Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

ferroequinologist (noun) Someone who studies the 'Iron Horse' (i.e. trains and locomotives). From the Latin ferrus 'iron' and equine 'horse' + -logist As the British steam era drew to a close, a young Keith Widdowson set out to travel on as many steam-hauled trains as possible – documenting each journey in his notebooks. In Confessions of a Steam Age Ferroequinologist, he cracks these books open and blows off the dust. His self-imposed mission, that of riding behind as many Iron Horses as possible prior to their premature annihilation, led to hours of nocturnal travels, extended periods of inactivity in station waiting rooms, missed connections and fatigue. However, any downsides of his quest were compensated by the camaraderie found amongst a group of like-minded colleagues who congregated on such trains. This is a book that no self-respecting ferroequinologist should be without.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 294

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Every effort has been made to source and contact copyright holders of illustrated material. In case of any omission, please contact the author via the publishers.

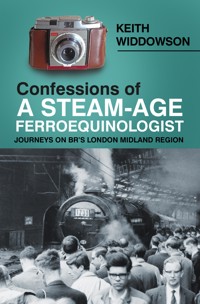

Cover illustrations:Front: A crowded scene at Liverpool Lime Street on Saturday, 4 June 1966 as Stockport-allocated Brit 70004 William Shakespeare prepares to take the LCGB Fellsman rail tour forward the 135 miles to Scotland. Back: Haulage bashers congregate at Warrington Bank Quay; a ticket offered to the guard after leaving Wigan.

First published 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, gl50 3qb

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Keith Widdowson, 2019

The right of Keith Widdowson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9345 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

About the Author

Introduction

1 In the Beginning

2 Voyage of Discovery: 1964

3 The Gone Completely Railway: 1965–66

4 The Electric Effect: 1966

5 Super Summer Saturdays: 1966

6 The 109-Hour Marathon: 1966

7 Mancunian Meanderings: 1966–67

8 The BRIT Awards: 1966–67

9 The Preston Portions: 1966–67

10 Steam’s Last Hurrah on the WCML: 1967

11 Sixty-Eight in Sixty-Eight: 1968

An Afterthought

Sources

Acknowledgements

Glossary of Terms

Appendix

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Keith Widdowson was born to his pharmacist father and secretarial mother during the calamitous winter of 1947 at St Mary Cray, Kent – attending the nearby schools of Poverest and Charterhouse. He joined British Railways in June 1962 as an enquiry clerk at the Waterloo telephone bureau – ‘because his mother had noted his obsession with collecting timetables’.

Thus began a forty-five-year career within various train planning departments throughout BR, the bulk of which was at Waterloo but also included locations at Cannon Street, Wimbledon, Crewe, Euston, Blackfriars, Paddington and finally Croydon – specialising in dealing with train-crew arrangements. After spending several years during the 1970s and ’80s in Cheshire, London and Sittingbourne, he returned to his roots in 1985 and there he finally met the steadying influence in his life, Joan, with whom he had a daughter, Victoria, now a primary school teacher. In addition to membership of the local residents’ association (St Pauls Cray), the Sittingbourne & Kemsley Light Railway and the U3A organisation, he keeps busy writing articles for railway magazines and gardening.

INTRODUCTION

Welcome to the fifth tome on my steam-chasing years between 1964 and 1968. Having exhausted my memories of steam in Europe, Southern England, Yorkshire and Scotland I have turned my attention to where steam in Britain died – the London Midland Region. By default it has become the largest publication of them all, influenced probably as being, after October 1967, the only place to be.

Perhaps using the irrational logic that ‘there will always be steam on LMR metals’, I had initially, excepting a brief Leicester-based foray in the August of 1964, concentrated on other regions during the formative years of my railway travels – the only LMR-orientated steam-train travels during 1965 were afternoon trips out of Marylebone and overnights to Scotland.

The majority of this book therefore depicts my visits to the LMR from the March of 1966 until the end. My self-imposed mission was to travel behind as many different steam locomotives as feasible and as the months went by and the steam passenger services became fewer, the waits for them – the remaining ones being confined to the night hours – became lengthier.

