Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

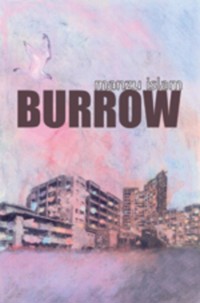

Tapan Ali falls in love with England and a student life of pot-smoking and philosophy. When the money to keep him runs out there seems no option but to return to Bangladesh until Adela, a fellow student, offers to marry him. But this marriage of convenience collapses and Tapan finds himself thrust into another England, the East London of Bangladeshi settlement and National Front violence. Now an 'illegal', Tapan becomes a deshi bhai, supported by a network of friends like Sundar Mia, who becomes his guide, anti-Nazi warrior Masuk Ali, wise Brother Josef K, and, sharing the centre of the novel, his lover, Nilufar Mia, a community activist who has broken with her family to live out her alternative destiny. Tapan has to become a mole, able to smell danger and feel his way through the dark passageways and safe houses where the Bangladeshi community has mapped its own secret city. He must evade the informers like Poltu Khan, the 'rat' who sells illegals to the Immigration. But being a mole has its costs, and Tapan cannot burrow forever, at some moment he must emerge into the light. But how can a mole fly? Manzu Islam has important things to say about immigration and race, but his instincts are always those of a storyteller. Using edgy realism, fantasy and humour to compulsively readable effect, he tells a warm and enduring tale of journeys and secrets, of love, family, memory, fear and betrayal. Syed Manzurul (Manzu) Islam was born in 1953 in a small northeastern town in East Pakistan (later Bangladesh). He has a doctorate and was Reader in English at the University of Gloucestershire, specialising in postcolonial literature and creative writing

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 539

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BURROW

MANZU ISLAM

For

Ines Aguirre

PROLOGUE

It all began with crocuses.

Each spring, for the last seven years, Tapan has been going to Hyde Park to see crocuses. He wanders at random, takes it slowly, stopping every so often for a closer look. He hunches over the clumps, brushes his eyes over the spread of colours. He compares the present blooms with those of previous years, and continues until he reaches the Serpentine.

He finds this ritual absurd because he is not into flowers and doesn’t care much for crocuses. Yet he comes here each year because crocuses petaled his earliest vision of England.

Long before he came to England, when he was growing up in Bangladesh, his grandfather gave him a book. He called him to the shade of the veranda in the afternoon. He was slumped on a canvas recliner, eyes half closed, puffing a hooka. Straightening his back slightly he took the book from his lap and handed it to Tapan. ‘My boy,’ he said. ‘ You can see England in this book. The most beautiful land on earth.’

He dutifully read the book to please his grandfather. The author, a Bangladeshi man of romantic temper, while giving vent to his passion for all things English, had composed a charming narrative of his brief stay in London. He forgot much of the book but the crocuses remained.

On his seventh year in England he goes to Hyde Park once more. It is a bright spring day. He gets off at Marble Arch tube station, walks along Bayswater Road, and enters the park through Victoria Gate. As usual he hasn’t set a precise course, but he knows that somehow he will reach the Serpentine.

He walks for a long time among the soft spring grasses, oblivious to his childhood vision of England blooming here in a mosaic of lilac, purple, yellow and white. He comes back, following the routes he has taken earlier, tries others that go straight between the trees, or diagonally across the grass that dips at a slight incline. He quickens his pace, almost breaks into a run to reach the next landmark, but still does not find his way to the Serpentine. He feels he is circling in a maze.

Exhausted, he sits leaning against the smooth trunk of a tall tree. Just to his right is a purple patch of crocuses. He turns his head to look at them, chooses the brightest one, and presses the tip of his finger against its spongy flesh. A wind slightly ruffles the grasses. He zips his jacket up and pulls his woolly cap down.

Recently he has been dreaming of something that he doesn’t quite remember. But this morning was different. A bang on his door woke him up and he caught the dream before it could flee to the other side of his memory.

He is sure that the season of his dream is autumn. He is by the sea. Trees are shedding their leaves. Suddenly a yellow leaf falls on his face. He does not flinch but picks the leaf up and feels its moisture in his hand. What connection does the leaf have with him? He doesn’t know – perhaps it’s not even important to know. All he knows is that the dream goes through him as though he is with an old friend in a familiar garden.

Nothing ruffles his dream: neither the roar of the wind nor the silence of the depths. But the yellow leaf whispering to the conch by the sea is different. Every time he hears the whispering leaf he is carried away as if by a lullaby across the seas. To an unknown land. No one notices his departure except his grandfather. He is happy, the tassel of his fez dangling in the wind. He smiles as he waves goodbye to Tapan. ‘See the crocuses for me, but take care not to touch them,’ he says. ‘It’ll please me, my boy, you seeing the crocuses for me.’

He arrives on a barren shore littered with the debris of lost time: muskets, gallows, steam engines, indigo, spices, torn muslin, and diamond encrusted crowns. Yet he expects his dream to bloom, as if on his arrival the bone dry land will receive long awaited rain. He is happy for himself and for his grandfather. But when it rains the whole day it leaves the conch full of water, right to its brim. So the whisper of the leaf turns back upon itself like the cry of Echo in the desolation of the forest.

He is ambling along the empty shore. Suddenly through the thicket of mist a horseman gallops towards him. He has a sword, unsheathed, in his armoured hand. The horseman’s face is covered by the visor of his jousting helmet, like a dark veil of death. The leaf, trembling somewhere between himself and the horseman, and unable to whisper to the conch, floats in the air. The horseman, with his spurred feet firmly in the stirrup and pulling the reigns tightly, gallops in to slice the leaf. His grandfather turns his back and walks away. Even the conch cannot mourn for the mutilation of the leaf. Hemmed in by the debris of lost time he lies flat on the sand. Then a sudden gust of wind brings the sliced leaf and drops it on his naked face. The horseman, with a pull on the reins, rides away, his job done.

Split in half, the leaf caresses his face, telling him the story it would have whispered to the conch if it hadn’t rained that day. To begin with, it tells him what he has always known, that he is indeed an intruder on the land of the horseman. And yet, hadn’t the horseman, a long time ago, set sail, with murderous conquest in his heart, for the land from where he came? Even in his dreams he is puzzled by this curious symmetry: he came here because the horseman went there. But unlike the horseman’s lumbering tracks through trails of blood, he came lightly, as if on the homing flight of a migratory bird.

