4,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

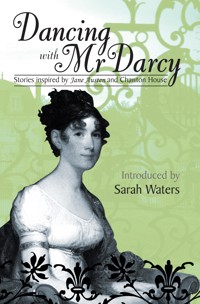

- Herausgeber: Honno Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

From Jane Austen's regency readers to fans of television's wet-shirted romantic, there have been thousands if not millions of us who've hankered after a hero to match the eponymous Mr Darcy. The 20 original short stories in this collection have been inspired by the novels and characters of Jane Austen, or Chaton House, a place she knew and loved - a fertile playground for the writerly imagination... Sarah Waters introduces her slection of these stories submitted to the Chawton House Library Competition 2009.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Ähnliche

Contents

Title PageForeword – Sarah WatersIntroduction – Rebecca SmithJane Austen over the Styx – Victoria OwensSecond Thoughts – Elsa A. SolenderJayne – Kirsty MitchellThe Delaford Ladies’ Detective Agency – Elizabeth HopkinsonTears Fall on Orkney – Nancy SaundersEight Years Later – Elaine GrotefeldBroken Words – Suzy Ceulan HughesMiss Austen Victorious – Esther BellamyCleverclogs – Hilary SpiersSnowmelt – Lane AshfeldtThe Watershed – Stephanie ShieldsSomewhere – Kelly BrendelThe Oxfam Dress – Penelope RandallMarianne and Ellie – Beth CordinglyThe Jane Austen Hen Weekend – Clair HumphriesOne Character in Search of Her Love Story Role – Felicity CowieSecond Fruits – Stephanie TillotsonThe School Trip – Jacqui HazellWe Need to Talk about Mr Collins – Mary HowellBina – Andrea WatsmoreAuthor biographiesJudges’ biographiesABOUT HONNOCopyright

FOREWORD

From Bridget Jones’s Diary to Bollywood’s Bride and Prejudice, from the Regency-horror mash-up Pride and Prejudice and Zombies to the forthcoming sci-fi film Pride and Predator, it seems that Jane Austen’s work is being appropriated by contemporary culture in ever more playful and creative ways. The fact that most of the modern interest in Austen converges on just one of her novels, however, suggests that the role she plays for us might actually be dwindling, even as her presence around us seems to be on the increase. It’s as if Pride and Prejudice has become a sort of shorthand for a whole style of literature, distracting us from the range and depth of its author’s work, and offering us instead a cartoon Austen, a thing of fussy bonnets and silly manners, easy to pastiche. When I was approached by Chawton House Library and invited to judge the final stage of the short-story competition which formed the basis for this anthology, I was delighted, but also trepidatious – fearful that I would find this cartoon Austen reproduced in the stories I was asked to judge; that I would encounter nothing but Elizabeth Bennets engaged in perpetual pallid dalliances with cardboard Mr Darcys.

But my first glance at the longlisted entries was reassuring: I saw some startlingly unAusten-like titles, and an impressive array of settings and styles. In fact, so individual did the stories prove to be, the process of assessing each against its competitors became a highly challenging one. Feeling I needed to lay down some ground rules, I decided on three main criteria. First, it seemed to me that I had to be looking for something well written – a concept which, I fully understand, can mean different things to different people, but which for me meant something written with flair, by an author with an obvious talent for putting words together; but something written with skill and confidence, too – something to make me feel that, as a reader, from the first word to the last I was in good hands. Second, since this was a short-story competition, I also wanted to see stories really working as stories: there were some lovely pieces of writing that I rejected, regretfully, because they felt to me like fragments of prose, rather than the well-crafted, self-contained structure I felt a good short story should be. And finally, since this was a Jane Austen short-story competition, I wanted the stories to have some really meaningful connection with Austen herself. I was pretty flexible about this. As far as I was concerned, the connection might have been a very obvious engagement with the novelist, her work, her Chawton home or Chawton House Library; or it might have been something much more abstract; but I felt it needed to be there.

