Eternal Living E-Book

22,15 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 21,20 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 21,20 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: IVP Formatio

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

Dallas Willard spent his life making eternal living concrete for his friends. With his unexpected passing in 2013, the world lost a brilliant mind. The wide breadth of his impact inspired friends, family, colleagues, students and leaders of the church to gather their reflections on this celebrated yet humble theologian and philosopher. Richard Foster, a friend for over forty years, writes of Dallas: "He possessed in his person a spiritual formation into Christlikeness that was simply astonishing to all who were around him. Profound character formation had transpired in his body and mind and spirit until love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control were at the very center of the deep habit-structures of his life. He exhibited a substantively transformed life. Dallas was simply soaked in the presence of the living Christ."Curated by Gary Moon, director of the Dallas Willard Center, this medley of Dallas's wise teaching and lived model of Christlikeness—as well as snapshots and "Dallas-isms"—will move and motivate readers. Whether influenced by him as a family member, close friend, advisor, professor, philosopher, minister or reformer, contributors bring refreshing insight into not only his ideas and what shaped him, but also to his contagious theology of grace and joy.Contributors include: - Richard J. Foster - Jane Willard - J. P. Moreland - John Ortberg - James Bryan Smith - Alan Fadling - Ruth Haley Barton - and dozens more

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Reflections on Dallas Willard’s Teaching on Faith & Formation

Eternal Living

Edited by Gary W. Moon

www.IVPress.com/books

InterVarsity Press

P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL [email protected]

©2015 by Gary W. Moon

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

InterVarsity Press® is the book-publishing division of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA®, a movement of students and faculty active on campus at hundreds of universities, colleges and schools of nursing in the United States of America, and a member movement of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. For information about local and regional activities, write Public Relations Dept., InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA, 6400 Schroeder Rd., P.O. Box 7895, Madison, WI 53707-7895, or visit the IVCF website at www.intervarsity.org.

While all stories in this book are true, some names and identifying information in this book have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

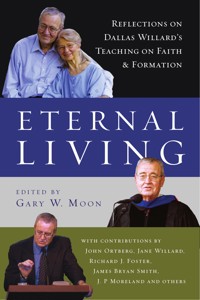

Cover design: Cindy Kiple Images: Dallas Willard and his wife: Dieter Zander Dallas Willard: Courtesy of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA

This book is dedicated to

Dallas Albert Willard— there were indeed giants in the land.

Bertha Von Allman Willard— she lovingly stepped into the shoes of Maymie Willard after her premature death and later said of Dallas, “We were so young, we had to raise each other.”

To Dallas Willard’s family, friends, colleagues and students, the thirty who contributed to this book and the thousands more who could have.

Contents

Preface

Introduction: Living in the Glow of God

Part I Husband, Father and Friend

1 If Death My Friend and Me Divide

2 Family Voices

3 A Word from a Different Reality

4 The Beauty of a Virtuous Man

5 The Evidential Force of Dallas Willard

Part II Philosopher and Professor

6 Moving Beyond the Corner of the Checkerboard

7 From Secular Philosophy to Faith

8 Reflections on a Day with My Professor and Friend

9 Five Tips for a Teacher

10 Widening Spheres of Influence

Part III Mentor and Reformer of the Church

11 Master of Metanoia, Bermuda Shorts and Wingtips

12 Journey into Joy

13 Dallas Willard, Evangelist

14 Developing Pastors and Churches of the Kingdom

15 Gray’s Anatomy and the Soul

16 The Kingdom of God Is Real

17 A Few Dallas-isms That Changed My Life

18 The Real Deal

19 Equally at Home in Private and Public Spheres

20 Conclusion: Hey Dallas . . .

Notes

About the Author

Renovaré

Dallas Willard Center

Formatio

More Titles from InterVarsity Press

“Lead, Kindly Light”

by John Henry Newman, 1833

Lead, kindly Light, amid th’ encircling gloom, lead Thou me on!

The night is dark, and I am far from home; lead Thou me on!