Here then is a travelogue of those expeditions undertaken during my teenage years. Along with like-minded friends, we led a carefree existence untroubled by world events. Yet to be burdened with mortgages, relationships and career prospects, we, using the generic overview, trainspotters, were able to roam the railway network in a frenzied pursuit of the centrepiece of our hobby – the steam locomotive.

Please join me on my quest: the successes, the disappointments, the scenarios I encountered and above all the realisation that history was being enacted, i.e. one of the last vestiges of the Industrial Revolution, the Iron Horse, was being extinguished.

1

IN THE BEGINNING

My parents met at a Somerset holiday camp just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War. Having qualified as a pharmacist, Dad was in the Medical Corps (behind the lines) at Dunkirk when, in 1940, the historic retreat was ordered by the government. After his inevitable capture by the Germans he endured a five-day train journey across Europe, becoming a POW in a camp in Austria before, in 1945, being liberated. Returning home, my parents married and settled in Kent – just a stone’s throw from the railway line at St Mary Cray. Born at home in the calamitous winter of 1947 (the midwife couldn’t get through because of the snow – Grandma having to deliver me!) I was to gain a brother four and a half years later.

The road in which we lived was initially just a cul-de-sac, at the end of which was an extensive orchard. During the early 1950s, in line with a great many other areas in the Home Counties, the orchard was cleared and an estate was built to house Londoners whose homes had been damaged by the war or were in sub-standard accommodation. As an integral part of the development, a church, shops, dentist, doctor, public house and a school were all built.

Directly opposite my house, however, because the ground was unable to sustain house construction, a wooded area was left untouched – and still is to this day. This parallels the London-bound railway line west of St Mary Cray station and, although it was our playground, it was only after the acquisition of a dog, whose predilection was to race against the passing trains, that I took any notice of the railway itself. Unlike many railway authors who commence a book detailing their earliest memories of what they spotted, even though the ideal environment presented itself I retrospectively regret failing to document anything passing along the former London & Chatham Main Line.

Attending the aforementioned primary school, a lack of common sense/inattention led me to fail the eleven-plus and although it seemed I was destined to attend the nearest secondary modern just a mile away, my parents, because of its reputation re poor discipline, etc., registered me to one more than 3 miles away – south of Orpington.

Although, after gaining my Cycling Proficiency badge – a prerequisite insisted upon by the school – during the summer I used my bicycle, the bulk of my journeys were made using London Transport buses. They weren’t as frequent back then as nowadays and it was necessary to purchase a local timetable. I became proficient, fascinated even, by it. So much so that, having purchased adjacent area issues, my brother and I embarked on days out exploiting the myriad of bus routes available using the Red (or Green) Rover tickets.1 Available on weekends only at 2s 6d (12½p), what a bargain they were – inevitably leading to Ian Allan books being purchased and serious spotting being undertaken. All the above was funded from my job(s) delivering papers. I had a morning round from the local newsagent and a Saturday evening round patrolling the streets of Petts Wood hollering out ‘classified’ – the 6d (2½p) pink edition, with all that day’s football results, having been delivered by train at about 6 p.m..

I had attended the obligatory Sunday school and cubs and now, as a teenager, progressed onto Scouts and youth hostels. Collecting stamps, tea cards and vinyl records of Cliff Richard and Adam Faith (played on my Dansette), it was only the partial destruction of ‘my’ woods opposite my home (in connection with the Kent Coast Electrification scheme that, at St Mary Cray, made it a four-track railway), that the earliest indication of an interest in trains manifested itself. Normally served by a mundane selection of EMUs at about 6 a.m., just as I was getting up for my paper round a coast-bound steam train deigned to call there. Then, about midday, witnessed only during the school holidays, a steam-hauled freight train, worked by a class later recognised as an N or U, called there collecting empty coal wagons and letting all around know when it was struggling away up the 1 in 100 with its increased load.

Then there were the twice-yearly trips to Dad’s home city of Leicester. My brother went with him during the summer whilst I, being older and more able to carry the presents, went with him each December. The only day Dad wasn’t running his pharmacy was a Sunday and, after waving to Mum from the departing train at St Mary Cray, we made our way to Marylebone for a journey down the ex GC to Leicester Central. Met by relatives, we called at his brother’s for dinner at Evington Close, his sister’s for tea at The Highway (where I noted the maroon and cream-liveried Leicester Corporation buses passing the window whilst everyone else was talking) and his dad’s at Dulverton Road. It was always the same circuit – being returned to the station about 7 p.m. courtesy of someone’s car. What locomotives were we hauled by? Nothing was noted. Gresley A3s or V2s – who knows!

