Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

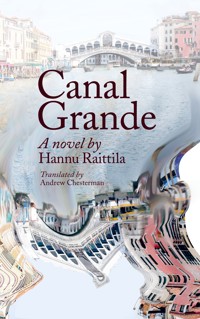

English translation of Canal Grande, a novel by the contemporary Finnish writer Hannu Raittila. The novel won the Finlandia Prize celebrating the best Finnish novel of the year when it was published in 2001. A team of Finnish experts is sent on a UNESCO mission to save Venice from sinking. A rich social comedy unfolds as northern cool meets Mediterranean carnival: two very different manifestations of modern European culture. But beneath the satire, a more serious moral critique develops, as darker sides of human behaviour are gradually revealed...The final pages are an emotional shock, as we realize how much the Finnish experts have not realized. The novel switches between the viewpoints of several contrasting voices, from different members of the team of experts. The main voice is that of Marrasjärvi, the team's resouceful and ever-rational hydro-engineer, a specialist in freezing, who will solve any technical problem and even save a donkey from drowning. Other team members are Saraspää, an ageing cultural hedonist who keeps a very personal diary, and Heikkilä, an academic historian who is fluent in Latin and ready to lecture on anything at any time.The last voice is that of Tuuli, the team's bilingual secretary, who lives in a different world and saves more than a donkey. Underpinning the often farcical culture clash there run deeper themes exploring the gap between rhetoric and reality, the limits of rationality, what might make a good life, and human tragedy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 458

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

WINTER

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Chapter XXII

Chapter XXIII

Chapter XXIV

Chapter XXV

Chapter XXVI

Chapter XXVII

Chapter XXVIII

Chapter XXIX

Chapter XXX

Chapter XXXI

SPRING

WINTER

I

The fog continued into a third week. Diving down out of bright sunshine the plane had glided into a bank of low cloud just above the ground only a few hundred metres before the runway. I didn’t see the airport or the surrounding area. I had noted from the map that between the sea and the mountains there was a broad plain. Presumably the airfield had been built on this low-lying land, where only floods might hinder the operation of the flights.

Snell gestured towards the fog and said we needed to take a taxi. The Councillor for Cultural Affairs is a fat woman. She was breathing heavily after having to walk down the escalator. I had pressed the button, but nothing happened. I went with Heikkilä in the direction Snell had indicated, looking for a car. Saraspää shouted through the fog that we shouldn’t go far because the sea was over there.

Snell spoke to some official and kept repeating something. The word was vaporetto, but it didn’t make any sense to me then. She didn’t seem to understand what the uniformed man was explaining. Saraspää went up to them and asked if Snell was unaware that the vaporettos and taxis didn’t operate on the lagoon in this sort of weather. We would have to get into town by car. I no longer understood what they were talking about. Seagulls screamed somewhere close by, and there was a smell of fish.

We took a bus through the fog. The trip seemed to take ages, but I suppose it was because we could see nothing of the landscape we were driving through. We came to some place where there were rows of cars. This became clear as we walked forward. Out of the fog emerged one car-bonnet after another. They were lined up like the vehicles of a motorized troop unit in the collection area before an attack. I thought we were in a supermarket car park, but there was no sign of any shoppers pushing trolleys. We would have heard the clatter if they were being pushed around. On the other hand, I didn’t know the local opening times. Did they have a siesta?

I was a bit surprised at the number of the cars. I had been told that there was no car traffic at all in the city. And no supermarkets either, apparently, although the whole settlement had been founded by traders. The smell of the sea was persistent, and the fog stuck to the surface of my poplin coat in tiny droplets. Beneath our feet the asphalt changed to paving-stones. Nothing else of Venice was visible.

We walked along by the wall of a building. The sound of cars faded. There was only the splashing of water on the left, and Heikkilä warned us not to stray from the side of the building. He said the pavements were narrow, even in this main street. He reminded us that the traffic routes here are canals. We were walking along one of the biggest ones right then. A train approached and stopped with a hiss. There was a hasty, confused announcement, after which the electric engine whined and clacked in the fog like a large animal. Snell was badly out of breath. We went up some steps. Heikkilä explained that we were on a bridge, we were now crossing the Canal Grande.

On the other side of the canal Snell and Saraspää began wondering again whether to take a taxi or a vaporetto. Heikkilä said the word meant a water bus. I realized that a taxi, too, was actually a boat. Snell examined a brochure, evidently a local timetable, and said vaporetto number one stopped near the hotel where we had rooms reserved.

Saraspää said vaporettos only do one departure in three. No one asked why. A big diesel engine suddenly accelerated right next to us and there was a whiff of naphtha. The revolutions slowed and the engine noise became more distant, as if a heavily laden truck had released the clutch and set off laboriously in low gear. We heard the water churn and then sharp waves slapped the stonework almost at our feet.

Without a glance at timetables or maps Saraspää added that vaporetto number one stopped on the other side of the canal and we would have to walk half a kilometre through the alleyways to the Rialto Bridge and then all the way back along the opposite bank of the Canal Grande. The alleys were labyrinthine, criss-crossed by little canals and with deceptive twists and turns, so that a pedestrian would very soon be walking in the opposite direction without even realizing it. He said that in such a fog, and with all our luggage, we should not take a single step into the sidestreets.

