6,84 €

Mehr erfahren.

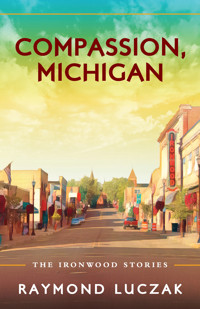

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Encompassing some 130 years in Ironwood's history, Compassion, Michigan illuminates characters struggling to adapt to their circumstances starting in the present day, with its subsequent stories rolling back in time to when Ironwood was first founded. What does it mean to live in a small town--so laden with its glory day reminiscences--against the stark economic realities of today? Doesn't history matter anymore? Could we still have compassion for others who don't share our views?

A Deaf woman, born into a large, hearing family, looks back on her turbulent relationship with her younger, hearing sister. A gas station clerk reflects on Stella Draper, the woman who ran an ice cream parlor only to kill herself on her 33rd birthday. A devout mother has a crisis of faith when her son admits that their priest molested him. A bank teller, married to a soldier convicted of treason during the Korean War, gradually falls for a cafeteria worker. A young transgender man, with a knack for tailoring menswear, escapes his wealthy Detroit background for a chance to live truly as himself in Ironwood. When a handsome single man is attracted to her, a popular schoolteacher enters into a marriage of convenience only to wonder if she's made the right decision.

RAYMOND LUCZAK, a Yooper native, is the author and editor of 24 books, including Flannelwood. He lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

"These are stories of extremely real women, mostly disappointed by life, living meagerly in a depleted town in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Sound depressing? Not at all. Luczak has tracked their hopes, their repressed desires, and their ambitions with the elegance and precision of one of those silhouette artists who used to snip out perfect likenesses in black paper; people 'comforted by the familiarity of loneliness,' as he writes." --EDMUND WHITE, author of A Saint in Texas

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 365

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Advance Praise forCOMPASSION, MICHIGAN

“These are stories of extremely real women, mostly disappointed by life, living meagerly in a depleted town in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Sound depressing? Not at all. Luczak has tracked their hopes, their repressed desires, and their ambitions with the elegance and precision of one of those silhouette artists who used to snip out perfect likenesses in black paper; people ‘comforted by the familiarity of loneliness,’ as he writes.”

—EDMUND WHITE, author of A Saint in Texas

“Filled with grief and hope, bitterness and tenderness, Raymond’s collection of short stories exudes compassion for its characters and their environs. With a confident eye to detail, and knowledge of the pulse of the place, he brings the reader into the quiet lives the people in the stories appear to be living only to reveal internal tensions around sexuality, belonging, and family. A pleasurable, nuanced portrayal of life in a small town by a talented writer with an understanding of the humanity we all share.”

—CHRIS STARK, author of Nickels: A Tale of Dissociation

“Raymond Luczak’s Compassion, Michigan is a modern-day version of Winesburg, Ohio that proves William Faulkner’s statement that ‘The past is never dead. It is not even over.’ These stories describe a small town over the course of the twentieth century, experiencing change, being haunted by its past. Its residents live their lives of quiet desperation as queer, confused, disempowered or outcast members of their community. They seek love, sex, purpose, and the freedom to be themselves. In short, they are human, and they have much to teach us.”

—TYLER R. TICHELAAR, Ph.D. and award-winning author of Narrow Lives

Also by Raymond Luczak:

FICTION

Flannelwood

The Last Deaf Club in America

The Kinda Fella I Am

Men with Their Hands

POETRY

Once Upon a Twin

A Babble of Objects

The Kiss of Walt Whitman Still on My Lips

How to Kill Poetry

Road Work Ahead

Mute

This Way to the Acorns

St. Michael’s Fall

NONFICTION

From Heart into Art: Interviews with Deaf and Hard of Hearing Artists and Their Allies

Notes of a Deaf Gay Writer: 20 Years Later

Assembly Required: Notes from a Deaf Gay Life

Silence Is a Four-Letter Word: On Art & Deafness

DRAMA

Whispers of a Savage Sort and Other Plays about the Deaf American Experience

Snooty: A Comedy

AS EDITOR

Lovejets: Queer Male Poets on 200 Years of Walt Whitman

QDA: A Queer Disability Anthology

Among the Leaves: Queer Male Poets on the Midwestern Experience

Eyes of Desire 2: A Deaf GLBT Reader

When I am Dead: The Writings of George M. Teegarden

Eyes of Desire: A Deaf Gay & Lesbian Reader

Disclaimer

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Even though celebrities and historical figures may be used as characters in these stories, their actions or dialogue should not be construed as factual or historical truths.

