Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Old Pond Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

If you have a passion for heavy machinery, you'll be excited about David Wylie's guide to the Earthmovers of Scotland, complete with over 400 stunning photographs! Wylie has enjoyed privileged access to the mines, quarries, road projects, and forestry of Scotland. He's seen some of the biggest—arguably the best—earthmoving machinery in the world in action. Earthmovers in Scotland brings together 32 of David's reports from these visits to tell the story of the highly skilled, experienced owners, drivers, and managers that work with earthmoving equipment. He explains why they select, maintain, and operate these machines. The book features some of the largest earthmovers in the UK, such as: *Caterpillar's D11R bulldozer *Liebherr's massive 320 tonne R9350s *The mighty 520 tonne Q&K RH200 *And many more! He takes a look at a 1.5 tonne mini digger, special trailers that can lift and transport 1800 tonne bridges, and covers Demag's H485 record-breaking mining shovel amongst others. Taking pride of place in the book are over 400 stunning photographs, many of which have not been seen before and many of which feature machines that were the first of their kind. Each high-quality photo has been carefully composed to capture each machine in all its power and brilliance with the spectacular Scottish scenery as a backdrop, and 80 of the most important and detailed images are presented as double pages to help you get close to the action. This beautiful book sets out to provide its owner with a comprehensive look at the Scottish earthmovers scene, and it will be of interest to enthusiasts, owners, drivers, and site managers worldwide.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 421

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

EARTHMOVERS IN SCOTLAND

Mining, Quarries, Roads & Forestry

David Wylie

Contents

Foreword

Heavy machinery plays a key, but often hidden, part in all of our daily lives. From the roads we drive on to the paper this book is printed on, the supply chain from raw material to finished product involves some of the most technologically advanced equipment on the face of the Earth.

This book provides a snapshot of some of the machinery used across many of Scotland’s industries. As such, it provides a unique record of our industrial heritage that, I have no doubt, will be seen by future generations as a historically important document.

I also hope that this publication inspires the current generation of children and young adults to look towards the many aspects of the machinery industry as a worthwhile career. From those who would prefer practical work outdoors to the academically gifted, there are exceptional opportunities; not only for a lifetime of rewarding employment, but also to work with some of the most inspiring and humorous characters that one will ever have the pleasure to meet.

Graham Black, Editor: Earthmovers Magazine. June 2016

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank many people who provided me with the necessary opportunities, help and support, and who encouraged me to pursue a career in photojournalism.

My interest and development in photography increased rapidly by attending lectures presented by Neil McKellar, a lecturer at Glasgow University. Neil asked us to study – among other things – the old masters of painting in order to understand the use of light and composition to help us capture the subject matter in a powerful image. Thanks also to the rest of the class of 1989–1991 for their friendship, help and advice.

Due to work and family commitments, I gave up photography for a number of years and returned at the start of 2009, with a small digital compact camera that my wife bought me as a present. I soon started visiting various construction sites, mostly beyond the site perimeter, and started uploading my earthmoving images to the photo sharing website Flickr.

That is when a ‘sliding door’ moment occurred, as Janie Manzoori-Stamford, Contract Journal (CJ) online content and community editor and Flickr member, invited me to enter a competition in the magazine. I picked a few of my best images and went out to capture something that fitted the theme – earthmoving. I was delighted to win the competition. CJ also had a picture page on its website and a photo of the week running in the publication. Janie’s colleague, Will Mann, CJ web editor, gave me editorial rights to upload my construction images to the magazine’s website. Will also gave me my first opportunity in photojournalism, as he arranged a visit and published my first feature, in October 2009, about a large surface coal mine operating 320-tonne Liebherr R9350 excavators at Broken Cross, owned and operated by Scottish Coal.

As well as my activity with CJ; Graham Black, editor of Earthmovers Magazine, started to publish my images from June 2009 in the readers’ section of the monthly title. However, my big break in photojournalism came when Graham and I met at the biannual ScotPlant show in Edinburgh during April 2010, to discuss a possible part-time freelance role for Earthmovers. Graham showed a great deal of faith by allowing me to return to Broken Cross to report on one of the biggest stories of the year in Scotland – the delivery and operation of ten new 136-tonne capacity Caterpillar 785D haul trucks; the deal was worth £23million.

I would also like to thank Peter Haddock (of Edson Evers PR), Paul Argent and Keith Haddock for their help, support and advice – and the occasional image – over the years to support some of my features, and to the other Earthmovers journalists and the production team that helps to edit and present my work to the readership in the best possible light.

A special thanks to all the owners, operations directors, plant and site managers, press officers, media contacts, drivers and owner drivers, the original equipment manufacturers and their dealers, for their technical information, machine brochures and support. Without everyone’s time and commitment, we could not have brought you this book.

Many thanks to Terex’s marketing team of Caronne Lockhart and Lyle Sibbald for their extensive trawl through the archives and to the editor of Blackwood Hodge Memories website and to Keith Haddock for supplying some of the images and details used in the chapter on the history of the Terex factory at Motherwell, and for the use of Eric C Orlemann’s book, Euclid and Terex Earth-Moving Machines, as an invaluable research tool. Thanks also to Nigel Rattray for kindly providing some images of Terex machines and of the Demag H485 face shovel. And a special thanks to my daughter, Gillian, who helped with interviews, researched material at the Terex factory and co-authored this particular piece.