Each of the stories selected for this anthology meets all of these criteria: each is well written and well crafted, and between them they use Austen and her work in diverse and quite fascinating ways. A few are directly inspired by Austen’s texts – ‘Somewhere’, for example, teases out a new story from between the lines of Mansfield Park to give us a poignant study of compromise and loneliness. Others are true to the spirit rather than the letter of Austen’s novels; none is ‘romantic’ in the conventional sense, but many show youthful protagonists dealing with desire and attraction – suggesting that, although young people in thetwenty-firstcenturyhavethekindofsocialfreedomsthatwouldhavebeen unimaginable to their Regency counterparts,loveandcourtship remain thrilling but difficult to manage.StillothersreflectonthemeaningofAustenforhermodernreaders–withboth ‘Snowmelt’ and ‘Cleverclogs’, for instance, indifferentwaystestifyingtothepowerofreadingitself,andremindingusofthecontinuing importance, in our noisy, crowded world, ofthequiet,solitary spaces in which literature can be prioritisedandsavoured.

Giventhestrengthandrangeoftheseandtheothershortstories gathered here, I found it very difficult to chooseawinnerand runners-up. But three stories kept drawing meback.‘Jayne’appealed to me right from the start. I liked its economy, anditsirreverence, and the thoughtfulness with which thatirreverenceis underpinned – for though the world of itsglamour-modelnarratormight at first glance seem far removed from thatofAusten’sdecorous heroines, Jayne’s grip on female economicrealities,andon the strategies available for negotiating them,isactuallythoroughly Austenesque. I found myself haunted, too,by‘SecondThoughts’, an ambitious story, told from Austen’sperspectiveandintheidiomofhernovels,whichattemptstobringtolifeanagonising moment from the novelist’s own romanticcareer.Theresult is a deceptively spare piece of writing, beautifully crafted and paced, infused with real emotional power.

These two stories make very fine runners-up indeed, but it was ‘Jane Austen over the Styx’ that I finally chose as my winner. It’s another story which attempts, and succeeds in, the tricky business of emulating Austen’s voice – this time, to take us on a fantastic journey into Hades, where the novelist is judged by a panel of aggrieved female characters from her own books. It’s a story with a shape, a craft; a purpose: a memorable piece of writing, engaging stylishly and intelligently with Austen’s fiction and reputation.

What all the stories in this anthology show, in fact, is the continuing resonance of Jane Austen for modern readers and writers. None is a simple homage to the novelist, but each, in a sense, is a celebration of her work; and collectively they lead us back to her with fresh eyes. It was a pleasure to read and to judge them.

Sarah Waters

June,2009

INTRODUCTION

Falling in Love withJane

I fell in love with the novels of Jane Austen when I was thirteen. I remember sitting in a 1950s prefab that was more greenhouse than classroom. We had wooden slanting desks, the inkwells stuffed with gum and chewed paper. I would have loved a proper inkwell with proper ink. The school was in Dorking, and the view from the playing fields was of Box Hill. That was the only picturesque element. There was no Mr Darcy. I don’t know if the boys were reluctant to dance as I didn’t go to the discos. I do remember their bobbly nylon blazers, and how skilled some of them were in the trapping and torture ofwasps.

There was a Wickham, a disreputable ginger tom who moved in with my family. We never knew his real name. One day he disappeared (eloped? off with the militia?) leaving me with nothing but rings of flea bites around my ankles. I told people that they were mosquito bites, hoping to give myself the glamorous aura of a girl whose family took foreign holidays during term-time. These were difficult years. We understood only too well the precariousness of some Austen heroines’situations.

It is the appeal of her heroines that makes Austen’s work so enduringly popular. She challenged her readers by offering them characters and heroines who were not always immediately engaging. Many of the competition entrants sought to give voices and new destinies to some of the less appealing or more minor characters. There were hundreds of entries. Reading them was a delight; choosing a shortlist was horrible. Fanny Price, Mary Bennet and Miss Bates (or later incarnations of them) proved to be very popular subjects. I particularly liked a story in which Mary Bennet had a happy ending as a seafarer. I wondered whether the writer of that one had once wished she was Lizzy, but feared that she was more like Mary; I know I did.

