Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

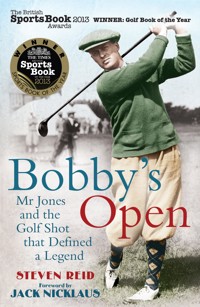

TIMES BRITISH SPORTS BOOK OF THE YEAR 2013 25th June 1926. Royal Lytham & St Annes Golf Club is hosting the world's oldest and most prestigious golf tournament - The Open Championship. A stellar field of players has assembled from both sides of the Atlantic hoping to claim victory, including Walter Hagen, Harry Vardon and a rising young amateur from the USA, Bobby Jones. Already a winner of the US Open and US Amateur Championship, Jones has yet to win a Major event on British soil. To do so now would set him on a path of unrivalled achievement and into the history books as the greatest amateur golfer the world has ever known. As the competition boils down to the penultimate hole on the final day, Bobby must hold his nerve to pull off a miracle recovery shot that will fire his reputation - and that of the golf course - around the world. Bobby's Open is the inspirational story of a golfing legend and one of the game's defining contests. Steven Reid blends social history with sporting biography to portray the most famous sportsman of his time, examining why Jones was so adored and the cruel price he ultimately paid for his genius.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 342

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Printed edition published in the UK in 2012 by

Corinthian Books, an imprint of

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.co.uk

This electronic edition published in the UK in 2012 by

Corinthian Books, an imprint of Icon Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-190685-031-9 (ePub format)

ISBN: 978-190685-032-6 (Adobe ebook format)

Sold in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Published in Australia in 2012

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in Canada

by Penguin Books Canada,

90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3

Distributed to the trade in the USA

by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution,

The Keg House, 34 Thirteenth Avenue NE, Suite 101,

Minneapolis, MN 55413-1007

Text copyright © 2012 Steven Reid

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in New Baskerville by Scribe Design

Dedicated to my parents: to my father Donald for the infinite patience and tolerance he showed whilst introducing me to golf and to my mother Joan for her endless giving.

Contents

Title page

Copyright

Dedication

List of figures and plates

Foreword

Preface

1. ‘My, but you’re a wonder, sir!’

2. On genius and temperament

3. The first crossing

4. The transformation

5. On strain and destiny

6. The second crossing

7. The story of St Anne’s

8. A glimpse into the hall of Valhalla

9. Final preparations

10. Meet the players

11. The first day

12. The second day

13. The final day

14. A teaspoonful of sand

15. The final hole

16. The presentation

17. Mr Jones turns sleuth

18. Free, at last!

Bibliography

Sources, notes and acknowledgements

Appendices

A. Final leader board, 1926 British Open Championship

B. The course at St Anne’s then and now

C. Bobby Jones and the Claret Jug puzzle

D. Tommy Armour on Jones

E. The Berrie portrait

F. Just one more time – Jones visits St Anne’s in 1944

Index

Plate section

List of figures and plates

Images in the text

Figure 1. The 1934 survey of the seventeenth hole at Royal Lytham and St Anne’s.

Figure 2. Jones’s reply of 12 June 1958 to a letter he had received from the secretary of Royal Lytham and St Anne’s.

Figure 3. The reply by the secretary, dated 21 August 1958.

Figure 4. Jones’s reply of 27 August 1958.

Figure 5. Letter from Jones to the Royal Lytham and St Anne’s club, dated 14 September 1960.

Figure 6. Jones’s letter of 17 March 1953 to Sir Ernest Royden about the Berrie portrait.

Plate section

Plate 1. Mr R.T. Jones Jnr by J.A.A. Berrie.

Plate 2. Wild Bill Melhorn and Bobby Jones.

Plate 3. Mr George Von Elm.

Plate 4. The unique and irrepressible Walter Hagen.

Plate 5. Tom Barber of Cavendish.

Plate 6. Jones driving, watched by hatted spectators.

Plate 7. Jones putting at the old thirteenth green, now the fourteenth.

Plate 8. Wild Bill Melhorn tee shot at a short hole, probably the fifth.

Plate 9. Hagen’s tee shot to the fifteenth in the third round on the final day.

