Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Tacet Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Essential Novelists

- Sprache: Englisch

Welcome to the Essential Novelists book series, were we present to you the best works of remarkable authors. For this book, the literary critic August Nemo has chosen the two most important and meaningful novels ofHall Cainewhich areThe Manxman and The Prodigal Son Hall Caine's popularity during his lifetime was unprecedented. He wrote fifteen novels on subjects of adultery, divorce, domestic violence, illegitimacy, infanticide, religious bigotry and women's rights, became an international literary celebrity, and sold a total of ten million books. Novels selected for this book: - The Manxman - The Prodigal Son This is one of many books in the series Essential Novelists. If you liked this book, look for the other titles in the series, we are sure you will like some of the authors.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1734

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title Page

Author

The Manxman

The Prodigal Son

About the Publisher

Author

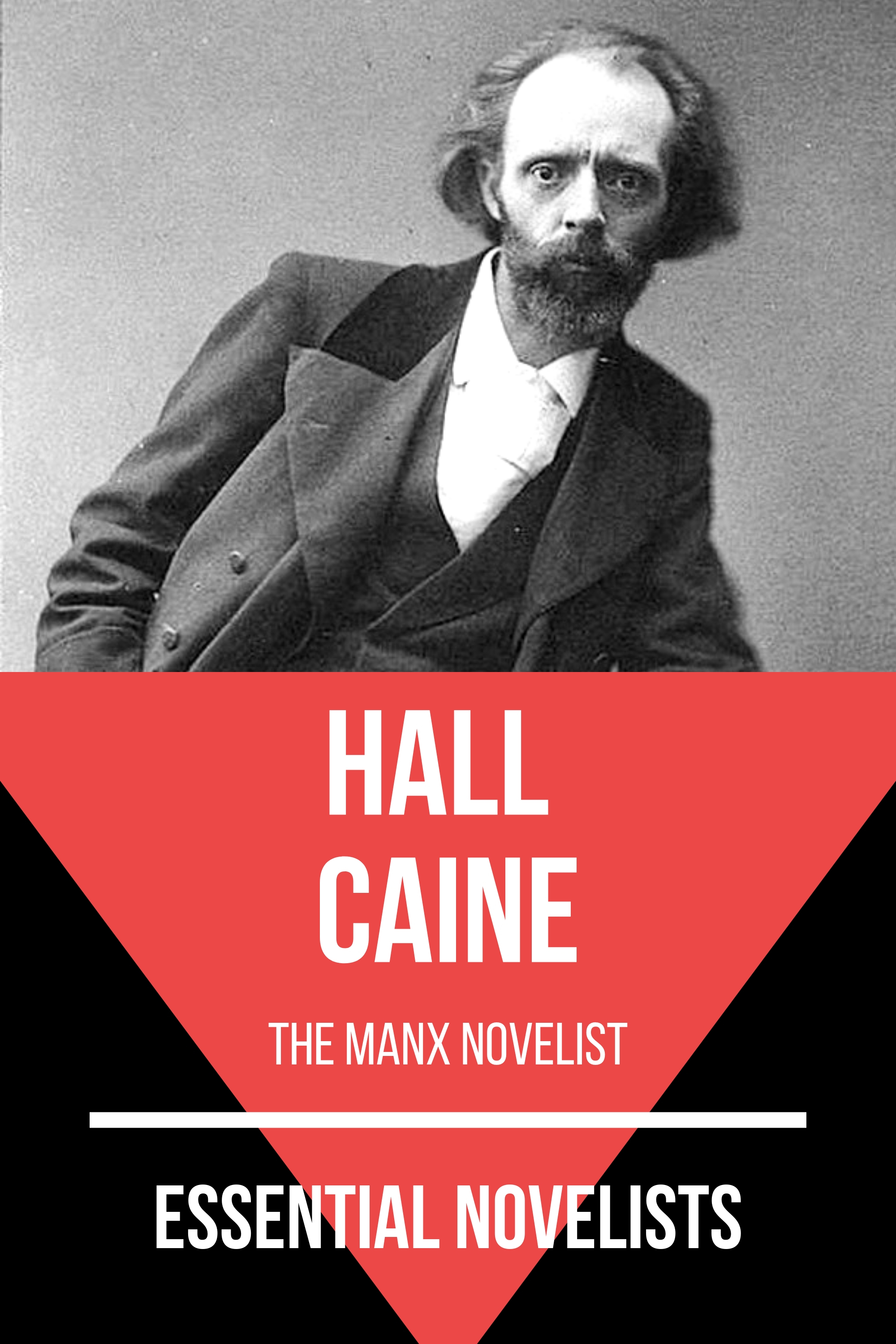

SIR THOMAS HENRY HALL Caine CH KBE (14 May 1853 – 31 August 1931), usually known as Hall Caine, was a British novelist, dramatist, short story writer, poet and critic of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Caine's popularity during his lifetime was unprecedented. He wrote fifteen novels on subjects of adultery, divorce, domestic violence, illegitimacy, infanticide, religious bigotry and women's rights, became an international literary celebrity, and sold a total of ten million books. Caine was the most highly paid novelist of his day. The Eternal City is the first novel to have sold over a million copies worldwide. In addition to his books, Caine is the author of more than a dozen plays and was one of the most commercially successful dramatists of his time; many were West End and Broadway productions. Caine adapted seven of his novels for the stage. He collaborated with leading actors and managers, including Wilson Barrett, Viola Allen, Herbert Beerbohm Tree, Louis Napoleon Parker, Mrs Patrick Campbell, George Alexander, and Arthur Collins. Most of Caine's novels were adapted into silent black and white films. A. E. Coleby's 1923 18,454 feet, nineteen-reel film The Prodigal Son became the longest commercially made British film. Alfred Hitchcock's 1929 film The Manxman, is Hitchcock's last silent film.

Born in Runcorn to a Manx father and Cumbrian mother, Caine was raised in Liverpool. After spending four years in school, Caine was trained as an architectural draughtsman. While growing up he spent childhood holidays with relatives in the Isle of Man. At seventeen he spent a year there as schoolmaster in Maughold. Afterwards he returned to Liverpool and began a career in journalism, becoming a leader-writer on the Liverpool Mercury. As a lecturer and theatre critic he developed a circle of eminent literary friends by whom he was influenced. Caine moved to London at Dante Gabriel Rossetti's suggestion and lived with the poet, acting as secretary and companion during the last years of Rossetti's life. Following the publication of his Recollections of Rossetti in 1882, Caine began his career as a writer spanning four decades.

