Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Brandon

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

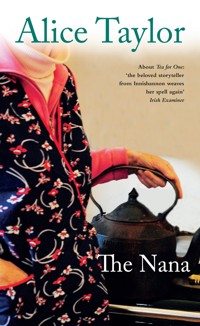

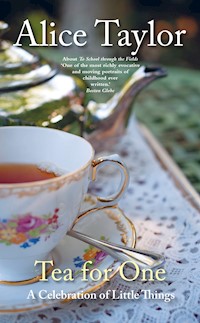

In Tea for One, Alice Taylor celebrates the little moments that bring us joy After many busy years raising a family and running a business, Alice is now living alone – with all the challenges and pleasures that brings. From improving her painting to perfecting her garden, exploring family histories and reclaiming her mother's art of tea-making, Alice celebrates the small acts that fill her days and make her happy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 211

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘A Gaggle of Geese’, by Alice Taylor

About Alice Taylor:

‘one of our best-loved writers ... encourages us all to treasure what we have’ RTE1’s Today Show

‘much-loved Irish author’ Belfast Telegraph

‘one of the country’s most accomplished storytellers’Irish Mail on Sunday

‘Ireland’s Laurie Lee’The Observer

‘...Taylor’s remarkable gift of elevating the ordinary to something special, something poetic ...’ Irish Independent

For more books by Alice Taylor, see www.obrien.ie

Dedication

To Fr Denis, who brings grace and blessings into so many lives

Contents

Learning from the Elders

We first witness the realities of growing older through our grandparents and then our parents. We also learn as we see elderly family, friends and neighbours come to terms with it.

Then it is our turn. Life turns full circle. I am now very grateful to these family elders and also to a retired lady who in her later years came to stay with us and was an example of how to handle the oncoming tide of years as she skilfully manipulated her boat through the challenging, choppy waters.

To all these mentors I am very grateful as they taught me many things.

As Time Goes By

Grow old along with me,

The best is yet to be,

The last of life for which the first was made …

Robert Browning

My early years in Innishannon were a whirlwind. Surrounded by small children, running a guest house, post office and a busy shop, sometimes with much-loved elderly relatives on board, the days were a stampede of non-stop activity. My wonderful husband Gabriel began work at 6am and often balanced the books in the small hours, while at the same time being part of every parish organisation. He kept so many balls in the air that one got dizzy just looking on. We also seemed to be endlessly building and extending the business, and the bank manager was forever threatening to pull the mat from under us so we were constantly over-stretched and stressed.

Sometimes, back then, I would dream of a day away from it all on a desert island where one could only hear ‘lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore’ … and then a waiter would magically appear bearing a tray laden with the 12most gorgeous food, and whip out a starched white linen tablecloth and arrange everything on a low table beside me, and then disappear into the mist. Later, sipping a Gaelic coffee, I would watch the moon rise.

Or I might dream of a day child-free and money-rich when I would drift through exclusive shops, spoilt for choice, and at midday take time out to dine in a top-class restaurant and enjoy the most delicious lunch, finishing up (again) with a Gaelic coffee (I had just mastered the art of making these, following a recipe on a tea-towel bought in a little shop down our street; Gaelic coffee signified real luxury for me back then). I wonder had GB Shaw the likes of me in mind when he wrote: ‘Youth is wasted on the young.’

During those frantic times an older lady came to stay with us – or, rather, moved into a tiny upstairs apartment which we had ironically christened the ‘West Wing’. She was very elderly (at least to me at the time) and so very posh that we never got to first-name terms; such a thing would be akin to calling the Queen of England ‘Lizzy’ , and such familiarity could not be condoned. Anyway, her name was unpronounceable to me, so she became Mrs C, though it might more appropriately have been Lady C as she had originated in an aristocratic rookery in the West of Ireland. Having lived a varied and interesting life all over the world, she was a wise old owl and I learned a lot from her, though at first I wondered how she came to be slumming it with the likes of us. ‘The old should surround themselves with 13the young,’ she informed me, which explained why she had landed herself in our midst.

One day I was running up the stairs dragging a basket of laundry with me while she waited at the top, leaning on her black ebony walking stick before beginning her painfully slow descent. On my arrival at the top she imperiously instructed, in her impeccable Anglo-Irish accent, ‘Alice, my dear, don’t ever grow old. It’s an appalling condition!’

To me at the time her conditions didn’t look half bad! She had successfully mastered the art of making the most of her life, which undoubtedly was now very different to what she had been accustomed to. Choice pieces of her family’s heirlooms had accompanied her into the West Wing, and a Jack Yeats masterpiece, gifted by the artist himself, graced her wall. She regularly wined, dined and played bridge with like-minded friends, while a whiff of cigar smoke and brandy wafted along the corridor and downstairs to us below. At Christmas she went to Harrods to do her shopping. Not a bad life in any man’s language. Certainly not to me at that time.