Keep Thou my feet; I do not ask to see

The distant scene; one step enough for me.

I was not ever thus, nor prayed that Thou shouldst lead me on;

I loved to choose and see my path; but now lead Thou me on!

I loved the garish day, and, spite of fears,

Pride ruled my will. Remember not past years!

So long Thy power hath blest me, sure it still will lead me on.

O’er moor and fen, o’er crag and torrent, till the night is gone,

And with the morn those angel faces smile, which I

Have loved long since, and lost awhile!

Preface

Gary W. Moon

On May 4, 2013, in the earliest glow before dawn, amid the smells of disinfectant and death, the great kingdom communicator turned his face away from the friend in his room and said his last two words, apparently to the Author of his life: “Thank you.”1

It is fitting that the last earthly words of Dallas Albert Willard would be eucharistic. He gave thanks, eucharisteō, echoing the words of his friend Jesus spoken before he broke a loaf of bread that made eternal living concrete for his friends. Dallas Willard spent his life making eternal living concrete for his friends. So it also seems beautifully fitting that embedded within the word Eucharist we find the two words that defined Dallas Willard’s contagious theology: grace and joy.

Even with his last breath, it seems, he was still teaching out of lived experiences.

It is also appropriate that in the months that followed there would be not one or two but three memorial services for Dallas Willard. The kaleidoscope of memories and the diversity of the lives he had touched could not be confined to one gathering. As Aaron Preston summarized, there was a “unique grandeur” to the thinking and teaching of this man.2

The horizons of his knowledge were, indeed, vast and expansive. His friend and colleague Scott Soames described Dallas as “the teacher with the greatest range in the School of Philosophy at the University of Southern California.”3 But philosophy was not his only area of broad expertise. The man who chose podium over pulpit was given back both and became one of the most influential reformers of the Christian church of his generation.4 He was also avidly read by expanding numbers of spiritual directors, Christian psychologists and a host of people in the pews who hunger for a theology that makes sense and for experiences of God that are not of this world.

It has been observed that Dallas Willard did not set out to “make a movement or foster a trend. He did intend to cast a big vision for a ‘big God’ in a big world.”5 Part of this “bigness” is seen in Dallas’s approach to disciplines such as philosophy and biblical theology, in which, while being respectful, he was not confined by the current norms. “Instead, he focused on broad, fundamental, and enduring issues, approaching them in a way that was rigorous but non-technical and always historically informed.”6

The breadth of Dallas Willard’s interests may best be captured by the fact that much of his writing and thought during his last decade of life rose even further above ongoing academic and ecclesiastical debates and focused on his vision for reforming the academy itself. His desire was to reclaim moral knowledge and cast a grand idea for a society where its shapers—those in the public square of business, government, entertainment, education—would practice their professions as residents of the kingdom, enrolled in “schools of life” taught by pastors and lived by all.

Given all this it was no surprise that the broad scope of Dallas Willard’s interests was also reflected in the variety of individuals who attended one or more of his three memorial services. One service (May 8, 2013) was primarily for those who knew Dallas as a family member, long-time friend or adviser. The focus of another (October 4, 2013) was on those who knew Dallas best as a philosopher and colleague during his forty-seven years at USC. Between these, one tribute (May 25, 2013) gave more attention to those who knew him as a minister and reformer of the church.

The vision for creating this book is driven by Dallas Willard’s influence on such a diversity of individuals. We have used the themes of the three memorials for Dallas as a way of organizing these reflections. It is not our intent to glorify or call undue attention to Dallas. Those who knew him know that he would hate that. The intent is to provide a medley of images, stories and “Dallas-isms” from many individuals who were deeply influenced by him as a family member, close friend, adviser, professor, philosopher, minister or reformer. For some who are writing, each of these labels and more may apply. The intent is for the reader to be moved and motivated toward deeper experiences of God through the sharing of stories about Dallas’s influence on the lives of the writers.

