11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

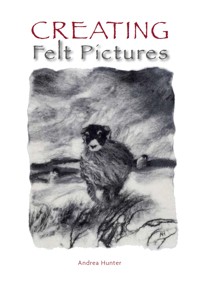

Feltmaking is a popular medium for craftsmen, but few have explored its potential as an art form. This new book demonstrates the exciting scope of pictorial feltmaking and explains how to create felt pictures with the depth and atmosphere usually associated with a graphite drawing or a watercolour painting. Written by a leading felt artist, it shows how to work freely with the wool as if it were paint or a piece of charcoal. Covers essential feltmaking skills for the beginner, as well as techniques and inspiration for the more experienced feltmaker, with advice on how drawing and painting skills, such as perspective composition and the use of colour, can be applied to felt pictures. Illustrated with stunning pictures of finished works, as well as practical demonstrations, it also includes a guide to the presentation and framing of work.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 126

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Copyright

First published in 2012 by The Crowood Press Ltd, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book edition first published in 2012

© Andrea Hunter 2010

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 978 1 84797 468 6

Frontispiece: A Place to Grow – central panel of a triptych.

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

INTRODUCTION

1 INSPIRATION

2 MATERIALS AND EQUIPMENT

3 ESSENTIAL FELTMAKING SKILLS

4 DRAWING WITH WOOL

5 PAINTING WITH WOOL

6 ADDING EXTRA TEXTURE

7 PRESENTATION AND FRAMING

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

GLOSSARY

FURTHER READING

USEFUL ADDRESSES

INDEX

Nature’s Cloth, 4 × 4m (13 × 13ft).

INTRODUCTION

My interest in using felt as a medium for pictures grew from my desire to express, artistically, the landscape at my door. I was aware that memories, feelings, experiences and social connections had an important effect on how I viewed my surroundings and thereby had a strong influence on my ideas about sense of place and feelings of belonging. Researching the art of felt making, I was struck by the versatility and other properties of this fabric and also, equally important, I became aware of the impact felt and felt-making has had in contributing to cultural identity across the world.

Felt is the oldest material known to man and pre-dates knitting and weaving. The making of felt can be dated to as far back as 6300BC and ancient writings record how it was used to make clothing, tents, saddles and blankets. The oldest piece of felt known to exist dates to around 700BC and was found in the Siberian Tlai mountains in the tomb of a nomadic horseman. Many people believe that felt was first made by accident when wool was used to protect the feet of travelers whereby the process of movement, pressure and perspiration caused the fibres to compress and create a matted fabric. Felt is fundamental to the nomadic peoples’ rich heritage. In countries such as Turkey, Tibet, Mongolia and Russia, it provides for a range of essential needs – tents (yurts) made from sheep’s and lambs’ wool; carpets for furnishings, prayer and burial mats; bedding for sleeping; clothes and shoes; gifts between families; thread made from camel wool, and rope and ribbons, made from yak and horse hair.

Having some knowledge of felt – its making and use in different cultures worldwide, from ancient times to the present day – stimulated my own ideas about utilizing a medium with which I had some local connection and which has influenced ideas about my own sense of belonging to a distinct community. I found that sheep, both in reality and metaphorically, were central to the shaping of my landscape, community and identity. To try to express my connections, I then began experimenting with making images of sheep in their landscape, utilizing what could be termed as ‘hybrid’ art, which incorporates a painterly approach to wool to produce a scene and then subjects the ‘picture’ to the felting process. Thus by drawing from the two influences of painting and felt-making, I can express my own personal affinity with the surrounding landscape, in a way which I like to think echoes that of other societies, in which creativity is linked to the same sort of belonging as mine.

My relationship with the landscape of the Yorkshire Dales stems from my upbringing as a member of a sheep farming family in Wensleydale, where the way of life is closely connected to the day to day activities involved in the breeding and rearing of sheep – lambing, clipping, dipping, fothering, sheltering and hay-making. In the past, farming activities had more of a communal input; for example, farmers worked together to gather in the sheep from the fells for clipping and dipping and helped each other getting in the hay for winter feed, or working together to rescue sheep from under the snow in a winter blizzard. These kinds of activities forged the bonds of community. More local people were farmers, shepherds or agricultural workers, and farmers’ wives and children were involved in a supporting role. Mechanization, new technologies and diversification have brought many changes on the farm and these have impacted on the landscape and community, changing my relationship to both, and introducing new ways of experiencing them.