Plate 10. Jones and Al Watrous leave the first tee in the final round.

Plate 11. Watrous drives at the third hole in the final round.

Plate 12. Jones tees off at a short hole on the final day, watched by his caddie Jack McIntire.

Plate 13. Crowd control, 1926 style – the gallery follow Watrous and Jones down the sixth hole in the final round.

Plate 14. Jones plays a pitch to the sixth green.

Plate 15. Watrous watches Jones play to the seventh green.

Plate 16. Jones watches the first Watrous putt on the seventh green.

Plate 17. The first wobble by Watrous, at the tenth hole in the final round.

Plate 18. The final green.

Plate 19. Jones, having come close to finding the bunker behind the last green, plays his penultimate stroke.

Plate 20. The final putt.

Plate 21. Awaiting the presentation ceremony, the winner signs autographs.

Plate 22. Hagen presents a nonplussed Jones with an outsized niblick.

Plate 23. Jones makes his acceptance speech.

Plate 24. Jones with Norman Boase, Chairman on the R&A Championship Committee and a cheerful Hagen behind.

Plate 25. Hero worship after the presentation, including eleven helmeted policemen (or ‘bobbies’).

Plate 26. The exhausted champion.

Plate 27. The photograph submitted to Jones in 1958 asking whether this was the wonder shot at the penultimate hole (see chapter 17).

Plate 28. Another photograph, of exactly the same shot (in chapter 17 this is shown to have been played at the fourteenth hole in the third round).

Plate 29. The plaque created at the suggestion of Henry Cotton to mark the spot from where the ‘immortal shot’ was played.

Plate 30. Jones in USAAF uniform before the Berrie portrait in the clubhouse.

Foreword

by Jack Nicklaus

In Bobby’s Open there are two chief characters: one a golf course; the other one of history’s most outstanding golfers. As I have had the privilege of knowing both of them, I was delighted to be invited to contribute a foreword.

The golf course is the links layout of the Royal Lytham and St Anne’s Golf Club. In 1963, and at the age of 23, I was on the brink of winning my first British Open when my youthful inexperience, combined with the fiendishly difficult last four holes at Royal Lytham denied me that chance. A week later, I won my first PGA Championship but the lessons learned at Royal Lytham dwelled with me for years to come. During that week and subsequent visits for Opens and the Ryder Cup, I came to greatly admire and respect the way the course tests a player’s complete game. Although I never won an Open there, I came to recognise the thorough examination it presents to a player aspiring to win there.

The golfer is the unique and iconic Bob Jones.

I grew up idolising Mr Jones, first learning of his name and achievements from my father and other members at Scioto Country Club, the club in Columbus, Ohio, where I not only learned to play the game of golf as a boy but where Mr Jones won the 1926 US Open. While my awareness of him was keen due to the stories that had endured more than a quarter-century since that victory, my first meeting with Bob Jones came when I was fifteen years old and playing in the US Amateur in 1955. I remember that as I was walking off the eighteenth green of my final practice round on the James River Course at the Country Club of Virginia, someone called me over and said, ‘Mr Jones would like to meet you.’ I walked over, and he said, ‘Young man, I’ve been sitting behind this green here for the last couple of hours, and there have been only a few people reach this green in two, and you were one of them. I wanted to congratulate you.’ That evening, Bob Jones was the speaker at the banquet and at one point he said to me that he was going to come out and watch my first match. The nerves that accompany a fifteen-year-old playing in his first national amateur were already a bit exposed, especially when facing the formidable Bob Gardner, who went on to play in the Walker Cup, World Cup, and many other international amateur events. I actually had Bob down one hole after ten holes, despite anxiously awaiting the arrival of Mr Jones. All of sudden, coming down the tenth fairway, was Bob Jones. All I could think was, ‘Oh my goodness.’ He followed me for three holes, during which I went bogey-bogey-double bogey and went from one up in my match to two down. Sensing that his presence was affecting my game, he showed great consideration and thoughtfulness by turning to my father and said, ‘I don’t believe I’m doing young Jack much good. I think I’d better get out of here.’ Although I lost on the last green, I took away a great impression of his sensitivity and concern.

