4,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Hesperus Press Ltd.

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

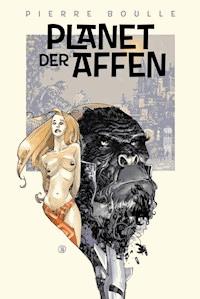

Long before The Hunger Games or Battle Royale, Pierre Boulle's darkly comic and twisted imagination came up with Desperate Games. Like his most famous masterpiece, The Planet of the Apes, Desperate Games is a dystopian sci-fi classic, imagining an alternate future where humans seal their own fate. Despairing at the state of world degeneration, a group of the world's most renowned intellectuals form the new Scientific World Government, aiming to put the world to rights. Elected into power, they quickly start making changes for the better, eliminating world hunger and cancer; encouraging scientific thought and banning frivolous entertainment. But while congratulating themselves on a job well done, they fail to notice that actually, people are not happy… The suicide rate has sky-rocketed and, strangely, it turns out the public want a little risk and conflict in their lives. So to cater for the masses, the Department of Psychology forms a plan. They will stage an entertainment show the likes of which the world has never seen before. It starts with gladiatorial style battles, bloodthirsty and brutal, where the victors become celebrities of unseen proportions, and quickly escalates into entire historical battle re-enactments involving chemical warfare and mass destruction. The Scientific World Government has unleashed a monster. What has the world let itself in for…?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Desperate Games

Pierre Boulle

Translated by David Carter

Contents

Part One

1.

There was a ringing sound. Having spent half an hour exchanging rather forced, joking remarks to calm their nerves, the candidates were now silent. In spite of their usual self-control, all of them had experienced the same emotion, the same beating of the heart. The heavy door of the institute was pushed open by an usher in his vestments. They followed him along a dark corridor and then entered the large amphitheatre where the examinations were to take place. There were thirteen of them, ranging in age from thirty-five to fifty.

Fawell was one of the first to enter the arena. Like the others, he was not carrying any documents or instruments. Logarithm tables and even simple calculation rules were prohibited. For this final examination they were only allowed to use the resources of their memory, their culture, their intelligence and their imagination.

This examination, or rather this competition, for it was a matter of selecting the best of the thirteen, was the final round in a serious assessment of their knowledge. It had been going on for three months and included an impressive series of tests, some of which had been eliminatory.

The candidates, who were numerous at the beginning, found themselves presented by turns with problems in higher mathematics, theoretical and experimental physics, chemistry, astronomy, astrophysics, cosmology and questions on diverse branches of biological sciences. In short an impressive range of subjects, requiring in-depth knowledge of the most noble and most diverse fields in which the human mind can be trained.

As the average level was very high (they all came from world-famous schools and many had already distinguished themselves with their important research or original theories), each of the examinations was fraught with difficulties. Not only did they require the solving of challenging problems, but they also demanded a considerable personal contribution, so much so that the compositions were of doctoral thesis standard. Thus they were authorised to make use, at their convenience, of all sorts of tables and calculating machines and could even use the Institute’s computers and consult all the works in the library, which contains almost all human knowledge. It was not a question in any way of cramming. The examination was conceived to emphasise genuine scientific knowledge. The subjects were established by an assembly comprising undisputed world authorities, known as the Nobels, that is to say those who had received the supreme recognition of being awarded the prize.

During the three long months of the preliminary examinations, the candidates remained cloistered in the Institute, with access to laboratories, computers and the library, but without any communication with the outside world and sleeping in cells which were monastic in appearance, constructed for this event in the same building.

The examiners were also Nobels. No one else could have replaced them in their functions, given the transcendant nature of the subjects chosen by them. They had judged without leniency, imbued with their immense sense of responsibility. The several thousand candidates who had presented themselves had seen their ranks thin out gradually. The first three compositions, those of mathematics, theoretical physics and chemistry had narrowed the field immediately: any candidate who did not attain the grade of sixteen was eliminated. This was the case for most of them. The rest, about a hundred, were subjected to all the following examinations, and were then given permission to leave the Institute, while the Nobel jury in its turn retired to a cell to discuss its verdicts.

The results of these debates were published a few days ago. Only thirteen were fortunate enough to qualify. This had been clear since the beginning of the competition, as there were only thirteen places. Fawell was among the chosen ones.

