6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

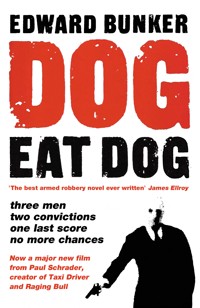

THREE MEN - TWO CONVICTIONS - ONE LAST SCORE - NO MORE CHANCES Carved from a lifetime of experience that runs the gamut from incarceration to liberation. Dog Eat Dog is the story of three men fresh out of prison who now have the task of adapting to civilian life. The California three strikes law looms over them, but what the hell, they're going to do it their way. Troy, an aloof mastermind, seeks an uncomplicated, clean life but cannot get away from his hatred for the system. Diesel is on the mob's payroll and interest in his suburban home and nagging wife is waning. The loose cannon of the trio, Mad Dog, is possessed by true demons within, that lead him from one explosive situation to the next. One last big hit, one more jackpot, and they'll be set for life. Troy constructs the perfect crime and they pull it off, but it is still not enough to prevent a denouement that has a grim and violent inevitability about it.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Dog Eat Dog is the tale of three unremorseful criminals with two felony convictions apiece and no more chances. Under California’s ‘Three Strikes’ law, one more conviction – even for shoplifting – carries a mandatory life sentence with no prospect of remission. But a law intended to deter career criminals has the opposite effect on these three. Combined they have spent a lifetime behind bars and have no idea, or intention, of leading a straight life under rules set by a system they have never belonged to.

Troy, the gang’s leader and the brains of the operation, is an unrepentant thief who is ‘irrevocably committed to being the criminal outsider. He had nothing vested in society. It had turned him out and expected him to be satisfied as a menial worker as the price for staying out of prison. Real freedom has choices attached; without money there is none’. And with that in mind, Troy and his partners, Diesel Carson and the truly rabid Mad Dog McCain, set about planning a last big heist which will set them up for life. But even a perfectly planned and flawlessly executed robbery is not enough to prevent a denouement which has a grim inevitability about it.

Edward Bunker, Mr Blue in Reservoir Dogs, was the author of No Beast So Fierce, Little Boy Blue, Dog Eat Dog, The Animal Factory and his autobiography, Mr Blue, all published by No Exit. He was co-screenwriter of the Oscar nominated movie, The Runaway Train, and appeared in over 30 feature films, including Straight Time with Dustin Hoffman, the film of his book No Beast So Fierce. Edward Bunker died in 2005 and another novel, Stark, was discovered in his papers. Along with some short stories published as Death Row Breakout.

‘Integrity, craftsmanship and moral passion…an artist with a unique and compelling voice’–William Styron

‘Edward Bunker is a true original of American letters. His books are criminal classics: novels about criminals, written by an ex-criminal, from the unregenerately criminal viewpoint.’–James Ellroy

‘At 40 Eddie Bunker was a hardened criminal with a substantial prison record. Twenty-five years later, he was hailed by his peers as America’s greatest living crimewriter’–The Independent

www.noexit.co.uk

To Bill Styron, Blair Clark, and Paul Allen friends and advisors

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Prologue 1981

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Copyright

Introduction

by William Styron

Is it true that for a writer there should be no area of experience that is off limits to his imagination? As a novelist who has ventured far afield into alien territory, I have always felt that it is a writer’s prerogative to deal with places and events of which he does not necessarily have firsthand knowledge. The imagination is sovereign and its power, almost alone, according to my theory, should be able to transform any subject into something wondrous, if the writer is good enough, so that his world will appear more real to the reader than the world of a writer who may have total familiarity with his milieu but possesses a lesser talent. Certainly there are examples of these triumphant forays into terra incognita. Stephen Crane had no acquaintance whatever with warfare, yet his portrayal of the horrors of combat in The Red Badge of Courage remains one of the great fictional accounts of the Civil War or, indeed, any war. Its author never set foot in Africa, yet Henderson the Rain King, Saul Bellow’s novel of the Dark Continent, shimmers with authenticity.

Is there any region of experience, then, where the intrusion of a writer unfamiliar with its realities should be discouraged? Once again I was about to say no, but in fact I believe there is such a place, and that is the modern American underworld, the landscape inhabited by the hardened criminal. This is a province of our society so remote from the happenings of the middle-class book reader, a place so corrupt and violent, populated by human beings so grotesquely and unpredictably different from you and me, that its appalling contours and the behavior of its denizens can be portrayed only by a writer who has been there. Edward Bunker has been there. A little over twenty years ago, Bunker, who was then approaching forty, was set free from prison after serving nearly continuous confinement in state and federal institutions since the age of eleven. During the years after his release, in his role as witness to the Los Angeles underworld, Bunker has produced a series of tough, gritty, painstakingly crafted narratives that has revealed better than any contemporary novelist the anatomy of the criminal mind.

