Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CompanionHouse Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: Comprehensive Owner's Guide

- Sprache: Englisch

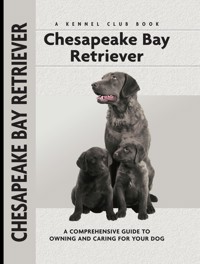

The purebred retriever from the state of Maryland, the Chesapeake Bay Retriever is one of the uniquely all-American breeds. A wavy coat, "deadgrass" coloration, and a strong head give the breed a distinctive appearance; in temperament and personality, the Chessie is equally his own dog. Devoted to his master as a field companion or a family playmate, the Chesapeake Bay Retriever is at once intelligent, level-headed, fun-loving, and a bit of the class clown. Author Nona Kilgore Bauer, an accomplished retriever trainer and a celebrated, award-winning dog author, has written a superb account of the history of the Chessie and eloquently outlined the breed's characteristics in a straightforward, comprehensible way that allows newcomers to the breed to determine whether the Chessie is the right dog for him or her.New owners will welcome the well-prepared chapter on finding a reputable breeder and selecting a healthy, sound puppy. Chapters on puppy-proofing the home and yard, purchasing the right supplies for the puppy as well as house-training, feeding, and grooming are illustrated with photographs of handsome adults and puppies. In all, there are over 135 full-color photographs in this useful and reliable volume. The author's advice on obedience training will help the reader better mold and train into the most well-mannered dog in the neighborhood. The extensive and lavishly illustrated chapter on healthcare provides up-to-date detailed information on selecting a qualified veterinarian, vaccinations, preventing and dealing with parasites, infectious diseases, and more. Sidebars throughout the text offer helpful hints, covering topics as diverse as historical dogs, breeders, or kennels, toxic plants, first aid, crate training, carsickness, fussy eaters, and parasite control. Fully indexed.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 222

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Physical Characteristics of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever

(excerpted from the American Kennel Club breed standard)

Skull: Broad and round with a medium stop.

Ears: Small, set well up on the head, hanging loosely, and of medium leather.

Eyes: Medium large, very clear, of yellowish or amber color and wide apart.

Nose: Medium short.

Neck: Of medium length with a strong muscular appearance, tapering to the shoulders.

Lips: Thin, not pendulous.

Bite: Scissors is preferred.

Muzzle: Approximately the same length as the skull, tapered, pointed but not sharp.

Chest: Strong, deep and wide. Rib cage barrel round and deep.

Forequarters: Shoulders should be sloping with full liberty of action, plenty of power and without any restrictions of movement. Legs should be medium in length and straight, showing good bone and muscle. Pasterns slightly bent and of medium length. Well webbed hare feet should be of good size with toes well-rounded and close.

Coat: Thick and short, nowhere over 1.5 inches long, with a dense fine woolly undercoat. Hair on the face and legs should be very short and straight with a tendency to wave on the shoulders, neck, back and loins only. The texture of the Chesapeake’s coat is very important.

Body: Of medium length, neither cobby nor roached, but rather approaching hollowness from underneath as the flanks should be well tucked up.

Back: Short, well coupled and powerful.

Topline: Should show the hindquarters to be as high as or a trifle higher than the shoulders.

Tail: Of medium length; medium heavy at the base. The tail should be straight or slightly curved.

Hindquarters: Should be especially powerful to supply the driving power for swimming. Legs should be medium length and straight, showing good bone and muscle. Stifles should be well angulated.

Color: As nearly that of its working surroundings as possible. Any color of brown, sedge or deadgrass is acceptable, self-colored Chesapeakes being preferred.

Weight: Males should weigh 65 to 80 pounds; females should weigh 55 to 70 pounds.

Height: Males should measure 23 to 26 inches; females should measure 21 to 24 inches.

Contents

History of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever

Meet the talented and rugged retriever from the shores of Maryland. Learn about the origins and development of the “Chesapeake Bay Ducking Dog,” and follow the breed’s amazing feats in the field, on the water and in competition. Not just a “wavy Labrador,” the Chessie stands apart from the other retriever breeds in both looks and personality.

Characteristics of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever

Steady, intelligent, skilled and loyal, the Chesapeake is without equal as a hunting partner and, with the right owners, as a companion. Do you have what it takes to own, train and provide for the active, sometimes stubborn, but immensely lovable Chessie? Personality, owner suitability and breed-specific health concerns are among the topics discussed.