I had the pleasure of seeing Bob Jones on many occasions after that. The most memorable, of course, was each time I went to Augusta National – a place that has always been very special to me, a mystique only enhanced by the history and the aura of Bob Jones, and what he meant to Augusta National and The Masters Tournament. I never actually saw Bob Jones play golf, which is a source of personal regret. Yet from film footage and the mental images I have created from so many conversations with people who knew him well, it is clear he had a swing that could be described as a work of art. Just as important as his technique was his ability to compete and win under the immense pressure he imposed on himself.

So much has been said, written and celebrated about Bob Jones, but in these pages there is a new overview on how he overcame self-admitted problems to achieve such greatness and become a standard by which many other champions, including my own career, were measured. The entire 1926 Championship is brought back to life in these pages. The book allows readers to travel with Bob Jones as he struggled with his game before finally hitting that justly celebrated shot at the 71st hole. It was a shot that summed up Jones as a man as well as a golfer.

During my early years playing in the Masters in the 1960s, my father and I used to treasure the time we spent talking with him in the Jones Cabin. He thought and cared deeply about the game, and with the publication in this book of the previously unknown letters from Jones to Royal Lytham, written in 1958, there is a glimpse into the keen enquiring mind that stayed with him despite his illness and an awareness of his enduring humanity.

Bob Jones was in so many ways a remarkable golfer and man. This book rightly presents him as such to the reader of today.

Preface

This is not just another book about Bobby Jones. Let’s be honest, there is no need for ‘just another book’ about Bobby Jones. Instead it fits into a new genre of ‘Openography’, telling the story of how one Open Championship unfolded and evolved. In the case of the 1926 British Open played at Royal Lytham & St Anne’s Golf Club, this account is also inevitably about one golfer, Robert Tyre Jones Jnr.

In examining how he came to win at St Anne’s, it is revealing to review Jones’s first transatlantic crossing and to trace in detail how he solved his earlier problems with temperament. From 1926 onwards he was to become the perfect winning machine and established a record that will never be equalled.

In the qualifying round for the British Open, Jones played at Sunningdale what is judged by many to have been the most nearly perfect round ever completed. Contemporary accounts give a flavour of the impact on those fortunate enough to have witnessed it.

The newspaper accounts of the time give a full account of the happenings during a memorable championship at St Anne’s, encapsulated by the famous shot from sand at the 71st hole that gave Jones his victory.

The discovery of previously unknown correspondence between the club and Jones in 1958 reveals the extent of his inquiring mind that stayed alert despite his crippling illness.

As it is hoped that the book will be of interest on both sides of the Atlantic, the Open (as it is known to British readers) is described throughout as the British Open, notwithstanding the dismay this will generate in traditionalists on one side of the Atlantic! For similar reasons the Amateur will be described as the British Amateur. Bernard Darwin will be spinning in his grave.

In adult life, Jones disliked being called Bobby, being known as Robert by his mother, Rob by his father, Bob by his friends, Bub by his grandchildren and occasionally Rubber Tyre by a playful O.B. Keeler. It is because he was universally known by the golfing public as ‘Bobby’ that he will be referred to as such in this work.

The place Jones came to occupy in the world of golf is delightfully revealed in the account given by Sidney L. Matthew in The Life and Times of Bobby Jones. He describes the experience of Jones’s long-standing friend, Robert W. Woodruff, when playing the Old Course at St Andrews. He was rather pleased when at the fifth hole he reached the front of the par-five fifth green in three shots. Turning to his rather ‘crusty old caddie’ he was foolish enough to say, ‘That was three pretty good shots, don’t you think?’ The caddie responded, ‘When I caddied for Bobby Jones, he was here in two.’ Inadvisedly the golfer mischievously retorted, ‘Who’s Bobby Jones?’ Woodruff recounted how ‘The caddy could only stare at me, back off a step, then another, taking the golf bag off his shoulder and laying it on the ground as he continued to pace still further backwards incredulously. The caddy then turned towards the clubhouse and he never looked back.’ Woodruff recalled, ‘And he didn’t come back.’

Ecce homo – behold the man.

Steven Reid, St Anne’s 2012

CHAPTER ONE

‘My, but you’re a wonder, sir!’