Like so many criminals Bunker was the product of a dysfunctional, alcoholic family. Growing up in Los Angeles as an adolescent in the years following World War II, he fell into a pattern of petty crime that led to his being sent to a reformatory. After his release at the age of sixteen he resumed a criminal career that was considerably more hazardous, involving as it did professional shoplifting and drug dealing. An arrest on drug charges earned him a year in the Los Angeles county jail, from which he promptly escaped. He was caught and given two concurrent sentences of six months to ten years in San Quentin. He was of course still only a teenager. It was while he was in San Quentin, where he served four and a half years, that Bunker diverged in his behavior from that of most young convicts and acquired a passion that eventually saved his life—although his salvation would come only after many more years behind walls. He discovered books. He became a consecrated reader, ransacking the prison library in his newfound hunger for the printed word; his enthusiasm turned him into an aspiring writer who scribbled indefatigably away in his cell, with immense pleasure though with no success in publication.

When Bunker was released on parole from San Quentin, at the age of twenty-three, he entered a phase in his life whose grimly frustrating nature would provide a key to his later work. In No Beast So Fierce, Bunker’s powerful first novel published many years later, the theme is that of a young ex-convict—attractive, promising, eager to make his way in society—whose prison record is enough by its very existence to cause doors to be shut unremittingly in his face. Like his fictional protagonist, Bunker tried desperately to adapt himself to the new straight world, making countless efforts to get legitimate jobs, but the shadow of San Quentin was too baleful and persistent: Society had locked him out. He turned to crime once more (masterminding robberies, extorting pimps and madams in a protection scheme, forging checks), was caught, convicted, and sent to San Quentin again with a sentence bearing a fourteen-year ceiling. This was Bunker’s longest continuous sentence and he served half of it. They were seven agonizing years. He has described this period as one of near madness (a profoundly rebellious streak caused him more than once to suffer the terrors of The Hole—solitary confinement), but his furious love affair with the written word, which kept him reading and writing, provided a kind of spiritual rescue and also, in concrete terms, four unpublished novels and dozens of short stories. He emerged again from behind bars, with a hunger to succeed as a writer of fiction.

But it should be no surprise, given the fate of so many ex-convicts in America, that Bunker’s new freedom was short-lived. Once more his prison record was a curse. After writing over two hundred applications for legitimate jobs and receiving not a single answer, after walking the streets until his feet blistered, after responding to ads week after week only to be turned away, Bunker headed out again on the crime route. He burglarized a safe in a bar and was captured after a high-speed automobile chase. He made bail while awaiting trial but was then seized by what would appear to be euphoric overconfidence: He decided to rob what he has described as a “prosperous little Beverly Hills bank.” Unaware that his car had been wired with a beeper by narcotics agents, who thought he was on his way to a drug deal, the heavily armed Bunker was trailed to the bank, where he was caught at gunpoint and badly beaten. He was tried on federal charges, sentenced to six years, and transported to the McNeil Island penitentiary on Puget Sound in Washington.

At McNeil Island, Bunker’s insurgent spirit once again got him into trouble. Enraged at being housed in a ten-man cell, he went on strike and for his defiance was sent to the nation’s most fearsome lockup, the maximum-security prison at Marion, Illinois. There, despite monstrous handicaps and restrictions, he displayed his invincible scorn for the system by continuing to write fiction. And it is the writing, of course—the dedicated, passionate writing—that eventually saved Edward Bunker.

No Beast So Fierce was accepted for publication while Bunker was awaiting trial for the Beverly Hills bank robbery, and was published in 1973, during his incarceration at Marion. The book received generally fine reviews and gained its author widespread attention, adding to the luster he had already gradually acquired as a brilliantly outspoken literary convict who had written eloquent essays about prison life and prison conditions in such journals as Harper’s and The Nation. By the time his second novel, The Animal Factory, was completed in his cell at Marion, Bunker’s reputation in the vast national prison cosmos shone so brightly that it plainly contributed to his final parole.

This last release was in 1975. Since then he has lived the life of a peaceable citizen, settling in his native Los Angeles where he has married, fathered a son, and has continued to write fiction (his third novel, Little Boy Blue, appeared in 1982), while also pursuing a successful career as a screenwriter. In 1978, a remarkably powerful (though mysteriously neglected) film version of No Beast So Fierce, with a script by Bunker, was produced under the title Straight Time, starring Dustin Hoffman in a taut, superbly focused performance as a prototypal Eddie Bunker. The character is a desperate ex-convict whose decent aspirations are thwarted by a society bent upon denying such men their right to rehabilitation and redemption.

