her breath as she read. Meth addicts were tireless scavengers, but that excess energy made for twitchiness—and sneaking around with flashlights didn’t help. Things were bound to get broken. Since there were plenty of pots, nobody cared all that much.

Nobody but Joshua’s boss, one Dr. Antoñia Alvarez. According to him, she took every sherd like a personal injury; or the remains of some endangered species. Their particular black-on-white design was, so far as she knew, unique to the site. She’d sent out samples and photos to several other scholars, without success.

In a last-ditch search for clues, she’d even given one fragment to a chemist friend at the university. Results hadn’t come back yet, but she felt certain—

Cassie’s breath caught. A unique ceramic design. An extremely localized petroglyph. And both from around the same previously untouched site.

Grabbing McAllister’s journal with its “tourist story,” she laid it next to Joshua Yellowtail’s letter and started comparing. Joshua’s boss hadn’t said anything about moon-flyers, but she had mentioned a local rumor about the summer night walks at Bandelier. A few years back, one of those walks featured a full moon—and some very strange shadows had flitted across its face.

Everyone knew there were bats in Frijoles Canyon, but even the ranger leading that walk hadn’t been able to convince a few observers that they’d seen bats. The result was an article in the Santa Fe New Mexican, which Joshua had helpfully photocopied.

Cassie read it over a couple of times, checked McAllister’s sketches, then brought up a moon-phase app on her phone and entered the date on that not-just-pots photo.

Five minutes later, she was packing.

3

EASING HER JEEP DOWN THE BOULDER-STREWN TRAIL she’d barely found on Joshua’s map, Cassie felt cold sweat down the back of her neck. On this afternoon of flawless skies and piñon-scented breezes, she was driving into trouble. And she knew it.

Despite all the details she’d been rereading these past two days on the road to New Mexico, Frank’s nephew hadn’t told her everything. Not about his past month at the site, anyhow. Those last pasted-in logs hadn’t just been briefer; they’d been vaguer, as though he’d been struggling not to say something.

What he had managed to put in was disturbing enough.

While trying to identify that black-on-white design, Dr. Alvarez had taken her sherds and questions all the way to Gallup, Mecca of trading post junkies. Even the shop owners there couldn’t help—which hadn’t stopped them from passing on local rumors about the Bandelier area.

Some of those rumors were even weirder than McAllister’s. Alvarez hadn’t known to ask about petroglyphs, but moon-flyers (or something similar) still came up. Like the Roswell aliens, there were no well-documented sightings, and a fair number of others involved alcohol. There was little agreement about their appearance. Some said crustaceans, some said bats or insects, and others claimed that they shifted forms or resembled something else entirely.

Almost all sightings had happened around full moons.

Since none of these stories involved ceramics, Alvarez had eventually given up and returned to her site. Later inquiries around Museum Hill in Santa Fe hadn’t yielded much more, aside from one docent at the Wheelwright whose Navajo great-grandmother had advised her to stay out of those canyons.

Meanwhile, despite Joshua Yellowtail’s best efforts, pothunters kept raiding. Night after night, they found new caches. Morning after morning, Alvarez picked up sherds and swore. Joshua suspected someone on her team was feeding information to the looters. Alvarez was sure of it—which was why she’d pushed through Cassie’s paperwork.

And my last volunteer experience went so well.

Cassie death-gripped the wheel as one front tire almost dropped into a hole. Beyond it, the trail widened into a clearing with a few other vehicles. After parking her own, she reached into the glove compartment for her carry pistol, checked it, and holstered it beneath her shirttail.

The process still felt awkward, but there was no sense being stupid. Not after last winter. Finances were always tight at Twenty Mile, but Frank had looked relieved when she’d signed up for permit classes. No more worrying about being pulled over with the big .44 she used to hide as road medicine. No more going into situations unprepared.

Assuming the situation could be prepared for.

As she walked down into the narrow canyon, she was surprised by the number of cavates pocking its walls. None of the articles Joshua had sent mentioned past inhabitants. Aside from ceramics, there had been little of archaeological interest: no trash middens, no tools or weapons. And until two months ago, no human remains.

Meeting the gaze of those blind shadow eyes, she felt her breath catch. If humans hadn’t been digging into the tuff here, what had?