The first image published was of my award-winning photo of a CASE CX210 for Contract Journal. The image was taken for its competition – best image with an earthmoving theme. The machine was working at Newhouse, just a few miles from my home in Lanarkshire, and the driver kindly helped to pose the falling earth from the bucket.

Thanks to Gordon Dallas and Stephensons Photographic, Newton Mearns, Glasgow, for the fine work in restoring and making digital images from some of the historic photographic prints found in the mining chapter of this book.

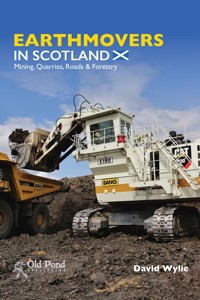

Special thanks to Harry Banks OBE, chairman of the Banks Group, for allowing me to use one of his new mining shovels as the front cover image, and to some of his management team, comprising of Jim Donnelly, Robbie Bentham, Derek Robson, Neil Cook, Ian Ritchie and Darren Banks, for all their support and a warm welcome during multiple visits to their surface mine operations.

Thanks also to Kevin Henderson, Marubeni–Komatsu Ltd, lead field service technician and his team for looking after me over a number of days and a special thank you for supplying some of the images used in the PC2000-8 face shovel assembly chapter.

Thanks to Rachel Turner, commissioning editor, at Old Pond/5M Publishing, who spent hours reading and providing invaluable feedback on my work and also to Alessandro Fratta Pasini, assistant editor; Denise Power, production manager; and Katrina Cacace, marketing and all the other staff at 5M publishing and Old Pond for publishing my book.

Last, but not least, a very special thanks to my wife, Fiona, for her unwavering support, as well as proofreading my draft reports, and for reigniting my interest in photography by buying my first digital camera and my SLR film camera back in the late 1980s. And to my two daughters, Gillian and Emma, for their love, and understanding for my interest and passion for all things diggers!

First published feature. This image was printed on the front of my two-page report for Contract Journal in October 2009 – the massive 320-tonne Liebherr 9350 backhoe at Broken Cross surface mine.

Introduction

From an early age I recall my late father, Sam, working for AV Wilson plant hire in Motherwell as a 360 excavator operator and then for Hewden Stuart Group following a takeover of AV Wilson’s business. I also remember him working on his Hymac 580C excavator carrying out general maintenance duties in AV Wilson’s yard in Mill Road. That’s what operators did then, and some still do now, when off-hire, which wasn’t very often in my father’s case as he was an excellent operator by all accounts. He could keep the machine on-hire for long periods of time by keeping the site manager – who signed off his weekly hire log – happy by working to a high standard.

He started operating Caterpillar’s first 360 machines, in the form of, 215, 225, 235 and 245 excavators, when he moved across to work for Hewden and had worked on some of the biggest projects in Scotland, such as the Megget Reservoir, which is a man-made reservoir in Ettrick Forest, in the Scottish Borders.

Due to my father’s work, I was always fascinated with plant and machinery, and was an avid reader of the weekly publication Construction News, in particular the section on plant and machinery. I have lasting memories of the large machine adverts that were inserted into the paper during the early 1970s and 1980s. It is fair to say that those big A3 and A2 format fold out glossy posters – from JCB and other manufacturers – still influence some of my photographic captures today and the layout of this book.

As a freelance photojournalist and Scottish correspondent for Earthmovers Magazine, I feel privileged to have access to the latest earthmoving machines and technology that are designed to power and control these machines to be the most productive and fuel efficient mobile plant ever made. Some machines featured in this book are record breaking for their time or the first of their kind anywhere in the world.

This book covers numerous site visits across four key applications – mining, quarries, roads and forestry – and I want to share these experiences through not just my own eyes, but also the views of highly skilled and professional people that I have met along the way. I will travel to all four points of the compass across Scotland, to explore the diverse work and visit machines that help to produce energy, everyday products and materials, and support the building and repair of the country’s transport network.

For example, a visit to a silica sand quarry reveals the raw materials to make glass that bottles Scotch whisky. And I visit hard stone quarries, where basalt rock is blasted and crushed to protect us from the forces of nature (armoured stone) and to help build sports grounds and provide wear resistant road surfaces. Granite quarries produce red stone for paths, driveways, and high grade rail track ballast for goods and passenger trains to run on. Limestone is extracted to make cement products to build homes, offices and massive road and rail bridges. Surface coal mines help to keep the lights on, as 35% to 40% of our electricity is still generated using this source of fuel. And you may be surprised to know that more than 60% of all the timber produced in the UK is grown and harvested in Scotland.