In Bunker’s novels the failure to achieve redemption is joined by another motif: the wretched abandonment of our children. This theme, obviously derived from Bunker’s own bitter and brutalizing experience, reoccurs throughout all his fiction, and in Dog Eat Dog, his fourth novel, the outcast protagonist is Troy Cameron. Like Bunker, he is a reformatory graduate, and as one follows his progress through this raw, unrelenting, sometimes terrifyingly brutal narrative, tracking his lawless spree in the company of two other reform school alumni, Diesel Carson and Mad Dog McCain, one perceives that the subtext in the work, as in all of Bunker’s writing, is that of the perpetuation of violence and cruelty. For Bunker, crime is nurtured in institutional cradles and those who are abused and spiritually mutilated in their earliest youth, whether within the family or in the foster home or the reformatory, grow up to become society’s bloody marauders. Dog Eat Dog is a novel of excruciating authenticity, with great moral and social resonance, and it could only have been written by Edward Bunker, who has been there.

Prologue 1981

“Hup, two, three, four! Hup, two, three, four. Column right … march!” The monitor called the cadence and bellowed the command. The thirty boys of Roosevelt cottage marched in step through the summer twilight. Each affected a demeanor of extreme toughness. Even those who were really afraid managed to hold up the meanest mask they could. Faces were stone, eyes were icy, mouths that seldom smiled would sneer easily. In the underclass fashion of the moment, they pulled their pants absurdly high, virtually to their chests, and cinched their belts tight. Although they kept in step, each had a stylized swagger. They marched like a military academy, but were inmates of a California reform school. Aged from fourteen to sixteen, they were among the toughest of their age. Nobody got to reform school for truancy or writing on walls. It took several arrests for car theft or burglary. If it was a first offense, it was armed robbery or a drive-by shooting.

Situated thirty miles east of downtown Los Angeles, the state school was located on the earliest tract maps of the area, when L.A. had a population of 60,000 and farmland was cheap. Once, the reform school had resembled a small college. Sweeping lawns and sycamores framed buildings that resembled manor houses with brick walls and sloping slate roofs. A few of the old buildings still remained, empty relics from the age when society believed the young could be salvaged—back before the days when kids packed MAC—back when Bogart and Cagney were tough-guy role models. They only killed “dirty rats,” invariably with a snub-nose, up close, not “spray and pray.”

The marching boys halted while The Man unlocked the gate to the recreation yard. As they marched inside, he counted them. The yard was formed by a chain-link fence topped with rolled barbed wire. The Man nodded to the monitor. “Dismissed” yelled the monitor.

The neat ranks disintegrated and formed clusters by race. Chicanos were half the total, fifteen, followed by nine blacks, five whites, and a pair of half-brothers, one of whom was Vietnamese while his half-brother was a quarter Native American, a quarter black and half Vietnamese. The half brothers glared at the whole world with baleful challenge.

The Chicanos and two of their white homeboys from East L.A. headed for the handball court, a free-standing wall that allowed a game on each side. The blacks picked sides for half-court basketball.

The three remaining whites came together and began to pace the length of the yard next to the fence topped with barbed wire. One of them wore new black oxfords, identical to U.S. Navy issue. The shoes were issued to be broken in a week before parole. It was Saturday and Troy Cameron was being released on Monday morning.

“How many you got left?” Big Charley Carson asked. At fifteen, he was six foot two and weighed under 150 pounds. He would gain eighty before he turned twenty-one. By then he would be powerful enough to be nicknamed “Diesel.”

“One day and a getup,” Troy said. “Forty hours. Short as a mosquito’s dick.”

The third member of the trio grinned, simultaneously raising a hand to his mouth to hide his discolored teeth. He was Gerald McCain, already nicknamed “Mad Dog” for insane behavior, the most notorious being the use of an aluminum baseball bat on a sleeping bully who had pushed McCain around. In the Hobbesian world of reform school, a maniac is given wide berth. Tough and mean is one thing; crazy is something strange, different and frightening.

The trio kept walking as the shadows lengthened. The background to their conversation was the crash of weights descending on the platform, the basketball dribbled on asphalt and rattling the metal backboard and hoop, aided by exclamations of delight or curses of frustration. A few more steps and it was the special sound of a little black handball whacking into the wall. The tally was always called in la lengua de Aztlan, a street patois basically Spanish liberally laced with English. Handball was the game of the barrio, for it took but a wall and a ball. “Point! Cinco servin’ three. Dos juegos a nada.”