In the water taxi Heikkilä gave a running commentary on the famous palaces and other buildings we were passing. Heikkilä is an adjunct professor at Helsinki University and has a senior researcher’s grant from the Finnish Academy. He was brought into the team as an expert in cultural history. He is never at a loss for words. In the plane he had already been telling us about his research on medieval and Renaissance city states.

I would really like to have seen all the palaces Heikkilä described. When checking through the project’s documents I had of course seen pictures of houses rising straight out of the water, with jetties where normal buildings have steps. I had also seen the building plans for these houses and I knew they were on foundations made of larch piles.

All of a sudden the driver snapped at Heikkilä. Embarrassed, he stopped his commentary on the history of the invisible buildings along the canal. Saraspää began to laugh. The boat slowed and stopped at a jetty built of marble slabs.

We disembarked, Snell after considerable hesitation. Being a large woman, she took some time to pluck up courage to step onto the jetty, which was half a metre lower than the rocking deck of the boat. I held out my hand and Snell leaned on it so heavily that we both almost fell into the canal, dragged down by the councillor’s weight.

January 8.

Arrived in Venice. The days before were nothing but rushing about, a nervous flight from thoughts and memories. I get so muddled I just can’t cope with simple travel preparations I have been through thousands of times. I arrange my toilet bag again and again, with the intention of ensuring an adequate supply of medicaments for the trip. In the middle of the packing, a glass pill bottle falls to the floor and breaks. I go into town to get another one. The editorial secretary of the Suomen Kuvalehti periodical suffers the consequences of all this when he stops me quite innocently on Alexander Street and says he has heard about my trip, that I am a member of an “international team of experts”.

The poor fellow then asks me for a cultural piece on the upcoming carnival, and there in the middle of the street he gets a right earful of my views on Venice and its carnivals. Blinking in confusion, the young journalist stammers something about Finland’s participation in the preservation of Europe’s cultural heritage. With venom in my voice, I ask what heritage he is talking about.

“It’s the loot of a pack of gangsters,” I snap, when he wonders how the artistic treasures of Venice should be defined. The wretched man is startled at my outburst, but still tries to splutter something about Italy and the Renaissance. I totally lose my temper and bawl at him – Were the Medicis or the Borgias anything else than the mafiosi of their time, just the same as the guys who these days establish theatres, art galleries and cultural magazines in Russia? And the robbers of Venice have always been the greatest thugs of all! Heads begin to turn in the crowd. I leave in some haste; curtain…

Once in the plane, an obligatory whisky highball. Half way through the flight I hear with relief the captain’s announcement: Venice is hidden in thick fog. Blessed nebbia! I am saved. Two or three g&t’s downed in quick succession mean that I arrive at the Aeroporto Marco Polo in a distinctly mellow mood.

A delightful intermezzo on the way to the hotel: our councillor, of considerable size and eternally short of breath – the esteemed chair of our “team of experts” – tries to get the airport staff to order a water taxi to the centre. In this total pea-souper the water traffic on the lagoon has obviously been cancelled. We have to take a bus via Mestre to the Piazzale Roma, from where we walk, hugging the walls, to the railway station square. Here at last we pick up a water taxi, driven by a real Venetian character.

One of our experts, Heikkilä, a university professor of history, gives us a voluble introduction to the important buildings along the Canal Grande, and their history. Because of the fog, we obviously see no glimpse of these palaces. He blathers on and on like a tourist guide, until the driver has had enough and growls: “Non è Canal Grande!” The taxi had left Ferrovia along a side canal so as to cut out the upper bend of the Canal Grande…

Otherwise, the prof and Marrasjärvi, the engineer who has been hired as an expert in construction technology, are good fellows. I am especially taken by Marrasjärvi, who seems to be a quintessential Finnish man. Heikkilä and I have a couple of amaros in a bar near the hotel. He recalls, with a laugh, the tourist trip on the Canal Grande and its embarrassing finale. It turns out that he doesn’t know Italian. But he does speak Latin! Speaking slowly and pronouncing carefully, he makes himself understood, to the great delight of the listening Venetians.

January 11.

The fog continues. I have never, not even in this city, seen such fog. I walk along familiar alleys and canal banks in a state of total confusion. There, out of the foggy mist emerges a familiar bridge railing, and over there a miniature carving on a palace’s door frame or a baroque knocker twisted into fantastic forms, all enveloped in swirling tongues of mist, now vanishing, now reappearing, so that after a moment you wonder whether what you see is of this world or emerges from the recesses of your own mind. And yet this city is the creation of merchants with no illusions, who have valued only tangible materials and goods. When I go back to the hotel, I leave behind me a lazily swirling passage in the mist, which gradually closes into an opaque wall of fog.

II

Two weeks passed and I still hadn’t seen a single one of the Canal Grande palaces we were supposed to be saving. Of the whole city of Venice I had only seen the paving stones beneath my feet, crumbling brick walls along which we had to feel our way in the fog, and heavy, decorated hardwood doors. Sounds of water surrounded us everywhere. In the damp air was the smell of the sea, and ships’ sirens hooted on the canals and on the lagoon, which I knew surrounded the city, as I had checked out the geography of the area on my maps.

