6,84 €

Mehr erfahren.

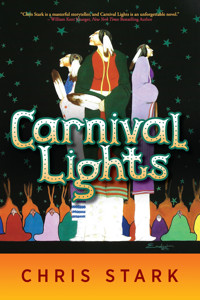

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In August 1969, two teenage Ojibwe cousins, Sher and Kris, leave their northern Minnesota reservation for the lights of Minneapolis. The girls arrive in the city with only $12, their grandfather's WWII pack, two stainless steel cups, some face makeup, gum, and a lighter. But it's the ancestral connections they are also carrying - to the land and trees, to their family and culture, to love and loss - that shapes their journey most. As they search for work, they cross paths with a gay Jewish boy, homeless white and Indian women, and men on the prowl for runaways. Making their way to the Minnesota State Fair, the Indian girls try to escape a fate set in motion centuries earlier.

Set in a summer of hippie Vietnam War protests and the moon landing, Carnival Lights also spans settler arrival in the 1800s, the creation of the reservation system, and decades of cultural suppression, connecting everything from lumber barons' mansions to Nazi V-2 rockets to smuggler's tunnels in creating a narrative history of Minnesota.

"Fluid in time and place, Carnival Lights flows between one past and another, offering a heartbreaking portrait of multigenerational trauma in the lives of one Ojibwe family, this tapestry of stories is beautifully woven and gut-wrenching in its effect. Read it, and it may change you forever."

-- William Kent Krueger, New York Times Bestselling Author

"Chris Stark's newest novel explores the evolution of violence experienced by Native women. Simultaneously graphic and gentle, Carnival Lights takes the reader on a daunting journey through generations of trauma, crafting characters that are both vulnerable and resilient."

-- Sarah Deer, (Mvskoke), Distinguished Professor, University of Kansas, MacArthur Genius Award Recipient

"Carnival Lights is a heartbreaking wonder of gorgeous prose and urgent story. It propels the reader at a breathless pace as history crashes down on the readers as much as it does on the book's vivid characters. The author's brilliant heart restores their dignity and via the realm of imagination, brings them home."

-- Mona Susan Power, author of The Grass Dancer, a PEN/Hemingway Winner

From the Reflections of America Series at Modern History Press

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 505

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Carnival Lights

Copyright © 2021 by Chris Stark. All Rights Reserved.

ISBN 978-1-61599-577-6 paperback

ISBN 978-1-61599-578-3 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-61599-579-0 eBook

Audiobook edition available from Audible.com and ITunes

Modern History Press

5145 Pontiac Trail

Ann Arbor, MI 48105

www.ModernHistoryPress.com

Tollfree 888-761-6268

FAX 734-761-6861

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Stark, Christine, 1968- author.

Title: Carnival lights / Christine Stark.

Description: 1st. | Ann Arbor, Michigan : Modern History Press, [2021] | Summary: "In August 1969, two teenage Ojibwe cousins, Sher and Kris, leave their reservation for the lights of Minneapolis. The girls arrive with only $12 and their grandfather's World War II pack. But their ancestral connections to the land and trees, to family and culture, to love and loss shape their journey the most. They cross paths with a gay Jewish boy, and men on the prowl for runaways. Making their way to the Minnesota State Fair, the Indian girls try to escape a fate set in motion centuries earlier"-- Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021029471 (print) | LCCN 2021029472 (ebook) | ISBN 9781615995776 (paperback) | ISBN 9781615995783 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781615995790 (pdf) | ISBN 9781615995790 (eBook)

Classification: LCC PS3619.T3734 C37 2021 (print) | LCC PS3619.T3734 (ebook) | DDC 813/.6--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021029471

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021029472

With gratitude for Sam Emory and niiyawen’ehn Earl Hoaglund

For the Old Ones

Contents

Prologue

East

South

West

North

The Four Directions

About the Author

Acknowledgements

“I seek the religion of the tree…”

—George Morrison

My girl, every tree tells a story. The Standing People hold the stories of the land. They grow according to what happens around them. Story upon story unfolding, one story growing from other stories.

A tree is a story! Sometimes a story grows off the trunk into a clump like those big bulges you see on trunks sometimes. Those bulges. They’re a part of a story that got trapped there somehow and instead of becoming a branch it just bulged. Who can say how? Who knows? I don’t. Humans don’t know everything. We don’t need to know everything. It’s just how it is, my girl. Clumps. Backwards. Forward. The old days. The days that will come. Stories are not straight lines like how the whites think and write. That is not our way. Stories grow zigzag, branches off branches off branches, shooting in every direction, and more branches off those branches and so on until leaves unfold in the spring, until a story is spoken.

Then, like the leaves, once stories are spoken, they fall to the ground to go back to the earth and the next time the same story is spoken, a new leaf grows, and it is similar, but not exactly the same as the leaf from the year before. My girl, this is how it is—as my grandmother once told me stories, I now tell you stories that you must pass on so that the trees will always have leaves. If the stories stop being told, the trees will have no new leaves; they will die and soon after, so shall we, for we have breath because of the leaves.

The old Ojibwe man paused, focused on the branch he was whittling into a pipe stem. Even in the white world trees tell stories. Crushed flat and bleached. Called leaves! See, my girl. It’s as I told you. Even in their world, trees tell stories. Standing People. Stories. Indians. The land! Howah!

— Clarence Leonard Braun

Prologue

Village of Park Point, August 3, 1860

The carnival came to town, but not until after the Indian bones were excavated. Under the red beam of the Minnesota Point Lighthouse cast by a fourth-order Fresnel lens and illuminated by a kerosene lamp, a motley assortment of Finnish, German, and French men wielding spades and pick axes broke joints, cracked femurs, shattered fingers, and split the skulls of those buried long before Europeans set foot on the shores of the westernmost tip of Gitchi Gami, renamed Lake Superior by the French. A former John Jacob Astor agent in concert with the acting mayor of the unincorporated town of Duluth made the decision to build a carnival to “brighten the dour mood” of the sixty-odd dwelling on the shore and the few hundred in the logging and mining camps nearby. Although it was a hefty investment with questionable immediate return, the two men had plans for the port and needed to attract hundreds, and eventually thousands, more European immigrants to build the city. The two men believed once others heard of the grand carnival held there, Europeans would come in droves. The Europeans were sitting on a gold mine of trade prospects now that they had moved the Indians off the shoreline closer to Fond du Lac. The Indian graveyard had been a problem, though. The men worried someone might kick up a bone during the carnival and cause a sensation, frightening business to St. Paul or Chicago. So the bones were hacked out of the soil by criminal castaways and thrown into a wagon drawn by a single draft horse lent by a man who used the horse to clear tree stumps from the burgeoning township. That is how the Indian bones traveled to their new home, nearly three miles down the river that flowed southward out of Gitchi Gami, the largest lake in the world.