The game over, the two losers left the court with each accusing the other of causing the loss. The Chicano who was keeping tally had the next game. He looked around for a partner and spotted Troy. “Hey, Troy … homeboy! Venga. Let’s whip these farmers.”

Troy looked at the competition, Chepe Reyes and Al Salas. Chepe was beckoning in a challenge.

“I’m wearing these shoes.” He indicated the black dressouts, which would be scuffed badly on a concrete handball court.

“Go ahead,” said Big Charley. “Use mine.” He took off his low-cut athletic shoes.

Troy changed shoes, took off his shirt, and wrapped a bandanna around his palm. A handball glove was better, but in lieu of that, a bandanna would serve. He was ready. He bounced the ball off the wall a few times to loosen up. At fifteen a long warm-up was unnecessary. “Let’s go. Throw for serve.” He tossed the ball to his partner.

The game began, Troy playing front. They played hard, diving on the concrete for low balls. At one point, halfway through the game, Troy’s partner ran forward to get a ball. Troy anticipated the opponent’s shot—high and to the rear—and Troy was running before it was hit.

Looking back for the ball, he failed to see the three black youths with their backs turned until the last fraction of a second. He managed to half raise his hands before the crash sent two stumbling and knocked the other down.

“Oh, man … sorry about that,” Troy said, extending a hand. He knew the black youth: Robert Lee Lincoln, called R. Lee. At fifteen he had the body of a twenty-two-year-old bodybuilder, an IQ of eighty-five and the emotional control of a two-year-old, plus he hated rich white people. Troy knew some of this; he had avoided R. Lee during the two months since the black arrived.

He wasn’t surprised when R. Lee’s response to apology was to put both hands on Troy’s chest and shove. “Muthafucker … watch it. I don’ be likin’ you muthafuckers no way.” The words dripped contempt and challenge. R. Lee’s chin jutted, so he was peering down his nose with glittering eyes of racial hate. Inside Troy was the thought, This fuckin’ nigger! The word was one that Troy used only in specific situations. It was applicable only to blacks who acted like niggers—loud, crude, stupid—just like redneck fit certain ignorant whites. But mixed with the first thought were two others. In a fistfight he would take an ass-kicking. He was tempted to sneak a punch right now without warning, while R. Lee was still posing. If the Sunday punch landed clean, he might be able to swarm and win before R. Lee got going. But if Troy did that, he would lose his parole. He could see The Man coming toward them. “Knock it off there,” The Man said.

R. Lee turned away with the parting words: “We’ll finish this shit later.”

Troy turned back toward his waiting friends. A hollow sensation was spreading in waves from his gullet to the rest of his body. Fear was sucking his will away. He could never whip R. Lee in a fight; the nigger was too big, too strong, too fast, and could really fight. That was the smallest fear; Troy had planned ahead for such matters. He would unscrew a firehose nozzle and strike without warning. It would never be a fistfight. He would win a Pyrrhic victory, for his parole would go down the drain as soon as he struck.

“Damn,” he muttered.

“That nigger’s crazy,” Big Charley said. “He’s one of them hate whitey motherfuckers.”

“Yeah.” He managed a snorting half-laugh. “Right now I hate niggers.”

What the fuck should he do? Maybe they wouldn’t take his parole if it was just a fistfight, but that would mean getting an ass-kicking. Maybe he could get in a couple of punches. “I half-ass wish I didn’t have this parole,” he said.

“Oh yeah,” Mad Dog said. “I forgot about your parole. That’s a bitch.”

Troy could go to The Man and seek protection for the last two days. They could lock him up for two days. He would lose nothing—except his good name in his world. He reviled himself for even letting it go through his mind. Anything like that was totally out of the question. If he did something like that, he would be marked in the underworld, where he intended to live, for his whole life. It would be a stigma he could never erase. It would forever invite aggression.

“Lemme take care of it,” Mad Dog offered. “I’ll steal him.”

Troy shook his head. “No. I’ll handle my own shit.”

The blast of the police whistle, the signal to line up at the door into the building, cut the twilight.

As the youths filed inside, The Man stood in the doorway and counted them. Indoors, some hurried down the hall toward the TV room; they wanted the best seats. Those who had been playing handball or basketball or lifting weights made a left turn into the washroom. There were three communal washbasins, each with three faucets.

