11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

The brilliant sequel to Bridge in the Menagerie, which won the hearts of bridge players 30 years ago. Improve your bridge the painless way with these hilarious and well-loved characters.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 190

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

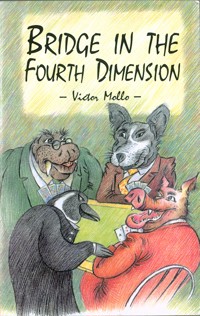

Bridge in the Fourth Dimension

Bridge in the Fourth Dimension

Further Adventures of the Hideous Hog

Victor Mollo

First published 1974

First Batsford edition 1996

Reprinted 2001

© Victor Mollo 1974

ISBN 0 7134 8004 1

eISBN 978-1-849942-11-9

Published as eBook in the United Kingdom in 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission from the copyright owner.

Published by Batsford, 1 Gower Street, London WC1E 6HD

An imprint of Pavilion Books Company Ltd

Contents

Acknowledgments

Author’s Preface

1. Bridge with the Unicorns

2. The Rabbit Takes Charge

3. Hog v Nemesis

4. Nemesis Keeps Her Lead

5. En Route for the Moon

6. Feats of Self-Destruction

7. A Greek Tragedy

8. A Top for Papa?

9. The Best Defence

10. An Ode to the Deuce

11. Papa Has the Last Word

12. Co-operative Finesses

13. The Art of Divination

14. The Latest in Safety Plays

15. Too Much Psychology

16. Seventh from the Left

17. Vive le Mort

18. A Spirited Defence

19. The Hog Picks Papa

20. Starring the Villains

21. Thirteen Wrong Cards

Acknowledgments

Most of the material in these pages has appeared in Bridge Magazine, where the Griffins and the Unicorns were born more than ten years ago. I am grateful to Eric Milnes, the Editor, for permission to reproduce.

I am indebted to the many friends of the Hideous Hog and the Rueful Rabbit who have asked me to write a sequel to Bridge in the Menagerie.

Finally, I am under a considerable obligation to the Hog himself. I have defamed his character and he could undoubtedly obtain damages for the wrong I have done him. With characteristic magnanimity, and for other still more compelling reasons, he has undertaken not to sue me. I hope that the rest of the cast will show similar indulgence.

Author’s Preface

As the lights go up in the Griffins Club and at the Unicorn, the points of the compass spring to life. With rich red blood coursing through their veins, North and South, East and West, don flesh and bones and race across the traditional diagram to a battlefield where men are men, seeking no mercy and showing none.

If bridge is the most fascinating of all games, it is because it is the least contrived and the most human, allowing each player full scope to show not only his cleverness and skill, but likewise his faults and frailties, and to enjoy his failures almost as much as his successes.

Can the player’s vivid dreams come true in a book? To bring this about must be every author’s purpose.

He sets out with a clear advantage. Leaving aside the prosaic deals which predominate at the card-table, he can conjure up coup after coup to dazzle and to bemuse as he passes on to the reader the secrets of bridge expertise.

There’s a price to pay. The triumphs and disasters of the written page bring neither elation nor despair, for they are abstract and no one is deeply stirred by the fate of lifeless puppets around a paper diagram. The human element is missing and that is the fourth dimension which makes bridge real and vibrant, raising it in stature above all other pastimes.

Of course it is intellectually satisfying to study the mechanics of a squeeze by South against West, but it doesn’t arouse the senses. How much more exciting to watch a duel between man and man, following the Hideous Hog as he strives to squeeze or smother his arch-enemy, Papa the Greek? Or to kibitz the Rueful Rabbit defeating a seemingly unbreakable contract by stumbling inadvertently on an inspired defence?

There are no fictitious characters in this book. The reader has met them all and will easily recognize their features beneath the allegorical guise.