It is not often that anything good comes out of the mouth of a caddie, but from time to time an utterance captures an occasion perfectly.

By 1936, it was getting on for six years since Bobby Jones had retired from competitive golf. He had reached the summit of the game by winning all four major championships – the British Open, British Amateur, US Open, US Amateur – in 1930, thereby triumphing in the events that made up what had been first described as the Impregnable Quadrilateral and subsequently, in more familiar terms, as the Grand Slam.

He had crossed the Atlantic once more with his wife Mary to attend the 1936 Olympics, held in Berlin as clouds gathered over Europe. His fellow travellers were the writer Grantland Rice and Robert Woodruff, along with their wives. After the sailing across the Atlantic, they broke their journey to Germany by spending a few days in Britain. Although Jones’s game was indifferent, he had brought his clubs with him and accepted Woodruff’s invitation to spend some time in Gleneagles, Scotland. To his delight his golf improved and after shooting two rounds of 71 his spirits lifted.

At dinner that evening, Jones’s mind wandered and he felt the call of the ‘Old Lady’ of St Andrews. Surely he could not drive past the Old Course and not return to pay his respects? Accordingly a chauffeur was dispatched to enter his name and that of Woodruff for an afternoon round. The next day, Jones and Woodruff enjoyed a lunch with Norman Boase, then captain of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club (known to golfers everywhere simply as the R&A). Ten years earlier Boase had been chairman of the R&A’s Championship Committee that had organised the holding of the Open Championship at Royal Lytham & St Anne’s and by happy coincidence had led the young Jones out to the presentation ceremony after his win there.

At St Andrews, Boase had arranged for Willie Auchterlonie, winner of the Open in 1893, and Gordon Lockhart, professional at Gleneagles, to play with Jones and Woodruff. When Jones came down from lunch, he was concerned to see a large crowd of some 2,000 was around the first tee. Perhaps he had inadvertently chosen a day when some large tournament was being played? It was worse than that – he realised that the crowd was there to watch him!

Someone had noticed the name R.T. Jones Jnr on the drawsheet. The word had spread like wildfire through the auld grey town. Thousands abandoned their tasks and wandered down to the course. Shopkeepers heard the news and many closed up for the day. One left a note on his shop door explaining why his shop was mysteriously closed. The note simply said, ‘Bobby’s back.’

As the match got underway and the golfers headed away from the clubhouse, the crowd continued to grow and Rice estimated that it reached 6,000. Without any marshalling, an element of chaos was inevitable as the match struggled to make its way out down the course. Thankfully the crowd lifted Jones’s game and after birdies at the second, the fifth and the sixth, he came to the eighth tee where he hit a soft four-iron shot that rolled back the years. Hit with a delicate fade, the ball cut around the mound that protected the pin and came to rest just eight feet from the flag. What happened next had remained a personal internal memory with Jones, until he revealed it in his book Golf is My Game published in 1961. Perhaps sensing the escalating problems with his health and aware that this book was likely to be ‘my last utterance on the subject of golf’, he overcame his innate modesty to share that experience with others: as he put the club back into the bag, the caddie, a young man in his early twenties, said to Jones under his breath, ‘My, but you’re a wonder, sir!’

* * *

On 17 March 1902 unto the world of golf Robert Tyre Jones Jnr was given. From an early age and until he retired from competitive golf at the age of 28, he gave and gave to the world of golf until he could give no more.

There are sufficient accounts of his early life to preclude the need for yet another here, but there are some happenings and influences that should be mentioned because of the part they played in producing this unique golfer. During his playing career he indicated his perception that predestination was applied to many events. Perhaps it was preordained that personalities and events should combine to create the setting in which his talents could develop and flourish.

Bobby’s middle name ‘Tyre’, with its Old Testament and other overtones, was first given to Bobby’s grandfather, Robert Tyre Jones. Born in 1849, here was a man, generally known as ‘R.T.’, with a considerable physical presence. He was 6′ 5″ tall, for that time a remarkable height. He had known hard times in the aftermath of the American Civil War, trying to help on his father’s farm and in his cousin’s general store in Northern Georgia. Believing that the nearby town of Canton could support a general store of its own, he committed his entire savings of $500 to the process of creating one. From that successful beginning, he was involved in the setting up of the Bank of Canton and then created the Canton Textile Mills that were to make his fortune. A man of strong faith, he served for forty years as Superintendent of the First Baptist Church in Canton and shunned ‘womanising, smoking, cursing or drinking.’

