9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ryland Peters & Small

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

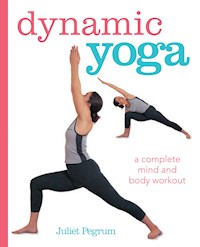

Bring health and harmony to your body, mind and spirit by practising Dynamic Yoga. Dynamic yoga, also known as Ashtanga yoga, a is a more rigorous, powerful form of Hatha yoga. By focusing on balance and controlled breathing as you move quickly through the series of poses in rhythmic routines called Vinyasa, you'll strengthen and rejuvenate yourself in wonderful ways. Juliet Pegrum, an experienced yoga teacher, explains how to achieve each pose so that even beginners can enjoy the benefits right away. Let go of tension in every muscle, and feel relief and a soothing calmness take over. The heat that's generated through practice encourages flexibility, boosts energy, helps the body detoxify and promotes peace of mind. Each fully illustrated sequence prepares your body for what's to come, from warm-ups through sitting, standing and finishing poses. At every stage, you'll know the health benefits that can be attained. Whether you want to encourage restful sleep or prevent lower back pain, you'll feel tranquil and fully refreshed by the experience. Establish a rhythm with weekly schedules specially designed for novices. Every week you'll add more complex poses, advancing at the best pace. Advice on correct breathing, diet and how to relax helps ensure total success. Revitalize yourself with this classic, powerful practice that offers great physical and spiritual benefits.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

dynamic

yoga

dynamic

yoga

a complete mind and body workout

This edition published in 2016 by CICO Books

an imprint of Ryland Peters & Small Ltd

20–21 Jockey’s Fields 341 E 116th St

London WC1R 4BW New York, NY 10029

www.rylandpeters.com

First published in 2001 as Ashtanga Yoga

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Text © Juliet Pegrum 2001

Design and photography © CICO Books 2001, 2016

(Photo on page 16 © Photosindia/Corbis)

The author’s moral rights have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress and the British Library.

eISBN: 978-1-78249-508-6

ISBN: 978-1-78249-346-4

Printed in China

Editor: Mandy Greenfield

Designer: Emily Breen

Photographer: Geoff Dann (page 25 by Richard Jung)

Senior editor: Carmel Edmonds

In-house designer: Fahema Khanam

Art director: Sally Powell

Head of production: Patricia Harrington

Publishing manager: Penny Craig

Publisher: Cindy Richards

important health note

Please be aware that the information contained in this book and the opinions of the author are not a substitute for medical attention from a qualified health professional. If you are suffering from any medical complaint, or are worried about any aspect of your health, ask your doctor’s advice before proceeding. The publisher can take no responsibility for any injury or illness resulting from the advice given, or the postures demonstrated within this volume.

contents

introduction

yoga philosophy

what is dynamic yoga?

elements of dynamic yoga

how to use this book

drinking and eating

how to relax

safety first

chapter one warming up

salute to the sun (a)

salute to the sun (b)

chapter two standing poses

standing sequence

chapter three sitting poses

forward bends

spinal twists and balances

advanced sitting poses

chapter four finishing poses

all limbs cycle

the headstand cycle

chapter five daily practice

schedules

spiritual changes

glossary

index

introduction

Yoga is an enduring, profound philosophy. In this opening section, learn about the ideas and history of yoga, and how they apply to dynamic yoga. Find out how to practice yoga to gain the most benefit from it, including breath control techniques, advice on diet, and key safety tips. You will discover that the practice of yoga is a way of life that brings health and harmony to the body, mind, and spirit.

yoga philosophy

Before beginning to learn yoga, it is helpful to have an overview of the ideas and beliefs surrounding it, as an understanding of these is key to gaining the most from your yoga practice.

The ancient practice of yoga has been traced back to the Puranas, which are Sanskrit chronicles that may date from as early as 6000 BC. Yoga does not belong to any religion; rather, it is an enduring, profound philosophy that embodies some ideas that are common to all religions. The word yoga translates as “the bond,” from its root yuj, meaning “to yoke” or “harness.” This union refers to the highest attainment of the practice, which occurs when the mind becomes fully absorbed in the atman or transcendental soul. This ultimate experience is rarely attained. However, on a day-to-day level, practicing yoga still brings huge benefits to body, mind, and spirit.

