8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Brandon

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Alice Taylor remembers her childhood home – the farm with all its tools and animals, the home with its equipment for living, its daily challenges, constant hard work, and its comforts too. She describes the huge open fireplace where all the cooking was done, where the big black kettle hung permanently from the crane over the flames; here the family sat in the evenings, talking, knitting, going over the events of the day, saying the rosary. She experienced the sow being brought indoors to have her precious brood of bonhams. She recalls the faithful, beloved horses and their wonderfully varied outfits – one set of tackle for each job they did on the farm; the ritual of lighting the oil lamps – from the fancy one in the parlour to the tiny one under the Sacred Heart picture; the excitement of threshing day and the satisfaction of a good harvest – the stations, the neighbours, and later the local dancehall and cinema. All the jobs and tools of a way of life long gone live on in the hearts of those who were formed by it. Here Alice Taylor celebrates them all with love. 'magical … reading the book, I felt a faint ache in my heart … I find myself longing for those days … it is essential reading.' Irish Independent

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Reviews

About And Time Stood Still

‘And Time Stood Still warmed my heart and reminded me of the value of family, friendship and community’

Irish Independent

‘in this book, Alice Taylor is singing my song’

Irish Independent

‘this book is a very practical one … written from the heart by a woman who like most of us will have experienced grief in all its forms during life’s journey’

Western People

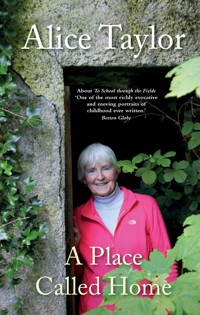

About The Gift of a Garden

‘poetical, beautifully descriptive … delightful read’

Country Gardener Magazine

‘definitely one to read with a cup of tea in your own garden’

The English Garden

‘will provide restful reflection for many’

Sunday Independent

Do You Remember?

Alice Taylor

photographs by Emma Byrne

Dedication

For my brother Tim, who was my inspiration and mentor, and for the ancestors who kept life flowing through the veins of rural Ireland

Contents

Introduction

The Memory Butterfly

In a long-forgotten garden at the back of all our minds are the faded flowers of a past season. These memory flowers are rooted into the fabric of our being where they sleep quietly beneath years of living. Then one day you hear a song on the radio or a special piece of music is played. Leafing through a book you come across the line of a poem you learned in school. On a garden visit an evocative scent wafts up your nose. You are searching for something in a drawer and an old photograph taken long ago with a brownie camera falls out.

And suddenly you are in another place. A memory butterfly awakens, gently flutters onto one of those faded flowers and gradually it comes to life. Wisps of memory begin to float around your mind and slowly come together. A faded scene forms and beckons you back to a long-forgotten place. As the vague picture begins to emerge you might turn hesitantly to a friend and tentatively ask, ‘Do you remember?’, or you might say to a person who has a different memory road, ‘Wait till I tell you how we did …’

As you journey back, it is wonderful to have a travelling companion. Maybe someone who has been there too and remembers, or a visitor to those times, someone new to your remembered way of life. You are on the remembering road and a companion is travelling back with you. Together you begin to fill in the missing bits of the jigsaw and explore long-forgotten things. There is a huge sense of satisfaction as the full picture begins to come alive. Sharing the experience is half the joy of travelling the Do You Remember road. And for those new to these long-gone times, having a guide who was there, who can draw you in as if you too were actually reliving these very experiences, is wonderful.

That is what this book is all about. My wish is to be a companion on your journey to other times and other ways, as I remember my home place, my grandmother’s dresser, the tea in the parlour, minding the chickens, or poems we learned at school. Clinging to the inside of all our minds like cream to the inside of a jug are the memories of our earliest years. We never quite forget them.

I hope you enjoy sharing these memories with me and that you relish the journey back along the memory road!

How nice to sit and think awhile

Of little things to make you smile

Of happy things you did in fun

Long ago when you were young

To think of people who were kind

And left a ray of light behind

People who were nice to know

When you were young long time ago

So come and sit with me awhile

And think of things to make us smile.

Chapter 1

The Home Place

It takes a lot of living to make a house a home. The living connects ancestry to posterity, creating a nucleus that supports and strengthens the extended family. Like a tree, families put down roots that give support and stability to extended branches. The home family provides a shelter belt and that sheltering can encompass the extended tribe when life gets stormy.