The women of my past community have been a rich stimulus for my art – their imaginative resourcefulness was a quality much in evidence in their everyday lives. For example, making stobbed or prodded rugs was a communal project and whoever was lucky enough to have a mat in the process of being made, would have a weekly night when several other village women would gather to help, in exchange for refreshments and a catch up on village news. The mats were made with recycled material ‘clips’ and usually included old woollen garments that had shrunk in the wash and accidentally felted. When the rugs were finished they were much admired, with their unique designs, cacophony of colours and reputation for being extremely hardwearing. Other creative pursuits undertaken were dressmaking, knitting, haberdashery, embroidery and quilting, and were usually undertaken in the evenings. My own mother was competent at making all types of clothing and well into her eighties she was still making mats and embroidered wall-hangings. Whilst these activities had a largely practical use, being creative was also a way of responding to the environment around them and established a pulse in women’s lives that was both enriching and sustaining.

I like to think I have an affinity with these women of this bygone age and yet have also assisted in pushing back the boundaries of the ancient craft of felt making. I have been fortunate in practising my art in a time when there is somewhat of a renaissance in the handmade product. This renewed interest has contributed to an increase in small craft industries in rural areas. In the Dales the main economy was traditionally agriculture, but the tourism and craft industries are now making substantial contributions to the rural economy. The success of these small industries has been helped greatly by the Internet creating opportunities in a worldwide market.

Belonging to a place or particular area is getting rarer in our world, especially where more and more people are migrants or displaced, often due to the effects of conflict, global warming, unemployment, or for other economic or social reasons. Over time the displacement of people can result in traditional crafts and techniques been forgotten, therefore, with the world’s constantly shifting population, it is very important that we pass on our traditions. Change is inevitable and the development of new ideas is very exciting, but in our enthusiasm to be creative we should always be sympathetic to the traditional skills. Understanding traditional feltmaking, gives the contemporary feltmaker a greater appreciation of the skills involved and in turn can often inspire new ideas. My personal creative journey is ongoing, winding through new ways of seeing and old ways of understanding, giving nourishment to my vision and love of textiles.

Pennines (detail).

Highland cow, pencil sketch.

CHAPTER ONE

INSPIRATION

Inspiration can be gained from all aspects of life and one’s surroundings. Artists, musicians and poets have all been inspired to create, and their work in turn inspires others. Inspiration is very personal to the individual: thus a piece of music that stirs one person may leave another completely cold. Also our preferences change as we get older and experience more of life. Generally the young have a hunger for all that is fast and exciting – they are full of vigour and passion, whereas as you grow older you become more closely connected to the world spiritually. I have a deeper empathy with my surroundings, the world and my place within it now than when I was a student and everything was new and exciting.

I find inspiration not only in other artists’ work, but also in the Dales’ landscape, its inhabitants and particularly in the dramatic contrasts that the Dales’ weather brings. I try to capture a sense of movement in my windswept landscapes by working with fine layers of wool as if it were paint. It is this technique, and a strong illustrative dimension, which makes my work distinctly different from traditional felt artwork, and one which I hope inspires others to experiment with feltmaking – and specifically painting with wool, as this exciting technique may change some people’s approach to feltmaking and broaden their views about art and craft.

When looking for inspiration before embarking on a piece of artwork, start by looking at the things you like because you are more likely to be inspired and to realize your best effort if you choose a subject that interests you. Music is a great way to stir your feelings of creativity: listen to some favourite tracks, whether classical or heavy rock – whatever appeals to you or is conducive to the situation. When trying to capture a wild moorland landscape with the wind blowing in heavy rain clouds, I often play very loud rock music because the energy of the music helps me recall the energy of the elements out there on the moor.