Troy watched R. Lee in line ahead of him. R. Lee turned left. Good. It would give Troy a chance to turn right into the dormitory. The firehose was just inside the door. The brass nozzle would bust a head like an eggshell if he swung it that hard. He had decided it was all he could do. He hated R. Lee more for his ignorance, for forcing this, for taking away imminent freedom.

R. Lee was no fool. He knew Troy was behind him. As R. Lee turned into the washroom, he watched the doorway behind him via the mirror. He stripped off his T-shirt and stepped up to the sink. Because he was watching the door, he missed Mad Dog in the stall toilet to the right.

Mad Dog flushed the toilet with his foot and turned. Down beside his leg was a toothbrush handle. It had been melted and, while soft, two pieces of razor blade had been fitted in. When it hardened the blades stuck out less than a quarter of an inch—small but very sharp. He came behind the youths at the washbasins. It took just two seconds to reach R. Lee.

Mad Dog put the blade on the brown back and sliced all the way from shoulder to waist. The flesh lay open like lips for a moment; then the blood welled up and poured forth.

R. Lee screamed and whirled, simultaneously reaching back at the wound and looking for the attacker. Mad Dog was wide-eyed, a hyena looking for an opening to dart in and slash again.

Another black had seen the blow from across the room. He yelled, “Watch it!” and came pushing through.

Mad Dog cocked his arm back, a scorpion flashing its tail. The second black stopped out of range. “You fucked up, honky!”

“Fuck you, nigger!”

The Man saw the chaos and hit the panic alarm he carried.

In the dormitory door, Troy heard the yells and saw boys rushing toward the washroom. As he stepped into the hallway, R. Lee burst through the crowd in the opposite doorway and ran for the outer door. His whole back was covered with blood flowing profusely onto the back of his pants and the floor. He began kicking on the front door. “Lemme out! Lemme out! Lemme go to the hospital.”

Troy saw a couple of blacks looking at him. He had the firehose nozzle wrapped in newspaper. If they made a move, he would bash a head.

The Man pushed through to the outer door. He unlocked it and R. Lee ran out.

Coming the other way were the freemen, carrying night-sticks, their keys jangling on their hips.

The cottage was put on lockdown, with extra personnel watching.

R. Lee needed two hundred and eleven stitches.

Mad Dog went to the hole.

On Monday morning. Troy was released on parole. He owed his release to Mad Dog. It was a debt he carried into the future.

1

Two nights alone in a room with a pair of one-ounce jars of pharmaceutical cocaine made Mad Dog McCain live up to his nickname. The cocaine was better than what was peddled on the street. It came from a doctor’s bag he’d stolen from a car in a medical building parking lot. He’d originally planned to sell it after using a little bit, but when he approached the few people he knew in Portland, they either wanted credit or ridiculed cocaine as “powdered paranoia” or “twenty minutes to madness.” They all wanted heroin, a drug that made them calm instead of insane.

A little bit made him feel great, so he used a little more, and the fangs of the serpent were in him. First he chopped the flakes with a razor blade, formed lines, and tooted them up the nose, and that was good. But he knew how to get a bigger bang. The doctor’s bag had a package of disposable syringes with attached needles. All the pure cocaine took was a few drops of water and it dissolved. Drop in a matchhead-size piece of cotton to draw it through, and then tap the needle into the hard ridge of vein at the inner aspect of the elbow. It was hard to miss. Now his arm was black and blue and had scabs from earlier injections. His tank top was filthy and showed where he’d used the bottom to wipe away the blood from his arm. That didn’t matter. Nothing mattered, except the flash. When the needle penetrated the vein, red blood jumped into the syringe. He squeezed a little; then let the blood back up into the syringe.

When the glow started to course through him, he squeezed off a little more. What a flash! If he … could … just … maintain … the flash … Oh God! Ohhh … So good … so fucking good as it went through his body and his brain.

Stop. Let it back up into the syringe again. Squeeze off more.

Repeat, until the syringe was empty.

He closed his eyes, moaning softly as he savored the ecstasy. He was king of everything now.

