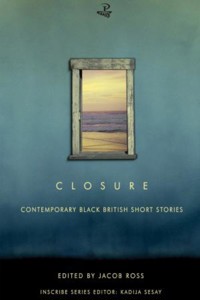

Closure E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

We have always valued the short story as a way to make sense of the world, and our place in it. This anthology by leading Black and Asian British writers is filled with stories, which, like life, rarely end in the way we might expect... JACOB ROSS, KADIJA SESAY, SENI SENEVIRATNE, LEONE ROSS, DESIREE REYNOLDS, SAI MURRAY, RAMAN MUNDAIR, BERNARDINE EVARISTO, MONICA ALI, DINESH ALLIRAJAH, MULI AMAYE, LYNNE E. BLACKWOOD, JUDITH BRYAN, JACQUELINE CLARKE, JACQUELINE CROOKS, FRED D'AGUIAR, SYLVIA DICKINSON, GAYLENE GOULD, MICHELLE INNISS, VALDA JACKSON, PETE KALU, PATRICE LAWRENCE, JENNIFER NANSUBUGA MAKUMBI, TARIQ MEHMOOD, CHANTAL OAKES, KAREN ONOJAIFE, KOYE OYEDEJI, LOUISA ADJOA PARKER, HANA RIAZ, AKILA RICHARDS, AYESHA SIDDIQI, MAHSUDA SNAITH

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 455

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This anthology would simply not exist had it not been for the administrative and coordinating work of Kadija Sesay, Inscribe Series Editor, and the meticulous editorial overview and support of Managing Editor, Jeremy Poynting. And of course Hannah Bannister, Operations Manager – the very paradigm of efficiency and sanity.

Thanks also to the placements and volunteers and staff whose assistance throughout was critical in bringing Closure together: Dorothea Smartt for her encouragement and support of the Inscribe writers included in the anthology, Grace Allen, (internship with University of Leicester), Jade Neilson, Matthew Bourton and Rebecca Patenton.

CLOSURE

EDITED BY JACOB ROSS

SERIES EDITOR KADIJA SESAY

First published in Great Britain in 2015

by Inscribe an imprint of

Peepal Tree Press Ltd

17 King’s Avenue

Leeds LS6 1QS

UK

© Contributors 2015

Jacob Ross

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may bereproduced or transmitted in any formwithout permission

ISBN 13 (PBK): 9781845232887

ISBN 13 (Epub): 9781845233297

ISBN 13 (Mobi): 9781845233204

CONTENTS

A Note from the Editor

Fred D’Aguiar: “A Bad Day for a Good Man”

Karen Onojaife: “Here Be Monsters”

Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi: “Malik’s Door”

Tariq Mehmood: “The House”

Chantal Oakes: “The Weight of Four Tigers”

Michelle Inniss: “Whatever Lola Wants”

Lynne E. Blackwood: “Clickety-Click”

Pete Kalu: “Getting Home: A Black Urban Myth”

Leone Ross: “The Müllerian Eminence”

Gaylene Gould: “Chocolate Tea”

Valda Jackson: “An Age of Reason (Coming Here)”

Dinesh Allirajah: “Easy on the Rose’s”

Sai Murray: “Piss Pals”

Raman Mundair: “Day Trippers”

Muli Amaye: “Streamlining”

Sylvia Dickinson: “Amber Light”

Nanna-Essi Casely-Hayford: “From Where I Come”

Akila Richards: “Secret Chamber”

Louisa Adjoa Parker: “Breaking Glass”

Desiree Reynolds: “Works”

Ayesha Siddiqi: “The Typewriter”

Jacqueline Crooks: “Skinning Up”

Hana Riaz: “A Cartography of All the Names”

Seni Seneviratne: “Hoover Junior”

Patrice Lawrence: “My Grandmother Died with Perfect Teeth”

Jacqueline Clarke: “The Draw”

Mahsuda Snaith: “Confetti for the Pigeons”

Monica Ali: “Contrary Motion”

Koye Oyedeji: “Six Saturdays and Some Version of the Truth”

Judith Bryan: “Randall & Sons”

Bernardine Evaristo: “Yoruba Man Walking”

Contributors

Remembering Kahlil ‘Kahls’ Lewis.Walk good, young fella. You were loved.

A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR

Make up a story… tell us what the world has been to you in the dark places and in the light. Don’t tell us what to believe… show us belief’s wide skirt and the stitch that unravels fear…

— Toni Morrison, The Nobel Lecture, 1993

The two-year process of selecting and editing submissions for Closure presented an opportunity to give some thought to the modern short story, the way it is evolving and the tendency towards increasingly rigid (some may say constricting) definitions placed on the form. It seems to me that over the past few decades much effort has been dedicated to taking the short story from the domain of being a basic human reflex and need for narrative, and relocating it somewhere that is increasingly esoteric. Writers themselves – in interviews and discussions about their art – have at times contributed to this idea of the short story as a kind of visitation experienced only by the lucky or the anointed, whilst contemporary “narratologists” have devoted serious intellectual effort to come up with authoritative taxonomies of the different types of short stories – of which I’ve counted seven so far.

I contend that the short story is simply the de facto narrative mode across human cultures and time: from the oral “folktale”, myths of origin, parables designed to caution, instruct or merely stimulate insight, through to the contemporary written narratives of encounter, trauma, self-exploration and discovery that we find in an anthology such as this. I dare say that, notwithstanding Vladimir Propp’s meticulous contribution to our awareness of the universal mechanics of “story” in Morphology of the Folktale (1928), humans have always understood and valued its role as a way of making sense of the world, and their place in it. Closure is essentially about human striving.