Caine established his residency in the Isle of Man in 1895, where he sat from 1901 to 1908 in the Manx House of Keys, the lower house of its legislature. Caine was elected President of the Manx National Reform League in 1903 and chair of the Keys' Committee that prepared the 1907 petition for constitutional reform. In 1929 Caine was granted the Freedom of the Borough of Douglas, Isle of Man. Caine visited Russia in 1892 on behalf of the persecuted Jews. In 1895 Caine travelled in the United States and Canada, where he represented the Society of Authors conducting successful negotiations and obtaining important international copyright concessions from the Dominion Parliament.

During the Great War (1914–1918) Caine wrote many patriotic articles and edited King Albert's Book, the proceeds of which went to help Belgian refugees. In 1917, Caine was created an Officer of the Order of Leopold by King Albert I of Belgium. Caine cancelled many literary contracts in America to devote all his time and energy to the British war effort. On the recommendation of the Prime Minister Lloyd George for services as an Allied propagandist in the United States, King George V made him a Knight of the British Empire in 1918 and a Companion of Honour in 1922. Aged 78 Caine died in his home at Greeba Castle on the Isle of Man.

The Manxman

PART I. BOYS TOGETHER.

I.

––––––––

OLD DEEMSTER CHRISTIAN of Ballawhaine was a hard man—hard on the outside, at all events. They called him Iron Christian, and people said, “Don't turn that iron hand against you.” Yet his character was stamped with nobleness as well as strength. He was not a man of icy nature, but he loved to gather icicles about him. There was fire enough underneath, at which he warmed his old heart when alone, but he liked the air to be congealed about his face. He was a man of a closed soul. One had to wrench open the dark chamber where he kept his feelings; but the man who had done that had uncovered his nakedness, and he cut him off for ever. That was how it happened with his son, the father of Philip.

He had two sons; the elder was an impetuous creature, a fiery spirit, one of the masterful souls who want the restraint of the curb if they are not to hurry headlong into the abyss. Old Deemster Christian had called this boy Thomas Wilson, after the serene saint who had once been Bishop of Man. He was intended, however, for the law, not for the Church. The office of Deemster never has been and never can be hereditary; yet the Christians of Ballawhaine had been Deemsters through six generations, and old Iron Christian expected that Thomas Wilson Christian would succeed him. But there was enough uncertainty about the succession to make merit of more value than precedent in the selection, and so the old man had brought up his son to the English bar, and afterwards called him to practise in the Manx one. The young fellow had not altogether rewarded his father's endeavours. During his residence in England, he had acquired certain modern doctrines which were highly obnoxious to the old Deemster. New views on property, new ideas about woman and marriage, new theories concerning religion (always re-christened superstition), the usual barnacles of young vessels fresh from unknown waters; but the old man was no shipwright in harbour who has learnt the art of removing them without injury to the hull. The Deemster knew these notions when he met with them in the English newspapers. There was something awesome in their effect on his stay-at-home imagination, as of vices confusing and difficult to true men that walk steadily; but, above all, very far off, over the mountains and across the sea, like distant cities of Sodom, only waiting for Sodom's doom. And yet, lo! here they were in a twinkling, shunted and shot into his own house and his own stackyard.

“I suppose now,” he said, with a knowing look, “you think Jack as good as his master?”

“No, sir,” said his son gravely; “generally much better.”

Iron Christian altered his will. To his elder son he left only a life-interest in Ballawhaine. “That boy will be doing something,” he said, and thus he guarded against consequences. He could not help it; he was ashamed, but he could not conquer his shame—the fiery old man began to nurse a grievance against his son.

The two sons of the Deemster were like the inside and outside of a bowl, and that bowl was the Deemster himself. If Thomas Wilson the elder had his father's inside fire and softness, Peter, the younger, had his father's outside ice and iron. Peter was little and almost misshapen, with a pair of shoulders that seemed to be trying to meet over a hollow chest and limbs that splayed away into vacancy. And if Nature had been grudging with him, his father was not more kind. He had been brought up to no profession, and his expectations were limited to a yearly charge out of his brother's property. His talk was bitter, his voice cold, he laughed little, and had never been known to cry. He had many things against him.

Besides these sons, Deemster Christian had a girl in his household, but to his own consciousness the fact was only a kind of peradventure. She was his niece, the child of his only brother, who had died in early manhood. Her name was Ann Charlotte de la Tremouille, called after the lady of Rushen, for the family of Christian had their share of the heroic that is in all men. She had fine eyes, a weak mouth, and great timidity. Gentle airs floated always about her, and a sort of nervous brightness twinkled over her, as of a glen with the sun flickering through. Her mother died when she was a child of twelve, and in the house of her uncle and her cousins she had been brought up among men and boys.

One day Peter drew the Deemster aside and told him (with expressions of shame, interlarded with praises of his own acuteness) a story of his brother. It was about a girl. Her name was Mona Crellin; she lived on the hill at Ballure House, half a mile south of Ramsey, and was daughter of a man called Billy Ballure, a retired sea-captain, and hail-fellow-well-met with all the jovial spirits of the town.

There was much noise and outcry, and old Iron sent for his son.

“What's this I hear?” he cried, looking him down. “A woman? So that's what your fine learning comes to, eh? Take care, sir! take care! No son of mine shall disgrace himself. The day he does that he will be put to the door.”

Thomas held himself in with a great effort.

“Disgrace?” he said. “What disgrace, sir, if you please?”

“What disgrace, sir?” repeated the Deemster, mocking his son in a mincing treble. Then he roared, “Behaving dishonourably to a poor girl—that what's disgrace, sir! Isn't it enough? eh? eh?”

“More than enough,” said the young man. “But who is doing it? I'm not.”

“Then you're doing worse. Did I say worse? Of course I said worse. Worse, sir, worse! Do you hear me? Worse! You are trapsing around Ballure, and letting that poor girl take notions. I'll have no more of it. Is this what I sent you to England for? Aren't you ashamed of yourself? Keep your place, sir; keep your place. A poor girl's a poor girl, and a Deemster's a Deemster.”

“Yes, sir,” said Thomas, suddenly firing up, “and a man's a man. As for the shame, I need be ashamed of nothing that is not shameful; and the best proof I can give you that I mean no dishonour by the girl is that I intend to marry her.”

“What? You intend to—what? Did I hear——”

The old Deemster turned his good ear towards his son's face, and the young man repeated his threat. Never fear! No poor girl should be misled by him. He was above all foolish conventions.

Old Iron Christian was dumbfounded. He gasped, he stared, he stammered, and then fell on his son with hot reproaches.

“What? Your wife? Wife? That trollop!—that minx! that—and daughter of that sot, too, that old rip, that rowdy blatherskite—that——And my own son is to lift his hand to cut his throat! Yes, sir, cut his throat——And I am to stand by! No, no! I say no, sir, no!”