From the nightstand ashtray, he took a cigarette butt. While he straightened it out to light, he saw Troy’s letter from San Quentin on top of a pile of unopened mail. Good news. Troy had a parole date three months away. As soon as Troy raised, they would get rich together. Troy was the smartest criminal Mad Dog knew, and he’d known thousands. Troy knew how to plan things. What a great idea, heisting dope dealers and wannabe gangsters, assholes who couldn’t yell copper. It would be great to have big money. He would buy Sheila the clothes she was always looking at in women’s magazines and catalogs. He might even get her a Mustang convertible. She had it coming. She was a good broad. Halfass pretty, too, if she’d lose fifteen or twenty pounds. Then again he wasn’t exactly Tom Cruise either. The thought made him laugh in the shallow way that cocaine allows. He had gaps in his dental work, a hole where a partial plate provided in prison had once been, until a Budweiser bottle in an Okie bar in Sacramento had wiped it out. Of course the evening hadn’t ended there. When the Tulsa Club closed, he was waiting in the parking lot, a scuba diver’s knife up his sleeve. When the bottle swinger unlocked his car, Mad Dog came out of the shadows bare-handed, as if it were a fistfight. When he was in close, his head on the guy’s chest, Mad Dog let the knife slide down into his hand. He sank it into the guy’s guts two or three times before the guy realized it and ran, trying to hold his entrails inside his body.

Remembering, Mad Dog grinned. That would teach a motherfucker who to fuck with—if he lived. It was the reason Mad Dog had moved to Portland, where he had met Sheila.

He looked around the room. It was on the second floor and overlooked the flight of stairs to the street. Things were a dope fiend mess. Newspapers, socks, clothes, and bedding were strewn around. He’d torn the bedding off when a cigarette had fallen from his hand and the mattress had started to smolder. He’d been watching the Trailblazers tear up the Lakers when he’d smelled smoke. Water from the goldfish bowl had failed to stop it. He’d had to tear the mattress open and dig out the smoldering cotton. The hole was now covered with a towel, but the odor still filled the room. What would Sheila say when she got home?

Who gives a fuck, he thought. Fuck her … fat bitch. Where was she? She was supposed to come back tonight with her chubby little daughter.

Mad Dog felt his armpit. Wet and slippery and smelling bad. The drug coming through his pores had a sour stench. He needed a shower. Shit, he needed a lot of things. But right now, he needed another shot of coke.

Thirty minutes and two fixes later, he had the light out and was peeking past the corner of the windowshade at the rainy night. When he’d started this cocaine binge, a fix would lift him to the heights for half an hour or more, and then let him down slow and easy. Now the cycle was quicker. Joy barely lasted until the needle was out. Within minutes the craving began and with it the seeds of dread and paranoia and self-loathing. The only remedy was another fix.

He peered down at the street from the old frame house that was built into a hillside near a railroad bridge. Because of the slope and the retaining wall, he couldn’t see the sidewalk on his side of the street except where the stairs came up.

A car went by; then nothing but dark rain, the drops flashing momentarily in the glow of a street lamp. The craving for cocaine turned into a scream behind his eyes. He had delayed as long as possible, trying to make it last longer. It was nearly gone. Two ounces of pharmaceutical cocaine in forty hours. That was drug use of legendary scale. With heroin he would have folded into a drugged stupor long ago. Heroin had a limit, but cocaine was different: You always wanted more.

He found a vein and watched the blood rise. Instead of the usual practice of squeezing a little and stopping, and then doing a little more, he forgot and squeezed it all in.

It went through him like electricity. Instantly everything in his stomach flew from his mouth. Oh God! His heart! His heart! Had he killed himself? He spun and walked, careening off a chair, banging into a wall, then into the dresser. Oh shit! Oh God! Oh! Oh! Oh!

The flash dissipated, and with it his terror. He closed his eyes and savored the sensation. No more like that one, he swore.

Headlight beams flashed across the windowshade. Mad Dog went to the window. A car had made a U-turn and pulled up at the curb. The retaining wall blocked his view except for the bumper and headlights. Who the fuck could it be at this time of night?

He turned off the light and watched.

The car below pulled away. A taxi. Sheila and Melissa, her seven-year-old daughter named for a song, came into view at the bottom of the stairs. He could see Sheila’s white face as she looked up. Mad Dog froze, certain she could see nothing except a black window. She would think he was gone because his car wasn’t at the curb. It was in the service bay of the neighborhood Chevron station awaiting his payment for an alternator, but she didn’t know about that. Good enough. It would give him time to shoot the last of the cocaine before he had to listen to her nagging bullshit. Forgotten was the surge of affection he’d felt earlier. Instead he thought of how she bitched at him about cocaine, and everything else, too.

Mad Dog heard them come in the front door and move around on the bottom floor. He could hear the child’s quick feet, then the back door opening and closing. She was feeding the cat, no doubt. She was a worthless little brat most of the time. She disliked him and refused to do what he said until he promised to beat her butt if she didn’t straighten up. When she complied, it was with a resolutely hangdog manner, pouting and dragging her feet. The only good thing about her was her love of the cat. She was always thoughtful and generous; she’d once used her last dollar for a can of cat food. Mad Dog had a grudging affection for such loyalty.