There was, however, change afoot. During 1960 the Sunday services out of Marylebone were withdrawn and we had to travel out of St Pancras to Leicester’s London Road station. Stanier Scots and Jubilees must surely have been at the front – all regrettably not being recorded! The cross-London journey was now from Elephant and Castle via the Northern (City branch). I can still visualise the single 12ft-wide island-platformed Angel station, which was deemed sufficiently unsafe to be rebuilt in the early 1990s. Upon departure, from there I looked forward in anticipation to the deep drop, akin to a roller coaster, before arriving into King’s Cross/St Pancras.

As to the return journey, I remember there was one occasion when, having been delayed by thick fog and snow en route, Dad and I eventually arrived at Elephant and Castle in the early hours of Monday morning. Not to worry, with trains departing at 01.25, 01.56 and 02.23 for Orpington we were still able to reach home. The SR ran these trains to entice Fleet Street print workers to live in the suburbs. Annoyingly, I was still dispatched to school that morning!

Meanwhile, following a series of must-do-better reports from school together with slipping down a stream, Dad decided (I was 15½) that it was pointless me staying on in order for me to fail the Royal Society of Arts examination (a qualification he said would get me nowhere) and I might as well follow his advice to ‘get yourself a job’. Parents are in life to guide their offspring and I can never thank them enough for setting me up in a career within the railway industry. They had noted my interest in timetables and wrote to the SR HQ at Waterloo on the off chance of a position in the Telephone Enquiry Bureau – whose prime objective was to assist prospective customers with their journey arrangements by reading timetables. Having passed the necessary entrance exam and medical, I commenced working for BR in June 1962 – the catalyst of a fulfilling forty-five-year career at a dozen or so train planning offices.

So now I was in situ, so to speak, to commence my lifelong love affair with the steam locomotive. But, as so often when such opportunities happen in life, one tends to miss the beckoning signs. I had joined BR purely as a job. Initially, I had little or no interest in steam. It was others I worked with who highlighted that it would be naive of me not to take advantage of the travel perks associated with my employment, thus enabling me to see the world at a far cheaper cost than Joe Public.

And so I began, cautiously at first and concentrating on my home patch of the Southern Region, to venture out to destinations to which I had often directed callers. Into 1963 and I began visiting lines threatened under that year’s ‘The Reshaping of British Railways’ as compiled by Doctor Richard Beeching. I discovered that the majority of those lines retained steam traction and, coupled with lunchtime visits to the ‘spotters’ end of Waterloo’s platform 11 to witness the 13.30 Pacific-powered Weymouth departure, slowly and surely the attraction became irresistible, intoxicating even.

As the steam locomotive’s reign was coming to an end the numbers of followers increased dramatically. For sure the majority were platform-enders, filling their ABCs with whatever came along, but a minority were hard-core haulage bashers. Without initially appreciating it, I was to morph into one of them – gallivanting around the country purely to travel behind as many different locomotives as possible before their inevitable demise. Our remit was to have actually travelled on the train that was worked by a particular locomotive and then, and only then, could you score though or underline it in your ever-present Ian Allan Locoshed/ABC/Combined Volume. Indeed, Ian Allan (1922–2015) has long been considered the spiritual father of trainspotters. His publications, which in turn provided the necessary detail so central to a ‘gricer’, are alleged to have kept thousands of teenagers off of the streets and out of trouble. What would today’s adolescent generation think if we stated that it was a completely acceptable, normal even, activity to undertake during the early hours of a Sunday morning, rather than any of the more typical goings-on they might have been up to back in the 1960s, to be aboard steam trains arriving at and leaving Manchester! Other innocuous pastimes similar-aged lads undertook were collecting records, stamps, Dinky toys, matchbox labels, birds’ eggs, butterflies; we collected steam locomotive numbers – so what?