He reached the bench which had been assigned to him. His companions did the same and everyone sat down, silently awaiting the distribution of the envelopes containing the topics. The great amphitheatre, which could hold about a thousand people, seemed to him strangely empty. The thirteen survivors had been placed as far as possible from each other, not to avoid possible copying (the nature of the final examination made such actions pointless and the honesty of the candidates was not in doubt), but to allow them to concentrate. In fact Fawell felt this isolation weighing on his shoulders in an unpleasant way. In spite of his experience of innumerable examinations which he had passed before, and all brilliantly, he felt a sudden attack of nerves, the like of which he had not experienced since he was young. He observed his companions, trying to detect if they felt the same unease.

The two nearest to him were two friends of long standing: Yranne and Mrs Betty Han. They had attended the same university previously and had never lost contact with each other. Yranne was a pure mathematician, a Frenchman, who often stayed in the United States. Fawell, an American himself, called on his talents from time to time to resolve certain difficulties in calculation, which he happened to encounter in the course of his research. He always appreciated collaborating with Yranne due to his logical mind and the force of his deductions.

Fawell’s speciality was nuclear physics. On leaving university he had initially worked under the direction of one of the greatest masters, the Nobel called O’Kearn. Then, by his own efforts, he had got himself noticed by the academic world for his interesting discoveries concerning anti-particles. Like Yranne he was a little over forty, the average age for the competition. The regulations fixed strict limits for the candidates: thirty-five and fifty years. The tasks to be carried out by the thirteen chosen ones, and especially the final winner, were not compatible with being too young, nor with the sclerosis of extreme old age.

Mrs Betty Han, Betty to those who knew her intimately, was sitting on a lower tier. She was the only woman admitted to the final examination, which did not fail to give rise to several malicious remarks by the other candidates who had been eliminated. But there was scarcely any echo of such things here: the conscience and objectivity of the Nobel jury had never been generally in doubt. Fawell was happy and surprised to see her there because he had been afraid that she had been eliminated. He certainly considered her to be of superior intelligence, but mathematics and physics were not her speciality. Although she had started by undertaking serious scientific studies, she had abandoned them after passing the examinations with flying colours, in order to tackle other fields considered frivolous by certain scholars. Thus she had become infatuated with literature, only to turn soon after to philosophy. Finally she had devoted herself to psychology. She had gained significant honours in this field, but many of her former student friends joked with her about such decadent indulgence. That she had been successful in the pure science examinations, while the specialists had failed, was a new sign of her profound intelligence, and of her diligence too, for she had relearned long-forgotten subjects during the few weeks prior to the competition.

Fawell, who had helped her with his advice, was delighted at her success, for he himself did not despise psychology, and considered Betty’s presence among the thirteen to be desirable. When he congratulated her about it, she replied with a smile that her speciality had been useful to her, even for the examinations in mathematics, inspiring her to present her work in a way which would seduce a Nobel jury. Betty was Chinese, having long since separated from an American husband, but had kept her nationality, which had become possible since relations between the countries had been normalised. This imposed no obstacle to the friendly relations she maintained with the scientific world in the United States. In the circles of scholars in which men like Fawell and Yranne moved, questions of nationality, race and religion had lost all significance a long time ago.

Fawell, the father of a young girl of eighteen, had no objection to Ruth marrying a Russian, as she had confirmed her intention to do. Her beloved, Nicolas Zarratoff, was the son of a famous astronomer, whom she had got to know during a stay in the Soviet Union, where she was accompanying her father on the occasion of a conference. The physicist would have preferred a young scholar as a son-in-law, but Nicolas seemed to him to be a suitable match. At twenty-six years old he had already had quite a remarkable career in aviation. Having plunged himself recently into astronautics, a second still more brilliant career was opening before him. Moreover his father was a friend of Fawell, and he admired unreservedly the astronomer’s almost mystical passion for science. The parents had no objection whatsoever to their children’s plans. As Ruth was a little young however, they asked them to delay matters for a year or two to think things over.

Zarratoff Senior was also there in the amphitheatre. Turning his head, Fawell could see him perched on the highest tier. He smiled, thinking that it was no doubt a stroke of luck that the astronomer was in the position closest to the sky, the domain he was familiar with. The fact that he had reached the final thirteen had not surprised him, for, being a master of his special field, the Russian possessed extensive scientific knowledge and at the same time a fertile imagination.