Contributors have been asked to do three things. After describing special “snapshots” of time spent with Dallas, each friend explains how their shared life with Dallas has impacted their personal and professional life, and finally reflects on how these insights may be generalized to the readers of this book. Dallas Albert Willard lived a very big life. We do not present here his point of view, but a variety of points from which Dallas was viewed. We present what at times may seem like an intimate home movie—the rare kind that you actually enjoy viewing.

It should be observed that while you will be hearing from thirty voices, this chorus could have rightly included many more. Each of the thirty-one students whose dissertations Dallas chaired and the thousands of others who were students and colleagues at USC could share so much more—as could the seven hundred students who took his two-week intensive class at Fuller, the two hundred Renovaré Institute students who devoted two years to studying his influence on Christian spiritual formation, and scores of others who knew him only through his dense and hope-filled words that became windows into the here-and-now kingdom of God.

INTRODUCTION

Living in the Glow of God

Gary W. Moon

God seems to place great value on humble beginnings. His son descended into a manger, chose rabbi school dropouts to be his students and compared the kingdom to a tiny mustard seed. There seems to be a pattern: In weakness there can be strength; in poverty, great riches.

The life of Dallas Albert Willard fits this mold. He was born on September 4, 1935, in Buffalo, Missouri, in the midst of the Great Depression. He lived his first eighteen months in a small, rented house. The small town of Buffalo was founded in 1839 as a pioneer village on the edge of the prairie and the Niangua River hills and woodlands. It was an isolated settlement that promised a fresh start for western pioneers in search of a new way to live.

Dallas was named for the county of his birth, Dallas, Missouri, which was originally organized under the name Niangua in 1841. The word Niangua is from an old Native American phrase meaning “I won’t go away,”1 which proved to be a poignant if not bittersweet promise to the young Dallas Willard. During the early years of his life, it seemed that people he loved very often went away.

Keep Eternity Before the Eyes of the Children

Dallas was born to Albert Alexander and Maymie Lindesmith. “Lindesmith is a German name,” Dallas pointed out. “She was from Switzerland.”2 His amazing mind, unfortunately, contained no visual memories of his mother. She died in February of 1938 when he was only two and a half years old.

Maymie had jumped from a hay wagon and the impact caused a hernia. The needed surgery required a trip across the state line to a larger town, Topeka, Kansas. Dallas stayed with his maternal grandmother, Myrtle Pease, along with his three older siblings, J. I., Fran and Dwayne—who at the time were sixteen, nine and six years of age. While away, Maymie developed a fever and the surgery had to be put off for a few days. From her hospital bed she wrote poems to her children as a substitute for her loving presence.

The surgery was eventually performed, but poorly. Maymie got worse and never returned home. The last thing she said to her husband, just before she died, was, “Keep eternity before the eyes of the children.”

The funeral director confirmed the family’s fear that the surgeon had done a bad job. Two-year-old Dallas didn’t understand what was happening, and during the funeral or wake he tried to climb into the casket to be with his mother.

Dallas was left to be raised by his father, whom he described as a “nondescript farmer, who later dabbled in local politics.”3 Dallas remembered that following the death of his mother, his father became a “crushed man,” feeling somehow responsible for her death.

Early Education

Much of Dallas’s early education was in one-room school buildings. While the dimensions of the classroom setting stayed fairly consistent, not much else did during Dallas’s early years. Over the course of his time in elementary and high school he lived in multiple towns in three different counties—Dallas, Howell and Oregon. At one time or another he lived with his father and paternal grandparents; his father and stepmother, Myrtle Green; his paternal grandparents; and his older brother J. I. and his wife, Bertha. He was with J. I. and Bertha during his second- and eighth-grade years. Bertha was very young, eighteen, when five-year-old Dallas first lived with them. She once said, “I didn’t raise Dallas: Dallas and I raised each other.”

With all the moves and instability of these early years there were some constants: a love for learning, a love for God and the recognition of Dallas’s natural gifts.

“In preschool I learned to love words; it was almost magical. I remember having appreciation for my first-grade teacher; I don’t remember her name. But that first year, I discovered you could learn things, and that had been a great mystery. The discovery of learning was really huge. It opened up things. It said there are all these things and places you don’t know, but you can go into them in your mind.”