As we become teenagers and adults, many of us may develop a certain disdain for our parents’ way of life and discard many of their ideals. We may even revolt against them or indeed abandon their ways entirely, but as we mature we often discover the wisdom in some of the old ways and that we have something to learn from previous generations. Life has a strange way of opening our eyes to the value of things we once considered outdated. Seamus Heaney captured it beautifully when he said, ‘I learned that my local County Derry [childhood] experience, which I had considered to be archaic and irrelevant to the “modern world”, was to be trusted.’

Growing up in a home where eight generations of our family had lived I was made aware at an early age of the far-reaching influence of roots. During my childhood, people whose ancestors had been born in our house came back from all over the world to walk the land that had spawned their ancestors. It matters not whether your home place is a tiny cottage or a grand house its umbilical cord has the same pulling power.

Emigration was always part of Irish life and nowhere more than in the hilly regions of the Cork-Kerry border where I grew up and where wresting a living from the land had never been easy. Emigration was the answer to the problem. Young men from our area went mostly to Oregon and San Francisco, and to Australia, and the girls to Boston, New York and Chicago among other places. Some never came back, but generations later their descendants came to explore their roots. These people had grown up in the shadow of their parents’ and grandparents’ homeland and wanted to find out more about it. It was important then that the people in the home place gave them time, and that they sat down and told them about their ancestral roots. Sometimes these descendants had waited many years and travelled long distances to walk the fields where their parents or grandparents had played and worked as youngsters. Their parents and grandparents had often sent back hard-earned money to keep their home fires burning and their descendants now wanted to hear the stories of the home place which they had probably heard talked about since they were children.

I was amazed as a youngster to discover that deep in the marrow of human beings lies a strong need to connect with our life source – not unlike the salmon and the geese who each year instinctively travel across the world to come back to the birthing place of their ancestors. The laws of nature are beyond our human understanding.

And so, when the visitors came back to our home place long ago all work on the farm was suspended, which impressed me greatly. It could well have been a sunny day and we might have a field of hay mown and ready to be saved. Usually nothing – simply nothing – took precedence over this in my father’s world. After all, this was our bread and butter! But, prompted by my mother who treasured family history, my father put the returning descendants before saving the hay. His action spoke louder than any words. At the time we had an old man working with us who constantly reminded my mother that ‘Children have only what they see’, and later in life a nun at school told us ‘Sound is heard but example thunders’ – and it’s true! My parents were laying the foundation of deep respect for family. I was very impressed.

These visitors got tea in the parlour and sometimes their unannounced arrival meant that one of us young ones had to run all the way into town, which was almost three miles away, to bring back those little extras that my mother felt were necessary for her guests. Though often these niceties were left untouched and my mother’s brown bread was what was most appreciated. If she happened to have one of her homemade apple cakes on hand, this was especially savoured with delight – though my mother’s delight that we did not already have her apple cake scoffed was far greater than the visitors’ appreciation. Niceties in our house had to be kept under lock and key. The parlour table was set with my mother’s best tablecloth. Tablecloths at the time were made of pure linen or damask and had to be hand-washed, starched and ironed, and when one was spread out over the large parlour table it breathed ‘special occasion’. Then out came her best china and bone-handled cutlery and the ‘loaf sugar’, or sugar lumps, also kept securely locked away in her deep press beside the fireplace. All this fuss told us that these were special people who were to be welcomed back to their home place with proper ceremony. These returning emigrants also made us aware that we were simply custodians of our land, guarding it for all generations.

When I, like others, left the shelter of the home I took with me a deep love of my home place, and whenever in later life I hit a rough patch, my best therapy was to go back and walk those fields or to call a sibling, or a member of the extended family, or an old neighbour and talk over the problem with them. I became very grateful for the influence of my roots, and that included my grandmother, aunts, uncles and neighbours. It takes a whole neighbourhood to rear a child.

A few days after my father’s funeral the awareness of place really sank home. I walked with my brother down through the fields that our father had worked all his life to the river where he had fished. His spirit walked with us. We stood and watched the river he had loved and cared for flow silently by. On a regular basis he had checked its water for cattle pollution, making sure that nothing entered it to interfere with its fish or bird life. His belief was: wrong nature and you pay a terrible price. There was healing that day in gazing at the water of the river flowing by; an awareness as well of how transient life is and the timelessness of that river and the land of our ancestors that it flowed through. From them we had inherited not only the land but also an appreciation of the gift of life.

