Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Fox Chapel Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

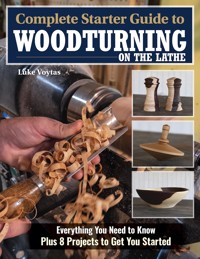

The ultimate, beginner-friendly woodturning guide! Approachable and simple, this resource will show you how to use a lathe and build your turning skills as you create functional and attractive woodturning projects. Featuring insightful opening sections on sourcing green wood, the anatomy of a lathe, food-safe finishes, tools, sharpening techniques, and more, Complete Starter Guide to Woodturning on the Lathe then presents eight illustrated projects to help you get comfortable using a lathe and hone your woodturning skills that also double as practical items for the kitchen and workshop, or make for great gifts to family and friends. From turning a honey dipper and bowl to a mallet, and keepsake box, each stunning design includes step-by-step instructions, full color photos, and materials lists to ensure success. Discover endless possibilities once you gain a foundation of basic turning skills on a lathe with this must-have woodworking guide!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 208

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedication

To Mom and Dad

© 2023 by Luke Voytas and Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc., 903 Square Street, Mount Joy, PA 17552.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holders.

Print ISBN 978-1-4971-0395-5ISBN: 978-1-6374-1241-1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023943286

Managing Editor: Gretchen Bacon

Acquisitions Editor: Kaylee J. Schofield

Editor: Joseph Borden

Designer: Joe Rasemas

Proofreader: Kurt Connelly

Indexer: Jay Kreider

To learn more about the other great books from Fox Chapel Publishing, or to find a retailer near you, call toll-free 800-457-9112 or visit us at www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

We are always looking for talented authors. To submit an idea, please send a brief inquiry to [email protected].

Because working with a lathe, carving tools, and other materials inherently includes the risk of injury and damage, this book cannot guarantee that creating the projects in this book is safe for everyone. For this reason, this book is sold without warranties or guarantees of any kind, expressed or implied, and the publisher and the author disclaim any liability for any injuries, losses, or damages caused in any way by the content of this book or the reader’s use of the tools needed to complete the projects presented here. The publisher and the author urge all readers to thoroughly review each project and to understand the use of all tools before beginning any project.

Introduction

If you’re interested in woodworking, woodturning is a great place to start! For experienced woodworkers, woodturning provides another fun skill that can elevate furniture, transform scraps into useful items, and be an endless source of amusement and exploration. Creating on the lathe has an immediacy that is one of its great strengths. With a piece of wood, a little knowledge, and a bit of time, you can create something unique. It’s an expression of your vision and aesthetic. You choose if it will be something beautiful, something functional, or just something that will be sure to impress your friends!

One of the best things about woodturning is how approachable it is to a wide group of people. The lathe doesn’t require a lot of previous knowledge to become proficient. A turner doesn’t have to be terribly strong or large or possess any particular physical gifts. All people, old and young, big and small, can have fun woodturning. It just requires the turner to be tuned in mentally and physically to the action of the tools and the lathe. The experience is immersive and it’s easy to enter a state of flow.

The process of woodworking is a conversation between the crafter and the wood. Each piece of wood has unique properties that it presents to the woodworker. The woodturner’s duty is to discover those features in the grain, color, and structure of the wood. It’s the history of the tree that we help to write through contributing our spirit and intention. Woodturning is a great way to tell the story of a tree, of nature, and of our own place in the world.

The lathe has several advantages for someone new to woodworking. One of the biggest is that it doesn’t require much equipment to get started making things. It’s not like building a cabinet or fine furniture, where you need access to a full shop of woodworking equipment. With just the lathe and a few sharp tools, you can transform a piece of wood into something beautiful—maybe useful, too. Few tools also means a limited expenditure of money to get started. Many small lathes are still capable of making a diverse group of objects, even larger items like bowls, so you don’t need a lot of space to begin. Used lathes and turning tools are also easy to find and are often of great quality and beautiful in their construction.

Another convenience is how easy it is to source material for woodturning. Not only can you pick things up from a local lumber supplier or online, but you can repurpose wood from your property or municipality. This can be a big plus when you’re learning and don’t want to destroy a piece of material you spent a fortune on! A lot of the wood I turn is turned “green.” It’s fresh cut with a high moisture content. For bowls and certain projects, this is ideal; for others, it’s necessary for the wood to be dried. In this book, I’ll note instances where you can take advantage of green wood.