As might be expected, he spent much of his youth reading. He would latch on to one author and read novel after novel. Jack London was a particular favorite. “The Sea-Wolf was a big book for me. It is basically philosophical stuff, life work.”

Dallas was baptized when he was nine years old. The pastor “was a gentle man that presented Christ in a very loving way. I had decided to go forward [to make a commitment to Christ, but] because the pastor was not there I did not go that night. I really suffered for the next week; I felt burdened. I wanted to do this thing. So the next Sunday he was there and I went forward, and it was a remarkable experience. I remember how different the world looked as I walked home in the dark. The stars, the streetlights were so different and I still have the impression that the world was really different. I felt at home in this new world. It felt like this is a good place to be; Christ is real.”

Dallas was very popular in school and was elected class president his freshmen and senior years at Thomasville High School. He took that job quite seriously and was active in class reunions for decades to come. He played basketball all four years of high school and was “first string” his senior year. He also had a musical and theatrical side. Dallas graduated from Thomasville High School in 1951, as part of a graduating class of eleven people.

For most of his high school years, Dallas lived on a farm with lots of animals. He would shear sheep and help in the birthing of lambs, calves and colts. “It is hard not to love lambs,” he said, “especially while watching them bounce down a hill on all fours.”

Migrant Worker

After graduation Dallas spent the next year and a half working as a migrant agricultural worker by day and a self-taught student by night—reading Plato and Kipling after the sun had gone down. Most of this time was spent in Oklahoma and Nebraska, but he also worked for a while in Idaho. During that time away from home Dallas also became a roofer.

Then Dallas came back to Missouri for a while and spent time with his brother J. I., who was running a large dairy farm in Liberty, near Kansas City. “He told me I had to go to college and recommended William Jewell—which was nearby—and physically took me there. After I spent some time at William Jewell, he said I had to go to Tennessee Temple. I think he knew about Tennessee Temple because he had been a reader of the periodical Sword of the Lord.”

Spiritual Awakening

Beginning in the fall of 1954 Dallas spent thirty months of his life in the beautiful river town of Chattanooga, Tennessee, attending Tennessee Temple College. Some might consider this an unusual starting point for someone who would later serve as director of the philosophy department at a major secular university. And at that time, the college was an unaccredited Bible school that served independent Baptist congregations—and churches that were even more conservative. But it was at this institution that Dallas had many experiences that would change the course of his life and career.

Most important, Dallas Willard met Jane Lakes of Macon, Georgia, in the library at Tennessee Temple. In Dallas’s words: “Jane was this beautiful young woman. She was a student who worked in the library. She appeared so far beyond me that for a while I couldn’t get the nerve to talk to her.” But eventually he did.

One of the first things Jane noticed about Dallas was that he was not wearing socks. She thought he must have had a rebellious streak, a budding James Dean perhaps. She later found out he was just too poor to buy socks. They both agreed that Dallas began to frequent the library quite a lot.

It wasn’t long before Dallas and Jane were participating in student-led evangelistic activities. “She would play the organ and I would sing and preach. And we would also go to surrounding, mostly black, neighborhoods with the ‘good news’ club. We also went to local jails and held street meetings.” Dallas was listening to a radio preacher named J. Harold Smith at the time and Jane believes Dallas patterned his preaching after Smith early in his ministry.

Jane was a little older and two years ahead of Dallas in school. This helped motivate him to finish his degree in two and a half years. Jane graduated a year before Dallas, and they married before he graduated.

Academically, Dallas decided to major in psychology, in large part due to his appreciation for a professor named John Herman. “Dr. Herman was supposedly a psychologist, but he was [certainly] a teacher par excellence. He was very smart and enthusiastic. He was like Tony Campolo. High energy. He also brought a marvelous supplementation to the dead, dry Baptist orthodoxy. He was the main reason I majored in psychology.”