The young man made some further protest, but it was lost in his father's clamour.

“You will, though? You will? Then your hat is your house, sir. Take to it—take to it!”

“No need to tell me twice, father.”

“Away then—away to your woman—your jade! God, keep my hands off him!”

The old man lifted his clenched fist, but his son had flung out of the room. It was not the Deemster only who feared he might lay hands on his own flesh and blood.

“Stop! come back, you dog! Listen! I've not done yet. Stop! you hotheaded rascal, stop! Can't you hear a man out then? Come back! Thomas Wilson, come back, sir! Thomas! Thomas! Tom! Where is he? Where's the boy?”

Old Iron Christian had made after his son bareheaded down to the road, shouting his name in a broken roar, but the young man was gone. Then he went back slowly, his grey hair playing in the wind. He was all iron outside, but all father within.

That day the Deemster altered his will a second time, and his elder son was disinherited.

II.

––––––––

PETER SUCCEEDED IN due course to the estate of Ballawhaine, but he was not a lawyer, and the line of the Deemsters Christian was broken.

Meantime Thomas Wilson Christian had been married to Mona Crellin without delay. He loved her, but he had been afraid of her ignorance, afraid also (notwithstanding his principles) of the difference in their social rank, and had half intended to give her up when his father's reproaches had come to fire his anger and to spur his courage. As soon as she became his wife he realised the price he had paid for her. Happiness could not come of such a beginning. He had broken every tie in making the one which brought him down. The rich disowned him, and the poor lost respect for him.

“It's positively indecent,” said one. “It's potatoes marrying herrings,” said another. It was little better than hunger marrying thirst.

In the general downfall of his fame his profession failed him. He lost heart and ambition. His philosophy did not stand him in good stead, for it had no value in the market to which he brought it. Thus, day by day, he sank deeper into the ooze of a wrecked and wasted life.

The wife did not turn out well. She was a fretful person, with a good face, a bad shape, a vacant mind, and a great deal of vanity. She had liked her husband a little as a lover, but when she saw that her marriage brought her nobody's envy, she fell into a long fit of the vapours. Eventually she made herself believe that she was an ill-used person. She never ceased to complain of her fate. Everybody treated her as if she had laid plans for her husband's ruin.

The husband continued to love her, but little by little he grew to despise her also. When he made his first plunge, he had prided himself on indulging an heroic impulse. He was not going to deliver a good woman to dishonour because she seemed to be an obstacle to his success. But she had never realised his sacrifice. She did not appear to understand that he might have been a great man in the island, but that love and honour had held him back. Her ignorance was pitiful, and he was ashamed of it. In earning the contempt of others he had not saved himself from self-contempt.

The old sailor died suddenly in a fit of drunkenness at a fair, and husband and wife came into possession of his house and property at Ballure. This did not improve the relations between them. The woman perceived that their positions were reversed. She was the bread-bringer now. One day, at a slight that her husband's people had put upon her in the street, she reminded him, in order to re-establish her wounded vanity, that but for her and hers he would not have so much as a roof to cover him.

Yet the man continued to love her in spite of all. And she was not at first a degraded being. At times she was bright and cheerful, and, except in the worst spells of her vapours, she was a brisk and busy woman. The house was sweet and homely. There was only one thing to drive him away from it, but that was the greatest thing of all. Nevertheless they had their cheerful hours together.

A child was born, a boy, and they called him Philip. He was the beginning of the end between them; the iron stay that held them together and yet apart. The father remembered his misfortunes in the presence of his son, and the mother was stung afresh by the recollection of disappointed hopes. The boy was the true heir of Ballawhaine, but the inheritance was lost to him by his father's fault and he had nothing.

Philip grew to be a winsome lad. There was something sweet and amiable and big-hearted, and even almost great, in him. One day the father sat in the garden by the mighty fuchsia-tree that grows on the lawn, watching his little fair-haired son play at marbles on the path with two big lads whom he had enticed out of the road, and another more familiar playmate—the little barefooted boy Peter, from the cottage by the water-trough. At first Philip lost, and with grunts of satisfaction the big ones promptly pocketed their gains. Then Philip won, and little curly Peter was stripped naked, and his lip began to fall. At that Philip paused, held his head aside, and considered, and then said quite briskly, “Peter hadn't a fair chance that time—here, let's give him another go.”

The father's throat swelled, and he went indoors to the mother and said, “I think—perhaps I'm to blame—but somehow I think our boy isn't like other boys. What do you say? Foolish? May be so, may be so! No difference? Well, no—no!”

But deep down in the secret place of his heart, Thomas Wilson Christian, broken man, uprooted tree, wrecked craft in the mud and slime, began to cherish a fond idea. The son would regain all that his father had lost! He had gifts, and he should be brought up to the law; a large nature, and he should be helped to develop it; a fine face which all must love, a sense of justice, and a great wealth of the power of radiating happiness. Deemster? Why not? Ballawhaine? Who could tell? The biggest, noblest, greatest of all Manxmen! God knows!

Only—only he must be taught to fly from his father's dangers. Love? Then let him love where he can also respect—but never outside his own sphere. The island was too little for that. To love and to despise was to suffer the torments of the damned.

Nourishing these dreams, the poor man began to be tortured by every caress the mother gave her son, and irritated by every word she spoke to him. Her grammar was good enough for himself, and the exuberant caresses of her maudlin moods were even sometimes pleasant, but the boy must be degraded by neither.

The woman did not reach to these high thoughts, but she was not slow to interpret the casual byplay in which they found expression. Her husband was taiching her son to dis-respeck her. She wouldn't have thought it of him—she wouldn't really. But it was always the way when a plain practical woman married on the quality. Imperence and dis-respeck—that's the capers! Imperence and disrespeck from the ones that's doing nothing and behoulden to you for everything. It was shocking! It was disthressing!

In such outbursts would her jealousy taunt him with his poverty, revile him for his idleness, and square accounts with him for the manifest preference of the boy. He could bear them with patience when they were alone, but in Philip's presence they were as gall and wormwood, and whips and scorpions.

“Go, my lad, go,” he would sometimes whimper, and hustle the boy out of the way.

“No,” the woman would cry, “stop and see the man your father is.”

And the father would mutter, “He might see the woman his mother is as well.”

But when she had pinned them together, and the boy had to hear her out, the man would drop his forehead on the table and break into groans and tears. Then the woman would change quite suddenly, and put her arms about him and kiss him and weep over him. He could defend himself from neither her insults nor her embraces. In spite of everything he loved her. That was where the bitterness of the evil lay. But for the love he bore her, he might have got her off his back and been his own man once more. He would make peace with her and kiss her again, and they would both kiss the boy, and be tender, and even cheerful.