The last anthology that featured short stories by Black British writers appeared fifteen years ago. At the time, IC3: The Penguin Book of New Black Writing in Britain highlighted what Closure still confirms: that there is no shortage of Black and minority ethnic writers engaged with the short story – writers capable of bringing a distinctive and striking fluency to the form. The current spate of short story competitions, prizes and online publishing opportunities is uncovering an undeniably rich seam of short stories by Black British writers. In fact, several of our contributors have been winners of, or shortlisted for, major international, national and regional short story prizes. Interestingly, many of these writers refer to themselves more readily as novelists, poets or playwrights, partly due, one suspects, to the fact that the short story is still perceived as not offering the same career-enhancing opportunities as the other forms of fictional output, in particular the novel.

But perhaps, with dedicated and notable collections of short stories emerging in Africa and the Caribbean by writers such as A. Igoni Barrett, Mohammed Naseehu Ali, Sefi Atta and Doreen Baingana (Africa) Barbara Jenkins and Sharon Millar (Caribbean), the same will begin to happen here.

What stood out during the selection process and the editing of Closure was its richness: of form and voice and tone; of stylistic and thematic range; of the diversity of subject matter, and the varying stances of the writers – ranging from the fantastical, the other-worldly, the speculative and oblique, through to the raw representation of reality.

I was interested in selecting narratives that offered something additional to good writing. I was on the lookout for pieces which, while offering the concentrated intensity expected of the short story, also gave a sense of writers setting themselves challenging places to get to, and wrestling with language or the very form of the short story in order to do it, so that the writing became an adventure. I think there are a good few stories in the anthology that fit this description, but I will leave it to the reader to decide which ones they are.

The writing has moved on from the IC3 anthology, which appeared in 2000. There is less of an attempt by writers – overtly or through their characters – to self-define. “Black Britishness” is what it is – a lived reality that is like air or breath or blood: important, but hardly at the forefront of one’s consciousness except in moments of confrontation or self-assertion, and even then, it is not always recognised as such, as we see in several of the stories.

Here, like the music instructor deciding who she wants to be, are characters more concerned with the treacherous business of confronting their own demons in 21st century Britain than in the injustices levelled against their forebears. They are recognisably contemporary: a successful female stockbroker who finds herself at an abortion clinic with a pop star and an avid churchgoer, each handling her personal crisis; a young Londoner – accosted by a local abductor and potential rapist after a late night rave – attempting to save herself by “stylin” her way out of the danger, Ananse-fashion; a male cleaner collecting abandoned hymens and through this activity learning to empathise with the many oppressions of women; a narcissistic young man who refuses to accept that the time has arrived in his life when the partying must stop and his true self be examined; ghosts who are themselves haunted by their memories of the awful tyranny they suffered in the house they occupy; a young man who cannot find the strength to break from the woman who abuses him.

And there is more – a great deal more – all intensely wrought narratives about humans engaged with the fractious business of life, some of whom are marginally better equipped than others to deal with it. None of them is completely at ease in the world.

Why the title, Closure? We chose it precisely because it undermines itself. Literary fiction is rarely – if ever – about closure. Rather, it is concerned with the opening up of possibilities. At best we are taken to a point of rest rather than a neatly tied-up ending. So, we were interested in the prospect of subversion that a theme/title such as “closure” might trigger in the more rebellious contributor who, we hoped, might say “To hell with all this closure bizness” and dare to offer something different and quite startling. And yes, in this anthology we have stories that were submitted in that spirit!

Good stories are unforgettable precisely because their meanings are not fixed; the pleasures, even the lessons we derive from them gain fresh significance over time. We’d like to believe that the short stories in Closure possess this quality. We hope you think so too.

Jacob Ross

FRED D’AGUIARA BAD DAY FOR A GOOD MAN IN A HARD JOB

Are not the sane and the insane equal at night as the sane lie a dreaming? Are not all of us outside this hospital, who dream, more or less in the condition of those inside it, every night of our lives?

— Charles Dickens, Selected Journalism (1850–1870).

My 250cc Yamaha zigzags through bumper-to-bumper traffic for three city miles of two-finger signs, horns and indecipherable shouts from taxis and buses – the sonic equivalent of a scalpel applied without anaesthetic. Close shave at one junction as a few of us bikers edge to the front of the queue at the lights and accelerate from the pack on the change to green, nearly encountering a car crossing our path. All of it caught on the speed camera. Spooked by this I go slow all the rest of the way to my hospital shift for a 7:30AM start at 7:40AM.

I find Ward Three and try to blend into its routine – well underway without me. Sorry, traffic. Sorry, bike played up. Sorry, accident delay. The nurses from the night shift hand over to the day shift in the stuffy little office. The report comprises mostly of who slept and who did not and who required an extra dose of some cognitive muffler or other to invite sleep, and no news of any new arrivals in the night. The usual routine.

I suppress a yawn. I hear from the night nurses that James slept fine; Cheryl slept fine. That’s it for them. My two charges for my shift both off to a good start after a good night’s sleep. Keep that good luck bouncing my way for the rest of my day. Only hiccup that the night nurses report concerns another ward. One of their patients has gone awol and when the police find him they will bring him kicking, back to where he does not want to be – my ward, since he left the hospital without permission and must upon his return be retained on a locked ward. Maybe the police will take the seven hours of my shift to locate him and by the time they appear with him I’ll be biking out of the hospital parking lot. Keep that good luck bouncing, please.