Two days after the removal, guided by the red beam of light, the Arawak steamer brought in supplies—a large metal wheel that hitched to a horse directly across from a wooden bench such that as the horse walked in circles, patrons rode the bench for four spins a penny around a fifteen-foot-wide path. Called the Sweetheart Ride—it was the center attraction for the first-ever carnival on the spit of land overlooking Gitchi Gami. The ride was the motivating factor behind George Washington Gale Ferris, Jr’s invention of the Ferris Wheel, which would make its first appearance at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, commemorating the four-hundred-year anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s landing in the archipelago inhabited by the Taino, and designed to be direct competition to the Eiffel Tower of the 1889 Paris Exposition.

Four days later a four-wagon caravan arrived carrying workers, lard, bags of flour and potatoes and dried pork, canvases, rope, tar, shovels, stakes, and wood that transformed into four tents, including a sideshow of Savage Indian Joe and His Squaw—a Ho Chunk Indian man and a Brothertown mixed-blood Indian woman who looked full-blood. For three days they set up camp, washed clothes on the rocks along the shoreline, mended costumes, and cooked. After considerable labor by the carnival workers that extended late into the evenings under torch light, the townspeople gathered for their first carnival on the Indian cemetery. Based on Mark Twain’s character, the evil Injun Joe who was the villain of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, the Harvard-educated, well-read, former John Jacob Astor agent created the sideshow he called “Savage Indian Joe and His Squaw,” changing the word “Injun” to “Indian” so as to avoid any legal complications with Twain. Savage Indian Joe and his pretend wife rubbed ochre over their faces and arms, donned goose feather headdresses unlike anything any of their ancestors ever wore, and lunged around a tent, waving their hands in the air and screaming gibberish, frightening European women and children alike, who paid a penny to sit on wooden benches and watch the heathens. An old French fur trader familiar with Indian ways looked into the future and knew this wouldn’t end well. The rest enjoyed the frightful show—sucking on the sour, birch, peppermint, lavender, and hoarhound candies while basking in the torch lights that removed the cold and loneliness and hunger they endured thousands of miles from their land, on the other side of the Atlantic. The Indians in the carnival made them feel superior not only to the Red Man, but to the squalor they themselves lived in.

One month later, after the carnival slogged westward over rutted paths, an old Ojibwe Indian lady living in a wigwam far enough out in the woods that the English, as she called all Europeans, had not removed her to the Fond du Lac reservation yet, walked seven miles alone to the site of her parents’ and her parents’ parents’ and her parents’ parents’ parents’ graves. Born in 1784, her grandmother had told her one night when she was a girl of nine that their people knew the time would come when more and more English would arrive, first by ships over water and later by ships in the air, bringing great death and destruction, the Windigo, the cannibal spirit. The old Indian lady’s grandmother told her that the English would make many lights that would guide the ships to the land. One day there would be so many lights they would no longer see the stars and barely know the difference between day and night. “All those lights,” the old woman added, “would make it hard for Indians to see the Star People, our Guardians and Guides, and slowly we will lose our ways. Their lights will steal our people.”

The old Ojibwe lady, then just a girl, stepped outside the wigwam to look at the Star People, hundreds of bright lights in the black sky. Her dog, Animoosh, stood watch at the edge of the clearing. The moon hung full, just over the tops of the bare tree branches, their leaves the size of beaver ears. She couldn’t imagine it—what her grandmother said about not being able to see the Old Ones. She bit a piece of maple tree candy her nokomis had given her and slipped inside the wigwam, nestling into the warmth of her grandmother’s belly and the beaver pelts they slept in.

Decades later, stooped, in a long skirt, with a red willow basket over one forearm, the old Indian lady wandered the shoreline where the carnival had been, occasionally bending over, setting something she picked from the rocky shoreline into her basket. Unseen, except by a curious Finnish boy who watched her, she moved through the Village of Park Point with the boy like a white shadow behind her. Crossing the spit of land into the unincorporated town of Duluth, a stray hound whose Finnish master had died six days after arriving on a ship, leaving the dog to fend for herself, lunged at the old Indian woman and flung the contents of her basket onto the dirt. The old lady yelled words unintelligible to the boy and kicked the dog in the face, scaring it away. Kneeling, she regathered the contents of her basket and slipped behind an English man’s tar paper shack. The young boy ran to where the woman had disappeared. Seeing no one, he searched the ground as he had overheard men discussing their quest for rocks that would make them wealthier than the Czar. Whoever that was, he thought.

The boy’s mother had recently died giving birth to a baby sister who also died. His eight-year-old sister took over cooking and sewing and stoking the fire at night while their father searched for work in the logging camps farther north. The children were starving. Near where the dog bit the old woman, his eye caught a pearly white shape in the dirt. Grabbing it, thinking perhaps it would be the special rock the men had talked about, the boy ran lest one of the men take what he had found. Long and smooth, about the length of the boy’s middle finger, he gave it to his sister, who mistook it for a bird bone and boiled it in the water she’d collected from the Great Lake for their dinner that night. And the next night. And the next.

And then, the one after that.

East

In Ojibwe ways, the east direction is where the Ojibwe come from. It is the spiritual direction.

Pine Township, Minnesota on the Goodhue Reservation, August, 1969

The blazing red and blue light from the cruiser careened off the windows, utensils, and faces of the women and men eating at the truck stop diner. No one paid much attention. Sher Braun moved slowly, paid the cashier—a woman in her mid-twenties who looked ten years older—with one rumpled dollar and some change damp with perspiration. The woman nodded absently, turning her back to the girl and the carnival colors lighting up the inside of the truck stop diner like it was the Fourth of July. Sher took the hunk of homemade corn-bread wrapped in plastic with a red sticker on the side holding it together and put it in her pack along with two damp cans of Coke, some face makeup, a sky-blue Bic lighter, and a pack of gum. The important thing, she thought, was to not panic.