Philip was still a child, but he saw the relations of his parents, and in his own way he understood everything. He loved his father best, but he did not hate his mother. She was nearly always affectionate, though often jealous of the father's greater love and care for him, and sometimes irritable from that cause alone. But the frequent broils between them were like blows that left scars on his body. He slept in a cot in the same room, and he would cover up his head in the bedclothes at night with a feeling of fear and physical pain.

A man cannot fight against himself for long. That deadly enemy is certain to slay. When Philip was six years old his father lay sick of his last sickness. The wife had fallen into habits of intemperance by this time, and stage by stage she had descended to the condition of an utterly degraded woman. There was something to excuse her. She had been disappointed in the great stakes of life; she had earned disgrace where she had looked for admiration. She was vain, and could not bear misfortune; and she had no deep well of love from which to drink when the fount of her pride ran dry. If her husband had indulged her with a little pity, everything might have gone along more easily. But he had only loved her and been ashamed. And now that he lay near to his death, the love began to ebb and the shame to deepen into dread.

He slept little at night, and as often as he closed his eyes certain voices of mocking and reproach seemed to be constantly humming in his ears.

“Your son!” they would cry. “What is to become of him? Your dreams! Your great dreams! Deemster! Ballawhaine! God knows what! You are leaving the boy; who is to bring him up? His mother? Think of it!”

At last a ray of pale sunshine broke on the sleepless wrestler with the night, and he became almost happy. “I'll speak to the boy,” he thought. “I will tell him my own history, concealing nothing. Yes, I will tell him of my own father also, God rest him, the stern old man—severe, yet just.”

An opportunity soon befell. It was late at night—very late. The woman was sleeping off a bout of intemperance somewhere below; and the boy, with the innocence and ignorance of his years in all that the solemn time foreboded, was bustling about the room with mighty eagerness, because he knew that he ought to be in bed.

“I'm staying up to intend on you, father,” said the boy.

The father answered with a sigh.

“Don't you asturb yourself, father. I'll intend on you.”

The father's sigh deepened to a moan.

“If you want anything 'aticular, just call me; d'ye see, father?”

And away went the boy like a gleam of light. Presently he came back, leaping like the dawn. He was carrying, insecurely, a jug of poppy-head and camomile, which had been prescribed as a lotion.

“Poppy heads, father! Poppy-heads is good, I can tell ye.”

“Why arn't you in bed, child?” said the father. “You must be tired.”

“No, I'm not tired, father. I was just feeling a bit of tired, and then I took a smell of poppy-heads and away went the tiredness to Jericho. They is good.”

The little white head was glinting off again when the father called it back.

“Come here, my boy.” The child went up to the bedside, and the father ran his fingers lovingly through the long fair hair.

“Do you think, Philip, that twenty, thirty, forty years hence, when you are a man—aye, a big man, little one—do you think you will remember what I shall say to you now?”

“Why, yes, father, if it's anything 'aticular, and if it isn't you can amind me of it, can't you, father?”

The father shook his head. “I shall not be here then, my boy. I am going away——”

“Going away, father? May I come too?”

“Ah! I wish you could, little one. Yes, truly I almost wish you could.”

“Then you'll let me go with you, father! Oh, I am glad, father.” And the boy began to caper and dance, to go down on all fours, and leap about the floor like a frog.

The father fell back on his pillow with a heaving breast. Vain! vain! What was the use of speaking? The child's outlook was life; his own was death; they had no common ground; they spoke different tongues. And, after all, how could he suffer the sweet innocence of the child's soul to look down into the stained and scarred chamber of his ruined heart?

“You don't understand me, Philip. I mean that I am going—to die. Yes, darling, and, only that I am leaving you behind, I should be glad to go. My life has been wasted, Philip. In the time to come, when men speak of your father, you will be ashamed. Perhaps you will not remember then that whatever he was he was a good father to you, for at least he loved you dearly. Well, I must needs bow to the will of God, but if I could only hope that you would live to restore my name when I am gone.... Philip, are you—don't cry, my darling. There, there, kiss me. We'll say no more about it then. Perhaps it's not true, although father tolded you? Well, perhaps not. And now undress and slip into bed before mother comes. See, there's your night-dress at the foot of the crib. Wants some buttons, does it? Never mind—in with you—that's a boy.”

Impossible, impossible! And perhaps unnecessary. Who should say? Young as the child was, he might never forget what he had seen and heard. Some day it must have its meaning for him. Thus the father comforted himself. Those jangling quarrels which had often scorched his brain like iron—the memory of their abject scenes came to him then, with a sort of bleeding solace!

Meanwhile, with little catching sobs, which he struggled to repress, the boy lay down in his crib. When half-way gone towards the mists of the land of sleep, he started up suddenly, and called “Good night, father,” and his father answered him “Good night.”

Towards three o'clock the next morning there was great commotion in the house. The servant was scurrying up and downstairs, and the mistress, wringing her hands, was tramping to and fro in the sick-room, crying in a tone of astonishment, as if the thought had stolen upon her unawares, “Why, he's going! How didn't somebody tell me before?”

The eyes of the sinking man were on the crib. “Philip,” he faltered. They lifted the boy out of his bed, and brought him in his night-dress to his father's side; and the father twisted about and took him into his arms, still half asleep and yawning. Then the mother, recovering from the stupidity of her surprise, broke into paroxysms of weeping, and fell over her husband's breast and kissed and kissed him.

For once her kisses had no response. The man was dying miserably, for he was thinking of her and of the boy. Sometimes he babbled over Philip in a soft, inarticulate gurgle; sometimes he looked up at his wife's face with a stony stare, and then he clung the closer to the boy, as if he would never let him go. The dark hour came, and still he held the boy in his arms. They had to release the child at last from his father's dying grip.

The dead of the night was gone by this time, and the day was at the point of dawn; the sparrows in the eaves were twittering, and the tide, which was at its lowest ebb, was heaving on the sand far out in the bay with the sound as of a rookery awakening. Philip remembered afterwards that his mother cried so much that he was afraid, and that when he had been dressed she took him downstairs, where they all ate breakfast together, with the sun shining through the blinds.

The mother did not live to overshadow her son's life. Sinking yet lower in habits of intemperance, she stayed indoors from week-end to week-end, seated herself like a weeping willow by the fireside, and drank and drank. Her excesses led to delusions. She saw ghosts perpetually. To avoid such of them as haunted the death-room of her husband, she had a bed made up on a couch in the parlour, and one morning she was found face downwards stretched out beside it on the floor.