Breed Standard for the Chesapeake Bay Retriever

Learn the requirements of a well-bred Chesapeake Bay Retriever by studying the description of the breed as set forth in the American Kennel Club’s breed standard. Both show dogs and pets must possess key characteristics as outlined in the standard.

Your Puppy Chesapeake Bay Retriever

Be advised about choosing a reputable breeder and selecting a healthy, typical puppy. Understand the responsibilities of ownership, including home preparation, acclimatization, the vet and prevention of common puppy problems.

Everyday Care of Your Chesapeake Bay Retriever

Enter into a sensible discussion of dietary and feeding considerations, exercise, grooming, traveling and identification of your dog. This chapter discusses Chesapeake Bay Retriever care for all stages of development.

Training Your Chesapeake Bay Retriever

By Charlotte SchwartzBe informed about the importance of training your Chesapeake Bay Retriever from the basics of house-training and understanding the development of a young dog to executing obedience commands (sit, stay, down, etc.).

Health Care of Your Chesapeake Bay Retriever

Discover how to select a proper veterinarian and care for your dog at all stages of life. Topics include vaccinations, skin problems, dealing with external and internal parasites and common medical and behavioral conditions.

Showing Your Chesapeake Bay Retriever

Experience the competitive dog show world in the conformation ring and beyond. Learn about the American Kennel Club, the different types of shows and the making of a champion, as well as performance events and trials.

Behavior of Your Chesapeake Bay Retriever

Learn to recognize and handle common behavioral problems in your Chesapeake Bay Retriever. Topics discussed include separation anxiety, aggression, barking, chewing, digging, begging, jumping up, and so on.

KENNEL CLUB BOOKS®CHESAPEAKE BAY RETRIEVER

ISBN 13: 978-1-59378-338-9

eISBN 13: 978-1-59378-964-0

Copyright © 2004 • Kennel Club Books®A Division of BowTie, Inc.

40 Broad Street, Freehold, NJ 07728 USA

Cover Design Patented: US 6,435,559 B2 • Printed in South Korea

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, scanner, microfilm, xerography or any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the copyright owner.

Photography by Carol Ann Johnson, with additional photographs by:

Norvia Behling, T.J. Calhoun, Doskocil, Isabelle Français, Bill Jonas, Mikki Pet Products and Alice van Kempen.

Illustrations by Patricia Peters.

The publisher wishes to thank owners Patsy Barber, Carol F. Cassity, Johanna L. Dewaldt, Kathleen Luthy, Janet Morris, Ruth Ann Leigh-Phillips & J. R. Phillips and Joanne Silver.

A waterfowl retriever that derives from the Chesapeake Bay area of Maryland, the Chesapeake Bay Retriever performs today with the same spectacular ability as his forebears.

Few Sporting breeds can boast a history as colorful as the Chesapeake Bay Retriever, beginning with a shipwreck in stormy seas off the coast of Maryland and two rescued Newfoundland pups who became legends in the Chesapeake Bay area for their extraordinary feats of courage while retrieving wounded waterfowl. Today the 21st-century descendants of those original “Chesapeake Bay Ducking Dogs” still retrieve with the same prowess and tenacity as their fabled ancestors.

The breed’s ancestry dates back to 1739, with reports of powerful and courageous dogs that retrieved great numbers of shot game from the rough and icy waters of the Chesapeake Bay. Documents from that time tell us about fearless retrieving exploits performed by dogs called water spaniels, a type of dog considered by some historians to be of Spanish origin. In that single respect, all retriever breeds, including the Chesapeake, may share a common ancestry, being descendants of those Spanish dogs. Over the next three centuries, the water spaniels were crossed with various setters, hounds and Newfoundlands to produce the retriever breeds we recognize today: the Golden, Labrador, Flat-Coated, Curly-Coated, Nova Scotia Duck Tolling and, of course, Chesapeake Bay.

The Newfoundland swims at the heart of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever’s origins, according to the popular folklore of the region. The Newfoundland is celebrated and revered around the world, as this postage stamp from Uganda, saluting life-saving water dogs, indicates.

Leaping ahead to the autumn of 1807, two St. John’s Newfoundland puppies were said to be aboard an English ship that was carrying a load of codfish from Newfoundland back to Poole, England. The pups were unrelated and had been selected by their breeder from prime breeding stock. Historians speculate that the pups were probably on their way to the estate of the English nobleman, Lord Malmesbury, who at that time was attempting to develop a specific strain of retriever-type hunting dog.