One evening, following a special service on campus, Dallas had an unexpected encounter with God. The last thing he remembered was R. R. Brown’s hand coming toward him. What followed was a vivid experience with the presence of God. “It stayed with me for days, weeks. It never left me really,” Dallas said. “After that I never had the feeling that God was distant or had a problem hearing me.” That night when they went to bed, Jane related, Dallas exclaimed, “There is an angel at each corner of the bed.” Dallas added, “I did not have an image but a sense that they were there.”

During those years Dallas stumbled across a copy of The Imitation of Christ—“I still have that book.” He also was given a copy of Deeper Experiences of Famous Christians. “My friend Dudley gave me the copy. It is not a good book [from a literary perspective], but it gave me a broader view of what it meant to be a follower of Christ. It blew me out of Baptist-ism. It wasn’t long until I would wear a bolo tie and a see-through shirt with the tail out, and no socks with shoes. It was getting over legalism.”

Academic Awakening

In the fall of 1956, after graduating from Tennessee Temple, Dallas and Jane moved from Chattanooga back (for Dallas) to Thomasville, Missouri. They both taught for a few months (from September to January) in the high school Dallas had attended.

On February 16, 1957, Jane gave birth to their son, John Willard. Following John’s birth, they moved from Thomasville to Waco, Texas. The move was very difficult as they were pulling the house trailer in which they would live. Along the way they endured eight flat tires, and they arrived at Baylor University with thirty-five cents in Dallas’s pocket—a quarter and a dime—and a two-week-old baby in Jane’s arms.

Not long after beginning studies at Baylor University—for the purpose of obtaining a second (and accredited) undergraduate degree—Dallas discovered an entirely new area of his brain: the scholarly, intellectual side. He had not thought much about a career path, by default assuming he would be a minister. But at Baylor, he recalled, “My awareness of what the life of intelligence was about deepened. I was raised so that you didn’t think about things like philosophy. You figured you were just lucky to stay alive.” The more Dallas thought, the more thoughtful he became. While he never lost his deep love for Scripture—that would forever keep him grounded—a new dimension was being added.

Dallas completed an undergraduate degree in religion at Baylor, but most of the coursework was in philosophy. During those two and a half years in Waco he also completed all the units necessary for a master’s in psychology, but did not claim the degree. It didn’t matter. The degree was secondary to something much more important. It was while he was in the graduate program that he began to hear discussions about the kingdom of God.

After Dallas completed his work at Baylor, he moved with Jane and John to Warner Robbins, Georgia, near Jane’s hometown of Macon. Jane taught junior high school and Dallas taught high school in Warner Robbins. Dallas also served as associate pastor at Avandel Baptist Church in Macon, where Jane had attended as a child.

It was during that year, Dallas reported, that he became convicted about how little he knew about God and the soul. “I was totally incapable of making any sense of God and the human soul and decided during that winter to go back to graduate school in philosophy for a couple of years just to improve my understanding. I had no intent to take a degree.”

“At the end of that summer of 1959, we loaded up a U-Haul and drove up Highway 41 all the way from Macon to downtown Chicago and then on to Madison. Little John was in the back seat; he was two years old.”

Dallas began studies at the University of Wisconsin in the fall of 1959 and completed a PhD in 1964. The degree “included a major in philosophy and a minor in the history of science.” He also picked up a second degree in fatherhood. Becky Willard was born on February 17, 1962, at the University Hospital, where Jane was also an employee.

During Dallas’s time at the University of Wisconsin, three things happened that would change his life and, perhaps, the face of evangelicalism.

First, Dallas met and became friends with a number of individuals who helped him gain a vision for the importance of the academy to the kingdom and for the university as a place of evangelism. Stan Matson, part of the InterVarsity group on campus; John Alexander, who later became head of InterVarsity worldwide; David Noble, who would go on to start Summit Ministries; and Harold Myra, who later became president of Christianity Today, were all important to Dallas. However, it was Earl Aldridge, a professor in the Spanish department, who echoed words Dallas says he had already heard spoken by God into his fertile mind: “If you go to the church you will have the church, but if you go to the university the churches will also be given.”

