1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

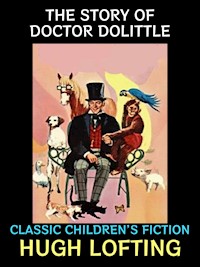

In "Doctor Dolittle in the Moon," Hugh Lofting ventures into a realm of whimsical imagination, where the beloved character, Doctor Dolittle, embarks on an interstellar journey to the Moon. The narrative is characterized by Lofting's unique blend of fanciful storytelling and charming animal characters, reflecting the early 20th century'Äôs fascination with space exploration. The book is infused with humor and moral undertones, as Dolittle'Äôs quest is not merely to explore new worlds but to advocate for the well-being of all creatures, making it a poignant reflection on humanity'Äôs role in the universe. Hugh Lofting, an English author and illustrator, created the Doctor Dolittle series after his own experiences in World War I and a desire to escape into the fantastical. His background in engineering and love for animals greatly influenced his writing, allowing him to craft a narrative that combines science fiction with a strong sense of empathy. Lofting'Äôs works often champion animal rights and environmentalism, themes that resonate powerfully in this moonlit adventure. "Doctor Dolittle in the Moon" is highly recommended for readers of all ages, inviting them to immerse themselves in a world where imagination knows no bounds. Lofting's enchanting prose and rich, playful illustrations create a delightful reading experience. This book encourages exploration and compassion, leaving readers with a profound respect for both nature and the cosmos.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

Doctor Dolittle in the Moon

Table of Contents

1. WE LAND UPON A NEW WORLD

In writing the story of our adventures in the Moon I, Thomas Stubbins, secretary to John Dolittle, M.D. (and son of Jacob Stubbins, the cobbler of Puddleby-on-the-Marsh), find myself greatly puzzled. It is not an easy task, remembering day by day and hour by hour those crowded and exciting weeks. It is true I made many notes for the Doctor, books full of them. But that information was nearly all of a highly scientific kind. And I feel that I should tell the story here not for the scientist so much as for the general reader. And it is in that I am perplexed.

For the story could be told in many ways. People are so different in what they want to know about a voyage. I had thought at one time that Jip could help me; and after reading him some chapters as I had first set them down I asked for his opinion. I discovered he was mostly interested in whether we had seen any rats in the Moon. I found I could not tell him. I didn't remember seeing any; and yet I am sure there must have been some—or some sort of creature like a rat.

Then I asked Gub-Gub. And what he was chiefly concerned to hear was the kind of vegetables we had fed on. (Dab-Dab snorted at me for my pains and said I should have known better than to ask him.) I tried my mother. She wanted to know how we had managed when our underwear wore out—and a whole lot of other matters about our living conditions, hardly any of which I could answer. Next I went to Matthew Mugg. And the things he wanted to learn were worse than either my mother's or Jip's: Were there any shops in the Moon? What were the dogs and cats like? The good Cats'-meat-Man seemed to have imagined it a place not very different from Puddleby or the East End of London.

No, trying to get at what most people wanted to read concerning the Moon did not bring me much profit. I couldn't seem to tell them any of the things they were most anxious to know. It reminded me of the first time I had come to the Doctor's house, hoping to be hired as his assistant, and dear old Polynesia the parrot had questioned me. "Are you a good noticer?" she had asked. I had always thought I was—pretty good, anyhow. But now I felt I had been a very poor noticer. For it seemed I hadn't noticed any of the things I should have done to make the story of our voyage interesting to the ordinary public.

The trouble was of course attention. Human attention is like butter: you can only spread it so thin and no thinner. If you try to spread it over too many things at once you just don't remember them. And certainly during all our waking hours upon the Moon there was so much for our ears and eyes and minds to take in it is a wonder, I often think, that any clear memories at all remain.

The one who could have been of most help to me in writing my impressions of the Moon was Jamaro Bumblelily, the giant moth who carried us there. But as he was nowhere near me when I set to work upon this book I decided I had better not consider the particular wishes of Jip, Gub-Gub, my mother, Matthew or any one else, but set the story down in my own way. Clearly the tale must be in any case an imperfect, incomplete one. And the only thing to do is to go forward with it, step by step, to the best of my recollection, from where the great insect hovered, with our beating hearts pressed close against his broad back, over the near and glowing landscape of the Moon.