Somehow, and always, he reaches a steeply sloping pathway that carries him headlong, as if he is shooting down a slide. Then he invariably comes up against the horseman. As expected, the horseman has already turned into the gatekeeper. He doesn’t see the expression on the gatekeeper’s face, nor does he hear him say a word. Rooted deep in his land, his bulk as stolid as the trunk of an oak tree, he is entirely given to the power of smell. When he attempts to sneak past, the gatekeeper smells him out and bars his way with his bulk. Seeing his desperate plight, his grandfather pleads for him, ‘Please, honourable custodian. Please, let my grandson enter your beautiful land. I’ve been a most loyal servant of your people. Look, I’ve brought you the duck curry. Remember how much you used to like it. Please.’ The gatekeeper not only ignores his grandfather but chases him away.

Exhausted by his repeated attempts to get through, he sits down in the shadow cast by the gatekeeper, whose girth matches his height.

He passes the time by waiting, expecting the gatekeeper to put on a face, until he hears the rustle of feet gliding through the mist. With swaying lanterns they are carrying a coffin towards the passage that leads to the gate at the end of the mist. On an impulse, he rushes towards them and asks, ‘Whose body are you carrying?’

They do not answer him, they are faceless and tongueless, as they approach the archway with the rhythmic sway of their lanterns. As though he has known of the approach of the body for sometime, and without a word being exchanged, the gatekeeper lets them pass.

Once more he hears the hooves, and when he looks back, he sees the horseman galloping towards him, the unsheathed sword in his hand. His grandfather is there too, observing the scene from behind the dunes, sobbing, but he does not come to claim the body: he is too ashamed of having an illegal immigrant as his grandson.

It is still bright in Hyde Park. A dog barks and comes to sniff at him and Tapan jumps up, shakes the dream out of himself. Frightened, the dog runs away as if it has seen a ghost.

Free at last, he walks through many more patches of crocuses, looking at their colours: how beautiful they look in this late afternoon, against the soft spring sun. He feels happy and finally, as he has done so many times before, he reaches the Serpentine.

CHAPTER 1

Nothing could be simpler. All Tapan had to do was to find two witnesses willing to tag along with them to the registry office. Once the ceremony was over, it was just a matter of waiting. The woman at the law centre told him, ‘If there is no complication you’ll be through the process in a year.’

He knew that the woman in round glasses did not believe his story. She had seen it all too often before to swallow any soppy shit about love. ‘Don’t drag love into this sordid affair,’ she seemed to be saying as she puckered her brow and looked beyond him. ‘I know you’re only interested in the marriage certificate. You want to legalise your stay in our country. Don’t you?’

Of course, there was no love. But what could be the complication? In fact it was Adela who suggested that they get married, pretend to be a happy couple until he got his residency. ‘Perhaps we can fall in love when you’re a full British citizen,’ Adela joked as they came out of the registry office.

Perhaps it was the marriage that poisoned the promise of love. Once they had concluded the transaction and become husband and wife on paper their fate was sealed. He needed to stay in England and she needed to betray England. In the following months, these things came between them, though there were no wild rows, hysterical scenes, or bitter accusations.

Even in their most tender moments, at the point of absolute surrender, when Adela gave him her green eyes without any reserve and he reciprocated, they became aware of their sordid transaction. If they went through with the act of love it was done with such abstraction, as if they were extracting pleasure from mechanical bodies. Worse still, like a whore and a gigolo.

Afterwards, they didn’t talk, carefully avoided each other. While Adela went for her long shower, he stayed staring at the television. Yet, there was a time when they felt at ease, if not happy, in each other’s company. He was Tapan Ali, a foreign student from Bangladesh, and she was Adela Richardson, a local English student. Both of them were final year students at a provincial English university. She studied Economics, he Philosophy.

When they first met, Tapan was part of a dopey bohemian circle on the campus, hovering around various international solidarity groups without any real conviction. He enjoyed women’s company but did not have a girlfriend. His real passion lay in consuming Western ideas: Spinoza’s geometric wisdom kept him trembling with joy the whole night, and if he needed love, Diotima’s discourse on Eros from Plato’s Symposium was more than enough for him. Besides, deep down he was still keeping time with his old Bengali clock. His upbringing hadn’t prepared him for free-floating erotic encounters. His instincts for finding a mate were switched off, because the people of his culture didn’t need them. They could always rely on an arranged marriage to take care of love.

Adela Richardson came from a well-to-do, middle-class family from the home counties. Her passion in life was betrayal: she wanted to betray her family, her class, her race, her nation and her history. The more she betrayed, the more she felt she had found herself.

When Adela led Tapan to the dance floor, she had no idea that she would end up marrying him. She had organised a late-night event to raise money for one of her many international solidarities. Was it for the Anti-Apartheid campaign, or for the Polisarios in the Sahara?

Under the dim light there was food and drink and throbbing music. Tapan didn’t take the floor like the others, who were dancing either in couples, or in groups of friends, or just moving solo. He was standing at the back, slightly awkward, drinking beer and smoking cigarettes. Adela, always the compassionate one, spotted him, and dragged him to the floor. It was a slow, deep, reggae number. Facing each other, but keeping a good distance between them, they danced. He didn’t know how to move and keep the beat. He wasn’t used to dancing. She knew the moves but looked inelegant, as if the smooth co-ordination demanded by the rooted pulse of the music was beyond her body. Suddenly she put her arms around him and pressed against him. He felt unnerved at the bodily contact and could hardly move his rigid limbs.

Many drinks later, his senses dull, when she took him to the floor for the second time, he was able to respond to her. She whispered in her ear. ‘You’re as brown as chocolate. Yummy – I like licking chocolate.’ He didn’t understand what she was saying but he offered his lips. And they kissed.

That night he ended up in her flat. Adela laughed. ‘You’re twenty-five and still a virgin. Am I corrupting you?’ She promised him that, like Elisa, she would be his sentimental educator. She kept her promise. The next morning he walked the rectangular squares of the campus, as if in a dream, thinking: was it love?