I have had the pleasure of visiting some of the largest earthmovers in the UK, such as Caterpillar’s D11R bulldozer and Liebherr’s massive 320-tonne R9350s. On a visit to Banks Mining in West Lothian I was invited to hop a short distance over the Scottish border to see surface mine restoration work and the largest hydraulic excavator still working in the UK – the mighty 520-tonne Q&K RH200 at Shotton surface mine in Northumberland. At the other end of the scale, I take a look at a special 1.6-tonne mini digger and its owner operator, as well as manufacturing of mining equipment here in Scotland.

JCB entered the tracked loader market with the 110 in 1972. An example of a large format fold out glossy poster – from JCB and other manufacturers – that influences some of my photographic captures. Photo: JC Bamford Excavators Ltd

I’m grateful to my hosts, as without their help I would not be able to safely capture some of the close-up action shots found in this book. And I try not to produce just record shots of the machines working, as each one is carefully composed to capture them in their operational setting, and show the power and action of each machine type.

And while there have been a number of high quality books covering earthmoving machines operating in England and Wales, this book sets out to provide a comprehensive look at the Scottish earthmoving scene, with some of the most powerful images presented in large double page format, with incredible detail to help you get close to the action. I hope you enjoy this book as much as I did gathering the material and writing it.

Much of the preparation for this book was done in the run-up to and aftermath of the 2016 event at Bauma, where one of the star attractions and my assignment for Earthmovers Magazine’s July issue, was to cover the 691-tonne Komatsu PC7000-6 face shovel at the show. The exhibition is held in Munich every three years, and attracted 580,000 visitors over seven days. This was up by 60,000 from the last event in 2013 and is a good indicator of how popular this subject now is. I couldn’t resist including one or two pictures of the star attraction here. But sadly these pictures were not taken in Scotland or anywhere remotely near it, so although I have many more, I will have to save them for a future book and can only hope a PC7000 will one day find its way to a site here soon or that I see one in action elsewhere in the world!

The largest hydraulic excavator ever to have been displayed at Bauma, Komatsu’s new 691-tonne PC7000-6 Super Shovel.

Spacious operator’s cab with the driver’s seat mounted in the centre, machine performance LCD screen on the L/H side, a 360 degree camera system screen at top right and Modular’s ProVision GPS machine guidance system screen bottom right.

Mining

Since 2010 I have been fortunate to visit a number of Scottish surface mines to cover different manufacturers and types of excavators, from Liebherr’s massive 320-tonne R9350, O&K RH120-C and E models, Komatsu PC3000s and the forerunner to this machine, the Demag H255S, to smaller machines, such as 20–30-tonne Cat, Volvo and Hyundai coal shovels and dump trucks; the 138-tonne payload Cat 785Ds to 50-tonne payload Bell B50D and large bulldozers from Komatsu and Caterpillar.

I’ve included two surface mines that I didn’t have the opportunity to visit on site, the first chapter covers J Fenton & Son machines working at a fireclay and coal mine at Bathgate in 1994. It was there where I was able to catch my first look, standing at the perimeter, at a massive RH120-C face shovel loading Cat 777 rigid dump trucks and have been fascinated with large mining machines ever since.

I enjoyed working with my daughter, Gillian, as we covered the history and significance of the Terex factory at Motherwell, which has been producing some of the most iconic earthmovers ever made since it opened in 1950.

Scotland has held a few records and operated some of the first machines in their class within the UK’s opencast coal sector. I read with interest that Westfield opencast mine near Kinglassie in Fife was reputedly the largest opencast coal mine in the UK with some 26 million tons of coal extracted between 1961 and 1986. It was also claimed to be Europe’s deepest mine, at 850ft below ground level at its deepest point. This and more detailed information can be found in Keith Haddock’s fantastic book – British Opencast Coal: A Photographic History 1942–1985.

The year 1986 was also a significant one for the Scottish opencast coal scene, as the world’s largest hydraulic excavator arrived at Coal Contractors Roughcastle coal mine, and with that in mind I was determined to include it and operational details of the site. Information and photographs of this site are scarce; however, I was able to obtain images of it working from Nigel Rattray and Komatsu Mining Germany and detailed knowledge of the site from Derek Taylor, who worked at Roughcastle as an O&K RH9 coal scraper operator.

I was also fortunate to visit at a time when coal prices allowed surface mining companies to make significant investments in new kit, such as Scottish Coal’s R9350 excavators and Cat 785D trucks, ATH’s five-strong fleet of Komatsu PC3000-6s, and Land Engineering Services 50-tonne Bell B50D trucks used as the site’s prime movers. However, towards the end of 2012, some long-established names hit economic headwinds with the slump in world coal prices and high cost of fuel, and they unfortunately went into administration. Scottish Coal and ATH assets were subsequently bought by Hargreaves Services to keep the sites open and carry out restoration work.

That said, Banks Mining bought a new Cat 6030 and Komatsu HD785-7 haul trucks for its Scottish Rusha surface mine in 2012 and at the start of 2016 made a £3.5 million investment in an additional 520-tonne RH200 face shovel, Cat coal trucks and JCB excavators at its Shotton operation.

Once coaling operations come to an end, mining companies are duty bound to restore the site to its former glory or, some cases, leave the land in a much better state than they found it before mining operations started and I have included a number of sites restored to an exceptionally high standard in this chapter.