The cop was not there for them. Moving slowly, methodically, she kept her face as impenetrable as those around her: deep caverns of darkness garishly lighted up by each cycle of lights. If they knew at all they thought they were on their way to Fargo. If the APBs were out on them, they would be looking north, northwest, and they were on the southern edge of the Goodhue Reservation zigzagging south, southwest headed to Minneapolis where she knew someone who knew someone, or they could camp out by the river until they found jobs or moved on. Whenever the girls had discussed leaving, Sher had always talked of returning by next spring in time to put the seeds in the ground, with the hope her brother, Jack, would have already left for the war. Kris listened to her cousin, older than her by two months and six days, but she did not reply. Kris was not going back.

Sher strapped the pack over her left shoulder and looked at the woman’s back. She glanced through the empty convenience store section and then again at the women and men eating Paul Bunyan-sized portions of mashed potatoes, peas, gravy, and roast beef and drinking iced tea and Cokes out of red, dimpled plastic tumblers half a foot tall. She walked in a long stride that belied the actual length of her legs, careful to set her heavy steel-toe boots down softly on the concrete floor so as to not draw attention to herself.

Sher saw the cop through the front pane of glass. He walked around to the entrance and opened the door, alarming the leftover brass Christmas bells swinging above the top, hanging down just far enough to be nicked every time someone came or went. She wiped her arm across her forehead and looked down at her nails short and thick after years of drinking fresh raw milk and baling hay and shoveling manure.

The cop stopped and stood in front of the door, blocking her exit. “Girl.”

Sher looked up. The cop met her eyes and looked from her sweatshirt to her jeans to her boots. She saw Injun on his face, in the way his eyes tightened and how his jaw set. She shifted the weight of the pack, nodded, stepped around him, leaned into the door, and walked out.

It was raining outside, a light drizzle, the kind that would be good for the crops right about now. They had enough rain that season to keep things green and growing. Too much rain would do in the crops with mildew and weaken the root systems, and too little rain combined with too much sun could still dry up the crops before harvest. She squinted her eyes to the flashing lights and headed off to the right.

Sher strode across the concrete to the other side of the diesel pumps until she reached some medium-length grass and sparse white weeds with heads as soft as the noses of the young cows back on the farm. She cut up under the dogwood and set foot down a slight hill. The moon hung full and ominous, low in the sky. Sher thought of her grandmother, Ethel Mae Braun, passed over nearly a year now. Ethel had told her granddaughter that “moon” and “grandmother” were the same word in Ojibwe—nokomis. “A bunch of bunk,” her grandmother said when the radio discussed the astronauts’ training schedules, or the date of their scheduled flight, July 20, 1969. She swatted the air with her hand. “Yah, sure. They’re on the moon now planting their flag. White people say anything and take everything.”

* * *

“That you?”

“Yah.”

“Did you get it?”

“Sure did.”

Sher stepped into an old hunter’s shack, the gray boards all but stripped clean of the barn red paint. The door was off and lying on its side. Slivers of moonlight came in all around through the slat boards, warped and cracking apart from one another. She pulled off her pack and set down on an old wooden milk crate turned upside down as a chair. There were the remains of a fire made not too long ago, the circle of small stones and ashes still visible despite the dark.

“Guess someone else had the same idea as us.”

“Guess so.”

Sher unzipped the pack and dug around until she found the Cokes. She set them on the ground. Then she dug around for the corn-bread, pulled off the red sticker, and peeled off the plastic. She draped it like a picnic cloth over the dirt. She put her hand under Kristin’s chin and lifted it up until enough moonlight ran across her face for Sher to see.

“He popped you good this time.”

Kristin pulled her chin away. “Did you get it?”

Sher popped a piece of the corn-bread in her mouth, reached into the bag, and pulled out the face makeup.

“Uh huh,” she said. “These too.” She pulled out the lighter and Trident gum from the pack—a green, stained, army-issued World War II bag that had been their grandfather’s.

The day before they left, Sher had climbed into the barn loft one last time to pull the pack down from behind a rafter, where many times she’d witnessed her grandfather stash it along with a buttery smooth beech tree pipe nestled inside a brown leather and black velour pouch, a brittle turtle shell rattle with a frayed red ribbon braided in black horsehair tail, and faded black and white photographs of two young, dark-complected Indian boys. Sher left the photographs and pipe and rattle, knowing better than to disturb them, but took the government-issued pack.

As a child, up in the loft, when she knew her grandfather was out, Sher had fingered the curled, faded pictures many times over the years, always wondering who the other boy was. One boy was her grandfather—despite his obvious discomfort in both photographs, he still had that impish way about him—head cocked slightly, the left corner of his mouth wanting to pull up into a smile, despite his frown, as if it were running away from the thin slanted white scar that zipped up his chin. His eyes were set to unhappiness, but even in that faded black and white photograph Sher could see the dancing light behind his eyes. His aunties said the night he was born the Northern Lights traveled across the sky and left some of themselves in him.

In one photograph the boys sat on claw-foot chairs, a pedestal between them, and a black curtain draped behind them. Unsmiling, hair cut within an inch of their skulls, stiff gray uniforms that made their arms look like boards nailed to their sides, Sher would have believed it an image from World War II, but they were far too young to have been fighting any war. In the other photograph the same two boys were standing on a dirt road, one black leafless tree behind them, railroad tracks disappearing into the horizon, her grandfather with that frowning, half-cocked smile she’d seen him use a thousand times with white people on Goodhue. To her that look said, despite the unhappiness white people caused and despite his need to protect himself from them, he couldn’t help but shine. The Lights danced inside him.