They never confronted this word but they became friends who from time to time slept together. He confided in her and she listened. He relied on her generosity, her empathy. She liked him the way she liked other foreigners. Dark faces. She didn’t ask for much; she was happy to give. The only thing she wanted was the recognition that she was different from the rest of her kind.

No, she had a soft spot for him. She liked the way he looked at her as if through the colour of her skin, through the blond roots of her dark hair, and through the green of her eyes. Yes, through the bodily surface to the beautiful self inside. She felt safe around him, liked the way he walked, his long thin body, his crazy hair, and his silly smile. Above all, with him around, she felt so different from her origins, and felt it so effortlessly that she felt permanently changed. It made her happy. But she didn’t call it love.

In the spring term of his final year a telegram came from Bangladesh. His grandfather was dead. He didn’t know the complexities of his grandfather’s finances. Apparently he had left a large debt. He could well believe that because it had cost a lot to support his study in England for the last five years. The first two years went into polishing his English and completing his A levels at Hackney College in London. The last three at this provincial university. Whatever the truth about his grandfather’s finances, the money stopped coming from Bangladesh. He could borrow from friends, work on the sly. That way he could somehow see the year through. But at the end of it, that is, by the summer of ’77, he would have to return to Bangladesh. He had no other option.

He thought none of this at the time he received the telegram. He locked himself in his room, opened his grandfather’s letters. In the main they were formal letters: how was his health? How was his accountancy study coming along? Had he got used to potatoes and kippers? Oh yes, in his first letter he asked whether he had been to Hyde Park to see the crocuses. In the last few letters he mentioned that he was looking for a wife for Tapan. As soon as he returned home after his studies he would be married. A beautiful wife and a good family.

During his five years in England he had grown distant from his grandfather. Even come to despise him. And there was the lie that he was studying accountancy. Often he would imagine his grandfather saying in a stern voice: ‘Accounts, my boy. Not only is it a sure big earner but much more. Forget about wasting your time on this no-good philosophy business. Otherwise, you’ll go nutty thinking Either/Or, and doing Nichtung. If you want to harness the power of Western mind, get hold of their double-entry bookkeeping. You’ll find there the secret art of empire.’ In those moments Tapan would laugh at the old fool and savour his sweet revenge. Perhaps, like Adela, he was also driven by his need to betray.

Now he wasn’t laughing. He felt guilty for lying to him and sad. He sobbed over the letters. His grandfather was all he had.

As usual it was Adela who came to comfort him, took him for a walk by the lake. That night there was so much intensity when they rubbed their skin against each other, he thought it must be love.

He was resigned to the inevitable. He would have to go back to Bangladesh. He could do nothing to alter this, but Adela said there was a way: he could marry a British citizen, and this would sort out his residency problem without much difficulty. But who would marry him? ‘Why,’ said Adela. ‘I’ll marry you. No strings attached. You’d have no obligation towards me.’

‘Marriage is serious business, Adela,’ he said. ‘We shouldn’t take it so lightly.’

‘I don’t believe in marriage, Tapan. I’d never get married for real. It’s only to fuck the system, isn’t it? You get your problem sorted without any cost to either of us. Nothing could be simpler.’

He didn’t argue with her for he wanted to stay in England. He had nobody and nothing in Bangladesh to go back to. Here he had his friends. Besides, the kind of life he wanted to live was only possible in England. He wanted economic independence, anonymity and no responsibility for anybody or anything.

He got married to Adela and, their studies finished, they moved to North London in the summer of ’77.

‘Since we’ve got to pretend, let’s pretend that it’s real,’ said Adela as she rolled the walls yellow. She wanted to give her new home in North London a bright look for both of them.

‘Of course we’ve to pretend that it’s real. Otherwise, we’ll be found out by the Immigration,’ said Tapan as he painted the ceiling white from the middle rung of the ladder. He wouldn’t have minded the old way the interior looked but he was happy to go along with Adela. Besides, a newly decorated home, with its carefully considered colour scheme harmoniously blending with the arrangement of furniture and paintings, would make a good impression. It would signal their commitment – the effusion of love that so spontaneously ought to be theirs as a newly married couple – and their desperate need to carve out a protective zone from the chaos outside. Especially for their little ones to come. It would be foolish to take any chances with the ever vigilant immigration officials.

Adela didn’t respond; she got on with the task with the same unfaltering rhythm as before: sliding the roller almost vertically up the wall, bringing it down, then going horizontal, adding a few short, sharp jabs, and finishing it off with a long arc of a flourish. When she bent down to gather more paint from the tray on the floor, some strands of her dark hair with blond roots strayed onto her face.

Out of the corner of his eye, under the harsh light of the shadeless bulb, Tapan saw a woman straining her back at the most ancient of labours – the task of building her nest. She wasn’t pretending: it was a labour of absolute conviction. How could she do this without the promise of love? All they had between them was a pretence, a deception coolly calculated so that he would get to stay in England. Seeing Adela straighten her back, he took his eyes back to his brush strokes on the ceiling.

Resuming her painting Adela said, ‘If we believe that it’s real, we don’t have to pretend.’

‘You know it’s pretence, Adela,’ he said. ‘Remember, you don’t believe in marriage.’

‘Don’t pretend that you don’t understand. Of course, I didn’t mean the bloody ritual. And the legal shit. You can be so silly sometimes, Tapan.’

‘But I like you, I respect you. And I’ve always admired you. That’s no pretence, Adela. But it’s as real as it gets with me.’

‘I know that, Tapan. But I mean the feelings that make people do stupid things like getting married. Can we believe that feeling is real with us?’

When Tapan climbed down the ladder, Adela continued to paint. He put his arms around her and planted a kiss on the back of her head. She turned around to face him with the roller still in her hand. It didn’t matter that the paint was dripping on the floor because they saw something new in each other’s eyes. Although they didn’t want to spoil the moment by giving this feeling a name – not now, not ever – they liked what they saw. Almost simultaneously they gave their lips to each other the way they had their eyes.