Copyright

Compassion, Michigan: The Ironwood Stories

© Copyright 2020 by Raymond Luczak

ISBN 978-1-61599-527-1 paperback

ISBN 978-1-61599-528-8 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-61599-529-5 eBook

Cover Design: D.E. West, ZAQ Designs & Publishing

Front Cover and Author Photographs: Raymond Luczak

Back Cover Photograph: “Iron Mines, Ironwood, Mich.” (Detroit Publishing Co.)

All rights reserved. No part of this book can be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission. Please address inquiries to the publisher:

Modern History Press

5145 Pontiac Trail

Ann Arbor, MI 48105

Toll-free: 888-761-6268

Fax: 734-663-6861

E-mail: [email protected]

Web: modernhistorypress.com

Distributed by Ingram (USA/CAN/AU) and Bertram’s Books (UK/EU).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Luczak, Raymond, 1965- author.

Title: Compassion, Michigan : the Ironwood stories / Raymond Luczak.

Description: First edition. | Ann Arbor, Michigan : Modern History Press, 2021. | Summary: “The author presents 16 stories centered in the locale of Ironwood, Michigan. The stories span more than a century and take the reader on a journey through Ironwood’s boom years as a major iron ore mining operation in the 1930s, its subsequent decline in the 1950s, and the conditions of present day. Focus on LGBTQIA issues of sexuality, gender, and overcoming repression”-- Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020032359 (print) | LCCN 2020032360 (ebook) | ISBN 9781615995271 (paperback) | ISBN 9781615995288 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781615995295 (kindle edition) | ISBN 9781615995295 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Ironwood (Mich.)--Fiction. | LCGFT: Short stories.

Classification: LCC PS3562.U2554 C66 2021 (print) | LCC PS3562.U2554 (ebook) | DDC 813/.54--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020032359

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020032360

FOR

Vivien Arielle Luczak

Stories

Numbers Six and Seven

Stella, Gone

Bargains at St. Vincent de Paulís

The Love Whisperer

Such a Good Boy

My Same Old, Same Old

Yoopers

The Sacrament of Silence

The Traitorís Wife

Frizzy

Absolutely No Talent Whatsoever

The Ways of Men

Molly

Beginnings

Elegie

Independence Day

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About Modern History Press

“Being unable to tell your story is a living death and sometimes a literal one ... Stories save your life. And stories are your life. We are our stories, stories that can be both prison and the crowbar to break open the door of that prison; we make stories to save ourselves or to trap ourselves or others, stories that lift us up or smash us against the stone wall of our own limits and fears.”

—Rebecca Solnit, The Mother of All Questions

“If something happens you will be able to write the book that I may never get written. The idea is very simple, so simple that if you are not careful you will forget it. It is this—that everyone in the world is Christ and they are all crucified. That’s what I want to say. Don’t you forget that. Whatever happens, don’t you dare let yourself forget that.”

—Sherwood Anderson, Winesburg, Ohio

“Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a harder battle.”

—Plato

Numbers Six and Seven

ONCE UPON A time we seven siblings breathed and lived and played together as a single organism. We had names, but we never thought of ourselves as truly separate beings. We moved as one wherever we went. People around town always said, “Look at ’em Forester kids going off again.” The common joke was that our parents hadn’t known when to stop making babies. We didn’t understand why these strangers would cackle with a gleeful wink, but we didn’t care. There was always something new to discover in our backyard or the next one beyond that.

Sometimes we pretended to be mountaineers climbing Mount Everest, which was nothing more than a face of crag shaved off the side of a hill two blocks away from Norrie School. We carried up heavy backpacks, stuffed with pillows and sleeping bags even though we had no need for them in broad daylight. The boulders were easy to conquer, so we yelled, “Look out!” just to spook each other for giggles, and we jumped around and whooped it up once we got to the top. We talked about how we would hop on the next rocket from Cape Kennedy and shoot off for the moon where we would boing like balloons and leave behind big footprints and wave back at the earth looking like a pretty marble. We didn’t have an U.S. flag to stake and claim the moon as our own, but we were already plotting our next adventure.