During its voyage, the vessel encountered a heavy gale off the coast of Maryland and, unable to weather the fierce storm, began to sink. Good fortune prevailed, however, when an American ship named the Canton came upon the scene. The Canton, owned by Mr. Hugh Thompson, was steaming toward its homeport in Baltimore, Maryland, with Mr. Thompson’s nephew, Mr. George Law, one of the passengers aboard. Mr. Law assisted with the rescue of the English ship’s crew and cargo, including the two pups. He subsequently purchased the pups from the English captain and named the black bitch Canton, after his uncle’s ship, and called the male, who was red in color, Sailor.

Arriving at his Baltimore destination, Mr. Law presented Canton to Dr. James Stewart of Sparrow’s Point and gave Sailor to Mr. John Mercer of West River. Although they lived on opposite shores of the Chesapeake Bay, both men were ardent hunters who trained and used the dogs for duck retrieving. Accordingly, Sailor and Canton soon became known on both coasts as exceptional water retrievers. Both dogs had uncommonly thick, coarse haircoats that rendered them impervious to the icy waters of the Chesapeake Bay. Although rather small in stature, the dogs possessed courage, strength, tenacity and endurance that were unsurpassed in duck shooting.

Mr. Mercer also told of Sailor’s eyes, which he called “…very peculiar, so light as to have an almost unnatural appearance, and…nearly 20 years later…many of his descendants were marked with this same peculiarity.” Sailor was later purchased by Maryland’s Governor Lloyd, who used him extensively for hunting as well as for breeding at his estate on the eastern shore of Maryland. Sailor’s offspring became well known for their superior performance as ducking dogs, and for many years were referred to as the Sailor breed.

Canton remained with Dr. Stewart until her death, performing extraordinary feats of strength and courage while at Sparrow’s Point. She was relentless in her pursuit of wounded birds, battling with crippled swans and swimming after wounded ducks for miles through ice and fog. Author T. S. Skinner wrote of Canton, “When she was most fatigued, she climbed on a cake of floating ice, and after resting herself on it, she renewed her pursuit of the ducks.”

Since both dogs were well known for their retrieving ability and their skill and stamina working in the ice-choked waters, they were much sought after by local duck and market hunters. Their progeny inherited their superb qualities and, by the mid-1800s, the breed was clearly distinguishable. Of those off-spring, Skinner wrote, “In their descendants, even to the present remote generation, the fine qualities of the original pair are conspicuously preserved, in spite of occasional strains of inferior blood.”

Although Canton and Sailor were never bred to each other, they are still considered to be the original ancestors of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever. While numerous theories exist about which crossbreedings were instrumental in defining and enhancing the present distinctive qualities of the breed, two requirements were paramount in the breeding of Bay-area hunting dogs: a fanatical retriever and a dull, dark coat to blend with the dog’s surroundings. Thus, many hunting and water breeds would logically have been used as breeding stock.

ONE BREED UNDIVIDED

Of all the retriever breeds, only the Chesapeake has not split into two different types, with one type bred specifically for the hunter and the other for the show ring.

The Curly-Coated Retriever, along with other breeds, has been cited in the makeup of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever. The coat of the Curly certainly may have contributed to the Chessie’s impenetrable waterproof jacket.

Written references indicate crosses with Irish Water Spaniels, Curly-Coated and Flat-Coated Retrievers, some setter breeds and yellow and tan coonhounds. While several types of dog evolved, the superior qualities of the early Chesapeake prevailed. All along both shores of the Chesapeake Bay, a very definite ducking dog emerged, one of superior courage, strength and endurance, capable of mile-long swims, often retrieving 200 ducks a day in snow, ice and heavy seas. Under such extreme conditions, a weak dog simply did not survive.

To fully appreciate the exceptional performance of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever at his work, you must understand the geography of Maryland’s Bay area. The northeastern coastal region in which the state is located is home to harsh winters, with huge numbers of migratory birds flying over the icy waters of the Bay. Indeed, shooting was commonly profuse, frequently with over a dozen downed ducks to retrieve at one time, forcing the dogs to go back again and again to find crippled and wounded birds.

These hardy dogs were in demand by the professional market hunters, whose profession and demeanor necessitated the utmost from a working dog. Gunning in the rough and icy seas of the Bay area was a tough game, and early tales abound about Chesapeakes who gave their lives in frigid waters while they relentlessly pursued, killed or crippled ducks that were drifting away with the tide. It is evident that the Chesapeake that developed in this area was no accident, but rather the result of careful breeding by the hunters and families who valued the breed’s special qualities.