Any one could tell that the moth knew every detail of the country we were landing in. Planing, circling and diving, he brought his wide-winged body very deliberately down towards a little valley fenced in with hills. The bottom of this, I saw as we drew nearer, was level, sandy and dry.

The hills struck one at once as unusual. In fact all the mountains as well (for much greater heights could presently be seen towering away in the dim greenish light behind the nearer, lower ranges) had one peculiarity. The tops seemed to be cut off and cup-like. The Doctor afterwards explained to me that they were extinct volcanoes. Nearly all these peaks had once belched fire and molten lava but were now cold and dead. Some had been fretted and worn by winds and weather and time into quite curious shapes; and yet others had been filled up or half buried by drifting sand so that they had nearly lost the appearance of volcanoes. I was reminded of "The Whispering Rocks" which we had seen in Spidermonkey Island. And though this scene was different in many things, no one who had ever looked upon a volcanic landscape before could have mistaken it for anything else.

The little valley, long and narrow, which we were apparently making for did not show many signs of life, vegetable or animal. But we were not disturbed by that. At least the Doctor wasn't. He had seen a tree and he was satisfied that before long he would find water, vegetation and creatures.

At last when the moth had dropped within twenty feet of the ground he spread his wings motionless and like a great kite gently touched the sand, in hops at first, then ran a little, braced himself and came to a standstill.

We had landed on the Moon!

By this time we had had a chance to get a little more used to the new air. But before we made any attempt to "go ashore" the Doctor thought it best to ask our gallant steed to stay where he was a while, so that we could still further accustom ourselves to the new atmosphere and conditions.

This request was willingly granted. Indeed, the poor insect himself, I imagine, was glad enough to rest a while. From somewhere in his packages John Dolittle produced an emergency ration of chocolate which he had been saving up. All four of us munched in silence, too hungry and too awed by our new surroundings to say a word.

The light changed unceasingly. It reminded me of the Northern Lights, the Aurora Borealis. You would gaze at the mountains above you, then turn away a moment, and on looking back find everything that had been pink was now green, the shadows that had been violet were rose.

Breathing was still kind of difficult. We were compelled for the moment to keep the "moon-bells" handy. These were the great orange-coloured flowers that the moth had brought down for us. It was their perfume (or gas) that had enabled us to cross the airless belt that lay between the Moon and the Earth. A fit of coughing was always liable to come on if one left them too long. But already we felt that we could in time get used to this new air and soon do without the bells altogether.

The gravity too was very confusing. It required hardly any effort to rise from a sitting position to a standing one. Walking was no effort at all—for the muscles—but for the lungs it was another question. The most extraordinary sensation was jumping. The least little spring from the ankles sent you flying into the air in the most fantastic fashion. If it had not been for this problem of breathing properly (which the Doctor seemed to feel we should approach with great caution on account of its possible effect on the heart) we would all have given ourselves up to this most light-hearted feeling which took possession of us. I remember, myself, singing songs—the melody was somewhat indistinct on account of a large mouthful of chocolate—and I was most anxious to get down off the moth's back and go bounding away across the hills and valleys to explore this new world.

But I realize now that John Dolittle was very wise in making us wait. He issued orders (in the low whispers which we found necessary in this new clear air) to each and all of us that for the present the flowers were not to be left behind for a single moment.

They were cumbersome things to carry but we obeyed orders. No ladder was needed now to descend by. The gentlest jump sent one flying off the insect's back to the ground where you landed from a twenty-five-foot drop with ease and comfort. Zip! The spring was made. And we were wading in the sands of a new world.