Being able to source material locally, from trees taken down by the city, by arborists, by myself, and by friends or neighbors has allowed me to give it a second life. It’s also easy on the environment.

This book will be a guide down the shortest path toward becoming proficient on the lathe. I’ll lay out many of the best time-tested methods of woodturning in language that’s easy to understand, while recognizing that some readers may not have a lot of sophisticated equipment to get started. This will form a foundation on which to build your knowledge, but it’s not the only source. My students have had the most success when they pair reading about turning with watching turning in the form of videos or demonstration, working with a teacher, and most importantly, practicing! Just be judicious in the materials and guides you choose to learn from. There’s more than one route to your destination, and many differing opinions, so seek out sources you know to be reliable and experiment from there.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Getting Started

Anatomy of the Lathe

Woodturning Glossary

Woodturning Safety

Selecting Wood

Sourcing Wood

Hardwood vs. Softwood

Understanding Wood Grain

Working with Green Wood

Preparing Wood

Dried Lumber

Green Wood for Bowls

Laminating Wood

Securing Wood to the Lathe

Tools and Techniques

ABCs of Woodturning

Intro to Tools

Duplicating Forms and Patterns

Sharpening Demystified

Tools for Sharpening

Sharpening Techniques

Finishing

Food-Safe Finishes

Other Finishes

Milk Paints

Stains

Drying Turned Green Wood

Long-Term Wood Care

Projects

Wooden Mallet

Rolling Pin

Honey Dipper

No-Sand Wooden Top

Custom Handles

Salt and Pepper Shakers

Green Wood Bowl

Keepsake Box

About the Author

Getting Started

Anatomy of the Lathe

Woodturning lathes have been around for thousands of years. Although they’ve changed dramatically during that time, in principle they are rather simple machines. Their function is to rotate an object into a cutting tool.

You don’t need a costly lathe for it to be effective. You can still learn the essentials of woodturning and produce varied and beautiful objects with a simple, relatively inexpensive lathe. Benchtop lathes are a good place to start, and used lathes tend to be easy to come by.

While specific features may vary between lathes, the components depicted here are pretty much universal.

Wood lathes have some basic components that are universal. It’s important to get familiar with these basic parts of the machine as I will refer to them frequently throughout the text. This Jet lathe is in constant motion at the GoggleWorks Center for the Arts. It’s not the fanciest machine, but more than sufficient for diverse items, such as bowls or table legs. It’s produced thousands of projects, and it’s starting to show!

Woodturning Glossary

Banjo. Mounted to the lathe bed, the banjo can be moved in and out, slid right to left, and rotated to place the tool rest in the proper position for safe turning. A lever at the front allows the banjo to be locked in place. The tool rest slides into a hole on the top of the banjo where it can be rotated, moved up and down and locked in position with a second lever.

Bead. A rounded surface cut into a piece of wood. Here, it’s used loosely to describe any convex, rounded forms.

Bevel. The surface of the tool that is sharpened to produce a cutting edge.

Burr. A burr is the fine metal remnants left on the opposite side of a sharpened edge. Finer stones and abrasives leave smaller burrs and superior cutting edges for most tools.

Chuck. A tool used to hold a workpiece. Most commonly referring to a 4-jaw chuck, it uses a key to synchronously tighten the jaws around the work.

Cove. A concave, rounded form cut into the wood.

Drive center. This tapered steel rod fits into the lathe’s spindle and is held in place with pressure from the tailstock. It has teeth or prongs on one end to provide purchase in the wood to rotate the workpiece.

End grain. The surface of the wood where it is cut across the fibers.

Faceplate. A round metal disc with holes in it that is used to secure work to the headstock, especially for bowls and other heavy turnings. Screws are driven through the holes into the work while, opposite the work, a threaded hole allows the plate to be twisted onto the spindle. Used with or without the tailstock.

Figure. The wood’s particular visual characteristics that make it unique. Figure can be curly, rippled, quarter-sawn, quilted, etc.

Flute. The center groove cut along the length of a gouge’s metal shaft or shank.