A few minutes later, the flapping of a bright blue tarp told her she’d arrived.

“Cassie?” One of the three people under that tarp—a youngish man in a khaki uniform shirt—raised a hand to shade his eyes. “Cassie Barrett?”

Cassie grabbed the strap of her backpack and trotted the last few yards.

“Sorry I’m late,” she said, mostly to the woman beside him. “I did have a map, but—”

Dr. Antoñia Alvarez waved away her apology. “Maps don’t work too well out here.”

Alvarez was forty-something and fit, though her dark eyes had darker shadows under them. She’d been sitting at a folding table with her laptop and a tray of potsherds, but set them aside as Cassie approached.

“Don’t know why I bother.” She glanced ruefully at the sherds. “I have no idea where most of these came from, and there’ll be more tomorrow.”

Her gaze shifted to a thin blonde girl packing up equipment nearby.

“We’ll take care of that, Kit. You can go on back to town.”

Cassie expected the girl—a grad student?—to head out immediately, but she took her time. Alvarez stayed quiet until she’d disappeared up the trail.

Joshua Yellowtail seemed equally uncomfortable.

“Glad you could make it, Cassie,” he finally said. “After talking to Uncle Frank—”

“He was all right with it. For a few days, anyway.”

Joshua’s expression didn’t change. Both of them knew how little Twenty Mile could spare even one pair of hands right now. When Alvarez motioned toward an empty chair, Cassie sat gratefully.

“Your paperwork came through fine,” Alvarez said. “Julie Valdez said good things about you, and you’ve had enough applicable coursework to keep my department happy.”

She handed her a volunteer form and a pen. “Of course, it’s still a short-term position.”

Cassie nodded. “Like maybe three days?”

Alvarez gave Joshua Yellowtail a hard look. “I thought we discussed—”

Not telling me what the hell is really going on down here?

“I checked the date on that picture with the crime tape,” Cassie finally said. “It was a full moon, two months back. And the pots—or at least the sherds—around here got you some ‘moon-flyer’ rumors in Gallup.”

Her hand fastened on the backpack propped against her chair.

“There have been other rumors like that, in this part of the country.” And petroglyphs to go with them. Which means a long time. “Three days and nights from now is also a full moon—the Harvest Moon.”

Cold certainty shot down her spine.

“So what happened here on the full moon last month?”

For a moment, there was no reply but the distant cicadas.

Then Joshua picked up his phone, opened it to a picture, and passed it over.

It was a night shot, slightly out of focus. The body of a young woman—fully dressed, ratty jeans and a tank top—sprawled on dirt. She’d been pothunting: a nylon knapsack gaped open for her latest find, now shattered on the ground nearby. Even in flash glare, Cassie recognized its distinctive design.

That wasn’t what made her breath catch, though.

“How did she—?”

“No clue.” Joshua’s voice was tight. “But I think I found her right after it happened, whatever it was.”

Both of them glanced down at the phone. At the girl’s face twisted in a frozen shriek, mouth wide open and bloody.

“I was checking one of our latest find spots,” Joshua continued. “Thought I heard somebody back in a cavate. Not close, so I thought I’d come up quiet and nail them when they crawled out.”

He hesitated.

“A couple of minutes later, I heard buzzing up ahead—but not like insects. Not like any insect I’ve ever heard, anyhow. Almost felt like it was going through my skull—or maybe inside it—”

Another silence. Longer.

“—and then there was this one short scream. A girl’s. But it wasn’t cut off. More like choked off, like somebody shoved something down her throat.”

Still staring at the phone screen, Cassie forced herself to nod.

“By the time I got there, she was . . . like that. The buzzing was gone. And there were sherds everywhere—”

He glanced a question at Alvarez.

“Go on,” she said. “Might as well tell it all.”

“After last time, I figured we’d get shut down for good if I called in another death. So I didn’t.” Joshua raked a hand through his short hair. “I put the body in a cavate looters had already emptied. And then I picked up every last piece of that pot.”

Cassie’s stomach clenched.

“It’s not as though dead tweakers are anything new around here,” said Alvarez. “Santa Fe gets a lot of runaways. Some are on drugs when they show up; others find them.”

Her hands tightened on the edge of the table. “It doesn’t help that we’ve got our own local dealer—maybe meth cook, too—with a sideline in artifacts. Trades drugs for pots and whatever else they bring in, which is plenty.” Her knuckles showed pale. “From looting my site!”