He will soon identify Walter the Walrus, who counts rather than plays bridge and would sooner go down honourably with 30 points than bring home a dubious contract on flimsy values. He has often played with, and above all, listened to Karapet, the unluckiest player in the Western Hemisphere—and in the Eastern Hemisphere, too, of course. And who hasn’t suffered from the pedantries of the Secretary Bird, always prone to invoke the letter of the law, even if it brings about his own undoing?

Just as the dramatis personae are drawn from real life, so are the situations in which they find themselves. If some of them seem contrived, it is only because fact is stranger than fiction and bridge is often stranger than either.

‘Life is real, life is earnest’, and so is bridge. But need it ever be grim? And should it ever be dull? Of course not.

All humans are at times ridiculous, more often perhaps than they suspect. Hence the frequent touches of the burlesque in these pages. If the players were never comic, bridge itself would not be what it is—a magic mirror reflecting all the varied facets of human nature. Through this fourth dimensional mirror I invite the reader to follow the exploits of the Griffins and the Unicorns and to share fully their experiences. And now it only remains to switch on the lights.

1. Bridge with the Unicorns

‘The bane of duplicate,’ declared the Hideous Hog, ‘is its soul-destroying predictability. It’s morbid. It’s melancholy. And it makes for mediocrity. When a man knows that someone in the other room holds the same cards as he does, what incentive has he to make twice two come to five? Why should he bother when the other fellow may not even get the addition up to four?’

We were dining at the Unicorn, where we Griffins seek refuge during the first fortnight in August while the staff at our own club take their annual holiday.

Every year we see new faces—and old faces, renovated by time, and almost as good as new. We come up against new conventions, new hoary anecdotes, new clichés, and the Hog finds new victims to dazzle, to bemuse and to enrich him—though that, as he would say himself, is purely incidental.

The first of August was particularly hot with the thermometer rising to twenty-four degrees Centigrade. It was hotter still Fahrenheit. Having disposed of an iced Cantaloup, the Hog returned to one of his favourite subjects—the iniquities of duplicate.

‘At rubber bridge’, he was saying, ‘you win only by playing well. At duplicate it is enough not to play badly. The winners are simply those who chuck least. What a bleak and dreary way of life! Can you imagine Shakespeare or Michelangelo or Beethoven being satisfied with not making mistakes? Would Botticelli have given us the Divina Comedia just by not chucking?’

None of us seemed to know, but as H.H. was about to continue he was stopped short by a scathing snake-like noise. It came from the sole occupant of the next table, a man in his late fifties mounted on long, thin legs with a bird-like face and round bright eyes flashing from behind a pair of rimless glasses. Behind the ears of his small, globe-shaped head, projecting at right angles, were tufts of wild white hair. ‘Botticelli!’ he hissed. ‘Ignoramus!’

A strong current of mutual dislike quickly passed between the Hog and the long, thin man.

‘Who’s that Secretary Bird?’ asked H.H. scornfully, addressing Peregrine the Penguin, the Unicorn’s Senior Kibitzer, who was our host. Then, interrupting the Penguin smartly before he could begin, the Hog resumed his disquisition:

‘The true significance of bridge is that it faithfully mirrors life itself. The strong reap the reward of their strength. The weak are justly punished for their weakness and the winners rightly enjoy the esteem of their fellowmen,’ he inclined his head modestly, ‘which is as it should be. Not only is justice done, but it can be seen to be done.

‘But,’ declared the Hog with solemnity, looking like a pink, sleek edition of some ancient prophet, ‘duplicate sets at naught Nature’s moral code. Butcher a hundred contracts. Massacre a hundred partners. Commit felo de se. Misbid, misplay, misdeal. It will not make a pennyworth of difference. You can sin with impunity for you play for matchpoints and there is no distinction between right and wrong. And that is why I say that playing bridge not for money is immoral. It is a perversion, for Nature had not intended it that way.’