By a strange coincidence, the day I finished this chapter I received the following letter in the post which echoed exactly what I was thinking and it stayed with me for days. Here’s a short extract:

Dear Alice, I must write and let you know how much I’ve enjoyed your book Gift of a Garden. The garden gives so much back. To read about Uncle Jacky and to have the fun of continuing on his pleasure of gardening in his garden is extra joy. If it was anywhere else it wouldn’t feel the same. The feeling of belonging, of ownership, or perhaps not ownership – we tend to take care of what’s left to us and perhaps when we are gone a little bit of us remains, as Uncle Jacky still remains.

I was born and raised in Dublin. My mother’s parents came from Co Carlow. Her parents moved to Dublin but her grandparents and great-grandparents all came from the one little spot. My great-great-grandparents were stonemasons and I was told they built the house and surrounding walls. My mother holidayed every year when we were young down there and what freedom – and such wonderful people. It left a mark on me. They say it gets into your blood. I’d say it’s leaded into my marrow.

I have been very lucky to have been given a chance to buy a part of the land down there and to own the remains of a dry-stone cottage where my grandfather and great-grandfather were born. I feel a piece of land gives off its treasures. It can absorb a lot of us back into the soil, to join others gone before us. There’s only four walls and a chimney stack left, but what a wonderful thing to come my way. To walk on the same land that they walked on … I hope you don’t mind me writing to you. I feel you may understand the wonder of it all.

The Brook

Alfred Tennyson

…I chatter, chatter, as I flow

To join the brimming river,

For men may come and men may go,

But I go on forever.

I wind about, and in and out,

With here a blossom sailing,

And here and there a lusty trout,

And here and there a grayling.

And here and there a foamy flake

Upon me, as I travel

With many a silvery water-break

Above the golden gravel,

And draw them all along, and flow

To join the brimming river,

For men may come and men may go,

But I go on forever…

Chapter 2

The Woman of the House

The kitchen was the hub of the home. It was the cooking zone, bakery, laundry, dining room and at night a social centre, school room and prayer room. And if my mother had bought a roll of material in Denny Ben’s draper’s shop in town the previous Sunday to make what she called ‘up and down’ dresses for us, it became a sewing room – as you can gather from the term ‘up and down’ we were not exactly icons of fashion! My mother’s was the only sewing machine in the townland so other women came to do their sewing in the kitchen as well. When the hosting of the Stations came around it was a temporary chapel and when valuable eggs had to be hatched it became a hatchery. When the door was open in summer the hens, who were free-range in every sense of the word, felt quite entitled to wander in and help themselves to the crumbs that had fallen from the table. If it was deemed necessary to bring mother pig in to have her young, it became a delivery ward. When it incorporated a settle it could also be turned into a temporary hostel for an unexpected caller. All human and animal life on the farm revolved around the kitchen.

All farm kitchens were more or less the same. As well as being the largest room in the house, it was also the only one heated by the open fire that stretched across one end wall. A long press or dresser for holding ware stood across the other end. Originally – before my time – the floor was mud or cobbled, which was impossible to keep clean, and later concrete or quarry tiles were put down as they were able to withstand all the assaults of family and animal life. The ceiling was of slatted ceiling laths that sometimes, due to darkening by smoke, had to be scrubbed and repainted, and then varnished, turning the artist into an upside-down painter like a kind of Michelangelo! The finish of paint at the time was dull and flat, hence the need for varnish to give it a gloss finish. The lower half of the kitchen wall was cased over with timber, which we called ‘the partition’, but was in fact wainscotting. This was either stained and varnished, or painted and varnished. The paint was usually cream coloured or a pale green, depending on the taste of the woman of the house. The paint manufacturers at the time were Harringtons, and later Uno. The wall above the wainscotting was distempered. Hall’s distemper came in powder form and water was added until it arrived at a creamy consistency that was easy to apply. It had a limited colour range, but some colours were actually quite vibrant. Popular at the time was yellow ochre and my grandmother used this to paint the outside walls of her thatched house.