It is amazing, the physicist thought with satisfaction, that all four of us have been selected: Betty, Yranne, Zarratoff and me. His own success did not surprise Fawell. He could make a fair evaluation of his own merits and knew that he could compete with the most eminent scholars of his generation for the extent of his knowledge and the keenness of his mind.

He didn’t know the other candidates as well. Among them were two biologists, a chemist and then mostly other physicists like himself. But there wasn’t time to try and read the feelings on their faces. Fawell looked forwards again, towards the masters’ platform, where an usher was introducing three members of the jury: three Nobels.

2.

The three illustrious scholars were also in their vestments. The first was none other than O’Kearn, the most senior member and the most famous of all the Nobels, and whose laboratory Fawell had been visiting for a long time. He was of a majestic appearance, which matched his reputation, and his eyes shone with an unusual brightness in a face marked with deep wrinkles by study and passionate research. A halo of white unmanageable hair suggested a vague resemblance to certain portraits of Einstein. He managed to accentuate the similarity by deliberately making his hair untidy.

When the members of the jury appeared, the thirteen candidates exchanged a furtive glance, and then stood up by common accord, as used to be the practice in the past in certain universities at the entrance of a famous master. Fawell could not prevent himself from smiling in noticing this reflex from their youth. The three scholars appeared to be flattered and O’Kearn made a benevolent gesture, indicating to them that they could sit down again. Then he raised an envelope above his head.

‘Madam, and gentlemen,’ he began, ‘here are the topics. I have ascertained, we have ascertained, my two colleagues and I, that the seal of the envelope is intact, and you can certainly do the same for yourself… In fact,’ he added, with a smile, ‘if there is anyone among you who nurtures the least doubt concerning this point, he can reassure himself by coming forward.’

A murmur of polite protestation greeted this taunt. No one would permit themselves to suspect the honesty of such a jury. Thus there was a murmur coloured by a nuance of surprise and even of disapproval when they saw Mrs Betty Han, doubtless the youngest of all the candidates, rise quietly and make her way with an assured step to the master’s chair. The two Nobels already seated raised their heads, also surprised by this gesture, while O’Kearn, who was standing, and still brandishing the envelope, watched her progress attentively. Betty did not become flustered, mounting the three steps and stopping in front of him. He held out the envelope towards her. She examined it carefully and then returned it to him.

‘Are you satisfied?’ the president of the jury asked.

‘It’s perfectly all right, Master.’

‘So you do not completely trust our word?’

‘Master,’ she replied calmly, ‘in circumstances as important as the present ones I do not trust anyone, not even the three Nobels.’

O’Kearn stared at her with increasing intensity, and then he shook his head. Fawell, who knew him well, interpreted this gesture as approbation. She was right, he thought. A good point in her favour.

Betty had gone back to her seat. In an almost religious silence O’Kearn unsealed the envelope and took the subjects out of it: there were sixteen copies, each containing only two pages. He gave one to each of his colleagues, keeping one for himself, and made a sign to the usher to distribute the rest to the candidates. When each of them had their copy, he cleared his throat and spoke in suitably solemn tones:

‘Madam, gentlemen,’ he said, ‘each of you is now in possession of the topics, or rather the topic, for it is unique, for this final competition. I shall read it to you. You are requested to follow it with the closest attention and to interrupt me if some point does not appear clear to you.’

He made a pause, while the candidates leaned over their papers, and he began:

‘“COMPETITION WITH THE AIM OF APPOINTING THE POST OF PRESIDENT OF THE SCIENTIFIC GOVERNMENT OF THE WORLD…”’

Here he interrupted his reading and made this comment:

‘Before coming to the topic itself, you are reminded at this point of the aim and terms of this test.

‘“…The candidates are reminded that this competition, the first of its kind, is open solely to the members already designated for a world government. These have been judged the most worthy to constitute this body as a result of an examination which has made it possible to evaluate the extent and quality of their knowledge of the principal matters concerning the future of our earth and of humanity.

‘“The specific goal of this final test is therefore to select that person among you who appears to be the best qualified to preside over the world government which has already been constituted.

‘“The candidate who, according to the jury of Nobels all present here, shall have provided the best work on the topic set out below, will, ipso facto, be entrusted with the duties of supreme leader.

‘“The candidate who, also according to the decisions without appeal of the same jury, shall have submitted the second best composition, will be elected vice-president and will be called upon to replace the first choice in case of the decease or incapacity of the latter.