Bobby’s father was given the forenames of Robert Permedus and subsequently became widely known as ‘The Colonel’. He was a more than useful baseball player and were it not for his own austere father, he would have signed a contract to play for the Brooklyn Club in the National League. A parental veto came into effect with the words, ‘I didn’t send you to college to become a professional baseball player’ and instead a career was forged in the law. When R.T. was told that his son was a good baseball player, his retort was that ‘You could not pay him a poorer compliment.’ R.T. never saw his son play baseball.

R.T. carried his views on sport on to the next generation until he softened in later life. When playing in the 1922 US Amateur, Bobby received a telegram from his grandfather which said, ‘Keep your ball in the fairway and make all the putts go down.’ This glimmer of support revealed a major shift in attitude and had a considerable emotional impact on the young golfer. Disapproving strongly of playing any sport on the Sabbath, he eventually said to Bobby, ‘If you must play on a Sunday, play well.’ When Bobby returned to New York after his win in the 1926 British Open, he was met by his young wife Mary and his parents. Also there was R.T., who was at pains to point out to the press that he happened to be in New York on business and while there dropped down to see what was taking place. No one was duped.

In 1927, well-intentioned members of Atlanta Athletic Club raised $50,000 and gave it to Jones at a celebratory dinner to allow him to purchase his own house. After first accepting it, Jones felt it might threaten his amateur status and put out feelers to the United States Golf Association (USGA). Their response was that it might well warrant examination. A nod was as good as a wink and he returned the cheque. His short-term despondency at no longer being able to set up his own home evaporated when R.T. lent his grandson the exact amount. His austere side had not completely gone as he laid down strict terms: there was to be repayment – but only at the rate of $1 per year!

Perhaps it was inevitable that the Colonel was the opposite of his father. He saw life as something to be enjoyed rather than endured. Away from parental awareness he cursed, drank and told adult jokes. He took into adult life a resolve that his offspring would never be denied the opportunity to develop whatever sporting aptitude they might have.

The Colonel’s wife, Clara Thomas, was short and slightly built, but not lacking in character. Calamity struck when their firstborn William Bailey Jones struggled in his early life with protracted vomiting and weight loss. He died when aged three months and Clara bemoaned the poor medical care provided in the small town of Canton. The cause of William’s vomiting may well have been a condition called pyloric stenosis. If so, her views were valid as that condition would have been curable by a small operation. When she became pregnant again, she urged her husband to move to Atlanta to find better medical cover. Perhaps to get away from the oppressive influence of R.T., he needed little urging.

Soon after reaching Atlanta, the Colonel began work for the expanding Coca-Cola Company. As well as lamenting the sporting opportunities he was denied, he was always disappointed that he had not been given his father’s middle name. Clara fell pregnant again and this child was named Robert Tyre after his grandfather.

Weighing only five pounds at birth, the newborn gave his parents continuing concern with a ‘delicate stomach’. He was taken to a variety of doctors but apart from suggesting a diet of egg whites, pabulum and black-eyed peas they had no useful suggestions. By the time he was six he was described as ‘an almost shockingly spindling youngster with an oversize head and legs with staring knees. Few youngsters at the romper age have less resembled, without being actually malformed, a future athletic champion.’

It was to address this worrying equation that the Colonel took his family to East Lake Golf Club, Atlanta for the summer and gave the boy his first exposure to golf. Though he never had a formal lesson, Bobby just watched the balanced rhythmical swing of the Scottish club professional Stewart ‘Kiltie’ Maiden who had been brought over from Carnoustie. He was also fortunate to find himself playing with two other talented youngsters, Perry Adair and Alexa Stirling. Within a few years Bobby’s natural propensity to imitate produced a latent talent that was to flower over the decades that followed. He was greatly helped by his innate ability to mimic swings he watched. When friends of his father were at the house, he was often called upon to imitate various adults. Jones recalled that Judge Broyles never seemed to get as much fun out of the rendition of his own foibles as did the others present. Copying Maiden’s flowing swing was a more fruitful strategy. By the time he reached his early teens it was clear that here was an exceptional talent.