The office premises we had been promised had not been made available. We had seen them: three rooms in a building on the Canal Grande quite near the hotel. The name of the building was the Palazzo Inverno and it was supposed to be city property. Heikkilä said the name meant winter palace. It didn’t look much like a palace. We would be given the rooms at the earliest opportunity. To heat the place some kind of oil-burning stove had been brought. It had been lit shortly before we arrived. There was still a good deal of damp in the rooms. The stone wall sweated like an ice-cold beer bottle brought into the warm. The place smelt as if it had been left unheated for ages.

The street building office was apparently still waiting for some documents without which our contact person, a talkative and overly friendly official, could not hand over the premises. I wondered how Venice got to have a street building office, seeing as there were no streets. Heikkilä grew impatient: relying only on his Latin, he tries to make sense of the official’s rapid Italian. He apologized if he had given an inaccurate translation of the Italian terminology of municipal administration.

Anyway, as a bureaucrat myself, surely I should know that administrative titles often didn’t correspond to the duties which came to be performed in their names. What did the Helsinki procurator fiscal actually do, for instance? I denied being a bureaucrat. Heikkilä said there was nothing wrong with bureaucracy, contrary to what people were always saying. He had studied the birth of bureaucracy, which was one of the basic conditions for the development of modern society, as were democracy, the rule of law and free markets. I said I was no kind of bureaucrat. He insisted that all civil servants were bureaucrats. I told him I was not a civil servant.

He argued that we were all currently working for the Ministry of Education and hence in the service of the state. I informed him that I worked for a private engineering firm from which the ministry purchased consultancy services. Heikkilä was astonished. He asked how much I earned. I said I had a monthly salary which was pretty average in my field for an engineer with similar work experience.

Heikkilä knew that private sector salaries were high. He thought I would be expensive for the taxpayers. I told him that the state had to pay more than just my salary. My employer charged a fee for the service, which covered additional costs, the firm’s fixed and running expenses and a profit margin. The total invoice was much bigger than my salary. But this undoubtedly still worked out cheaper for the taxpayer than if the Ministry of Education were to establish its own permanent staff of engineers for all its development aid projects.

Heikkilä asked if I thought I was in some developing country. Was I supposed to know where I was, in this fog? Didn’t I know I was in Italy, in the city of Venice, he asked in surprise. Italy is an industrialized country and Mestre, right next to Venice, is a centre for the heavy petrochemical industry. Heikkilä said I should go and see the hellish industrial zones in Mestre or the huge Chioggia docks. There, among the containers destined for all over the world, I could consider whether I had come to a developing country.

What could I know about the docks and factories of Venice? For two weeks I had seen nothing beyond the length of my arm. I was nevertheless under the impression that UNESCO was some kind of development organization, and as for the costs incurred due to my stay in Venice, I wanted to keep them as low as possible. I would have liked to be already working on the task which the Ministry of Education had, in its wisdom, brought me to Venice to accomplish. Heikkilä laughed.

I was a typical northerner – an engineer and a man. We were now in the world south of the Alps, in the Apollonian culture of the Mediterranean. I would have to get used to a new concept of time. I said I had been getting used to this for two weeks now. In the world north of the Alps, in a Finnish engineering company, quite a bit could be done in two weeks, such as a hundred and sixty metres of a new water tunnel from Lake Päijänne to the Silvola reservoir near Helsinki. Heikkilä asked if a hundred and sixty metres was a lot. I told him it was a world record.

Still laughing, he explained the chain of commissions that had brought me to Italy: the Finnish Ministry of Education had agreed to send a delegation of specialists to the city, but our actual employer was UNESCO, which was far from being just a development organization. It was also concerned with the preservation of the world’s cultural heritage, and that’s why we were in Venice, in the midst of this heritage.

When I was studying, they kept banging on about the importance of the division of labour. Accordingly, I intended to carry out my own work as well as I could, without interfering in the activities of the other team members, and I wasn’t going to start wondering who I was ultimately working for. I received a regular salary from my firm and took care of the projects assigned to me. Heikkilä was delighted.

In his view, it would be hard to find a more typical representative of technoculture and compartmentalized expert power than myself. Using the participatory observation method, he was going to study how I behaved in the Latin culture, and with colleagues from the humanities, too. I told him he could begin his participatory observation right here and now.

I said I was going to begin the basic measurements required by the project myself, because in two weeks the Italians had not been able to deliver the information I had requested. Heikkilä could come with me as interpreter and guide because he knew the city. He regretted that it was fourteenth-century Venice that he knew best. I said the project would proceed with the resources available. I told him to come along and we set off into the fog.

We walked along the alleys keeping close to the walls. Judging by the sounds, every now and then we crossed a small side canal. In the city the sounds of water never faded completely. Sometimes the alleys were so narrow that with outstretched arms you could run your fingers along the walls on both sides. Occasionally it seemed that the street went inside a building for a moment. Out of the fog emerged a black text daubed with spray paint: LEGA NORD. There the wall ended. Over the black writing a cross had been drawn, and next to it SERENISSIMA. Heikkilä asked if I thought I knew where we were. I said we were at the Campo Sant’Angelo.

He disappeared into the fog for a moment, then reappeared wondering how I had known our position. I showed him the map where the square was marked. How had I managed to walk through all those alleys so unerringly, in thick fog, to precisely the square I wanted? We were not there yet, I said. I wanted to get to St Mark’s Square, did he happen to know which way it was? Heikkilä led me to the corner of a building. There was a sign in the shape of a yellow arrow and the text PER SAN MARCO.