‘“The other candidates will be appointed to different ministries, to be decided by the president. Each will be given a number however according to their ranking in the present competition, which will serve to determine the order of promotion to vice-president in the case of the decease or incapacity of the latter.

‘“The Scientific Government of the World, or SGW, will assume its functions immediately after the proclamation of the results. At that point the provisional administration conducted at the moment by the assembly of Nobels will cease to be. The present SGW will stay in place for nine full years, unless the opinion of an absolute majority of the Nobels is to the contrary. It will also have to make a presentation before them every time a decision of exceptional scope is envisaged and, in any case, at least once a year, for an inspection of its work.”’

O’Kearn interrupted his reading for a moment and lowered his paper.

‘Is this all clear?’

After receiving unanimous agreement, he continued:

‘Now here is the topic:

‘“The candidates should explain in broad outline what they consider to be the best programme for the nine years of their term of office, and the direction, impulse and priorities, etc., with which they will imbue this programme if they attain the post of president.

‘“Important note: This topic must of course be treated in a rigorously scientific spirit, but the candidates may, if they judge it useful, include certain extra-scientific considerations, such as the needs and aspirations of the working classes. No rule, nor rigid framework is imposed on them.”’

That was all. O’Kearn asked once more if this had been understood and if anyone had a question to ask. Then, looking at the electric clock, he said:

‘Fine. Madam, and gentlemen, the competition starts now. It is the 10th of May and it is ten minutes past nine. As your rule must last nine years, as you know, you have nine full days to write your compositions. On the 19th of May at ten minutes past nine your papers will be collected. I remind you that you have the right to make use of any document and I hope you feel inspired.’

Fawell waited quite a long while before deciding to write, looking at certain other candidates already leaning over their desks. He exchanged a friendly glance with Betty, and then with Yranne. They were also deep in thought, no doubt trying to concentrate before getting down to work. The feeling that there was some communion of minds with his friends gradually dissipated the tension which had been paralysing him since the start of the session. He now felt fresh and sure of himself.

He fixed his gaze on the platform where the three Nobels were conversing in low voices, against the backdrop of the busts of famous scholars, who had become the patrons of the scientific era, perched on their pedestals. At first only three busts had been thus arranged in the place of honour in the great amphitheatre: those of Galileo, Newton and Einstein. But this exclusive choice of physicists lead to lively protests on the part Nobel physiologists and it had become necessary to add to them the effigies of several great masters in their special field. But the physicists had however managed to arrange for the bust of Einstein to be placed in the centre and for his pedestal to be raised a little higher than those of the others.

In a more modest corner of the area one could also see a smiling portrait of citizen Garry Davis. He could not be ranked as highly as the scientific geniuses, but he had been one of the pioneers of the world government and it would have been a pity for him not to remembered here.

Without understanding especially why, Fawell smiled at them all and concentrated on his topic, confident of the outcome of the competition.

3.

The revolution of the ‘men of science’, or ‘the conspiracy of the Nobels’ as certain people sometimes called it (wrongly, because the initiative had not come from them), took on its precise form in California, amongst a small group of scholars, in an atomic city, which had been created around a giant betatron and several instruments of that kind, which were at the same time both monstrous and sensitive. Having gone there to pursue their research, which enabled them to penetrate a little further each day into the structure of matter, the physicists from all over the world liked to meet in the evening after work to compare their results with those of their colleagues, to discuss this or that theory or simply to exchange ideas in general. Most of the time these meetings were in small groups and had a truly international character. For several years Soviet and Asian scholars had been able to obtain permission to teach courses in the atomic city, and had developed the habit of doing so, conversing as freely as the others with the most qualified men of science of the New World and with the western world in general.

But if the idea arose and matured there, followed immediately by the will to action and to make a plan, it was only the culmination of a slow progression of the scientific mind, which had been happening in every country for a long time. In the course of their meetings and their conversations, which became more and more frequent, the scholars had come to regard themselves as having formed a truly international world organisation, and the only worthwhile one, that of knowledge and intelligence. Science was for them at the same time the soul of the world and the only force in a position to realise its destiny, after having rescued it from the trivial and infantile preoccupations of ignorant and long-winded politicians. Thus, in the course of numerous friendly discussions, which were almost fraternal, there had gradually developed the vision of a triumphant future, of a planet united, and finally governed by learning and wisdom. It was no longer a matter of confused views and imprecise aspirations. Those who tested the ideas out found them to be based on evidence and good sense, but they were a long way from being able to predict ways of putting them into practice.