Below us was the only world we knew then: the tree-lined cave-ins and St. Michael Church’s steeple rising out of the low skyline of Ironwood on our right, and the small and sloping hills of our neighborhood where houses were mostly hidden by enormous trees straight ahead of us. We were never happy that we couldn’t see our own house from our mountain. We tried using a pair of binoculars once. Too many trees in the way. We never climbed the mountain in winter because it was caked with dribbles of ice. We relished each snow day by piling on layers of clothes, scarves, threaded mitts, snow pants, and snowmobile boots, and heading out to the backyard where snowdrifts, whipped to great heights by blizzards, awaited our conquest. Sometimes we could not move quickly so we fell backwards and tasted the snowflakes falling on our faces. We made snow angels. If the snow had the right stickiness, we made snowmen.

In the summer, we took particular pleasure in taking shortcuts through other people’s yards and stealing handfuls of sugar snap peas from their gardens and clapping our hands at the chained dogs just to get them to bark like crazy. Sometimes the neighbors scolded us, but we laughed it off and headed toward Norrie School. It was our favorite place. It had a huge playground with tall swings, monkey bars, and a basketball court. The school was tall and wide with august-colored bricks, and a very tall chimney was stuck in the middle of its roof. Winters it puffed out a great deal of smoke, and every late morning we could smell the cafeteria food wafting from the south hallways where the gymnasium was. It housed kids from kindergarten all the way up to eighth grade. We siblings passed each other in the hallways and on the playground every day, but we never said hello. It was somehow understood that all seven of us would gather near the side door on the west side and walk together the four blocks home. We felt better together.

Such is the story I’d like to believe about the family you and I grew up in.

FOR A LONG time I didn’t know the names of our siblings: Victoria, Patricia, John, Will, Colleen, me, and you—five girls and two boys. I knew them first by their faces and by the way they moved their lips. I thought it was odd how they opened and closed their lips in so many different ways. I looked at myself in the mirror and tried to do the same thing, but my lip movements looked nothing like theirs. It was easier not to use my lips. It was more fun to chase them all over the house.

Our parents stopped and looked at me one day. Their faces said an entire story in less than a second. Something was wrong.

Eventually I was outfitted with a pair of shiny and heavy boxes cloistered in a harness strapped across my chest. The big fat molds that fit inside my ears began to hurt after a few hours, and I took them out and hid them in my pockets. No one told me that I had to keep them in my ears, not until it was time to eat. Mom scolded me each time for taking them out. She gestured that I had to put them back in. Sometimes they hurt so much I cried.

Mom brought me to Norrie School where a nice lady sat at a low table with me in a borrowed classroom. She wore her orange-tinted hair tight in a bun and a few tiny gold necklaces around her brown turtleneck. Her polyester pants had a riot of white, tan, and brown circular outlines. I liked her brown eyes because she never rolled her eyes when I could not understand her. The shiny baubles on her wrists fascinated me. Once she realized this, she removed them to her purse and gently said, “Look at me.”

I took my earmolds out.

“Do they hurt?”

I nodded.

She examined them and pulled out a nail file from her purse. She filed down the tubular edges of my molds and wiped them clean with a spray of rubbing alcohol.

The molds didn’t hurt as much.

I decided I liked Mrs. Gates.

Beyond this, I do not remember anything more, except that I learned to speak. I started to connect the odd language of disjointed lips and half-heard words, and tried to translate them the best I could. I sat in the front row of each class I attended and focused on the teacher’s face.

I tagged along with our siblings on their many adventures. I rarely spoke. I was too busy watching their faces and mimicking their movements.

I didn’t understand how the older they became, the less they wanted me around.

That is when you saved me. True story.

UP AND DOWN the street the oak trees grew their green hair until their heads swelled, casting wide bouffant shadows in their wake. When we pedaled our bikes hard up the sidewalk to our house, the shade cooled our sweat. Sometimes we left our bikes against the trees when we had to run into the house for a quick bathroom stop or a sip of lemonade, made from a powdery mix, before we ran back outside for a ride somewhere.

Sometimes we zipped past Mrs. Southern’s house and her dog that always barked like mad from behind the fence, turning the corner left around Mr. Zakofsky’s house where he hosed rows of his vegetables every morning, and waving hello at Billy, the fat and scruffy mechanic who usually stood inside the shade of his garage to smoke when he wasn’t fixing cars. We knew the faces of each neighbor who lived in these houses along the way to town. We had watched them talk with Mom many times. Sometimes they simply wanted to unload a bag full of zucchinis, and sometimes she would turn around and give them away to an older woman who lived on the other side of town.