Gouge. Edged tools with a curved, hollow profile allowing the tool to be used without engaging the outer edges of the cutting surface.

Grain. The orientation of the wood’s fibers as it relates to the growth of the tree.

Handwheel. At the rear of the tailstock, a round crank that can be rotated to move the live center forward or backward. At the headstock, a spindle-mounted wheel that can be rotated to aid in threading chucks and faceplates onto the lathe.

Headstock. This part of the lathe sits on top of the bed to the left of the operator and contains the spindle to drive the workpiece. Often, the lathe’s motor and controls are contained within the headstock, too.

Lathe bed. The horizontal surface consisting of two rails on which the headstock, banjo, and tailstock are mounted.

Live center. A freely rotating pin or cone, located opposite the spindle that drives the workpiece, that supports the work, especially in spindle turning. The live center is mounted in the tailstock.

Long grain. Orientation of the wood’s fibers when they run the length of the wood.

Mandrel. A tool, often shop-made, which allows for a partially completed workpiece to be mounted to the lathe without damaging the wood.

Pith. The very center of the tree from which growth rings radiate outward.

Rip. A cut which follows the grain of the wood lengthwise, following the vertical growth of the tree.

Shoulder. The sides of the gouge to the left and right of the central point.

Spindle. The spindle is rotated by the motor to spin the workpiece. In woodturning, the spindle is hollow to allow centers to be pressed inside and driven out from the opposite side. The exterior ends of the spindle are threaded to allow faceplates, chucks, and other fixtures to be attached.

Swing. The maximum diameter workpiece that can be turned on the lathe. A lathe with a 16" (40.6cm) swing would have 8" (20.3cm) between the bed and the spindle.

Tailstock. Mounted on the right side of the lathe bed, the tailstock can be moved forward and backward to provide support to the workpiece using a live center or for mounting a fixture or chuck for other applications.

Tear out. When wood fibers split apart from a tool, pulling fibers apart instead of compressing them, resulting in a rough work surface.

Wing. The area of the bevel that flows back from the central cutting point on a gouge.

Woodturning Safety

A friend of mine taught woodturning in a high school shop class. Lodged in the ceiling was a skew chisel a zesty student launched from the lathe after getting a dangerous catch. It remained there for many years as a reminder to the youths of that small town in western NY that everybody needs to have at least a basic understanding of the process, risks, and forces at play before they engage in a task.

When you enter the shop, come in prepared to work, with proper attire and the right mindset. Woodturning is messy, and to do it properly, you can’t be restricted by the fear of damaging your clothes because then you can’t engage with the tools and materials properly. Clothes shouldn’t be too baggy, or they can get caught in the lathe. Long sleeves should be tight-fitting or rolled up. Although gloves may seem like a good idea, they can be especially dangerous. It’s easy to keep track of where your fingers are in relation to what you’re doing, but not with gloves. They can easily get caught between the lathe and the tool rest. Remove any loose, dangling jewelry like bracelets and necklaces, and tie back long hair.

Shoes need to be closed-toed. Boots or steel-toed footwear are great options but aren’t strictly necessary. Should your workpiece or a tool fall, you can count on gravity to direct them toward your feet. Turning is a dynamic process, one in which you need to have good footing and the ability to move about. Choose something practical and sturdy.

Always wear safety glasses when operating power tools.

Woodturning is dusty. Use a tight-fitting respirator or dust mask, especially when sanding.

Whenever power tools are being used, wear eye protection. Safety glasses are cheap and come in a wide variety to fit even the most misshapen of heads. Buy extra so you’re never at a loss for a pair. Brightly colored ones will save you time searching, as will a handy eyeglass string.

A face shield is required when turning projects that will send wood chips toward your face.

For woodturning, you also need a face shield. These don’t have to be expensive, but they should be comfortable. For most turning tasks, safety glasses will suffice. For bowl turning, you need a face shield, as the chips and pieces of bark will be flying right at your face.

It’s easy to overlook breathing protection, but a lot of woodturning is dusty. Airborne particulates are generated not only when you’re sanding or making woodchips fly, but also when you’re sharpening. A dust mask is okay, but a nice, tight-fitting respirator is a huge upgrade. You can find these at hardware stores, but I recommend looking online and reading some reviews. Find one that is comfortable because you will be wearing it for long stretches of time. Most have dedicated sizes and you should find one to match your head.