But now when I wake up in the morning, checking if all my parts are still functioning and capable of getting me onto the floor, and then how fast they will get me to my required destination, at the same time steadying myself in case I go head first into that destination – then I remember her. On top of the same stairs when I grasp the hand-rail and steady my pace to carefully make my way down in the hope of a safe landing – then I remember, and agree with her. And 14now in the garden when attempting to lift a heavy pot and my back tells my head that that I have stooped too low – then I remember and salute her. Despite her opinion that old age was appalling, she nevertheless had nurtured the art of coping admirably with it. And though unaware of it at the time, I learned a lot from her. As an old nun at school used to tell us: ‘Sound is heard, but example thunders.’

At that time, Gabriel and I loved to dance and, on hearing a favourite tune on the radio, would take off in an energising quick-step around the kitchen table. Now I grasp the brush handle and do a graceful glide into a slow waltz. My pace has certainly slowed down as life changed over the years, from being part of a large family, to half of a couple, and now a solo player.

Some people are home alone by choice, while others, like myself, evolved into it through a change of circumstances. But no matter how it comes about, living alone has its minuses and its pluses, and as the years go by you strive to get the balance right. You slowly grow accustomed to being on your own and you adjust to enjoying your own company and keeping yourself pleasantly occupied.

And then, to really test our mettle and coping skills, along came Covid-19, creeping in like a thief in the night and challenging medical expertise, the world economy, and the resilience of us all. At first we thought that it would be short-term and that soon all would be well again. But then the realisation slowly dawned that this was not just a skirmish but a war, and that we could not afford to get battle-weary 15because this silent enemy was deadly and persistent, so we would all have to dig deep and nurture long-term coping strategies and greater resilience.

Normally, living alone can be challenging, but there is a much deeper aloneness with Covid as it has cut away our social fabric, and you really miss pleasant outings and the company of friends, and neighbours popping in and out. And in this new aloneness you are more aware too that this is not the time to slip on a banana skin or topple off a step-ladder and end up in A&E. Because not only might there be nobody around to pick up the pieces, there might be nobody around either to provide transport in the event of such a calamity. And hospital was not exactly the place you wanted to be in these times, and, to put the tin hat on it, if you did finish up there you could be isolated for your own safety and not see the familiar face of a visitor for your entire stay. This alerts you to a new need to be more careful in case you come a cropper.

I remember Mrs C more often now and think how wise she was to move in with us because the young certainly do energise and entertain. She invited our children up to her West Wing (at specified times) to teach them how to play bridge and to put manners on them. I wonder how she would have coped with the different lockdown levels which we seem to be in and out of now like the cuckoo in a cuckoo clock. Pretty well, one would imagine. She was very resourceful and not into complaining. She had the resilience of one who had experienced the ups and downs of life, 16and she was certainly not obsessed with her own pains and aches, though undoubtedly at her age they must have been part of the package. One day when I enquired why she never complained, she told me, ‘My mother gave me one very valuable bit of advice: “Gundred, she told me, never complain, it destroys yourself and annihilates people.”’ So she never did. She kept herself well occupied and mentally alert with reading, doing crosswords, watching and listening to all kinds of sports on radio and TV, reading The Times daily and keeping up-to-date with world events, and she also had a great interest in what was going on locally, even in the smallest details. One evening as we chatted while looking down at the pub across the road, an elderly lady and her slightly doddery male companion went in and would be there, we knew, until well after closing time. This odd couple had recently moved in together, which caused Mrs C to wryly comment, ‘What a strange relationship that is, I doubt that she has him for his sexual prowess.’ She had a wicked sense of humour and would often articulate something that one might be thinking but would not like to verbalise. She always wanted to know what was going on downstairs and in the village. And every night before retiring she indulged herself and enjoyed a large hot whiskey.

The monks living in isolation on Skellig Michael, who have always fascinated me, had no such comforts and one would have to wonder how on earth they survived in that bleak, lonely, desolate place with none of the comforts of life that we have. Did isolation unearth and release creativity 17and resilience? Could that resilience and creativity lie deep down in the unplumbed depths of us all, I wonder? Is there something to be learned from this strange, weird world into which we had all been thrust? At my stage of life I thought that I had seen it all, but this was a whole new sobering experience. And then, on my eighty-third birthday came a card from my daughter of a formidable-looking lady wearing a ‘don’t mess with me expression’ and arms purposefully folded across a well upholstered bosom, with a quote beneath it from the legendary Bette Davis: ‘Old age ain’t no place for sissies.’ Could this isolation as well as the ageing process be a learning curve?