“The square’s over there.”

He added that the direction indicated by the arrow would not help us for long, when we made our way back into the twisting narrow alleys wreathed in mist. I said I’d been walking along the main routes from the hotel. I had proceeded with a map and a compass, counting the street corners and canals. In this way I had arrived at the city’s huge car park, the Piazzale Roma, the railway station, the Rialto and Acc-ademia bridges and also St Mark’s. Heikkilä assured me he admired my map-reading skills but still failed to understand how these heroic feats could help us now. At any rate, he had not been counting the street corners and canals and had not noticed me doing so either. I showed him my GPS unit. He thought it was a mobile phone. I told him the next generation of phones would indeed incorporate GPS technology, but up to now satellite navigators were separate devices. He was astonished. Had we traversed the Venetian alleyways guided by a man-made heavenly body? I showed him the navigator. It records journey co-ordinates in its memory and transforms the parameters on the screen into route guides. You can easily retrace a route by following the localizer on the screen. If you stray outside the prescribed range, the device beeps and gives a correction course to the next turning point on the route.

When we got to St Mark’s I asked the direction of the bell tower. For a minute or two Heikkilä examined the corner of the building we had bumped into, thought with his head tilted back, and then gestured into the fog: the Campanile was about a hundred metres in that direction. On that corner the square makes a turn. At right angles to the main St Mark’s Square there is the smaller Piazzetta Square. It opens onto the Riva degli Schiavoni, the Promenade of the Slavs, which runs along the side of the canal. Heikkilä pointed, his arm straight as a general’s. The plane of his outstretched palm stirred the mist, which concealed within it all the sights he had described. Had I asked him for some kind of guided tour? And why did the Slavs have their own promenade in Venice?

He explained that by Slavs they meant the peoples along the Dalmatian coast on the other side of the Adriatic: Croatians and the inhabitants of present-day Slovenia. They had traded with the Venetians since ancient times. Contacts had been broken only temporarily – for fifty years, when Tito set up the artificial federal state of Yugoslavia. I said I hadn’t asked for a lecture on the history of the Adriatic nations, either, I just wanted to know the location of the Campanile tower. He pointed into the fog again. He was amused that I didn’t see this from my gadget. Unfortunately the same principle applies to satellite navigators as to other new technical devices: they only know what has been fed into them, and I hadn’t programmed the direction from the corner of the square to the bell tower.

Heikkilä waved his hand again, like a dictator in a benevolent mood. From the top of the Campanile tower, more than a hundred metres high, on a bright day you could see the whole city and the lagoon around it, the nearby islands and the endless reedbeds beyond them. His gestures made wisps of mist swirl around his outstretched hand: to the south was the Lido and the other sandbanks which separated Venice from the Adriatic Sea. To the north lay the Veneto plains, and behind them in good weather you could see the Alps. Heikkilä said he’d be glad to climb the tower with me on a clear day, but what was the point of going to the city’s best viewpoint now, when one didn’t even have an uninterrupted view of one’s own shoes.

I was not interested in views. The tower was the fixed point I had selected from the map, allowing me to locate the other points on the square. Heikkilä responded with enthusiasm. Which buildings was I interested in, the Palazzo Ducale? No, I said. As far as I knew, the city had not been administered from the Doge’s Palace for years. I had seen on the map that on one side of the square was the Procuratie Nuove and on the other side the Procuratie Vecchio. I had found out from the dictionary that the latter meant the old administrative building and the former the new one. I assumed that the city’s various governing bodies had their premises here. Heikkilä was miffed that I hadn’t asked him.

We had to walk back the same way to the hotel, from where we proceeded along another route I had recorded to the Rialto Bridge. At the street corners and on pillars emerging from the fog the same text kept reappearing, scrawled in ink or paint: serenissima. Next to it there was often some kind of coat of arms, painted with a template, with a golden lion on a red background. I asked Heikkilä if he knew what this serenissima was. He explained that it meant “noblest of all”, i.e. the Duke of Venice, the Doge. He added that the expression La Serenissima meant the Republic of Venice.

We groped our way across the Ponte di Rialto. From the bridge we followed the bank of a canal, and counting the street corners arrived at a small square by the water. According to Heikkilä, the Palazzo Loredan should be here, where most of the city’s municipal offices were. He asked why we had come here. I said I needed a water-level gauge and some flow meters. He began wondering what they were in Latin.

January 14.

Our gallant engineer, Marrasjärvi, seems to be the one whose nerves are most frayed by our enforced idleness. The prof does his best to entertain him with more or less risqué Venetian anecdotes from centuries past. Today we were shown the “office premises” we had been assigned: Marrasjärvi inspected the structural condition of the building and the electrical equipment and telephone cables with extreme suspicion.

The premises were presented to us by a city official from the Municipale. Elegantly attired in two-tone but sober shoes and a stylish suit, with an umbrella against the nebbia, the gentleman regretted the absence of certain documents which were still needed before the premises could be handed over for our use.

It was clear as day that the issue in question was something quite different. A lack of papers has never prevented Italians, let alone Venetians, from getting on with practical arrangements.

January 18.

Our culture councillor is excruciating company. As head of department in the Ministry of Education, Snell is the self-appointed leader of our group. I really have to labour as madame’s adjutant and escorting officer. One day when we met she made some personal comments about me, saying she had exerted all her authority in order to get me included in the team: “Saraspää is a unique Finnish cosmopolitan, a connoisseur of European culture. On no account can he be overlooked as our country embarks on such a significant pan-European cutural project.”