Given their popularity, many great lines of Chesapeake Bay dogs developed during the early 1800s, and the breed became known by several names: the Bay Duck Dog, the Otter Dog, the Winchester Ducking Dog and the Chesapeake Bay Ducking Dog, with the latter name prevailing into the late 19th century.

Evidence points to the Irish Water Spaniel, prized for its athleticism and swimming acumen, as being among the breeds crossed to the Chessie.

In the 1870s, a class of Chesapeake Bay Ducking Dogs was shown at the Poultry and Fanciers Association in Baltimore, with dogs entered from both the eastern and western shores of the Bay. Although unrelated, the dogs’ likeness to one another was so striking that a group of sportsmen pondered the issue of whether the Chesapeake Bay Ducking Dog could be considered a specific breed. Since it had originated in a crossbreeding, they questioned whether a breed bearing similar coat and color could be reproduced every time. They ultimately divided the breed into three classes: the otter dog, which carried a wavy brown coat of tawny sedge coloring; the curly dog and the straight-haired dog, which were both red-brown in color. Thus was born the first recognized, albeit rather loose, standard for the breed.

During the mid- to late 1800s, the Chesapeake Bay Ducking Dog was the favorite of the Carroll Island Gun Club, which was located along the Gunpowder River near Baltimore. Club members hunted over Chesapeakes exclusively and bred their dogs selectively. They often played host to wealthy sportsmen and politicians who had a penchant for serious hunting and hardy hunting dogs, thus promoting the breed’s special qualities beyond their local shores.

For many years, the club held the official pedigree of the Chesapeake Bay Dog, and by 1887 a definite strain had evolved, a dog that carried a dark brown color that faded into reddish sedge. The deadgrass coloration, as one of the Chesapeake’s colors is called today, was unknown at that time. Regrettably, at the turn of the century, a fire at the club destroyed all of their breeding records.

The National American Kennel Club (NAKC) was founded in 1876. The first Chesapeake Bay Dog was registered with that organization in 1878, a male named Sunday, bred by O.D. Foulks and owned by G.E. Keirstead of LaPorte, Indiana. When the NAKC was reorganized into American Kennel Club (AKC) six years later in 1884, it accepted registrations of Chesapeake Bay Dogs, making the Chesapeake the first of the retriever breeds to be recognized by the AKC. For the next 40-plus years, all other retriever breeds except the Chesapeake were lumped together in one class until the AKC finally separated them into the breeds we know today.

The Chesapeake breeding program followed by the Carroll Island club and other gun clubs on the coast appears to have been the greatest influence in the development of a breed of uniform type with distinct characteristics. The intended breed blended the three original types—otter dog, curly dog and straight-haired dog—proposed by that first group of sportsmen. Club members, led by General Ferdinand C. Latrobe, joined with other Chesapeake fanciers to form the Baltimore Chesapeake Bay Dog Club. In 1890, their organization created their own standard for the Chesapeake Bay Dog, and by the early 1900s word of the breed’s prowess as a hunter had spread beyond the shores of Maryland, reaching north and west into Canada and beyond.

GUNPOWDER RIVER DOGS

The early Chesapeake used in the breeding program on the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay was sometimes called the Gunpowder River Dog.

The Chesapeake Bay Retriever became the American Kennel Club’s first registered retriever breed.

The American Chesapeake Club was formed in 1918 by Mr. Earl Henry of Albert Lea, Minnesota. Mr. Henry had bred Chesapeakes since 1888, and by 1901 he had developed his own strain of the deadgrass color. Concerned about rising breed popularity and the future of the breed, Mr. Henry joined with Mr. W.H. Orr of Mason City, Iowa, a Mr. F.E. Richmond and several other fanciers to form a national breed club to protect and improve breed uniformity and emphasize working ability. The group drew up a new standard, which was offered to over 50 breeders in the United States and Canada for approval. The American Chesapeake Club thus became the beacon for the Chesapeake breed, and their standard was accepted and approved by the American Kennel Club. AKC registrations from 1934 show a total of 283 retrievers registered during that year and, of that total, 103 were Chesapeakes, proof that in those days, the Chessie was the hunter’s favored retriever.

A famous photograph of a Chessie retrieving from the water. Interest in the breed grew as fanciers promoted the Chessie as being able to work more steadily under rougher conditions than the Labrador Retriever.