With her good economics degree Adela could have gone for a well-paid job in the City. Instead, she joined the economic regeneration unit of the local council. While Adela went out to work, Tapan stayed at home. Until he got clearance from the Home Office he did not have the right to work.

Each morning he waited for the dog from next door to bark and for the postman to curse. He collected the post as soon as it was pushed through the door. As yet there had been no news from the Home Office. He was slightly anxious but not unduly concerned. He got on with tidying up the house, went to the local library to read the newspaper, did some shopping in the afternoon. By the time Adela returned home in the early evening he had done the cooking. While Adela told him about her day at the office over a glass of wine, he set the table. Over dinner Adela continued with her anecdotes, telling him of the intrigues between her colleagues, of her new assignments, of the horrible man from the housing department leering at her and, always, of the terrible traffic. Afterwards, they did the washing up together, watched the TV, read books and went to bed. If one of them was in the mood the other obliged and they made love. Some evenings Kofi turned up after dinner and they smoked dope and listened to music. Most weekends they met up with Eva and Kishor to have dinner together, gossip long into the night, and smoke dope. If they went to a demo – CND or Anti-Apartheid – Kofi and Danzel joined them. Occasionally they went to see a film or a play. As time went by they seemed to have forgotten the ignoble origin of their marriage, felt contented the way most couples do in the routine of their domestic life.

Then one morning the letter from the Home Office arrived: they were to go for interviews together and separately.

The interview together went well, the questionings were unintrusive and polite; they went over their old story of suddenly falling in love and of their desperate desire never to be separated. The case officer seemed impressed by Adela’s job, by Tapan’s education, and of their home so near to his favourite football team. He even chatted with Tapan about Arsenal’s new signings and form this season and wished them good luck. But the separate interviews were very different. Both of them were called at the same time: Tapan was led to a cubicle halfway down the corridor, and Adela further along.

‘Would you be so kind as to tell me,’ the officer asked Tapan, with a straight face, ‘the middle names of your parents-in-law.’

Tapan stayed quiet, scratched his head, and bit his lips.

‘Right now I can’t remember.’

‘I see. By any chance do you know their denomination?’

‘No.’

‘Your wife, Mrs…’

‘Mrs Adela Ali.’

‘How old are Mrs Adela Ali’s nephews?’ The officer asked with the same straight face as before. ‘Sorry, forgive my mistake. They’re your nephews too. How old are they?’

‘I don’t remember.’

‘Do you know the name of the school your wife went to?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Isn’t the country you come from…’ the officer hesitated, ‘One of the poorest on earth?’

‘Yes.’

‘Don’t get me wrong, Mr Ali. I understand your situation,’ the officer said, in a voice of concern. ‘Life would be so much easier for you here. Wouldn’t it?’

‘Maybe. But I didn’t marry Adela for that.’

‘Good. Why did you marry then?’

He wanted to go over the old story of falling in love and their dreams of life together but remained silent as the officer lifted his brows and waited for the answer. Lying didn’t come easily to Tapan at the best of times. Now he seemed incapable of even the most inept of lies. When the officer cleared his throat with a muffled cough and looked at his watch, Tapan said, ‘Because we like each other.’ He paused, looked rather abstractedly at the blue globe on the table, and added, ‘Adela is a good woman.’

‘Of course. Of course,’ said the officer. ‘I understand.’

When Tapan returned to the waiting room, Adela wasn’t there. He sat down, glanced at the glum, tense faces of people sitting in rows, and waiting their turns to be slaughtered in the cubicles. Mostly brown and black faces like his. He wondered what tales they were rehearsing in their minds. Would they be candid about their appalling miseries and calamities and beg to be let in? Or, would they invent some fancy tales of love?

When the man next to him asked for the time, Tapan pointed to the large clock on the wall and got up. He shuffled across the room and stood against the large glass window. From there he could see only the massive flank of another identical building and another identical window in which stood a figure, perhaps looking out as vacantly and as lost as himself. He wanted a cigarette desperately. Then Adela walked in looking withdrawn and they hurried out of the building. They said nothing to each other on their way home in the tube, or during the walk from the station.

Now, while he put the kettle on, she went for a shower. Adela took showers as if crises could be washed away in torrents of water. The tea was lukewarm by the time she returned to the kitchen in her bath robe. She picked up her cup and sat on a stool slightly behind him and at an angle, so that he couldn’t see her face. Taking a sip she said, ‘You don’t want to know what they asked me?’

‘What’s the point, Adela. It couldn’t have been good.’

‘No. It wasn’t good. But they can’t deport you as long as we stay married. And feel it for real.’

‘How can we feel it for real, Adela? We got into this shit so I could fool the buggers to let me stay in this country. You could do a good turn for a wretch like me and betray your family into the bargain. That’s all there was to it.’

For a long while Adela stayed quiet, sipped tea and swung one of her legs like a pendulum. At last she said, ‘I can’t deny what you’ve just said. But when you put things like that it sounds so horrible.’

‘These are facts, Adela,’ he said. ‘We’ve got to face up to them.’

‘But if we feel it for real, we can put it right. Can’t we?’

‘We can play-act, masquerade, Adela.’ His voice was raised and trembling. ‘We can cheat the whole goddamn world with our mimicry. But we can’t invent real feeling.’

‘If I’d become Muslim, would it have been more real?’

‘What a daft thing to say. Where on earth did you get that idea?’

‘It’s what the immigration officer asked me.’ Adela said this so quietly that Tapan didn’t hear her clearly.

‘What?’

‘The immigration officer asked me if I became a Muslim when we got married.’

‘Oh I see. What did you say?’

‘What could I say? You’ve never asked me to become a Muslim.’

‘Let’s get one thing clear, Adela,’ he said. ‘Even if I were marrying for real, I wouldn’t ask my wife to become a Muslim. You don’t know anything about me.’

Adela got up and went to bed; he stayed up staring at the TV. No, they didn’t know much about each other. If they’d been truly in love they would have talked silly things about the schools they’d gone to, bored each other with sugary dribbles over their little nephews and nieces, and perhaps even learnt the middle names of their parents. And, of course, she might have understood why it wasn’t important for him to have her convert to Islam.