2. THE LAND OF COLOURS AND PERFUMES

We were after all, when you come to think of it, a very odd party, this, which made the first landing on a new world. But in a great many ways it was a peculiarly good combination. First of all, Polynesia: she was the kind of bird which one always supposed would exist under any conditions, drought, floods, fire or frost. I've no doubt that at that time in my boyish way I exaggerated Polynesia's adaptability and endurance. But even to this day I can never quite imagine any circumstances in which that remarkable bird would perish. If she could get a pinch of seed (of almost any kind) and a sip of water two or three times a week she would not only carry on quite cheerfully but would scarcely even remark upon the strange nature or scantiness of the rations. Then Chee-Chee: he was not so easily provided for in the matter of food. But he always seemed to be able to provide for himself anything that was lacking. I have never known a better forager than Chee-Chee. When every one was hungry he could go off into an entirely new forest and just by smelling the wild fruits and nuts he could tell if they were safe to eat. How he did this even John Dolittle could never find out. Indeed Chee-Chee himself didn't know.

Then myself: I had no scientific qualifications but I had learned how to be a good secretary on natural history expeditions and I knew a good deal about the Doctor's ways.

Finally there was the Doctor. No naturalist has ever gone afield to grasp at the secrets of a new land with the qualities John Dolittle possessed. He never claimed to know anything, beforehand, for certain. He came to new problems with a childlike innocence which made it easy for himself to learn and the others to teach.

Yes, it was a strange party we made up. Most scientists would have laughed at us no doubt. Yet we had many things to recommend us that no expedition ever carried before.

As usual the Doctor wasted no time in preliminaries. Most other explorers would have begun by planting a flag and singing national anthems. Not so with John Dolittle. As soon as he was sure that we were all ready he gave the order to march. And without a word Chee-Chee and I (with Polynesia who perched herself on my shoulder) fell in behind him and started off.

I have never known a time when it was harder to shake loose the feeling of living in a dream as those first few hours we spent on the Moon. The knowledge that we were treading a new world never before visited by Man, added to this extraordinary feeling caused by the gravity, of lightness, of walking on air, made you want every minute to have some one tell you that you were actually awake and in your right senses. For this reason I kept constantly speaking to the Doctor or Chee-Chee or Polynesia—even when I had nothing particular to say. But the uncanny booming of my own voice every time I opened my lips and spoke above the faintest whisper merely added to the dream-like effect of the whole experience.

However, little by little, we grew accustomed to it. And certainly there was no lack of new sights and impressions to occupy our minds. Those strange and ever changing colours in the landscape were most bewildering, throwing out your course and sense of direction entirely. The Doctor had brought a small pocket compass with him. But on consulting it, we saw that it was even more confused than we were. The needle did nothing but whirl around in the craziest fashion and no amount of steadying would persuade it to stay still.

Giving that up, the Doctor determined to rely on his moon maps and his own eyesight and bump of locality. He was heading towards where he had seen that tree—which was at the end of one of the ranges. But all the ranges in this section seemed very much alike. The maps did not help us in this respect in the least. To our rear we could see certain peaks which we thought we could identify on the charts. But ahead nothing fitted in at all. This made us feel surer than ever that we were moving toward the Moon's other side which earthly eyes had never seen.

"It is likely enough, Stubbins," said the Doctor as we strode lightly forward over loose sand which would ordinarily have been very heavy going, "that it is only on the other side that water exists. Which may partly be the reason why astronomers never believed there was any here at all."

For my part I was so on the look-out for extraordinary sights that it did not occur to me, till the Doctor spoke of it, that the temperature was extremely mild and agreeable. One of the things that John Dolittle had feared was that we should find a heat that was unbearable or a cold that was worse than Arctic. But except for the difficulty of the strange new quality of the air, no human could have asked for a nicer climate. A gentle steady wind was blowing and the temperature seemed to remain almost constantly the same.

We looked about everywhere for tracks. As yet we knew very little of what animal life to expect. But the loose sand told nothing, not even to Chee-Chee, who was a pretty experienced hand at picking up tracks of the most unusual kind.

Of odours and scents there were plenty—most of them very delightful flower perfumes which the wind brought to us from the other side of the mountain ranges ahead. Occasionally a very disagreeable one would come, mixed up with the pleasant scents. But none of them, except that of the moon bells the moth had brought with us, could we recognize.