During the First World War Bobby played in many exhibition matches, raising considerable sums for the war effort. The first series of matches were with his friends from Atlanta: Perry Adair, Alexa Stirling and Elaine Rosenthal. Golf for the four youngsters was simply fun and to be enjoyed. Subsequently, Chick Evans who as an amateur had won the US Open and the US Amateur in the same year in 1916, invited the sixteen-year-old Jones to partner him in a series of matches against leading professionals, further helping the relief funds.

Not only was he a golfing prodigy, Jones’s educational achievements were sustained and considerable. In his later teens he entered Georgia Tech to study mechanical engineering. At first glance this might be seen as an unexpected choice of college and course, but Perry Adair being there may have been a factor. Although there was no family pattern of studying engineering, the subject may well have appealed to Jones’s enquiring mind. Beyond engineering, the course included mathematics, geology, physics, chemistry and drawing. He completed his four-year course, finishing in the top third of his year, scoring marks in the 90s in English, maths and geology and in the 80s in chemistry, electrical engineering and physics.

Having graduated as a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering, he resolved to apply himself to the humanities and enrolled at Harvard to study English. He marked his arrival by setting a new record for the golf course at the Charles River Country Club. Having played college golf for Georgia Tech, he was ineligible to play for Harvard, but cheerfully took on the post of manager and coach. As he himself said, ‘How else was I going to get the Crimson “H”?’ He applied himself diligently to his studies, recalling spending all his surplus allowance in the bookstores ‘around Scolley Square or, when I was a little better heeled, in Lauriat’s basement.’

While there his golfing opportunities were stifled and it has been suggested that he applied for leave to play in the 1923 British Amateur, but permission was denied as it would have conflicted with his exam schedule. Even with minimal exposure, his level of play was maintained. On one occasion he played against the best ball of the entire six-man Harvard team and won. He pursued his studies on an accelerated timetable, with course work in German, French and British history. Happenings in Continental Europe 1817–1871 had to be tackled, as did Roman history. His classes encompassed the writings of Dryden, Shakespeare and Swift and aspects of Comparative Literature and Composition. He emerged with his valued Bachelor in Arts in English Literature.

Jones then spent a rather unsettled time in the real estate business, again perhaps as a means of keeping in touch with Perry Adair. During the summer of 1926, Jones had a realistic chance of winning the British Amateur until, afflicted by an acute neck spasm, he lost in the sixth round. He then won the British Open and US Open and only lost in the final of the US Amateur to George Von Elm, who had finished third in the British Open a few weeks earlier. His achievements in that year were only a little way behind those of the 1930 Grand Slam. Sensing that real estate was not for him, he enrolled in the autumn of 1926 in the Emory law school. His original plan was to complete the three-year course and he applied himself well to his studies, being placed second out of the 25 students after the first year.

His instructor in contracts, Professor Quillian, considered Jones to have ‘one of the finest legal minds of any student I’ve ever known.’ Towards the end of the autumn term of 1927, he entered himself for the Georgia bar examination to provide himself with a measure of his progress. Perhaps a little to his own surprise, he passed and as this entitled him to take up the law immediately, he was able to pass up on the option of completing the rest of the course at Emory.

Of more interest than his ability to satisfy examiners was the breadth and depth of his intellect and the enquiring nature of his mind. He loved opera, for example; and while travelling to the first Walker Cup at the National Golf Links on Long Island, his reading material on the train was Cicero’s Orations Against Cataline. Vexed at his tendency to deprecate his golfing ability, Jones once said, ‘this bird Cicero was a long way from hating himself. I wish I could think as much of my golf as he did of his statesmanship. I might do better in these blamed tournaments.’ Sports writer Grantland Rice pointed out how ‘in starting out for a Championship, [Jones] might be found with a Latin book or a calculus treatise, with all thought of golf eliminated until he reached the field of battle.’ At other times he would be found discussing Einstein and the fourth dimension. His practice for the 1923 US Amateur at Flossmoor was wretched, so his strategy between the two qualifying rounds on the Saturday and the Monday was to stay in his bed in the hotel on the Sunday, reading Papini’s Life of Christ.