Then Philip's father's cousin, always called his Aunty Nan, came to Ballure House to bring him up. His father had been her favourite cousin, and, in spite of all that had happened, he had been her lifelong hero also. A deep and secret tenderness, too timid to be quite aware of itself, had been lying in ambush in her heart through all the years of his miserable life with Mona. At the death of the old Deemster, her other cousin, Peter, had married and cast her off. But she was always one of those woodland herbs which are said to give out their sweetest fragrance after they have been trodden on and crushed. Philip's father had been her hero, her lost one and her love, and Philip was his father's son.

III.

––––––––

LITTLE CURLY PETE, with the broad, bare feet, the tousled black head, the jacket half way up his back like a waistcoat with sleeves, and the hole in his trousers where the tail of his shirt should have been, was Peter Quilliam, and he was the natural son of Peter Christian. In the days when that punctilious worthy set himself to observe the doings of his elder brother at Ballure, he found it convenient to make an outwork of the hedge in front of the thatched house that stood nearest. Two persons lived in the cottage, father and daughter—Tom Quilliam, usually called Black Tom, and Bridget Quilliam, getting the name of Bridget Black Tom.

The man was a short, gross creature, with an enormous head and a big, open mouth, showing broken teeth that were black with the juice of tobacco. The girl was by common judgment and report a gawk—a great, slow-eyed, comely-looking, comfortable, easy-going gawk. Black Tom was a thatcher, and with his hair poking its way through the holes in his straw hat, he tramped the island in pursuit of his calling. This kept him from home for days together, and in that fact Peter Christian, while shadowing the morality of his brother, found his own opportunity.

When the child was born, neither the thatcher nor his daughter attempted to father it. Peter Christian paid twenty pounds to the one and eighty to the other in Manx pound-notes, the boys daubed their door to show that the house was dishonoured, and that was the end of everything.

The girl went through her “censures” silently, or with only one comment. She had borrowed the sheet in which she appeared in church from Miss Christian of Ballawhaine, and when she took it back, the good soul of the sweet lady thought to improve the occasion.

“I was wondering, Bridget,” she said gravely, “what you were thinking of when you stood with Bella and Liza before the congregation last Sunday morning”—two other Magda-lenes had done penance by Bridget's side.

“'Deed, mistress,” said the girl, “I was thinkin' there wasn't a sheet at one of them to match mine for whiteness. I'd 'a been ashamed to be seen in the like of theirs.”

Bridget may have been a gawk, but she did two things which were not gawkish. Putting the eighty greasy notes into the foot of an old stocking, she sewed them up in the ticking of her bed, and then christened her baby Peter. The money was for the child if she should not live to rear him, and the name was her way of saying that a man's son was his son in spite of law or devil.

After that she kept both herself and her child by day labour in the fields, weeding and sowing potatoes, and following at the tail of the reapers, for sixpence a day dry days, and fourpence all weathers. She might have badgered the heir of Ballawhaine, but she never did so. That person came into his inheritance, got himself elected member for Ramsey in the House of Keys, married Nessy Taubman, daughter of the rich brewer, and became the father of another son. Such were the doings in the big house down in the valley, while up in the thatched cottage behind the water-trough, on potatoes and herrings and barley bonnag, lived Bridget and her little Pete.

Pete's earliest recollections were of a boy who lived at the beautiful white house with the big fuchsia, by the turn of the road over the bridge that crossed the glen. This was Philip Christian, half a year older than himself, although several inches shorter, with long yellow hair and rosy cheeks, and dressed in a velvet suit of knickerbockers. Pete worshipped him in his simple way, hung about him, fetched and carried for him, and looked up to him as a marvel of wisdom and goodness and pluck.

His first memory of Philip was of sleeping with him, snuggled up by his side in the dark, hushed and still in a narrow bed with iron ends to it, and of leaping up in the morning and laughing. Philip's father—a tall, white gentleman, who never laughed at all, and only smiled sometimes—had found him in the road in the evening waiting for his mother to come home from the fields, that he might light the fire in the cottage, and running about in the meantime to keep himself warm, and not too hungry.

His second memory was of Philip guiding him round the drawing-room (over thick carpets, on which his bare feet made no noise), and showing him the pictures on the walls, and telling him what they meant. One (an engraving of St. John, with a death's-head and a crucifix) was, according to this grim and veracious guide, a picture of a brigand who killed his victims, and always skinned their skulls with a cross-handled dagger. After that his memories of Philip and himself were as two gleams of sunshine which mingle and become one.

Philip was a great reader of noble histories. He found them, frayed and tattered, at the bottom of a trunk that had tin corners and two padlocks, and stood in the room looking towards the harbour where his mother's father, the old sailor, had slept. One of them was his special favourite, and he used to read it aloud to Pete. It told of the doings of the Carrasdhoo men. They were a bold band of desperadoes, the terror of all the island. Sometimes they worked in the fields at ploughing, and reaping, and stacking, the same as common practical men; and sometimes they lived in houses, just like the house by the water-trough. But when the wind was rising in the nor-nor-west, and there was a taste of the brine on your lips, they would be up, and say, “The sea's calling us—we must be going.” Then they would live in rocky caves of the coast where nobody could reach them, and there would be fires lit at night in tar-barrels, and shouting, and singing, and carousing; and after that there would be ships' rudders, and figure heads, and masts coming up with the tide, and sometimes dead bodies on the beach of sailors they had drowned—only foreign ones though—hundreds and tons of them. But that was long ago, the Carrasdhoo men were dead, and the glory of their day was departed.

One quiet evening, after an awesome reading of this brave history, Philip, sitting on his haunches at the gable, with Pete like another white frog beside him, said quite suddenly, “Hush! What's that?”

“I wonder,” said Pete.

There was never a sound in the air above the rustle of a leaf, and Pete's imagination could carry him no further.

“Pete,” said Philip, with awful gravity, “the sea's calling me.”

“And me,” said Pete solemnly.

Early that night the two lads were down at the most desolate part of Port Mooar, in a cave under the scraggy black rocks of Gobny-Garvain, kindling a fire of gorse and turf inside the remains of a broken barrel.

“See that tremendous sharp rock below low water?” said Philip.

“Don't I, though?” said Pete.

There was never a rock the size of a currycomb between them and the line of the sky.

“That's what we call a reef,” said Philip. “Wait a bit and you'll see the ships go splitting on top of it like—like——”

“Like a tay-pot,” said Pete.

“We'll save the women, though,” said Philip. “Shall we save the women, Pete? We always do.”

“Aw, yes, the women—and the boys,” said Pete thoughtfully.

Philip had his doubts about the boys, but he would not quarrel. It was nearly dark, and growing very cold. The lads croodled down by the crackling blaze, and tried to forget that they had forgotten tea-time.