They tried to get on with life as best as possible, but things were becoming more difficult. They had several visits from the Home Office: officers going through their rooms, wardrobe, sleeping arrangements to pick up the slightest sign of a bogus marriage. Each visit left them unsettled, added one more unbearable strain to their relationship, so that whatever attachment or companionship there had been between them began to fade. More and more, they felt soiled by their sordid contract, exchanged without the slightest moral consideration, solely for the profit they stood to gain.

No matter how hard Adela tried to imagine her marriage signature as a pure altruistic gift, with no expectation of return, she felt used. Although Tapan had much less reason to feel used, he couldn’t let go of the nagging feeling that he was merely an unfortunate object of her pity and charity. Besides, he was the means through which she wanted to complete her betrayal. It seemed they were doomed.

And nearly a year after their marriage, the Home Office still had not concluded its investigation. Recently, there had been strange movements at odd hours in the house opposite. They didn’t know for sure what was really going on but both of them, separately, and without having talked about it, felt that perhaps a surveillance team had moved in.

Then the Home Office got in touch with Adela’s parents.

CHAPTER 2

Adela was preparing to leave for the office when the telephone rang. Still half-asleep in bed, Tapan opened his eyes and saw her picking up the receiver. Her lips quivered in a strange mingling of surprise, joy and terror. He heard her say, ‘Mum.’ She asked the caller to wait a minute, put the receiver back on the cradle, went downstairs and closed the door behind her.

It was the first intrusion of family into their lives. Although Adela had never spoken of it explicitly, knowing what he knew, Tapan sensed that this was bad news. It was there in the way she said ‘Mum’ into the cold, plastic mouth of the receiver. But why this secrecy? What was it Adela didn’t want him to hear? Her mother’s hysterical ravings about her dreadful deed with a wretched Paki? Perhaps she didn’t want him to witness her defensive, almost childlike responses to her mother’s assaults. Or was she gloating over her triumph, her betrayal of everything that her parents stood for? Yes, yes, I share my bed with a dirty, devious scrounger of a Paki.

He came down when she’d finished. Her face was red and there were tears in her eyes. ‘What’s happened, Adela?’ he asked.

She turned her face away from him, wiped her tears and said, ‘You don’t want to know.’ Then she gathered her handbag and left for work.

He didn’t feel like staying home that day. Luckily it was Kofi’s day off, and about midday he set off for Kofi’s place, twenty minutes’ walk, in Stamford Hill. It was early summer – the summer of ’78 – and the sun was out after the persistent rain of the last few days. Kofi was pleased to see him but said, ‘What’s wrong with you, Brother? You don’t look right to me.’

‘Nothing special really. Just things are getting a bit heavy, you know.’

‘That’s badness, Brother,’ Kofi said. ‘Come in. Let’s get us sorted.’

It was when he was doing his A levels at Hackney College that Tapan had met Kofi, who’d come from Ghana to join his parents. There he’d also met Danzel, whose parents came the Windrush way from the West Indies, though he was Hackney-born and never set foot out of London. They were good friends and when they donned their brown duffel coats and round metallic glasses and walked down Kingsland High Street, they appeared to be members of an exclusive club, but unlike the other two, Tapan wasn’t a British citizen.

‘I’m making the old stew, Brother,’ Kofi said. ‘Fancy number one hot?’

‘Yeah.’

Tapan loved Kofi’s number one hot, which was twice as hot as his hot curry, and a perfect accompaniment to a spliff.

‘Roll a joint, Brother,’ Kofi now said, ‘while I make us a number one.’

Kofi’s bedsit looked dark even on the brightest day. He never opened his curtains and he wasn’t keen on bright lights either. A dim light in the corner was all there was in his room, creating a twilight zone in which the hues were so faint that they looked like scrubbed watercolours. When Tapan once asked Kofi about this dimness and he said: ‘Brother, it’s to catch time.’

Kofi’s number one was as hot and good as ever. While they ate, Kofi put some music on, very low. It was Gregory Isaacs – the cool-ruler of the universe – taming the tempest of turbulent Kingston. After the meal, on their second joint, Kofi asked him, ‘So, Brother, what’s bothering you?’

‘Well,’ said Tapan, ‘this bloody immigration thing is getting on my nerves. I should’ve gone back to Bangladesh.’

‘Easy, Brother. Easy,’ Kofi said. ‘They want to see how much shit you can take. Don’t let them get the better of you. Play it cool like Gandhi.’

‘But it’s messing me up, Kofi. It’s even introducing bad feelings between me and Adela. I should’ve gone back to Bangladesh.’

‘There’s time, Brother, time,’ Kofi said. ‘You can go back when you get your citizenship. Don’t let the fuckers beat you.’ After a long puff on the spliff, he added, ‘And don’t you mess around with Adela. She’s a good woman.’

Later Kofi suggested they go out for a walk, as they used to do when they were green in London. Kofi loved architecture. Often they went to central London to see the grand buildings along the river. Kofi walked around them enchanted, now coming close to see the details of carvings, now standing right back for the long perspective, and always taking note of the arches, columns, cornices and the traceries on the windows.

Tapan didn’t care much about buildings, he was more interested in the way Kofi loved them, responded to them. One day Kofi had been looking and loving the buildings in his usual way, when suddenly his mood had altered.

‘Look at the fine works, Brother. Beautiful,’ he said. ‘But what do you see?’

‘They’re very impressive looking.’

‘Look, Brother, look. Carefully. What d’you really, really see?’

‘I don’t understand what you’re getting at, Kofi.’

‘Don’t they poke your eyes, Brother, with the muscles of empire?’

‘What?’

‘Yeah, Brother. You’re looking at the body-builders of empire. Real heavy stuff. Bad business.’

‘But they are beautiful. Aren’t they, Kofi?’

‘Yeah, Brother. Beautiful. I love them. But deep down they’re real wickedness.’

The clouds, gathering when they went out, broke as they reached the bus stop, so instead of going to see the buildings by the river, they went to Centerprise to play a game of chess.

It was early evening, and Centerprise was full of chess players, book readers and local revolutionaries of all shades of colours and doctrines, and a good number of casual interlopers brought in, like them, by the sudden rain. There were no empty seats left. So what to do? Perhaps they could call on Eva and Kishor.