Madame also took it upon herself to speak of the city, and said among other things that Venice in its lagoon is like a jewel on a cushion of blue velvet. The situation was saved by the engineer, who made the reasonable comment that at the moment the city is entirely hidden in fog. I hope the nebbia goes on for ever. I don’t wish to see anything of the whole junkyard. My thoughts have begun to revolve obsessively around matters of the heart. And besides, I feel I shall shortly be succumbing to my old vice.

January 23.

Stormy scene today in the Palazzo Loredan. Marrasjärvi had got into the city’s administrative headquarters escorted by Heikkilä. They had appeared out of the fog at the door of the office like the Finnish cavalry on the bank of the Rhine in the Thirty Years’ War. Oblivious of the gestures and frantic shouts of the porters, the engineer had coolly walked straight into the interior of the Municipale like the Carolean sergeant Simuna Antinpoika at the French king’s court.

“Keep your bloody hands away from your pistol,” Marrasjärvi had shouted when one of the porters had groped for his white gun belt, which belonged to his operetta uniform. The two men had barged into a committee meeting of some kind and the prof had explained their errand, in Latin: they needed to procure the equipment needed by the engineer for the measurement of the current flow in the canals.

Staff from the technical department had rapidly brought the necessary apparatus while the ingratiating deputy mayor kept the two fearsome northerners company with an espresso.

I must say I enjoy our engineer’s methods in much the same way as I liked the way the bootlegger Vikki Kivioja sympathized with socialism.1

1Translator’s note: there are several cultural allusions in these paragraphs. The Finnish cavalry referred to were the famous Hakkapeliitat, so named because of their battle cry “Hakkaa päälle!” – ‘Cut them down!’ Simuna Antinpoika is the hero of the story The Carolean Box on the Ear by Kyösti Wilkuna (d. 1922), about a Finnish soldier who visits the 17 TH century French court in Versailles, where he is treated as a comic barbarian until he shows his strength. Vikki Kivioja is a character in Väinö Linna’s trilogy Under the North Star (1959–1962), a Finnish literary classic.

III

We set off with the equipment towards the Accademia Bridge. Heikkilä had a shoulder bag in which we packed the flow meters and the water-level gauges I had made from some 4-inch planks. In my own rucksack I had a hammer and nails, a battery-operated hand drill, a saw, cable ties and a couple of coils of rope. We had calibrated the current meters by pulling them at a constant speed in the bath and counting the revolutions of the propellers. I also carried a long pole in order to measure the depth of the canal and thus calculate the area of the cross-section. The passers-by must have wondered somewhat, seeing a man emerge from the fog with a ten-metre stake in his hand.

Heikkilä assured me that at no point would the Canal Grande be deeper than five metres. In fact it was much shallower. At the bridge the canal was about forty metres wide. We measured the depth in five places and I multiplied the average depth by the width. I then sawed the pole into lengths which I fixed to the level gauge and the flow meter. I attached these to the bridge so that the zero point at the centre of the scale coincided with the water surface. Having zeroed the revolution meter, I lowered the propeller into the water so it would be turned by the current, about one and a half metres below the surface on the outer bend of the channel, fairly close to the bank. I didn’t dare leave the stake and gauge in the centre, where the gondolas and freight barges could have collided with it.

Heikkilä stood at the edge to check, and shouted when my red zero mark on the plank was flush with the water surface. He recalled his high school classes in maths and statistical graphics. The frustrated teacher had sent the boys out to toboggan on their geometry books. That’s how Heikkilä had become a humanist scholar. I explained that by using the channel cross-section, the streamflow and the water-level values you can calculate the rating curve, and then draw up a table from which the stream discharge can be read directly from the water-level observations.

We fetched some more stakes and went off with the GPS to the Ponte di Rialto and the Ponte Ferrovia. On both bridges we fixed the same kind of apparatus we had installed at the Accademia. Now we could check the Canal Grande flow at the mouth of the canal, half way along, and at the neck. When we got back to the Rialto there was a wind blowing. It quickly strengthened to quite a gale. From the compass on my smartwatch I saw it was blowing from the southeast.

The fog rapidly started to shift and was soon torn to shreds. It looked like when an aircraft dives out of a cloud into bright sunshine. Between the patches of mist I began to see the city where I had been wandering about for a couple of weeks totally blind. Every now and then the whole canal became visible, and the sturdy bridge above it. I had walked over the bridge and stopped to stand on it too, but its form was only familiar from the pictures in the pocket tourist guide. On both sides of the canal buildings rose straight out of the water. They had entrances supported by pillars, and arched windows. The sun came out and the wind flapped the striped awnings on the red-brick palace that was revealed at the corner of the bridge. The awnings said HOTEL RIALTO RESTAURANT.

People flocked out of the buildings and palaces. There were kiosks on the bridge, and the sellers came to the railing to shout and wave. I asked Heikkilä what they were shouting, what had got into everybody. Had someone fallen into the canal? He thought they were yelling that the fog had dispersed. Wasn’t that obvious to anyone with eyes, even without yelling? We went to take the rucksacks back to the hotel. Heikkilä wanted to go via some church. It was a famous Renaissance cathedral, which he wanted to see now that the fog had evaporated at last. He explained that the church also concerned us to some extent. Was it a specially protected building? He said it had been named also in our honour, we who had come to the city to help save it. Its name was San Salvatore.