When he heard the canned laughter on the TV downstairs, he turned on the nightstand lamp; it threw a yellow pool of light on the ritual paraphernalia of the needle. He squirted a small syringe of water directly into the jar; then put on the lid and shook it. That way he would lose nothing. He sucked it through the needle into the syringe. He held it up and squeezed very gently, until a drop appeared at the tip of the point. That meant the air was out of the syringe. He took his time fixing it, savoring it as long as possible. If he could only hold this sensation forever; that would be heaven indeed.

Within minutes the joy was frayed at the edges by inchoate anguish, by self-pity. Why me, God? Why has life been so shitty from the very start? His earliest memory was from age four, when his mother had tried to drown him in the bathtub. His six-year-old sister, who later turned dyke and dope fiend whore, had saved his life by screaming and screaming until the neighbors came. They had stopped his mother and called the police, who had taken the children to juvenile hall, and the judge then sent his mother to Napa State Hospital for observation. Another time, the nurse at school had found the welts on his body where his mother had pinched him, digging in her thumb and forefinger and twisting his flesh. The pain had been awful, and afterward there was a bruise. Remembering it now, three decades later, gave him goose bumps.

She’d gone to Napa twice after that, once for eight months, before she died when he was eleven. He was away from her by then—in reform school. The chaplain called him in to tell him; then looked at his watch and told the boy he could have twenty minutes alone in the office to express his grief. The moment the door closed after the chaplain stepped out, Mad Dog was on his feet reaching for the drawers. He was looking for cigarettes, the most valuable commodity in the reform school economy.

Nothing in the drawers. He went to the closet. Bingo! In a jacket pocket he found a freshly opened pack of Lucky Strikes. L.S.M.F.T. No bullshit! He took them and felt good. He stuffed the pack into his sock and sat back down. That was where he was when the chaplain came back. He wanted to have a talk and he looked at the folder and frowned and said something about “… your father …”

Mad Dog stood up and shook his head. He didn’t want to talk about it. Indeed, he had nothing to say. He knew nothing of his father, not even his name. It wasn’t on his birth certificate. By now his sister, who did have a name on her birth certificate, was calling him “trick baby.” When he looked in the mirror, he was ugly and resembled nobody in the family. Although they were a nondescript bunch, they tended to be tall and pale with stringy hair, whereas he was short and swarthy, with curls so tight they neared being kinky. A loudmouth older boy had once even asked if his mama had a nigger in the woodpile. Ha ha ha. The bully was too big and too mean to challenge, but when the dormitory lights were out and the bully was snoring. Mad Dog crawled along the floor and beat his head soft with a Louisville slugger. The victim survived, but he was never the same; his speech was forever impaired, as was his brain. It was then that Gerry McCain had gotten the nickname “Mad Dog.” It was a nickname he had lived up to in the ensuing years.

The last fix was wearing off; the headache was pulsing behind his eyes. Aspirin. Naw. Aspirin wouldn’t touch this one. Besides, the aspirin was downstairs and he wanted to avoid Sheila’s nagging ass as long as possible. Her shrill voice worked on his brain like fingernails on a blackboard. If he had some dough he would pack up and leave and wait for Troy in California, maybe even Sacramento. Things had cooled off by now. He even had a couple of scores in mind, but he hated doing anything alone and the only possible crime partner around was Diesel Carson. Mad Dog had known Diesel ever since reform school. They’d even taken a score together. That was the reason he wouldn’t do anything with Diesel until Troy resurrected.

His headache was awful, and he could suddenly smell the stink of his own body. Booze and cocaine smelled terrible when you sweat them out. Cocaine was the worst drug. Terrible shit. He hated it. Yet he also craved another fix to postpone the hours of hell fast approaching. What he really needed was a fix of heroin. That was the perfect remedy for the gray scream of depression in his brain. The crash was starting. If he could only sleep through it …

Then he remembered the Valiums. The big ones. Blues. The vial might have eight tablets left. That many would poleax him to sleep. He wouldn’t care about the night sweats and the terrible dreams. He went to the dresser and opened the drawer. Among ballpoint pens, empty butane cigarette lighters, Pepto-Bismol tablets, and other effluvia, he found the little brown vial. He pried off the cap and dumped the contents into his palm. Six! Six! The bitch had been in the bottle.

Anger worsened the headache. He swallowed the six blue tablets with the help of a cold cup of coffee. He threw the empty vial into the wastebasket and started to lie down.