* * *

“Cool man.” Kristin imitated the white hippie kids she saw on TV or those who showed up at their farm sometimes. Indians called them “wannabes” due to their long hair, factory-beaded headbands and talk of returning to nature where they could be free like the Indians. “Far out. Free as an eagle. Like your people, man,” they’d say. “Stupids,” Ethel would mutter, but she always fed and watered them when they showed up at the farmhouse high, half-starved, and dehydrated from some trippy wilderness hike in the adjacent state forest. Generous was the Indian way. Ethel would not lose her ways out of bitterness.

Kristin pretended to toke. But she did not need to smoke marijuana to escape. Soon her spirit was higher than the moon and the stars above her and freer than the light shining in through the hunter’s slat boards. As she pretended to smoke marijuana, holding the imaginary joint between her forefinger and thumb, she thought of the Mod Squad—the TV show about three hippie youth who escape jail by becoming undercover cops. She watched it if her dad was passed out when it aired. When sober he made her turn off “that damn degenerate hippie show.” Kris loved the trios’ clothes and hair—the white man and woman’s long hair and the black man’s afro—and their language. Outta sight!Foxy! Groovy! As Kris’s spirit meandered above the hunter’s shack, she imagined herself as Linc, the black man, chasing a rapist down an alley at night with the lights of the city behind him. Julie and Pete said, “Dig it, man,” as they caught up to her handcuffing the man she’d tackled. “Solid,” she said, just like Linc always said in the TV show.

As Sher rolled up the sleeves of her sweatshirt, she watched as Kris went far away. Sher was used to it.

“Nah nah nah, nah nah,” Kris sang the opening theme song to Mod Squad.

Sher dragged the disengaged front door back to where it should have been. “Okay, Kris,” Sher said. “Let’s eat.”

The girls ate the cornbread and drank the Cokes and did not talk much at all. They slept on their sides, Kris with the pack under her head and Sher with her rolled sweatshirt under hers.

The morning sun woke them like pinpricks. The girls rolled over and over again. Then sat on the dirt floor Indian style and brushed out their long hair with their fingers. Kristin picked up her Coke can and put it to her lips to get one last drink and then crushed it and threw it into the corner. Sher moved the door back to its side lying position on the ground, slipped on the pack, and walked out of the shack. She moved to the west away from the truck stop diner because she did not want to make a second appearance and draw attention to herself. She walked for a few minutes, stepping over molehills and around dead tree branches and bushes until she reached the creek.

A short hike, for sure, but it transported her to the reservation where nearly every day, unless a blizzard or blistering cold or illness kept her indoors, she ran over her family’s farmland until she reached the railroad tracks that cut between the farmland and the Goodhue State Forest. The forest and the reservation were both named after Goodhue County, actually located in southeastern Minnesota, by a Washington, DC bureaucrat in 1892 who mistakenly thought Goodhue County was a chunk of land in north central Minnesota. The Goodhue State Forest, as described in a 1912 tourism pamphlet, was 111,680 acres of pristine woodland, with “bubbling brooks, the Grand Mississippi, Big Bear Falls, sixteen lakes, and a plentitude of ponds untouched by civilization except for the six primitive campsites constructed by the state for your family’s exceptional enjoyment!”

Originally, the land of the Goodhue State Forest had been set aside as part of the Goodhue Reservation. But when the Office of Indian Affairs opened the reservation to white settlement, the area of the reservation (the northwest quadrant shaped distinctly like a bear’s head, its snout pointed west) that would become Goodhue State Forest proved too difficult to farm.

“Difficult to farm” was the official reason given by government officials about why all the homesteaders had left. While on the surface true, it was not the whole tale behind the Europeans moving off the land. Anyone within forty miles of what would become the Goodhue State Forest had heard the widespread stories told by homesteaders that the land was haunted by ghosts who harangued them by tapping on their window panes for hours day and night, week after week, and year after year. One German man, with the lettered assistance of his wife, wrote the mayor, governor, congressmen, police, vicar, pope (although he was Protestant) and Office of Indian Affairs repeatedly until they finally sent the sheriff to take a report, hoping this would end his complaints. When the reluctant officer paid a visit to his farmstead, the husband stated that the tapping was a perverse version of “Fünfmal Hundert Tausend Teufel” aka “500,000 Devils”. Then he sang a stanza, rapping his knuckles upon the plank board table he’d crafted with his own hands from the oaks that once covered the farm. At the top of his lungs, in slow, broken English with a heavy German accent he sang for the officer:

Tho’ the door is locked and bolted,

Should it cause us to refrain!

Has yet lock a demon halted,

When the keyhole did remain,

the keyhole did remain.

This well pleased the thirsty demons,

who forthwith leaped thro’ the hole

And at once in demon fashion,

wine by thousand bottles stole,

And at once in demon fashion,

Wine by thousand bottles stole

sang their songs in wildest chorus;

Shouting praise to love and wine!

“Is infernal Indian devils. Dem deliver to us insanity in this godsaken land,” the man’s wife blurted out in broken English slathered with such a thick German accent the Swede had to repeat her words three times in his head to understand her. As abruptly as she spoke, she shut her mouth and receded into a corner near the stone hearth. He was a good man, she told herself, didn’t beat her like so many of the others treated their wives, but still, she should watch herself lest she intrude too much into the men’s conversation. Head down, she watched her husband. Despite her twelve years of education compared to his four, and her being a High German, and he a Low German, she still deferred to him. He was the man of the house, the king. “Koenig,” he’d say after proving himself physically—his way of making him more than his wife.

The Koenig stared at the knots in the table, nodded slow. “Ja,” he said. “It’s dem fine. Dem Indian devils.” The presiding officer, a first-generation Swede, wondered how the Indians, with or without their devils, would know the lyrics to some song sung by Krauts, that he, himself, had never heard. The German man glanced at the Swede’s face, the German’s eyes slitted and hard. His cheeks ruddy. The officer thought them insane drunkards, noting the empty jugs behind the barn, once full with distilled spirits. Upon further investigation, he jotted in his report, he believed the jugs had held homemade whiskey, although two smelled of lager. He ended the report by noting that the only spirits at the farm were the ones the husband and perhaps wife had drunk themselves, most likely permanently addling their perceptions.