The love and appreciation of Austen’s works is evident in the stories collected here. I applaud the winner, Victoria Owens, for having something critical to say, something that goes beyond cap doffing.

So here they are – twenty stories inspired by Jane Austen or Chawton House Library. Let the love affair continue.

Rebecca Smith

June,2009

JANE AUSTEN OVER THESTYX

VictoriaOwens

JANE AUSTEN OVER THE STYX

VictoriaOwens

Travelling to the infernal regions was easy. True, the ferry leaked and the water seeping in through the planks of the hull was dark and cold, but remembering the hardships her brothers must endure in the navy, Jane decided to make light of it. Anyway, she did not think the ferryman would pay much heed to the remonstrations of a lone passenger like herself.

When she reached her destination and disembarked, the long terraces laid out upon the slope above the fiery lake put her in mind of Bath. The climate of the place was mild and the prospect of the distant hills pleasing. Provided that the society was pleasant she could, she thought, reside here with much happiness.

Before she could settle she had, like all mortals, to answer the charges brought against her in the court of the dead. Entering the half-timbered courthouse and making herself known to the phantasmal usher who greeted her, she reminded herself that she was hardly likely to find herself acquitted on all counts. There was no denying her life had had its faults: that tendency to be sharp, especially with her mother; the occasional fruitless burst of resentment at the good fortune of others; and of course that wretched business when she had accepted Mr Bigg-Wither’s proposal of marriage only to change her mind twelve hours later. True the two of them would never have fadged, but it might have caused him less hurt if she had been plain from the outset. On the other hand, she was no Medea, nor Lucrezia Borgia, noryet adulterous Lady Coventry. She had lived within her means and although she had sometimes been short with her family, in truth she loved them well. Had she not taken every care of her sickly mother, even when they both knew the sickness had no existence whatever outside the patient’s fertile fancy?

The usher led her into an oak-panelled room with a gallery at one end and a low dais at the other, on which sat the three austere gentlemen who made up death’s tribunal. For a second, she stood quite still, amazed to see how much the exercise of eternal justice resembled the workings of English law – one of those three presiding judges had even extracted a large bone snuffbox from the folds of his gown and was offering it to his companions before helping himself to a liberal pinch. The sight comforted her; she knew several snuff-taking gentlemen and found them in the main genial and warm-hearted. What had she tofear?

Fingers, bony and cold through her woollen gown, pushed her in the small of the back. The spectral usher was thrusting her with no great civility towards the dock. Disliking his prodding, she entered it at once. The wooden surround reached almost to the level of her eyes – she was not a tall woman – and she found herself surveying the courtroom from behind a row of iron spikes. Her confidence began to sink. In this setting, everything must point to her guilt before the hearing began. But guilt upon what charge? What indictment did she face? Deliberately she stared across the court to get the measure of theprosecution.

Where she had expected to meet her mother’s acid eye, deep-set in the folds of her face, or hear poor, good Harris Bigg-Wither stammer out his grievance, instead she beheld no fewer than six women. Theirs were not faces of women whom she remembered from her childhood in Steventon, nor yet from the Chawton years, and she did not think they belonged to Bath. At the same time,she knew she had seen these fighting chins before. Musing, the truth dawned. The prosecuting counsel were her own creations – Mrs Bennet, Lady Catherine de Bourgh, Mrs Ferrars, Mrs Churchill, Lady Russell and Mrs Norris, whose sharp elbows had thrust her to thefore.

A black-clad clerk rose from his seat at the foot of the dais.

‘Prisoner in the dock, what is yourname?’

‘Jane Austen, sir,’ said Janecrisply.

‘Kindly address your replies to the bench, ma’am. Well, these ladies,’ he nodded to the prosecution, ‘have summoned you here to answer a serious charge: namely, that you, Jane Austen between the years 1775 and 1817 did maliciously undercut the respect due from youth to age, in that when you created female characters of advanced years, you wilfully portrayed every one of them as a snob, a scold, or a harpy who selfishly or manipulativelyinterferes with the happiness of an innocent third party. Do you plead guilty or notguilty?’