The spark flared up almost simultaneously, however, in the brains of several relatively young scholars, invited to the bungalow where Fawell lived with his daughter. He had married quite young, but had lost his wife while Ruth was still a child, and becoming more and more absorbed in his research, he had never remarried. Ruth, who had no real taste for her studies but pursued them to please her father, ran the household, which was an easy job, given her father’s lack of concern about material matters.

A commonplace incident was the cause of the sudden explosion of minds: a television programme, which managed to unnerve some ordinarily calm colleagues invited to come and have a drink after a long day’s work. Several physicists of various nationalities were present, as well as the mathematician Yranne, who apart from his personal research (which he was able to pursue wherever he was, needing only a pencil and a sheet of paper), provided help to several others with his talent for analysis. Mrs Betty Han was also present. When staying in the region she never missed a chance to catch up with her friends.

After having refilled the glasses and confirmed that the guests’ favourite drinks were at hand, Ruth asked for permission to withdraw, foreseeing that there would be the usual discussions concerning work in progress. But these rather languished after she left and were soon abandoned. It seemed that all of them, without any mutual consultation, were prey to an idéefixe which distracted them that evening from their favourite topics. After glancing at his guests, Fawell switched on the television set. Everyone listened, glass in hand, and watched with curiosity, frowning and with tense expressions on their faces, which seemed to reflect a common feeling of exasperation. It was the usual interview, with a prominent politician giving his opinions with equal confidence on the country’s internal problems as on foreign affairs. It lasted a quarter of an hour. The comments struck Fawell as exceeding the bounds of stupidity, and noticing that his guests had the same feeling, he turned off the programme with a violent gesture and looked at his friends.

‘You heard it, just as I did,’ he said. ‘Every day it’s the same, more or less, with very few variations. The same nonsense churned out over the airwaves every day by men who imagine that they are actually running the country.’

An Englishman, who was teaching a course for several months at the betatron, interrupted him to reassure him that the same stupid things were common currency in the United Kingdom.

‘And I’ve heard even worse in France,’ confirmed Yranne.

An Italian declared that in his country the comments of politicians were no less childish than those which had just been heard. The same expressions, ‘unbearable’, and ‘intolerable’ were uttered in all corners of the room.

They had heard nothing more than the usual clichés and official or semi-official declarations. The average viewer would not have been offended. Normally they were not concerned very much about it themselves. But this evening all trace of resignation had disappeared. ‘It’s intolerable, you’re right,’ insisted Fawell, in an odd tone which made everyone focus their attention on him.

He remained silent for a moment, and then he continued, rapping out the syllables:

‘In-to-le-ra-ble, we all agree. Is there anyone who will contradict me if I affirm that that which is intolerable must not be tolerated?’

‘Certainly not me,’ said the mathematician Yranne.

‘It is therefore our duty to act –’

He was going to continue, when a new person burst into the room. His rapid entrance, with his hair in a mess, his clothes dishevelled, and in his pyjama jacket, would have surprised them, even among this circle of friends where any kind of ceremony was unknown, if it was not for the fact that it was the astronomer Zarratoff, who was at that time on a visit to the United States, and who had come to spend a few days at the house of Yranne, one of his best friends. He was known for his absent-mindedness, his sudden enthusiasms, the passion which he brought to his profession, a passion finding expression sometimes in lyrical outbursts, and his mastery of the game of chess. Of all enthusiasts, only Yranne was occasionally able to beat him.

‘What’s come over you?’ Fawell asked him without very much concern. ‘We were not expecting you this evening. Yranne told me that you were buried in your work. Please don’t consider that a reproach. On the contrary, you could not have come at a better moment.’

In fact Yranne had left the astronomer in his room, in his customary posture: deep in contemplation with a map of the heavens spread out before him, and only pausing to make some hurried notes combined with complex calculations. He knew his friend well enough to know that it was pointless suggesting some distraction when he was absorbed in that way. He had simply warned Fawell that they could not count on Zarratoff that evening.

‘Forgive me, said the astronomer, who seemed to have his mind elsewhere. I couldn’t stand it. I had to talk to someone. I fled my room… It’s the television.’