Two weeks after the Swede’s visit, feeling unheard and disbelieved, the family set loose their two pigs and six one-week-old piglets, two Holsteins, eight chickens, rooster, and three dogs in a frenzy of screaming and clapping. Figuring the animals were tainted by devils, they left shortly after sunrise after yet another evening of terror at the hands of “dem Indian devils.” The only ones who believed them, as their wagon rattled down the rutted dirt back roads toward Bemidji, their long hair flying loose (the husband had stopped cutting his and his wife had not the time to bonnet hers), the reins snapping the back of their horse, and three iron pots clanking, were the Indians they passed.

The Indians knew of such spirits, but only Indians living in bad ways who also had spiritual gifts could summon them. As the Indians watched the Germans—yet another white family fleeing—they argued among themselves about whether it was those bad Indian spirits, summoned or acting on their own, or whether it was the land ridding itself of the intruders, or whether it was the bad spirits those English brought over with them. Only two Indians, up to the point when the German family fled, had been bothered by bad spirits. Wavering between the old and the new religions, and confronted with such terror, they’d returned to the Old Ways, gifted the old Indian doctors, followed their orders, and cleared the curses put on them and their families. What the Indians did agree on was that whatever was happening was happening mostly to the English.

In a twist of fate, the husband’s descent into madness did not end in Bemidji. He spent the remainder of his life in the Fergus Falls State Hospital, hair forcibly shorn by staff and fingernails clipped short so he wouldn’t scratch at his face and neck. Forgotten by his family upon his wife’s immediate remarriage, she and her second husband, a second-generation Swede who owned a dry goods store, raised the two young sons as the biological children of the Swede. Thereafter, the family believed its line to be half Swedish until one hundred and eighteen years later a descendent discovered, upon taking a DNA test, that in fact they were 89 percent German, calling into question the adoptive Swedish father as he was the first in their lineage to claim “Swede.” The widow’s first husband heard she remarried a Swede, and on evenings when his pills hit him just so, causing the shadows to jump at him, he ranted about Swedes, as he’d come to hate them all. The staff tied him down during his Swedish rants, but they knew he’d farmed, and when he was lucid they hoped he would help run the insane asylum’s five-hundred-acre farm that fed the inmates and staff. However, upon bringing him into the fields with the idea he would drive a team of plow horses, he’d begin to rock and then sing in German, grasping wildly at the air around his head as if his hair were long as it was when admitted to the hospital or as if he were battling a horde of bees. After a few minutes of this terror, he’d run. The staff grew weary of chasing him and stopped coaxing him to farm. Never again did his former wife set foot in the countryside. She made sure she and her Swedish husband’s burial plots were in a cemetery in town. And, she hated all Indians.

Other official reports along with widespread stories about the hauntings also discussed banging on doors, turning of doorknobs, dropping squirrels and birds down chimneys, sucking dry milk cows, sticking pitch-forks clear through barn roofs, and mangled and half-eaten livestock. The white homesteaders believed it was the Indians, demons summoned by Indians, a punishment from their Christian God for excessive drinking and/or merriment, and explainable natural disasters such as the locust plagues of the 1870s in southern Minnesota. Thus, after the last white homesteader left the area in 1899 and the railroad built through the area failed, former Governor of Minnesota, US Secretary of War, and Head of the Minnesota State Historical Society, Alexander Ramsey suggested, in 1902, it be turned into a state forest. He wrote in an editorial in the St. Paul Globe about the need to turn the area into a state forest. This wasa turn of events from Ramsey’s typical newspaper of choice, The St. Paul Pioneer Press. Ramsey made a back room deal with James J. Hill, the lumber and railroad tycoon, the Empire Builder, to humiliate the owner of The St. Paul Pioneer Press on Hill’s urging. The men had bonded after Hill sold two men to Ramsey to satiate Ramsey’s lechery, and therefore, in that manner, created an allegiance of secrets between the two powerful men that no one else knew of beside the two men who had lain on their bellies while Ramsey mounted them from behind, thrusting into the men as if they were women.

Hill wanted Ramsey’s statement in the Globe, which he owned, for the simple purpose of rubbing salt into the wounds of Gerald T. Buckley, whose first and last attempt to build a railroad had failed on that acreage near the Braun’s land, and who was Hill’s former confidant and now mortal enemy. Ramsey thought, If this were the old country, we would settle this with a duel. His grandfather had told him stories of gentlemen quick-drawing pistols on one another and how the Crown ended the practice by making legislation that declared anyone present—onlookers and medical doctors—would also be charged with murder. Instead, Ramsey wrote, “This great swath of virgin land has sat entirely unused and languid for three years now. While there is an element of truth to the statements made by some in positions to know that the land has proven to be difficult to irrigate, any growth in population of the area was stymied by the failure of the Buckley railroad built alongside the western edge only to cross east, rather than continue north, through the aforementioned acreage. The failure to establish townships is largely due to the ill-timed pursuit of this venture and the ill-fated course chosen by Gerald T. Buckley, against the advice of James J. Hill.” Ramsey had agreed to focus on the railroad and not on the difficulty of farming the area for Hill’s political purposes, which included humiliating Buckley, who had attempted to undermine Hill’s railroad monopoly. Ramsey concluded, “Our great state must render this area useful by turning the land into a State Forest. It will take but a generation to return the cleared areas to a forested area, as it has been for millennia. This is the most prudent and wise use of this acreage.”

The state forest’s immense body began on the eastern edge of the Braun’s farm. The campsites that were eventually built were on the far eastern edge of the state forest, nowhere near the reservation. The board of Goodhue State Forest, in 1911, nine years after the land was set aside by the Minnesota State Legislature and the official entity of Goodhue State Forest was founded, believed it would still be too dangerous for white families to camp that close to Indian Territory, as some of them jokingly called the reservation at that time. “Not only would it be undesirable, it would also be unrealistic,” Alexander Ramsey boomed across the Minnesota State Senate floor, “to expect the fine citizens of Minneapolis and St. Paul to come within such close proximity to the uncivilized savages.” He doffed his hat and died one year later from congenital heart disease.