She was by inclination truthful – in death as in life, but to give an honest answer was unthinkable. At the same time, the thought of having to lie brought on a rush of confusion. Now, as they stared down at her, their faces inert and colourless, the judges no longer looked so benign. What sentence might they pronounce? Prison? One of her aunts had gone to prison for stealing a piece of lace, and a miserable time she had had of it. That had been in Somerset. Although this place appeared orderly, she did not think its prisons would be as comfortable as those of Somerset, nor yet so civilised.

‘Not guilty,’ shereplied.

‘Counsel for the prosecution,’ the clerk glanced at the terse old women, ‘outline your case if youplease.’

There was a brief babble, an altercation involving Lady Catherine, and then the mistress of Rosings deflated unsteadily upon an upright chair and Mrs Norris, adjusting her bonnet, steppedforward.

‘Your honours, the facts of the case are simple. The issue is that nowhere in her clever books does the irresponsible female in the dock portray elderly women in any true light ofkindness.

‘Look at us. Here is Mrs Bennet who always worked hard for herdaughtersbutwhoemergesinMissAusten’swritingasfoolish and noisy; devoted Mrs Ferrars is made to look grasping, herfriend Mrs Churchill self-absorbed and demanding. The worthy Lady Catherine, so interested in young people’s welfare and so conscientious in setting their feet upon the right path through life, she presents as misguided and supercilious. She would have us believe that even beneficent Lady Russell cared less for her god- daughter’s happiness than for her own. There, your honours, would I rest my case, except that I cannot forbear to remind you that my creator has the temerity to suggest that the true devotion I showed my niece Fanny Price – making her aware of her lowly station, impressing upon her the virtue of frugality, reminding her of every Christian’s call to humility – was no more than crabbed meanness. Here is pure malice. And she directs all her hostility to women who are old. Female kindness and liberality, according to Miss Austen, are youth’s provincealone.’

‘Your evidence?’ enquired the judge on the left-hand side.

‘In these wretched books,’ Mrs Norris asserted, producing the familiar volumes from her reticule and holding them at a distance from her face as though the pages gave off a bad smell. ‘For youth, Miss Austen makes every allowance. Her young women – Elizabeth, Elinor, Catherine and all – have ready charm. Anne Elliot, who is not old so much as faded, proves wiser than her father. The benevolence Emma Woodhouse shows her father counterpoises her impudence and arrogance. Mary Crawfordmay flirt where she should preserve decorum and speak lightly where she should be reverent, but Miss Austen tempers her impropriety by indicating the kindly fellow feeling she bears both towards her sister and, on occasion, to Fanny.

‘Pray where does Miss Austen ever show a woman who is at once old, virtuous and wise? I contend, nowhere. Is not this omission a gross calumny upon the worthiest of our sex?’

‘Would it be fair to add, ma’am,’ the right-handjudgesurveyedMrs Norris through a pair of wire-rimmed spectacles,‘thatMissAusten is not entirely gentle in her dealings with oldmeneither?Mr Woodhouse’s extreme preoccupation with his healthisperhapsless than edifying, and the gluttony of DrGrant nothing shortof contemptible. But neither gentleman lays charges against her. Isit really worth coming to court for the sake of MissAusten’steasing?’

‘But—’ all six accusers rose protesting andLadyCatherine’svoicecarriedthroughthecourt.‘Donottriflewithus,sir.You would not say such things if you were a woman.’

With a sigh, he subsided, but no sooner had he leantbackthanJane found his colleague in the middle of the daisaddressingher. ‘Well, Miss Austen, you’ve heard the prosecution’s evidence. What have you tosay?’

These ladies – their bodies either stiff inside their corseting or else fleshy and sagging under their righteous fury – ought to make her laugh, not tremble, but when she rose to reply she found her knees were not quite steady and she had to grasp the dock’s wooden surround to stop her hands from twisting together in alarm. Taking a deep breath, she made herself speak slowly as though she werecalm.