“We never has to mind a bit of hungry,” said Philip stoutly.

“Never a ha'p'orth,” said Pete.

“Only when the job's done we have hams and flitches and things for supper.”

“Aw, yes, ateing and drinking to the full.”

“Rum, Pete, we always drinks rum.”

“We has to,” said Pete.

“None of your tea,” said Philip.

“Coorse not, none of your ould grannie's two-penny tay,” said Pete.

It was quite dark by this time, and the tide was rising rapidly. There was not a star in the sky, and not a light on the sea except the revolving light of the lightship far a Way. The boys crept closer together and began to think of home. Philip remembered Aunty Nan. When he had stolen away on hands and knees under the parlour window she had been sewing at his new check night-shirt. A night-shirt for a Carrasdhoo man had seemed to be ridiculous then; but where was Aunty Nannie now? Pete remembered his mother—she would be racing round the houses and crying; and he had visions of Black Tom—he would be racing round also and swearing.

“Shouldn't we sing something, Phil?” said Pete, with a gurgle in his throat.

“Sing!” said Philip, with as much scorn as he could summon, “and give them warning we're watching for them! Well, you are a pretty, Mr. Pete! But just you wait till the ships goes wrecking on the rocks—I mean the reefs—and the dead men's coming up like corks—hundreds and ninety and dozens of them; my jove! yes, then you'll hear me singing.”

The darkness deepened, and the voice of the sea began to moan through the back of the cave, the gorse crackled no longer, and the turf burned in a dull red glow. Night with its awfulness had come down, and the boys were cut off from everything.

“They don't seem to be coming—not yet,” said Philip, in a husky whisper.

“Maybe it's the same as fishing,” said Pete; “sometimes you catch and sometimes you don't.”

“That's it,” said Philip eagerly, “generally you don't—and then you both haves to go home and come again,” he added nervously.

But neither of the boys stirred. Outside the glow of the fire the blackness looked terrible. Pete nuzzled up to Philip's side, and, being untroubled by imaginative fears, soon began to feel drowsy. The sound of his measured breathing startled Philip with the terror of loneliness.

“Honour bright, Mr. Pete,” he faltered, nudging the head on his shoulder, and trying to keep his voice from shaking; “you call yourself a second mate, and leaving all the work to me!”

The second mate was penitent, but in less than half a minute more he was committing the same offence again. “It isn't no use,” he said, “I'm that sleepy you never seen.”

“Then let's both take the watch below i'stead,” said Philip, and they proceeded to stretch themselves out by the fire together.

“Just lave it to me,” said Pete; “I'll hear them if they come in the night. I'll always does. I'm sleeping that light it's shocking. Why, sometimes I hear Black Tom when he comes home tipsy. I've done it times.”

“We'll have carpets to lie on to-morrow, not stones,” said Philip, wriggling on a rough one; “rolls of carpets—kidaminstrel ones.”

They settled themselves side by side as close to each other as they could creep, and tried not to hear the surging and sighing of the sea. Then came a tremulous whimper:

“Pete!”

“What's that?”

“Don't you never say your prayers when you take the watch below?”

“Sometimes we does, when mother isn't too tired, and the ould man's middling drunk and quiet.”

“Then don't you like to then?”

“Aw, yes, though, I'm liking it scandalous.”

The wreckers agreed to say their prayers, and got up again and said them, knee to knee, with their two little faces to the fire, and then stretched themselves out afresh.

“Pete, where's your hand?”

“Here you are, Phil.”

In another minute, under the solemn darkness of the night, broken only by the smouldering fire, amid the thunderous quake of the cavern after every beat of the waves on the beach, the Carrasdhoo men were asleep.

Sometime in the dark reaches before the dawn Pete leapt up with a start “What's that?” he cried, in a voice of fear.

But Philip was still in the mists of sleep, and, feeling the cold, he only whimpered, “Cover me up, Pete.”

“Phil!” cried Pete, in an affrighted whisper.

“Cover me up,” drawled Philip.

“I thought it was Black Tom,” said Pete.

There was some confused bellowing outside the cave.

“My goodness grayshers!” came in a terrible voice, “it's them, though, the pair of them! Impozzible! who says it's impozzible? It's themselves I'm telling you, ma'm. Guy heng! The woman's mad, putting a scream out of herself like yonder. Safe? Coorse they're safe, bad luck to the young wastrels! You're for putting up a prayer for your own one. Eh? Well, I'm for hommering mine. The dirts? Weaned only yesterday, and fetching a dacent man out of his bed to find them. A fire at them, too! Well, it was the fire that found them. Pull the boat up, boys.”

Philip was half awake by this time. “They've come,” he whispered. “The ships is come, they're on the reef. Oh, dear me! Best go and meet them. P'raps they won't kill us if—if we—Oh, dear me!”

Then the wreckers, hand in hand, quaking and whimpering, stepped out to the mouth of the cave. At the next moment Philip found himself snatched up into the arms of Aunty Nan, who kissed him and cried over him, and rammed a great chunk of sweet cake into his cheek. Pete was faring differently. Under the leathern belt of Black Tom, who was thrashing him for both of them, he was howling like the sea in a storm.

Thus the Carrasdhoo men came home by the light of early morning—Pete skipping before the belt and bellowing; and Philip holding a piece of the cake at his teeth to comfort him.

IV.

––––––––

PHILIP LEFT HOME FOR school at King William's by Castletown, and then Pete had a hard upbringing. His mother was tender enough, and there were good souls like Aunty Nan to show pity to both of them. But life went like a springless bogey, nevertheless. Sin itself is often easier than simpleness to pardon and condone. It takes a soft heart to feel tenderly towards a soft head.

Poor Pete's head seemed soft enough and to spare. No power and no persuasion could teach him to read and write. He went to school at the old schoolhouse by the church in Maughold village. The schoolmaster was a little man called John Thomas Corlett, pert and proud, with the sharp nose of a pike and the gait of a bantam. John Thomas was also a tailor. On a cowhouse door laid across two school forms he sat cross-legged among his cloth, his “maidens,” and his smoothing irons, with his boys and girls, class by class, in a big half circle round about him.

The great little man had one standing ground of daily assault on the dusty jacket of poor Pete, and that was that the lad came late to school. Every morning Pete's welcome from the tailor-schoolmaster was a volley of expletives, and a swipe of the cane across his shoulders. “The craythur! The dunce! The durt! I'm taiching him, and taiching him, and he won't be taicht.”

The soul of the schoolmaster had just two human weaknesses. One of these was a weakness for drink, and as a little vessel he could not take much without being full. Then he always taught the Church catechism and swore at his boys in Manx.