* * *

Sher knelt by the creek, unzipped the pack and dug around until she found a small stainless-steel cup. She splashed water on her face, took off her sweatshirt and tank top and washed her breasts and under her arms. Then Sher filled the cup with water and drank. She sat by the creek to dry off under the sun, now around 8:00 a.m. in the sky. After a while she put on her tank top, stuffed her sweatshirt into the large compartment of the pack, and filled the cup with water again. On the walk back to the hunter’s shack she passed over some buried, pink-veined gray rocks set there years ago to form a walkway of sorts. She adjusted her gait to fit the spread of the rocks, as she’d done when walking and running the train tracks back home. She found a sole surviving wild blueberry bush and plucked some blueberries, most of which were small and still hard. The birds had already picked through them. Sher put them in the other battered tin cup.

“That you?”

“Yah.” Sher walked into the hunter’s shack and handed the cup of water to Kristin. She set the cup of blueberries on the ground as their grandparents had done for the girls countless times before.

“Thanks.” Kris drained the water.

Sher nodded. She took off the pack, unzipped the small compartment on the front, and pulled out a wad of bills.

“The depot isn’t far from here,” she said as she sorted the bills with all the presidents’ faces lined up the same way like her father had done when he got the money from a butchered steer or a crop.

“How far?” Kris picked up the cup and stood next to Sher.

Sher looked up at the ceiling mentally mapping their path from her memory of the times she and her pops had traveled the roads on their horses. “I’d say about two hours if we go along the back roads.”

Kristin rocked back on her heels. “It’s only a matter of time before they find out I’m not at your house and you’re not at mine.”

“I’d say another day—tops—if we’re real lucky.”

Kristin nodded and ate some blueberries, picking through them, leaving the hardest ones in the cup.

“I figure,” said Sher, “they’ll look for us on the back roads from Goodhue to Fargo, if they look for us at all, and when they don’t find us there, they’ll put out a statewide APB. On you and me cousin.” Sher smiled, but it was empty.

“They think we’re criminals,” Kris said, as fear of the police and being off the rez rippled through her. The girls were leaving all they knew.

“Some do,” Sher replied.

“Plenty,” Kris said, and leaned into her cousin’s shoulder.

“Yah,” Sher agreed, leaning into Kris.

The girls knew no cop would put out an APB on two Indian girls, but they might do other things to two runaway Indian girls. They had heard the stories, whisperings among the Indian teens, and indirectly addressed by the adults through warnings and behavior. Stay away from the police was rarely directly stated, for Indian children learned to fear them based on the beatings and disappearances and upon what Indians did and did not do: adult Indians and teens’ words ran silent in police presence. Eyes dropped. Indians never called the police, and they avoided the police in town as if they still carried the white man’s plague that had killed so many Indians.

Kristin handed Sher the bottle of face makeup. The girls sat next to each other. Sher pinned the bills under a rock. She smeared the foundation under Kristin’s right eye and across her cheek and then down her jawline to her neck where he held her down and left small red marks. Good thing she’s got light skin, Sher thought with some bitterness regarding all the times white kids and sometimes other Indian kids hassled Kristin over her looks.

“The bruise is hard to cover.”

Kristin pulled back. “Good thing it’s not you. You’d just have white blotches all over.”

“Yah,” Sher said. “Sit still. It needs more.”

When they finished with that, Sher gave Kristin her hooded sweatshirt to cover the marks on her neck. Kristin gathered their things and put them in the pack while Sher slipped the bills from under the rock and counted them.

“Thirty-four dollars.” Sher put the bills in the small compartment of the pack and picked up the empty Coke can Kristin threw in the corner. “Just to be on the safe side,” Sher stuffed it in the pack.

The two girls jogged a jagged line north, northeast to get around the truck stop and then headed south until they hit a dirt road and followed that as it wound about toward the southeast. They walked along the ditch through knee high grass, sharp and green and spear-like, and waist-high weeds poking their wheat-like heads up toward the sun. An occasional frog burped, bellying out its call to its mate. Crickets spoke and grasshoppers flung themselves out from under the girls’ feet at the last moment.

The land was wide open and free, pretty as a picture book. Sher wanted to save it like this, save herself like this forever. The rolling grasses and weeds bent their necks in the wind like the swans and pelicans and black cormorants that graced the ponds on the rez every summer. That, and the flatness of the fields covered with the dainty clusters of yellow and purple flowers crouching beneath the spear-like grasses and nuzzling soft weeds, made Sher feel an eternity inside of herself every time she looked out at the grass and weeds billowing like waves under a pale blue sky.

A car drove by. A brand-new blue ‘69 Mustang with a white C stripe. Not the kind of car they saw on the reservation. The kind Jack, who had moved out with their mother for a few years as a boy when she left the family for long-lost white relatives in New Ulm, wanted except he was half a year away from eighteen and saving whatever little money he could for technical college in Fergus Falls to avoid the draft. It was a losing proposition. Everyone knew he could not make enough to go to college. White boys went to college, at least some of them. But not Indian kids. Sher wondered if the people in the car noticed them, and if they did, would they shoot at the girls the way whites shot at Indians on the interior part of the reservation? Were they close enough to being off rez to not get shot at? What did they think about them trudging through the tall grasses? Probably, she decided, they wouldn’t care about two teenage Indian girls who ran away from home.

“Sure we shouldn’t walk further off the road,” Kristin said, mindful of the practice of whites and their guns.

Sher handed the pack to Kristin.

“Yep. If we cut off it could take a couple of days. Or more. We could get lost and we don’t have food left. This way we get on the bus and as long as nobody questions us when we buy the tickets, we’re in Minneapolis by midnight.” Sher rubbed her neck. She looked at Kris for her thoughts.

“I suppose.”

“This is what I’m thinking,” Sher continued. “Two Indian girls riding a Greyhound into the big city look like we’re going to visit Grandma.”

Sher had watched her share of Westerns with her grandparents and sometimes her dad, when he couldn’t find anything else to do as an excuse to avoid the TV. From the movies she’d picked up a certain cadence and vocabulary which, at times, she unconsciously incorporated into her own such that her style of speaking became a mish mash of long-voweled, lilting Indian-accented English, Minnesota Canadian border white, TV Western, and then, of course, English-accented Indian—what she remembered from listening to her grandparents and other elders talk Indian.