It had to be done. We felt obliged to record the end of steam. As time went by, with fewer and fewer trains being steam operated it was inevitable that our paths began crossing on a far more frequent scale. The camaraderie that was created back then is still prevalent amongst today’s survivors. You don’t need confirmatory documents as to where you were and what trains you were on. It is all stored within each individual’s memory bank. These days, as soon as like-minded haulage bashers from the 1960s see each other, the greatest likelihood being at the wonderfully organised galas most of the larger preserved railways run, the conversation quickly returns to those halcyon days. If one of the visiting locomotives, having been specially brought in by road for the event, had been caught back in its BR operational days by one of us but not the other, a somewhat (with a waving motion in front of the mouth as if muting a trumpet) exaggerated yawn, indicating boredom at the fact that was so common back then, pervades the carriage. The followers were classless. Rich or poor, privileged or working class – all backgrounds with a common aim. I often wondered how those who did not obtain cheap travel as an employment perk could afford it all – but then again ticket checks on trains were infrequent and there were no automatic barriers back then!

It was alleged in an article in The New Society magazine (August 1986, author Lincoln Allison) that there were, at the most, a mere 300 genuine haulage bashers. Nearly all were English, a surprisingly high (he wrote) proportion of whom were BR employees – usually from the clerical or lower management grades, and that, their activity being incompatible with stable relationships with the opposite sex, they didn’t bother to wash, when in full cry of their hobby, for several days. He went on to say that, unlike a great many other hobbies, no trophies were presented, no collections mounted – their sole achievement being books, which, on relevant pages, have lists of numbers underscored. As to my response to all the above; I plead guilty!

Anyway, back to the centre of attention – the steam locomotive itself. The condition many of the steam locomotives were to be found in can be seen in the photographs accompanying this tome. Filthy, run down, externally neglected (but by necessity safe to run), numbers and names missing – it only added to the aura. To many older enthusiasts, reared in the days of smart, gleaming locomotives proudly displaying their companies’ colours, the sight of them in the depth of their degradation must have been abhorrent. For more recent generations such as myself, however, it was all we ever knew and photographs of that era are still fondly cherished as the years slip by.

The April 1965 edition of the Ian Allan Combined Volume. This contained all steam, diesel and electric numbers for the entire country and was an essential guide for any serious spotter.

For sure, the drivers and firemen worked their socks off in attempting to get their steeds to perform the Herculean tasks demanded of them. The writing was, however, on the wall. The sword of Damocles was hanging over the steam locomotive; it didn’t fit in the newly emerging modern era of BR – and indeed Britain itself. Sheds, falling into dereliction, had become surrounded in an abominable amount of dirt and neglect. They were knee deep in ash and coal, making them hazardous to negotiate, hence the foreman’s frequent retort upon being requested for permission to have a look around: ‘I haven’t seen you.’ The locomotives themselves seemed to leak steam and smoke from all manner of orifices not designed for such an activity. They usually, however, unlike their replacement modes of power, which would fail at the wrong turn of a switch, got you where you wanted to go. I was part of a fortunate generation criss-crossing the country on steam trains. From the magnificent Pacifics to the humble tanks, the smoke and sulphurous smell of burning coal, the whistles and a myriad of noises associated with a living machine – it all made it worthwhile.

For many of us we were discovering the world at large. Allowed away from our comfortable existence at home, we had to deal with all those situations never encountered before – strange locations, different dialects, inebriated waiting-room occupants having missed their last train home. We made mistakes. We were tired and hungry. We misread timetables, overslept – it was all part and parcel of life’s experiences – and I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. The sights seen, places visited – they would never have warranted attention if steam hadn’t taken us there. Like acne, homework and the first pair of trousers, it wasn’t just a hobby, it was part of growing up, our life – and our best friend was to be taken from us in August 1968.

Ian Allan appreciated that trainspotters’ pocket money might not have stretched to purchase the Combined Volume and so he published two steam extracts at the more affordable price of 2s 6d. Here is the May 1964 issue of part 2, where all locomotives numbered from 40000 upwards were listed – part 1 being those up to 39999.

My case and equipment – always with me as if attached by an umbilical cord.