CHAPTER 1

J Fenton & Son • Northrigg Opencast site Bathgate • October 1994

As my interest in photography took off in the late 1980s I did not have the same access to sites then, as I do now, as a freelance photojournalist and Scottish correspondent for Earthmovers Magazine. However, during October 1994 I discovered an opencast site a short drive from my home, next to the A709 road between Armadale and Bathgate – just off Junction 4 of the M8 motorway between Glasgow and Edinburgh – in central Scotland.

Photograph taken standing at the side of the A706 near J4 of the M8 motorway at Bathgate during October 1994 with clear view into the dig area.

Using my first SLR camera, a Canon EOS600, with a roll of Kodak film and fitted with a long focal length 70–210mm lens, I was able to capture my first shots of a huge mining excavator and haul trucks in the shape of two legendary machines of surface mining in the UK – The mighty O&K RH120-C mining excavator and Cat 777C haul truck models. Standing at a low boundary fence, on a grass verge at the side of the A706, I had a clear line of sight into the dig area. I was also fortunate in as much that it must have been early on in the operation, as no perimeter mounds had been built to screen the site. At that time I was happy with my photographs and left with no details about the mining operation. And in reviewing some of the images used for this piece, I was reminded of how modern full-frame digital cameras, fitted with a professional lens, have transformed our ability to produce high quality images with little or no grain – even in low light – as published in the rest of this book.

The O&K RH120-C has a large operator’s cab in keeping with the proportions of the machine and the large front screen provides a good view of the dig area.

Roll forward 22 years; I decided not to sit on these unpublished images any longer and to make them my opening section of this book on mining. However, I now found myself with a challenge of obtaining detailed information about the site. My research for more information lead me to West Lothian Council archive department in Livingston, where I was able to access historical documents, such as planning applications. More than anything else, the large storage box was full of numerous files on environmental impact studies, details of restoration bonds (which is usually a substantial sum of money deposited, as insurance, in case the operator fails to restore the site) and restoration plans.

Initially I thought I would be looking for an opencast coal operator as all I had to go on was the name Fenton displayed on the side of the machines, What I actually found in the files was a brickworks company that had been responsible for the site, and I must congratulate the council staff for being able to locate this archive material with very limited information provided in my request to look at the file they held.

This area can trace its history back to 1859 when John Watson of Glasgow bought the Bathville site in Armadale and shortly after built brickworks to use the local fireclay being mined along with coal. The brickworks changed ownership – and name – many times over the last 100 years, and at the time of my visit it was owned and operated by United Fireclay Products Ltd, who had made the planning application for the Northrigg Opencast site and at the time operated a series of sites in central Scotland.

The 148ha Northrigg Opencast site had been split into a number of different phases and progressively restored. There were also a number of different contractors hired to work these phases to extract and transport some 250,000 tonnes of clay to its sister brickworks (Armadale Brickworks) nearby using the site’s internal haul roads. They extracted around 700,000 tonnes of coal, and this was transported by heavy goods vehicles by road. Records also indicate that the average number of heavy goods vehicles entering or leaving the site was 25 per day. However, due to customer requests by some of the local power generation companies asking for three weeks of coal supply in one day, up to 125 vehicle movements could be required per day with subsequent reduced traffic movements thereafter.

Extraction of both clay and coal also resulted in the moving of some 20 million tonnes of overburden during its eight years of operation – from 1991 to 1999. Records show RJ Budge – which became UK Coal – worked on phase one, which was completed ahead of schedule in the spring of 1994. At the time of my visit in October 1994 it was J Fenton & Son, based in Perth, that was working on the next 42ha phase, referred to as Northrigg Phase W on the planning application documents.

The Armadale and Bathgate area is well known for its coal mining activates, by both surface and underground extraction methods, to reach geological deposits laid down some 500 million years ago. A letter on file stated there had been past underground workings; one seam of Ironstone had been extracted from depths ranging from 220m to 530m until 1955, one seam of fireclay had been mined at a depth of 80–90m, with the last date of extraction being 1919, and seven seams of coal to a depth of 560m being worked until 1967. All these seams were in the vicinity of the site and where you find coal you will usually find clay.

The term ‘fireclay’ was derived from its ability to resist heat and its original use was in the manufacture of refractories for lining furnaces. However, it is also used in the manufacture of hard-wearing engineering and facing bricks for house building and other construction projects.

As an aside, fireclays are sedimentary mudstones that occur as ‘seatearths’ underlying almost all coal seams. Seatearths represent the fossil soils on which coal-forming vegetation once grew and are distinguished from associated sediments by the presence of rootlets and the absence of bedding. Fireclays are mainly confined to coal-bearing strata and are commonly named after the overlying coal seam. The production is, therefore, closely related to opencast coal extraction; the seams are typically thin, normally less than 1m, and rarely more than 3metres.