Yoga has been passed down from teacher to disciple from ancient times to the present day, and has diversified into many different schools and approaches. The method described in this book is dynamic yoga, also known as Ashtanga yoga (see page 18).

The eight “limbs” of yoga are the subject of the Yoga Sutras (or sayings) written by Patanjali between 400 and 200 BC. Patanjali is known as the architect of yoga because he compiled and systematized the existing knowledge of yoga, giving it a philosophical shape. It is essential to have a basic understanding of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras to bring the mind and sense organs under control, for the achievement of enlightenment.

The aim of yoga is union with the inner self, the essence of all things. Guru Shri Pattabhi Jois (known as Guruji by his students), the founder of dynamic yoga (see page 18), once replied to a question about yoga, “Do your practice and all is coming”—meaning that to grasp something intellectually is not comparable to the experiential knowledge of a subject. Overstimulating the intellect in an effort to understand yoga is counter-productive. The classic example is trying to imagine what sugar tastes like if you have never eaten it. However, as a beginner it is important to have some intellectual understanding in order to propel you farther along the path of yoga.

It is said in the Yoga Sutras, “Let one bring chitta [mind] under control by withdrawing it, wherever it wanders away, drawn by the various objects of sight.” What this means is that only when the mind is completely still, without disturbance, can the true nature of self be experienced.

When the mind is quiet, there is no duality of subject and object—it is free to rest in its own intrinsic qualities, which are joy, equanimity, bliss, and compassion. This may appear to be a simple task, but in my experience, when trying to remain still for just 20 minutes to meditate, the mind conjures up an array of distractions.

Guruji likened the untamed mind to a monkey being led by the five senses, jumping from one thought to the next, completely absorbed in the external world, inquisitive and restless. The wisdom of yoga says that only by turning your attention within will you find true, lasting peace and contentment.

The eight limbs

Patanjali’s eight “limbs” highlight the path by which disturbances (which distract the mind from the experience of yoga) can be removed.

The first four steps consist of the outer practices:

1 restraints (yamas)

2 observances (niyamas)

3 postures (asanas)

4 breath control (pranayama).

The second four steps consist of the inner practices:

5 sense withdrawal (pratyahara)

6 concentration (dharana)

7 meditation (dhyana)

8 self-realization (samadhi), when the eternal self alone shines in the mind.

The last four are collectively referred to as raja yoga, or mind control.

The outer practices

The restraints, or yamas (which translates as “forbearance”), are the first step and consist of five abstentions which relate to your attitude toward others. The restraints establish an ethical code of conduct, and are a means to regain balance in your life. The abstentions include non-harming, truthfulness, non-stealing, non-sensuality, and non-possessiveness. They are referred to as “the great vows” and they continue throughout all levels of yoga practice. There is never a point at which you can say, “Now I am a great yogi and beyond the force of my actions.” The restraints help to regulate the disturbances of body and mind created by desires.

Step one: the restraints

The aim of these restraints is to free oneself from individuality, force, pride, desire, anger, and acquisitiveness, in order to be at one with the infinite spirit.

a Non-harming (ahimsa)

On an extreme level, this translates as “not killing”; on a more subtle level, it incorporates angry thoughts and a willingness to harm any sentient life—and that includes yourself.

b Truthfulness (satya)

If someone is aligned in thought, word, and deed, then the mind is at ease. Any deception, in the hope of winning some sort of advantage over another person or situation, should be avoided.

c Non-stealing (asteya)

This means not taking or using things that belong to others, without their consent.

d Non-sensuality (brahmacharya)

This implies moderation of the senses, including any excess or debauchery in food, sex, or drugs. Managing the senses promotes health, reduces heightened mental activity, and produces more vital energy.

e Non-possessiveness (aparigraha)

This means avoiding the overwhelming desire to have what others possess—whether that be material objects or personal characteristics. Non-possessiveness leads to inner freedom and contentment in life.