The American Chesapeake Club hosted the breed’s first field trial, for Chessies only, at the Chesapeake national specialty in 1932, 14 years after the club’s inception. During those early years, the Chesapeake competed most ably in all-breed field trials, running against Labradors, Goldens, Curly-Coated Retrievers and Irish Water Spaniels. The specialty field trial continued annually until World War II began in 1941. Then, as happened with all other dog breeds, the war interfered with breeding and breed activities throughout the 1940s.

During the pre-war years, breed popularity spread eventually to the West-Coast states and, in 1920, Mr. Orr furnished breeding stock to breeder William Wallace Dougall of San Francisco, who had taken a fancy to the breed. Other prominent Chesapeake breeders of that time included Iowa residents Harry Carney and D.W. Dawson, and South Dakotans J.L. Schmidt and the famous retriever trainer Charles Morgan.

On the East Coast, Chesacroft Kennels of Lutherville, Maryland had linebred Chesapeakes for 50 years. In 1932, Anthony Bliss of Long Island purchased the Chesacroft operation. Two years later, Bliss became president of the American Chesapeake Club, and his enthusiasm and leadership inspired many Chesapeake breeders and fanciers to establish their own kennels. Mr. Bliss owned 8 of the 40 Chesapeakes who attained championship status between 1930 and 1940.

Despite the hardships of World War II, American Kennel Club registrations continued to increase slowly every year. In 1938, there were only 178 individual Chesapeake registrations; by 1945, there were 427; by 1950, the number had climbed to 543.

During the next several decades, the Chesapeake flourished in all areas of canine competition. Through the 1980s, 7 breed members earned both FC (Field Champion) and AFC (Amateur Field Champion) titles, with 11 FC and 11 AFC titles also awarded. By that time, a total of 11 Chessies had also become Dual Champions, earning their FC and AFC as well as their Champion titles in show conformation, proving that the hunting Chesapeake was also the ultimate example of the ideal standard for the breed.

Those years also saw the Chesapeake competing successfully in the breed and obedience rings, with many gaining bench (show) championships as well as CD (Companion Dog) and other obedience titles. Over 5,000 Chesapeakes were registered annually with the AKC. Although ranking behind its Labrador and Golden cousins, the Chessie still has a stronghold in the US today, with annual registrations around 4,500 and higher in recent years.

ACROSS THE ATLANTIC

As an all-American breed of dog, the Chesapeake Bay Retriever was slow gaining a foothold on other continents. Quarantines were undeniably an issue in the import of dogs to the United Kingdom and other European countries. American servicemen stationed in England during the war occasionally took their dogs through quarantine, with those dogs producing a few random litters. Serious efforts to introduce the breed rested with just a few dedicated individuals during the 1960s and 1970s.

In England, noted Flat-Coated Retriever breeder Margaret Izzard of Ryshot Kennels obtained her first Chesapeake in 1967 from breeder Mr. Bruce Kennedy, a cattleman from Scotland. Kennedy’s litter was out of an American import named Doonholme Dusty, and Mrs. Izzard named her male pup Ryshot Welcome Yank, after his American roots. A strong proponent of the working dog, Mrs. Izzard worked Yank in the field with her Flat-Coated Retrievers, and Yank was always in demand at shoots on coastal estates where water work was difficult.

Looking for a mate for Yank, Mrs. Izzard imported Eastern Waters’ Ryshot Rose from the US, and the two dogs were bred in 1974. From that breeding came Ryshot Yank’s Sea Star, who went on to become the foundation bitch for Arnac Kennels, owned by the Lady Spencer-Smith. Yank’s second breeding was in 1975 to the American import Eastern Waters’ Morac, owned by Mr. J.H.A. Allen of Devonshire, England. Some of these pups and others from the Rose litter were exported to France, Sweden, Denmark and Finland to launch the breed in those countries.

A MULTI-TITLED GYPSY CLIPPER

Dual Ch. AFC Coot’s Gypsy Clipper MH, bred by Carol Anderson and owned by Dr. Tom Ivey, was the first Chesapeake to earn all four of those AKC titles, each representing the top accomplishment in his area of expertise. The Dual Champion title refers to the show ring and field trials, the AFC refers to Amateur Field Champion and the MH refers to Master Hunter.