“Peter Quilliam,” he cried one day, “who brought you out of the land of Egypt and the house of bondage?”

“'Deed, master,” said Pete, “I never was in no such places, for I never had the money nor the clothes for it, and that's how stories are getting about.”

The second of the schoolmaster's frailties was love of his daughter, a child of four, a cripple, whom he had lamed in her infancy, by letting her fall as he tossed her in his arms while in drink. The constant terror of his mind was lest some further accident should befall her. Between class and class he would go to a window, from which, when he had thrown up its lower sash, dim with the scratches of names, he could see one end of his own white cottage, and the little pathway, between lines of gilvers, coming down from the porch.

Pete had seen the little one hobbling along this path on her lame leg, and giggling with a heart of glee when she had eluded the eyes of her mother and escaped into the road. One day it chanced, after the heavy spring rains had swollen every watercourse, that he came upon the little curly poll, tumbling and tossing like a bell-buoy in a gale, down the flood of the river that runs to the sea at Port Mooar. Pete rescued the child and took her home, and then, as if he had done nothing unusual, he went on to school, dripping water from his legs at every step.

When John Thomas saw him coming, in bare feet, triddle-traddle, triddle-traddle, up the school-house floor, his indignation at the boy for being later than usual rose to fiery wrath for being drenched as well. Waiting for no explanation, concluding that Pete had been fishing for crabs among the stones of Port Lewaigue, he burst into a loud volley of his accustomed expletives, and timed and punctuated them by a thwack of the cane between every word.

“The waistrel! (thwack). The dirt! (thwack). I'm taiching him (thwack), and taiching him (thwack), and he won't be taicht!” (Thwack, thwack, thwack.)

Pete said never a word. Boiling his stinging shoulders under his jacket, and ramming his smarting hands, like wet eels, into his breeches' pockets, he took his place in silence at the bottom of the class.

But a girl, a little dark thing in a red frock, stepped out from her place beside the boy, shot up like a gleam to the schoolmaster as he returned to his seat among the cloth and needles, dealt him a smart slap across the face, and then burst into a lit of hysterical crying. Her name was Katherine Cregeen. She was the daughter of Cæsar the Cornaa miller, the founder of Ballajora Chapel, and a mighty man among the Methodists.

Katherine went unpunished, but that was the end of Pete's schooling. His learning was not too heavy for a big lad's head to carry—a bit of reading if it was all in print, and no writing at all except half-a-dozen capital letters. It was not a formidable equipment for the battle of life, but Bridget would not hear of more.

She herself, meanwhile, had annexed that character which was always the first and easiest to attach itself to a woman with a child but no visible father for it—the character of a witch. That name for his mother was Pete's earliest recollection of the high-road, and when the consciousness of its meaning came to him, he did not rebel, but sullenly acquiesced, for he had been born to it and knew nothing to the contrary. If the boys quarrelled with him at play, the first word was “your mother's a butch.” Then he cried at the reproach, or perhaps fought like a vengeance at the insult, but he never dreamt of disbelieving the fact or of loving his mother any the less.

Bridget was accused of the evil eye. Cattle sickened in the fields, and when there was no proof that she had looked over the gate, the idea was suggested that she crossed them as a hare. One day a neighbour's dog started a hare in a meadow where some cows were grazing. This was observed by a gang of boys playing at hockey in the road. Instantly there was a shout and a whoop, and the boys with their sticks were in full chase after the yelping dog, crying, “The butch! The butch! It's Bridget Tom! Corlett's dogs are hunting Bridget Black Tom! Kill her, Laddie! Kill her, Sailor! Jump, dog, jump!”

One of the boys playing at hockey was Pete. When his play-fellows ran after the dogs in their fanatic thirst, he ran too, but with a storm of other feelings. Outstripping all of them, very close at the heels of the dogs, kicking some, striking others with the hockey-stick, while the tears poured down his cheeks, he cried at the top of his voice to the hare leaping in front, “Run, mammy, run! clink (dodge), mammy, clink! Aw, mammy, mammy, run faster, run for your life, run!”

The hare dodged aside, shot into a thicket, and escaped its pursuers just as Corlett, the farmer, who had heard the outcry, came racing up with a gun. Then Pete swept his coat-sleeve across his gleaming eyes and leapt off home. When he got there, he found his mother sitting on the bink by the door knitting quietly. He threw himself into her arms and stroked her cheek with his hand.

“Oh, mammy, bogh,” he cried, “how well you run! If you never run in your life you run then.”

“Is the boy mad?” said Bridget.

But Pete went on stroking her cheek and crying between sobs of joy, “I heard Corlett shouting to the house for a gun and a fourpenny bit, and I thought I was never going to see mammy no more. But you did clink, mammy! You did, though!”

The next time Katherine Cregeen saw Peter Quilliam, he was sitting on the ridge of rock at the mouth of Ballure Glen, playing doleful strains on a home-made whistle, and looking the picture of desolation and despair. His mother was lying near to death. He had left Mrs. Cregeen, Kath-erine's mother, a good soul getting the name of Grannie, to watch and tend her while he came out to comfort his simple heart in this lone spot between the land and the sea.

Katherine's eyes filled at sight of him, and when, without looking up or speaking, he went on to play his crazy tunes, something took the girl by the throat and she broke down utterly.

“Never mind, Pete. No—I don't mean that—but don't cry, Pete.”

Pete was not crying at all, but only playing away on his whistle and gazing out to sea with a look of dumb vacancy. Katherine knelt beside him, put her arms around his neck, and cried for both of them.

Somebody hailed him from the hedge by the water-trough, and he rose, took off his cap, smoothed his hair with his hand, and walked towards the house without a word.

Bridget was dying of pleurisy, brought on by a long day's work at hoeing turnips in a soaking rain. Dr. Mylechreest had poulticed her lungs with mustard and linseed, but all to no purpose. “It's feeling the same as the sun on your back at harvest,” she murmured, yet the poultices brought no heat to her frozen chest.

Cæsar Cregeen was at her side; John the Clerk, too, called John the Widow; Kelly, the rural postman, who went by the name of Kelly the Thief; as well as Black Tom, her father. Cæsar was discoursing of sinners and their latter end. John was remembering how at his election to the clerkship he had rashly promised to bury the poor for nothing; Kelly was thinking he would be the first to carry the news to Christian Balla-whaine; and Black Tom was varying the exercise of pounding rock-sugar for his bees with that of breaking his playful wit on the dying woman.

“No use; I'm laving you; I'm going on my long journey,” said Bridget, while Granny used a shovel as a fan to relieve her gusty breathing.

“Got anything in your pocket for the road, woman?” said the thatcher.