By withdrawing from external objects, you begin the process of training your mind, harnessing your energy, and bringing your awareness back to yourself. Other than to sustain bodily functions, external objects will not provide true happiness, peace, and contentment. Yoga is the art of life management, leading to the discovery of joy and purpose within yourself. Many people believe that life would be devoid of pleasure without the support of external stimuli. In reality, objects that appear pleasurable (such as rich food) can lead to all manner of painful physical and emotional problems. Buddhist philosophy likens sensual pleasures to honey on a razor blade—they appear to be sweet, but have painful consequences. In fact, the less you are driven by external objects, the more you are at liberty to appreciate and enjoy them.

Step two: the observances

The observances, or devotions, develop as a direct consequence of the five restraints. They refocus the mind on the inner quest for fulfilment, rather than on dependence upon external circumstances.

a Purity (saucha)

The term purity means both cleansing and the proper nourishment of the body and the mind. External cleanliness includes your living environment as well as your personal bodily cleanliness. Internal cleanliness incorporates both the foods that you eat and mental cleanliness. Negative thoughts or malevolent feelings toward others should always be avoided.

b Contentment (santosha)

This implies complete acceptance of life’s circumstances at any given moment.

c Self-discipline (tapas)

This means putting effort into your spiritual practice, which will lead to self-mastery.

d Self-study (svadhyaya)

This is the study of “the self” (not oneself), by reading the scriptures and the lives of the saints.

e Self-surrender (ishvara pranidhana)

Self-surrender means dedication to the idea of supreme selfhood, which involves the surrender of your whole self to the concept of liberation.

Step three: the postures

Practice of the poses, or asanas, is generally referred to as Hatha yoga, meaning forceful or physical yoga, and forms the third “limb.” The word asana literally translates as “seat,” or steady posture. Through posture practice, the subtle energy channels running throughout the body, known as nadis (see pages 14–15), are purified, conditioning the body to enable it to maintain a steady posture in which to meditate. Yoga philosophy regards the body as the temple of the divine spirit, and therefore it should be cared for and appreciated as a divine gift.

The poses are much more than physical exercises; they are a holistic practice that works on many different levels. They tone the internal organs, regulate the hormones, strengthen the nervous system, build a strong and flexible muscular physique, and produce mental equilibrium. Through the practice of asana, awareness, concentration, and meditation are cultivated—these being the final steps in the development of yoga.

There are said to be 840,000 different poses—supposedly as many poses as there are species of animal living in the universe—and many of them are named after animals and vegetation. Yoga is a celebration of life, realizing the divine spark within all creation.

Asana practice is the aspect of the whole yoga system that has attracted greatest attention in the West. Its purpose, however, is to prepare the body for the ultimate experience of yoga, self-realization (samadhi)—the eighth step.

Step four: breath control

The next “limb” is breath control, or pranayama. Prana translates as “life force,” being a subtle energy that is said to pervade all phenomena and to be present in breath, along with the gross element of air. Ayama means “expansion,” and so the word pranayama signifies the “expansion of the life force.” Breath control has three phases, known as inhalation, retention, and exhalation—and is the gateway to unlocking deeper aspects of the self, since breathing is an unconscious reflex of the body.

The strong connection between breathing and the sympathetic nervous system can be observed by noticing how shallow your breathing becomes when you are afraid or anxious. By deepening your breathing, you calm the mind, increasing the oxygen supply to the body’s physiological system, which is vital for optimum health. There are, however, different varieties of breath-control technique; pranayama is usually taught only after a degree of proficiency in Hatha yoga has been established.

The emphasis is on relaxed breathing. There should be no external restrictions (such as the wearing of tight clothing) and no internal restrictions (such as anxiety, or any undue forcing or holding of the breath). When breathing is free and relaxed, the veil that obscures the goal of enlightenment fades away and the mind becomes ready for fixed attentiveness.

You should not practice breath control without the guidance of an experienced teacher, or you could disrupt the subtle energies of the body. However, if pranayama is practiced properly it has great therapeutic value, especially for breath-related problems such as asthma and coughs, and more generally it invigorates the entire system. Find out more about breath control on page 19.