Before that Tapan phoned Adela.

‘How are you, Adela? We must talk, you know.’

‘Not now, Tapan,’ she said. ‘I’ve just got back from work and have to go out again. I’m in a hurry.’

‘When will you be back?’ he asked. ‘Shall I cook for you?’

‘I don’t know when I’ll be back. No need to cook. And don’t wait up for me.’

Hoods up on their duffel coats, they went out in the rain again. At the bus stop they bumped into Danzel, who was on his way home from work. ‘How you doing, my main man?’ he said to Tapan, who just shrugged his shoulders. ‘Is it that bad?’ said Danzel. ‘Don’t let the Babylon system get you down, Brother. Stay cool.’

When the bus came Danzel said he would join them later at Eva’s and Kishor’s. At Finsbury Park, Kofi told Tapan to go ahead. He had to score some dope, from a dealer nearby.

‘We’re going to have a mighty session tonight. One of them master-blaster, Brother,’ Kofi said with a grin.

Eva and Kishor were Tapan’s university friends. Kishor, a high-caste Hindu, had come to England from Kenya. Eva, a mestiza political refugee, had fled the death squads in Colombia.

Looking at Tapan’s gloomy face, Eva was about to say something witty to cheer him up, but seeing his eyes, locked as if in a crypt, she swallowed her words, and looked over his head at the blue ceramic bells dangling from the ceiling.

‘Let’s see what we can do about that grim face of yours,’ said Kishor. ‘How about a joint, my Bangladeshi Brother?’

Tapan nodded his head slightly.

As Kishor heated the resin, letting loose the oily aroma of Afghan Black into the unvented air of the room, he said: ‘Beware! Beware! The Mujahideen are coming.’

While Kishor rolled the joint, Eva went to make tea in the kitchen. Handing the joint to Tapan, Kishor put on a tape: it was LKJ chanting in ragamuffin rage: Inglan is a bitch over the top of a heavy bass-line riff and depth-charge drum beats. It made Tapan ease up a bit and he smiled as he took the tea from Eva. She wanted to ask about Adela, but sensing that something was wrong, and not wishing to spoil the moment, she didn’t.

‘You’re lucky, Compañero,’ Eva said. ‘Kishor has cooked beef today.’

Kishor laughed out raucously, as he always did, to draw attention to his beef-eating ways. As usual, Eva couldn’t resist commenting cynically, ‘Attention. Imperialism is shaking. Our Hindu comrade is eating beef.’

Undaunted, Kishor half closed his eyes, put his chin up, and held the pose as if he didn’t intend to drop it until he got his due recognition. Tapan began studying the dangling ceramic bells and Eva got up to change the music.

Feeling stranded, Kishor blurted out the punchline: ‘Beef!’ Eva tossed her head; she’d had enough of this stupid joke.

No one knew how it started but it had become an in-joke among the members of the dopey circle at university. One of them just had to mention Beef and the rest would give themselves belly-aches, laughing.

Now Tapan swallowed his usual chuckle with a long drag on the joint. Eva put on Joe Arrano’s salsa Colombiana. She resumed her seat opposite Tapan and began to mouth the lyrics and move her head to the rhythm. Then she looked Tapan straight in the eyes and asked, ‘Is Adela joining us tonight?’

‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘But Kofi and Danzel are coming.’

Eva sprang to her feet saying that there weren’t enough tomatoes for a salad for four, sent Kishor to the kitchen to cook an extra pot of rice and went out to buy some tomatoes from the open-all-hours Oriental store down the road.

Tapan rang to see if Adela was back home, but she wasn’t. Perhaps it was for the best because he didn’t know what to say to her.

Tapan joined Kishor in the kitchen. ‘Relationship botheration, eh?’ Kishor said. ‘Join the camp, mate.’

Eva’s and Kishor’s relationship was regularly difficult, but that had to do with the complexities between lovers. Before Tapan could point out that his difficulties with Adela weren’t anything like theirs, Kishor was telling him that the political situation in Eva’s country had changed.

‘She wants to go back as soon as possible.’

‘Are you going with her, then?’

‘Shit, Man. No. I admit England could be a bitch sometimes, but we know her.’

‘So, you don’t love her any more?’

‘Of course, I love her,’ said Kishor. ‘But England is home – isn’t it? I just can’t leave. Whatever the difficulties, I’ve to fight it out here.’

‘So love is not enough.’

While Kishor searched his mind to say something that would make sense, they heard the front door open. As usual, the grocer had short-changed Eva, but she came back laughing.

‘He’s real sweet. He calls me Madam Latina,’ she said. ‘Funny. He told me I was practically one of his people.’

‘He’s a bloody con artist. Don’t you be taken in by him,’ said Kishor.

Eva ignored him and began to lay the tomatoes on the chopping board.

‘What people does he mean?’ Tapan asked.

‘Not Colon’s Indios,’ she said. ‘But real Indians from India proper.’

Kishor laughed with such childish innocence that Eva mellowed towards him, giving him the bright brown bubbles of her eyes. Seizing the moment, Kishor slipped in his silly Beef joke. Eva wasn’t annoyed this time; she leaned back her head, laughing. ‘Tonto,’ she said. Now they were back again: a couple in love.

When Kofi and Danzel arrived, they all sat down to eat. Kishor was happy because everyone complimented him on his excellent beef curry. Afterwards, Eva proposed that they should go to the pub down the road. Friday was jazz night. No one was particularly keen to go out but they didn’t want to disappoint Eva, so, after a joint, they went to the pub. Before they left Tapan called Adela once more. She wasn’t home.

In the pub, they sat in an alcove that protected them from the buzz of activities around the musicians, who were already in full flow. Danzel bought a round of Guinness for everyone, except Kofi, who never drank any alcohol. He had coke.

After the second round, Eva tried to cajole them to jive to a jazz number with a frantic swing. Having failed, she took to the floor alone. Danzel, pointing to the musicians, sucked his teeth and said, ‘Rass. Me jus’ kyaan believe it. White them playing jazz.’