No one liked Mrs. Harter. We never knew how old she was, but her face had the most wrinkles of anyone we saw. She had a longish wattle under her chin. We called her the Turkey Lady when no one was around. She always wore a thin sweater even during summer. We never understood how it was possible for anyone to feel cold in the hot months. Our house never had air conditioning; we left the windows wide open. We never knew the full details of Mrs. Harter’s story, but she did not have a husband, or rather, she had a husband who died in World War II. When Mom handed over a big grocery bag of zucchinis, she smiled at each one of us. We didn’t like her because there was something fake about her. We couldn’t quite put our finger on what it was, but we never talked about it. Once she was out of sight, we never thought about her. Mom said that helping Mrs. Harter was her way of being a better Christian and we should do the same thing for others too.

We didn’t quite grasp that America had fought many wars. We’d overheard names like Germany, Korea, and Vietnam, but they had nothing to do with us. These names were something like bad words among some of the men who sat on the porch over at Mr. Quinn’s house two blocks over. If the winds were strong enough, we could catch a whiff of their cigar smoke from half a block away. In the twilight their faces melted into the shadows of their voices, which turned quieter until they whispered themselves into oblivion.

By then we’d be tired from trying to capture fireflies with our jars and lying on the big baseball field where we looked straight up at the stars. We pointed out this or that star, but we’d never studied astronomy. So many stars were diamonds waiting to fall and turn into snow in the darkness of winter. Summer was just a way of storing them, much like how in the autumn the squirrels scattered about our street, snatching up one acorn after another.

When we pedaled to town, it was to pick out a scoop of ice cream at Stella’s Palace. It had some other name, but someone jokingly called it her palace from the way she mispronounced the word “parlor.” The name fit because of how she ruled the place. You knew her royal presence once you entered. She always wore a yellow top with a white collar, and she had three people, usually college students, wearing the same outfit. She made sure she knew all of our names, and she always asked after our parents. She had a great smile. Once we were done eating, we hopped on our bikes and pedaled as fast as we could home.

These are the stories that our siblings like to tell each other at family reunions. It’s been years since I’ve gone back.

OUR HOUSE HAD only two bathrooms for us seven kids plus Mom and Dad. The small one had a tiny sink and a toilet. The large bathroom had pink walls and two columns of lights on either side of the wide mirror overlooking the sink counter. Some of us were small enough to hide underneath there when we played Hide and Seek; unlike anywhere else in the house, it was strangely empty except for a growing pile of magazines and newspapers on the left side. Dad collected these once a month and brought them downstairs where they were tossed into the furnace. Dad and Mom never liked to waste anything.

The large bathroom’s window overlooked the backyard where, one Saturday afternoon in June, we’d helped Dad build a shack out of scrap wood from a neighbor friend. We followed his instructions, holding the dull-colored two-by-fours, as he sawed and hammered in nails. We held up each wall as he stood atop a ladder and hammered a piece of scrap wood to hold the corners together. We held the flat A-frames upright as Dad measured the space between each. We unrolled tarpaper and banged them into plywood. We held together each piece of the roof and watched it ascend to its rightful place atop the new shack. We scrubbed specks of old paint off the tiny window panes and held it in place while Dad tapped at its four corners to ensure perfect alignment with the wall itself before nailing it. We carried the caulking gun and took turns squeezing the trigger along the gaps around the window. We filed down the top and bottom of an old door, its white paint caked with time, over and over until it could finally fit the doorframe. We screwed the hinges into place while Dad sipped a can of Pabst and watched us. We took turns opening the door and jumping up and down inside the dark space. Once we realized only four of us could fit there lying down, we argued over who would get to spend the first night. Dad had to mediate. You and I were too small, so we never got the honors. But you and I would learn to climb the big tree that stood behind the shack, leap onto the roof, watch the cars that went up and down our street, and jump off onto the grass.

EVERY DAY AFTER school, you sat on a stool where the bathroom mirror’s eight lights converged on your face as Vicky stood behind you. On the counter was a book filled with drawings that showed how a girl’s long hair could be braided and styled in so many ways, and Vicky was working her way through the entire book. At the start of each session she divided your hair and held down each section temporarily in a barrette, and followed the book’s instructions. Thirty minutes later you ran out of the bathroom into the kitchen and bobbed your head to show off your new style. You were three years younger than me. Mom oohed and ahhed. It seemed that your hairstyle changed every day. I was jealous of your hair and the attention it got.