From the hotel we walked to the Accademia to check that the meters were still there. Heikkilä wanted to go via St Mark’s. I was happy to see some of the sights myself, too, now that they were visible at last. He babbled on and on. It was as if a plug had been removed. Names of streets, canals and palaces came pouring out, dates, families, mercenary chiefs, grand merchants and famous writers and other artists who had visited Venice to work or die. I didn’t really listen but looked at the buildings. They were the reason for my presence in the city. Along the stone foundations of all the buildings ran a damp calcified line. Below it the paint and plaster were flaking off onto the paving stones. I knew the cause of this damage. I even knew the Italian term for it: acqua alta – high water. At St Mark’s Square Heikkilä announced that to celebrate the dispersal of the fog we should go to Harry’s Bar.

There were others in the bar, also celebrating the dispersal of the fog. The place was nearly full. Harry himself shouted something and set down on the bar a couple of glasses containing a brown, sweet drink. Heikkilä listened to Harry’s shouts with a hand cupped behind his ear, and said the round was on the house. This was before the bar had got completely full. I tossed it back, and then had to drink several times from the empty glass when everyone else made toasts and speeches, raising their glasses and sipping.

I went to sit at a table, but Heikkilä made me get up again. He explained that table service was many times more expensive than ordering from the bar. I thought we had funds enough to cover sitting at a table. I was tired. Heikkilä claimed sitting at a table was especially expensive at Harry’s. I wasn’t worried about that, since so far I hadn’t had to pay for anything, but I followed him back to the bar.

I asked him what kind of Italian spirits corresponded to our Koskenkorva vodka. He reckoned it would be grappa. I asked him to order some. He told me to order it myself. I raised two fingers and said “grappa”. Harry was amused. He poured something into small glasses, not quite a clear liquid, slightly yellowish. Harry asked something. I waved my hand at him. I tried to offer some money, but he seemed not to notice. The grappa tasted like moonshine.

Heikkilä related the story of how the cunning Venetian merchants had stolen the earthly remains of Mark the apostle from Alexandria. As he was speaking, his foot slipped off the rail which ran below the counter just above the floor. Without pausing he bent down and tied his shoelace as if he had planned the whole manoeuvre. The Italians at the bar had been listening to him and asked something. He spoke to them in Latin and some other language, which he said was Hebrew. In Finnish, he explained to me that in the Accademia there was a work by Tintoretto, “The Abduction of the Body of St Mark from Alexandria”, but its documentary value was questionable.

The bones of St Mark had been taken in a sack to the harbour, where the Venetians had a ship ready to sail. The Egyptian customs officials had asked to see what was in the merchants’ sack, and the bearers of the apostle had said they were taking provisions to their ship, a pig’s carcass. This had been around the year eight hundred. He meant AD? Heikkilä looked at me over his spectacles like a country schoolteacher. He would certainly tell me when he meant BC. He told me to use my brains a bit and keep up. How could the apostle’s dead bones be carried anywhere in a sack eight hundred years before Christ, seeing as Mark was the author of St Mark’s gospel telling about Jesus’ life? Well, anyway, the customs men had allowed the Venetians to pass. After all, Muslims believe the pig to be a dirty animal. The Accademia apparently also had other Tintoretto pictures about the life of St Mark. I now realized that Tintoretto was a painter, but as far as I was aware the Accademia was a bridge over the main canal. Heikkilä said it was an art museum.

When the apostle had arrived in Venice in the sack, they began to fear that foreign tradesmen in the city would play the same trick and steal the saint in their turn. To protect the evangelist a winged lion was taken from the Assyrians, in order to keep St Mark safe in the republic. Well, it wasn’t yet a republic at that time, Heikkilä frowned and looked up at the inlaid mirrors by the ceiling. I asked what the winged lion was and he gestured through the window to the square. There it stood on a high pillar.

The lion taken from the Assyrians had actually been a pagan statue, but the Venetians quickly made it Christian. Well, they did need a bishop to help. And yes, of course it was already a republic at that stage. Heikkilä tapped his skull with his knuckles. They chose the lion because it had already been the evangelist’s symbol from early times. Now the winged lion could be neatly transformed into St Mark’s protector and the apostle himself was made the patron saint of Venice. Within a short time a large number of copies were made of the statue, and these were erected all over the city for good measure. I wondered what kind of city this is, which even steals its own patron saint.

Heikkilä said the Venetians had stolen everything they hadn’t bought. As merchants, they don’t make anything themselves, they just sell and buy and extract a profit at every opportunity. I picked up my wallet from the counter, where I had put it after trying to pay for the drinks I had ordered. We went out and Harry ran after us shouting and waving his arms. Heikkilä deduced that he wanted payment. I was angry. I told him to tell the man that I had tried to pay for every single glass, but he had not made a single move to take the money. I walked on. Heikkilä stayed behind to discuss the issue.

I sat on the edge of the jetty and Heikkilä came up. He began to explain that the system was such that you didn’t pay for each order separately. The barman keeps a tab in his head for everyone’s orders, and before you leave you are supposed to indicate, with an invisible gesture, your intention to pay. Then the barman slips you a saucer with a written bill. Before leaving, the customer discreetly deposits on the saucer the designated sum supplemented by a percentage corresponding to general usage, plus, at his discretion, a tip in proportion to the standard of service received.