What I began to learn was that the strategies needed to cope with the isolation of Covid-19 and those needed to cope with living alone and growing older are often fairly similar – being absorbed in doing: painting, reading, creating, gardening and so on. When you no longer run a family or a business or go out to work, these enjoyable pursuits can become your focus. And isn’t it great to have the time to savour them?

Maybe now too could be the time to remember a poem that was in my mind of a long-held belief that slowing down and living in harmony with nature enriches your life. This awareness was seeded during childhood on the home farm, and over the years grew with me. Then very early one morning, while sitting alone in my sister’s wild garden in Toronto watching the sun rise and listening to the dawn chorus, the poem sprouted in my mind – probably triggered 18by the magic of the sunrise and the birdsong but also by a childhood image of going out in the early-morning dew to round up the cows for milking. The cows at that time of the morning were all lying down around the field, peacefully chewing the cud and they had no wish to be disturbed from their bovine meditation. Cows have no concept of hurry and will never engage in it unless stampeded into it by us hurrying humans, and even then it is totally unacceptable to them as their body is not designed for speed. So their first reaction on being alerted to the prospect of disturbing themselves is to slowly ease into their own body and check out their readiness to cope with any proposed movement. Cows are full of awareness, and are in complete harmony with the sun as it slowly rises above the horizon alerting the birds then one bird awakens with a faint twitter and very gently others join in, and slowly the volume rises until finally the whole chorus are all in full song. But this is all done slowly and gently. Nature can teach us so much.

Unfold Me Gently

Unfold me gently

Into this new day,

As the sun slowly

Edges the horizon

Before bursting into

A dazzling dawn;

As the birds softly 19

Welcome the light

Before breaking into

A full dawn chorus;

As the cow rises

And stretches into

Her own full body

Before bellowing

To her companions –

May I too slowly absorb,

Be calmed and centred

By the unfolding depths

Of this bright new day

So that my inner being

Will dance in harmony

With whatever

It may bring.

Solitude…

When you live on your own you savour precious moments.

And you select projects and occupations that you find truly absorbing, activities that for years you may have put on hold, like writing, painting, reading and gardening.

You also have the time to improve your ability to do things at which you were previously not very good.

For years I had envied good gardeners, artists and knitters, and now I am attempting to improve at all these absorbing hobbies. Learning new skills is also a challenge. For someone interested in wildlife and gardening, for example, perfecting the arts of photography or flower arranging can be uplifting and engaging experiences.

All these activities help to keep the mind exercised and alive.

Let’s Have a Cup of Tea

A re-awakening had taken place! A discerning friend brought me a packet of loose tea from Bally maloe. But I was so carried away with the other item in the packet that she was long gone before I became aware of the little cellophane-wrapped bag of black tea. My mind had been totally focused on the pot of Ballymaloe raspberry jam. Knowing from experience how wonderful this raspberry jam was, the very sight of it stimulated my taste buds. This jam deserved an appreciative reception. So it was first held up to the light of the window to better admire its depth and richness of colour. The contents were the final crescendo of a fruit harvest that had absorbed the warmth of the sun, the kiss of the rain, the touch of the buzzing bees and the softness of balmy country air – and all that goodness was now resting in this potful of glowing raspberries. My much-appreciated pot of jam was placed lovingly on the dresser shelf from where its deep glow enhanced the colour palette of its surroundings.

When I had finally finished paying homage to the jam, my eye fell on the little bag of tea proclaiming itself to be 23Ballymaloe Morning Tea. Broody, black and full of hidden eastern mystery, this little bag of loose tea had found its way unknowingly into dangerously unappreciative territory. Because this house is common tea-bag terrain.

Though reared by a mother who created a ritual out of tea making, I had become a lapsed tea maker. My mother’s self-appointed standards never varied and she refused to make tea from any kettle that she herself had not seen come to the boil. Her scalding of the teapot was akin to the preparation of a connoisseur’s glass about to receive priceless hot port. Her exactitude about measuring the tea was the result of years dedicated to her art. She was hailed within our family circle as having the skill of making THE perfect cup of tea. But not so her daughter! Not so! At least, not this daughter. Oh, how the mighty had fallen.

But could all this be about to change? As I stood silently gazing at this bag of dark, loose tea, son Number 2 put his head in the door at the other end of the kitchen and looked at my bag of Morning Tea in surprise.

‘Well, now, what’s all this about?’ he enquired in a puzzled voice. ‘Are you going back to making real tea?’

‘Not sure,’ I told him hesitantly, ‘but isn’t there something nice about the look of this bag of loose tea?’

‘Why did you change to tea bags in the first place?’ he asked curiously. ‘Nana would never have used tea bags.’

‘Convenience, I suppose,’ I admitted reluctantly.

‘But what was more convenient about tea bags?’ he questioned. 25

‘No tea leaves, I suppose.’ I was remembering out loud rather than answering his question.