I walk with another nurse, Katie, as she checks off a name and we dispense, making sure the tablets or liquid match the name and the dose matches the doctor’s prescription. Each patient takes the small plastic cup, throws his or her head back with a thank you or nod or nothing, until we make small talk to hear them talk back – a way of making sure they swallowed. James is perky today. Wants to go and play tennis, asks me if I could accompany him the short walk through the park and across the bridge over the train tracks to the tennis courts. I tell him I will find out from the doctor if that is an okay thing to do. He knows and I know that he cannot leave the locked ward and the constant supervision of nursing staff, because he was assessed as an acute danger to himself after a botched overdose. (He took a bunch of pills and made a call that was traced so that he was found in time to have his stomach pumped and get compulsorily committed to psychiatric treatment.) He took a shine to me; told me as much – that my forehead shone with my keenness as a nurse, which I took as a compliment. He has an ironic charm for a broken human, glimpses of which suggest a will to live rather than give up or opt out or whatever it was Timothy Leary advocated.

James stood there as if I should call the doctor that second. “It’ll have to wait until the doctor does his rounds, James.”

“Okey-dokey,” he says.

Cheryl wears her dressing gown. She knows that when the day shift arrives she should rise and dress and be ready for breakfast. I will have to put that down in her notes and it will be read as a minor setback in her day. In nursing parlance, for a patient to get out of bed and get dressed means a declaration to engage with routine, however humdrum. What seems like one small step for a patient leads to one giant assumption on the part of us nurses, who are on the lookout for any such signs.

“How are you today, Cheryl?”

She says she is fine and opens her mouth lion-yawn-wide to show me that she swallowed the pills.

“I’ll be back for a chat as soon as I finish with the trolley.”

“Suit yourself,” she quips. Oh-oh, what is up with her, I wonder, but I say nothing.

It is always best to say nothing in a profession where words can never be taken back. I look at Cheryl quizzically and glance at her feet and hands for any sign of a disruption in her composure, any dishevelled look to denote a struggle waged against herself in the form of an excessively repeated act, such as washing her hands or doing-up and undoing a cuff button until she tears her sleeve in frustration.

Katie, who stands on the other side of the drugs cart, raises her eyebrow at me and we press on with dispensing. We make small talk between the double checks of names and doses.

“Didn’t I see you at the bar last night?” she asks.

“Maybe.”

“It was you with the Redhead, wasn’t it?”

“Maybe.”

“Did you score then?”

“None of your business, Katie Murphy.”

“You scored, didn’t you?”

“Maybe.”

Another fifteen minutes slips by before I get back to the office with the trolley, and Katie and I secure it in the drugs room. We head off to find our respective charges for a chat, which we will both record.

The nurse in charge heads me off in the corridor and steers me into the stuffy main office.

“Zack, you have to do something about your lateness. Last warning.”

“Yes, Zoe. Promise. You doing okay?”

“I’m fine, except for you being late on my ward all the time.”

“You want me to make up the time?”

“No, I want you to be on time.”

“Will do.”

“Hope so. Keep your ears open and your eyes peeled. We don’t want anyone escaping like that chap from the other ward. I don’t need to remind you that your patients are on suicide watch.”

“No, you don’t.”

“And more details in your notes, please. You’re still too elliptical. I know you’ve just qualified. You almost need to be boring in what you report to get it right. Got it?”

“Yes, Commandant. No, seriously, thanks. I appreciate it.”

“Okay, now get lost.”

“Yes, Commandant.”

“Zoe, wiseass! Unless you prefer Nurse Ratchet.”

She means the totally old school nurse who runs Ward Two just across the corridor (the one from which the patient escaped last night). That nurse would have hauled my ass on report long ago. Old school is jackboots nursing care by numbers, bingo healthcare, fog of drugs; new school is all talk-therapy and a delicate cocktail of pharmaceuticals.

A bell rings. I walk fast to the main office. Zoe answers the phone and orders me – her moon-eyes urgent and clear – to make my way to Emergency Admissions. I run, I walk – like in the Olympics. What is the nature of the emergency this time? They ask for a male nurse to be sent from each of the three open wards. I am not the most senior male nurse on duty on my ward, but Zoe specifically sends me. That can only mean one thing. But I quell my suspicion. Before I reach Emergency Admissions I hear a lone voice shouting what to the untrained ear might sound like unadulterated aggravation, but to my culturally attuned tympanic membrane is none other than that unique mix of adrenaline and scattergun unreason identified with a full blown psychotic episode. A Jamaican accent.

The banging might be feet kicking out or someone falling against corrugated zinc.

I rush into a room whose doors to the street are blocked by a police van, parking lights flashing.

The van’s back doors fling open; a policeman holds them in place as it spills its contents. A black man with a goatee and a tight tangle of waist-length dreads speckled grey, curses very loudly. His cockney herders in uniform shout at him to stop hitting and kicking and they pin him to a wall. He is a big man and solid with it. He pushes from the wall and they all move like a giant spider into a table, and chairs scatter.

He is shouting as he struggles. “I-an-I man free to walk earth as I-man please and nobody can stop I-an-I dread from wandering through Jah creation. For I born free. No chains can hold I-man. I-an-I man walk in peace and wisdom flow from I-an-I pores and Jah power behind everything I-man do. Jah-Jah protection cover I-man back and walk before I-an-I.”

Two other male nurses arrive at the same time as me. I know one, Rollins; the other I’ve seen enough times to nod to him. His name is Smyth. He tells me that this is the patient who escaped last night.

“Does he have a name?”