Even though her family watched Westerns, because it was the only place they could see Indians, the TV Indians weren’t much like them, seeming stupid and wooden and unjoking, and not at all like the girls’ grandparents or great-grandparents who’d grown up in the backwoods, real Indians who only spoke Indian and never learned English or Finnish or German or French—the languages of those who took their land. Not like how so many Indians were now, staying put in one place all year long and living off canned rations and government cheese. “We used to be,” the girls’ grandmother, Ethel, would say during the Westerns, tapping her knuckles on the chair’s curved wooden arm. “Not like this, not like this, so,” and she would stare out the window. “In a corner,” she would finish, her gaze returning to the living room. Then she muttered in Indian, and stood up to putter in the kitchen or smoke her stumpy pipe out on the porch overlooking the flat, cleared land that opened into verdant rolling hills and the wide skies of the farm and beyond.

The Westerns were the only time Ethel saw Indians on the little black-and-white Zenith her husband had found in the town’s dump and fixed up himself, using some wire scrap to create a beat-up-antennae that lopped over like a dog ear. She never missed a Lone Ranger episode and thought Tonto good-looking in his fringed buckskin and his thin headband. When teased about that, she turned crimson. “Ehhh,” she said, laughing behind her hand. Disappointed when it went off the air in ‘57, she swore she’d never watch another Western because there could never be another Indian as good-looking as Tonto, but she did watch them on occasion, right up to the night before her and her husband’s old white Chevy truck, which her husband called “Scout” after Tonto’s white horse as a way to tease her, spun off a gravel road into the woods. Whenever he cranked the powerful engine he’d rebuilt, he would yell, “Get ‘em up, Scout,” like Tonto said to his horse, as he thwacked the outside of the door before driving off. “I’m as good looking, eh,” he would say and pose so his wife could see his profile. “Look at that chin. I shoulda been in the movies.” To which his wife would say, “You’ve always been my Tonto, old man,” and then they would laugh, each in her and his own space, chests and bellies rising up and down, laughing at this old joke between the two of them as if it were the first time they’d heard it.

One night the year before the girls hit the road, their grandparents’ truck drove off Highway 212 right at the bend near Point Creek, flipping over four times before it burned upside down, its rear landing on the fork of a pine tree, its cab flattened, crushed into the ground. None but her grandparents, the white men in the truck behind them, the stars, trees, earth, and moon knew what really happened that night. To the rest, it appeared as if an old man lost control, colliding with a single tree with four trunks growing up and outward from its base, spread out like fingers on a hand, as if they’d grown that way just for that night—to catch an old Indian man and woman in full flight. To give them a resting place.

* * *

“I guess so,” Kris said.

“We ain’t gonna get caught.”

“I’m not going back.”

They walked another twenty minutes until they approached a paved road that hit up against the dirt road making a dog leg that would take them south. Sher paid attention to what was around them—the way the tan gravel spread out across the pavement like a fan from car tires kicking it there, the angle the sun beat down on the girls and roads and the cluster of shimmering cottonwoods in front of them, the shiny silky tassels of the corn field to their left, and the way a lone leaf on a sumac bush to their right knocked about as if a strong wind were about to whip it off its stem, even though the other leaves around it were still. When Sher saw the sumac leaf, she thought of times back on Goodhue when she’d been running and noticed a leaf waving about, sometimes quite violently, despite no wind and no movement of any other leaves. She didn’t know if it meant something, and if it did mean something, she didn’t know what. She just paid attention. Even as a young girl, Sher always paid attention.

Sher loved the old stories, especially the ones about the runners who went from camp to camp to call gatherings or warn or ask for help. The first time Sher heard stories about the runners was from her uncle Mo. She didn’t know if they were biologically related, as in Indian ways those called “uncles” and “aunties” could be biologically related uncles and aunties, great-uncles and aunties, or not biologically related at all. “Them old Indians,” Mo said at night when everyone was gathered together, “they had runners who could run faster and farther than any of these...these ah Olympians in their fancy shoes with the little pokers out the bottoms. Yes. Ey. And this one time a little unarmed group of women and children and old, old men out near Porcupine Creek was camping one night, just minding their own ways as the younger men were off hunting, and along comes those who don’t get named and ambushed them, those women and old, old men and little children. And then,” he smacked his palms together, “they ran every which way and the unnamed massacred them even though we had a peace treaty, they did it anyway. They didn’t care about our agreement. That’s what they did. Yes. Ey. But a few escaped and off the runner went, see, always ready to run. That was his job, not to fight, he always had his running shoes, those moccasins, no little poles on them.” He leaned over and waved his hand over the bottom of his foot. “And off he’d go like the wind. Always ready in just a second and he ran up that way toward Gitchi Gami,” and he waved behind him toward Lake Superior, “to our relatives and told them of the deeds and brought back warriors with him to save any who had hidden and to track the group who’d massacred our people, those Indians, they call them a different name now, those white men do, but we called them something else and they tracked them, easy enough to do, and snuck up on them real quiet and got back our people because, you see, they’d taken a few as,” he searched for the word as English was not his first language “as captives and then that there was how the old time runners, they were important to our survival, back then, in the day. Yes. Ey. Yes. Them old Indians didn’t run in circles,” and he waved his hand about and chuckled, “like they do now for no reason except the clock.” He stopped and lit up his pipe and smoked a little. “Things were hard then, but they are hard now too. You see, that is how it was. That is all. Miiw.”

Sher listened. It was like she could see it all when he told the story such that when Sher ran along the railroad tracks and through the narrow forest paths on Goodhue, she imagined herself as a runner in the old days, her people’s lives dependent on her speed and endurance over many miles all alone, and her sure-footed sprinting through snow and ice and heat. And her courage, the courage it would take for her to complete that journey. Yes, that was one thing she liked to think of.

* * *

“Your dad sure is going to be mad when he finds out you’re gone and so’s his drinking money.”

“He sure is,” Kristin agreed.

The girls laughed.

“Imagine him calling my mom and finding out you ain’t been at my house all weekend, then getting mad and going to his Wayne Newton album to buy himself some whiskey and finding out all that cash disappeared, too.”

They laughed harder until they bent over and their eyes teared from laughing and the sun and not having any water. Sher’s long black hair hung nearly touched the ground as she leaned over. Kristin held her brown hair off her face up in a ball behind her head. After a while of laughing like that, doubled over, Kristin threw up.