You didn’t know how blessed you had been with such silky hair. It glowed in the sun, and the white of your scalp showed through where your hair was parted. You played with your braids, and sometimes you loosened them. You whirled around on the grass, your hair petal-like from the unbraiding, until your head turned into a flower whizzing on the wind. I spun around too and ran after you. When we fell giggling from so much dizziness, dandelion whiskers rocketed off around us and caught the breeze. We watched them drift away before we got up again and spun again. Vicky was usually annoyed when you entered the house, your hair undone, but not for long. There was always something new to try from the book of braids.

When it rained outside, you and I played tic-tac-toe and hangman on scrap paper. Then you and I played card games on the living room floor. You and I made up rules and changed them all the time. You and I won and lost, and played again. You and I played double solitaire, gin rummy, and old maid.

Then you began to watch our siblings come and go out of our house. I had to wave for your attention and ask where they said they were going.

What was happening to the story of us?

EVERY SATURDAY WE sat in front of the television and watched Minnie Pearl, Lawrence Welk, and Carol Burnett. We took turns in the tub, where we had our weekly baths. We felt like newborns in our pajamas, which had been washed earlier that day. The TV filled our living room with a radiance of color and tinny applause coming from its one speaker. You nudged me with a tap on my arm when you caught puzzlement on my face during Hee Haw. I turned to you, and you repeated some of the things the folksy comedians had said. I didn’t laugh and you didn’t either, probably because you hadn’t grasped their humor, but you repeated them to the best of your ability anyway. When Lawrence Welk came on, we linked hands and danced around the room whenever we saw people on the ballroom floor. But I rarely needed help with Carol Burnett. She was so easy to lipread, and her facial expressions and body language told the whole story. Whatever words she said were quite beside the point.

Our house had a dining room, but we rarely ate there. All nine of us ate around a big table in the kitchen. I sat by the largest window where the light from outside fell on their faces for easier lipreading. Our words turned into a cacophony of conversation that dove around each other like sparrows. Laughter would suddenly puncture my eardrums, but I never caught what had been so funny. Sometimes they would be laughing so hard that they cried. I was the only one who never laughed nor said a word, the only paragon of silence who wanted to scream, “I’m here!”

But you caught my eye. You pointed with your eyes to this or that sibling, and you mouthed a summary of what they’d just said. I turned to them and grasped more of the words on their lips. When they shifted gears, I turned to you.

You pointed again to someone else around the table, and mouthed what they said.

Each time when I was lost at the table, I turned to you.

I didn’t understand that you needed me because you were lost too. You were then too young to participate in the banter. I was simply grateful.

I was your number six, and you were my number seven.

Do you remember that? I still do.

DAD WORKED LONG hours at the last factory in town. He was responsible for mixing recipes of certain color dyes for the thick burlap fabric later turned into stiff backpacks and tents. This was years before it went out of business after a new breed of nylon was developed elsewhere into something stronger, thinner, lighter, and completely waterproof. We rarely saw him. We knew his presence when he came home late. He rarely spoke, and when he did, we listened. He told us terse stories about the times he used to live on a farm north of the town where we lived. He took us there once and introduced us to the new owners who had taken over the place and made it a hobby farm. They seemed amazed that he had so many kids. We didn’t think we were a big deal. We never questioned how we came to be so many. We were named after aunts and uncles, but we were too busy to hang around with them when they drove long distances from California and Nebraska and Illinois to visit with us.

After we watched from the front stoop of our house the July Fourth fireworks that exploded high above the community college parking lot a few miles away, Dad opened a big brown box. He had bought fourteen boxes of sparklers, and we would get a pair of boxes each. We took turns running up and down the street with the sharp gray sparklers flickering in our faces, calling out to our parents to look at us, look at me, look at this! It seemed that even with the mosquitoes trying to nibble at our necks and arms and legs, nothing else mattered. The sparks of white burned slashes across the front of our eyes, and it seemed to take a good fifteen minutes before the burned images would fade from the inside of our eyelids.

I watched you write my name in the air. Your signature scorched my eyes.

I wrote your name in the air. It felt like magic.

We laughed.

It was the first pure family joke that I got without needing a backstory.

Our faces shimmered as we waved the sparklers in front of us. We kept writing each other’s names.

We took turns for Dad to light us a new one.

Mom leaned toward him, and they whispered to each other on the stoop.

It seemed the night would never end, but when the last sparkler went out, the bats careened out of nowhere. We screamed at the bats fluttering and making X’s under the streetlamps while moths flocked, trying every which way to break through to the hot glass bulbs. We didn’t know that some of them would lose their wings and die. We couldn’t stop watching their madness, but once the bugs multiplied around us, we had to go inside.