Through all the travels contained within this tome my small attaché case (16in × 10in × 4in) went with me. All necessary requirements were contained within it: timetables, camera, Ian Allan books, notebooks, Lyons fruit pies, Club biscuits, pens, flannel, handkerchief, stopwatch, cartons of orange drinks, sandwiches and, of course, a BR1 carriage key – for use in emergencies! Sturdy enough to sit on in crowded corridors of packed trains and doubling up as a pillow (albeit hard!) on overnight services, it was in regular use through the final years of BR steam and even travelled with me throughout Europe. Having survived many domestic upheavals over the years, it now enjoys a comfortable retirement at the bottom of my railway cupboard at home – containing all the documented travel information, without which I could never have contemplated writing a book such as this.

As for apparel, the anorak was not in existence then – to the best of my knowledge it was either a raincoat or a duffle coat with its attendant toggle fasteners. A selection of clothing we all wore back then can be seen within the group photographs at various locations throughout the book. Usually having commencing weekend travels directly after a day’s work at the office, the obligatory tie (modern and straight edged) was always worn – albeit at peculiar angles after many nights out.

As mentioned in the introduction, this, my fifth tome, concentrates on the former London Midland Region. Even with the Carlisle area having being adequately catered for within Scottish Steam’s Final Fling (published 2017) and my travels over the former GWR Paddington to Birkenhead main line and Wales being held over for a future book, if I was to detail every train travelled on throughout the LMR I suspect the publisher/reader would suffer apoplexy. I have therefore compacted my travels into a series of chapters, which, I hope, will enable the reader to read at leisure, perhaps allowing a drip feed of their own memories to infiltrate them.

My Kodak Colorsnap 35 camera.

List of London Midland Region sheds extant at the beginning of my travels.

Furthermore, I would respectfully point out that this book is by no means a definitive account of the last days of steam. There have been a myriad of publications, usually circulated whenever a commemorative date occurs, over the years dealing with that aspect. This is one man’s personal observations and travelogue of what he witnessed and photographed during the final forty-eight months of steam on BR’s London Midland Region. Having confessed to all the reasons behind my belated appearance on the steam scene, here we go …

1 London Transport Red Rovers covered all Red Routes 1–299 that operated within Central and Outer London, while Green Rovers were for Country Routes 300 onwards that operated within the surrounding Home Counties.

2

VOYAGE OF DISCOVERY: 1964

Initially concentrating on the many line closures throughout Southern England, it was in August 1964 that, having been invited to use their Leicester home as a base, my father’s brother’s family offered me the opportunity to explore the world away from my home territory. Many hours of studious scrutiny of the maroon LMR timetable, together with magazines such as The Railway World detailing the latest lists of proposed line closures, led me to compile the itinerary as followed in this chapter.

Manfred Mann’s ‘Do Wah Diddy Diddy’, having displaced The Beatles’ ‘A Hard Day’s Night’, was holding the top spot and, earlier that month, the last British hangings at Strangeways and Walton jails had taken place. Other UK newsworthy events were John Surtees winning the German Grand Prix; the first broadcast of TV’s Match of the Day with Kenneth Wolstenholme and Great Train Robber Charlie Wilson escaping from Birmingham’s Winson Green prison. World events such as the escalation of the Vietnam War, The Beatles touring the USA and Canada to packed stadiums and the deaths of James Bond creator Ian Fleming and singer Jim Reeves were far from my thoughts – I was totally preoccupied by the anticipation of travels to ‘foreign lands’.

Although having travelled on overnight services to the West of England the previous month, the familiarity of destinations already known both from having holidayed there over the years with my parents and my SR telephone enquiry job, voyaging north that August night it seemed I was venturing into the unknown. Sure I had studied maps, viewed photographs and read timetables about the cities and towns I was to visit but nothing broadens the mind like actually visiting them in person. Strange dialects, unusual-sounding destinations – it all caused an adolescent 17-year-old some consternation when determining if I was on the correct train/platform to ensure my plans were adhered to. The overnight service down the ECML, specifically advertised for Geordies working away during the week to visit home with cheap tickets, was chock-a-block. This service called at all main stations; the consequential tramping through the open carriages of passengers looking for non-existent seats resulting in very little shut-eye being obtained en route. Upon arrival at Newcastle I was glad of the opportunity to stretch my legs and, albeit a little weary, the two hours there seemed to pass very quickly. Not particularly conversant with the station layout, I fortuitously positioned myself at the north end of the station and was thus able to view both the famed diamond crossing and the goods lines – watching and photographing a plethora of steam locomotive classes only previously seen in The Observer’s Book of Railway Locomotives.