The inner practices

The next four “limbs” pertain to the states that are experienced in deep meditation. It is important to seek a qualified meditation instructor to guide you through this practice, once your body and mind have reached a steady, balanced level through practice of the first four steps.

Step five: sense withdrawal

Breath control is the path between the outer and inner worlds and begins the transition from the four outer stages of yoga practice to the four inner stages. The fifth “limb” is termed “the retraction of the senses”; it is the withdrawal of the mind from attention to sensuous appearances, which in turn leads directly to the sixth step. The first five steps of the yoga disciplines are collectively known as the method of self-realization (sadhana).

Step six: concentration

The sixth “limb” is known as concentration, or fixed attention, and is an extension of the previous step—holding the mind steady on a single point and not being diverted by seductive sounds, smells, tactile impulses, or distracting thoughts. Thoughts will continuously arise, but by concentrating on a fixed point or object, such as your breathing, you will gain the ability to observe your thoughts without becoming involved in them. After some time, the mind begins to settle, a degree of equanimity starts to develop, and you are no longer disturbed by its various activities. By focusing your attention, you are led naturally to the seventh stage.

Step seven: meditation

The seventh “limb,” meditation, involves the deepening of concentration. It is a further unification of consciousness, at which point discursive thoughts and creative imagination begin to subside. This leads directly to the final stage.

Step eight: self-realization

The “self” referred to in this instance does not mean your ego-related or small self, but rather the essence that is left once all associations and impressions of a distinct inherent self have been removed—simple, pure awareness. Consciousness in its pure state is likened to a flawless diamond, because it is indestructible. Diamonds are by far the hardest substance known to humankind, and, like pure awareness, a perfect diamond is completely transparent and invisible.

The eighth “limb” is also known as ecstasy, whereby the mind becomes as unconscious of itself as it is of any other object. When the life force (prana) is compressed into the spinal column (sushumna nadi) through the practice of yoga, the mind becomes completely absorbed in the soul. Then the body resonates with the divine, which is a state of pure bliss.

There are believed to be different levels of ecstasy, although the ultimate experience of it is very rarely attained.

Energy flow

Yoga philosophy describes an inner or psychic dimension to the body, often referred to as the “subtle body,” which is not visible to the physical eye. A vast network of subtle energy channels, known as nadis (meaning “flow”), crisscross the entire subtle body, and it is through these channels that the energy of prana (life force) flows. When this intricate network is cleansed, energy flows freely throughout the system.

Nadis: energy channels

Yoga texts differ on the exact number of nadis, but there are at least 72,000, of which three are of primary importance. These are the pingala nadi, the ida nadi, and the sushumna nadi, which form the prime conduits of energy throughout the system. One of these three nadis (the pingala) is positive, one (the ida) is negative, and the other (the sushumna) is neutral—just as in any electrical circuit.

Purifying the nadis through yoga poses—Hatha yoga, the third limb—is a way of obtaining enlightenment, the eighth limb and ultimate aim of yoga. The word Hatha comes from ha, meaning “sun,” which represents the positive energy channel. This is situated to the right of the central channel—the neutral nadi—and according to most yogic scriptures, the positive channel terminates in the right nostril. It is associated with the physical faculties of the body and is the masculine energy. Tha, on the other hand, means “moon” and refers to the negative energy channel. This is situated to the left of the central channel. It is generally believed to commence at the base of the spine and extend to the left nostril, coiling around the central channel. It is associated with mental faculties and is the female energy.

The neutral nadi is said to flow from the base of the spine along the spinal column to the crown of the head. When it is activated, both your mental and physical faculties become balanced and the mind is calm. This unification of energy is brought about by the practice of Hatha yoga.

Chakras: energy wheels

Chakras, literally meaning “wheels,” are energy centers situated along the subtle body. Most yoga schools identify seven chakras, located along the central energy channel. It is believed that each of these chakras corresponds to a higher level of consciousness.

The seven chakras are:

1 Root chakra (Muladhara)

This is located at the base of the body, at the perineum (the region between the anus and the genitals). This chakra is stimulated by the action of the root lock (see page 21). This is the location of cosmic energy and the source of the central nadi.

2 Sacral chakra (Svadhishthana)

This chakra is situated in the genital area.