The true stories I remember of us are so far and few.

THEN CAME A new girl who moved into a house three blocks away. You were ten years old, and I was thirteen. My body had begun to change.

Her house on Spruce Street, having been long vacant, suddenly looked different with white paint with yellow trim and new double-paned windows. A new one-car garage was built with its driveway smoothly paved in pitch black. Her father wore baggy Carhartt pants, and it seemed that a cigarette was never far from his mouth. I watched him sit on his riding mower, going up and down each row on his ridiculously small lawn. I never understood why he couldn’t use a regular lawn mower. But I didn’t know that he had taken a new job at the burlap factory. He was an Ironwood boy who had pined to return ever since he left for the Army and met a woman who wanted to stay on in her big shot city. When he lost his job of ten years there, he called up his old buddies and snagged a job at the factory.

Then I saw her mother struggling to get out of the car. She was portly and wide-assed in a muumuu that hung like curtains around her body, and she wore bright orange ball earrings. She waved hello at us when I walked past with you. We were on our way to play at Norrie School.

She said, “Why hello there! Are you from around here?”

You nodded, so I nodded.

“I know someone you should meet.” She turned and yelled at a second-floor window above the driveway. “Ava! Come on outside.”

That was the first time you saw the girl who would change your life.

As Ava walked toward you, she wore her long hair with curls only at the end and her nails were painted a pearly white. Her thin-knitted top had a white collar. She looked poised with pearl earrings and designer jeans. As she came closer, she rolled her eyes at you, as if to say that her mother was so embarrassing. Even though she was ten years old, she seemed much older.

You told her your name and pointed to me. “She’s my sister. She’s deaf.”

“Hi, Ava,” I said. “Nice to meet you.”

She only giggled.

I looked around. Nothing was different. I didn’t see anything that could be making a funny sound. I looked up at the sky. Maybe a bird was making a weird noise. Nothing. It took me a long time before I realized she had found the sound of my nasal voice funny.

By then I had come to hate Ava McKeen.

BY THEN THERE weren’t a we anymore. We as a single organism had splintered once Patty followed Vicky by leaving Norrie for Ironwood Catholic High School on the other side of town. It seemed our siblings were disappearing one by one, and suddenly you and I were the only Foresters left at Norrie.

I felt more isolated when my classmates began to divide into cliques. Even though I was told I was an excellent lipreader, I was never sure what the girls by the brick wall talked about. I sensed they were talking about boys. Or music. Or movie stars. They gave me sneers of what-you-lookin’-at every so often.

I looked at myself in the mirror every day. My face was riddled with pimples. Each pimple I squeezed felt like a bullet hole. I found the presence of hair growing right out of my own body a bit creepy. I hadn’t quite understood the sex education classes because they showed slides with no text. I couldn’t lipread Mr. Whitman in the dark, but I could hear the titters when he showed simple drawings on the slide and continued in his dreary voice. I did not see a vagina or penis on the screen. Just general outlines of the male and female bodies.

I didn’t notice the changes in you at first.

You began to spend more and more time at Ava’s house, but you always came home right before dinner. You were learning to wear makeup.

Mom noticed. “You’re not Cleopatra. Take that stuff off right now.”

You rolled your eyes at her before you went into the bathroom.

Then one day you showed up in a blouse that was almost too tight. I saw the beginning of your breasts, and the soft clefts in your shoulders from your bra straps.

Mom said, “That’s way too tight. Change into something else.”

When you came back, dinner had already started. I scooped out the mashed potatoes and a medley of beans onto your plate, and waited for you to say something about the conversations whizzing about our heads.

But you said, “Thank you,” and you turned your attention to the banter.

When they erupted into laughter, I turned to you.

You were laughing, too, but you ignored the puzzlement on my face.

I said, “What?”

You rolled your eyes at me and said, “Later.”

I was furious. You had turned out to be just like everyone else in our family.

Then someone cracked a joke. I never knew what was so funny, but I watched you laugh. You weren’t laughing like before. Your laugh was strangely hollow, full of grown-up fakery. The carefree laughs you had shared with me were gone.

That was a story I wasn’t prepared to read.

YOU AND MOM fought long and hard about Ava’s influence, but the damage was already done. Even Dad forbade you from doing another sleepover at her house.

You permed your beautiful hair without warning anyone, and it so damaged your hair that you couldn’t wear it long like before.

I straightened my posture and clipped my body hearing aids away from my breasts to my belt.

You took up smoking on the sly.