“Rodney Samuels.”

“There goes my luck.”

The police try to hold the man still across the top of a table and he sputters against a forearm that pins his neck. Remarkably, the man wears handcuffs. With his arms behind his back he still presents a huge problem. The police look at us. Rollins and Smyth look at me. I step forward.

“Mr Rodney Samuels, I’m Staff Nurse Zack Prior.”

I pause to allow for an answer, for a general air of calm to prevail. Nothing.

“Call me Zack. You’re safe now. Do you know where you are?”

I pause again, taking in the man. “Mr Samuels, may I call you Rodney? I will ask the police to release you but you must sit and talk to me or this won’t work. Do you understand?”

He nods. The police ease their grip. They straighten their clothes and remove his handcuffs. One of them stipulates that they will go straight back on if he shows any misconduct. Mr Samuels shakes his arms and massages each wrist. He twists his neck as if righting an untidy stack of vertebrae. He stares at me, his eyes bloodshot and rheumy.

Just as the doctor walks into the room, Mr Samuels shakes his dreads, inhales deeply and resumes, “I walk without fear and only my enemy should be afraid as I-an-I bring down the walls of Jericho and Babylon fall before I-an-I. See the lamb flock to I-an-I. And when I call, my sheep hear my voice and they come to I-an-I. I-man walk in righteousness. I-an-I come to Babylon and I chant with the power of Jah in I-an-I and Babylon fall. So I will reach the kingdom of the most high and rest in His chambers.”

The four police officers suppress smiles and keep their hands on truncheons, pepper spray, handcuffs. They chat among themselves, and with the doctor and nurses as we stand around waiting for the doctor to tell us what the next move should be.

The doctor decides on a course of action that is astonishingly conciliatory towards a man the size and hostility of Mr Samuels. The doctor’s approach piques the nurses’ interest, mine included. We glance at each other and they must wonder, like me, how this will turn out. The doctor is earnest and clear.

“Thank you for everything, Officers. Mr Samuels, my name is Dr Woolicotts. You’ve met Nurse Prior. And you know Nurse Smyth and Nurse Rollins. They’re here for your safety. Do you remember leaving the hospital last night?”

Nothing. Rodney Samuels resumes his invective. “Any man who stand in I-an-I way must fall before my sword and eat the chaff of a whirlwind harvest for I-an-I wield the mighty sword of Zion.”

The doc speaks over him.

“You’re in an agitated state, Mr Samuels. I could prescribe something to help calm you down. Would you be agreeable to that? As you’re aware, you must stay here for 72 hours under our observation. If you try to leave, the police will arrest you and throw you in jail and bring you before a magistrate. You heard the officer. Your best option is to cooperate with us, and together we can get to the bottom of what troubles you. Does that sound good to you, Mr Samuels?”

Perhaps, I, or one of the other nurses, or all of us, should have moved in earlier. The signs were obvious to us, but the teaching hospital we’re in gets these trainee doctors from the world-renowned Institute next door. They turn up and behave like walking textbooks. We chat about it in the pub all the time – the way you can almost see the cogs of their latest untried and untested theory turning as they respond to a crisis.

Rodney Samuels appears to listen to Doctor Woolicotts but he makes a fist. He stares at the doctor but remains worryingly silent. Dr Woolicotts stands with a bit of a smile etched on his face, while he poses questions, pausing between each for a possible answer. For a while the two of them look like they’re in a transaction. The doctor seems not to notice the closeness of his body to that of the agitated man in front of him. My colleagues and I take a small step forward. Mr Samuels glances over at us and the doctor follows his gaze. The doctor actually waves us away. Rollins, Smyth and I take two steps back. I glance at them and they both shrug.

Mr Samuels opens his hands in slow motion and the sight of his bright palms makes Dr Woolicotts, Smyth, Rollins and I relax a little. Mr Samuels raises his arms to chest-level and Rollins, Smyth and I are tense again. Dr Woolicotts maintains his smile and even begins to offer his right hand in a handshake of agreement of some sort.

He’s light years from here, I think. Why should he want to shake your hand?

Mr Samuels leaps high in the air and, with a growl, lands on Dr Woolicotts. The two of them swing and fall and we lunge at them. Mr Samuels lowers his face to Dr Woolicotts and closes his teeth on his right ear. The doctor screams for us to help him. He struggles to shake off Mr Samuels. I hold Samuels’ head in place and the doctor is smart enough, even in his distress, not to pull his head away from the vice of Samuels’ teeth.

Smyth and Rollins each grab one of Samuels’ arms and peel them off the head and neck of Dr Woolicotts. I push my face close to Samuels’ and I shout at him in my most trained voice to let go. I repeat myself. His red eyes meet mine but do not seem to register my presence. This time I add, please. My fingers brush against a steel trap of teeth and saliva. Smyth hugs Samuels’ arm, which brings him up against Samuels’ body and he starts hammering his fist on Samuels’ face while shouting at him to fucking release the doctor. Rollins attaches himself to the other of Samuels’ arms while he uses his free fist to pound the ribs of Samuels. I pull my hand away and a lot of blood spurts from the head of the screaming doctor. I make a fist and am about to land it on Samuels’ mouth when he pulls away from Dr Woolicotts, turns his head to one side and spits a small bloody mass to the floor. Dr Woolicotts rolls away from Samuels, clasps his left ear, stumbles to his feet and slumps to the ground. More nurses pour in and all of us pile on Samuels, holding his limbs and head and sitting on his midriff. He is a strong man. He tries to speak but Rollins punches him in the mouth and he falls silent. A nurse brandishes a restraining jacket and we hitch Samuels into it. Smyth injects the sedative and antipsychotic drug straight into the man’s thigh, I mean right through his trouser leg. Samuels jolts but says nothing. We hoist him onto a gurney, strap him in and two nurses wheel him to the locked ward.