Jones’s own writings revealed the rich vein of thinking from which he drew his text. He did however admit that the creation of written work did not come easily. Corresponding with golf writer Pat Ward-Thomas he revealed, ‘I am not one of those fortunate persons who can sit down before a typewriter and spill out words that make sense. The act of creation on a blank page costs me no end of pain.’

Broadcaster Alistair Cooke, in a review he entitled ‘The Missing Aristotle Papers’ on the instructional articles that made up Bobby Jones on Golf, revealed his admiration for the quality of Jones’s writing. He wrote:

Jones’s gift for distilling a complex emotion into the barest language would not have shamed John Donne; his meticulous insistence on the right word to impress the right visual image was worthy of fussy old Flaubert; and his unique personal gift was to take apart many of the club clichés with a touch of grim Lippmannesque humour.

Fuelled by his genuine modesty, Jones wrote back to Cooke with the tongue-in-cheek comment, ‘Offhand, I can’t think of another contemporary author who has been compared in one piece to Aristotle, Flaubert, John Donne and Walter Lippmann.’

Looking back, his grandson recalled how Jones would ‘go out on a fishing boat with his friend, Charlie Elliott, the editor of Outdoor Life and for hours they would talk about syntax, sometimes English, sometimes Latin.’ However it should not be deduced from the foregoing that Jones was too serious about life or himself. Charles Price points out that ‘He was not the least bit calculating or priggish. He smoked to excess on the course, drank corn whisky off it, swore magnificently in either place, and could listen to, or tell, an off-color story in the locker-room afterward. He was spontaneous, affectionate, and loyal to his friends, all of whom called him Bob.’

The remaining piece of the jigsaw that allowed his genius to find its full expression was Oscar Bane ‘Pop’ Keeler. Originally a journalist, he not only became Jones’s mouthpiece to the world at large but more crucially a source of wise counsel and a steadying influence. During the early years, repeated disappointments threatened to weaken the young golfer’s resolve and it took all of Keeler’s guile to keep young Bobby’s spirits up.

During the period of his playing career when he won championship after championship, Jones was shielded by Keeler from the Press. The reporters got their material from the mouth of Keeler, an arrangement which in many ways suited them as their work was already half done. What is more important, Jones was spared the exhausting process of being interrogated and the unsettling experience of being asked to analyse what he was doing to achieve his successes.

Keeler was also an intellectual stimulus to Jones as they travelled and roomed together. Best viewed as a benevolent uncle, O.B. brought the best out of his young ward and made long train journeys pass quickly. It is probably true to say that without Keeler the playing record of Jones would have been diminished.

CHAPTER TWO

On genius and temperament

‘Talent hits a target no one else can hit: genius hits a target no one else can see.’

ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER

Bobby Jones was a genius at golf.

At first glance it might appear to be a little over the top to suggest this. However, not only does the contention warrant serious consideration, it deserves acceptance. Such a suggestion has been made at least twice before. The first located reference is the New York Times issue of 26 June 1926 which, quoting from the correspondent of the Observer, stated:

There is no parallel in the history of golf, and I do not suppose there ever will be again. Mr Bobby Jones is just a genius, and they are not born every day.

The second is by golf writer Charles Price, who revered Jones as a golfer and as a man. He wrote:

The explanation for Bobby Jones’s astounding golf is quite simple. He had a genius for the game.

It is possible to be a genius as an adult after an unremarkable childhood and it is equally possible to be a child prodigy and thereafter mundane in later life, on occasions after a spectacular burnout. There is also a cohort of individuals who are both child prodigies in their earliest years and geniuses as an adult, the former phase flowing irresistibly into the latter. Jones was such an individual.