As we made our way to the card room, the Hog fired a final salvo:

‘Duplicate is all very well for the weak, unlucky players, who cannot expect much out of life anyway. They can take pride in being beaten by masters. The greater the master, the greater the honour. But who is going to look after the masters? Or do you really think that doing execution should be its own reward?

‘It’s high time’, concluded the Hog, glancing round for a table, ‘that someone spoke up for the strong against the weak. The underdogs have had it all their own way far too long.’

From a corner table, reverberating through the room, came a penetrating, resonant voice, proclaiming proudly: ‘I had sixteen.’ The voice belonged to a large ginger Walrus moustache behind which sat a fat man with pale blue watery eyes.

Looking round the room, we could see only one Griffin—Colin, a facetious young man, shaped rather like a corgi, who had only recently come down from Oxbridge. He was partnering the Walrus moustache, and one could tell at a glance that they did not love each other deeply, if at all.

We drifted towards their table and before long we heard the Walrus announce:

‘What could I do? I had only thirteen!’

Apparently, a cold grand slam had just been played in a part-score. The Walrus had opened 1 , which the Corgi had raised to 2 and there it stopped.

Their two hands were:

‘A bare thirteen,’ repeated the Walrus.

‘Well played Walter,’ said the Corgi when the thirteenth trick had been safely gathered, ‘a nice, safe contract and the hundred above the line is just as good as having honours. What’s more, with forty below, we need only another two grand slams like this one to give us game.’

With a grunt of pleasurable anticipation, the Hog seated himself by the Walrus. If there was going to be any sarcasm, bitterness and ill-feeling, that was definitely the table for him.

It was now Game All and 40 to North-South. West dealt and opened 1 . This was the brief, but telling auction.

West

North

East

South

C.C.

W.W.

1

Pass

2

2 NT

Dble

ALL PASS

West opened the 6.

East went up with the A and returned the 8 on which the Walrus played the 3. Still on play, East switched to the Q.

Suppressing a cry of anguish, the Walrus covered with his king and lost the trick to West’s ace. Four spades followed, declarer shedding a diamond honour and a club. Then came a heart and the Walrus, puffing indignantly, had to find three more discards. When East’s last heart, the five, settled on the table, the position was:

After trying each card in mid-air and muttering dark imprecations, the Walrus finally parted with the Q. It made no difference, of course, for West discarded after him and the defence was bound to win all thirteen tricks, inflicting a penalty of 2300.

‘I had twenty-one-and-a-half points!’ cried the Walrus indignantly, ‘twenty in top cards, one point for distribution and half a point for the ten of hearts. Twenty-one and ...’.

‘Isn’t something wrong?’ broke in the Corgi softly. ‘When you went down 1100 in 3 with me just now it was because you had 18 points. Now with only three more you go down an extra 1200. Can it be that the point count is not mathematically foolproof? And how few points must you have to escape catastrophe altogether?’

Walter the Walrus was too shattered to respond to sarcasm. In an incredulous voice he kept saying: ‘I had twenty-one. ...’

The Hog’s Debut

The Hog’s first partner at the Unicorn was Colin, the facetious Corgi-shaped young man. They soon made a game. The Walrus, sitting West, dealt and opened 1 . The Corgi doubled and East, a colourless Unicorn whose name even the Penguin couldn’t remember, passed.

This was the auction:

West

North

East

South

W.W.

Corgi

No Name

H.H.

1

Dble

Pass

2

Pass

2 NT

Pass

3

Pass

3 NT

Pass

4

Pass

4

Pass

5

Pass

6

Pass

6

Pass

7

Pass

Pass

Dble

ALL PASS

The Corgi admitted readily enough, when challenged by a Kibitzer, that his take-out double was shaded, to say the least, but having signed off three times he felt justified in accepting a pressing invitation.

‘And anyway,’ he added with a sly look at the Walrus, ‘reputations should be worth something, er ... his and hers, if you see what I mean.’

The Walrus, who had doubled in a voice of thunder, opened the K.