Dr Woolicotts’ colleagues rush in and they administer rudimentary first aid and inject the remains of his ear with a painkiller and antibiotic. One of them gingerly retrieves the bloody piece of ear. They escort Dr Woolicotts to an ambulance that’s always on standby, and with a flurry of sirens it ferries Woolicotts to the general hospital just across the road.

James meets me at the door the moment I unlock it and step into the locked ward. My hands are shaking. I should have joined Rollins and Smyth outside for a smoke.

James looks at me a little puzzled.

“Don’t ask,” I say.

“Okey-dokey. What did the doc say about my game of tennis?”

“James, you’ll have to forgive me but something came up. I’ll get to it now. Where can I find you?”

“Ah, here?”

“Silly question. Catch you later.”

Back in the office I sit with unsteady hands around a coffee cup. Zoe, the charge nurse, pulls a chair up so close to me our knees are almost touching. She stares into my face with her big clear blue saucers. I know that professional look. We’re all trained to do it to optimise empathy and leave the subject in no doubt about the caring nature of our enquiry. But turned on me like this, by Zoe, in such textbook fashion, it fills me with an urge to flick my hands with the coffee cup at her face. Yet I feel compelled, even pleased to tell her the story.

I turn away both James and Cheryl from the office as I write my report of the incident as if it were part of a choreographed scene: strictly motor activity, and the exact words I heard. No impressions, no conjecture.

In keeping with procedure, I meet Rollins and Smyth for a thirty minute session mediated by a psychotherapy nurse. Smyth says he panicked when he injected Samuels through his trousers. He wonders why he did not wait just one more minute while he accessed Samuels’ bare arms by rolling up a sleeve. Says he feels weak for panicking.

Rollins chimes in about his anger while restraining Samuels from doing more damage to the doctor. That he viewed any means at his disposal as necessary to stop what he saw as a grave danger to the doctor. Was he a bad nurse for using maximum force against a fellow human being who was not in control of his normal human faculties? The psychotherapist looks at me. I smile and say everything happened so fast, I felt shock and fear from head to toe and I felt close to everyone in the room except the person who most needed my empathy, but for whom I felt not the slightest affinity at that moment.

They all look at me. I quickly add that I know I share cultural, gender and racial affinities with Samuels, but at that moment I hated him to my core. I even felt shame at his behaviour, I say, that he somehow let the race down by his aggression towards his helpers in the midst of his despair. The nurse looks at me with eyes that suggest there’s nothing they cannot and will not contain.

She nods and says my anger is appropriate and clearly I understand it and own it and Mr Samuels was lucky to have me in his corner.

Rollins and Smyth concur. We sign off and thank the psychotherapy nurse then return to our respective wards. Rollins walks with me a part of the way. He says I should not blame myself; it’s the system that should be blamed for always putting me at the front of the queue whenever a black man was brought in.

“But my presence is supposed to help calm him down.”

“Not in this instance, Zack. The guy was some place where we couldn’t reach him.”

“Yeah, I suppose so.”

“Hey, I hear from Katie that you scored with the Redhead last night.”

“Christ, news travels fast round here.”

“How was the Redhead?”

“None of your business. She has a name, you know.”

“Which is?”

“I can’t remember. See you later for a quick pint?”

“Sure. Will the unnamed Redhead be there?”

“Course not. I mean, I’ve no idea.”

“Later then.”

“Oh, any word on Woolicotts?”

“They’ve stitched it back on. He’ll be fine. Might even start to listen to a lowly nurse as a result.”

Cheryl meets me at the entrance to the ward. She asks about my contacts. I say I woke up late and had no time to put them in. She says I look as if I had no sleep.

“I look that bad?”

She always starts our talks with some personal observation before launching into her feelings of despair modulated by our magic combination of antidepressants, one-on-one talks and therapy.

“Can I talk a little later?”

“But I’ve waited all morning to chat with you.”

“We will talk, I promise, but I need to catch James first.”

“He left the ward a while ago to play tennis.”

“What? Excuse me a minute.”

I run to the main office and find Zoe. I ask her if she knows anything about James leaving the ward.

“He left about fifteen minutes ago to play tennis. He told me you spoke to his doctor, Dr Arbutnot and Arbutnot said it was okay. He showed me a note.”

“No, Zoe, what note? I didn’t speak to Arbutnot. Why would James say that? We’ve got to find him.”

Zoe calls the front desk of the hospital and they say James passed there with a permission slip from his doctor. Her eyes saucer and pool. She grabs her hair and her tone of alarm heightens.

She hangs up, throws the mobile on the desk instead of back into its charging station, snatches it up again and dials the 3-digit hospital emergency number which throws the entire site into emergency mode and alerts the police to be on the look out for a missing patient.

“Zack, find James. Hurry.”

I dash out of the hospital without my leather jacket and regret it the moment I step into the cool autumn air. I shiver and realise it’s not from the cold, but adrenaline. I jog up the street, cut into the park. As I run I look left and right for James. Pigeons scatter from my approach. I take the north exit and bound up the stairs of the footbridge that arches over the railway line. As I cross the old splintered planks of the bridge, I glance at the station platforms, trip and recover awkwardly. On the semi-crowded platforms I pick out a figure in white tennis clothes, standing a hundred yards away. He looks squarely in my direction, lifts his arms and waves. I grab the diamond-patterned wire fence that encases the bridge.