The second game-changing discovery was the subject of Dallas’s dissertation: Edmund Husserl, the father of phenomenology.4 While we will devote an entire chapter of this volume to the importance of Husserl to Dallas Willard’s thinking, it is important to hear about this connection in Dallas’s own words.

“Husserl offered an explanation of consciousness in all its forms that elucidates why realism is possible. He helped me to understand that in religion you also have knowledge and you are dealing with reality. What Jesus taught was a source of knowledge, real knowledge, and not merely an invitation to a leap of faith. . . . Husserl does not allow you to get in a position to say all you have is a story. You live in a world that is real, and this applies to morality as well as to physics. . . . Science took over the university and [in the process] we lost values and morality, and that is the crisis. And postmodernism is a reaction to the idea that science is the only way.”

After hearing Dallas explain this I asked him, “Is this why your theology seems to me to be more at home in the church of the first few centuries than with modern evangelicalism?” His quick response: “Absolutely! The early church did not get stuck in a Cartesian box. Aristotle thought there were a real world and a real mind that could know it. And that is what disappears. I have watched scientists listen to postmodernists and it is a constant display of thinly veiled disgust.”

Husserl helped Dallas defend the notion that Jesus was describing a knowable reality when he talked about the kingdom and the Trinity. But there was an additional result from Dallas’s time in Madison. He began to believe in his ability to “do philosophy” in a high-level academic setting.

The third thing was acceptance by the academic community. Dallas described what happened after he presented a paper: “The paper I presented was a turning point because I wrote that and read it to a philosophy group and they were impressed. After that my peers and the faculty treated me differently.” Dallas’s eyes may have reflected just a hint of pride. “It called my attention to, ‘Okay, Willard, you can do this type of philosophy,’ and that was very important to the future. It went along with passing the final exams. Most of that paper was incorporated into my dissertation (first chapter) and the basic point has been substantial to everything I’ve done: you don’t get a special clarity by talking about language.”

Dallas completed his PhD at the University of Wisconsin in 1964 and taught there for one year. In the fall of 1965, when Dallas was thirty years old, he and Jane, John and Becky moved from Madison, Wisconsin, to Los Angeles, California, where he had accepted a position in the philosophy department at the University of Southern California. They traveled along historic Route 66 for much of the trip.

We are now entering the time in Dallas’s life when, through his role as professor and mentor to ministers, he began to meet many individuals who have authored these chapters. I will provide just a few more highlights before tagging out to the other voices.

Professor and Minister to Ministers

Dallas Willard was greatly admired as a professor and contributor to student life at USC. In 1976 he won the Blue Key National Honor Fraternity “Outstanding Faculty Member” award for his contributions to student life. In 1977 he received the USC Associates Award for Excellence in Teaching. In 1984 he won the USC Student Senate Award for Outstanding Faculty of the Year, and in 2000 he was named the Gamma Sigma Delta Professor of the Year. Indeed, for three years (fall of 1981 through spring of 1984) the Willards lived with the students while participating in USC’s Faculty in Residence program.

From 1982 to 1985 Dallas served as the director of the School of Philosophy. But in his words, “I became department chair only because some leading members of the faculty came to me and said you must do this. I only did this so they would not ask me to do it again. I had it firmly in my mind that I did not come there to administer.”

While Dallas was pouring his life into the lives of students and faculty members at USC, he also began to have significant “accidental” mentoring relationships with ministers who would in time have a great impact on the church.5 One of these key relationships may never have happened except for Dallas and Jane’s decision to move out into the country.

After spending their first year on the West Coast in Mar Vista in West Hollywood, Dallas and Jane bought a house in Chatsworth, California, and lived there together for almost forty-six years—excluding the three years they lived on the USC campus. The house is small and sits on top of the ridge of a small mountain. The terrain is very rocky and the surrounding area so remote that it was used for the making of many Western films and television series. It could be argued that if the rock population were diminished a bit and the ground more flat, Dallas had found the closest thing to rural Missouri that existed within an hour’s drive of the USC campus. When four-year-old Becky Willard found a frog in a gopher hole, the real estate deal was done.