‘Thank you partner,’ said H.H. sweetly. The cordial note in his voice was a measure of the disgust inspired by the sight of dummy. It would have been poor tactics to encourage opponents by betraying signs of his disappointment. From every pore he exuded confidence and bonhomie.

But meanwhile, the problem remained. Was there any way of making thirteen tricks?

The hand could be played pretty well double dummy for his opening bid marked the Walrus with every missing honour. But was that going to be much help?

I saw Peregrine the Penguin shake his head. Two Unicorns, who were waiting to cut in, shrugged their shoulders and walked away dejectedly.

After winning the first trick with dummy’s ace, the Hog played a club and ruffed it in his hand with the queen. Then came a diamond to the table and another club ruffed high, followed by a second diamond and a third club ruff, this time with the ace of trumps.

The Hideous Hog now led the 2 and successfully finessed the 8, leaving this position:

After drawing trumps, the Hog led the 2, throwing on it his last diamond and retaining the A K 10. The Walrus was inexorably squeezed in the red suits. After much puffing he let go his 9 and ten seconds later it was all over.

B

‘I ...’ he began.

‘You had twelve points and two tens. I’ll say it for you,’ broke in Colin quickly.

The Secretary Bird Cuts In

I went across the room to make up another table and for an hour or so I lost track of the Hog, though I could still hear the Walrus announcing his point count in tones that were sometimes plaintive, sometimes angry, and often surprised.

Then the Secretary Bird joined the Hog’s table. Even at a distance I could feel the exchange of snarl and hiss as he took his seat.

When I cut out and went over to watch, I found H.H. sitting with:

As I sat down, he was saying: ‘Double.’ His partner, the Unicorn without a name, had opened 1 and the Secretary Bird (East) had called 1 NT. Walter the Walrus, sitting West, bid 2 and this was followed by two passes.

The Hog looked across at his partner, noted the awkward way in which he fumbled with his cards, and with a look of illconcealed dislike, applied the classical Rabbit treatment: 3 NT.

This was the sequence:

North

East

South

West

No Name

S.B.

H.H.

W.W.

1

1 NT

Dble

2

Pass

Pass

3 NT

I could read his thoughts. Yes, 4 or 5 might prove to be a better contract than 3 NT. But with so dim-witted a creature opposite how could one hope to find out? Besides, there was always the risk that unless one acted quickly the wrong man would play the hand.

The Walrus led the 3 and the nameless Unicorn put down dummy.

‘Bit of a misfit,’ murmured a kibitzer.

‘What a contract!’ observed another.

Even without the heart lead, the club suit looked pretty dead, for on the bidding, neither of dummy’s queens was likely to provide an entry and declarer would need two to set up the clubs and enjoy them.

The Hog played low from dummy to the opening heart lead and the Secretary Bird, winning with the knave, continued with the queen. H.H. threw on it his K, won the trick in dummy with the K and followed with the A on which he discarded from his hand the A. Next came the J. The Secretary Bird won it with the Q and returned another. He had clearly no intention of leading up to dummy’s queens.

The Hog proceeded to cash his clubs, which broke 4–2. On the last one the Secretary Bird threw the 10 suggesting that his pattern was 3–3–3–4. There was still a hope—that his spade holding was A J 10. Then he could be thrown in to lead a diamond away from the king. I peered into the other hands. This was the complete deal:

Having finished with the clubs, H.H. made a rather weird looking play of the low spade away from dummy’s queen. The Secretary Bird followed with the nine and the Hog, winning with the king, played back another spade. There was now no way of escape for S.B. for he only had the A J and the K J left.

‘Very lucky,’ he hissed. ‘I had every card that mattered and could not move.’

‘Ha!’ jeered the Hog.

‘Are you suggesting,’ asked S.B., his spectacles gleaming dangerously, ‘that I could have broken the contract?’