For those readers interested in football facts, Newcastle’s 1964–65 season had yet to kick off. When it did the following Monday they were held to a 1–1 draw at St James’ Park by Charlton Athletic.

I had been advised, by those more knowledgeable than I, that Preston was a Mecca for steam activity and so I made my way across the north of England to Carlisle, from where I had by chance selected a steam-hauled Newcastle–Blackpool service to travel south over Shap; Carnforth’s 45209 becoming my first of an eventual 289 (so far!) haulages behind one of Stanier’s competent Class 5MT workhorses. After arrival into Preston, I went searching for a B&B, luckily finding one within a stone’s throw from the station. Then, after depositing my case, I returned to the station in order to complete the final objective of that day – namely travelling over the whole of the Fylde peninsula’s railway network.

The first line constructed on the Fylde peninsula, between Preston and Fleetwood, was opened by the Preston & Wyre Joint Railway in 1840. Until the railway was built over Shap this then was the main route for passengers from London to Scotland, utilising a ferry from Fleetwood to Ardrossan. Indeed, Queen Victoria herself travelled this way in 1847. The primary employment for the Fleetwood townsfolk, that was until the Cod Wars with Iceland, was the fishing industry – the town’s landlubbers being catered for by the 1865-built factory producing the world-famous Fisherman’s Friend lozenges. Because the Fleetwood branch was on the Beeching hit list I, with difficulty due to the sparse service, made it a priority to travel over it: one of the thirty-strong class of BR 2MT 2-6-2Ts, 84010, powering that day’s trains. It was fortunate that I did because in April 1966 the line was truncated at Wyre Dock – passenger services over the complete line ceasing operation four years later. The line, however, could have a future as not only is there pressure from the local council to reinstate passenger services, the line has been ‘mothballed’ as far as Burn Naze since 1999. Watch this space.

This publication was a present from ‘Uncle’ Ben for Christmas 1963. He was actually a fellow pharmacist friend of my dad who he met at college when studying medicine. Once a year he ran my dad’s shop, staying in our home, allowing us to take an annual break.

This and the following two photographs were taken on Saturday, 22 August 1964. My initial thoughts were, having recently discovered that no print had been developed from it, that it was of my first train over Shap after its arrival into Preston. Upon Railway Images expertise being applied it appears to be one of 4-6-0 44947 calling at Preston on a completely unrelated train. Little did I realise then that in just under four years’ time I would depart this very platform on Britain’s final public steam-hauled passenger train.

Carnforth-allocated Stanier 5MT 45326 about to pass under the Fishergate Road bridge at Preston with a Blackpool-bound service.

In 1846 a branch from Poulton-le-Fylde to Blackpool was opened. Renamed Blackpool Talbot Road in 1872, it acquired its final appellation of North in 1932. Eventually enlarged to accommodate sixteen platforms, it was threatened with closure in 1963 but survived – the local council underscoring the fact that the Central station’s site was of greater land value. Indeed, in 1911 Blackpool Central was alleged to be the busiest station in the world. Although Dr Beeching advocated that Central be retained in preference to the North, money spoke and the council got its way: indeed, a further land grab was made by relocating North station to the site of the former excursion platforms in 1974. The Blackpool & Lytham Railway, first opened in 1863, extended its line eleven years later along the South Fylde coast to Kirkham – renaming its town terminus from Hounds Hill to Central in 1878. The final line in the equation, the Marton direct, was opened in 1903, joining the line to the Central at a newly created Waterloo Road, renamed Blackpool South in 1932.

Blackpool Central was closed in November 1964 – the ground being deemed more financially valuable to the money-strapped BR than its substantial seasonal usage. Naively being more intent on track coverage on the day I returned to Preston via the Marton direct, on a DMU to boot, thus losing out on the only chance I ever had for a run with a Patriot. Carlisle Upperby’s 31-year-old 45527 Southport together with Newton Heath’s 45339 were no doubt returning day trippers to their Lancashire homes having had a glorious day on the beaches and in the funfairs.