Nobody paid him much attention, except Kishor, who gave him a reproachful look. Surprisingly, Danzel didn’t accuse him of being a ‘bloodclaat coconut’ as he usually did when he was in his ghetto talk mode, and instead turned thoughtful and recited fragments of Langston Hughes: ‘Jazz – tom tom being in the negro soul…the tom tom of the revolt against…white world.’

Kofi said, ‘Really!’ and took to the floor. While Eva messed around, keeping time with her snapping fingers, he shimmied, rooted to the spot. He moved a few notches down from the tempo of the music, creating a virtual rhythm of his own, as though his own body was an instrument, providing a counterpoint.

Back in Eva’s and Kishor’s flat, Tapan phoned Adela again. It was past midnight and she still wasn’t home. Kishor was rolling his Afghan Black, Kofi and Danzel their home-grown grass. Eva put on Joao Gilberto – so cool and bohemian – playing Bossa Nova.

Then between Burning Spear rooting deep into the earth and Dexter Gordon saxing the midnight into an abstract melancholy, they smoked on, all except Eva. She never smoked dope – it was anti-revolutionary escapism – though she would happily roll joints for the group.

Suddenly Danzel asked, ‘Who wants to leave this Babylon and go back home?’

Kofi said he was serious this time, he would be back home by the end of the year. Danzel said he would go back with Kofi – they had already worked out a good plan. Tapan wanted to stay in England and Kishor wouldn’t go anywhere else. Eva said, ‘You lot are junkies for England, Compañeros. None of you would ever go back.’

‘We’re immigrants, Comrade,’ said Kishor in a tone of crude sarcasm. ‘We love England.’

Now Eva was really cross; she sat quiet, studying the blue ceramic bells and when Kishor put a record of flamenco guitar on the player, she went to bed. The rest smoked on, letting the flamenco guitar creep into them almost imperceptibly, and then, when they least expected it, rush back to thrust its matador’s sword right through their hearts. Then there was Billy Holiday singing ‘April in Paris’ in a voice so sad and sensuous that it made them laugh and cry all at once. Finally, they settled for Bismilla Khan playing shehnai with Allarakha on the tabla.

From corner to corner the room was full of smoke; suddenly Bismilla Khan was blowing so fast and furious, dropping notes like a heavy downpour of rain, that poor Allarakha, despite the dexterity of his fingers, was finding it hard to keep pace.

They would have let Bismilla Khan go on for the whole night if Eva hadn’t got up to complain.

Tapan tried one last time to call Adela. She still wasn’t home, and since he wasn’t keen to go back to the empty house, Kofi invited him to stay at his place.

As Kofi took off his shirt to sleep, Tapan caught sight of his amulet and remarked: ‘Surely, Kofi, you can’t take that old mumbojumbo about the amulet seriously?’

He was recalling what Kofi had told him about the amulet the first time he’d noticed it – that when he was leaving for England he’d gone to see the griot – known as the machine of ancient memories in his village – and he’d given Kofi the amulet and told him that the ancestors had harnessed and sealed the whistle of birds in its wooden body. If the passion of birds was stirred in the body of the wearer – as it must when the desire for flight and escape reached their limits – the amulet’s power would be released like the wind of harmattan. When that happened the wearer was pulled beyond the force of gravity. But this, the griot had cautioned Kofi, was a very dangerous thing to do.

Enigmatic as ever the memory machine wouldn’t confirm this, but Kofi was sure that many of the ancestors had released the secrets of the amulets, especially while limbo dancing in the triangular Belsens of the Atlantic, and whistled their way into the air. And then back home.

Kofi fingered the amulet and said, ‘Easy, Brother, easy. Most of the times I don’t. For example, when I look at my watch, put on the light or take a train, I don’t.’

‘And isn’t that the world we live in?’

‘Certainly, Brother. That’s why I don’t believe in the amulet most of the time.’

‘When do you believe in it then?’

‘To be frank with you, I don’t believe in it at all. But sometimes I feel it.’

‘I don’t get it, Kofi. What do you mean?’

‘Listen, Brother, if I can put words to the feeling, then it wouldn’t be feeling any more. Right?’

‘I still can’t get my head around it, Kofi.’

‘You will, Brother. When you get the feeling yourself.’

Tapan stayed silent for a while, thinking, but when he wanted to ask Kofi further questions, his friend had already fallen asleep. Finally, alone in the room without shadows, he thought about what he had been avoiding the whole day: perhaps he should move out of Adela’s home before their relationship became more complicated, before real bitterness set in.

CHAPTER 3

Tapan knew that terrible things were happening in East London, but what could he do about them?

He didn’t belong to a political group, nor was he part of a community. He attended CND marches and Anti-Apartheid rallies in the broad avenues of central London, and the festive Rock against Racism concerts that took place in well-kept parks. They were, he would admit, more like outings to him than arenas of political involvement. Besides, though he was a Paki like them and suffered his share of Paki-bashing, he’d had nothing to do with the Bangladeshis of the East End: they were almost as alien to him as the Cypriots of Green Lane.

But on his way home from Kofi’s place, a young woman with cropped hair had pursued him until he bought a copy of the Morning Star. On the bus he flicked through the paper, made a mental note of the article on the second page, and came back to it when the bus halted in a traffic jam. Apart from telling of the general harassment of the Bangladeshi community, it catalogued a series of violent assaults and murders. Recently, there had been more ominous developments: the National Front had laid siege to the heart of the community in Brick Lane. During the week this siege simmered and on Sundays it exploded into battles. The National Front would gather at the corner of Brick Lane, selling their newspaper Bulldog, and the Bangladeshi community, supported by anti-racist groups, would try to prevent them. Below the article there was a little ad urging people to come down to Brick Lane the following Sunday.

As the bus finally arrived in Manor House, Tapan folded the paper in the long pocket of his duffel coat, and got off. It was a damp and overcast Saturday. He was slightly nervous as he unlocked the front door and walked in. At first he thought Adela wasn’t back home yet. It was silent and the curtains were drawn. His half-empty cup of tea still lay on the glass-top table where he had left it.