“It's not houses of bricks and mortal I'm for calling at now,” she answered.

“Dear heart! Put up a bit of a prayer,” whispered Grannie to her husband; and Cæsar took a pinch of snuff out of his waistcoat pocket, and fell to “wrastling with the Lord.”

Bridget seemed to be comforted. “I see the jasper gates,” she panted, fixing her hazy eyes on the scraas under the thatch, from which broken spiders' webs hung down like rats' tails.

Then she called for Pete. She had something to give him. It was the stocking foot with the eighty greasy Manx banknotes which his father, Peter Christian, had paid her fifteen years before. Pete lit the candle and steadied it while Grannie cut the stocking from the wall side of the bed-ticking.

Black Tom dropped the sugar-pounder and exposed his broken teeth in his surprise at so much wealth; John the Widow blinked; and Kelly the Thief poked his head forward until the peak of his postman's cap fell on to the bridge of his nose.

A sea-fog lay over the land that morning, and when it lifted Bridget's soul went up as well.

“Poor thing! Poor thing!” said Grannie. “The ways were cold for her—cold, cold!”

“A dacent lass,” said John the Clerk; “and oughtn't to be buried with the common trash, seeing she's left money.”

“A hard-working woman, too, and on her feet for ever; but 'lowanced in her intellecks, for all,” said Kelly.

And Cæsar cried, “A brand plucked from the burning! Lord, give me more of the like at the judgment.”

When all was over, and tears both hot and cold were wiped away—Pete shed none of them—the neighbours who had stood with the lad in the churchyard on Maughold Head returned to the cottage by the water-trough to decide what was to be done with his eighty good bank-notes. “It's a fortune,” said one. “Let him put it with Mr. Dumbell,” said another. “Get the boy a trade first—he's a big lump now, sixteen for spring,” said a third. “A draper, eh?” said a fourth. “May I presume? My nephew, Bobbie Clucas, of Ramsey, now?” “A dacent man, very,” said John the Widow; “but if I'm not ambitious, there's my son-in-law, John Cowley. The lad's cut to a dot for a grocer, and what more nicer than having your own shop and your own name over the door, if you plaze—' Peter Quilliam, tay and sugar merchant!'—they're telling me John will be riding in his carriage and pair soon.”

“Chut! your grannie and your carriage and pairs,” shouted a rasping voice at last. It was Black Tom. “Who says the fortune is belonging to the lad at all? It's mine, and if there's law in the land I'll have it.”

Meanwhile, Pete, with the dull thud in his ears of earth falling on a coffin, had made his way down to Ballawhaine. He had never been there before, and he felt confused, but he did not tremble. Half-way up the carriage-drive he passed a sandy-haired youth of his own age, a slim dandy who hummed a tune and looked at him carelessly over his shoulder. Pete knew him—he was Boss, the boys called him Dross, son and heir of Christian Ballawhaine.

At the big house Pete asked for the master. The English footman, in scarlet knee-breeches, left him to wait in the stone hall. The place was very quiet and rather cold, but all as clean as a gull's wing. There was a dark table in the middle and a high-backed chair against the wall. Two oil pictures faced each other from opposite sides. One was of an old man without a beard, but with a high forehead, framed around with short grey hair. The other was of a woman with a tired look and a baby on her lap. Under this there was a little black picture that seemed to Pete to be the likeness of a fancy tombstone. And the print on it, so far as Pete could spell it out, was that of a tombstone too, “In loving memory of Verbena, beloved wife of Peter Chr—”

The Ballawhaine came crunching the sand on the hall-floor. He looked old, and had now a pent-house of bristly eyebrows of a different colour from his hair. Pete had often seen him on the road riding by.

“Well, my lad, what can I do for you?” he said. He spoke in a jerky voice, as if he thought to overawe the boy.

Pete fumbled his stocking cap. “Mothers dead,” he answered vacantly.

The Ballawhaine knew that already. Kelly the Thief had run hot-foot to inform him. He thought Pete had come to claim maintenance now that his mother was gone.

“So she's been telling you the same old story?” he said briskly.

At that Pete's face stiffened all at once. “She's been telling me that you're my father, sir.”

The Ballawhaine tried to laugh. “Indeed!” he replied; “it's a wise child, now, that knows its own father.”

“I'm not rightly knowing what you mane, sir,” said Pete.

Then the Ballawhaine fell to slandering the poor woman in her grave, declaring that she could not know who was the father of her child, and protesting that no son of hers should ever see the colour of money of his. Saying this with a snarl, he brought down his right hand with a thump on to the table. There was a big hairy mole near the joint of the first finger.

“Aisy, sir, if you plaze,” said Pete; “she was telling me you gave her this.”

He turned up the corner of his jersey, tugged out of his pocket, from behind his flaps, the eighty Manx bank-notes, and held them in his right hand on the table. There was a mole at the joint of Pete's first finger also.

The Ballawhaine saw it. He drew back his hand and slid it behind him. Then in another voice he said, “Well, my lad, isn't it enough? What are you wanting with more?”

“I'm not wanting more,” said Pete; “I'm not wanting this. Take it back,” and he put down the roll of notes between them.

The Ballawhaine sank into the chair, took a handkerchief out of his tails with the hand that had been lurking there, and began to mop his forehead. “Eh? How? What d'ye mean, boy?” he stammered.

“I mane,” said Pete, “that if I kept that money there is people would say my mother was a bad woman, and you bought her and paid her—I'm hearing the like at some of them.”

He took a step nearer. “And I mane, too, that you did wrong by my mother long ago, and now that she's dead you're blackening her; and you're a bad heart, and a low tongue, and if I was only a man, and didn't know you were my father, I'd break every bone in your skin.”

Then Pete twisted about and shouted into the dark part of the hall, “Come along, there, my ould cockatoo! It's time to be putting me to the door.”

The English footman in the scarlet breeches had been peeping from under the stairs.

That was Pete's first and last interview with his father. Peter Christian Ballawhaine was a terror in the Keys by this time, but he had trembled before his son like a whipped cur.

V.

––––––––

KATHERINE CREGEEN, Pete's champion at school, had been his companion at home as well. She was two years younger than Pete. Her hair was a black as a gipsy's, and her face as brown as a berry. In summer she liked best to wear a red frock without sleeves, no boots and no stockings, no collar and no bonnet, not even a sun-bonnet. From constant exposure to the sun and rain her arms and legs were as ruddy as her cheeks, and covered with a soft silken down. So often did you see her teeth that you would have said she was always laughing. Her laugh was a little saucy trill given out with head aside and eyes aslant, like that of a squirrel when he is at a safe height above your head, and has a nut in his open jaws.