‘But what’s wrong with tea leaves?’ he queried.

‘I suppose they were a bit of a nuisance in the sink,’ I admitted.

‘Interesting,’ he concluded, and that I assumed was the end of that.

But the following evening he arrived in with a small teapot fitted inside with a little porous basket called an infuser into which you put your tea leaves, and after partaking of the tea you simply lifted out this little infuser and up-ended the contents into the compost bin. Impressive! All of a sudden I was on the road to Damascus. I, who had been a lost soul to proper tea-making, was about to rejoin the fold.

But the return of this prodigal daughter necessitated some changes in the culinary department. Loose tea requires a caddy and this special tea required a classy caddy, and at first I thought that I had none to qualify for the position. Then my eye fell on the answer. On my dresser shelf was a heavy, chunky, navy-blue jar with ‘Harrods Food Halls’ inscribed in gold calligraphy across its chest. It was a gift from a friend who had visited that elite establishment and had brought me back this jar filled with coffee, and when the contents were consumed, the jar, with its elegant appearance and firm clasp, was too gorgeous be disposed of, so it got a home on the dresser. Empty and useless, but beautiful. A hoarder’s temptation. But now, at last, its hour had come. My hoarding was about to be justified. This jar would make the ideal 26caddy for my precious tea. Now, before you say it, I know that a jar is not exactly a tea caddy, but this jar was so beautiful and its genealogy so impressive, and the friend who gave it to me so special, that all these credentials qualified it for the caddy position. The next step was a suitable spoon to dispense the tea from this posh jar into my precious pot. And I had the perfect one. Buried amongst the cutlery in the dresser drawer, and also buried in my mental memory drawer, was a silver egg spoon inherited from my mother. It would be the ideal measure and it fitted perfectly into the jar. Now, we know that an egg spoon is not a teaspoon, but it somehow seemed right that my tea-making mother should have an input into these proceedings.

27And so, the following morning, for the first time in years, it was back to proper tea. The quality of the tea pouring from my dinky little teapot had a rich, amber glow that I had not seen for a long time. The flavour of my mother’s tea was back. Unwittingly over the years, I had cast her expertise aside.

Full of enthusiasm I rang my sister, who had never deviated from tea leaves, to tell her about my re-awakening. ‘I was wondering when you would cop yourself on,’ she told me unceremoniously.

That afternoon I retrieved some scones from the freezer and popped them into the Aga where they heated back to life while I made tea, adhering to all my mother’s well-remembered guidelines. Then I set the tea tray with my best china and carried it out into the garden where I savoured 28my scones, laden with the gorgeous raspberry jam and accompanied by a perfect cup of tea. My mother’s art of tea making had been redeemed and reclaimed. Tea leaves were now back in my life, thanks to my friend, Ide, and to Bally-maloe. A reawakening had taken place.

But a further embellishment to this rediscovered delight was about to be added. A friend, on hearing of my recent acquisition, produced a gorgeous little rich-red knitted tea cosy with a dark green tassel on top, which, when turned inside out, became a silver tea cosy with a smart red bow on top.

This tea cosy was made by an amazing young woman who was born into a resourceful farming family and who, despite being visually impaired since childhood, has mastered an incredible number of life skills. Years previously her creative grandmother and I had painted together and her gifted mother’s poems make inspirational reading. So my tea cosy came with an enriching family story attached, which made it very special.

All this caused me to question what other pleasant practices I may have unwittingly abandoned, leaking away life’s simple pleasures. Was now the time to revisit some of these enriching rituals that fast-forward living had obliterated?

The Gift of a Book

‘Through a chink too wide there comes in no wonder,’ wrote the poet Patrick Kavanagh. The stony grey fields of his small Monaghan farm crucified the poet, and yet inspired him to pen some of his most memorable works. To escape the drudgery of this hard farm life he went further afield and maybe felt that in the larger spectrum he lost some of his wonder. There’s a saying in Irish that my husband often quoted: An rud is anamh is iontach, meaning the rare thing is the most wondrous thing. And my grandmother used to tell us ‘What’s scarce is wonderful.’ So, following that logic, when, for social and economic reasons, books were a scarce commodity in the farmhouses of rural Ireland in the 1940s and 1950s, they were held in the highest esteem. For that reason too, a faded, green hardback copy of Oliver Twist, which happened to be in our house, was repeatedly read, and even our schoolbooks were treasured. Any publications coming into the house, such as Ireland’s Own and the Reader’s Digest, were absorbed in their entirety and deeply appreciated. And when the County Council opened a library in our town it was like manna in the desert, and then a rare visit to Cork city revealed a display of Emily Brontë and Jane Austen books in Woolworths, each for the 30princely sum of one shilling and six pence. This brought paradise within reach.

31