After the death of Mrs. Izzard in 1975, few Chesapeake kennels remained in operation in the UK by 1977. About that time, breed fancier Sandy Hastings launched her Chesabay Kennel with an Arnac bitch puppy named Arnac Bay Abbey. Two years later, in 1979, Arnac Bay Beck, a sister to Abbey, was purchased by Janet Morris of Wales as the foundation bitch for her Penrose Kennels. Both Abbey and Beck competed on the bench and also worked in the field, and Abbey was the first Chesapeake to run a British field trial in 1979. Although Labradors still dominated in the field-trial circuit, winning most awards, Chesapeakes were quite successful in the working tests.

Although more Chesapeakes were being shown on the bench during the 1970s, the major awards still went to other Gundog breeds (equivalent to the AKC’s Sporting Group). That changed in 1982, when the import Chestnut Hills Arnac Drake was shown at the United Retriever Club show, his first time on the bench since his release from quarantine. Drake not only won Best of Breed and Best Puppy in Breed at that first show but also went on to be awarded Best in Show and Best Puppy in Show over the 300 dogs entered. Drake’s success helped change the course of Chesapeakes in the ring in the UK.

By the following year, Chesapeake fanciers had mobilized and joined together to form a club to preserve the breed’s legacy as a dual-purpose retriever and to organize shows and working tests to promote that end. Lady Spencer-Smith, together with Janet Morris and Joyce Munday, founded the Chesapeake Bay Retriever Club of the United Kingdom. Thereafter several new kennels emerged, with many using Arnac dogs as their foundation stock.

In 1984, the club held its first event, offering bench competition with working tests on the following day, and a record number of Chesapeakes entered on both days. Penrose Bronson, sired by the record-setting Chestnut Hills Arnac Drake and owned by Bruce Gauntlett, captured the Best in Show award, winning over her illustrious sire, who took Best of Opposite Sex.

Until that time, no Chesapeake had won a major field-trial award in the UK. The year 1984 broke new ground for the Chessie as a working breed when Janet Morris and her sedge bitch, Arnac Bay Dawnflight of Penrose, took third place at a Novice any-variety licensed field trial. So historic was Dawn’s accomplishment that a photograph of Dawn and Janet was published in an issue of the magazine Shooting Times. That same year witnessed more achievements for the Chesapeake in retriever working trials. Sharland Coxswain, bred by Joyce Munday and owned by Alan Cox, scored a win in a Puppy Dog stake, which was normally reserved only for professional handlers. Two such accomplishments in one year contributed mightily to a surge in interest in the breed.

The decade of the 1980s was indeed a productive one for the Chesapeake. More field-trial awards were captured in 1985 by the Arnac Bay and Penrose Kennels, with Lady Spencer-Smith’s Arnac Bay Delta and Janet Morris’s Penrose of Gunstock winning several ribbons. Janet Morris also scored again in the breed ring when Arnac Bay Beck of Penrose went on to Best in Show.

The following year, Arnac Bay Endurance, a full brother to the winning Dawn and her sister Delta, was handled to a field-trial win by his owner, Mr. John Barker. Endurance also sired Chesepi Amigo Mio, bred by Barker, and Penrose Eclipse, owned by Janet Morris, both of whom won field-trial awards in 1988. That same year, the breed further advanced as a dual-purpose dog when Lady Spencer-Smith’s field-trial winner, Delta, also won on the bench at the club show.

This handsome English Chesapeake Bay Retriever from the 1930s was a winner in the Derby Stake. Ring, as he was known, was an excellent example of the Chessie in the UK during that period.

During this decade, the focus on breed versatility had attracted several prominent fanciers from other breeds. Irish Water Spaniel breeder Elaine Griffin succumbed to the Chessie and took Penrose Delaware Dimbat of Tyheolog on to win the club show in 1987. Doberman Pinscher breeder Linda Partridge purchased Chesabay Coral of Braidenvale as a working field dog from breeder Sandy Hastings. In 1989, the pair went on to make breed history when they won a Novice any-variety retriever trial, besting a field dominated by Labradors and Golden Retrievers.

Linda and Coral were not finished writing new chapters in breed history, however. Three years later, they shocked the retriever world by winning an Open field trial, which is the most prestigious competitive event in the British retriever world. Coral’s win capped a previous coup for the dual-purpose Chesapeake since Coral’s sister, Chesabay Crystal of Arnac, had won Best of Breed at Crufts in 1992.

The Chessie in the US and beyond has garnered top prizes in field trials as well as in the show ring, demonstrating the breed’s unique versatility and trainability.

Until 1990, Crufts had limited the Chesapeake Bay Retriever to a group of imported breeds under