Not long after moving to Chatsworth, the Willards began attending a small Friends church on Woodlake Avenue in the fall of 1966. “We went because of the pastor, Jim Hewitt. He preached good sermons, had a master’s in English literature and was a Fuller graduate. Jim became really involved in our lives. He left to become a Presbyterian.”

In the fall of 1969 the Friends denomination sent a young, fresh out of seminary student to pastor the Woodlake Avenue Church. His name was Richard J. Foster. Dallas said, “I thought, Now here is a lovely, smart young man. He is a winning man. And basically we started talking and never stopped.”

I’ll leave it to Richard himself to tell the rest of that story (see chapter two). But to say the least, the two men formed a beautiful friendship, which eventually led to the creation of the ministry Renovaré and ignited a movement that some would argue has become one of the most significant happenings in the church during the past century.

Richard J. Foster represents a multitude in the church world who were drawn to the ideas of the professional philosopher, amateur theologian and practical mystic Dallas Willard. And I think each would say that more inviting than his fresh ideas was the fact that Dallas lived what he believed. As John Ortberg put it, “he lived in another time zone.”6

The Really Big Ideas

There have been several attempts to capture Dallas Willard’s big ideas. In 2007 the Renovaré Institute was established to provide a two-year study experience that allows students to systematically soak in the twelve critical concepts of Renovaré—the majority of which can be traced directly or indirectly to the thinking of Dallas Willard.7 The most concise presentation of Dallas’s vision for Christian spiritual formation and churches becoming “schools of life” is found in his own words, in brief summaries of his primary Christian writings. He described his books this way:

In the first, In Search of Guidance, I attempted to make real and clear the intimate quality of life with [Jesus] as “a conversational relationship with God.”

But that relationship is not something that automatically happens, and we do not receive it by passive infusion. So the second book, The Spirit of the Disciplines, explains how disciples or students of Jesus can effectively interact with the grace and spirit of God to access fully the provisions and character intended for us in the gift of eternal life.

However, actual discipleship or apprenticeship to Jesus is, in our day, no longer thought of as in any way essential to faith in him. . . . The third book, then, presents discipleship to Jesus as the very heart of the gospel. The really good news for humanity is that Jesus is now taking students in the master class of life. The eternal life that begins with confidence in Jesus is a life in his present kingdom, now on earth and available to all.8

It could be argued that the key purpose for Renovation of the Heart was to provide understanding concerning how to bring the various dimensions of the human self under God’s reign, and Knowing Christ Today sought to underscore that knowledge of the reality of Christ is available through interactive experience of the Trinity.

I believe that if one were asked to identify a single golden thread that runs through each of Dallas Willard’s books—a key idea that sets his thinking apart from so many others—it would be the idea that it is actually possible to step into the words of John 17:3 and enter into an experiential relationship, a transforming friendship, with the Trinity. In the words of Steve Porter, an ordinary person can grab hold of life from above.9 An ordinary person can live a “with-God” life—surrendered and obedient to divine will.

Pain, Presence, Light, Knowledge and Scripture

Sometimes in intimate conversation, Dallas’s face would show lines of regret and his eyes would drop when he confessed wishing he had been a better husband and father. But it was in that pain that he found a powerful God—residing at, as he might say, “the-end-of-my-rope.com.” Dallas did not start breathing the Lord’s Prayer and twenty-third Psalm before getting out of bed for the purpose of keeping a devotional score card. Instead, he had entered a time of suffering so intense that he did not want to put his feet on the floor before being reassured that his Father’s kingdom is a good and perfectly safe place.

Dallas shared the memory that as a boy he would try to cut wood for neighbors just right, a perfect fit for the fireplace or wood stove, because, he reasoned, if you please people you may be asked to stay for a while. It may well be that the pain caused by the sudden absence of a loved one created a deep desire for presence in Dallas’s life that eventually led him to the greatest discovery and most important theme of his writing: We can live our lives in a constant and transforming friendship with a loving God, who will never go away, and who is not that picky about how wood is cut.