That was when the door opened and the overhead light went on with one hundred watts of brightness. Sheila stood there, her eyes going saucer-wide at the sight of him. She let out a little cry of surprise and her fist went to her mouth.

“What are you doing here?” she asked.

“What the fuck does it look like? Get outta here and leave me alone.” He looked at her and hated her moon face with the blemished skin. How could he have ever thought her pretty? It must have been because he was fresh from prison and a female crocodile would have looked good. “I told you never to come in here without knocking.”

“I didn’t know you were home,” she said. “Your car’s not downstairs and you didn’t come down to say hello. Where is your car?”

“It’s at the gas station getting fixed.”

“Don’t talk to me with that tone of voice. I don’t like it.”

“She doesn’t like it,” he mimicked with scorn. “Ain’t that a bitch.” He leaned forward, looming over her. “I don’t give a rat’s ass what you like or don’t like—bitch!” The pounding blood in his brain made him dizzy. He might have backhanded her except for the child’s voice calling out, “Mommy! Mommy!” The sound of the girl’s footsteps preceded her appearance in the doorway. She went to her mother. When they both faced him they looked alike.

“Let’s go downstairs, honey,” Sheila said, arm around the girl’s shoulder as she turned her and walked her out the door.

“Can I watch Star Trek? It just started.”

“Sure. If you go to bed right afterward. Go on.” She sent the child out and turned back to Mad Dog McCain. She had gotten herself under control. “You’ve got to leave. I don’t want you here anymore.”

“Great. As soon as I get my wheels out of the gas station, I’m gone.”

“Don’t even think about charging it on my card. In fact, gimme the card back.” She extended her hand and snapped her fingers.

“Hey, if you want me to go … I gotta get the car out first.”

“No. Give it here.”

He saw she was unafraid. Why? Because she knew too much about the robbery of the merchant ship’s payroll. She’d worked in the offices of a shipping company, and told him that merchant seaman were still paid in cash at the end of a voyage. She’d told him what ship, when and where. He and Diesel Carson had ripped off eighty-four grand. Sheila knew everything, and even though she was a conspirator, the authorities would certainly drop charges if she testified against Diesel Carson and Mad Dog McCain, a pair of lifelong criminals. Yeah, the bitch thought she had him by the balls. Why the fuck had he trusted her?

He took the Chevron card from his wallet and threw it at her. It fell on the floor. “Bastard,” she said, picking it up and going out, slamming the door as she did so.

He blinked at the door while spinning down, down into the hell of a cocaine crash. Inside him was a silent scream of despair and a growing brute rage. Without the credit card he couldn’t retrieve his car, and without his car he could never make any money. He was stranded. He could become homeless. He had a .357 Python and an AK-47 with a thirty-round clip, enough firepower to heist almost anything—but he couldn’t run around on foot. He needed wheels, and not a carjacking. That was for young niggers who didn’t know how to steal anything worthwhile. Still, he needed wheels more than anyone in their right mind could imagine. It bordered on obsession, and maybe paranoia.

Through the closed door, he heard Sheila and the child enter the next room. Melissa’s bedtime. The thin wall allowed enough sound for him to visualize what was going on. The brat was saying her prayers. Jesusfuckingchrist—he hated religion. He hated God. He loved evil more than good and lying more than speaking the truth. He decided that he was going to get the credit card right now.

When he opened the bedroom door and peered out in the hall, the bedroom door to his right was ajar. They were in there. The stairs were to the left. He was careful to make no noise as he went down. She usually left her purse in the entrance hall next to the front door, but not tonight.

The kitchen. He went that way and, sure enough, it was on the sink. He opened it and removed the billfold. Eight dollars. No Chevron card. He returned the billfold to the purse and looked around. Where had she put it when she came downstairs?

He spotted her cardigan across the back of a chair. She’d been wearing the sweater when she came into his room. He picked the sweater up and felt the pocket. Sure enough, there it was.

He was feeling for the pocket when Sheila came through the door. He pulled out the credit card. “Don’t fuck with me, Sheila. I gotta get my car.”

“Don’t fuck with you. Don’t fuck with me! Gimme that!”

Again she extended her hand and snapped her fingers. The action itself was a slap in the face, and he reacted with rage. He lunged forward. She opened her mouth to scream a moment before his left hand slammed against the side of her head, stunning her.

His right hand darted forward, his fingers closing on her throat.

She kicked him and twisted loose. He open-handed her again, hard enough to knock her against a table, which slid across the floor. A flower vase fell off and crashed on the floor.