When you are turning, always give your workpiece a spin before you switch on the lathe. This will ensure everything is tightened down properly and that your workpiece won’t be striking anything, potentially coming loose or sustaining damage. Always remove the tool rest before sanding. Sandpaper can get grabby, and in no time, you’ll be stuck between the rest and the spinning workpiece.

Above all, keep safety constantly in mind. Take your time and be thoughtful when you’re turning. Inspect the lathe and your attire before you get started and you’ll be safe and successful!

Selecting Wood

Sourcing Wood

Finding wood for woodturning can be very easy. Wood can be sourced from local lumber suppliers, craft stores, and online, but even a small piece of scrap wood or a trimming from a tree can be transformed on the lathe into a beautiful and functional object. Where I live in rural Pennsylvania, the forests are rich and diverse. As a result, there are lots of small businesses where I can source local, high-quality lumber at a great price. Additionally, being handy with a chainsaw means that I’m able to make use of trees that fall in storms or those that must be removed from friends’ properties when they become a nuisance or safety concern. Even with my terrible personality, I have enough friends to keep me busy with tree work, leaving me with a constant supply of fresh wood! This material is especially useful for bowls, but it can also be dried out for spindle turning. When you select something to turn on the lathe, there are a few things to consider, which we’ll discuss in the following sections.

Hardwood vs. Softwood

Most woodturning, and all the projects in this book, is done with hardwoods. Many hardwoods come from deciduous trees and have a few of characteristics that make them superior for woodturning when compared to softwoods like pine, fir, and spruce. Softwoods tend to be more readily available commercially because they are used for construction. Dimensional lumber like the 2x4s you would use to frame a house and similar material are sawn from softwoods. There are several characteristics that make them impractical for woodturning.

Here, you can see the broad growth rings in a softwood log. These make softwoods tricky to turn on a lathe.

One of the reasons softwoods are used for construction is that they grow fast. Much of this wood is sawn from trees that are just a few years old. This means the supply is renewed quickly, but because it grows so fast, the annual growth rings are broad. As the wood tends to split along these lines, it makes achieving a nice finish on the lathe more challenging.

Hardwoods grow slower than softwoods, giving them tight grain patterns as pictured here.

Consider the shape of many of these trees. Conical trees have branches that radiate around the trunk at regular intervals, like a Christmas tree. It’s here, where branches enter the trunk, that knots form. These are very hard and create voids and irregular grain that isn’t ideal for woodturning. Softwoods are used for some turnings, especially when the wood is painted, such as in stair balusters. Turners using softwoods are careful to select wood that has grown slowly and has tight grain.

Hardwoods usually grow slower than softwoods. The grain tends to be more consistent and contains fewer defects, making it easier and more predictable when it’s turned. As the name suggests, hardwoods are usually harder and more durable than softwoods, making them ideal for items that will get handled and used a lot. Hardwoods are less likely to dent and will be stronger when used in furniture applications.

When selecting wood for turning, there are several things to avoid. The first is knots. Knots are extremely hard and will dull your tools rapidly. Where knots are present, the wood of the larger limb is forced to grow around the knot, which creates irregular and unpredictable grain. Making clean cuts that are free of tear out in these areas won’t be possible.

Understanding Wood Grain

Here, you can see how the wood fibers are disturbed by the knot, then resume their original directional flow once past it.

Wood grain reflects how the tree has developed throughout its life. Grain follows the upward growth of the tree, flowing up the trunk and through the branches. Wood is a collection of fibrous, hollow strings of cellulose that are tied together to form the structure of the tree. These hollow strands form a highway to transport water and nutrients from the ground to the leaves for photosynthesis.

When a branch forms in a tree, these fibers are forced to move around the obstruction before returning to their original orientation in the wood. It’s like if you hold a paintbrush and press your finger down into the bristles. The bristles spread around your finger. If the bristles behaved like a tree, they would flow around the disturbance and merge back together.

When you run your hand across the bristles of a brush, it is akin to how fibers are pulled apart when using a tool to work wood with irregular grain patterns.