In addition to Dallas’s belief in the here, now and forever presence and experiential reality of God, he also seemed fascinated by the light, energy and glow of God. It could be said that he was an unlikely and ultra-practical mystic. But understand, by using the term mystic I simply mean that he believed God is present in a real sense and that when you talk with him a two-way conversation is possible. And for Dallas, the light and life of God was very real and present.

Two of the churches he attended for long periods of time were a Quaker and a Vineyard congregation. It could be argued that geography and Jane’s appreciation for the Vineyard were the key factors for those church choices. But Dallas was particularly drawn to the life and ministry of John Wimber, and was deeply appreciative of the healing ministries of Bill Vaswig and Agnes Sanford and her book The Healing Light. Environments where the experience of God could be celebrated and expected seemed to have a magnetic attraction for Dallas.

While Dallas Willard may have been a practical mystic, a person for whom the presence and light of God were as real as the flow of electricity into a light bulb, there were two factors that contributed mightily to the profoundness of his thinking and writing about these themes. The first is his connection to Edmund Husserl; the second is his connection to Scripture.

Dallas believed people will indeed perish for lack of knowledge, but may find eternal living through knowledge of the Trinity. In fact, because of the impact of Husserl on his thinking, Dallas actually believed that while much of the modern world and most in the academy have lost knowledge as the center of what matters most, knowledge of God is not only possible but also ultimately as measurable as events in a physics laboratory. His evangelistic efforts were not to produce a leap of faith but interactive knowledge of God.

Pain. Presence. Light. Knowledge. And Scripture. Dallas Willard’s life experiences provided this Southern Baptist minister, professional philosopher, amateur theologian and practical mystic with an appreciation for and approach to Scripture that was most unusual. He was able to simultaneously maintain a high view and deep love of the Bible—as evidenced by the wear on the cover and the notes scribbled in most every margin—while being able to view it in a way that was outside most Christian boxes.

He was able to approach Scripture with the reverence of a Southern Baptist, the mind of a respected philosopher and the vision of a mystic. The result appears to be a theology and view of God that is much more at home in the early church than with modern evangelicalism. And that’s the whole deal. Dallas Willard was a reformer of the modern evangelical church, pointing back to its early roots and across the centuries to times when lives were being transformed through participation in the here, now and real life with the Trinity.

Meeting Dallas

My first encounter with Dallas Willard was in the late fall of 1989 and was very dramatic—even though he was more than 2,400 miles away. It was one of those few moments in life that becomes seared into memory and never forgotten. I still remember the pattern of color on the sofa where I lay reading, the rough texture of the blue book in my hand, my musing whether I’d save ink by underlining what was unimportant, and the picture on the wall that my eyes landed on after I looked up from the words on the page and thought, “This is what I’ve been waiting to read my entire life.” Dallas’s words gave me hope that the gap between the high-sounding promises of Jesus and the low-lying practices of my Christian walk could be closed.

The book was The Spirit of the Disciplines. It was recommended to me by a friend as a must-read. I followed his advice because I enjoyed reading Celebration of Discipline nine years earlier as part of a class Richard J. Foster was teaching at Fuller Seminary in 1980.

Within a few months I asked both Dallas Willard and Richard Foster to be part of an advisory board for something I was putting together called The Institute of Clinical Theology. To my great surprise each said yes, and each later agreed to be a speaker at two separate conferences to be held by the institute.

Dallas spoke at the first of the conferences. It was held in Virginia Beach in the spring of 1992. Before the event Dallas sat in our small house—I did not realize he would have considered it a big house—eating coconut cake on the sofa where I had first been exposed to his thinking. He was fifty-six years old.

We drove to the event and he started the conference with a line that warmed my heart: “All theology should be clinical theology.” The only fan letter I ever wrote I put in his hands as he was leaving for the airport.