‘Ladies, your indignation is great indeed. You accuse me of having defamed you. But I repudiate your charge. When I wrote Emma, did I not take my impetuous heroine to task for her thoughtless behaviour? When my Mr Knightley asserts that Miss Bates’s age and indigence should arouse Emma’s compassion, not her flippancy, do I not speak out on behalf of every old woman who has ever found herself a target for youth’s barbs?’

‘Not so, dear.’ Lady Russell had risen. ‘For the fact is, your creations enjoy a more vigorous life than the sentiments they utter. We all admire Mr Knightley’s integrity, but actions speak louder than words. In preparing to come to court, I had to remind myself of what he says that day on Box Hill. My memory requires no such prompting to recall how my friend Mrs Norris refuses to let Fanny have a fire to warm that chill East Room. Further, I cannot set eyes on a green baize surface without recalling Mrs Norris’s effrontery in appropriating the curtain intended for the Mansfield theatricals. You may claim that respect is our due, but so often you show us forfeiting it by our conduct.’

‘Is this assertion true even of Mrs Jennings?’ Despite the deep breaths, her question came out in a gasp.

‘Mrs Jennings who pours heartbroken Marianne Dashwood a glass of Constantia wine because it helps soothe colicky gout? Now really, that is as much a blending of the good and the ridiculous as anything you achieve with Miss Bates. Mrs Jennings doesn’t help you at all.’ Lady Russell’s voice became stern. ‘When, in the future,’ she asserted, ‘Mr D.W. Harding of London University will come to join us here, he will seek to convince you that in your heart you hated – his word, dear, not mine – your society and that in order to make your life bearable, you regulated your hatred by turning it to ridicule. Now, none of us much cares to be made to look ridiculous. That is why we press our charge and ask the judges of the dead to punish you by consigning your books, your letters and all evidence of your writing to Lethe. When everything is forgotten, we shall consider ourselves vindicated.

Forgotten? When those works were so dear to her? Even if she could not refute the charge, surely she might frame some plea in her own mitigation? If she might only return to earth once more, she would create an elderly woman who combined such benevolence and sagacity that the whole world would love her and long to be as old and as clever and as kind as she. Jane opened her mouth tospeak.

‘Silence,’ announced both the usher and the court clerk in the same second, and the judge at the left-hand end of the dais rose with upheldhand.

‘Before the bench pronounces judgement,’ he said, ‘it behoves us to consider our powers. To suppress these books through all eternity when they stand published by Mr John Murray in elegant demi-octavos and when some of them have attracted the favourable opinions of royalty, no less, is quite beyond our remit. The court’s learned advisers, Mesdames Clotho, Atropos and Lachesis, have already shown us future generations enjoying them. Sit down, please, Mrs Ferrars. Even the judges of the dead cannot fightfate.

‘But neither, prisoner in the dock, can we acquit you of the charge that Mrs Norris and her co-prosecutors bring. However we have, we believe, found a way forward. Your books, Miss Austen, shall be spared and read until the end of time.’

She closed her eyes inrelief.

‘But listen, young woman,’ the judicial voice went on, avuncular but resolute, ‘to our sentence. You have, throughout your life, maintained regular correspondence with your brother Vice-Admiral Sir Francis Austen, have you not?’

Frank? An Admiral? How wonderful!

But—

‘Yes, indeed, sir,’ was all she said.

The judgenodded.

‘Francis Austen we know to be fond of you. Throughout his earthly life – which will prove long – he will cherish every letter you ever wrotehim.’

Every letter? There must be hundreds. She had kept no journal, but her writings to Frank served a journal’s purpose. They held her innermostthoughts.

‘He will often re-read them to catch in their sentences the cadence of a favourite sister’svoice.’

At the thought of it, she wanted to laugh for pure pleasure.

‘He knows you opened your heart to him as you did to no other creature uponearth.’

It was true. The novels were witty in their way, butallherhappiest teases and shrewdest remarks lay in the letterstoFrank.‘Your confidences,’ the grave voice pronounced,‘willdelighthimallhisdaysandbringhimalittleconsolationforyourearlydeath. Further, he will harbour the hope that in timeyourletters’wisdom and shrewdness will reach and delight other readers too. But they never shall.’