Where this occurs, the wood becomes less predictable for turning. At times, as you’re working the tool across the wood, it may be compressing fibers or pulling the fibers apart. You can imagine this when you take the brush and sweep your hand down and across the bristles. The fibers are pulled apart, and this is where we encounter tear out. This will produce a surface which will require more sanding. It can also affect the strength of the piece, as a turning with fibers running continuously from start to finish will be stronger than one in which the lumber “runs out” into space. You may also have this runout effect if the tree was not straight or the board or workpiece was taken from a branch.

Irregular grain in wood can be the source of great beauty and great frustration. Curly figure is an example of unusual grain that’s pretty but tricky for the turner. When light hits curly wood, it tends to shimmer. It’s here that the grain is wavy instead of straight. This is the result of wood that is compressed, such as in a branch where the wood is not just growing upward but outward and supporting additional weight. Although the wood is pretty, it’s going to be harder to cut and get a clean finish.

When buying wood, try to follow the path of the grain. In wood that’s planed, you can generally see the way the tree has grown. Select boards and pieces where this growth appears to be continuous from start to finish rather than wandering off to the sides. Look out for boards that are warped or twisted. This usually indicates tension in the wood, which may portend difficult grain. Sometimes this wood will even warp after turning because, as you remove material that’s held the wood in equilibrium, you might expose new sources of tension.

Working with Green Wood

As George Nakashima, the renowned furniture maker, said in his beautiful book The Soul of a Tree:

“When trees mature, it is fair and moral that they are cut for man’s use, as they would soon decay and return to the earth. Trees have a yearning to live again, perhaps to provide the beauty, strength, and utility to serve man, even to become an object of great artistic worth.”

Creating something from a tree is a celebration of that tree’s life. Each piece of wood is a representation of the tree and its lived experience. The wood reflects that life, and in the grain, we can see times of abundance when water and sun were plentiful and times of crisis when drought or disease caused the tree to muster its resources and fight for its life.

The Decline of a Tree

A short distance from my shop, a black birch tree has died. Moisture has been getting trapped on the uphill side of the tree, and because the canopy is so dense, it doesn’t dry out and rot has set in. The tree will be taken down to be turned into bowls.

It’s not necessary to harvest a healthy tree to find great wood for woodturning, but when a tree has matured and would otherwise return to the earth to rot, it might as well find a second life as a turned object. Sometimes, you can improve the health of a forest by harvesting some trees. This can allow more sun to reach desirable trees and plants and improve the quality of the forests for plants and animals. When forests are comprised of a small number of species, this can also be disastrous when disease strikes. Many forests have been devastated by the Emerald Ash Borer and Gypsy Moth. In some areas, entire wooded patches have died and what was once forest is now a matted mess of aggressive invasive species that do little to support a healthy ecosystem. Proper forest management and selective cutting could have made these woodland patches more resistant to these plagues by allowing a more diverse selection of trees to thrive.

Working with green wood is in many ways a celebration of an individual tree and our connection to nature. We can select wood that really reflects the personality and intentions of the tree and, through turning, have a conversation with that individual. With care, we can help highlight those traits that make the individual tree and the collective forest unique.

Commercially available wood is harvested from the forest from stable, predictably consistent trees. Foresters are experts in identifying these trees and selecting the right ones for loggers to harvest and send to the mill. To ensure the health of the tree, they are usually felled before peak maturity and from the best stock. As a turner, you can make use of more irregular trees and pieces and in the process, find some spectacular expressions of nature’s will.

When sourcing wood straight from the tree, seek out areas that are free of branches. Trees that grow in open spaces like yards tend to have more. That’s because the leaves branch outward to find sunlight and aren’t forced instead to travel skyward to reach above competing trees for sunlight. Trees from the forest have straighter grain and contain fewer defects. Still, a tree that is harvested from an open space will have lots of useable pieces if you know where to look.

Bowl turning is the most common way to utilize green wood on the lathe. Bowls that are turned from green wood warp, but that isn’t necessarily a drawback; for some, it’s a point of interest. For those who want to avoid a slightly oblong bowl, green wood can be twice turned to ensure it stays round. I describe this process in a later chapter.