“Where,” Kris asked as she wiped her face clean with leaves, “is Em?”

Goodhue Reservation, March 1893

The girls’ paternal great-great-grandparents, who spoke only Ojibwe, lost their eighty-acre allotment two years and five months after the passage of the Nelson Act. The Nelson Act turned the tribally-owned Goodhue Reservation into eighty-acre individually-owned allotments. The idea behind it was to force Indians to farm and to force the tribe to sell off the surplus land to settlers. The Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) agent at Goodhue found another way to steal the allotment from the Indians by demanding each family with an allotment show their deed to the allotment. The girls’ great-great-grandparents had not been told to hold the papers, at least not in Indian, and burned the deed in a cooking fire the day after they received it. The map that hung in the Office of Indian Affairs, clearly showed their family as the owners of that parcel, but that did not matter. The OIA agent rose his horse out to the girls’ ancestors’ land. Through a translator, he told their family that due to poor record keeping at the OIA, without papers—no matter the map—nothing could be proven and parcel 84 had been auctioned. All thirty-two living on the land had to be gone by the following day. If not, the Great White Father would bring in the military. That was the official line from Washington, DC; however, the OIA agent knew that before the military were summoned from Fort Snelling, packed their bags and rations, and rode their horses on mud roads 213 miles to the Goodhue Reservation, the nearby settlers would have run off the Indians, shooting any who did not leave. The agent had even heard of a few hangings of Indians down at the St. Croix River, on the shoreline across from Taylors Falls. The white men had let the bodies hang for weeks. After they’d been picked over by crows and turkey vultures, they tossed their bodies on top of the logs floating down the river on their way to Stillwater where the logs were sorted, loaded onto rafts, and sent to sawmills. When the river pigs saw the mangled Indian men, they parted the debarked tree trunks so that the currents would carry the bodies downstream.

Shocked and confused, as this land had been promised to the girls’ great-great-grandparents in perpetuity only a few years earlier, the Ojibwe disappeared into the woods to discuss what they would do without being threatened by the agent or settlers. A week later two young Finnish brothers with hair lighter than straw, their words long and lyrical, not unlike the Ojibwe, arrived and set up camp under the trees. A runner from the Ojibwe camp watched them, and reported back to his family deep in the woods.

The Finns moved onto the land, pushing the Indians to the edge of the allotment, but unlike the other settlers, they did not threaten them with violence and force them to leave altogether. The Indians wondered if maybe they let them stay on the edge because both languages sounded like music, swirling and tinkling like water over bits of ice along the shore of Lake Superior. Their languages were unlike the language of the Indians to the south and west whose words sounded like chewed rocks, hard and guttural, rising from their throat in grunts like the words of the pinched, red-faced men born in Germany, who’d built their new lives on Indian land but still spoke in their old way, many more loyal to the Kaiser than the American leader. The Indians could only guess why they were kinder than the other white people. Despite the land passing legally from one lyrical band of humans to another, they co-existed, uneasily at first, in the woods of northern Minnesota, despite the laws created in that faraway land known as the District of Columbia.

The Finns used gang saws fourteen-feet long that needed two or more men to pull the steel teeth through the ten-foot-wide tree trunks. Then they removed the branches and leaves and hauled the eighty-feet-long stripped trunks on a wagon to the Mississippi. The spines of the trees floated down the Mississippi to the Pine Tree Lumber Company in Little Falls, where the Standing People were cut into perfect straight lines to build square houses. The owners of Pine Tree Lumber Company, Richard Musser, and German immigrant and burgeoning lumber baron Frederic Weyerhauser, who two years later constructed another mansion next door to James J. Hill in St. Paul, built mansions next to each other in Little Falls, overlooking the Mississippi, a stone’s throw from Charles Lindbergh’s home. Unknown to all involved at that time, Musser’s mansion would one day become a museum housing memorabilia from TheWizard of Oz thanks to family friend Margaret Hamilton who played the Wicked Witch of the West and was a frequent guest at the mansion.

After cutting down the white pines, the Finns ripped out the stumps and roots with an oxen team, leaving the roots lying on their sides to dry like twenty-foot spiders, their enormous root-limbs twisted and frozen in time. Once the spider roots dried, they piled them in the middle of the ever-widening clearing and burned them. The massive orange flames licked the ceiling of the sky, garishly lighting up the charcoal night skies for months.

At first, the girls’ family watched the strange English people cut down the trees and rip out the roots. While they were grateful to not be forced off the edge of their land, now owned by the Finns, their grief and sadness over the destruction of the trees and animals who had lived there threatened to overtake them. The Indians began to be sick, like their family at Thatcher’s Trail, who, they learned by a letter meant for them but delivered to the Finns, had all died from “the disease,” including the great-great-grandmother’s brother and wife, or disappeared like the eldest grandson, Leonard. Four months after Leonard disappeared, his mother married a white man from Bemidji so she and her nine young children didn’t starve as they could not survive on their own. The white man took pity, wrote a letter in English, and sent it to “The Brauns, Indians in Antwatin, Minnesota, on the Goodhue Reservation.” The Antwatin postmaster, who was more congenial toward Indians than his predecessor, rode his horse out to the land and handed it off to the Finns, who had one among them who spoke English, who relayed the letter to the one Indian teenager who knew enough English to understand their family had mostly died and those remaining now lived in a city that was the Ojibwe word for a lake with crossing waters.

Vomiting and developing fevers and lacking in energy, the Indians watched entire families of Standing People die until one day the girls’ great-great-grandmother prayed and received instructions for medicines to give to her family. After searching the woods for the medicines, preparing and giving them to her family as instructed, she said, “Sit here. On this side.” So that their family faced the untouched woods, that in twenty-one years would become the Goodhue State Forest. The great-great-grandmother continued to snare rabbits for her family and conduct ceremonies deep in the woods, where no English would see or hear, until her family all returned to health. In these ways, death was not allowed to take up residence in their bodies. As they returned to health, she said, “Look out here. At the forest. Talk with the Standing People. Pray for them. And the animals. And maamaa akii, the land. Pray for your relatives. Don’t give up, my girl. Don’t give up, my boy.”