“James! James!”

The train rumbles under the bridge and blocks my view. As it enters the station, its brakes fill the air with a high-pitched whine. A handful of pigeons swoop from the station.

“Zack! Zack!”

I peer towards the other side of the bridge and there is James in white tennis gear, tennis rackets under his arm and a tube of tennis balls held high in the air with the other hand. He looks at me and at the train. He shakes his head and raises his eyebrows to show his surprise.

I run up to him and squash an impulse to hug him and punch him all at once.

“What are you doing off the ward?”

“I secured Dr Arbutnot’s permission myself but I told a little white lie to cover your ass. I told Zoe that you called him for me. You’ve been busy.”

He digs into his pocket and pulls out a green slip. I grab it from him. The date is today’s and the signature resembles Arbutnot’s indecipherable scrawl.

The train pulls away with a hum that rises in pitch as it picks up speed.

“Why would you think it was helpful to me for you to tell others that I said it was okay for you to leave the ward?”

“I like you, Zack, but you are new to the nursing game; you just qualified for God’s sake. By the way, I told Cheryl to cut you some slack. She’s been chasing you all morning. I’m feeling like my old self, even if you can’t see it.”

“I’m glad you’re okay, but I’m mad at you for lying. Let’s walk back.”

“Okey-dokey. The tennis courts are being cleaned so I can’t play anyway.”

“Who were you going to play with?”

“My friend, Mr Charles.”

“Not Mr Charles again, James. I thought you got over him.”

“I tried but he came back for a game of tennis.”

“You and I know full well that there is no Mr Charles.”

“Just a minute ago, on the platform, you saw him wave at me.”

“That was Mr Charles?”

“The one and only. My confidant and tennis partner.”

“We can talk this one through when we get back to the ward.”

“Okey-dokey.”

I dial the ward. Zoe picks up. I tell her to stand down the emergency code, James is fine and we’re on our way.

Zoe meets us at the entrance to the ward. A broad smile makes two slivers of her eyes. She pats me on the back and leads James by the arm to a room for a consultation. He winks at me as he follows her in. I pour myself a coffee and drop into a chair in the office to make a few notes about the incident with James. I call the locked ward to ask about Rodney Samuels. The nurse reports that he’s sleeping; the sedatives have taken a hold on him and he’ll be out of it for days, revived for meals and the toilet, but kept under a strict and heavy drugs regimen. That protocol for aggressive sick people ensures no more violence or break-outs, and amazingly, when patients surface from it, they behave with zest and a keen regard for life.

A rap of knuckles on the translucent plastic pane of the office door makes me look up from my scribbling. A purse-lipped Cheryl with an exaggerated hangdog look stares in at me. I jump up and pull the door open. She waits for me to say something. It’s only a moment’s hesitation but enough for her to turn on her heels and storm off.

“Cheryl, let’s talk, now.”

She spins around and her face lights up. “Really?”

“Yes, right now.”

I walk with Cheryl to a quiet part of the ward, near a set of windows that look out on a patient-maintained garden. Cheryl says she feels better already and asks me how my eyes are doing.

“Fine. How about yours?“

“Not so good. I cried all day and I lost a lens. Washed it clean away.”

“Why the tears?”

“I don’t know; I just feel bad. An overwhelming sadness. Just want to crawl into a hole and curl up in there and never look at the world or anyone again.”

“You woke up feeling that way?”

“No. It just welled up in me when James said he was going to play tennis and I realised I did not want to do anything, and I mean nothing.”

“You are doing a lot, Cheryl. You’re here working very hard, everyday, to get better.”

“But I don’t feel better.”

“It comes slowly. I’ve seen a big improvement. Remember how you arrived curled up like a bean and wouldn’t respond to all my entreaties to you to take your medicine?”

“Nope.”

“You were catatonic. Didn’t blink. Your contacts dried on your eyes.”

“Oh, yes. You used a pipette to drop saline in my eyes with your shaky hands.”

“Yep, and when the lens fell out of my glasses you helped me to look for the tiny screw and you told me about where to get cheap contacts.”

“I remember we never found that screw. Didn’t you use sellotape to hold the lens in place?”

“Aha. Shall we look for that lost contact of yours?”

“Don’t bother. I change them daily.”

“Of course. Did you go to the art room?”

“No, but I will now if you’d just shut up.”

“Right, then. See you later.”

“Thanks, Zack.”

“No sweat.”

I zip back to the office. Katie clasps my coffee in one hand as she huddles over her notes, in a pool directed from the angle-poise lamp. She looks up and says she did not want my coffee to go to waste. I thank her for her consideration. She offers to make a fresh pot and refill my cup. But I tell her to forget it. I let her know that it’s late in the day and I’ll need more than coffee to get over the shift. She gives me a hug, hands my cup to me and exits. I tip my head back and drain the dregs and smack my lips like I’ve just knocked back a shot. I resume my notes on James, with those to be made for Cheryl politely waiting in line.

I turn left from the ward into the main corridor with its six lanes of foot traffic and twin fluorescent strips evenly spaced overhead and unerringly the same lustre, night and day. I tear along at a rapid pace, weaving left and right around more casual folk. Actually, no one who works here is casual; all of us have somewhere to get to by yesterday, but I’m the rabbit with the fob watch able to hop at twice their rate. A drop of water falls off my chin and lands on my shirtfront. I reach into my back pocket for my handkerchief and wipe my face.