It was only when he was halfway up the stairs that he heard the shower. He paused, and then continued up, heading for the bathroom. He would slip in quietly – as he had often done – and greet her through the pale blue shower curtain, ask her about yesterday’s phone call, about last night. At the point of turning the handle on the door, its cold aluminium tingled the tips of his fingers. He was invading the privacy of a woman having her shower. He had no right to do so; it would be an act of violation.

He wasn’t sure whether Adela had heard him. If she had, she didn’t give him any sign; the shower went on with the same torrent as before. He came down, put the kettle on, and waited in front of the television. She didn’t come down in her bathrobe, pouring on him the perfume of her fresh skin mingled with eucalyptus, as she usually did after a shower. Instead, she went to the bedroom, slipped into the green dungarees that made her look pale and misshapen, and then came down. He wondered why she had put them on. She hadn’t worn them for ages, ever since he’d told her how terrible she looked in them. He turned the TV off and asked her if she wanted a tea. She didn’t.

He didn’t ask her about the phone call or where she’d been last night. Nor did she ask him anything, though she told him that the strange activities in the house opposite were to do with squatters. The police had been there only an hour ago to secure the place for the owner – apparently an Asian, big in real estate. She went upstairs and read a book, made several phone calls, while he watched football on the TV downstairs, sprawled on the sofa and slept. In the late afternoon she came down – as quiet and unobtrusive as before – to make tea and toast. He pretended not to have noticed her. After she went up the stairs again, he went to the kitchen to cook. Usually they went shopping on Saturdays, but since they hadn’t bothered, there wasn’t much to cook. He rustled up a curry with the leftover vegetables and waited for her to come down, which she did, in the late evening.

She gave him a can of lager and opened one herself. Facing a print of Cézanne’s Portrait of the Artist’s Wife on the wall, they ate in silence, passing things to each other with exaggerated politeness. Both of them glanced at the print several times, but neither was sure whether it was simply to bear the silence between them, or to see something in it. If the latter was the case, neither had the slightest idea what they had seen.

After dinner, they did the washing up together. Back in the living room, each on their separate sofas, they sat as if they were strangers in a darkened theatre, absorbed in their separate ways by the unfolding tragedy on the screen. At last Adela said, ‘Now that there’s no pretence any more, we must find a way of bearing it.’

‘Do you want me to move out?’

‘Well. You can stay until your papers come through,’ she said. ‘I imagine that should be pretty soon.’

He didn’t say anything; he just meekly squashed his eyes to convey something – what, he wasn’t sure. Agreement? Gratitude? Resignation? Or, just sadness? She went up to the bedroom, he made his bed on the sofa. It was the first time they’d slept separately in the same house since they got married.

He had a restless night, his mind spinning. What could he do or say that would make it up to Adela? Should he pretend that he had just realised how much he loved her, and confess it with such a display of sincerity that she would shed all her misgivings about him, making both of them sob until they wiped each other’s tears, carried away, as if the most beautiful thing had just happened to them? How low could he get? At least she deserved some honesty from him. But what could he do? Should he just call it quits and go back to Bangladesh?

If his parents had been alive, it would have been natural for him to go back; perhaps he would never have come to England in the first place. Strange that he hadn’t thought about his parents for years. He had no memory of his mother. She had died giving birth to him in her mother’s hut at the edge of the great swamp. Sometimes he dreamed of his mother, of the folds of her sari, really. Now he sees himself in the hut in which he was born, lying beside his mother.

As always the old cobra emerges from the dense undergrowth that surrounds the hut. He is not scared of the cobra; it is not known to have harmed anyone. Thunder and lightning wake him and he hears the cobra as it passes, slithering, as though the last thing it wants is to disturb anyone’s sleep, past the mud hut with its corrugated roof, across the plain dotted with tall trees, towards the great swamp. For reasons known only to itself, the old cobra always keeps to a precise time, between the waning of the moon and the cry of the jackal. Soon after hearing the hiss of the cobra and the pattering of the rain, he falls asleep.

Only later, when an intense desire to see the cobra makes him grope under the pillow, through the folds of his mother’s sari, is he scared. No one has ever seen the cobra. All that is known of it is the hiss of its passing in the rain. When there is no rain, and the night sky is full of stars, you become aware of it simply by opening your ears to the inaudible murmurs beyond the clamour of the world.

It is not really a dream about his mother, but about the folds of her sari, and only of that brief moment when he looked for the cobra. When he was child, he had loved to fold himself in the sari his grandmother told him had been his mother’s. In those moments he felt protected. Even now, at rare moments, he wishes he still had the innocence of feeling that way.

Although his father lived until Tapan was eight years old, he didn’t see much of him. He lived with his maternal grandmother in the hut at the edge of the great swamp. His father visited him occasionally and brought him books with pictures in them. His father and his paternal grandfather didn’t see eye to eye. Indeed, their relationship had so broken down that he didn’t know he had a grandfather until his father’s death. Although he’d heard that his father’s death was to do with his political activities, he never knew exactly how he died. He neither saw his dead body nor attended his funeral. He never dreamed about his father, but often fantasised that he was alive, and that he comes face to face with him in the street of a strange city. Although his father does not recognise him, walks past him, and disappears into the crowd, he feels happy because he knows that his father is still alive.

Tapan didn’t know when he had fallen asleep, but he was woken up by violent retching sounds coming from upstairs. Adela was vomiting in the bathroom. He went up and stood outside the door and asked if she needed help. She said he shouldn’t worry; it was nothing serious really, only a mild case of food poisoning. No – he shouldn’t call a doctor. She went to bed and he made tea and toast and took them up to her. She thanked him and said that she would be going out a bit later, but didn’t say where.

When she went out, he looked at the little ad in The Morning Star again. He wasn’t sure what made up his mind, but he was on the bus – on his way to East London.

Brick Lane was crowded though most of the people in it had nothing to do with either of the sides of the barricade. They were mainly punters on their way to or returning from the Sunday market. It was where Brick Lane joined Bethnal Green Road that the battle line was drawn: from the Bethnal Green Road side the National Front threatened to break into Brick Lane amidst the flutter of Union Jacks, and from the Brick Lane side a small group of Bangladeshi youths, supported by anti-racist groups, tried to block them. In between them there was a large number of police officers.