‘No. You couldn’t,’ replied H.H. ‘Anyone else, however, might have put up the J instead of the nine.’

The Secretary Bird tried to think of a crushing retort, but nothing suitably venomous came to him on the spur of the moment.

The Hog did not mind. He was engaged in his favourite pastime, adding up the score.

2. The Rabbit Takes Charge

‘Am I as bad as you think I am?’ The question was put to me by the Rueful Rabbit as he toyed with the heart of an artichoke over lunch at the Unicorn. Before I could form a suitably evasive reply, he went on:

‘They all think me crazy, you know, to play at high stakes with the Hideous Hog or even with Papa, for that matter. Don’t they realize that it’s perfectly couth to lose to champions. It’s taking a beating from palookas that’s so humiliating. Of course,’ went on the Rabbit, ‘it costs more to be thrashed by a first-class man. But one should not quibble, when it comes to paying for one’s pleasure, and, when all is said and done, there’s such a thing as self-respect. If not, the least one can do is to pretend there is. Think, too, of the thrill of putting it across the experts! You can’t get the better of them at golf or tennis or chess, no matter how much you pay. But it happens at bridge. Sometimes, the champions are too good or too clever and beat themselves. Sometimes you hold all the cards, which makes them very cross indeed. And sometimes, if you get into the swing of it, you can manage to be lucky. That’s the part I like best.

‘Of course,’ confided the Rabbit, sipping his Rosé d’Anjou, ‘it’s all a matter of degree. If I were clueless, like that poor Walrus or the Secretary Bird—Professor of something, isn’t he ?—I wouldn’t play at all. Looking ridiculous in public is undignified. But then, I am sure, that you don’t put me in that class?’

‘A most agreeable wine,’ I replied, ‘so light and refreshing. To follow, with your strawberries, I recommend a glass of the Corton ’64.’

Leaving the Rabbit to a bowl of Royal Sovereigns, I made hastily for the door. As I went through, I cannoned into Walter the Walrus.

‘Nice to have you Griffins here while your own club is being done up or something,’ he boomed. Then, dropping his voice to a confidential bellow, he went on: ‘I suppose the standard at the Griffins is pretty low. Even so, how can that chap you were lunching with, that Rabbit, manage to survive? Millionaire, I suppose ... game must cost him a fortune ... can’t tell one card from another ... can’t even sort them out ... amazing. Do you know what he did to me yesterday?’

‘Yes, I heard about it,’ I lied hopefully. But it didn’t help. He told me just the same. He started on another hand, but at last fortune smiled and the steward came in looking for someone who had booked a long-distance call to Tiverton, Tomsk or maybe it was Tegucigulpa. I forget now which it was, but I confessed at once that I was the caller and quickly darted round a corner, past the telephone booths and into the card-room. The Secretary Bird was the sole tenant. I tried to look inconspicuous, but I was spotted at once. A pair of long, thin wiry legs approached me. Looking up I could see two wild tufts of hair growing at right angles to the ears. Between them was a pair of bright round eyes sending out a brilliant dazzle from somewhere in outer space.

‘You are a student of human nature,’ was his opening gambit, ‘tell me, then, why is it that it happens at bridge? People who croak like frogs don’t insist on singing opera, at least not all the time. The lame do not take to sprinting. Yet men with anti-card sense developed to the highest pitch, play bridge every day. Take your Rabbit or our Walrus. Surely, each in turn must know that but for the other he would be the worst player in the world. Why, then, don’t they stick to marbles or noughts and crosses? Why bridge? I must tell you a hand....’

I was saved in the nick of time by an influx of players from the dining-room.

‘Remind me to tell you about the hand later,’ hissed the Secretary Bird as he cut an ace to find himself opposite the Hideous Hog. Neither made any attempt to hide his dislike of the other. The 2 and the 3 brought together Walter the Walrus and the Rueful Rabbit. They looked at each other with well-founded apprehension.