The earthmoving machines I photographed in October 1994 comprised of a 260-tonne RH120-C mining face shovel and a fleet of four Caterpillar 777C haul trucks. The C model truck was launched in the same year, had a payload of 86 tonnes and was powered by a 34.5 litre 870hp V8 turbocharged after-cooled diesel engine. The Cat D9N bulldozer on site was fitted with a single-shank ripper attachment at the rear and an agricultural tractor pulling a fuel bowser. It is a set-up that is not that dissimilar to that operating today in most surface mines, albeit the machines’ model numbers may have changed and the kit is far more hi-tech, running clean-burn engines fitted with electronic control systems for both the engine and hydraulics.

In 1994, the RH120-C on site looked like new, but having tracked down some people managing the plant during this time, I discovered this machine was purchased from another operator in Germany. It came with a large 12-tonne steel ball as it had been on quarry operations and was required to extract material and break the oversized rocks by the method called drop-balling (which will be covered in more detail within the quarry chapter – at Dunbar cement works – later in the book). Some of the 777C’s haul trucks looked factory fresh, but in fact had been redeployed, from East Chevington opencast coal site in Northumberland, which closed in 1994, to Bathgate. I feel it’s fair to say that J Fenton & Sons and its team kept the machines looking and working in tip-top condition.

The bucket sizes on the RH120 series of machines has steadily crept up over the years as engine and hydraulic power has increased and frame design has evolved. The current incarnation is the 300-tonne Caterpillar 6030, is able to handle a 17 cu.m bucket. However, I believe in 1994 this RH120-C would be swinging a 13 cu.m bucket and would be a perfect match to fill a Cat 777C haul truck in four quick passes.

The Cat D9N dozer was observed carrying out three main duties; pushing material over the edge of the overburden tip site, helping to keep the haul road in a smooth condition – to save on haul truck tyre wear and fuel burn – and lastly tidying up in and around the loading area of the haul trucks. The reason the loading area needs constant attention from the D9N driver – to remove large rocks – is to minimise damage to the large and expensive tyres.

One Cat 777C is receiving the last pass, as the other 777C is waiting to reverse into the spotting area as soon as possible, in order to keep the big O&K prime mover productive at all times.

Cat D9N on the top of the overburden tip site area.

The first of four passes into the back of the Cat 777C skip.

Fenton kept its kit in good order, however, the single grouser track pads on this D9N look a little worn.

The fuel bowser on its way to refuel the RH120-C prime mover during a planned rest break.

RH120-C has the unique O&K Tri-power system fitted to the boom and connected to the bucket to improve digging and load performance.

The planning application for Northrigg Phase W indicated that there were geological problems encountered in Phase one of the site due to glacial action that had disturbed and broken the upper strata, making the extraction of uncontaminated materials difficult. Northrigg Phase W was divided up into three cuts and records show that Cut A, in the south-west section, was the first area to be worked to extract the upper levels of high quality clay and coal. Drill holes indicated that Phase W was situated in reasonably good and level strata, which were dipping north-west at an angle of just four to six degrees and with only minor evidence of glacial disturbance compared to Phase one.

Due to time, cost and efficiency savings, opencast operations, or as they are now referred to as surface mines, are worked by making what is known as a box cut to start the extraction process. Once the topsoils have been removed, the initial box cut can be made and the soils and overburden from it are stored away for reinstatement at the end of operations – this allows the cut void to be progressively restored by backfilling the worked out areas as the box cut moves forward.

Having revisited the exact spot 21 years later, it is hard to believe that the beautifully restored landscape in front of me was once a 40–50m deep hole in the ground with a monster mining shovel, 86-tonne capacity haul trucks and large bulldozers working hard to extract fireclay and coal.

The phased extraction has allowed the development of a sympathetic and regenerated landscape. And possibly without the opencast operation, this may not have changed an otherwise unmanaged, partly industrially degraded landform into a visually acceptable greenspace for future generations. The restoration of surface coal mines is still an important aspect of this industry and will be touched on again in different site visits throughout the mining chapter of this book.

Taken during Oct 2015, 21 years later. It is a nice restoration job, as the RH120-C would have been removing overburden back in 1994, just in front of where a lake has been created to help wildlife to flourish.

CHAPTER 2

Scottish Coal • Caterpillar 785D mining trucks • Broken Cross • June 2010

Scottish Coal was one of the largest surface coal mining companies operating in Scotland and the UK when it took delivery of ten Caterpillar 785D haul trucks at its Broken Cross surface mine. The 785D mining trucks were the first 785s to be sold in the UK for some 15 years. Suffice to say, Finning was extremely pleased at the time to have secured an order for this size of mining truck once again.

On my first assignment representing Earthmovers Magazine, I was invited to the official launch event, as the 785Ds trucks were part of a large modernisation programme worth £45 million that started in 2008. Finning (UK) Ltd, Caterpillar’s distributor in Great Britain, had supplied some 125 pieces of Cat mining equipment under this programme; the Cat 785Ds deal alone was worth £23 million for the ten mining trucks with a seven-year/36,000 hour repair and maintenance (R&M) equipment support package included.

Broken Cross is situated close to the M74 in South Lanarkshire, Scotland, and the opencast coal mining site covered an area of 610ha, where some 244 million cu.m of overburden was being removed to allow the recovery of 12.8 million tonnes of high quality coal from Scotland’s biggest surface mine. The excavation will be 168m at its maximum depth.