Library books became my best friends in high school; they were easy to lipread.

You hung out with teenage boys over at the McDonald’s by the highway.

I graduated from high school and left for college out of state. Mom and Dad were upset that I’d chosen a deaf college, but I didn’t care.

You graduated from high school.

I didn’t show up for your commencement. I had become a broke college student, but I had learned that I wasn’t the only deaf orphan abandoned by a hearing family. I became fluent in the mother tongue of my chosen family, who signed. Mom and Dad turned cold once they saw how much light I emanated from within. I was worthy. I had friends who loved me as I was. I was happy being Deaf.

You dropped out of community college and took one babysitting job after another until you met Bob, a divorced mechanic, in a bar on Aurora Street.

With only one look at him, I knew you were fucked. He oozed braggadocio about how much money he was making all the time, and yet he had nothing to show for it.

But I didn’t say anything. I knew you’d just roll your eyes at me and give that fake laugh.

You married him.

I didn’t show up at your wedding. I didn’t want to see Ava as your maid of honor. I don’t think Mom and Dad did either.

You had two kids with Bob.

I didn’t show up for their baptisms either.

You eventually found out that he had been cheating on you all these years.

When Dave proposed to me, we did not tell our hearing families about the wedding. We wanted our special day to be Sign-only. We moved to a suburb in northern Virginia where we raised four hearing kids. I got along well with my co-workers and worked my way up as an accountant at the Pentagon. I managed to write enough stories on the side for a collection that eventually got published, but no one in our family bought a copy. That hurt.

You divorced Bob, but it took you a court order or two to make him pay alimony. You became a full-time beautician and a part-time babysitter. Your older boy had become a chronic troublemaker; you had to pay bail for him twice. Your younger girl was quiet like me. I knew that one day she would blossom like me.

I didn’t return to Ironwood until Dad died. Everyone in our family and others at the funeral remarked on how sharp I looked in my blouse and skirt. I said, “Thank you,” but I didn’t know what else to say for a return compliment. They had grown fat. I also hadn’t thought to ask for an ASL interpreter until it was too late; Ironwood didn’t have any Deaf people. I had been overwhelmed with arranging the logistics of flying my family in for the funeral. As my kids sat and listened to the service, I interpreted for Dave discreetly in the pew while trying to lipread the new priest, who clearly didn’t know Dad at all. My interpreting was crappy, but Dave’s eyes were full of gratefulness.

Afterward, I caught the look of envy in your eyes when you surveyed the clothes on my kids. You asked about my salary, and my answer shocked you. I was making far more money than any of our siblings.

As I watched how well my kids behaved with everyone and signed with me, I felt pleased to see that they’d learned from my example. You exclaimed at their politeness.

I beamed. “Thanks. Say, whatever happened to Ava?”

You rolled your eyes. “Don’t ask. We’re not friends anymore.”

This time you didn’t laugh.

I wanted to say, “Serves you right,” but I didn’t. You averted your eyes when I gave you a look instead that shouted what only Deaf people growing up alone in hearing families often dream of saying out loud to their families but share only with each other: You hearing people always think of us Deaf people as nothing. Oh, no no no. No more of that crap. We’re equals worthy of respect!

I’d like to change the ending of our story, but I won’t. You can write the rest of the story on your own.

Stella, Gone

ONE MORNING ON West Lime Street, at the southernmost end of Ironwood’s city limits nearest the border of Michigan and Wisconsin, Stella Draper woke up and realized she was suddenly thirty-three years old. This being the alleged age that Jesus Christ died, she took her father’s antique Colt .45 and sat in front of the eleven jars of skin creams that she’d bought from Gibson’s Pamida and McLellan’s. She arranged these potions carefully in front of her vanity mirror where she’d spend hours camouflaging the five moles on her face so they would never appear as bumps. She placed the gun’s muzzle on her tongue and pulled the trigger.

Of course, the Ironwood Daily Globe never reported on any of this; only that she’d died by her own hand. The date was June 3, 1977.

I WAS TEN years old when she died. I didn’t know it then but I was already a ghost. I had a body that said I was made of flesh, but I drifted through my days and nights. I was a balloon filled with the helium of fakery. I had a name, but it wasn’t really me. I was desperate to float away because all I saw was fake-smile pretenses. I hated the clothes Mom gave me to wear: skirts with frilly hems, blouses with pink and green stripes, and white corduroy vests. The syrupy warmth in Mom’s voice made me taste the bile rising in the back of my throat each time she said, “My, my, what a pret-ty girl you are.” She wanted to braid my hair, but I always ran off and let my hair grow untamed in the summer. Everyone called me a wild child, but I never saw myself as wild. I was just Kit.