Joshua shot Cassie a here we go again look.

“Just this morning,” Alvarez continued, “I finally got a chemical analysis of the clay from one sherd. Not what I was expecting. Basalt, a lot of it—and even armalcolite.”

Cassie frowned. “Armalco-what?”

“It’s a mineral. Pretty rare. And the first place they found it was the moon.”

Joshua looked dubious. “Moon pots?”

Reaching into her backpack for McAllister’s field journal, Cassie flipped to the petroglyph sketches. Moon-flyer sketches. Selecting the one carrying a circle, she pushed it across the table to Alvarez.

In the silence that followed, Cassie felt sweat drying cold on the back of her neck.

Then Alvarez exhaled sharply.

“That’s . . . interesting.” She picked up the battered notebook. “I’d like to borrow this tonight, if you don’t—”

“I made you copies.”

Before Alvarez could complain, Cassie retrieved her property and stowed it away. If the archaeologist wasn’t happy with the manila envelope she got back, she wasn’t showing it. Much.

“I’ll still need the original when I write up my field notes. The ceramics we’re finding here are unique. Not just that clay, but the black-on-white pattern.”

Cassie nodded, trying to look as if she knew more than she probably did.

“There’s something else about them,” Alvarez added. “But only the sealed ones, the ones with the webs.”

Disquiet crossed her face. “Or whatever that is.”

“It happens when you touch them.” Joshua’s voice dropped. “There’s some kind of tangible reaction—”

“More than that. And it happens in your head.”

The security guard and the archaeologist stared at each other. Cassie got the distinct impression that they’d both had this experience separately. And hadn’t shared it afterwards, for whatever reason.

She could think of a few.

“I could show you a cache,” Joshua finally said. “It was fine last night, anyhow. I don’t think the looters know about it yet—”

He stopped short. “If that’s OK, Dr. Alvarez?”

Alvarez glanced back up toward the parking area before replying.

“Go ahead,” she said. “But keep an eye out. We can’t afford to keep losing pots.”

4

THEY WERE SEVERAL MINUTES INTO THE CANYON before Joshua Yellowtail spoke again. Looking up at the shadow-pocked walls, Cassie wondered what else he hadn’t put into that letter.

Or had been told to leave out?

Zia House’s director had been chasing something unique, too—and she’d caught it. Or it caught her, the way the Outside did when people weren’t paying attention. When they thought they’d found some private exception to the rules of this world, but it was still OK, all perfectly natural—

“I said, have you got a flashlight?”

Cassie gave Joshua a guilty half-smile. “In my backpack.” Her amusement faded. “But I’m not going into any dark holes until you tell me what’s going on with Dr. Alvarez. Why’d she want me down here, anyhow?”

Joshua took a careful look up and around.

“Kit Baker.” He shrugged. “And tenure.”

Cassie winced. Just when I thought it couldn’t get any better.

“She thinks Kit’s feeding information to pothunters?”

“To somebody working with pothunters. Maybe that dealer she was talking about—Len Mason, I think his name is. Serious bad guy. I’ve run him off once or twice.”

He hesitated. “Not sure why she’d be doing it, though she and Dr. Alvarez don’t exactly get along.” A longer pause. “But she knew about that new find spot last month. And the one in the picture I sent you.”

Cassie bit her lip.

“Do I even want to know about the tenure part?”

“I don’t even know about it, officially. But one thing you learn working security is to keep your ears open.”

And one thing she’d learned about frostbite was to trust it.

Jupe and Juno hadn’t liked that sherd one bit. McAllister’s notes and Alvarez’s chemical analysis of another sherd dovetailed a little too well. Now here she was, about to go headfirst into a cavate with who knew how many whole pots— and touch them.

Resisting the urge to check the small .38 under her shirttail, Cassie kept walking. Joshua Yellowtail was Frank’s nephew, after all. Not likely to lead her into danger.

But she wouldn’t have figured him for stashing an inconvenient body, either.

A few minutes later, he stopped and pointed at the canyon wall just above her head.

“Maybe that’s why looters didn’t find it first. Not real easy to get at, though there must have been a ladder there once. Or handholds that eroded.”