I didn’t think this procedure was any kind of a system. The functional and logical arrangements of Finnish restaurant practice, on the other hand, could certainly be called a system, one which the Italians and other Europeans could indeed adopt to replace their confusing customs. In Finland, goods and money exchange ownership at the counter in real time, and no one needs to acquire a burdensome baggage of mannerisms whereby matters are dealt with by invisible gestures. We gave up tips and extra percentages as soon as we got rid of the Russians in 1917. Tips and bribes have been replaced by Scandinavian social security, pension funds and unemployment benefits. This is how a sensibly organized society works, where ambiguous etiquette has been replaced by clear pricing. The Europeans still have a long way to go. And the more distant they are from Finland, the further they have to go. The prof tried to defend the Venetians: after all, they had invented the market economy. I replied that it was us who had made it function, the Venetians with all their unnecessary customs had got stuck somewhere along the way.

I tried to forget the Italians and concentrate on thinking about what kind of rock the Helsinki region water tunnel would have to be bored through, around the collapse that had been discovered near Riihimäki, and what the results of the drilling and ultrasound tests might be.

January 25.

When I woke up today the weather had brightened.

There is a wind blowing along the Adriatic, shifting the blanket of fog. The sun breaks through and the dampness evaporates skywards. I first intend to stay in bed in the hope that the nebbia will return. Of course I know this will not happen. I get up and go downstairs, where the breakfast has stopped ages ago. But I get up a bit of a flirt on the subject with one of the waitresses, which results in a glass of peach juice, a caffe latte and a wonderful tramezzino sandwich in which the girl seems to have collected everything left over from the breakfast buffet. This modest social achievement takes all my strength. I feel like I’m a hundred years old. Depressed, I realize that heavens, I do indeed have two-thirds of a century behind me.

After my late breakfast I walk out into the town. On the narrow spiral staircase of the hotel I curse the Venetians’ decorative impracticality. I would exchange the master-painter’s skilfully marbled walls and the stylish cast-iron banister any day for a decent lift in which one could descend in a straightforward manner with no fuss. Apropos of practicality: when we were conversing about canals our engineer once expressed his personal view of the city’s characteristic traffic routes. He thought the wisest thing would be to fill them all in and cover them with asphalt!

It is fortunate that our conservative and sentimental hosts did not hear Marrasjärvi’s blunt comments. It is in fact curious that the present-day inhabitants are so loath to accept any innovations that would make life easier in this city, which has undeniably become increasingly inconvenient. After all, the Venetians themselves were originally the most practical of people. The city was specifically built to be an efficient and functional environment, and the canals have been an ingenious and practical solution. Now they no longer serve their purpose. In accordance with the original principle of functionality they really should be filled in and asphalted over, as Marrasjärvi suggests.

At least since the 18TH century the whole city has become an outdoor museum for all Europe. Since the great voyages of exploration and the loss of her trade monopoly with the East, Venice has lost her dynamism and original idea. That is precisely why people who themselves have somehow come to a stop or dropped out of the mainstream of life, like tourists or old people, flock to this place. You can’t achieve anything in Venice, you can only hang around. After all, why have I come here myself? Why does anyone come to Venice? Dying is really the only thing one can do in order to change the prevailing state of affairs. My God, death in Venice is such a theatrical topic, so stifled by literary meanings, even thinking about it makes one irritated.

IV

At the shore people were disembarking from water buses all the time and crowds were beginning to gather in the square. Many different languages were spoken. There were lots of cameras in each group, clicking away. It seemed like someone had begun to pay for taking photographs and video films. People were herded together like cattle, and these groups were shifted about and positioned with shouts and gestures in front of the sights. I tried to calculate how many pictures there might be in the world, of tourist groups on St Mark’s Square, if this had been going on every day, every hour, from one year and decade to another, for as long as cameras had existed.

If fees were paid for taking photos, who would buy all the pictures? Would there be adequate marketing? It wouldn’t take long before the people in the pictures also demanded to be paid, as well as the photographers: more for people in the centre and less for the hangers-on at the edge. The photo sites would be priced, with props available on the spot for sale or hire. Trainers of tame pigeons would muscle in and costs would rise. At some point they would be so high that the soaring price of the final product would meet the market’s pain threshold. A downward spiral would be set in motion, continuing until the cost-benefit ratio once again seemed tempting and depressed photo firms began to recover, like flies beginning to stir again after the winter.

But the Italians would never be able to get anything like this organized. They only managed to arrange that every morning a group of quarrelling traders arrived on the square, hanging around and selling paper cones of seeds. The tourists bought the cones for ridiculous prices and poured the seeds over their heads and shoulders. The pigeons fluttered around any punter who did this and the other tourists took pictures. The traders shouted and gestured and hopped about like big birds themselves. It looked like they had come to the square just for fun, not to work. Other traders had set out their colourful junk on lengths of cloth spread out in front of them. The prof said some of it was world-famous Murano glass. If the local police appeared, the vendors grabbed up their stuff in a bundle and ran off round the corner like thrushes scared by a hawk. It was no kind of organized business activity.

“What are you staring at?”

“I’m thinking about the laws of the market economy.”