I’VE OVERHEARD PEOPLE say that I’m trying to be a man, but that’s not even half the story. I like wearing men’s clothes. They hide the contours of my body. They’re also comfy. My chromosomes say I am XX, but my brain insists I have no gender. I don’t think of myself as female when I strip down to take a shower. I have pubic hair, but my vagina doesn’t define me. It’s only there to relieve my bladder pressure and the pent-up orgasms when I rub myself into a bliss that does not revolve the mating of sexual organs.

Every now and then somebody will say, “Hey, dyke.” I give them a look so mean and dirty that they back off. They don’t understand that I’m not a lesbian. What I am doesn’t have any label. Period! Why is that so hard to understand? I used to go out every Friday night to the Memorial Building for the fish fry, but some of these people eating at the tables gave me a look of disgust when I picked up my order. So I’ve learned how to deep-fry fish outside in the summer. Tastes much better when you do it yourself anyway.

I’ve thought about packing up my stuff and moving away to a city that’s bigger than Ironwood, but each time I do, an arrow of fear—how can anyone afford such expensive places? how can I find a decent-paying job with only a high school diploma to my name?—pierces my body.

When I ring up a sale for customers with license plates from California to Maine, I give them a smile. I envy their ability to travel anywhere. They don’t have to worry about money like I do. Because they’re from anywhere but here, we excuse their odd behaviors. They have the money, and we don’t. This is how small towns work.

IT WASN’T JUST her breathy smile that I remembered. Each time I entered Stella’s Palace, where she served scoops of sherbet and banana splits, I remembered her body more. Her thighs and her bosom filled out her yellow-and-white polyester pants and blouse. I could see the contoured outline of her bra pressing hard against her flesh. Her loop earrings were oversized. She laughed at our looks of amazement. As she pointed to her earrings, she said, “These? These are my hula hoops.” She shook her head for effect. We laughed. “Now, what do you guys want?”

As we gave her our orders, I gazed up at her gussied-up hair. It was an unnatural shade of black. It never occurred to me that a woman that young would want to dye her hair; I’d seen how a few older women at church would dye their over-permed curls a weak shade of brown. That Stella’s face had so much makeup never bothered me, but when I started to notice how tan and supple her forearms were, the paleness of her makeup made me wonder if her face was indeed ugly underneath.

WHEN SHE DIED, I hadn’t grasped the fact that it had been ten years since Ironwood had closed its last mine. The town had profited enormously from eight decades of intensive iron ore mining, especially during the World Wars and the Korean War, and then there weren’t enough ore left to extract from the land. Amidst its residents leaving by the thousands for jobs elsewhere, Ironwood had been in a state of constant grieving although no one ever called it that, but there was no other way to describe the scent of elegy lingering in the air. Even into the early 1980s, we all pretended that Ironwood was still alive—look! we even have three record stores within three blocks of each other—and—see? Aurora Street was always full with parked cars—but in the quiet nooks of our hearts, we knew the town was cloaked in a perpetual candlelight vigil.

And yet the moment Stella died was the first time she came truly alive. It was as if the people of Ironwood had finally noticed something quite outside the long funeral dirge they’d been participating in for a decade. It was as if they were opening their eyes for the first time and saw the sadness come out of the shadows of memory. I flitted among them, my ears keening on the snippets of anecdotes about her. Gradually, I pieced together her story.

Stella graduated with the Class of 1962 from Saint Ambrose High School. She attended Masses at Holy Trinity Church, which were two corners away from Stella’s Palace and directly across the street from the post office. Behind the post office was the Ironwood Depot, where people took trains southward to Green Bay and Milwaukee and Chicago, but not anymore because everyone had cars, and there was Greyhound too. Ironwood had three Catholic churches, and all within a five-block radius of each other on the edges of downtown. The dark chocolate brown façade of Holy Trinity struck me as being the most restrained even with their extraordinarily beautiful stained glass windows. I couldn’t imagine Stella dolled up for church!

SINCE THE EARLY 1940s, the women of Ironwood, many of whom were cursed with the ache for renewed romance in their lackluster lives, talked endlessly about the story of Stella’s parents.

Marty and Ellen had met as teenagers at the Luther L. Wright High School, but they didn’t connect romantically until he came back from having served the U.S. Navy while on the USS West Virginia