The following day, Sunday, 23 August 1964, having spent my only night in a B&B in Britain whilst chasing steam, Stanier 2-6-4T 42645 awaits departure time at Preston with the 13.25 for Southport Chapel Street. This West Lancashire Railway-built line via Hoole and Crossens was to close the following month – the 1938-built 4MT Southport-allocated locomotive surviving until July 1965.

All of these lines were in situ when visited that day and, by astute planning, travelled over. Although Black 5s dominated most trains that day, I witnessed, but alas failed to acknowledge the significance of, one of the few remaining Patriots, 45527 Southport, at Blackpool Central. Although I prioritised a trip over the subsequently closed Marton direct line, now part of the M55, with hindsight I regret snubbing a ride with a Patriot: an opportunity lost forever. I consoled myself with the fact that at least I had visited Blackpool Central, which closed just three months after my visit.

Retrospectively, upon the realisation that overnight train travel was not only cheaper but also enabled greater steam mileages to be gathered, this stopover between clean sheets became the only occasion during four years of travels throughout Britain that I acquiesced to such comfort. That, however, on the first ever night on my own, was not to be known then and snuggling down into the comfortable bed listening to the novelty for me of night-time steam activity resonating from the nearby station, I fell into a fitful sleep.

The following day, a full English breakfast having been consumed, time was spent that Sunday morning at Preston station – the consistency of Stanier tanks on local services and Jintys on shunting duties being broken by Upperby’s Southport, together with many Black 5s, storming through the station taking day trippers to Blackpool. I wouldn’t have known then that, resulting from the contraction of steam services elsewhere in Britain over the coming years, this station was to become a magnet for steam enthusiasts and I was to spend a great many hours festering (to quote modern parlance) in the often forlorn hope that ‘required’ locomotives would materialise. It was a very hot day and with the train selected in order to make my way via Leeds to Leicester being a DMU, I had no alternative but to suffer and sweat on the two-hour journey via Colne.

Station pilot duties at Preston during 1964 were still in the hands of the elderly Jintys. Here 0-6-0T 3F Hunslet-built 36-year-old 47564 is on carriage-shunting duties. After withdrawal in March 1965 she ‘sort of’ survived into preservation – being used as spares at the Midland Railway Centre at Butterley!

Colne was originally opened by the Leeds & Bradford Extension Railway, from Skipton, in 1848 becoming, a year later, an end-on station with services operated by the East Lancashire Railway from Blackburn. In its heyday Colne had through services to Yorkshire, Blackpool and London’s Euston, but by the 1960s falling passenger numbers saw services truncated at Preston and Skipton – the line north to the latter closing in 1970.

So now, after six hours of travel, I arrived at my father’s hometown of Leicester. The first railway into the city was the Leicester & Swannington Railway of 1832 at West Bridge, followed eight years later by the Midland Counties Railway between Derby and Rugby. In the June of 1841 cabinetmaker Thomas Cook put forward an idea to a Leicester temperance meeting that they run an excursion by train to another one based at Loughborough. After receiving the OK from the Midland Railway Company, on 5 July that year a total of 500 persons were conveyed the 12 miles to Loughborough for the princely sum of 1s each – the rest is history.

Initially utilising that route to Rugby, thence via the LNWR (née London & Birmingham Railway) to access London, in 1857 the Midland Railway opened up their direct route via Bedford to Hitchin and the GNR to King’s Cross before, in 1868, arriving at their own London terminus of St Pancras. Thus Leicester, further assisted by the arrival of the Great Central in 1899, with its improved transport links was able throughout Queen Victoria’s reign to attract a multitude of fleeing European refugees to its wide diversity of industries – a situation very much relevant today.

A newsworthy event in September 2012 was that of Richard III’s remains being discovered during an archaeological excavation of a car park – he was then reburied in Leicester cathedral. Sports-wise, Leicester City football club (known as the Foxes) were the unexpected 2016 Premier League winners, having had many mediocre years within the top two divisions of the football league. Earlier that season, Leicester-born Match of the Day presenter Gary Lineker had vowed that in the unlikely event of them winning the title he would present the programme in his underwear – a promise fulfilled that September. Meanwhile, another Leicester-born sportsman, Mark Selby (the Jester from Leicester) has been a three times world snooker champion.