Try to connect with your chosen subject: go out and physically experience it – taste it, smell it, feel it, collect all the visual information you can about it in the shape of photographs, magazine cuttings, sketches and the actual object if possible: you can never have too much information. In short, know your subject. Having a good knowledge of your subject is key to a successful interpretation. Much of my work is inspired by the Dales’ landscape which surrounds my home, and I am lucky to have inspirational views from my windows – but so often I find myself relying on memories from long ago, as well as perhaps yesterday’s walk. My memories hold not only visual images, but also feelings, emotions, smells and the elements, and I draw on all these things to help me put together an image: the smell of the wet peaty ground, the wet fleece of the sheep and the wind on my face, all natural elements of the fells and so much a part of growing up on a hill sheep farm. Sketching also plays an important part in stimulating fresh ideas and perspective in my own work, even though living in the Dales’ environment means that I know my subject well.

Racing Hares (individual hares 60cm/24in).

When searching for inspiration it is very useful to look at other artists’ work, to study the medium used, and how they have interpreted the subject. Over the past ten years I have been inspired by several artists. Henry Moore’s sculptures and drawings have been a real inspiration to me, in particular his Sheep Sketchbook, which is such a joy to peruse: flicking through the pages I smile to myself as I recognize in his drawings many of the poses typical in our own sheep. He captures their solid form so brilliantly, along with their innate character. He obviously spent many hours studying their physical form and observing their individual characters. Studying his sculpture and drawings has helped me to realize a three-dimensional quality in my own work.

On a recent visit to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park I was also impressed by the work of Sophie Ryder, an artist working with wire. Her huge, free-standing wire sculptures of the Lady-Hare, a hybrid figure combining the hare with human features, form powerful images full of emotion and character. The subtle characteristics of the hare are sympathetically portrayed in the rusty wire with which she works so successfully. Her beautiful wire drawings combine the skill of a drawing with the tactile qualities of sculpture. These works inspired me to develop my own images of hares, creating the figures in isolation and exhibiting them running across the gallery wall. Looking at sculpture and studying the solid three-dimensional forms helps me in forming my pictures because I work with the wool in a very sculptural way, taking into consideration light and shade, employing techniques to give weight and solidity to a form, actually forming the shapes with the wool, adding a little here and taking a little there, thus creating a sense of depth and a three-dimensional quality.

In the feltmaking world the late Jenny Cowen was a great inspiration. I was fortunate to meet her early in my career, and exhibited with her in 2002. Her subtle use of tone and colour is truly amazing, in particular in her seashore pieces depicting smooth pebbles on a sandy beach amidst the swirling rising tide. Her images are soft and full of depth, and convey a tranquil quality. In observing her work it was clear that she was a true artist working with wool, as her drawing skill was very apparent. This was the first fine art feltwork I had encountered, since everything I had seen up to that point had had a functional element. Jenny’s work therefore had a lasting effect on me.

Visiting galleries and exhibitions is a great way to be inspired, as looking at original works can often trigger ideas for one’s own work, even when the pieces may seem very obscure and unfamiliar. This is especially useful when you feel the need to refresh your own work or change direction. Never copy the work of others, merely absorb it and let it feed your own creativity.

Collecting visual stimulation is vital to the creative person, and sketching and photography are two of the most effective ways of doing this.

Sketching and Drawing

In these days of the slim, pocket-size digital camera, which can capture an image at the click of a button, it might be argued that the sketchbook is irrelevant – and in one respect this would be right. To simply record a situation or subject, the camera has triumphed over the sketchbook – but the sketch has far greater merits than that of a simple recording tool. The great discipline that sketching demands is observation, and to create a successful sketch you must look repeatedly at the subject. This practice teaches you to really examine a subject, and with practice your hand–eye coordination improves and the whole experience becomes easier and more enjoyable. Carrying a small sketchbook and pencil around in your pocket then becomes a habit, and it becomes an invaluable tool in your creative process.

The watercolorist and the oil painter can both paint outdoors, but for the felt artist working with fine layers of wool this is an impossible pleasure, as the slightest breeze lifts the fibres and transports them elsewhere, destroying the felt picture in the process. Therefore as a felt artist, the good outdoor sketch is a very valuable resource once you get back to the tranquillity of the studio. As the sketch is generally used for reference