I smell the canteen before I see it. The food and the central heating conspire to produce a witch’s cauldron. Yet my mouth waters. I walk in, scan the place for a familiar face, see none and feel glad for the isolation. I join a short queue with my tray and post-9/11 plastic cutlery.

But one look at the congealed rectangular trays of rice and pasta baked under the heat lamp puts me off. I advance to the refrigerated section, choose a triple BLT in shrink-wrap, a banana, a single oatmeal cookie, a small bottle of apple juice and cup of coffee and still the woman at the till says “anything else?” I take my seat in a corner with a view of the exit. I stretch my legs under the table, lean back in the plastic chair and pull out my mobile from my front pocket of my jeans. I dial Katie back on the ward.

“Katie, do me a favour. Have you seen Cheryl?”

“Not at the moment, but I’m at the dispensary. What about her?”

“She’s on the ward, right?”

“I couldn’t tell you. What is it? Should I find her?”

“No, I’ll head back. Thanks Katie.”

“Not sure what I did, but you’re welcome, Zack.”

I gulp my food. I drink the entire 300 mls of apple juice in one tilt. I inhale the banana – I mean divide it into three parts and each third I crush and swallow. I break the cookie into two and wash the halves down with my coffee cup.

Cheryl cries for half the day and in just a few minutes she perks up as if she’d grazed her knee in a playground. That’s too much of a 180° turn even for my nursing skills. Or am I just so plugged into this place I’m unable to take a thing at face value?

Cheryl has never thanked me for anything. She takes all that I have to offer and I leave her and never fail to feel like I could have done more for her, listened better, coined a more inviting observation to engender further disclosure from her. But she thanks me. That can’t be right.

I drop the tray off at the counter section for dirty utensils, recycle my apple-juice plastic bottle, and toss my napkin, free-throw-style, into the wide dustbin beside the exit. I make a quick pit stop at the gents. Wash my hands and rejoin the corridor. It’s about a dozen sets of overhead lights from the canteen to Ward Three. I make two steps to cover each set of pairs and another two steps to close the gap between lights. I know this because Cheryl told me a while back that that was how she made it from the ward to occupational therapy. If she did not count her way along she would feel too much panic to make the short trip. The same mathematical logic powered her life around the ward. At the collapse of that system she took to her bed and her bones locked in foetal pose. She moved so well with her counting system, as I walked with her and talked, that I forgot that she could hold a conversation and still count her way along. I had been so keen to make up for not seeing her all day that I forgot to think about the fact that where we went to sit and talk must have been measured by her, and that as we talked she must have counted out those steps without variation. To break up her code we sometimes practised walking up and down and deliberately taking an extra step after she arrived, and rather than having to start the whole thing all over again I’d get her to talk to me about something – anything long enough for the anxiety to quell, hence our detailed and repetitive discussions about contact lenses.

I take a right into the ward and Katie tells me she looked for but could not find Cheryl and she wonders if Cheryl might have gone to art, psychotherapy, or some other appointment. She is still saying something to me but I turn and run to the front desk at the hospital entrance. I jump to the front of the queue of three people, announce that it is an emergency and ask the porter if a patient fitting Cheryl’s 5' 5'', shoulder-length frizzy brown hair, thin with a prominent nose and slightly red blue eyes left here in the last quarter-hour or so. The porter scratches his head.

“Was she wearing a red cardigan?” I ask.

He nods.

“Are you sure?”

“Of course I’m sure.”

I run to the station for the second time that day, but this time I hear sirens. I turn into the park. Pigeons flare up around my feet. I bolt for the north exit and meet people coming from the station. I listen for the sound of a train, thinking I might hear the wheels on the track as it pulls away, but the traffic from the nearby road drowns everything but the sirens. Passers-by talk excitedly; some cover their mouths or wipe their eyes. I stop an old man in a hat and long raincoat. I ask him what’s wrong. He pulls his arm away from my grip, lifts his hat and runs his hand through a mop of silver. He gestures with his hat at the station.

“A young lady…” But he doesn’t say anymore. He tugs his hat forward on his head and leaves me on the spot.

KAREN ONOJAIFEHERE BE MONSTERS

Arike’s Daily Plan of Action:

Drink herbal teaTen minutes of each of the following, every morning:a) meditationb) yogac) writing positive thoughts in journald) looking in mirror while repeating positive affirmationse) listening to life-affirming songsTreat others as you would like to be treatedSurround yourself with positive things and peopleEngage in a spiritual practiceExercise!2 likes, 0 comments

*

It’s the summer. You start to think about your chakras.

You are committed to becoming your best self. You are not going to care that everyone else is getting married or getting promoted, or having babies or buying houses. When friends tell you their good news, you will simply smile and then send them gift baskets of baked goods because your heart is a lighthouse, as opposed to say, a black dwarf star, colder than Alaska.

You make an action plan and you post it on this blog, for the sake of accountability. You have precisely ten followers, so if you mess it all up, hardly anyone will know.

You pick a Monday morning to start. By the time you’ve had your tea, meditated, yoga’d, journaled, affirmed yourself and listened to upbeat songs, you’re late for work. You dash into the office, stressed as fuck and you imagine your chakras curling like week-old lettuce.

“What would Oprah do?” you ask Tieu Ly when you call her later that day.

“She would write a cheque to her hurt feelings, dreams and aspirations,” Tieu Ly says.

This is an example of why you don’t tell Tieu Ly everything and why you most certainly will not be sharing the details of your action plan. Your best friend can be an emotional terrorist.