Flushed with grappa, Heikkilä leaned his face towards me and waved the palm of his hand before my eyes. The tourist group in front of us had finished getting themselves photographed. It had taken quite a time because each in his turn had left the group to take the photographer’s position with his own camera. In this way the same group was snapped eight times, always with a slightly different composition, and each member could then take home a slightly different picture. This too was one way of realizing individuality. In every picture everyone had a cheap compact camera dangling on a strap from their wrist, as an extension of their hand.

There were also other kinds of photographers. These had reflex cameras and they crept round a pillar or statue squinting obliquely upwards. Many got down on their knees and framed a shot with their fingers as if they were making holy signs. They had additional equipment in their shoulder bags or jacket pockets like fly-fishing anglers; from inner compartments they took out lenses which they screwed to the camera housing to try, and then unscrewed again when the viewfinder picture was nevertheless unsatisfactory. They had no end of small things in their pockets and bags: lens covers, filters, rolls of film and tiny brushes which they used to clean their gadgets like archeologists cleaning objects found at digs. In their search for unusual camera angles these photographers peeked around the corners of buildings, crouched low on the ground or stood on tiptoe on benches or jetty bollards. They all had one eye closed. Heikkilä asked what I was staring at with such interest now. I pointed: the cheek of a fat Japanese man had been pushed so far up over his camera-free eye that the whole eyebrow had disappeared in a fold of flesh.

Heikkilä began to look. It was easy to watch people when they themselves were all looking at the Doge’s Palace as if they were obliged to do so on strict orders. One photographer had gone round two columns and now lay on his back on the ground. A long camera lens rose up from his face towards the top of the column with St Mark’s winged lion. After filming the lion with the camera humming, he got up, went round the pillar again and walked away from the shore to the main square, prowling past the Doge’s Palace on the way. Sometimes crouching, sometimes on tiptoe, he pointed his telephoto lens at the palace windows, the colonnade arches and the ornamental joints of the pillar clusters. With the camera raised to his eye for a vertical shot, his left elbow stuck up into the sky like an upside-down V. Shaking his head vigorously, Heikkilä said the man would soon die.

He pointed a limp wrist towards the columns on the shore. He said the Venetians believed that walking between them brought bad luck. A person who does so will die within the year. That’s what had happened to the Doge Marino Falieri in 1354. The poor chap had disembarked in a fog and stepped between the columns by mistake. The Venetians executed him the next year. I thought there was a logical error here. If the Venetians are in the habit of killing people who walk between the columns, the correct expression is not a belief but a threat. As a prediction it would be self-fulfilling and hence not a proper prediction at all.

According to Heikkilä the columns had also been brought as plunder from somewhere in the east. He was drinking grappa from a hip flask. He had bought a bottle from a kiosk, because in his view we had spent so much procuring an inebriated state at Harry’s Bar that it now had to be maintained. The grappa was expensive at the kiosk, but he said it was worth buying because it was still much cheaper than at Harry’s. In this way we all won, Harry, the kiosk owner and we ourselves. I wondered about the wisdom of buying the grappa, but Heikkilä told me to stop talking about it, as I didn’t understand the mechanisms of the Venetian-style market economy. More and more tourists went by and a lot of pictures were taken of us as well. Heikkilä guessed we had become a picturesque detail in the refined yet decaying Venetian cityscape.

Standing at Harry’s counter had cost over two hundred thousand lira. I don’t know what we would have had to pay if we’d sat at a table. Heikkilä began to laugh when I asked if he knew Harry from before. He explained that of course the man working behind the bar had not been Harry. Harry’s Bar belonged to the Ciprianis, a hotel-owning family; it had been the favourite restaurant of Hemingway, Orson Welles and many other celebrities visiting Venice.

Heikkilä began explaining how Papa Hemingway had spent time recuperating in the city after his African journey in 195 1, drinking at Harry’s Bar and ordering to his room at the Gritti Palace Hotel newspaper cuttings about the plane accident in which he was claimed to have died. I’d seen some of Orson Welles’ films and heard of Hemingway too, but I’d not bothered to wonder what kind of man he was. Why had Heikkilä called him papa? Was he some kind of godfather, taking care of under-the-table betting or illegal trade in the marketplace? I wanted to get away from the hubbub of St Mark’s, to get some rest in a cool dark room. I didn’t want to hear another word about any Venetian family, or the head of such a family, but Heikkilä went on and on.

The water buses arrived and departed from the stop next to us. Heikkilä began feeling sleepy too. I didn’t want to have to carry him along the alleys or lift him into vaporettos and water taxis. I suggested we head off somewhere else and leave St Mark’s. We had now seen it. Heikkilä said we hadn’t seen anything yet. Sitting on a stone bollard he launched into a lecture about the Doge’s Palace, which appeared to unite all styles and architectural movements. The palace had been extended several times, and had occasionally been damaged by fire. Each new style had been combined with the previous one and the final result was something he called a synthesis of Roman, Lombard and Arabic.

In his view this architectural flexibility showed that the Venetians were practical people. I didn’t see much practicality in the Doge’s Palace. The outside surface consisted of a Gothic colonnade reaching half-way up, with a pink wall that reminded me of the Barbie house I had brought back from America for my daughter. Rome and Arabia I knew, but Lombardy was only familiar from Lombardy bread, the name a big bakery had invented for one of its yeast loaves.