‘The television?’

He took a swig of alcohol which Fawell had just poured for him and explained.

‘In fact I was working, but it wasn’t going well. I felt myself trapped in a tissue of contradictions. It was then that, to rest my mind, I had the crazy idea of switching on the television set…’

‘I see,’ said Betty. ‘He must have seen the interview.’

‘Not the interview!’ protested Zarratoff. ‘What do you take me for? I’m very wary of such things. I changed the channel after the first few comments. I turned to channel number three. Are you with me?’

‘Well?’

‘Well? If you haven’t tried channel three, you obviously wouldn’t understand.’

‘What does it show?’

‘Games!’

‘Games?’

‘Games,’ the astronomer repeated in a plaintive voice.

‘I understand,’ murmured Yranne.

‘I do too,’ said Fawell. ‘I am, unfortunately, familiar with them!’

All the scholars shared the astronomer’s agitation and seemed to be sincere in feeling sorry for him, without it having been necessary to give them any explanation. He tried to do so however, in the same pathetic tone with which he might have asked heaven to bear witness to his misfortune.

‘Games, do you get it? Or what they call games! While there are doubtless thinking beings in the universe who are desperately calling us on an undetected wavelength, these people divide themselves into two groups of a dozen each and play at pulling the ends of a rope, to the applause of a delirious crowd. And when –’

‘That’s enough, old friend,’ said Yranne, interrupting him. ‘We told you that we’ve understood it all and that we share your indignation. So, in one word, what’s your conclusion? What do you think of it?’

‘Intolerable!’ yelled Zarratoff.

The guests burst out laughing.

‘So we are all agreed,’ concluded Fawell, ‘Calm down and finish your drink. You arrived just at the right moment.’

They brought him up to date with the project which was taking shape and the discussion continued.

4.

‘As I was saying,’ continued Fawell, ‘today it is our urgent duty to put a stop to this situation. We do not have the right to let the world go to ruin. In this country all men of science will agree with this.’

‘In France as well,’ declared Yranne, ‘I can guarantee it.’

‘And in England also,’ said the British man, ‘but will they be of the same opinion in the Soviet Union?’

Zarratoff made no hesitation in replying: ‘Only about thirty years ago, one would have hesitated to reply to that question. As you know, the fact of being regarded with suspicion by a part of the world, caused us to maintain a dangerous spirit of nationalism, with which even our greatest scholars were infected. Today, now that this mistrust appears to belong to the past, after we have confirmed, as you have done, the incompetence of our leaders, I can guarantee that it does not exist anymore, and that all the men of science who are worthy of the name are supporters of a rational world organisation. I would add that there is nothing surprising about it. Weren’t we the pioneers of internationalism?’

Everyone applauded his words. Without prior consultation they came to a common conclusion: at the current stage of evolution, a scientific government of the world had become a vital necessity for humanity. But objections did occur to them, as was natural for minds trained to analyse objectively all the data relating to a problem.

‘All the world’s scholars desire it. That’s fine,’ said Yranne, ‘but what about the peoples of the world? What about young people?’

‘Ruth would agree,’ asserted Fawell, ‘and all her friends as well.’

‘So would Nicolas,’ said Zarratoff, ‘we have often discussed it.’

‘Ruth and Nicolas may have been influenced by the intellectual milieu in which they have lived… But can we really be sure about all the scholars? The Chinese, for example?’

‘Betty, you can answer that one.’

‘I think I can reassure you on this point,’ said the Chinese woman, screwing up her eyes, so that her eyelids were stretched. ‘I meet the most eminent of my compatriots fairly often, and I have had the opportunity to sound out their opinions cautiously on the appropriateness of such a revolution, for your plan outlined this evening is not new to me. I have anticipated for a long time that you would be inevitably forced to take action some day. The result of my enquiries is that they all think the same as you do, that is to say that an international organisation is indispensable. This is not new, and they also think that the only viable plan is yours. It is their opinion too that the only central government capable of establishing itself and worthy of running the earth is a scientific government. Believe me, they have had enough, like you, of the childishness of their leaders. Stupidity is, I’m afraid, also international.’

‘I am delighted to hear you say such things. But what about the peoples? As a psychologist, what is your opinion on the matter? Will they accept this revolution?’

Mrs Betty Han took her time before replying, and she screwed up her eyes even more, which in her was a sign of intense thought.