On and on we went for miles, crossing ridge after ridge and still no glimpse did we get of the Doctor's tree. Of course crossing the ranges was not nearly as hard travelling as it would have been on Earth. Jumping and bounding both upward and downward was extraordinarily easy. Still, we had brought a good deal of baggage with us and all of us were pretty heavy-laden; and after two and a half hours of travel we began to feel a little discouraged. Polynesia then volunteered to fly ahead and reconnoitre, but this the Doctor was loath to have her do. For some reason he wanted us all to stick together for the present.

However, after another half-hour of going he consented to let her fly straight up so long as she remained in sight, to see if she could spy out the tree's position from a greater height.

3. THIRST!

So we rested on our bundles a spell while Polynesia gave an imitation of a soaring vulture and straight above our heads climbed and climbed. At about a thousand feet she paused and circled. Then slowly came down again. The Doctor, watching her, grew impatient at her speed. I could not quite make out why he was so unwilling to have her away from his side, but I asked no questions.

Yes, she had seen the tree, she told us, but it still seemed a long way off. The Doctor wanted to know why she had taken so long in coming down and she said she had been making sure of her bearings so that she would be able to act as guide. Indeed, with the usual accuracy of birds, she had a very clear idea of the direction we should take. And we set off again, feeling more at ease and confident.

The truth of it was of course that seen from a great height, as the tree had first appeared to us, the distance had seemed much less than it actually was. Two more things helped to mislead us. One, that the moon air, as we now discovered, made everything look nearer than it actually was in spite of the soft dim light. And the other was that we had supposed the tree to be one of ordinary earthly size and had made an unconscious guess at its distance in keeping with a fair-sized oak or elm. Whereas when we did actually reach it we found it to be unimaginably huge.

I shall never forget that tree. It was our first experience of moon life, in the Moon. Darkness was coming on when we finally halted beneath it. When I say darkness I mean that strange kind of twilight which was the nearest thing to night which we ever saw in the Moon. The tree's height, I should say, would be at least three hundred feet and the width of it across the trunk a good forty or fifty. Its appearance in general was most uncanny. The whole design of it was different from any tree I have ever seen. Yet there was no mistaking it for anything else. It seemed—how shall I describe it?—alive. Poor Chee-Chee was so scared of it his hair just stood up on the nape of his neck and it was a long time before the Doctor and I persuaded him to help us pitch camp beneath its boughs.

Indeed we were a very subdued party that prepared to spend its first night on the Moon. No one knew just what it was that oppressed us but we were all conscious of a definite feeling of disturbance. The wind still blew—in that gentle, steady way that the moon winds always blew. The light was clear enough to see outlines by, although most of the night the Earth was invisible, and there was no reflection whatever.

I remember how the Doctor, while we were unpacking and laying out the rest of our chocolate ration for supper, kept glancing uneasily up at those strange limbs of the tree overhead.

Of course it was the wind that was moving them—no doubt of that at all. Yet the wind was so deadly regular and even. And the movement of the boughs wasn't regular at all. That was the weird part of it. It almost seemed as though the tree were doing some moving on its own, like an animal chained by its feet in the ground. And still you could never be sure—because, after all, the wind was blowing all the time.

And besides, it moaned. Well, we knew trees moaned in the wind at home. But this one did it differently—it didn't seem in keeping with that regular even wind which we felt upon our faces.

I could see that even the worldly-wise practical Polynesia was perplexed and upset. And it took a great deal to disturb her. Yet a bird's senses towards trees and winds are much keener than a man's. I kept hoping she would venture into the branches of the tree; but she didn't. And as for Chee-Chee, also a natural denizen of the forest, no power on earth, I felt sure, would persuade him to investigate the mysteries of this strange specimen of a Vegetable Kingdom we were as yet only distantly acquainted with.

After supper was despatched, the Doctor kept me busy for some hours taking down notes. There was much to be recorded of this first day in a new world. The temperature; the direction and force of the wind; the time of our arrival—as near as it could be guessed; the air pressure (he had brought along a small barometer among his instruments) and many other things which, while they were dry stuff for the ordinary mortal, were highly important for the scientist.