The site was mothballed for a time – affected by low coal prices – before recommencing in August 2008. Around 48 million cubic metres of material has been blasted so far at a rate of 400,000 cu.m a week, with some 18,000 tonnes of coal being recovered each week. The new Cat 785Ds are part of a huge earthmoving fleet that is run by Castlebridge Plant, a plant hirer owned by Scottish Resources Group, the parent company of Scottish Coal.

The heavy duty overburden removal is handled by five large 320-tonne Liebherr R9350 hydraulic excavators – the first and only examples found in the UK – which are ideally matched to the new Cat haul trucks with a 136 tonnes payload capability. Scottish Coal invested in the 785Ds to make significant efficiency gains throughout its operations at Broken Cross to achieve the lowest cost per tonne, as well as getting the maximum productivity out of these large hydraulic excavators.

The R9350s are also loading a fleet of more than 40 91-tonne payload haul trucks, such as Cat 777F and Terex TR100, (the Terex trucks are built just 30 miles from the site at the Motherwell factory, further details are covered later in this book) in three passes using their 17 cu.m buckets – three R9350s are operating in backhoe and two in face shovel configuration. During our visit we were invited into the cab of the R9350 face shovel and the operator commented on the ease with which he can load the 785Ds as they present a much larger target area, with a significantly wider dump body skip, in comparison to the 91-tonne class haul trucks, resulting in faster cycle times as the operator can be less precise in placing the excavated material into the truck body.

The R9350 operator was loading the big Cat trucks in five quick passes; however I also observed the R9350 excavator working just that bit harder in trying to turnaround the small queue of mining trucks that was starting to form when a team of 785DS were waiting to be loaded.

Finning had carried out an extensive array of modification to meet Scottish Coal’s needs. By listening to and working with the highly experienced management team, a number of important changes were made, such as moving the trucks’ front isolator control panel from the right-hand side to the driver side on the bumper section. The reason for doing so was to improve operational safety; by repositioning the control panel into the driver’s view, similarly the fast-fill fuel coupling (567 litres/150 gallons per minute) is placed adjacent to the isolator switch so that when refuelling is carried out the driver has direct view of the operation. In essence, they are trying to engineer out the risk of the truck accidently being driven away, just one of many modifications under a safety first approach.

The 785D delivers another load to the tip site. Note the R9350 in background where this truck had just received its load.

The 785D waiting to be loaded. Note the size of the 17 cu.m bucket hitting a smaller target of the Cat 777F’s 91-tonne capacity skip.

A Cat 740 articulated dump truck fitted with an adapted coal body hauling the ‘black gold’ to the coal stockpiling area.

Driver’s work station/spacious safety cab. Note the sport car-size steering wheel to operate a massive 250-tonne haul truck. The Caterpillar LCD camera monitor system provides a good view of the rear & offside front wheel station blind spots.

With safety being the number one priority in any mining operation, Scottish Coal asked Finning to modify the standard mirror package. Again Scottish Coal was very specific about having an effective all-round visibility package on its new trucks, and the Finning team delivered by removing the standard large one-piece 785D mirror units and replacing them with two Cat 777F mirrors, two on each side of the truck. Not only could these be individually angled to cover rear-view issues, but it also meant the gap between the mirrors gave some degree of forward and side visibility. An additional benefit to fitting 777F mirror units meant that they could be heated, which is particularly relevant to working in the Scottish climate!

Operating such a large mining truck as the 785, three close proximity mirrors are also fitted (driver’s side, centre, and offside, all mounted to the front guard rails), giving the driver good visibility to the front of the truck. Even with people standing right next to the front bumper they can be easily seen in the mirrors. Finning also supplied and fitted the Caterpillar product camera units, linked to a two monitor system in the cab that covers the offside front wheel station area, rear-view areas; these units are high resolution LCD screens that give the driver a bright clear view of the main blind spots.

At the time, Scottish Coal’s MD, Andrew Foster, commented: “The Scottish Coal team have worked closely with Finning to produce a visibility package on the 785D to an industry leading standard. By inspecting the trucks early in the build process we were able to identify simple modifications to make a good truck even better. The safety and comfort of our workforce is our number one priority.”

Another bespoke modification was to move the lights out of the front bumper panel area and reinsert them into the engine radiator grille, as UK mining operators tend to park the truck’s bumper against a purpose-built mound to allow the drivers to safely step off the trucks during any breaks or shift changes. This is a good illustration of Caterpillar’s original design being modified to meet UK market needs by the local Caterpillar dealer. Clearly, if the lights had not been repositioned it would have resulted in impact damage, Scottish Coal also asked Finning to install the fire suppression equipment at bumper level for ease of maintenance.

One of the technical specifications that differs on this class of Caterpillar mining truck from a 777F is the rear axle. Differential and hub reduction gears are fed by a new drive pump system providing continuous filtration and spray lubrication to these components, which means less down time due to longer drain intervals and improved component life. The 785’s dual-slope body design was also given a bespoke wear liner package by the Finning team, using Hardox steel plates cut to Finning’s own specification templates, to further increase the durability of the truck.