In a child prodigy, one sees someone who at a very early age masters a difficult skill to the level of an adult. At the age of five Mozart was composing minuets. Aged six he was performing in concerts on harpsichord and violin. By nine he had composed his first symphony and at the age of twelve his first opera. By the time Prokofiev entered the St Petersburg conservatory at the age of thirteen, he had a portfolio of four operas, two sonatas and some piano pieces. William Rowan Hamilton, later a leading mathematician, read Hebrew by the age of seven and by the age of twelve had studied Arabic, Persian, Greek, Latin, Syriac, Sanskrit and four other foreign languages.

A child prodigy displays one key feature of genius that was stressed by Immanuel Kant: the ability to independently arrive at and understand concepts that would normally have to be taught by an adult. This is how Jones came to golf – without lessons and simply by grafting his own perception of the essence of golf onto what he saw East Lake’s Stewart Maiden do. This aspect sets him apart from every other golfer before or since. From his play in his early years, Jones was clearly a child prodigy, not just from his play and achievements, but also from the way he acquired a game and swing that was all his own.

He had little time for practice as a discipline, though he would go on to the practice ground on occasion if he felt a particular matter needed to be addressed. Having done so to his satisfaction, he would then leave. His golf was instinctive and intuitive. He spent only three months in each year in what might be considered competitive golf. During the part of his golfing career referred to by Keeler as the ‘seven fat years’ from 1923 to 1930, he only played in five tournaments other than the Majors – and won four of them! In the cauldron of the fiercest competition, from standing up to the ball to hitting his shot was timed at three seconds. This is to be contrasted with the laboured mechanics of the players of today.

In the period that Keeler described as the ‘seven lean years’ between 1916 and 1923, Jones underwent a gradual evolution from child prodigy into the genius he was later able to express in the seven fat years. To paraphrase Owen Meredith, Earl of Lytton, talent does what it can, but genius does what it must. Jones knew that he had to scale heights beyond the reach of others. However, in the early lean years he had a real problem that prevented this genius from being expressed – the destructive effect of his own temperament. Because of its relevance to his subsequent development in the run up to the British Open at Royal Lytham & St Anne’s, this problem merits further examination. The few reported instances of ill temper are inevitably just a small fragment of what must have been a consistent aspect of his golfing excursions.

Some have suggested that the problems experienced by the young Jones were simply those of a hot-headed youth who was taking his time to find his equilibrium, but clearly they were based on something much deeper than that. In his earliest days on the makeshift two-hole ‘course’ near the house he stayed in at East Lake, he would at times dance with rage in the middle of the road if a shot failed to meet his expectations. And this was at the age of six.

The inner force that created Jones’s instinctive ability also created a furious and destructive energy within. One of the other youngsters with whom he played was the exceptionally talented Alexa Stirling. She later recalled:

Let him make one poor shot and he’d turn livid with rage, throw his club after the ball, or break it over his knee, or kick at the ground and let out a stream of very adult oaths. As I grew into my teens, Bob’s temper tantrums began to embarrass me. It was perhaps amusing to see an eight-year-old break his club when he made a bad shot, but not so amusing when he was twelve or thirteen.

Bobby may have learnt colourful language from the adults with whom he played, but he had little control over himself and his ability to suppress such expressions when he knew he ought to. On another occasion Alexa, playing with her father, came across Jones who had just played a bad shot. He threw his club and swore aloud. This greatly offended Alexa’s father who said to Jones, ‘Young man, don’t you know better than to use language like that in front of a lady?’ Alexa described how her father ‘took me by the hand and marched me off the course.’ She was not allowed to play with Jones for two years.

In 1915 Grantland Rice watched the thirteen-year-old Jones in the company of Alex Smith and Long Jim Barnes, both of whom subsequently won the US Open. After Jones ‘violently repositioned’ his club in his bag after a shot that did not meet expectations, Smith concluded, ‘It’s a shame but he’ll never make a golfer – too much temper.’ Barnes could see beyond the inner rage and disagreed: ‘This kid will be one of the greatest in a few more years,’ he predicted. Rice added, ‘He isn’t just satisfied with a good shot. He wants it to be perfect – stone dead. But you’re correct about that temper, Alex. He’s a fighting cock – a hothead. If he can’t learn to control it, he’ll never play the kind of golf he’s capable of shooting.’