*

Things Arike is scared of:

DyingDying aloneDying before having the chance to clear browser history5 likes, 2 comments

*

It’s still summer. One of your teeth just crumbles in your mouth while you are eating a Toblerone. You are forced to go to the dentist for the first time in years and he tells you that the tooth has to be extracted. You are consternated because:

a) who wants to hear that kind of thing and

b) your dentist is very good looking.

It seems cruel that the one time that you have a legitimate reason to be close to someone like this, he is charged with the task of looking into your decaying mouth.

“Let’s talk about your diet,” he says.

You don’t feel like talking about the cakes, sweets and chocolate that you eat and eat every day, but only when you are by yourself. That you eat until your stomach is a tight, anxious drum and your mind is a flat, sleepy haze. Besides, you never throw up. That would mean you have a problem.

“I like the odd sweet every now and then,” you say.

He swivels away in his chair, in an attempt to disguise his eye roll, while you wonder when you developed a taste for wildly pointless lies.

He listens to Shostakovich while he works. As he creates a temporary filling, you are already thinking what to tell your friends. You know you will make something up, because to explain that your teeth are rotting out of your head because of something that you did is too forthright and truthful.

*

Arike’s online dictionary

“Leap and the net will appear” – an utterly meaningless phrase. Speakers of sentences such as this should be bestowed a swift chop to the throat.

7 likes, 0 comments

*

Your chakras will not realign themselves and so you turn to self-help books, but these tend to make your chest grow tight with rage. The books all seem to have been written by and for those with no concept of real life. It’s easy to have an epiphany concerning one’s spiritual purpose while residing at an ashram, herding goats on an Italian hillside or building wells in a West African village. You are yet to ascertain how any of the “lessons” these authors impart can be applied to your existence in a poky flat in Haringey that you can barely afford.

It seems to involve a lot of magical thinking and the last time that worked for you was when you were six years old. You happened to say out loud that you were hungry and your father, who was passing by, agreed to make you a cheese sandwich.

“It’s not you,” Tieu Ly says later that evening, when she calls you from LA. “The people who write these books don’t come from immigrant families.”

You think of your own parents, whose thirst for risk was exhausted five decades ago when they crossed an ocean to come to live in this cold place. The stuff they went through they barely ever talk about. But if you were to tell them now that you wanted to resign from work so that you could write? Fiction, of all things? All your aunts and uncles in Nigeria would agree that you had murdered your parents.

Like you, Tieu Ly did what she was told (in her case be a doctor, in your case, an accountant), as opposed to what she wanted. Still, she consoled herself by moving overseas to practice medicine. That way, she can tell herself that their victory (and by implication, her defeat) was only partial.

As old as you are, you still don’t like to disappoint your parents and they are happy not to be disappointed. See? It all works like it’s supposed to.

*

Arike is: not in love with the modern world

4 likes, 0 comments

*

There are so many things that you love about having a job, save for the actual job itself. The office is That Place and your life outside it is Everything Else. You spend between 8 to 11 hours a day at That Place and a lot of the time you think you manage it pretty well. By manage you mean that you are able to maintain a reasonable façade despite the fact that you feel you are on the verge of fucking up on an epic scale at any given moment.

This is what you are thinking about as you make your way to work this morning, and so you almost walk past the two kids squalling on the pavement, a worried woman standing next to them. They are two little black kids and the woman, white, is in her early twenties. She asks them questions in a soft voice but this just makes them cry even louder. You’re tempted to keep walking because you’re already late, but you imagine your nephew and niece standing there and you come to a halt.

They are brother and sister, both under ten. You work out that they got off at the wrong bus stop and so have no idea how to get to school. They don’t know their address, they don’t know anyone’s phone number; all they have in their satchels are sandwiches and colouring books. They are holding hands like something out of a fairytale, except there are no breadcrumbs in a forest, just dog shit on asphalt and the relentless scream of traffic along the main road.

Eventually, you and the woman decide to call the police. The kids have stopped crying now, but the older one, the boy, has a look on his face that says he knows he’s going to catch a world of trouble for getting lost. You want to fold him into you until he stops worrying, but are aware this would be alarming. So, instead, you tell him about the time you got lost when you were a kid and how you thought you’d get in trouble too, but that your mum was so happy to see you, it’s like she forgot to be angry.

He doesn’t look reassured, so you tell him not to worry, but then you don’t know his life. You reflect that it’s adults coming on like they know everything that leaves kids fucked up. The amount of lies kids must hear before they’re ten years old, just so an adult can have the satisfaction of making them feel better! Or for the adult to make themselves feel better. Because, maybe, that’s what you wanted more than anything else. Not to have to think about what might happen to that kid when he got home.

The police finally arrive – two white men, one old and one young, in a squad car with tinted windows. They are nice enough but it makes you wince when they make jokes about putting the kids in the back of the car. The little girl smiles the way kids smile when adults say funny stuff that they don’t understand, and the boy just looks up at the clouds out of the corner of his eye.

The officers make more jokes about the kids being excited to go for a ride, and perhaps they are, though maybe these kids have heard bad things about the police and maybe ten years from now the boy will be stopped and searched every other time he steps out of the house. You think that maybe you’re the crazy one for thinking these things, seeing that the three other adults in this situation are just standing around and laughing because problem solved, job done.

Back at your desk you get a client call. You give out your e-mail address, which includes your first name. You spell it out for what must be the thousandth time this year.

“Oh, that’s a nice name!” the client says. He asks you where it’s from and you tell him. When he asks you how long you’ve been here, you’re confused.

“At this firm?” you ask.

“No, no, in the country?’