Finning states these trucks are built to be rebuilt, with a planned overhaul at 20,000 hours scheduled and regular oil sampling carried out as part of the periodic maintenance schedule to ensure maximum component life and to detect small problems before they become more expensive ones. In addition to this, Caterpillar’s VIMS monitoring system provides critical payload information to the operator and Electronic Technician, or ET in Cat speak (Cat’s service tool), data to service personnel at Finning’s Glasgow Branch. Finning has a shared financial interest in ensuring maximum uptime for the trucks. While it is early days, the 785s are currently running at 98% availability. Furthermore, they have evidence of Finning’s ‘lastability’ programme working, whereby some B model 777 haul trucks with more than 60,000 hours and having been rebuilt three times were running at 95% availability.

As part of the equipment deal, Finning are also supplying driver training to Scottish Coal’s staff, using the instructor seat, which is fitted as standard equipment. Access up to the cab area is via a new step design, over the older 785C model, which is mounted diagonally across the front of the engine radiator resulting in a less steep and safer stepladder arrangement, with cab access into the instructor seat via a separate right-hand side door.

Cat 785D chassis at Finning’s Glasgow depot in the early stages of assembly; note the original headlamp position in the bumper.

Dual-sloped mining body, with Hardox liner/wear plates fitted. Finning also repositioned the headlamps from the bumper to the grille area. The truck’s isolator control panel and fast-fill fuel coupling were grouped together and moved closer to the driver front window – seen just below the red fire suppression equipment, which was fitted on the bumper top panel for ease of maintenance.

Cat 785D being loaded with overburden by a 320-tonne Liebherr 9350 face shovel.

A Liebherr R9350 loading a Cat 785D haul truck in five passes. Note the tip site in the background.

The instructor seat also provided me with an opportunity to experience first-hand the performance of this large mining truck. The first thing that hits you is the sheer size of the truck, a rise of some 5.67m from the ground to the canopy, operating width of 7.06m, a wheel base of 5.18m and overall length of 11.54m. At this point you can fully understand the reason why an uprated mirror and visibility package was specified. Once settled into the comfy seat, I found the cab to be spacious, and having good all-round visibility with a large glass area and safe ROPS/FOPS five-sided protected work station, with the driver enjoying a comfortable air suspension seat with integral three-point seatbelt. Although the driver’s seat has air suspension, the massive size of this truck means it copes extremely well with the haul road that was in less than perfect condition due to adverse weather conditions. The driving and ride experience was one of total comfort, which can be attributed, in part, to the large size and weight, road wheel, and not forgetting the truck’s nitrogen-filled suspension units.

Trying to keep the haul road in good condition is hard work with the amount of rainfall Scotland receives. That said, Scottish Coal deploys a number of machines to constantly deal with this issue – a large and highly mobile Cat 834H wheeled-dozer, a Caterpillar grader and a number of Cat D9T dozers all help to keep the haul road surface in tip-top condition.

The 785D is powered by Caterpillar’s 3512C HD 12-cylinder, four-stroke engine design that is Tier 2 compliant and which produces a very impressive 1,450hp. Given that the all up gross weight is some 250 tonnes, this power unit provided smooth continuous power throughout the rev range, both in pulling away fully loaded and on the ramps to the tip site areas. During my time in the cab, Caterpillar’s six-speed mechanical transmission provided smooth gearshifts with the driver, leaving the gear selector in sixth gear position for forward travel throughout the trip, with the automatic gearbox clearly helping to reduce the driver’s workload.

The driver commented that he was delighted to be assigned to a new 785D, having previously operated one of the 91-tonne class haul trucks, and having only operated the truck for a few days he has a very clear opinion that the 785D has superior ride quality, pulling power, low noise levels and a lack of shock loading/movement when being loaded by the big Liebherr’s 17 cu.m bucket. It is worth noting that the driver also feels that it’s ‘his’ 785D, as he shares the truck with only one other driver, (during two 12-hour shifts) which helps keeps the cab interior clean and both of them driving it with mechanical sympathy, which makes sense on a vehicle with a price tag of £1.2 million per truck. Regardless of this arrangement, as mentioned previously, Finning and Scottish Coal would soon know if the truck was being driven incorrectly, via a data satellite up-link, and with the information from the Cat VIMS and ET monitoring systems providing both parties with valuable management information.

Finning UK had further supported Scottish Coal’s investment in Caterpillar equipment by providing no fewer than 14 Caterpillar-trained engineers dedicated to their operation. These included four engineers working at Broken Cross – on a 12-hour shift basis – with two engineers on day shift and two on night shift duties, to cover the 24-hour mining operation. During our visit there were a number of extra Finning engineers on site putting the finishing touches to the 785s, including mounting the body to the chassis.