Cassie frowned up at the dark opening.

“So how did Dr. Alvarez even think to check it?”

“She mentioned hearing something strange in the wind here.” He shrugged. “All I know is, she hasn’t told any of her students—and she always brings her own stepladder back at the end of the day.”

Cassie took off her backpack and removed the flashlight, plus a pair of work gloves. Then she jumped up for the cavate’s edge, managing to find handholds on her second try. As she scrambled for footing on the wall below, Joshua’s interlaced hands gave her a boost.

“Thanks.”

He passed the flashlight up. In its strong beam, the cavate looked larger and taller than it had from outside, its ceiling nearly high enough for her to stand. Or at least crouch. Moving carefully, she shuffled toward the back.

A mineral tang of rock and dust filled her nostrils. Nothing else. So far, so good—

Cassie froze. The few pots nestled at the back of the cavate had more webbing across their mouths than the ones in Joshua’s photos. It looked fresh, too; silvery-moist in her flashlight beam.

As for the pots themselves, they actually were black-on-white. Not the worn gray-on-chalk seen in museum cases, or the dingy charcoal and tan of sherds she’d been tempted by at trading posts. And no chips or cracks she could see—from a distance.

Up close, the canteen-style vessels were even more disturbing, as though their Anasazi creator had just set them down and walked away. Alvarez was right about the design, though. Beneath these simple crosshatchings and spirals, diamonds and saw-toothed lines, something else had left its mark.

And all those spirals dark galaxies flecked with suppurating stars—

Gritting her teeth, Cassie pulled off her left glove.

Then, before she could think about it, she pressed her palm against the nearest pot.

At first, she felt nothing but the cool strangeness of the clay. The vessel beneath her hand curving . . . outward. Outward toward the thinnest edge of space, where all laws of small blue spheroids shattered against the inchoate Beyond.

Where the only human sound was a soul-deep shrieking.

5

BACK ACHING AFTER A LONG MORNING OF CATALOGING potsherds, Cassie swore under her breath as she headed up the trail. No surprise that she’d forgotten her lunch. After getting back from her little hike yesterday afternoon, she’d barely managed to drive herself safely to Santa Fe. Checking into her hotel had been its own adventure.

Sleep hadn’t come until the small stark hours. When it had, her dreams had driven her back to the room’s single chair, where she’d paged through McAllister’s journal until sunrise.

His comments on the moon-flyer story drew most of her attention. What a flood in Vermont had to do with tourist rumors in New Mexico, she couldn’t imagine—until she rechecked his four petroglyphs. The descriptions in those 1927 articles didn’t mirror what he’d drawn, but they’d been close. There was no good reason for that. No explanation at all for the object held by one “flying” glyph.

At least, none she wanted to consider after touching that pot.

Cassie wiped her left hand on her jeans and kept walking. She’d lost her appetite, but soda from her cooler would make a change from the tepid water Alvarez provided. Even that was in short supply: the archaeologist had taken several bottles when she and her stepladder headed out this morning. A last wave of monsoon rain was on its way, she’d heard. No time to waste at her new favorite cavate.

If Joshua had told her about yesterday’s visit, Alvarez hadn’t mentioned it. Cassie wasn’t about to, either. Not with Kit hanging around poking at her laptop, long after she should have—

“. . . I’m almost out, dammit. And you said you’d get me some.”

Kit’s voice drifted down from the parking area ahead. She was on her phone, Cassie guessed: the signal was a lot better up there, though still not great.

She wasn’t sounding that great, either. Cassie had noticed her looking shaky most of the morning—hung over, she’d assumed. Or coming down with something. Or . . . ?

Edging into a stand of pines beside the trail, Cassie kept listening.

“No, not until the end of the month!”

Whatever Kit was hearing on the other end, she wasn’t liking it.

“You know that’s not going to work, you bastard.” Long silence. “Look, maybe I can find you something. Another cache—”

Cassie’s teeth found her lower lip. Joshua was right: the pothunters, or someone running them, were getting inside help. And not for the first time, either.

“So what am I supposed to do, tail her? That would work real well.” Kit’s voice was raw. “All I know is, she takes a ladder out sometimes. If I find out more—”

Her voice cut off. After a few minutes—and another expletive—she headed down the trail, veering close to Cassie’s hiding place.