Hepaused.

‘Francis Austen’s daughter, Fanny, shall burn them in bundles on her father’s death. With them will vanish a fair part of yourself, Miss Austen – perhaps the pithiest, most compassionate part; the part that speaks through Mr Knightley rather than Mrs Norris. But your books shall remain. You may stand down.’

At the time, the thought of all her exchanges with Frank passing into oblivion left her wretched. As she departed from the court, she had to steel herself not to cry. But in the fullness of eternity, she met her niece Fanny under the white cypresses surrounding the Elysian Fields. She recognised her at once.

‘What thought was in your mind,’ she asked, their greetings done, ‘when you destroyed my letters to your father?’

‘Oh,’ said Fanny, ‘did I really do that?’

She frowned, as though scouring her thoughts. At last she sighed and shook herhead.

‘When I arrived in this place,’ she said, ‘I was thirsty and they gave me water of Lethe to drink. It is extraordinary that I should even know who you are, Aunt Jane, for of my earthly life I can remembernothing.’

My inspiration: Jane Austen is strong on rebarbative women. I wanted to show them turning the tables on her, and had a suspicion that Mrs Norris would take the lead.

SECONDTHOUGHTS

Elsa A.Solender

SECOND THOUGHTS

Elsa A.Solender

She had said yes. Yes, I will. She had felt his hand briefly touch her shoulder; his lips lightly graze her check. When she opened her eyes, he had turned away. Had he any notion that she had avoided hiseyes?

Now all was settled between them. Watching him leave the room, she could read his satisfaction – his relief – in the spring of his step. Were he to leap up and click his heels together, she would not be entirely surprised, for he must be pleased that he had brought it off so well, as truly he had.

He was a stout young man turned twenty-one, just down from Oxford, wearing a striped silk waistcoat – a puce-and-purple striped waistcoat – poised to commence life as a gentleman of means, if not fashion. Was ‘poised’ the proper word? Was ‘poise’ indeed possible for Harris Bigg-Wither, a young man in a puce- and-purple striped silk waistcoat, and evidently in need of a wife, or persuaded that hewas?

And now promised a wife: yes, I will.

Did he truly know what he was letting himself in for, she wondered, by offering for Miss Jane Austen? Had he no notion of theglintofironylurkinginhereye,thesharpnessofthetongue disguised by the amiable, good-natured manners that she presented to the world? His sisters must have: they had known her forever. Alas, not even his sisters had seen the jottings that Cassandra – Cassandra alone – had read, the idle, wicked musings on the friends and neighbours whose antics she had observed with such shameful enjoyment and described with such relish to her sister. But he must know of the pages tucked into her writing slope which she sometimes read to friends, images of that other world that flashed in her restless brain, a world of handsome young men with clever conversation and fair young ladies who danced with them in The Dashing White Sergeant or the figures of another of the country dances that could so nicely set her free – briefly – of the conventions of hercompany.

She tried to recall dancing with Harris Bigg-Wither and could not.

It is done, she thought. No crying off.

Her poverty – this new sense of poverty since Papa had ceded his livings to brother James, this humiliating dependency upon the generosity and the whims of others – the indignities – the little slights – the necessary economies – all those would cease when she was Mrs Bigg-Wither, mistress of Manydown Park, an estate comparable – almost – to Godmersham, brother Edward’s principal seat. No longer Miss Jane Austen, a dowerless spinster of twenty-six, but Mrs Bigg-Wither, wife to a gentleman of means – seven thousand pounds a year! A considerable man, however young, however shy, however blank his eyes at times, a friend, an old friend, comfortable, with no meanness in him that she knew. The five years between them would be as nothing – had not brother Henry and cousin Eliza, fully ten years his senior, dealt happilytogether?

Had Harris attended to the passage she had read to the Manydown circle two nights before about the serious business of annuities? He had nodded, had he also smiled?