The build process was carried out at two main Finning dealership locations, with the dual-sloped specification truck bodies being built in Finning’s HQ at Cannock and driven to Broken Cross for final assembly. The 785D chassis was assembled at the Glasgow branch from four individual articulated lorry loads driven from Liverpool docks, having first travelled across ‘the Pond’ from various plants in America. Some 250 man hours were spent assembling/modifying each truck, which included a final coat of new Caterpillar yellow paintwork at the Glasgow branch. Finning UK invested in a new spray paint booth to accommodate equipment as large as the 785D. The new paint booth, along with four extra service bays and open-plan office space designed to improve inter-departmental communications, was part of a £1.2 million investment by Finning at its Glasgow branch.

Everyone was hoping that this substantial investment would help secure the site’s long-term future and I was looking forward to a follow-up visit on the trucks and the site progress. However, with the worldwide slump in coal prices again and higher operating cost – including rising fuel prices – Scottish Coal was put into administration during April 2013. Durham-based Hargreaves Services invested £8.4 million to buy some assets from KPMG, the liquidators of Scottish Coal, to take ownership of the five mines, including Broken Cross in South Lanarkshire, House of Water and Chalmerston in East Ayrshire, St Ninian’s in Fife, and Damside in North Lanarkshire. The £8.4 million sale covered much of Scottish Coal’s property portfolio, including 30,000 acres of land, together with assets owned by Castlebridge Plant, along with site restoration undertakings, leading to a saving of 500 jobs.

Castlebridge Plant and Finning staff inspecting the latest truck to be completed, which clearly shows the size of this massive mining truck.

Broken Cross is a vast site and the largest in Scotland producing 1 million tonnes of coal per annum. Look top left to see how small a massive 320-tonne R9350 mining shovel appears in comparison.

A Cat D9T on coal stockpiling duties near the entrance of the mine.

The large, powerful and highly mobile Cat 834H wheeled dozer is tidying up the loading area.

CHAPTER 3

ATH Resources Plc • Komatsu PC3000-6 • Glenmuckloch • March 2011

ATH Resources Plc had invested in five 260-tonne Komatsu PC3000-6 Super Shovels over a five-year period and I went to their Glenmuckloch surface mine operation to enquire how these large German-built hydraulic excavators were coping in the surface coal mines of Scotland.

Glenmuckloch surface mine is near Kirkconnel village, in the Dumfries and Galloway region, and is set back about 1.5 miles from the A76. The site was acquired from Scottish Coal in June 2005, along with the Grievehill site, with an estimated coal reserve of 2.8 million tonnes. The mine commenced operations in the summer of 2006 and started producing coal in September the same year. All coal production from Glenmuckloch is transported to ATH Resources’ Crowbandsgate railhead via a 12.2km overland conveyor, known as The Lochside Runner, which is the longest of its type in Europe and can transport up to 500 tonnes of coal per hour.

The Lochside Runner overland conveyor transported coal to Crowbandsgate railhead. It is a distance of 12.2km, which is the longest conveyor of its type in Europe and can transport up to 500 tonnes of coal per hour.

At the start of excavations in 2006, ATH Resources deployed new PC3000-6 Super Shovels and an O&K RH120C and two Terex/O&K RH120Es, the O&K RH series machine being redeployed to the new Netherton surface mine in Cumnock, East Ayrshire, at the start of 2011 – a site that will be covered in full later on in this chapter.

One of six new Cat D9T dozers purchased by ATH. During the visit I spotted a pre-production Cat 777G model on field trial, which Caterpillar calls a ‘field follow’ machine. Note the strata starting to go vertical on the top benches.

The three Komatsu PC3000-six models operated at Glenmuckloch can trace their DNA back to the Demag H255S, the prototype H255S being operated at ATH’s Skares surface mine and still going strong with some 40,000 hours on the clock. The main production of Komatsu large mining shovels, from the PC3000 to the mighty 720-tonne PC8000, are built by Komatsu Mining Germany GmbH (KMG) at the former Demag factory in Düsseldorf, Germany. ATH’s machines were sold and are supported through UK-based KMG Warrington.

Part of our visit was timed to coincide with ATH’s planned maintenance tasks during Saturday afternoon when the sunshine miners finished for the day. The on-site maintenance team at Glenmuckloch are highly experienced and with a wealth of knowledge of these large mining machines. They refer to the Demags affectionately and speak highly of these monster shovels.

Stuart Bickley, maintenance foreman on site, has nothing but praise for the PC3000s due to their ultra-reliable performance and said: “These excavators can be very reliable and can go days without putting a spanner on them, except for routine maintenance, and are achieving 99% availability. However, the same cannot be said for some competitor machines, which in our experience are higher maintenance.”

Stuart comments further: “I have one fitter to look after the three PC3000s, but would require a fitter for each of the other non-Komatsu mining shovels to keep them serviceable.”

Doug Hogarth (chargehand) is Stuart’s right-hand man and echoes Stuart’s feelings towards the three Komatsu PC3000s. Doug said: “We have enjoyed really good up-time with these machines over the past five years, with no major issues and there have been no cracks on the stick, boom, or undercarriage.” Doug was quick to point out: “Even some of the main hydraulic hoses on the five-year-old (Fleet No. 3) machine, with 24,000 hours on the clock have not been replaced.”